Abstract

Migration of TH cells to peripheral sites of inflammation is essential for execution of their effector function. The recently described TH9 subset characteristically produces IL-9 and has been implicated in both allergy and autoimmunity. Despite this, the migratory properties of TH9 cells remain enigmatic. In this study, we have examined chemokine receptor usage by TH9 cells and demonstrate, in models of allergy and autoimmunity, that these cells express functional CCR3, CCR6 and CXCR3, chemokine receptors commonly associated with other, functionally opposed, effector TH subsets. Most TH9 cells that express CCR3 also express CXCR3 and CCR6 and expression of these receptors appears to account for the recruitment of TH9 cells to disparate inflammatory sites. During allergic inflammation, TH9 cells utilize CCR3 and CCR6 but not CXCR3 to home to the peritoneal cavity, whereas TH9 homing to the central nervous system (CNS) during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) involves CXCR3 and CCR6 but not CCR3. These data provide the first insights into regulation of TH9 cell trafficking in allergy and autoimmunity.

INTRODUCTION

TH9 cells are the most recently described TH cell subset but their in vivo function is incompletely understood and their homing capacity remains unknown. TH9 differentiation is dependent on TGF-β and IL-4 and these cells express the pleitropic cytokine IL-9, but no other TH-lineage-specific cytokine or transcription factor (1, 2). TH9 cells are described to be functionally dynamic with reports that they participate in mechanistically disparate forms of inflammation such as allergy and autoimmunity, once thought to be restricted to the functions of TH2 and TH1/TH17 cells, respectively (3).

The role of IL-9 in adaptive immunity has been most closely associated with type-2 inflammatory settings including anti-parasitic and allergic inflammation. Despite one study that reported normal development of allergic inflammation in Il9−/− mice using a sensitisation-challenge model of allergy (4), several studies have demonstrated a protective effect of IL-9 neutralisation/blockade, characterised by reduced lung eosinophillia, serum IgE and airways epithelial damage, using similar models (5–7). Following reports that T cells were major cellular sources of IL-9 (8); and detection of IL-9 production from T cells in Leishmania major-infected BALB/c mice, an infection model that elicits a strong TH2-driven inflammatory response (9), IL-9 was originally classified as a TH2-derived cytokine. However, owing to a lack of suitable monoclonal antibody to IL-9 at the time of these studies, reliable flow cytometric analyses of IL-4/IL-9 co-expression by TH2 cells on a single-cell level did not exist. More recently, two independent laboratories demonstrated that the presence of IL-4 and TGF-β during TCR-mediated activation drove differentiation of a CD4+ T-cell subset that lacked expression of T-bet, GATA-3, FoxP3 and RORγt, preferentially produced IL-9, but not IL-4, and was subsequently designated TH9 (1, 2). Since this discovery, other studies have now exemplified the importance of TH9-derived IL-9 in promoting allergic inflammation. In a T-cell transfer model of allergic airway disease, adoptive transfer of in vitro-generated TH9 or TH2 cells into Rag2-deficient recipients led to development of allergic pulmonary inflammation characterised by increased airway reactivity to methacholine and augmented eosinophil recruitment following airways challenge (10). Co-administration of IL-9 neutralisation antibody profoundly ameliorated TH9 cell-induced asthma, but had little effect in mice that received TH2 cells (10). Furthermore, a role for TH9 cells in promoting allergic inflammation is supported by a recent study demonstrating a requirement for T-cell expression of the TH9-promoting transcription factor PU.1 in experimental asthma (11). Mice with a T cell-specific deletion of PU.1 failed to generate TH9 cells and were resistant to IL-9-dependent allergic inflammation, despite the generation of a normal TH2 response, clearly establishing PU.1 as a master regulator of TH9 development and TH9 cells as important mediators of allergy (11). Collectively, these studies demonstrate that TH9 cells, in concert with TH2 cells, drive the pathogenesis of type-2 inflammatory disease.

Numerous studies have also demonstrated the pro-inflammatory nature of TH9 cells in autoimmune inflammatory settings. In a T-cell transfer model of colitis, adoptive transfer of in vitro-generated TH9 cells into Rag1-deficient recipient mice led to significant weight loss associated with induction of colitis and peripheral neuritis (2). Moreover, co-transfer of TH9 cells with CD45RBhiCD4+ effector T-cells resulted in heightened pathology relative to mice that received transfer of CD45RBhiCD4+ effector T cells alone (2). The pathogenic effector functions of TH9 cells have been further explored more recently in the context of EAE. Adoptive transfer of in vitro-generated enchepalitogenic TH9 cells into naïve hosts led to development of neuroinflammatory CNS lesions and induction of severe EAE (12). Consistent with the results of these studies, inhibition of IL-9, using IL-9-deficient mice or antibody-mediated neutralisation of IL-9 or its receptor, has been shown to ameliorate EAE (13–15), although, in most studies, the cellular source of IL-9 was not specifically addressed. Furthermore, adoptive transfer of hen egg lysozyme (HEL)-specific TH9 cells into recipient mice that express a HEL transgene in the eye led to induction of moderate ocular inflammation, exemplifying the proinflammatory nature of this subset in the context of autoimmunity (16). Collectively, these studies suggest that TH9 cells can contribute to the pathogenesis of autoimmunity in multiple organ systems.

Together, these observations raise an important question regarding TH9 biology: how do TH9 cells migrate to diverse sites of inflammation that normally differentially recruit TH1/TH17 and TH2 cells? It is known that stimuli encountered during T cell priming sets up a transcriptional programme in CD4+ T cells tailoring their function to combat the initiating stimulus whilst imprinting a lineage-specific and tissue-tropic chemokine receptor expression profile that facilitates migration to defined inflammatory sites (17). Chemokine receptor usage by naïve, TH1, TH2, TH17 and Treg cells is well documented (17, 18), whereas the migratory capacity of the functionally dynamic TH9 subset remains unknown. Therefore, in the present study, we examined chemokine receptor usage by TH9 cells and determined the homing receptors involved in their recruitment to sites of allergic and autoimmune inflammation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice, immunisation strategies and in vivo chemokine receptor antagonism

Eight to ten week old C57Bl/6, BALB/c and SJL/j mice were obtained from the University of Adelaide Animal House. To generate TH9 cells under allergic conditions, BALB/c mice were immunised subcutaneously in hind flanks with 100µg type IV ovalbumin (OVA) (Sigma) in 100µL aluminium hydroxide gel (Sigma) on days 0, 3 and 7 as previously described (19). 7 days following final sensitisation, mice were administered chemokine receptor antagonists (in 250µL endotoxin-free PBS) intravenously: 250µg MCPala/ala (scrambled peptide control) (20, 21), 100µg CCL206–70 (CCR6 antagonist) (21), 250µg CXCL114–79 (CXCR3 antagonist) (20), 250µg SB-328457 (CCR3 antagonist; Tocris Bioscience) (22) or PBS + 0.01% Tween 80 (vehicle for SB-328457). 1hr following treatment, mice were challenged intraperitoneally with 1mg OVA in 250µL endotoxin-free PBS. 6hrs post-challenge, draining lymph nodes, spleen, peripheral blood and peritoneal washes (4×1 mL PBS) were harvested and cells analysed by flow cytometry.

For generation of TH9 cells under autoimmune conditions, SJL/j mice were immunised subcutaneously in hind flanks with 100µg proteolipid protein (PLP)139–151 in 100µL CFA as previously described (21). On days 0 and 2, mice received 300ng pertussis toxin (List Biological Laboratories) in 250µL endotoxin-free PBS intravenously. Chemokine receptor antagonists were administered intraperitoneally every 48hrs beginning 8 days post-EAE induction (as above). 15 days post-induction, draining lymph nodes, spleen, peripheral blood and CNS (spinal cord and brain) were harvested and processed as previously described (21) and assessed by flow cytometry. The University of Adelaide institutional animal ethics committee approved all experimentation involving the use of animals.

In vitro T cell differentiation

Erythrocyte-lysed splenocytes were cultured in complete IMDM at 1×106 cells/mL in the presence of plate-bound anti-CD3 (10µg/mL) and soluble anti-CD28 (1µg/mL). Cytokines for TH1 and TH17 differentiation were as described (23); iTreg: TGF-β (10ng/mL), anti-IFN-γ (10µg/mL) and anti-IL-4 (10µg/mL); TH9: TGF-β (10ng/mL), IL-4 (10ng/mL), IL-2 (1U/mL) and anti-IFN-γ (10µg/mL); TH2: IL-4 (10ng/mL), IL-2 (1U/mL) and anti-IFN-γ (10µg/mL); TH0: anti-IFN-γ (10µg/mL) and anti-IL-4 (10µg/mL). Cytokines and neutralising antibodies were purchased from R&D and BD, respectively. Cells were cultured for 3 days and then restimulated for 4hrs with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, ionomycin and GolgiStop (BD) in complete IMDM before surface and intracellular staining.

Naïve T cell sorting, RNA extraction and RT-PCR

Naïve CD4+ T cells (CD4+CD8−CD44lo/−CD25−) were sorted from erythrocyte-lysed splenocyte suspensions using a FACSAria (BD) and differentiated into TH0 and TH9 cells as described above. Total RNA was extracted from these cells using the micro RNeasy Kit (Qiagen) as per manufacturer’s instructions with on-column RNase-free DNase I treatment (Qiagen) to remove contaminating genomic DNA. cDNA was synthesised from RNA using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche) and used as a template in reactions using LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I master mix (Roche) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Primers used in this study were as follows: CCR3: 5’-TTGCCTACACCCACTGCTGTAT-3’ (forward) and 5’-TTTCCGGAACCTCTCACCAA-3’ (reverse), CCR6: 5’-TCTGCACTAGTGAGAGTGTG-3’ (forward) and 5’-GTCATCACCACCATAATGTTG-3’ (reverse) and CXCR3: 5’-GTGCTAGATGCCTCGGACTT-3’ (forward) and 5’-GAGGCGCTGATCGTAGTTGG-3’ (reverse). Primers for the reference gene RPLP0 were 5’-AGATGCAGCAGATCCGCAT-3’ (forward) and 5’-GGATGGCCTTGCGCA-3’ (reverse). Relative level of chemokine receptor mRNA was calculated as 1/2ΔCT (ΔCT = CT of chemokine receptor – CT of RPLP0).

In vitro chemotaxis

Chemokines diluted in 150µL chemotaxis buffer (RPMI supplemented with 0.5% BSA/20mM HEPES) were added to lower chambers of 96 well-transwell chemotaxis plates (5µm pores; Corning). In some experiments, chemokine receptor antagonists were included in the bottom chamber. For naïve T cell migration, splenocyte preparations were cultured overnight in complete IMDM. For effector T cells, TH subsets were differentiated as described above. Cells were washed in chemotaxis buffer, loaded into upper chambers (5×105 cells in 50µL chemotaxis buffer/well) and incubated for 3hrs at 37°C. To enumerate TH cell migration, migrated cells were harvested from the bottom chamber and restimulated as described above prior to flow cytometric analyses. Migrated cells of interest were enumerated by flow cytometry using CaliBRITE beads (BD) as an internal reference.

Antibodies and Flow Cytometry

Cells were stained as previously described (23). For intracellular staining, the Cytofix/Cytoperm (BD) kit was used as per manufacturer’s instructions. In certain experiments, Live/Dead fixable blue dead cell kit (Invitrogen) was used to exclude dead cells. Cells were acquired using either a FACSCanto or LSR-II (BD) and analysed using FlowJo software (Treestar).

RESULTS

In vitro-generated TH9 cells express functional CCR3, CCR6 and CXCR3

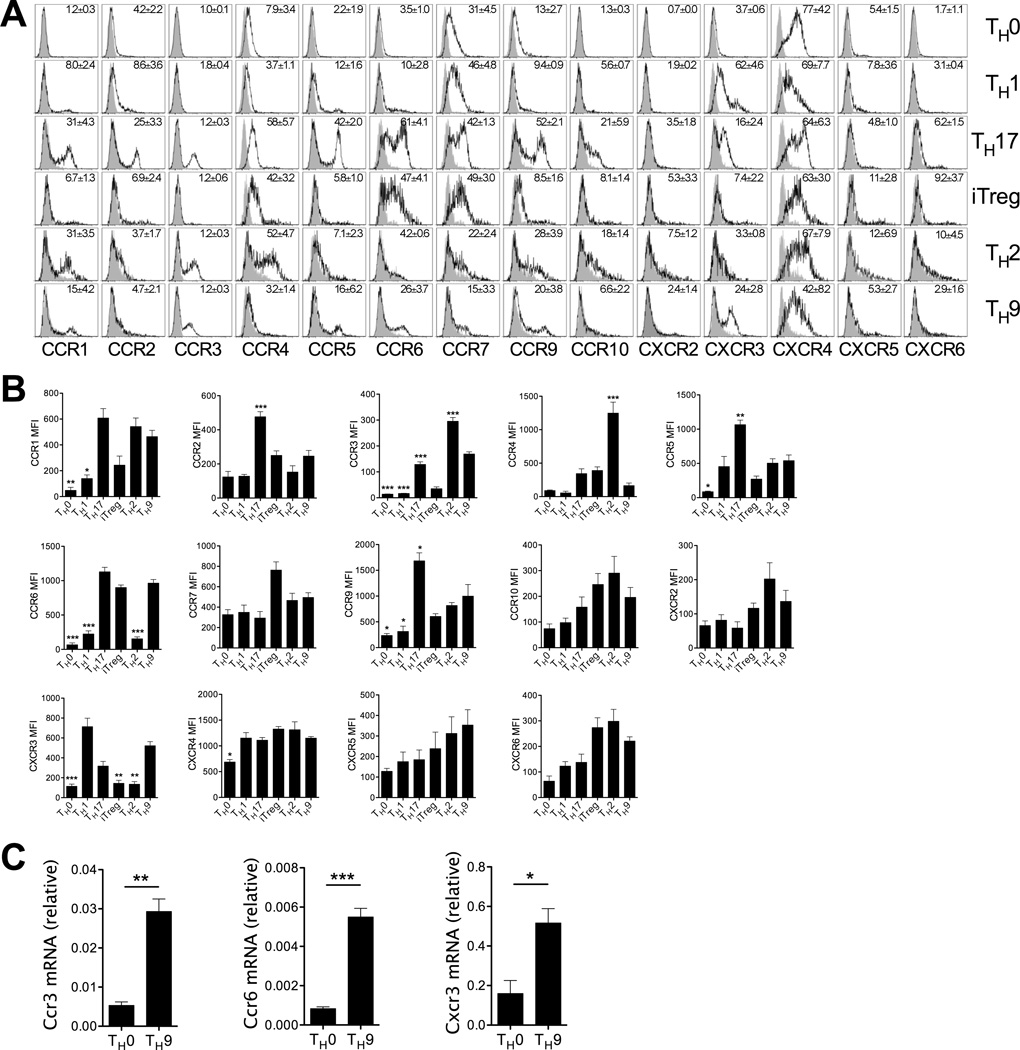

To assess the migratory capabilities of TH9 cells, chemokine receptor expression by in vitro generated TH9 cells was examined. Flow cytometric profiling of TH9 cells revealed protein expression of chemokine receptors characteristically associated with TH1 (CXCR3) (24), TH2 (CCR3) (24, 25) and TH17/iTreg (CCR6) (26) subsets, as well as chemokine receptors expressed by naïve and memory T cells (CCR7 and CXCR4) (Fig 1a,b) (17). CCR6, CXCR3 and CCR3 were also all elevated on TH9 cells relative to TH0 cells when mRNA levels were assessed using RT-PCR (Fig 1c). TH9 cells in these systems lacked detectable expression of CCR2, CCR4, CCR10, CXCR2 and CXCR6 (Fig 1a,b).

Figure 1. In vitro-generated TH9 cells express chemokine receptors associated with other effector TH cell subsets.

(A) Representative histograms of chemokine receptor expression on in vitro-generated TH cell subsets. Mean ± SEM over 3 independent experiments indicated within respective histograms. Grey histogram: isotype control; open histogram: anti-CKR staining. (B) Flow cytometric analyses of chemokine receptor mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) on in vitro-generated TH9 cells compared with TH0, TH1, TH17, iTreg and TH2 cells. Chemokine receptor MFI was calculated by subtracting respective isotype-matched negative control staining from anti-CKR staining MFI. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n=3 independent experiments). Comparisons of MFI on TH9 cells compared with other TH subsets were performed using a one-way ANOVA with a Bonferroni’s multiple comparison post-test. * denotes p<0.05; ** denotes p<0.01; *** denotes p<0.001. (C) Quantitative PCR analysis of Ccr3, Ccr6 and Cxcr3 mRNA expression by TH0 and TH9 cells generated from FACS-purified naïve CD4+ T cell precursors, presented relative to the house-keeping gene Rplp0. Data are presented as mean ± SD and are representative of one of two independent experiments performed with similar results. * denotes p<0.05; ** denotes p<0.01; *** denotes p<0.001.

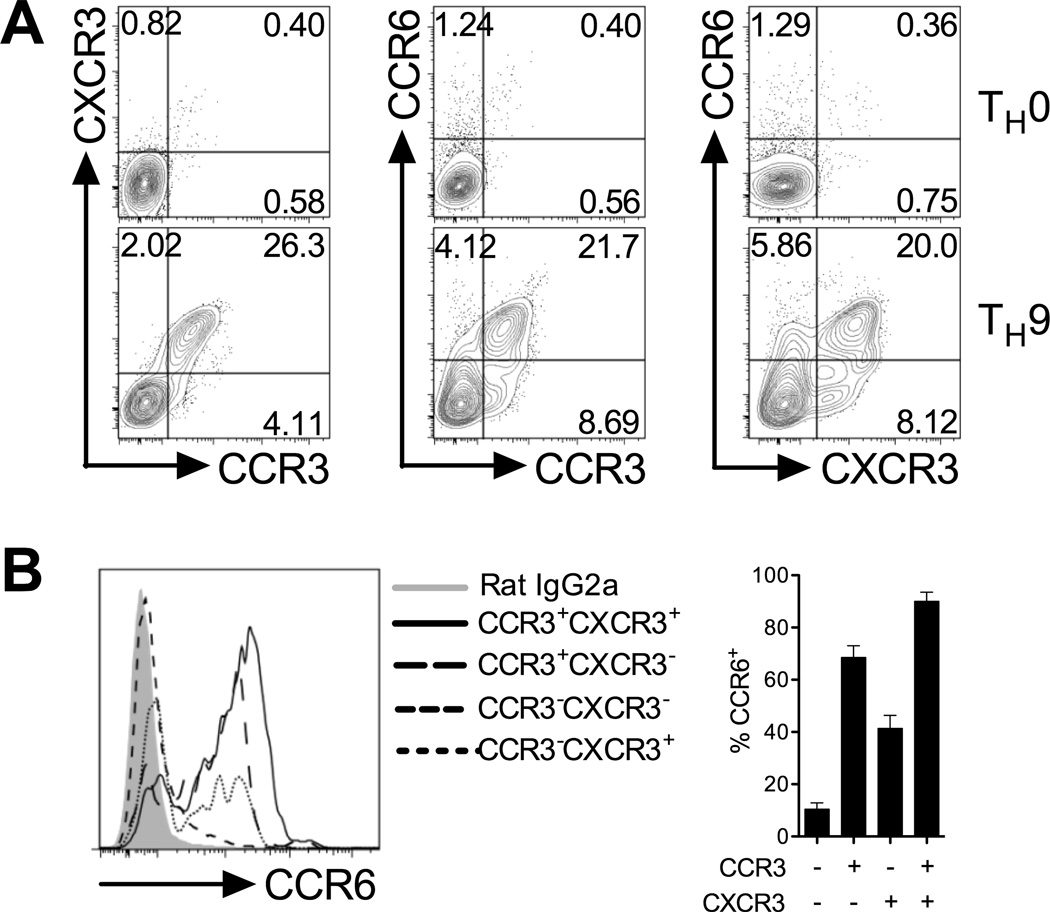

Multiple chemokine receptors coordinate migration of effector TH cells, and prior studies indicate that effector TH subsets co-express chemokine receptors with overlapping tissue-homing function (17). Thus, to determine if chemokine receptors were co-expressed or confined to distinct subsets of TH9 cells, a dual chemokine receptor staining strategy was employed. These experiments revealed that ~95% of CCR3+ TH9 cells co-expressed CXCR3, while >75% of CCR3+ TH9 cells were positive for CCR6 (Fig 2a). Triple chemokine receptor staining demonstrated that the majority of CCR6+ TH9 cells co-express CCR3 and CXCR3 (Fig 2b). Therefore, amongst the effector CD4+ T cell subsets identified to date, TH9 cells carry a unique chemokine receptor surface phenotype that may explain their participation in both autoimmunity and allergy.

Figure 2. In vitro-generated TH9 cells co-express CCR3, CCR6 and CXCR3.

(A) Representative FACS contour plots of dual chemokine receptor expression on TH0 and TH9 cells generated in vitro. (B) CCR6 expression on CCR3−CXCR3−, CCR3+CXCR3−, CCR3−CXCR3+ and CCR3−CXCR3+ TH9 cell populations. Quantitation is shown. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n=3 independent experiments). * denotes p<0.05; ** denotes p<0.01; *** denotes p<0.001.

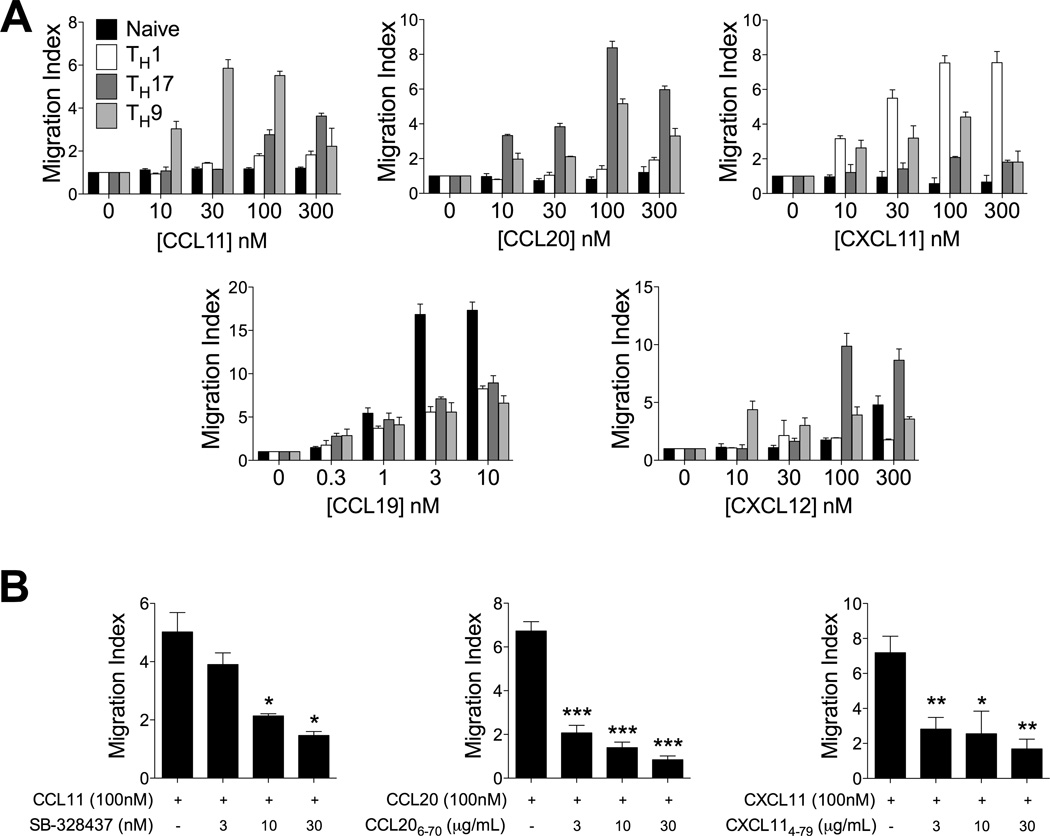

In vitro migration assays were performed to determine if CCR3, CCR6 and CXCR3 on TH9 cells were functionally active. Consistent with the high levels of surface expression of these receptors, efficient migration of TH9 cells toward CCL11, CCL20 and CXCL11 were measured (Fig 3a). Migratory responses of TH9 cells to CCL19 and CXCL12 were also observed, however these cells were substantially less responsive than naïve CD4+ T cells (to CCL19) and TH17 cells (to CXCL12) (Fig 3a). The specificity of these migratory responses of TH9 cells to CCR3, CCR6 and CXCR3 was confirmed using specific antagonists targeting these receptors. Treatment with the small molecule CCR3 antagonist SB-328437 inhibited TH9 migration toward CCL11, while the peptide antagonists CCL206–70 and CXCL114–79, efficiently prevented TH9 migration to CCL20 and CXCL11, respectively (Fig 3b).

Figure 3. Functional expression of CCR3, CCR6 and CXCR3 on TH9 cells.

(A) Transwell chemotaxis of TH9 cells relative to naïve, TH1 and TH17 cells. Migration index was calculated by dividing the number of positive events in test wells by the number of positive events in which no chemokine was added to the bottom chamber. Cells were enumerated as follows: naïve CD4+: CD4+CD8−CD62L+CD44lo; TH1: CD4+CD8−IFN-γ+IL-17A−; TH17: CD4+CD8−IFN-γ−IL-17A+; TH9: CD4+CD8−IFN-γ−IL-9+. Data presented as mean ± SEM (n=3 independent experiments). (B) Inhibition of TH9 cell migration to CCL11, CCL20 and CXCL11 using chemokine receptor antagonists. Migration assays were performed as in (A) with the inclusion of the indicated chemokine receptor antagonist in the lower chamber. Data presented as mean ± SEM (n=2 independent experiments). * denotes p<0.05; ** denotes p<0.01; *** denotes p<0.001.

Reports that chemokines promote proliferation and subsequent secretion of IFN-γ or IL-4 have demonstrated that chemokines may play important roles in T cell co-stimulation (27). Therefore, possible effects of these chemokines on TH9 differentiation were also examined. However, addition of CCL11, CCL20, or CXCL11 (or combinations of these chemokines), at concentrations known to activate their cognate receptors, to TH9-polarising T cell cultures did not alter TH9 differentiation in vitro (data not shown).

Collectively, these data indicate that TH9 differentiation is coupled with induction of a functional chemokine receptor repertoire that supports migration to chemokines commonly associated with type-1, -2 and type-17 inflammation.

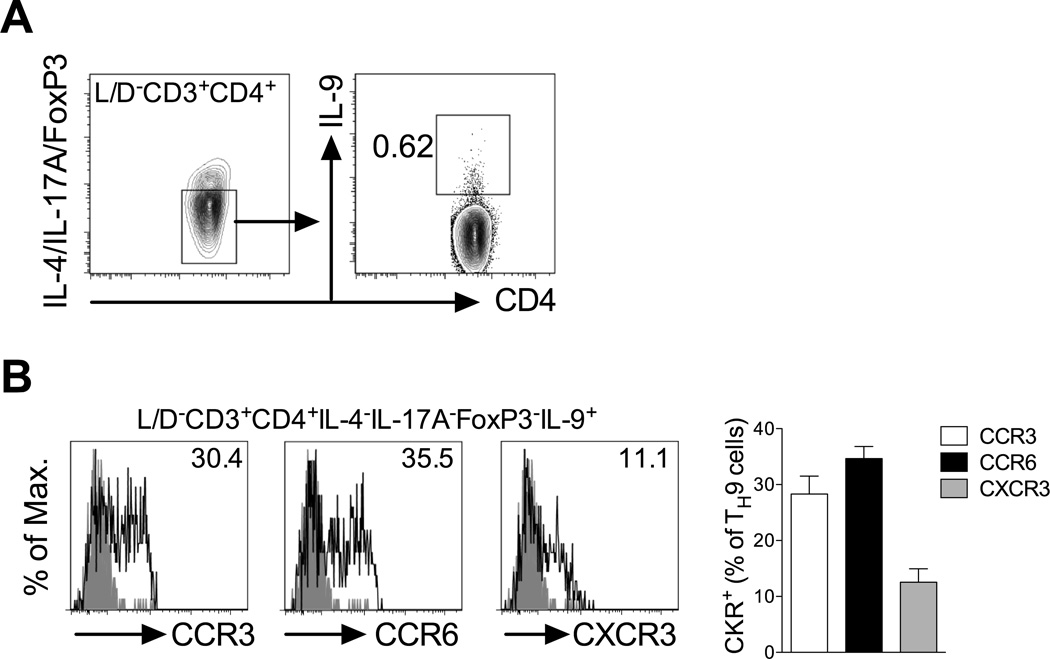

In vivo-generated TH9 cells express CCR3, CCR6 and CXCR3 in allergic and autoimmune inflammatory models

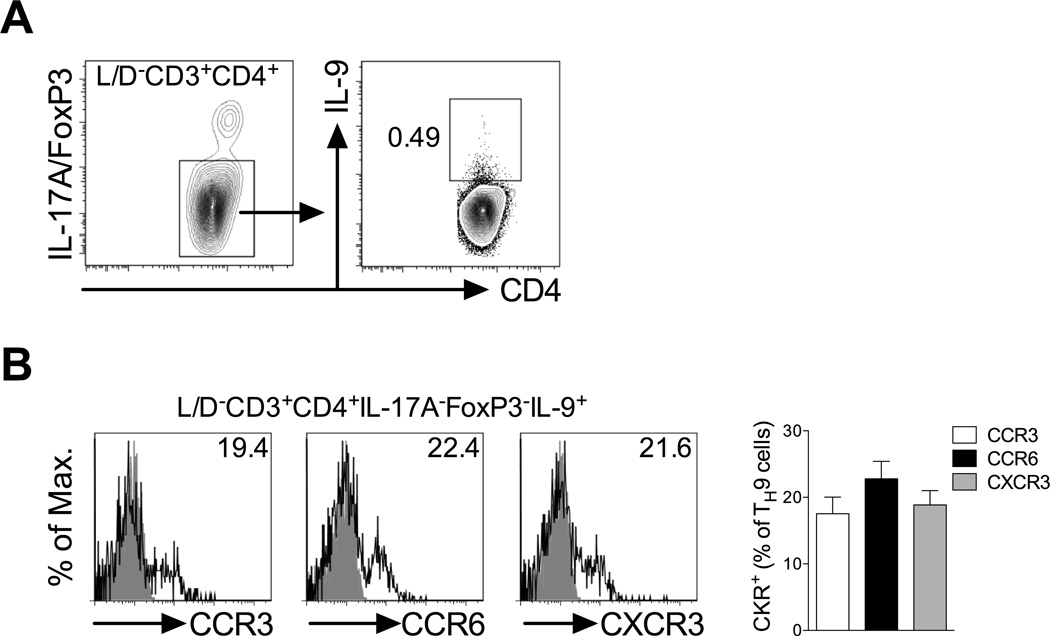

As TH9 cells are able to participate both in allergic (10, 11) and autoimmune inflammation (12), it was hypothesised that these cells differentially utilise chemokine receptors to migrate to allergic and autoimmune sites. Therefore, chemokine receptor expression on TH9 cells generated during models of experimental allergy and autoimmunity was investigated. Previous reports indicated that IL-9 can also be elicited, to some extent, from other TH subsets including iTreg, TH17 and TH2 cells (28). Therefore, to study bona fide TH9 cells in vivo, IL-9 was stained against a dump gate excluding IL-17A, FoxP3 and IL-4. Consistent with a previous study (19), multiple subcutaneous ovalbumin/alum immunisations in BALB/c mice, a classic type-2 priming model that leads to formation of TH2 cells and IgE (19), also led to generation of TH9 cells (CD3+CD4+IL-4−IL-17A−FoxP3−IL-9+) that could be detected in draining lymph nodes (Fig 4a). Analysis of chemokine receptor expression on these TH9 cells supported in vitro observations as TH9 cells generated in this model expressed CCR3, CCR6 and CXCR3 (Fig 4b).

Figure 4. TH9 cells generated in vivo during allergic inflammation express CCR3, CCR6 and CXCR3.

(A) Representative FACS contour plots of TH9 cells generated in a type-2 immunisation strategy. BALB/c mice were sensitised with OVA/AlOH gel on days 0, 3 and 7, inguinal lymph nodes collected 7 days later and TH9 cells identified in flow cytometry as live CD3+CD4+, IL-4/IL-17A/FoxP3− (bottom gate in left plot), IL-9+ (gated in right plot). (B) Representative FACS histograms of CCR3, CCR6 and CXCR3 expression on TH9 cells gated in (A) with % of chemokine receptor positive TH9 cells indicated. Grey histogram: isotype control; open histogram: anti-CKR staining. Quantitation is shown (n=5 mice).

Assessment of TH9 chemokine receptor expression generated under type-1/type-17 autoimmune conditions was initially examined using the MOG35–55-induced model of EAE in C57Bl/6 mice. However, in this model, IL-9+CD4+ T cells were not detected in draining lymph nodes or spleens on days 5, 9 or 12 post-immunisation (data not shown). Conversely, immunisation of SJL/j mice for PLP139–151-induced EAE, another type-1/type-17 priming model, led to generation of IL-9+CD4+ T cells that lacked IL-4, IL-17A and FoxP3 expression (Fig 5a and data not shown). Chemokine receptor expression profiling of TH9 cells generated under these conditions revealed that these cells also expressed CCR3, CCR6 and CXCR3 (Fig 5b).

Figure 5. TH9 cells generated in vivo during PLP-induced EAE express CCR3, CCR6 and CXCR3.

(A) Representative FACS contour plots of TH9 cells generated in a type-1/-17 immunisation strategy. SJL/j mice were immunised with PLP139–151/CFA, inguinal lymph nodes collected 10 days later and TH9 cells identified in flow cytometry as live CD3+CD4+, IL-17A/FoxP3− (bottom gate in left plot), IL-9+ (gated in right plot). (D) Representative histograms of CCR3, CCR6 and CXCR3 expression on TH9 cells gated in (B) with % of chemokine receptor positive TH9 cells indicated. Grey histogram: isotype control; open histogram: anti-CKR staining. Quantitation is shown (n=5 mice).

Differential chemokine receptor axes mediate recruitment of TH9 cells in allergic and autoimmune inflammatory settings

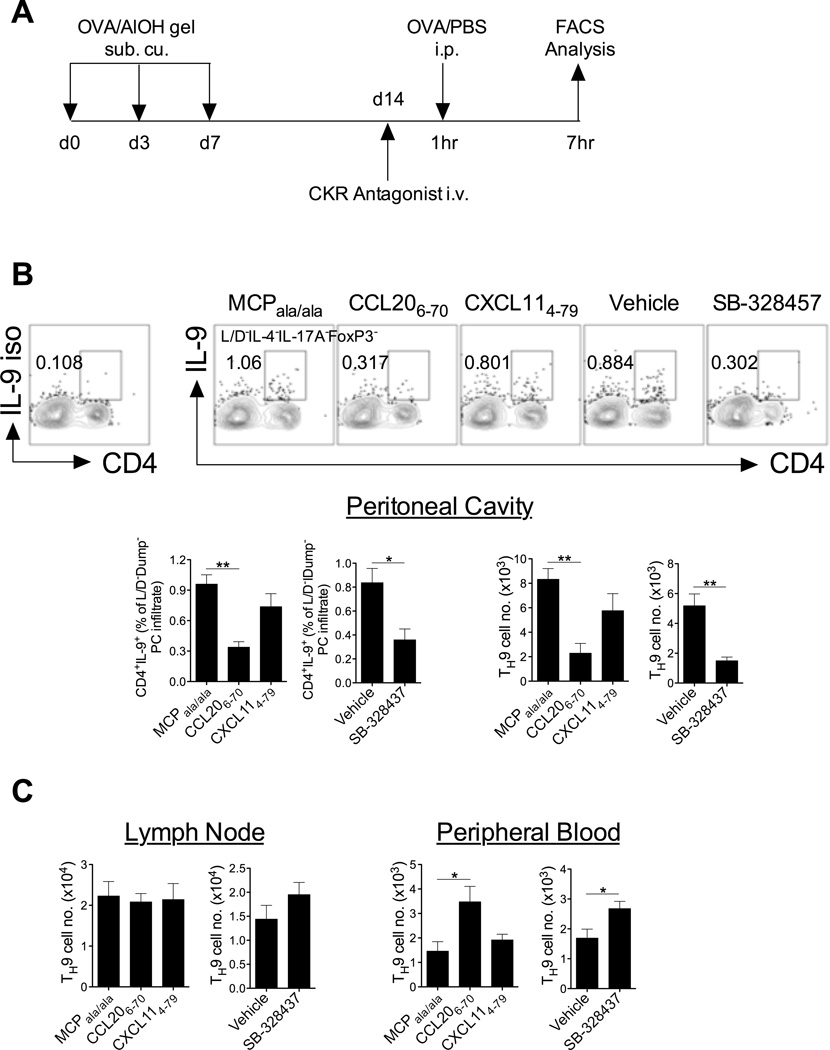

To investigate the contribution of these receptors to TH9 cell trafficking in vivo, chemokine receptor antagonists were administered during the effector phase of these models. The receptor antagonists have previously been shown to inhibit pathogenesis in animal models of allergic (29) and autoimmune (20, 21) diseases. Following OVA/alum sensitisation and subsequent intraperitoneal OVA/PBS challenge in a type-2 priming model (Fig 6a), antagonism of CCR3 or CCR6, using SB-328437 or CCL206–70 respectively, led to reduced frequencies of TH9 cells in the peritoneal cavity relative to control mice that were administered vehicle only or treated with a mis-folded chemokine peptide (MCPala/ala) (Fig 6b). In addition, treatment with the CCR3 and CCR6 antagonists resulted in accumulation of TH9 cells in the peripheral blood but not the draining lymph nodes (Fig 6c). No effect of CXCR3 antagonism using CXCL114–79 was observed in this model with regard to recruitment of TH9 cells to the peritoneal cavity, accumulation of TH9 cells in the peripheral blood or the draining lymph nodes in response to OVA challenge (Fig 6b,c). The reduced frequency of TH9 cells in the peritoneal cavity and increase of these cells in peripheral blood when CCR6 or CCR3 are antagonised strongly implicates these receptors as playing a role in blood to effector site trafficking in allergic inflammation. In these settings, CXCR3 does not appear to be of critical importance to TH9 homing. These findings are in keeping with previous findings that CCR6 and CCR3 ligands, but not CXCR3 ligands, are abundantly expressed at type-2 inflammatory sites (30, 31).

Figure 6. CCR3 and CCR6 mediate recruitment of TH9 cells to an allergic microenvironment.

(A) Schematic of experimental strategy. (B) Peritoneal cavity (PC)-infiltrated TH9 cells 6hrs post-OVA challenge. Representative FACS contour plots of peritoneal cavity-infiltrated TH9 cells (CD4+IL-9+) 6hrs post-OVA challenge. Plots are pre-gated on live IL-4/IL-17A/FoxP3 (Dump)− lymphocytes. Number and proportion of TH9 cells in the PC 6hrs post-OVA challenge is shown. (C) Number and proportion of TH9 cells 6hrs post-OVA challenge in lymph node and peripheral blood (live IL-4/IL-17A/FoxP3 (Dump)− lymphocytes that are CD4+IL-9+). Data presented as mean ± SEM (n=4 mice/group). Two tailed unpaired student t-tests were performed where appropriate. * denotes p<0.05; ** denotes p<0.01; *** denotes p<0.001.

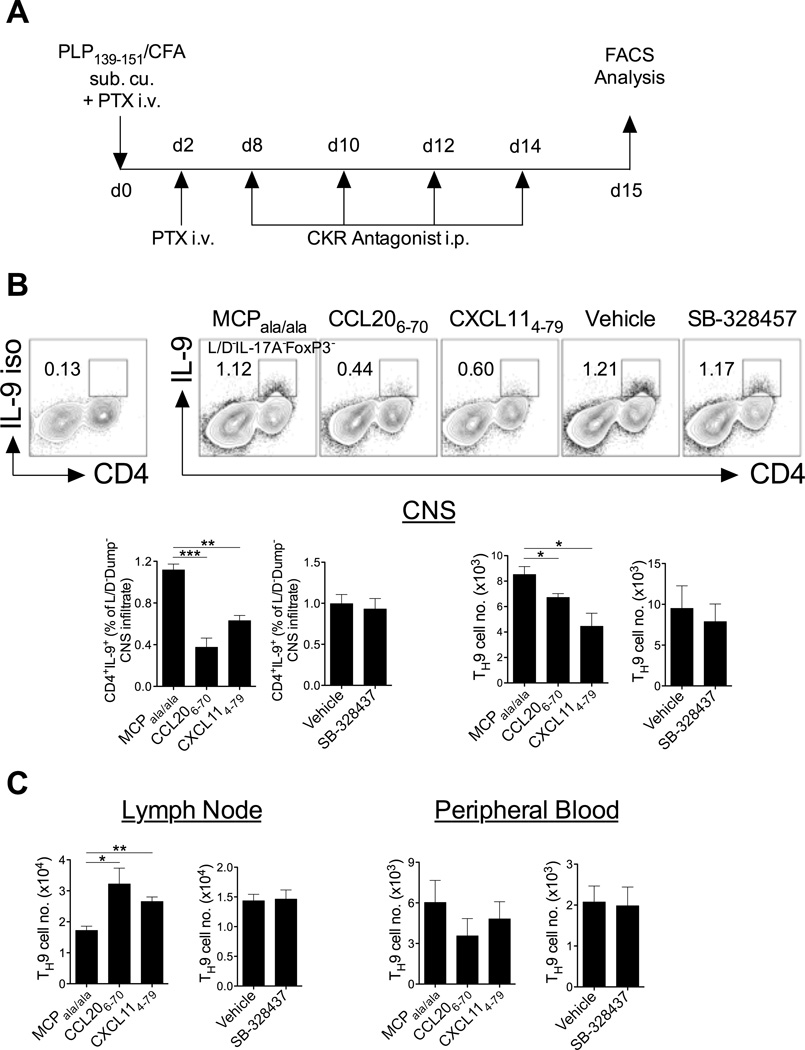

Conversely, chemokine receptor antagonism during PLP139–151-induced EAE (Fig 7a) revealed that antagonism of CXCR3 led to reduced recruitment of these cells to the CNS compared with control treated mice with a concomitant accumulation of TH9 cells in lymph nodes (Fig 7b,c). A similar effect was observed for CCR6 antagonism, which also led to reduced recruitment of TH9 cells to the CNS and accumulation of TH9 cells in lymph nodes (Fig 7b,c). In contrast to allergic inflammation, no effect of CCR3 antagonism was apparent on TH9 cell trafficking in the EAE model (Fig 7b,c). These data indicate that CCR6 and CXCR3 are likely to be involved in TH9 egress from lymph nodes during EAE and are important for recruitment of these cells to the CNS. These findings are consistent with previous reports demonstrating that both CCR6 and CXCR3 ligands are induced in the secondary lymphoid organs and CNS in EAE (32, 33).

Figure 7. CCR6 and CXCR3 mediate recruitment of TH9 cells to an autoimmune microenvironment.

(A) Schematic of experimental strategy. (B) CNS-infiltrated TH9 cells 15 days post-EAE induction. Representative FACS contour plots of CNS-infiltrated TH9 cells (CD4+IL-9+) on d15-post EAE induction. Plots are pre-gated on live IL-17A/FoxP3 (Dump)−. Number and proportion of TH9 cells in CNS d15 post-EAE induction is shown. (C) Number and proportion of TH9 cells in lymph node and peripheral blood (live IL-4/IL-17A/FoxP3 (Dump)− lymphocytes that are CD4+IL-9+). Data presented as mean ± SEM (n=3–4 mice/group). Two tailed unpaired student t-tests were performed where appropriate. * denotes p<0.05; ** denotes p<0.01; *** denotes p<0.001.

DISCUSSION

TH9 cells are the most recently described and least well understood subset of effector TH cells. In the present study, we have observed that in vitro and in vivo generation of TH9 cells is coupled with the upregulation of functional chemokine receptors commonly associated with other effector TH subsets including CCR3 (TH2) (24, 25), CCR6 (TH17/Treg) (26) and CXCR3 (TH1) (24). Using chemokine receptor antagonists, we have also demonstrated that TH9 cells utilise CCR3 and CCR6 to traffic to an allergic inflammatory site, whilst migration of these cells to an autoimmune effector site, is CCR6- and CXCR3-dependent.

Disrupting pathogenic effector TH cell migration in certain CD4+ T cell-driven pathologies through antagonism/neutralisation of specific chemokine receptors holds much promise for treatment of human disease (34). Central to the success of this approach is a greater understanding of the subsets of effector TH cells responsible for driving particular pathologies and identifying the unique homing signals used by these cells to infiltrate tissues. Previous studies have identified TH1 cells as carrying a CXCR3+CCR5+ phenotype (24, 35) with subpopulations also positive for CCR1 and/or CCR2 (24, 36). Characteristically, TH2 cells do not share any of these TH1 homing receptors and instead variously express CCR3, CCR4 and CCR8 on their cell surface (25, 37). These distinct chemokine receptor repertoires are thought to largely account for exclusive homing of these functionally antagonistic effector TH subsets to initiate macrophage-rich or eosinophil-rich inflammatory lesions, respectively. On the other hand, the apparently functionally opposing TH17 and Treg subsets share expression of the chemokine receptor CCR6 (26). This receptor facilitates recruitment of these cells to sites of CCL20 production, a chemokine that is expressed constitutively and whose expression is strongly upregulated during acute inflammation at epithelial and mucosal sites (38). Subsets of TH17 cells have also been variously reported to express CCR2, CCR4, CXCR4 and CXCR6 (39), while Treg function appears to additionally depend on CCR7 (40). It has been postulated that the balance between inflammatory TH17 cells and Tregs infiltrating a given inflammatory site dictates whether prolonged and perhaps pathological inflammation or response resolution occurs (38). The results of the present study indicate that in contrast to these other TH subsets, TH9 cells do not express chemokine receptors that are unique to the subset, but share chemokine receptors with other known subsets of TH cells.

Our results reveal several unique aspects of TH9 cells that may provide key information into understanding not only the migratory properties of these cells, but also with regard to their functional significance. Give that TH9 cells are equipped with trafficking receptors that facilitate migration to virtually any inflammatory lesion, we propose that these cells play an active role in cell-mediated, humoral and acute inflammatory responses. Indeed, IL-9 production has been detected in various human inflammatory settings including allergy (reviewed in (41)), IL-9 is also present in classic TH1 responses such as during Mycobacterium tuberculosis (42) and respiratory syncitial virus infection (43) and can be detected in murine models of TH1/TH17-driven human autoimmune disease such as EAE (13, 14). IL-9 has been shown to have pleitropic effector functions at these inflammatory lesions, including induction of various chemokines such as CCL20 from astrocytes during EAE (44), CCL11 in smooth muscle cells (45) and, in synergy with TNF-α, CXCL8 in the lung (46). Moreover, TH9 cells themselves have been shown to produce the CCR4 ligands CCL17 and CCL22 (11). Therefore, it is possible that TH9 cells may contribute to these various forms of inflammation by providing an adaptive immune source of IL-9, a cytokine that amplifies the chemotactic potential of an inflammatory site, facilitating the subsequent homing of innate effector cells and other effector T cell subsets. However, these hypotheses remain to be tested. Indeed, the functional significance of the TH9 subset has yet to be determined in detail and most insights to date have come from studies prior to the demonstration that these cells were a distinct differentiation lineage or where IL-9 blockade/deletion in all compartments has been employed. More refined studies taking advantage of T cell-specific PU.1 knockout mice (11) or the recently engineered IL-9 fate-mapping reporter mouse (47) will be required to address these issues in various inflammatory settings. Moreover, the question of plasticity of this subset remains. Recent studies using an IL-17 fate mapping strategy has revealed that TH17 cells convert to TH1 cells in vivo during the evolution of EAE (48), which presumably allows them to contribute to both the early antigen-specific adaptive response through inflammation and recruitment of neutrophils, and then to contribute to the cell-mediated immune response via the production of IFN-γ. A similar approach using the IL-9 fate-mapping reporter mouse could be employed to delineate the fate of TH9 cells in different types of immune responses.

Several other key findings related to TH9 cells are apparent from this study. It is of note that CCR6 and CXCR3 antagonism during EAE appeared to prevent TH9 cell egress from draining LNs into the peripheral blood, thereby inhibiting recruitment of the cells into the CNS. While a clear role for chemokine receptors in the promotion of egress of effector T cells from secondary lymphoid organs has yet to be formally demonstrated, these results are in keeping with our previous observations that CCR6 antagonism and neutralization of CCL20 increases the frequency of effector T cells in draining LNs during EAE and reduces their abundance in the circulation (21, 33). Egress of T cells from LNs is considered to be largely controlled by relative expression of the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor S1P1, which attracts cells into the peripheral blood, and CCR7, which retains cells in the LN (49). Our results suggest that inflammatory chemokine receptors such as CXCR3 and CCR6 can also contribute to TH cell egress from LNs. However, these effects appear to be model-dependent, as no effect of CCR6 or CXCR3 antagonism on TH9 cell accumulation in LN were apparent following immune priming in the OVA/alum model. Dissecting out the precise chemokine signals that promote effector TH cell egress from secondary lymphoid tissues in specific inflammatory settings may be a promising avenue of investigation given the therapeutic effectiveness, but also the generalised immune suppression, of S1P1 antagonism in humans (50).

In summary, the data presented in this manuscript are the first to define trafficking of TH9 cells and provide an explanation for the appearance and involvement of these cells in disparate forms of inflammation. TH9 cells express a broader range of functional chemokine receptors than other TH subsets, allowing migration to type-1, type-2 and type-17 inflammatory sites, where they have previously been implicated in T cell-driven pathology. These findings will be of importance to the design of therapeutic strategies to limit detrimental inflammation driven by pathogenic TH9 and other effector TH cells. However, further investigations using model systems in which these chemokine receptors have been specifically knocked out on TH9 cells will be required to unequivocally prove whether recruitment of TH9 cells by these specific receptors is required for disease pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the late Professor Ian Clark-Lewis for various chemokines and chemokine receptor antagonists.

Grant support: This work was supported by funding from the NH&MRC. I.C. is a recipient of funding from Multiple Sclerosis Research Australia. T.M.H. is supported by funds from the National Institute of Health (R01 AI37113).

Abbreviations

- AlOH

aluminum hydroxide

- CNS

central nervous system

- EAE

experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors disclose no competing financial interests.

Author contribution: E.E.K.: designed and performed research, analysed data and wrote the manuscript; I.C.: designed and supervised the study, performed research and wrote the manuscript; C.R.B., K.A.F. & W.L.: performed research; S.R.M.: designed and supervised the study, and wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Veldhoen M, Uyttenhove C, van Snick J, Helmby H, Westendorf A, Buer J, Martin B, Wilhelm C, Stockinger B. Transforming growth factor-beta 'reprograms' the differentiation of T helper 2 cells and promotes an interleukin 9-producing subset. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1341–1346. doi: 10.1038/ni.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dardalhon V, Awasthi A, Kwon H, Galileos G, Gao W, Sobel RA, Mitsdoerffer M, Strom TB, Elyaman W, Ho IC, Khoury S, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-4 inhibits TGF-beta-induced Foxp3+ T cells and, together with TGF-beta, generates IL-9+ IL-10+ Foxp3(-) effector T cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1347–1355. doi: 10.1038/ni.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jabeen R, Kaplan MH. The symphony of the ninth: the development and function of Th9 cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2012;24:303–307. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMillan SJ, Bishop B, Townsend MJ, McKenzie AN, Lloyd CM. The absence of interleukin 9 does not affect the development of allergen-induced pulmonary inflammation nor airway hyperreactivity. J Exp Med. 2002;195:51–57. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng G, Arima M, Honda K, Hirata H, Eda F, Yoshida N, Fukushima F, Ishii Y, Fukuda T. Anti-interleukin-9 antibody treatment inhibits airway inflammation and hyperreactivity in mouse asthma model. Am J Respir Criti Care Med. 2002;166:409–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2105079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kung TT, Luo B, Crawley Y, Garlisi CG, Devito K, Minnicozzi M, Egan RW, Kreutner W, Chapman RW. Effect of anti-mIL-9 antibody on the development of pulmonary inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in allergic mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2001;25:600–605. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.5.4533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angkasekwinai P, Chang SH, Thapa M, Watarai H, Dong C. Regulation of IL-9 expression by IL-25 signaling. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:250–256. doi: 10.1038/ni.1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monteyne P, Renauld JC, Van Broeck J, Dunne DW, Brombacher F, Coutelier JP. IL-4-independent regulation of in vivo IL-9 expression. J Immunol. 1997;159:2616–2623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gessner A, Blum H, Rollinghoff M. Differential regulation of IL-9-expression after infection with Leishmania major in susceptible and resistant mice. Immunobiology. 1993;189:419–435. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(11)80414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staudt V, Bothur E, Klein M, Lingnau K, Reuter S, Grebe N, Gerlitzki B, Hoffmann M, Ulges A, Taube C, Dehzad N, Becker M, Stassen M, Steinborn A, Lohoff M, Schild H, Schmitt E, Bopp T. Interferon-regulatory factor 4 is essential for the developmental program of T helper 9 cells. Immunity. 2010;33:192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang HC, Sehra S, Goswami R, Yao W, Yu Q, Stritesky GL, Jabeen R, McKinley C, Ahyi AN, Han L, Nguyen ET, Robertson MJ, Perumal NB, Tepper RS, Nutt SL, Kaplan MH. The transcription factor PU.1 is required for the development of IL-9-producing T cells and allergic inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:527–534. doi: 10.1038/ni.1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jager A, Dardalhon V, Sobel RA, Bettelli E, Kuchroo VK. Th1, Th17, and Th9 effector cells induce experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with different pathological phenotypes. J Immunol. 2009;183:7169–7177. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li H, Nourbakhsh B, Ciric B, Zhang GX, Rostami A. Neutralization of IL-9 ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by decreasing the effector T cell population. J Immunol. 2010;185:4095–4100. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li H, Nourbakhsh B, Cullimore M, Zhang GX, Rostami A. IL-9 is important for T-cell activation and differentiation in autoimmune inflammation of the central nervous system. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:2197–2206. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nowak EC, Weaver CT, Turner H, Begum-Haque S, Becher B, Schreiner B, Coyle AJ, Kasper LH, Noelle RJ. IL-9 as a mediator of Th17-driven inflammatory disease. J Exp Med. 2009;206:1653–1660. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tan C, Aziz MK, Lovaas JD, Vistica BP, Shi G, Wawrousek EF, Gery I. Antigen-specific Th9 cells exhibit uniqueness in their kinetics of cytokine production and short retention at the inflammatory site. J Immunol. 2010;185:6795–6801. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bromley SK, Mempel TR, Luster AD. Orchestrating the orchestrators: chemokines in control of T cell traffic. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:970–980. doi: 10.1038/ni.f.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Viola A, Molon B, Contento RL. Chemokines: coded messages for T-cell missions. Front Biosci. 2008;13:6341–6353. doi: 10.2741/3158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He SH, Liu ZQ, Chen X, Song CH, Zhou LF, Ma WJ, Cheng L, Du Y, Tang SG, Yang PC. IL-9(+) IL-10(+) T cells link immediate allergic response to late phase reaction. Clin Exp Immunol. 2011;165:29–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohler RE, Comerford I, Townley S, Haylock-Jacobs S, Clark-Lewis I, McColl SR. Antagonism of the chemokine receptors CXCR3 and CXCR4 reduces the pathology of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Brain Pathol. 2008;18:504–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liston A, Kohler RE, Townley S, Haylock-Jacobs S, Comerford I, Caon AC, Webster J, Harrison JM, Swann J, Clark-Lewis I, Korner H, McColl SR. Inhibition of CCR6 function reduces the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis via effects on the priming phase of the immune response. J Immunol. 2009;182:3121–3130. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0713169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.White JR, Lee JM, Dede K, Imburgia CS, Jurewicz AJ, Chan G, Fornwald JA, Dhanak D, Christmann LT, Darcy MG, Widdowson KL, Foley JJ, Schmidt DB, Sarau HM. Identification of potent, selective non-peptide CC chemokine receptor-3 antagonist that inhibits eotaxin-, eotaxin-2-, and monocyte chemotactic protein-4-induced eosinophil migration. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36626–36631. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haylock-Jacobs S, Comerford I, Bunting M, Kara E, Townley S, Klingler-Hoffmann M, Vanhaesebroeck B, Puri KD, McColl SR. PI3Kdelta drives the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis by inhibiting effector T cell apoptosis and promoting Th17 differentiation. J Autoimmun. 2011;36:278–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bonecchi R, Bianchi G, Bordignon PP, D'Ambrosio D, Lang R, Borsatti A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Gray PA, Mantovani A, Sinigaglia F. Differential expression of chemokine receptors and chemotactic responsiveness of type 1 T helper cells (Th1s) and Th2s. J Exp Med. 1998;187:129–134. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sallusto F, Mackay CR, Lanzavecchia A. Selective expression of the eotaxin receptor CCR3 by human T helper 2 cells. Science. 1997;277:2005–2007. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamazaki T, Yang XO, Chung Y, Fukunaga A, Nurieva R, Pappu B, Martin-Orozco N, Kang HS, Ma L, Panopoulos AD, Craig S, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, Tian Q, Dong C. CCR6 regulates the migration of inflammatory and regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:8391–8401. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.12.8391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taub DD, Turcovski-Corrales SM, Key ML, Longo DL, Murphy WJ. Chemokines and T lymphocyte activation: I. Beta chemokines costimulate human T lymphocyte activation in vitro. J Immunol. 1996;156:2095–2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noelle RJ, Nowak EC. Cellular sources and immune functions of interleukin-9. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:683–687. doi: 10.1038/nri2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mori A, Ogawa K, Someya K, Kunori Y, Nagakubo D, Yoshie O, Kitamura F, Hiroi T, Kaminuma O. Selective suppression of Th2-mediated airway eosinophil infiltration by low-molecular weight CCR3 antagonists. Int Immunol. 2007;19:913–921. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Francis JN, Sabroe I, Lloyd CM, Durham SR, Till SJ. Elevated CCR6+ CD4+ T lymphocytes in tissue compared with blood and induction of CCL20 during the asthmatic late response. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;152:440–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pease JE. Asthma, allergy and chemokines. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7:3–12. doi: 10.2174/138945006775270204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McColl SR, Mahalingam S, Staykova M, Tylaska LA, Fisher KE, Strick CA, Gladue RP, Neote KS, Willenborg DO. Expression of rat I-TAC/CXCL11/SCYA11 during central nervous system inflammation: comparison with other CXCR3 ligands. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1418–1429. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kohler RE, Caon AC, Willenborg DO, Clark-Lewis I, McColl SR. A role for macrophage inflammatory protein-3 alpha/CC chemokine ligand 20 in immune priming during T cell-mediated inflammation of the central nervous system. J Immunol. 2003;170:6298–6306. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viola A, Luster AD. Chemokines and their receptors: drug targets in immunity and inflammation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2008;48:171–197. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.121806.154841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loetscher P, Uguccioni M, Bordoli L, Baggiolini M, Moser B, Chizzolini C, Dayer JM. CCR5 is characteristic of Th1 lymphocytes. Nature. 1998;391:344–345. doi: 10.1038/34814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Colantonio L, Iellem A, Clissi B, Pardi R, Rogge L, Sinigaglia F, D'Ambrosio D. Upregulation of integrin alpha6/beta1 and chemokine receptor CCR1 by interleukin-12 promotes the migration of human type 1 helper T cells. Blood. 1999;94:2981–2989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D'Ambrosio D, Iellem A, Bonecchi R, Mazzeo D, Sozzani S, Mantovani A, Sinigaglia F. Selective up-regulation of chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR8 upon activation of polarized human type 2 Th cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:5111–5115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Comerford I, Bunting M, Fenix K, Haylock-Jacobs S, Litchfield W, Harata-Lee Y, Turvey M, Brazzatti J, Gregor C, Nguyen P, Kara E, McColl SR. An immune paradox: how can the same chemokine axis regulate both immune tolerance and activation?: CCR6/CCL20: a chemokine axis balancing immunological tolerance and inflammation in autoimmune disease. Bioessays. 2010;32:1067–1076. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lim HW, Lee J, Hillsamer P, Kim CH. Human Th17 cells share major trafficking receptors with both polarized effector T cells and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:122–129. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Menning A, Hopken UE, Siegmund K, Lipp M, Hamann A, Huehn J. Distinctive role of CCR7 in migration and functional activity of naive- and effector/memory-like Treg subsets. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1575–1583. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oh CK, Raible D, Geba GP, Molfino NA. Biology of the interleukin-9 pathway and its therapeutic potential for the treatment of asthma. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2011;10:180–186. doi: 10.2174/187152811795564073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ye ZJ, Yuan ML, Zhou Q, Du RH, Yang WB, Xiong XZ, Zhang JC, Wu C, Qin SM, Shi HZ. Differentiation and recruitment of Th9 cells stimulated by pleural mesothelial cells in human Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. PloS one. 2012;7:e31710. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dodd JS, Lum E, Goulding J, Muir R, Van Snick J, Openshaw PJ. IL-9 regulates pathology during primary and memory responses to respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Immunol. 2009;183:7006–7013. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou Y, Sonobe Y, Akahori T, Jin S, Kawanokuchi J, Noda M, Iwakura Y, Mizuno T, Suzumura A. IL-9 promotes Th17 cell migration into the central nervous system via CC chemokine ligand-20 produced by astrocytes. J Immunol. 2011;186:4415–4421. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gounni AS, Hamid Q, Rahman SM, Hoeck J, Yang J, Shan L. IL-9-mediated induction of eotaxin1/CCL11 in human airway smooth muscle cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:2771–2779. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baraldo S, Faffe DS, Moore PE, Whitehead T, McKenna M, Silverman ES, Panettieri RA, Jr, Shore SA. Interleukin-9 influences chemokine release in airway smooth muscle: role of ERK. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2003;284:L1093–L1102. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00300.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilhelm C, Hirota K, Stieglitz B, Van Snick J, Tolaini M, Lahl K, Sparwasser T, Helmby H, Stockinger B. An IL-9 fate reporter demonstrates the induction of an innate IL-9 response in lung inflammation. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1071–1077. doi: 10.1038/ni.2133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hirota K, Duarte JH, Veldhoen M, Hornsby E, Li Y, Cua DJ, Ahlfors H, Wilhelm C, Tolaini M, Menzel U, Garefalaki A, Potocnik AJ, Stockinger B. Fate mapping of IL-17-producing T cells in inflammatory responses. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:255–263. doi: 10.1038/ni.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pham TH, Okada T, Matloubian M, Lo CG, Cyster JG. S1P1 receptor signaling overrides retention mediated by G alpha i-coupled receptors to promote T cell egress. Immunity. 2008;28:122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolli MH, Lescop C, Nayler O. Synthetic sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulators--opportunities and potential pitfalls. Curr Top Med Chem. 2011;11:726–757. doi: 10.2174/1568026611109060726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]