Abstract

In both the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS), transected axons undergo Wallerian degeneration. Even though Augustus Waller first described this process after transection of axons in 1850, the molecular mechanisms may be shared, at least in part, by many human diseases. Early pathology includes failure of synaptic transmission, target denervation, and granular disintegration of the axonal cytoskeleton (GDC). The Ca2+-dependent proteases calpains have been implicated in GDC but causality has not been established. To test the hypothesis that calpains play a causal role in axonal and synaptic degeneration in vivo, we studied transgenic mice that express human calpastatin (hCAST), the endogenous calpain inhibitor, in optic and sciatic nerve axons. Five days after optic nerve transection and 48 hours after sciatic nerve transection, robust neurofilament proteolysis observed in wild-type controls was reduced in hCAST transgenic mice. Protection of the axonal cytoskeleton in sciatic nerves of hCAST mice was nearly complete 48 hours post-transection. In addition, hCAST expression preserved the morphological integrity of neuromuscular junctions. However, compound muscle action potential amplitudes after nerve transection were similar in wild-type and hCAST mice. These results, in total, provide direct evidence that calpains are responsible for the morphological degeneration of the axon and synapse during Wallerian degeneration.

Keywords: axon, calpain, calpastatin, neurofilament, neuromuscular junction, Wallerian degeneration

INTRODUCTION

In 1850, Augustus Waller made the seminal observation that after nerve transection, the distal portion undergoes progressive degeneration (Waller, 1850). Early pathological changes include failure of synaptic transmission, target denervation, and granular disintegration of the axonal cytoskeleton (GDC), in which neurofilaments, microtubules, and other cytoskeletal components appear to disintegrate (Miledi and Slater, 1970; Okamoto and Riker, 1969; Vargas and Barres, 2007). Even though Waller described this process after transection of axons, the molecular mechanisms may be shared, at least in part, by many human diseases, such as traumatic brain injury, cerebral ischemia, HIV dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and peripheral neuropathies (Coleman, 2005; Glass, 2004; Saxena and Caroni, 2007; Wang et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2012).

The mechanisms underlying Wallerian degeneration remain unclear, but evidence suggests that Ca2+ entry into the axoplasm with subsequent activation of calpains is the event triggering axonal degeneration (Coleman, 2005). Calpains are a family of Ca2+-dependent nonlysosomal proteases, and are known contributors to neuronal degeneration in traumatic brain injury, cerebral ischemia and Alzheimer’s disease (Saatman et al., 2010). Molecular mechanisms that mediate neuronal death e.g., caspases and the Bcl-2 family members Bax and Bak, are not necessarily responsible for the degeneration of the transected axon (Finn et al., 2000; Whitmore et al, 2003). Thus, examining pathologic changes in axons independent of the contributions from the neuronal somata, may be highly informative.

Evidence linking calpains to Wallerian degeneration primarily comes from in vitro studies using pharmacologic inhibitors. After neurite transection in dorsal root ganglia and sympathetic superior ganglia explant cultures, pharmacologic calpain inhibitors reduced degeneration of neurites (George et al., 1995; Wang et al., 2000; Zhai et al., 2003) and breakdown of neurofilaments (Finn et al., 2000). However, all of the calpain inhibitors that were used in these experiments inhibit other proteases (Goll et al., 2003; Saatman et al., 1996). In addition, in vitro studies must be interpreted cautiously as explants usually consist of developmentally young neurons lacking the complex supporting structures seen in vivo. Results from two in vivo studies (Couto et al., 2004; Glass et al., 2002) were inconclusive partly due to the limitations of the pharmacologic inhibitors used.

We hypothesized that calpains mediate Wallerian degeneration in the central and peripheral nervous systems. To capitalize on the complete specificity of the endogenous inhibitor calpastatin to calpains (Goll et al., 2003), we utilized adult transgenic mice that express human calpastatin (hCAST) within the axons of the optic and sciatic nerves. After axonal transection, biochemical, morphological and electrophysiologic outcomes were measured to assess the effect of intra-axonal calpain inhibition on Wallerian degeneration.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at the University of Pennsylvania, University of Kentucky, and Temple University.

Generation of human calpastatin expressing transgenic mice

The generation and initial characterization of the human calpastatin (hCAST) transgenic mice have been previously described (Schoch et al., in press). Mice were maintained as heterozygotes by breeding wild-type (WT) FVB/N females (Harlan Labs) with male hCAST heterozygotes. Mice positive for the hCAST gene were identified by PCR with primers 5’-GAACTGAACCATTTCAACCGAG-3’ and 5’-GCAGCTGTAGGCGACCCACAGGTGAAG-3’. For experimental procedures, adult male and female transgenic and WT littermates (4–6 months of age) were used. Transgenic mice displayed no overt phenotype with no change in basal levels of calpain proteases or various known substrates (Schoch et al., in press).

Immunohistochemistry of brain, retina, and nerves

Mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg intraperitoneal, IP) and xylazine (10 mg/kg IP). They were transcardially perfused with 1x phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB; pH 7.4). Brains were removed and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PB at 4°C for 6 hours prior to cryoprotection in graded concentrations of sucrose (10–30%). The eyecups, after removal of the lens, were post-fixed for 2–3 hours prior to cryoprotection in 30% sucrose. Optic and sciatic nerves were post-fixed for 1 hour, then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose. Twenty µm thick coronal sections of brains, 10 µm thick transverse sections of eye cups, and 10 µm thick longitudinal and cross-sections of nerves from WT and hCAST transgenic mice were cut on a cryostat. Brain and nerve sections were blocked in 3% normal goat serum and 0.1% Triton-X in 1x PBS for 30 min at room temp, while retinal sections were blocked in 10% normal goat serum, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 0.1% Triton-X for 1 hour. All sections were then incubated in their respective block solutions with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. The antibodies used for brain and retinal sections target neuron-specific class III β-tubulin (PRB-435P; 1:5000, Covance) and human calpastatin (MAB3084; 1:1000–4000; Millipore), while the antibodies for nerve sections target neuron-specific class III β-tubulin (Tuj1; 1:2000, Covance) and calpastatin (sc-20779; 1:250; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The following day, the sections were washed with 1x PBS, incubated with Alexa fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000–2000; Life Technologies) for 1 hour at room temp, and rinsed in 1x PBS. Retinal sections underwent an additional step and were stained in Hoechst 33342 solution (2.5 µg/ml; Sigma) and 0.05% Triton-X for 15 minutes at room temp, followed by 1x PBS rinses. Sections were coverslipped with Fluoromount G (Electron Microscopy Sciences), and viewed with a Leica DM4500B fluorescent microscope.

Immunohistochemistry of neuromuscular junctions

After euthanasia, mice were decapitated, and the levator auris longus and extensor digitorum longus muscles were carefully dissected from neck and leg, respectively, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PB (pH 7.4) for 20 minutes, followed by 1x PBS rinses. Immunolabeling for neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) in a whole mount muscle preparation was performed as described by Bauder and Ferguson (2012) using antibodies targeting neurofilament (SMI-312R; 1:1000; Covance), synaptic vesicles (SV2; 1:1000; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), and calpastatin (sc-20779; 1:100), and rhodamine-conjugated α-bungarotoxin (1:200; Sigma-Aldrich). The antibodies targeting neurofilament and synaptic vesicles were both visualized with either a fluorescein-conjugated or Cy-5-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:200). The calpastatin antibody was visualized using fluorescein-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (1:200). All three secondary antibodies are from Jackson ImmunoResearch. As neurofilament immunolabeling preferentially stains the pre-terminal axon and terminal arborization, the signal at the NMJ is mostly due to SV2 labeling. Confocal images were acquired using Nikon 80i epifluorescent microscope.

Ex vivo calpain inhibition assay of cortical homogenates

Under ketamine and xylazine anesthesia, WT and hCAST transgenic mice were decapitated and the brain removed and placed on ice. The cortex was isolated and sonicated on ice in 25 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1% CHAPS (pH 7.4). All samples were assayed in triplicate on the same microtiter plate. Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay. Reactions for calpain activity assay contained 100 µg of homogenized cortex, 5 nM µ-calpain (EMD Millipore) and 200 µM Suc-Leu-Tyr-MNA (MP Biomedicals) in a total volume of 200 µl. The room temperature reaction was started by adding CaCl2 to a final concentration of 5 mM. Time-dependent substrate hydrolysis was measured on a microplate reader (Turner Biosystems; 365 nm excitation, 410–460 nm emission). Fluorescent measurements were performed every 3 min over ~30 min. Proteolysis of Suc-Leu-Tyr-MNA results in increasing fluorescent signal.

In vitro calpain digest of optic and sciatic nerves

Optic and sciatic nerves were removed from 3 WT mice, pooled, and sonicated on ice in 25 mM HEPES, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.1% CHAPS (pH 7.4) with phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Protein concentration was determined using the Bradford assay. Reactions contained 1.9 µg/µl of nerve homogenates and a combination of 1 µM calpastatin peptide (EMD Millipore), which is encoded by exon 1B of the hCAST gene, 100 nM human erythrocyte µ-calpain (EMD Millipore), or 100 nM recombinant m-calpain (EMD Millipore). The room temperature reaction was started by adding CaCl2 (or equal volume of water) to a final concentration of 5 mM. Reactions were stopped at designated times by adding 2x loading buffer and heating to 95°C for 5 min.

Unilateral optic nerve transection

Adult mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg IP) and xylazine (10 mg/kg IP), pretreated with buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg IP) and placed on a heating plate. Bupivacaine anesthetic drops were applied to the eyes. Under a binocular operating microscope, the conjunctiva was separated from the sclera superiorly and the optic nerve exposed by blunt dissection. The optic nerve was transected ~1 mm behind the globe using Vannas spring scissors (Fine Science Tools). Erythromycin ophthalmic ointment was applied to both eyes. Mice received buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg IP) every 12 hours for up to a total of 4 additional doses.

Unilateral sciatic nerve transection

Sciatic nerve transection was performed immediately after optic nerve transection or after a delay of 72 hours. For electrophysiological and NMJ experiments, the animals did not receive optic nerve transection. The lower back was shaved and cleaned with betadine. The skin was incised, and the sciatic nerve was exposed by blunt dissection and transected at the internal obturator tendon using Vannas spring scissors. For longer survival times, a 10-0 ligature was applied to the proximal stump, and sutured to the surrounding tissue to prevent axonal growth into the distal segment. The skin was then sutured. Mice received buprenorphine every 12 hours for up to a total of 4 additional doses.

Western blot of optic and sciatic nerves

Under ketamine and xylazine anesthesia, mice were decapitated. The optic nerve, after discarding the proximal ~0.5 mm (the transection site) to eliminate the local effects of trauma from the scissors, was sonicated in 50 mM Tris (pH 7), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton-X, and 2 mM EGTA. Approximately 8.5 mm of the sciatic nerve distal to the transection site was removed from the body. The proximal ~1 mm (the transection site) was discarded, and the remaining nerve was sonicated in 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 1% SDS, and 2 mM EDTA. The sciatic nerve homogenate was centrifuged at 16100g at 4°C for 15 minutes, and the supernatant used for Western blot. Centrifugation was not performed on sciatic nerves processed for in vitro calpain digest so for that experiment, homogenates were used for Western blot. Corresponding lengths of contralateral nerves were used as uninjured controls. Both buffers contained protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche).

Protein concentration was quantified using Bradford assay. Proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE on a 4–20% Tris-glycine gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and probed for neurofilament light (NFL; PRB-574C; 1:20000; Covance), neurofilament heavy (NFH; N52; 1:1000; Sigma), calpastatin (sc-20779; 1:1000), or glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; PA1-988; 1:1000; Thermo Scientific). Blots were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence substrate were from Perkin Elmer. For blots probed for neurofilament, amido black staining was performed for loading control.

Ultrastructural analysis of nerves

Anesthetized mice were transcardially perfused with 2% paraformaldehyde and 2% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M PB (pH 7.4). The nerves were quickly removed, and then post-fixed in perfusate solution for at least 4 hours at 4°C. Nerves were osmicated and dehydrated. They were treated twice with propylene oxide for 5 min, incubated sequentially with Embed 812:propylene oxide mixtures (1:1 and 2:1), and incubated in pure Embed 812 mixture (Electron Microscopy Sciences) overnight. Tissues were then embedded in fresh Embed 812 mixture at 60°C for 48 hr. For light microscopy, cross-sections were cut at a thickness of 1 µm on an American Optical Reichert Ultracut Ultra microtome, and stained with alkaline toluidine blue. For electron microscopy, cross-sections were cut at a thickness of 90 nm, mounted on a 2×1 single slot formvar-carbon coated grid (Electron Microscopy Sciences), and stained with lead citrate and uranyl acetate.

Nerve cross-sections were imaged using a FEI Tecnai 12 electron microscope equipped with a Gatan 895 US1000 2k × 2k CCD camera. Optic nerves were analyzed 0.5 mm from the optic chiasm, while sciatic nerves were analyzed 8.5 mm distal to transection. Systematic sampling of the nerve cross-sections as previously described by Ma and colleagues (2009) was performed with minor modifications. For the scoring of optic nerves, images were captured at 3200x mag at 40 µm intervals across and down the nerve. Sciatic nerve images were captured at 3200x mag at 30 µm intervals. The contralateral uninjured side was used as controls.

Optic nerve scoring (5 days post-transection)

Using Adobe Photoshop, a counting frame (as described by Gundersen and colleagues, 1988) was overlaid on each image, and an observer blinded to injury and genotype counted myelinated axons with cytoskeletal preservation. Axons were counted as intact if (1) the visible axoplasm had cytoskeletal preservation, and (2) <25% of the cross-sectional area was filled with electron-dense material (“dark degeneration”). “Dark degeneration” is commonly seen after transection of optic nerve axons (Bignami et al., 1981; Marques et al., 2003; Narciso et al., 2001). Axons undergoing significant “dark degeneration” were not counted as intact because the integrity of the axonal cytoskeleton could not be reliably assessed. Myelin integrity was not a consideration. The area of the optic nerve cross-section was determined using NIH ImageJ, and numbers were reported as total axons per nerve. Approximately 2% of the nerve cross-section was scored.

Sciatic nerve scoring (48 hours and 5 days post-transection)

Because myelinated axons in sciatic nerve are significantly larger than those in optic nerves, one or a few axons are in view at 3200x mag. Therefore, when sampling the sciatic nerve cross-section, at each 30-µm interval, a myelinated axon was selected for scoring based on proximity to a superimposed point. The selected axon was moved to the center of the viewing frame and imaged. This process was repeated until the entire cross-sectional area was systematically sampled, as described above. Using Gatan DigitalMicrograph, an observer blinded to injury and genotype scored the axons. A myelinated axon was scored as intact if there was uniform, regularly spaced cytoskeleton in at least 50% of the visible axoplasm. Neither myelin integrity nor axoplasmic shrinkage was considered in the scoring of axons. The percent of myelinated axons that were intact is reported. About 80–150 axons were scored per sciatic nerve.

Scoring of neuromuscular junctions

For both semi-quantitative and quantitative scoring methods, NMJs were sampled from throughout the entire length of the muscle after visualization with pre- and post-synaptic markers as previously described (Bauder and Ferguson, 2012). The contralateral uninjured side was used as controls.

For semi-quantitative assessment, ~125–150 NMJs were scored by an observer blinded to genotype, using a Nikon 80i epifluorescent microscope (400x mag). NMJ innervation (percentage coverage of α-bungarotoxin with SMI-312R/SV2 staining) were visually estimated and classified as (1) complete, (2) ≥50% but not complete, (3) <50% but not absent, and (4) absent. As NMJs found deeper within muscle may be poorly labeled by antibody, only those NMJs found on the surface of the muscle were scored.

For quantitative assessment, NMJs were captured at 400x mag. Images were subsequently enlarged by 200% prior to manual tracing of the pre-synaptic area (visualized by SMI-312R/SV2 labeling) and post-synaptic area (visualized by α-bungarotoxin) by an observer blinded to genotype (Nikon Imaging Software-Elements). A ratio of pre-synaptic area to post-synaptic area was determined for each NMJ. Three to 8 NMJs per muscle were scored (n=5–6 mice/group). To ensure that the documented protective effect of hCAST was not due to a technical problem with antibody penetration, NMJs without any appreciable SMI-312R/SV2 signal were excluded from analysis. As above only NMJs found on the muscle surface were scored.

Electromyography

Fourteen hours after unilateral sciatic nerve transection, electromyography, using a Nicolet/VIASYS Viking Quest machine, was performed as described by Osuchowski and colleagues (2009) with minor modifications. Mice received IP ketamine and xylazine and were placed on a heating plate. Rectal temperature was maintained >35°C. For stimulation, 1-cm stainless steel electrodes were placed subdermally: the anode just lateral to the midline, with the tip inserted 1 mm caudal to the tail-base and advanced parallel to the spine, and the cathode ~3 mm lateral and parallel to the anode. One-cm subdermal needles inserted in the proximal thigh and into the heel served as the ground and reference electrodes, respectively. Recordings were obtained using a 9.5-mm gold plated ear clip electrode (Electrode Store), which was coated with an electrode gel and placed over the distal foot. This location likely resulted in recordings from multiple small foot muscles. Each animal was stimulated with incremental impulse intensity until a maximal and artifact-free compound muscle action potential (CMAP) motor response was evoked. Manipulating the recording electrode was performed to ensure maximal CMAP. The contralateral uninjured side was also studied, and served as an internal control. This cohort of mice was subsequently euthanized four hours after performance of electromyography for morphological analysis of the NMJs.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-tests were used to analyze the slopes (fluorescence over time) obtained in the calpastatin activity assay, the percent intact axons 5 days after sciatic nerve transection, and the quantitative NMJ data. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In all other analyses, analysis of variance (ANOVA) in repeated measures was performed. A p-value <0.05 for main effects and <0.2 for the interaction spaces were considered statistically significant. Pairwise comparisons were specified a priori and were accomplished using the t-test within the ANOVA (pooled variance). Significance levels for pairwise comparisons were adjusted for by using the Bonferroni correction. For the semiquantitative NMJ innervation data, there were four pre-planned comparisons: injured WT versus hCAST mice in each of the four categories of NMJ innervation. For these 4 pairwise comparisons a p<0.0125 was considered significant. In the other analyses, there were three pre-planned comparisons: uninjured WT versus uninjured hCAST, uninjured versus injured WT, and injured WT versus injured hCAST. For these 3 pairwise comparisons a p<0.017 was considered significant. Data are presented as means and standard deviations. All data were analyzed using SAS statistical software (Version 9.3, SAS Institute).

RESULTS

Characterization of human calpastatin transgenic mice

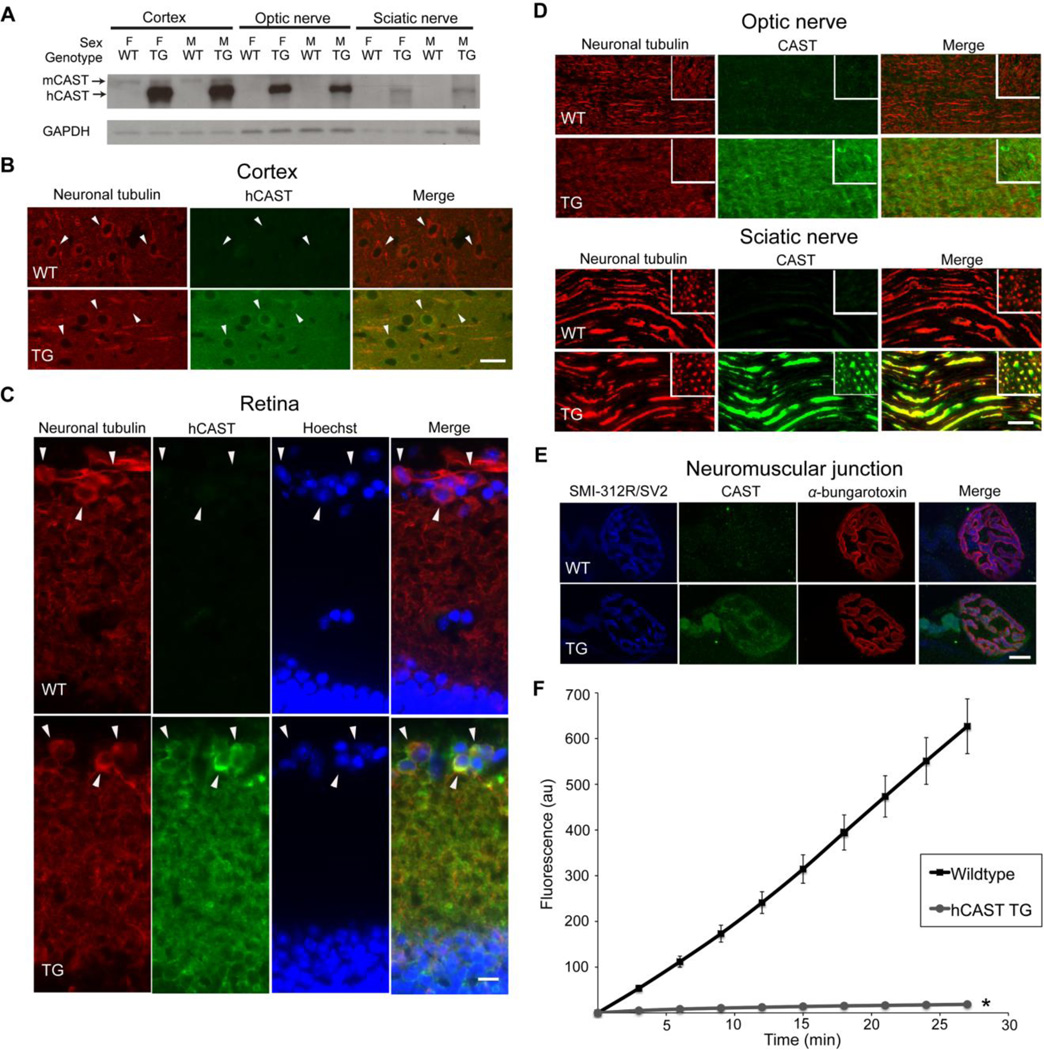

We characterized expression of the hCAST protein in the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral nervous system (PNS) by performing western blots of cortical and optic nerve homogenates, and sciatic nerve supernatants using an antibody (sc-20779) that detects calpastatin of both mouse and human origin (Figure 1A). There was high expression of hCAST in all three tissues from transgenic mice. Human calpastatin was not detectable in any tissue from WT littermates. However, a faint band, corresponding to mouse calpastatin (Schoch et al., in press), was seen in cortices from both WT and hCAST mice. The inability to detect mouse calpastatin in nerves is likely due to lower levels of expression.

Figure 1. Characterization of the human calpastatin transgenic mice.

(A) Western blot of cortical and optic nerve homogenates and sciatic nerve supernatants (12 µg load) of human calpastatin (hCAST) transgenic (TG) mice and wild-type (WT) littermates was probed with antibodies targeting calpastatin (CAST; sc-20779) and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH). Calpastatin of mouse origin (mCAST) has a slightly slower mobility than hCAST (Schoch et al., in press). Other abbreviations: M, male; F, female. (B) Coronal sections of the cortex were immunostained for neuron-specific class III β-tubulin and hCAST (MAB3084). Cortical neurons are indicated by arrowheads. Scale bar=25 µm. (C) Transverse sections of retina were double immunolabeled with class III β-tubulin and hCAST antibodies and counterstained with nuclear Hoechst. Cells positive for the retinal ganglion cell marker, class III β-tubulin (Cui et al., 2003; Kwong et al., 2011), are indicated by arrowheads. Scale bar=10 µm. (D) Longitudinal and cross-sections (inset) of optic and sciatic nerves were immunostained for neuron-specific class III β-tubulin and CAST. Scale bar=25 µm. (E) Representative images of neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) from levator auris longus muscle stained with SMI-312R/SV2 antibodies (preterminal axons and the presynaptic compartment), α-bungarotoxin (postsynaptic membrane), and CAST antibody. Scale bar=10 µm. (D) Ex vivo analysis for functional hCAST in cortical homogenates from TG mice compared to WT littermates. When WT cortical homogenates (n=5) were added to the reaction mix, increased fluorescent signal from proteolysis of the calpain substrate Suc-Leu-Tyr-MNA was evident. However, the addition of TG cortical homogenates (n=5) robustly inhibited proteolysis of the fluorogenic substrate. Error bars represent SD. *p<0.0001 compared to WT. In TG mice, hCAST is functional and is present in the axonal compartment and synapse.

We then performed immunohistochemistry to confirm our western blot results and further localize the hCAST protein. Human calpastatin protein, which colocalized with neuron-specific class III β-tubulin, was detectable in cortical neurons and neuropil (Figure 1B), retinal ganglion cell (Figure 1C), and optic and sciatic nerve axons (Figure 1D) in hCAST mice. In sciatic nerves, hCAST protein was readily apparent in myelinated axons, which, in the adult mouse, have mean cross-sectional areas ~19 fold larger than that of unmyelinated axons (Okada et al., 1975). In transgenic, but not WT mice, hCAST was detected in pre-terminal axons and neuromuscular junctions in levator auris longus (Figure 1E) and extensor digitorum longus muscles (data not shown).

The functionality of hCAST was assessed using a fluorogenic substrate microplate assay (Figure 1F). We compared cortical homogenates from hCAST mice with their WT littermates. Homogenates from hCAST mice robustly inhibited exogenous calpain activity (p<0.0001 compared to WT mice). Omitting exogenous calpain resulted in a slight increase in fluorescence over baseline in WT homogenates, likely due to the presence of endogenous calpains (data not shown). In the presence of exogenous calpain, either omitting the fluorogenic substrate or CaCl2 resulted in no change of fluorescence over time (data not shown). In summary, hCAST protein was robustly expressed in the somata of cortical neurons and retinal ganglion cells, and optic and sciatic nerve axons, and retained its ability to inhibit calpains.

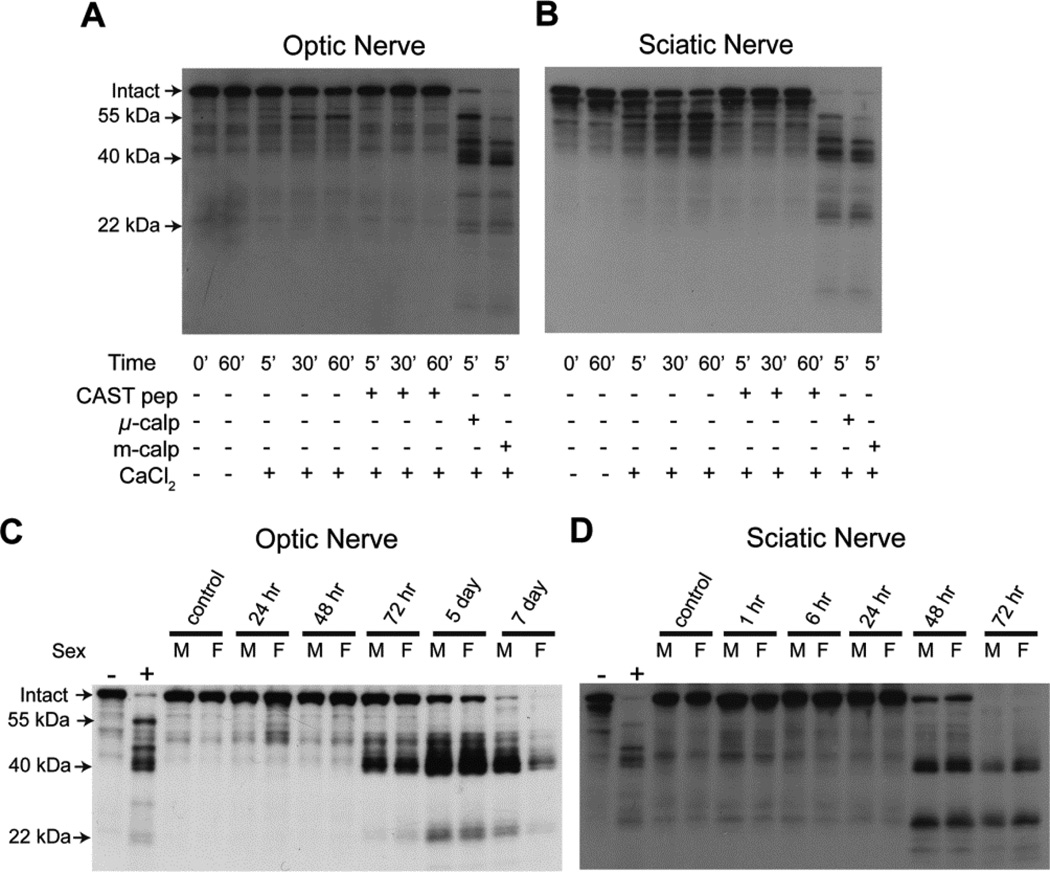

In vitro calpain digest of optic and sciatic nerves

Loss of intact neurofilaments, which are well-known calpain substrates (Zimmerman and Schlaepfer, 1982), is a commonly used outcome measure for axonal degeneration. We explored the potential of using neurofilament subtype proteolysis as a “signature” of axonal calpain activity. Calpain activity is recognized by both its absolute dependence on Ca2+ and inhibition by calpastatin. Calpastatin is completely specific for calpains and does not inhibit proteases from other families (Goll et al., 2003). Using an antiserum against full-length recombinant mouse neurofilament light (NFL), we identified multiple NFL fragments in calpain digests of optic and sciatic nerves from WT mice (Figure 2A and B). Endogenous calpain activity resulted in time-dependent loss of intact NFL and generation of a ~55 kDa fragment. Both the loss of intact and generation of the ~55 kDa fragment was completely blocked by 1 µM calpastatin peptide. The addition of either exogenous µ- or m-calpain (5 nM) accelerated the loss of intact NFL and generated the ~55 kDa fragment as well as several lower molecular weight fragments, notably at ~22 and ~40 kDa.

Figure 2. In vitro and in vivo proteolysis of neurofilament light.

Homogenized optic nerves (A) and sciatic nerves (B) from wild-type (WT) mice were added to in vitro reactions containing a combination of calpastatin peptide (CAST pep), exogenous µ-calpain (µ-calp), exogenous m-calpain (m-calp), or CaCl2. Reactions were stopped at specified time points. Western blot was performed using an antiserum against full-length recombinant mouse neurofilament light (NFL). Calpain proteolysis resulted in loss of intact NFL, as well as generation of fragments with molecular weights of ~55, ~40, and ~22 kDa. For (C) and (D), WT mice underwent unilateral transection of optic nerves (C) and sciatic nerves (D) and were sacrificed at the indicated times. The two left-most lanes of each blot are controls in which optic or sciatic nerve homogenates underwent in vitro calpain digest. The “−” represents time 0 for the reaction in which CaCl2 was omitted, while “+” was stopped 5 minutes after adding CaCl2 and exogenous calpain. Western blot was performed using an antiserum against NFL. Other abbreviations: M, male; F, female. Both optic and sciatic nerve transection resulted in NFL proteolysis, which generated fragments with similar sizes (~40 and ~22 kDa) to those seen with the in vitro calpain digest. The latency period was longer after optic nerve transection.

Time course of axonal degeneration after optic and sciatic nerve transection

Our next step was to determine the optimal in vivo time point to compare axonal degeneration in the CNS and PNS in hCAST versus WT mice. We performed unilateral transection of optic and sciatic nerves in WT mice, and euthanized them at predetermined intervals. Western blot analysis demonstrated significant loss of intact NFL 5 days after optic nerve transection and 48 hours after sciatic nerve transection (Figure 2C and D). The NFL fragments generated are of similar sizes as those seen in the in vitro calpain digest of nerve homogenates (two far left lanes). The ~22 and ~40 kDa fragments were the most prominent. The ~55 kDa fragment was not consistently seen in degenerating optic or sciatic nerves, and may represent a less stable transition fragment. To measure the effect of hCAST on axonal degeneration, we chose to examine optic and sciatic nerves 5 days and 48 hours after transection, respectively.

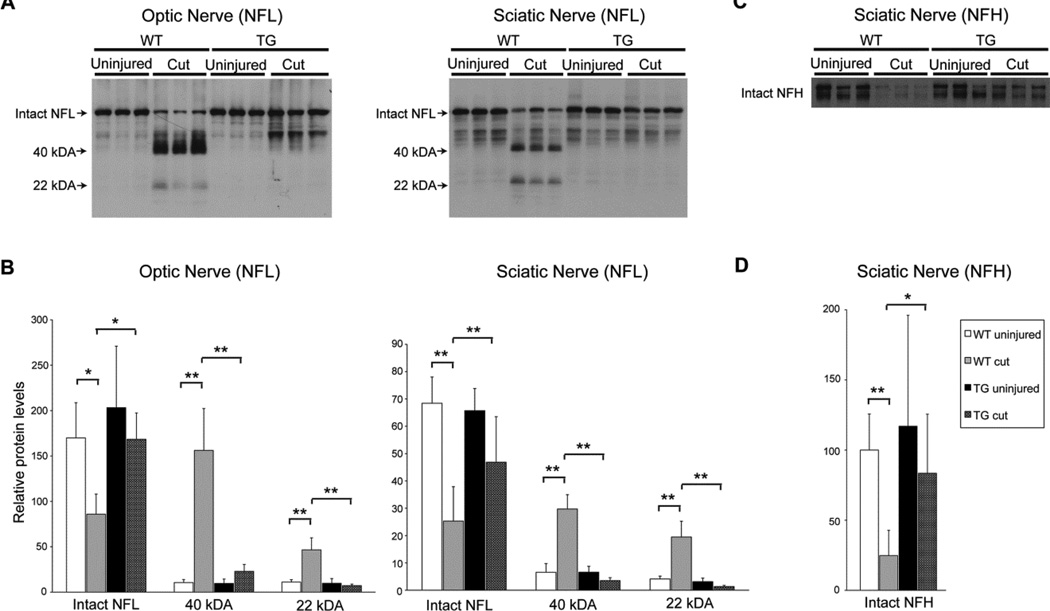

Effect of human calpastatin expression on neurofilament proteolysis

Human calpastatin transgenic mice and their WT littermates underwent unilateral optic nerve transection. In a subpopulation of mice, this was followed 72 hours later by unilateral sciatic nerve transection. Transecting optic nerves prior to sciatic nerve transection did not affect NFL proteolysis in sciatic nerves (data not shown). Five days and 48 hours after optic and sciatic nerve transections, respectively, mice were euthanized and fresh nerve tissue harvested for analysis. Intact NFL levels did not differ between WT and hCAST mice in uninjured optic (p=0.21) and sciatic nerves (p=0.60) (Figure 3A and B). Significant loss of intact NFL was accompanied by the generation of the ~22 and ~40 kDa NFL fragments after optic and sciatic nerve transections in WT mice. However, hCAST expression reduced NFL proteolysis in transected nerves. For transected optic nerves, intact NFL was preserved (p=0.007) and levels of both the ~22 (p<0.0001) and ~40 kDa (p<0.0001) NFL fragments were reduced in hCAST mice, as compared to WT controls. Transected sciatic nerves in hCAST mice exhibited preservation of intact NFL (p=0.0008) and reduction in the generation of both the ~22 (p<0.0001) and ~40 kDa (p<0.0001) NFL fragments, as compared to injured WT nerves.

Figure 3. In vivo neurofilament proteolysis in wild-type and transgenic mice.

(A) Representative western blots of homogenates or supernatants of transected (cut) and contralateral uninjured optic and sciatic nerves from wild-type (WT) and transgenic (TG) mice using antiserum against neurofilament light (NFL). (B) Quantification of intact NFL and the ~40 and ~22 kDa proteolytic fragments. n=6–7 mice per group (optic nerve) and n=7–9 per group (sciatic nerve). (C) Representative western blot of supernatants of transected and contralateral uninjured sciatic nerves from WT and TG mice using an antibody targeting neurofilament heavy (NFH). NFH appears as a doublet, due to differential phosphorylation (Park et al., 2007). (D) Quantification of intact NFH doublet. Error bars represent SD. *p<0.01 **p<0.001. Human calpastatin blocked loss of full-length NFL and NFH, as well as the generation of the ~40 and ~22 kDa NFL fragments.

Similarly, 48 hours after sciatic nerve transection, there was a significant loss of intact neurofilament heavy (NFH) in WT mice (p=0.0001; Figure 3C and D), which was reduced by hCAST expression (p=0.002; WT injured versus hCAST injured). Intact NFH levels in uninjured nerves were no different in WT versus hCAST mice (p=0.29).

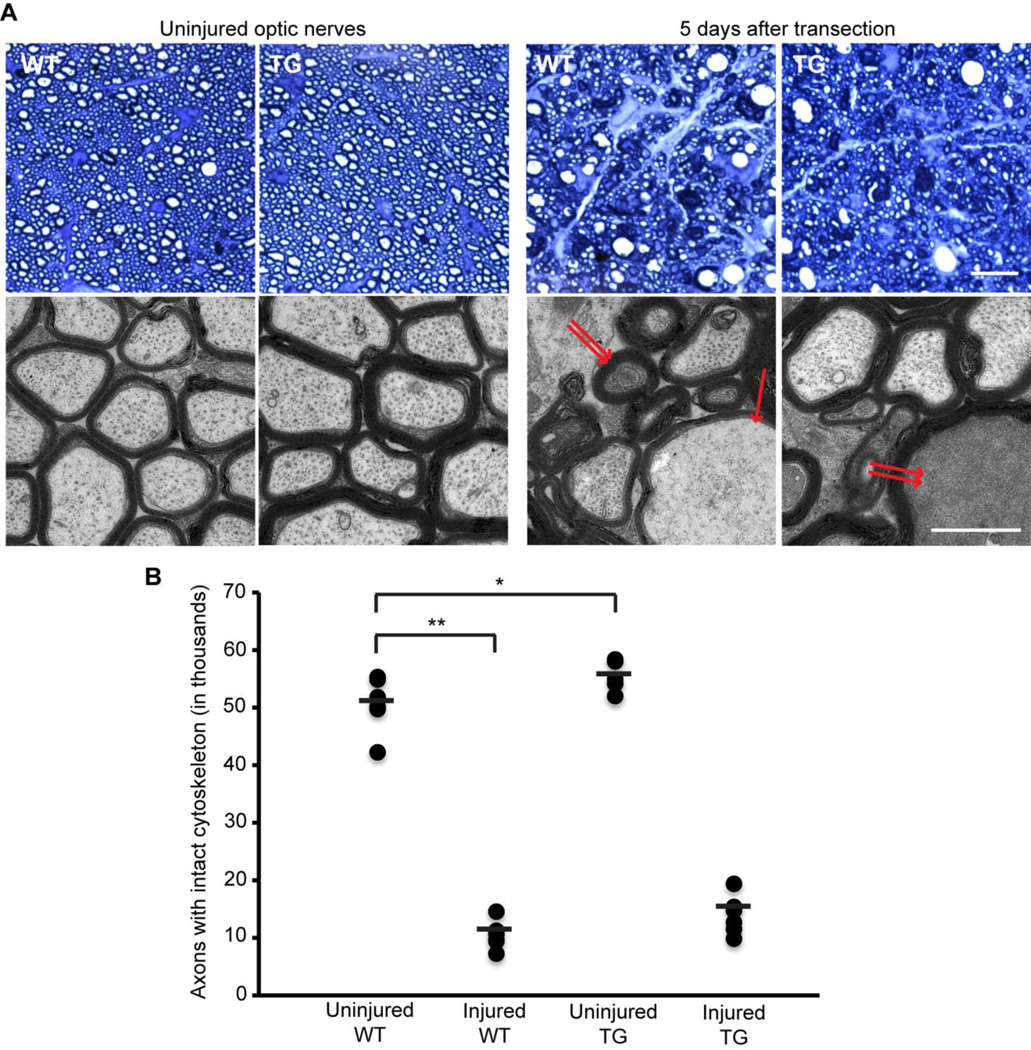

Morphological effects of human calpastatin expression on axonal cytoskeleton

Five days after unilateral optic nerve transection, anesthetized animals were euthanized by perfusion fixation for ultrastructural analysis (Figure 4). Uninjured optic nerves from WT and hCAST mice contained a total of 50,775±4,345 and 54,912±2,797 myelinated axons with preserved cytoskeleton, respectively (p=0.011). After transection, 10,556±2,229 axons with preserved cytoskeleton remained in WT mice (p<0.0001 compared to contralateral uninjured side), and 13,919±3,369 in hCAST mice (p=0.03 compared to injured nerves of WT littermates). In both WT and hCAST mice, the majority of degenerating axons were diffusely filled with electron-dense material, consistent with “dark degeneration” (Bignami et al., 1981; Marques et al., 2003; Narciso et al., 2001). Because the integrity of the axonal cytoskeleton could not be reliably assessed in axons undergoing “dark degeneration” (Marques et al., 2003), they were not scored as intact. A smaller population of degenerating axons, whose axoplasm was not obscured by “dark degeneration,” was undergoing granular disintegration of the axonal cytoskeleton (GDC).

Figure 4. Axonal cytoskeleton 5 days after optic nerve transection in wild-type and transgenic mice.

(A) Representative light and electron microscopic images of optic nerves from wild-type (WT) and transgenic (TG) mice. An optic nerve axon undergoing granular disintegration of the axonal cytoskeleton is marked by single arrow, while two of the axons undergoing “dark degeneration” are marked by double arrows. Scale bar=10 µm (light microscopy), 1 µm (electron microscopy). (B) Quantification of axons with intact cytoskeleton. n=6–7 mice per group. Each circle represents an individual nerve, while horizontal bars represent means. *p<0.017 **p<0.0001. Human calpastatin did not provide statistically significant morphological protection to transected optic nerve axons.

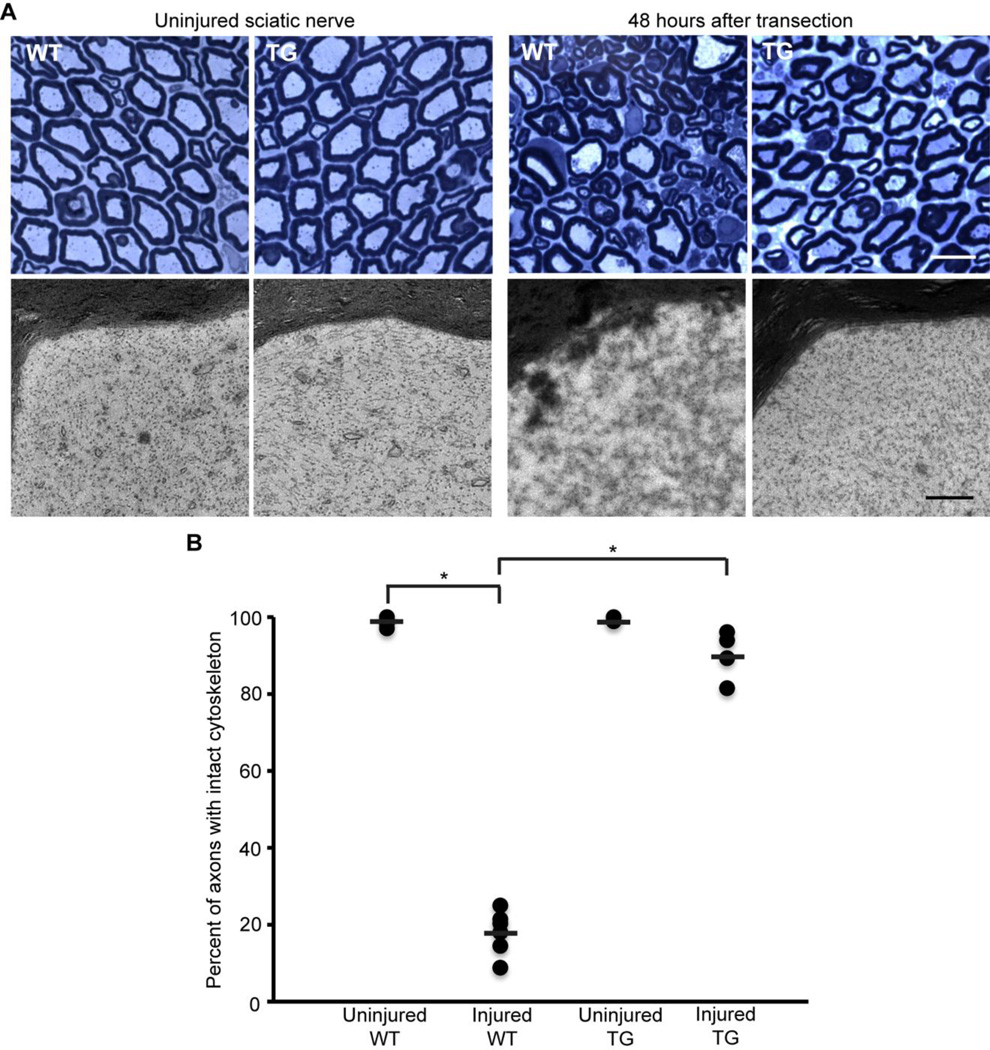

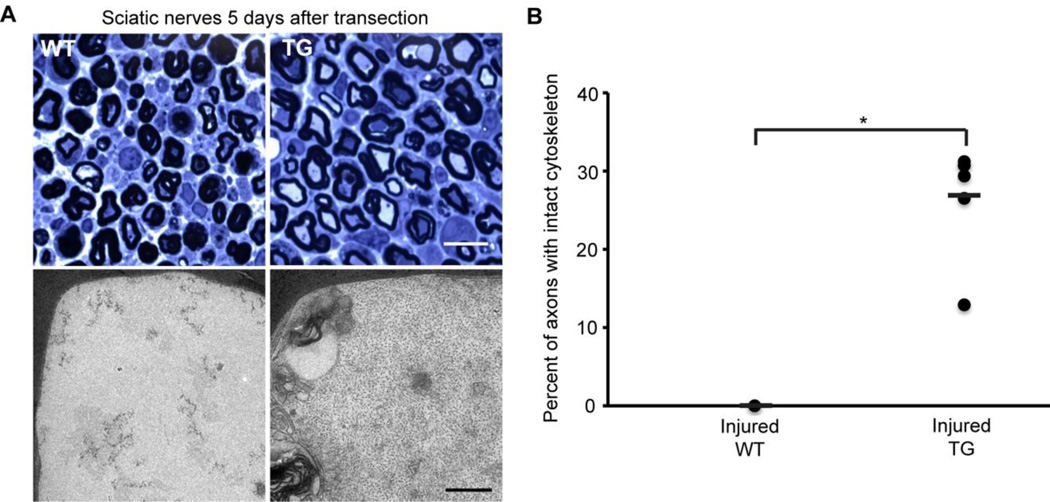

Sciatic nerves were initially examined 48 hours after transection. Myelinated axons were scored for the presence or absence of intact cytoskeleton. In uninjured nerves, ~99% of axons in WT and hCAST mice had preserved cytoskeleton (p=0.84 comparing uninjured WT to uninjured hCAST nerves; Figure 5). However, 48 hours after nerve transection in WT mice, only 18.3±5.3% of the axons had cytoskeletal preservation (p<0.0001 compared to uninjured contralateral nerves). Overexpression of calpastatin resulted in robust protection of transected axons, with 90.2±6.5% of axons having cytoskeletal preservation (p<0.0001 compared to injured WT). To better establish the duration of protection in the PNS, we examined sciatic nerves in WT and hCAST mice 5 days after transection (Figure 6). The uninjured contralateral nerves were normal appearing (data not shown). In seven injured WT nerves, not a single axon (0.0±0.0%) was scored as having preserved cytoskeletal structure. However, in hCAST mice, 26.9±7.1% of axons had preserved cytoskeleton (p=0.0002 compared to injured WT).

Figure 5. Axonal cytoskeleton 48 hours after sciatic nerve transection in wild-type and transgenic mice.

(A) Representative light and electron microscopic images of sciatic nerves from wild-type (WT) and transgenic (TG) mice. Scale bar=10 µm (light microscopy), 0.5 µm (electron microscopy). (B) Percentage of axons scored as intact 48 hours after sciatic nerve transection (n=7 WT and 4 TG). Each circle represents an individual nerve, while horizontal bars represent means. *p<0.0001. Protection of the axonal cytoskeleton in sciatic nerves of TG mice was nearly complete at 48 hours post-transection.

Figure 6. Axonal cytoskeleton 5 days after sciatic nerve transection in wild-type and transgenic mice.

(A) Representative light and electron microscopic images of sciatic nerves from wild-type (WT) and transgenic (TG) mice. Scale bar=10 µm (light microscopy), 0.5 µm (electron microscopy). (B) Percentage of axons scored as intact 5 days after sciatic nerve transection (n=7 WT and 6 TG). Each circle represents an individual nerve, while horizontal bars represent means. *p≤0.0002. Morphological protection of sciatic nerves was statistically significant 5 days post-transection with human calpastatin expression.

Effect of human calpastatin expression on neuromuscular junctions after sciatic nerve transection

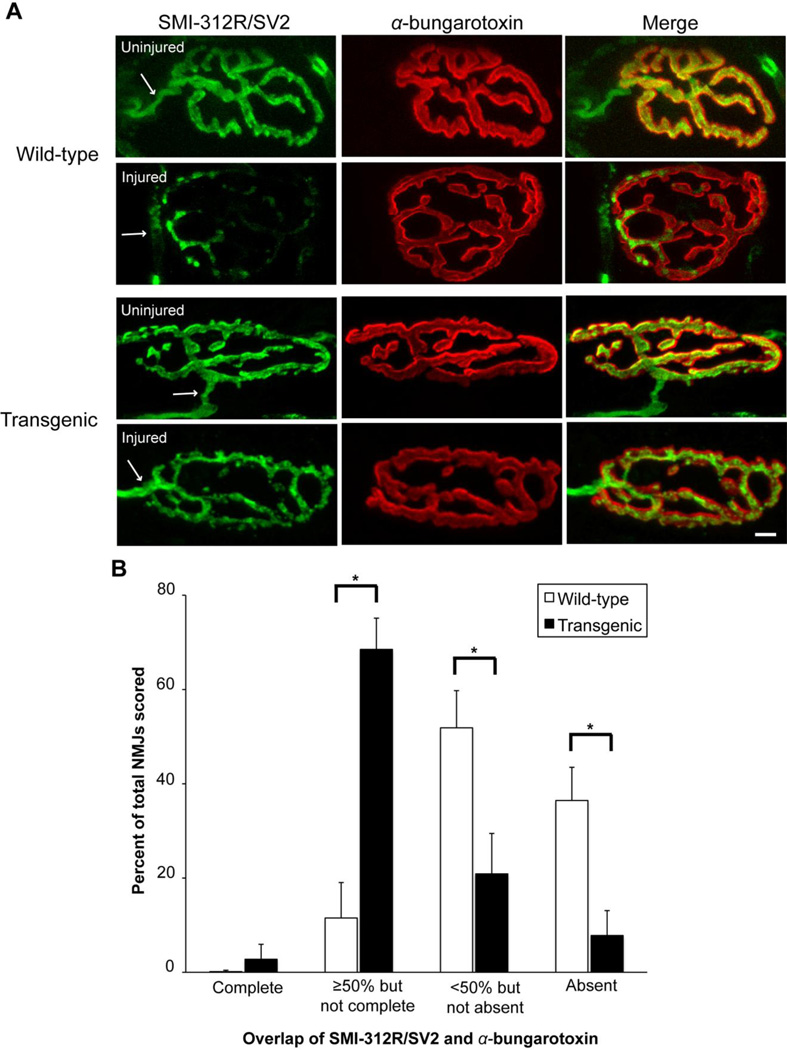

Morphological protection of the preterminal axon, terminal arborization, and NMJ with pharmacologic calpain inhibitors was demonstrated in an ex vivo model of motor nerve terminal injury caused by α-latrotoxin or activated complement (McGonigal et al., 2010; O'Hanlon et al., 2003). To the best of our knowledge, in vivo protection of NMJs with calpain inhibition has not been reported. During Wallerian degeneration in vivo, the degeneration of the presynaptic terminal is one of the earliest pathology seen after nerve transection (Miledi and Slater, 1970). Therefore, we examined NMJs in WT mice between 15 and 30 hours after sciatic nerve transection, and confirmed that over 90% of NMJs have degenerated 24 hours after sciatic nerve transection (data not shown). Based on this time course, we euthanized a cohort of WT and hCAST mice 18 hours after unilateral nerve transection, followed by removal of the extensor digitorum longus muscle for immunostaining of the NMJs using a neurofilament marker (SMI-312R; green), synaptic vesicle marker (SV2; green), and rhodamine-conjugated α-bungarotoxin (red). In muscle innervated by nontransected nerves of WT and hCAST mice, the preterminal axons appeared normal, and essentially all NMJs had complete innervation, as defined by the overlap of SMI-312R/SV2 and α-bungarotoxin labeling (Figure 7A). Eighteen hours after transection, the preterminal axon appeared fragmented in WT mice, which was ameliorated by hCAST expression. After nerve transection, 0.1±0.3% and 2.8±3.2% of the NMJs in WT and hCAST mice, respectively, remained completely innervated (p=0.47; Figure 7B). However, 11.5±7.9% of NMJs in WT mice had ≥50% but not complete innervation, compared to 68.5±8.6% of NMJs in the hCAST mice (p<0.0001), indicating partial NMJ protection with hCAST expression.

Figure 7. Denervation of neuromuscular junctions after sciatic nerve transection in wild-type and transgenic mice.

(A) Representative images of neuromuscular junctions (NMJs) 18 hours after transection in wild-type (WT) and transgenic (TG) mice. SMI-312R/SV2 antibodies (green) label preterminal axons and the presynaptic compartment, while α-bungarotoxin (red) labels the postsynaptic membrane. Arrows mark the preterminal axon. Scale bar=10 µm. (B) NMJs were classified into one of 4 groups on the basis of SMI-312R/SV2 coverage of α-bungarotoxin labeling: (1) complete innervation, (2) ≥50% innervation but not complete, (3) <50% innervation, but not absent, (4) absent innervation. The Y axis represents the mean percentage of NMJs classified in each group (n=10 WT and 7 TG). Error bars represent SD. Data from the uninjured side is not shown. *p<0.0001. Human CAST expression preserved NMJ innervation after sciatic nerve transection.

To better quantify calpain-mediated NMJ protection after nerve transection, we also calculated the ratio of preserved pre-synaptic area to post-synaptic area. For this assessment, we excluded from analysis any NMJ that was completely devoid of SMI-312R/SV2 labeling (36.5±7.0% and 7.8±5.3% of NMJs in WT and hCAST mice, respectively). Despite this, after sciatic nerve transection, a significantly higher percentage of the postsynaptic terminal remained innervated in hCAST mice (45.4±5.2% versus 8.1±4.1% in WT mice; p<0.0001), confirming morphological protection of NMJs with hCAST expression.

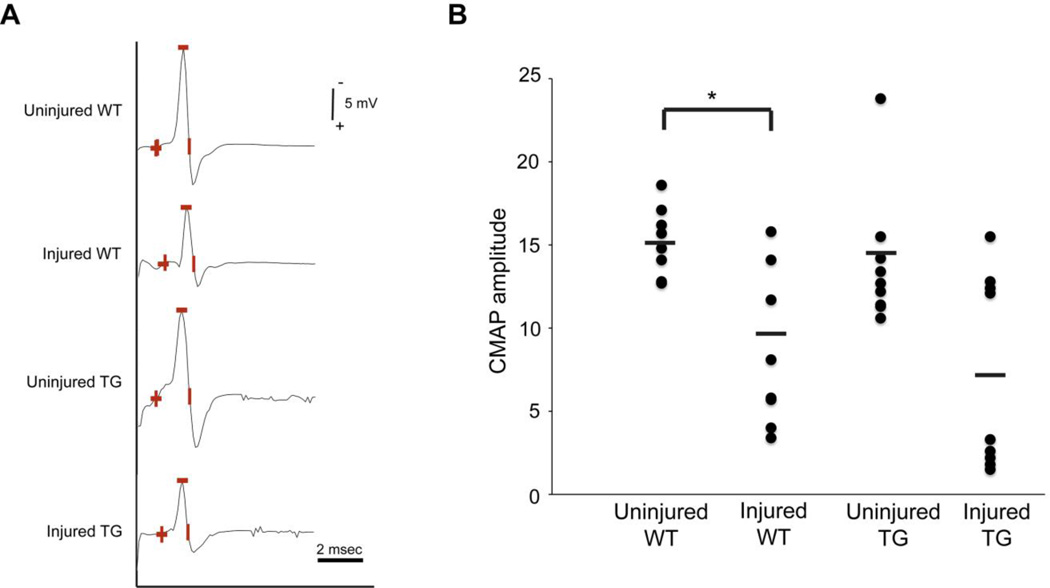

To determine if calpain inhibition preserves peripheral nerve electrical function, we recorded the compound muscle action potential (CMAP) after nerve transection. Evidence supports that early impairment of CMAP represents synaptic dysfunction rather than failure of action potential conduction through the distal nerve trunk (Miledi and Slater, 1970; Okamoto and Riker, 1969). In our initial experiments in WT mice, we found that CMAP decay started at approximately ten hours and was nearly complete by 16 hours, consistent with the work of others (Moldovan et al., 2009). Therefore, we examined CMAP preservation 14 hours after transection. CMAP amplitudes did not differ between the uninjured nerves in the WT (15.2±1.8 mV) and hCAST mice (13.9±4.0 mV; p=0.54; Figure 8). Compared to the uninjured contralateral side, CMAP amplitude decreased 35±32% in transected nerves in WT mice (p=0.009). However, CMAP amplitudes did not differ between the injured nerves in WT (9.9±5.0 mV) and hCAST mice (7.1±5.9 mV; p=0.51).

Figure 8. Motor nerve responses after sciatic nerve transection in wild-type and transgenic mice.

(A) Representative motor nerve responses from stimulation of wild-type (WT) and transgenic (TG) sciatic nerves 14 hours after transection and their uninjured contralateral controls. Amplitude was measured from baseline to peak (marked by the minus sign). (B) Compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitudes are plotted for 10 WT and 9 TG mice. Each circle represents an individual nerve, while horizontal bars represent means. *p<0.01. Human CAST expression does not improve motor nerve responses of transected sciatic nerves.

DISCUSSION

In summary, these findings strongly support that calpains are causally responsible for axonal cytoskeleton disintegration and synaptic degeneration during Wallerian degeneration. The evidence, in total, supports a similar role of calpains in mediating GDC in the CNS and PNS. Calpain inhibition was not sufficient to preserve electrophysiological function, however. Therefore, calpain inhibition is likely necessary, but not sufficient, to preserve injured axons and their synapses.

Calpains are causally responsible for axonal and synaptic degeneration during Wallerian degeneration

Two in vivo studies examining the role of calpains in axonal degeneration provided inconclusive results. Pretreatment with intraperitoneally administered calpain inhibitor leupeptin, which was continued throughout the survival period, did not reduce NFL degradation 72 hours post-sciatic nerve transection (Glass et al., 2002). However, as leupeptin has poor cellular permeability (Pietsch et al., 2010), it is possible that intra-axonal concentrations of leupeptin were insufficient to inhibit calpains. In another study, topical application of a calpain inhibitor (Mu-F-HF-FMK) directly to the optic nerve crush site in opossums was marginally protective (Couto, et al., 2004). Ninety-six hours post-injury, the drug-treated group showed a statistically significant, but small, increase in intact axons (76±3.7% versus 67±4.2% nontreated injured). The inhibitor used also inhibits cathepsin L (product data sheet from Kamiya Biomedical), which is likely important for autophagy (Kaasik et al., 2005). As autophagy has been implicated in axonal degeneration (Beirowski et al., 2010; Knöferle et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2007), the use of an inhibitor of both calpains and cathepsin L, which had a modest protective effect, limits experimental interpretation.

Our study has several strengths, which allow us to conclude that intra-axonal calpain activity is casually responsible for axonal degeneration in vivo. First, we identified and measured an axon-specific calpain reaction product (calpain-cleaved NFL) in nerves to establish the presence and time course of pathologic calpain activity during Wallerian degeneration. Previously, in vivo calpain activity had only been detected within the first few hours after nerve transection (Glass et al., 2002). Glass and colleagues (2002) measured calpain activity by Western blotting nerve homogenates with Ab38, which recognizes a calpain-cleaved αII-spectrin fragment. Their inability to detect calpain activity at later time points is possibly due to the low baseline amount of αII-spectrin in sciatic nerves or the instability of the fragment in the setting of robust and prolonged calpain activity. Another strength of our study is that we relied on overexpression of calpastatin, which only inhibits calpains and no other proteases (Goll et al., 2003). An alternative and complementary approach would be inducible, cell-specific deletion of various calpain isoforms, particularly calpain 1, calpain 2 or their common regulatory subunit. Finally, immunohistochemistry of sciatic nerves revealed calpastatin only within axons, suggesting that the calpain inhibitory effect was limited to the axonal compartment. In sciatic nerves, the neuronal component, which immunolabels with class III β-tubulin, exclusively consists of axons.

We extended our understanding of the role of calpains in Wallerian degeneration by examining PNS synapses. Calpastatin overexpression reduced denervation of NMJs after nerve transection. It is likely that localized calpain activity within the NMJ presynaptic terminal is directly responsible for denervation. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that denervation is a “byproduct” of axonal degeneration, but this is less likely given that NMJ degeneration is detected earlier than that of sciatic nerve axons. Nevertheless, our data is consistent with published results demonstrating morphological protection of NMJs by pharmacologic calpain inhibitors in an ex vivo model of anti-ganglioside antibody-mediated motor nerve terminal injury (O'Hanlon et al., 2003) and in vitro model of ischemia (Talbot et al., 2012). The importance of calpains in these different injury models suggests that calpain-mediated degeneration is an important mechanism of synaptic pathology in many diseases.

Reduction in axonal and synaptic degeneration after axonal transection has also been demonstrated in slow Wallerian degeneration (Wlds) mice (Coleman, 2005; Mack et al., 2001; Vargas and Barres, 2007) and Sarm1 null mice (Osterloh et al., 2012). It is not known if further protection is obtained with calpastatin overexpression in these two mice lines, or if calpains act in the same pathway or in parallel to the Wlds or Sarm1 proteins.

Calpains are responsible for neurofilament degradation during granular disintegration of the axonal cytoskeleton

Our evidence demonstrates that calpains are responsible for the in vivo proteolysis of neurofilaments in Wallerian degeneration, which corroborates in vitro studies (Finn et al., 2000; Zhai et al., 2003). In our study, NFL proteolysis and/or NFH loss were significantly reduced with hCAST expression after either optic or sciatic nerve transection. It is not clear if neurofilament preservation, per se, directly contributes to axonal protection. It may be that neurofilament degradation, irrespective of proximate cause, may act as a trigger for other downstream degenerative events.

While the level of NFL protection was similar in both nerves, Wallerian degeneration was delayed in optic nerves. Axonal degeneration is usually considered slower in the CNS, but this has not been systematically examined nor is this universally true (George and Griffin, 1994). It is not clear why some nerves undergo axonal degeneration earlier than others and this disparity may reflect differences intrinsic to CNS and PNS neurons, or may be due to extraneuronal factors. For example, different cell types, oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells, myelinate axons in the CNS and PNS, respectively.

We also examined axonal morphology after injury in both sciatic and optic nerves. Ultrastructural preservation of neurofilaments was evident after sciatic nerve transection in hCAST mice. In contrast, we did not observe significant morphological protection in transected optic nerves in hCAST mice. Scoring of the axonal cytoskeleton in optic nerves could not be reliably performed as the majority of degenerating axons in both WT and hCAST animals were undergoing “dark degeneration,” a finding previously documented in transected optic nerves of WT rats (Marques et al., 2003). In axons undergoing “dark degeneration,” the cytoskeletal structure of the axon was obscured. Using immunoelectron microscopy, axons undergoing “dark degeneration,” but not those undergoing GDC, labeled for neurofilaments (Marques et al., 2003), which is consistent with our belief that scoring the axonal cytoskeleton may be unreliable in axons undergoing “dark degeneration.”

While we demonstrated similar biochemical preservation of neurofilaments in the CNS and PNS, and robust morphological protection in the PNS with hCAST expression, “dark degeneration” likely prevented us from determining if similar morphologic protection was observed in the CNS. It is likely that “dark degeneration” obscures the morphologic protection with hCAST expression in transected optic nerve axons. Thus, while we believe that calpains mediate GDC in both the CNS and PNS, this conclusion, for optic nerve axons, is largely supported by our data demonstrating robust protection of NFL proteolysis by Western blot. Neither the functional significance nor the axonal constituents of “dark degeneration” is known. Besides calpains, other parallel mechanisms may contribute to axonal degeneration, particularly in “dark degenerating” axons in the CNS.

Calpain inhibition protects distal axonal and synaptic structure, but not electrophysiologic function

We were able to demonstrate robust morphological protection of the preterminal axons and NMJs by hCAST expression. Similar effects were seen with pharmacologic calpain inhibitors in an ex vivo model of motor nerve terminal injury caused by α-latrotoxin or activated complement (McGonigal et al., 2010; O’Hanlon et al., 2003). Both α-latrotoxin and activated complement likely form non-selective pores within the target membrane allowing dysregulated passage of Ca2+, other ions and small molecules. Calpain inhibitors robustly protected the preterminal axon and terminal arborization, as visualized by neurofilament immunolabeling, as well as prevented the loss of “cytoskeletal bundles” in the presynaptic NMJ (McGonigal et al., 2010; O’Hanlon et al., 2003).

Despite robust morphological protection by hCAST expression in our in vivo model, electrophysiological function was not apparently preserved (CMAP amplitudes of 9.9±5.0 and 7.1±5.9 mV in the WT and TG injured groups, respectively; p=0.51). In our initial a priori statistical analysis, we did not determine if CMAP amplitude decreased significantly after injury in hCAST mice. Therefore, to address whether the high variability, particularly within the injured groups, masked an injury effect in hCAST mice, we performed a post hoc analysis comparing CMAP amplitudes of uninjured versus injured hCAST groups, and detected a statistically significant difference (p=0.006). Nonetheless, albeit unlikely, this high variability could mask a small protective effect by hCAST at our 14-hour post-injury time point.

The reason for the lack of electrophysiological protection is not clear. Other investigators identified a similar divergence between structural and electrophysiologic effects of calpain inhibition on injured axons. In an ex vivo model of nodal injury caused by activated complement, the calpain inhibitor AK295 preserved immunoreactivity of the Na+ channel Nav1.6, ankyrin G, Caspr, and neurofascin at the nodes and paranodes of intramuscular nerve bundles, but did not protect perineural currents (McGonigal et al., 2010). The loss of recordable perineural currents indicates a disruption of the ability of the node and motor nerve terminal to generate Na+ and K+ currents, respectively. The investigators also measured compound action potential (CAP) in experimentally desheathed phrenic nerve trunks exposed to activated complement. Despite protection of nodal structure by AK295, injury-induced decrement of CAP amplitude was not ameliorated. The authors suggested that in their ex vivo injury models, the critical factor in mediating failure of axonal conduction was the failure of the disrupted axolemmal membrane to maintain ionic homeostasis (McGonigal et al., 2010). Similarly, pharmacologic calpain inhibitors protected against neurofilament and spectrin breakdown in optic nerves exposed to ex vivo anoxia or oxygen-glucose deprivation in the absence of electrophysiological preservation (Jiang and Stys, 2000; Stys and Jiang, 2002). As removing extracellular Ca2+ was completely protective of CAP after injury, other Ca2+–dependent pathways, such as phospholipases, phosphatases, or kinases, were suggested as potential factors in mediating electrophysiological deterioration.

Improvement of electrophysiological outcome measures with pharmacologic calpain inhibitors have been reported in animal models of traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer’s disease, and taxol-induced sensory neuropathy (Ai et al., 2007; Trinchese et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2004). Given the complexity of these injury models and the systemic administration of the inhibitors, it is unlikely that the protective effects can be attributed solely to inhibition of intra-axonal calpains. In these animal models, calpain activity in the neuronal somata or dendrites, glial cells or other structures may be the key pathologic mechanism. Nonetheless, the studies support the therapeutic potential of pharmacologic calpain inhibitors in human diseases where early axonal and synaptic pathology may be paramount.

Conclusions

Intra-axonal calpain activity is at least in part causally responsible for granular disintegration of the axonal cytoskeleton and target denervation in Wallerian degeneration. However, calpain inhibition does not provide concomitant electrophysiological protection. As axonal pathology may contribute to morbidity in CNS and PNS trauma, cerebral ischemia, neurodegenerative diseases, and peripheral neuropathies (Blumbergs et al., 1995; Coleman, 2005; Medana and Esiri, 2003; Saxena and Caroni, 2007; Shy et al., 2002), inhibition of intra-axonal calpains is likely a necessary component of any effective therapeutic strategy for a wide spectrum of human diseases.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Calpastatin overexpressing mice were used to study axonal degeneration mechanisms.

Neurofilament proteolysis during Wallerian degeneration is mediated by calpains.

Calpains contribute to granular disintegration of the axonal cytoskeleton.

Calpastatin preserves innervation of neuromuscular junctions after nerve transection.

Intra-axonal calpain inhibition does not provide electrophysiological protection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Steven S. Scherer (University of Pennsylvania) for his guidance in many aspects of this project, Glenn C. Telling (Colorado State University) who created the transgenic mice, and Dewight Williams (University of Pennsylvania) for assistance with electron microscopy. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants K08NS055880 (MM), K08NS065157 (TAF), P30AR050950 (TAF, S. Scherer, Penn Center for Musculoskeletal Disorders), F31NS071804 (KMS), and P01NS058484 (KES), Shriners Pediatric Research Center Seed funding (TAF), and Kentucky Spinal Cord and Head Injury Research Trust (KSCHIRT) 6–12 (KES).

The funding sources had no involvement in the conduct of the research or the preparation of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- CAP

compound action potential

- CAST

calpastatin

- CMAP

compound muscle action potential

- CNS

central nervous system

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GDC

granular disintegration of the axonal cytoskeleton

- hCAST

human calpastatin

- IP

intraperitoneal

- NFH

neurofilament heavy

- NFL

neurofilament light

- NMJ

neuromuscular junction

- PB

phosphate buffer

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PNS

peripheral nervous system

- Prp

prion protein

- TG

transgenic

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Ai J, Liu E, Wang J, Chen Y, Yu J, Baker AJ. Calpain inhibitor MDL-28170 reduces the functional and structural deterioration of corpus callosum following fluid percussion injury. J. Neurotrauma. 2007;24:960–978. doi: 10.1089/neu.2006.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauder AR, Ferguson TA. Reproducible mouse sciatic nerve crush and subsequent assessment of regeneration by whole mount muscle analysis. J. Vis. Exp. 2012;60:e3606. doi: 10.3791/3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beirowski B, Nógrádi A, Babetto E, Garcia-Alias G, Coleman MP. Mechanisms of axonal spheroid formation in central nervous system Wallerian degeneration. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2010;69:455–472. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181da84db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bignami A, Dahl D, Nguyen BT, Crosby CJ. The fate of axonal debris in Wallerian degeneration of rat optic and sciatic nerves. Electron microscopy and immunofluorescence studies with neurofilament antisera. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 1981;40:537–550. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198109000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumbergs PC, Scott G, Manavis J, Wainwright H, Simpson DA, McLean AJ. Topography of axonal injury as defined by amyloid precursor protein and the sector scoring method in mild and severe closed head injury. J. Neurotrauma. 1995;12:565–572. doi: 10.1089/neu.1995.12.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman M. Axon degeneration mechanisms: commonality amid diversity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005;6:889–898. doi: 10.1038/nrn1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couto LA, Narciso MS, Hokoç JN, Martinez AMB. Calpain inhibitor 2 prevents axonal degeneration of opossum optic nerve fibers. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004;77:410–419. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui Q, Yip HK, Zhao RCH, So KF, Harvey AR. Intraocular elevation of cyclic AMP potentiates ciliary neurotrophic factor-induced regeneration of adult rat retinal ganglion cell axons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2003;22:49–61. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(02)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn JT, Weil M, Archer F, Siman R, Srinivasan A, Raff MC. Evidence that Wallerian degeneration and localized axon degeneration induced by local neurotrophin deprivation do not involve caspases. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:1333–1341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01333.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George EB, Glass JD, Griffin JW. Axotomy-induced axonal degeneration is mediated by calcium influx through ion-specific channels. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:6445–6452. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06445.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George R, Griffin JW. Delayed macrophage responses and myelin clearance during Wallerian degeneration in the central nervous system: the dorsal radiculotomy model. Exp. Neurol. 1994;129:225–236. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JD. Wallerian degeneration as a window to peripheral neuropathy. J. Neurol. Sci. 2004;220:123–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass JD, Culver DG, Levey AI, Nash NR. Very early activation of m-calpain in peripheral nerve during Wallerian degeneration. J. Neurol. Sci. 2002;196:9–20. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00013-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goll DE, Thompson VF, Li H, Wei W, Cong J. The calpain system. Physiol. Rev. 2003;83:731–801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen HJG, Bendtsen TF, Korbo L, Marcussen N, Møller A, Nielsen K, et al. Some new, simple and efficient stereological methods and their use in pathological research and diagnosis. APMIS. 1988;96:379–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1988.tb05320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Q, Stys PK. Calpain inhibitors confer biochemical, but not electrophysiological, protection against anoxia in rat optic nerves. J. Neurochem. 2000;74:2101–2107. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0742101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaasik A, Rikk T, Piirsoo A, Zharkovsky T, Zharkovsky A. Up-regulation of lysosomal cathepsin L and autophagy during neuronal death induced by reduced serum and potassium. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;22:1023–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knöferle J, Koch JC, Ostendorf T, Michel U, Planchamp V, Vutova P, et al. Mechanisms of acute axonal degeneration in the optic nerve in vivo . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:6064–6069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909794107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwong JMK, Quan A, Kyung H, Piri N, Caprioli J. Quantitative analysis of retinal ganglion cell survival with Rbpms immunolabeling in animal models of optic neuropathies. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011;52:9694–9702. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma M, Matthews BT, Lampe JW, Meaney DF, Shofer FS, Neumar RW. Immediate short-duration hypothermia provides long-term protection in an in vivo model of traumatic axonal injury. Exp. Neurol. 2009;215:119–127. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack TGA, Reiner M, Beirowski B, Mi W, Emanuelli M, Wagner D, Thomson D, et al. Wallerian degeneration of injured axons and synapses is delayed by a Ube4b/Nmnat chimeric gene. Nat. Neurosci. 2001;4:1199–1206. doi: 10.1038/nn770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques SA, Taffarel M, Martinez AMB. Participation of neurofilament proteins in axonal dark degeneration of rat's optic nerves. Brain Res. 2003;969:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03834-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonigal R, Rowan EG, Greenshields KN, Halstead SK, Humphreys PD, Rother RP, et al. Anti-GD1a antibodies activate complement and calpain to injure distal motor nodes of Ranvier in mice. Brain. 2010;133:1944–1960. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medana IM, Esiri MM. Axonal damage: a key predictor of outcome in human CNS diseases. Brain. 2003;126:515–530. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miledi R, Slater CR. On the degeneration of rat neuromuscular junctions after nerve section. J. Physiol. 1970;207:507–528. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1970.sp009076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moldovan M, Alvarez S, Krarup C. Motor axon excitability during Wallerian degeneration. Brain. 2009;132:511–523. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narciso MS, Hokoç JN, Martinez AMB. Watery and dark axons in Wallerian degeneration of the opossum's optic nerve: different patterns of cytoskeletal breakdown? An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2001;73:231–243. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652001000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hanlon GM, Humphreys PD, Goldman RS, Halstead SK, Bullens RWM, Plomp JJ, et al. Calpain inhibitors protect against axonal degeneration in a model of anti-ganglioside antibody-mediated motor nerve terminal injury. Brain. 2003;126:2497–2509. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada E, Mizuhira V, Nakamura H. Abnormalities of the sciatic nerves of dystrophic mice, with reference to nerve counts and mean area of axons. Bull. Tokyo Med. Dent. Univ. 1975;22:25–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Riker WF., Jr Motor nerve terminals as the site of initial functional changes after denervation. J. Gen. Physiol. 1969;53:70–80. doi: 10.1085/jgp.53.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterloh JM, Yang J, Rooney TM, Fox AN, Adalbert R, Powell EH, et al. dSarm/Sarm1 is required for activation of an injury-induced axon death pathway. Science. 2012;337:481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1223899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osuchowski MF, Teener J, Remick D. Noninvasive model of sciatic nerve conduction in healthy and septic mice: reliability and normative data. Muscle Nerve. 2009;40:610–616. doi: 10.1002/mus.21284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park E, Liu E, Shek M, Park A, Baker AJ. Heavy neurofilament accumulation and α-spectrin degradation accompany cerebellar white matter functional deficits following forebrain fluid percussion injury. Exp. Neurol. 2007;204:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2006.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietsch M, Chua KCH, Abell AD. Calpains: attractive targets for the development of synthetic inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2010;10:270–293. doi: 10.2174/156802610790725489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saatman KE, Murai H, Bartus RT, Smith DH, Hayward NJ, Perri BR, et al. Calpain inhibitor AK295 attentuates motor and cognitive deficits following experimental brain injury in the rat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:3428–3433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saatman KE, Creed J, Raghupathi R. Calpain as a therapeutic target in traumatic brain injury. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:31–42. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Caroni P. Mechanisms of axon degeneration: from development to disease. Prog. Neurobiol. 2007;83:174–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch KM, von Reyn CR, Bian J, Telling GC, Meaney DF, Saatman KE. Brain injury-induced proteolysis is reduced in a novel calpastatin overexpressing transgenic mouse. J. Neurochem. in press doi: 10.1111/jnc.12144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shy ME, Garbern JY, Kamholz J. Hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies: a biological perspective. Lancet Neurol. 2002;1:110–118. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(02)00042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stys PK, Jiang Q. Calpain-dependent neurofilament breakdown in anoxic and ischemic rat central axons. Neurosci. Lett. 2002;328:150–154. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00469-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talbot JD, David G, Barrett EF, Barrett JN. Calcium dependence of damage to mouse motor nerve terminals following oxygen/glucose deprivation. Exp. Neurol. 2012;234:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinchese F, Fa' M, Liu S, Zhang H, Hidalgo A, Schmidt SD, et al. Inhibition of calpains improves memory and synaptic transmission in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:2796–2807. doi: 10.1172/JCI34254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas ME, Barres BA. Why is Wallerian degeneration in the CNS so slow? Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;30:153–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller A. Experiments on the section of the glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves of the frog, and observations of the alterations produced thereby in the structure of their primitive fibres. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. London. 1850;140:423–429. [Google Scholar]

- Wang JT, Medress ZA, Barres BA. Axon degeneration: molecular mechanisms of a self-destruction pathway. J. Cell Biol. 2012;196:7–18. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M-S, Wu Y, Culver DG, Glass JD. Pathogenesis of axonal degeneration: parallels between Wallerian degeneration and vincristine neuropathy. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2000;59:599–606. doi: 10.1093/jnen/59.7.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang MS, Davis AA, Culver DG, Wang Q, Powers JC, Glass JD. Calpain inhibition protects against taxol-induced sensory neuropathy. Brain. 2004;127:671–679. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitmore AV, Lindsten T, Raff MC, Thompson CB. The proapoptotic proteins Bax and Bak are not involved in Wallerian degeneration. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:260–261. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Fukui K, Koike T, Zheng X. Induction of autophagy in neurite degeneration of mouse superior cervical ganglion neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007;26:2979–2988. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Q, Wang J, Kim A, Liu Q, Watts R, Hoopfer E, et al. Involvement of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in the early stages of wallerian degeneration. Neuron. 2003;39:217–225. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00429-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman U-JP, Schlaepfer WW. Characterization of a brain calcium-activated protease that degrades neurofilament proteins. Biochemistry. 1982;21:3977–3983. doi: 10.1021/bi00260a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]