Summary

Objectives

to describe yoga practice and health characteristics of individuals who practice yoga, and to explore their beliefs regarding the effects of their yoga practice on their health.

Design

a cross-sectional design with anonymous online surveys

Setting

4307 randomly selected individuals from 15 US Iyengar yoga studios (n = 18,160), representing 41 states; 1087 individuals responded, with 1045 (24.3%) surveys completed.

Outcome Measures

Freiberg Mindfulness Inventory, Mental Health Continuum (subjective well-being), Multi-factor Screener (diet), PROMIS sleep disturbance, fatigue, and social support, International Physical Activity Questionnaire.

Results

Age: 19 to 87 years (M = 51.7 ± 11.7), 84.2% female, 89.2% white, 87.4% well educated (≥ bachelor’s degree). Mean years of yoga practice = 11.4 (± 7.5). BMI = 12.1–49.4 (M = 23.1 ± 3.9). Levels of obesity (4.9%), smoking (2%), and fruit and vegetable consumption (M = 6.1 ± 1.1) were favorable compared to national norms. 60% reported at least one chronic/serious health condition, yet most reported very good (46.3%) or excellent (38.8%) general health. Despite high levels of depression (24.8 %), nearly all were moderately mentally healthy (55.2%) or flourishing (43.8%). Participants agreed yoga improved: energy (84.5%), happiness (86.5%), social relationships (67%), sleep (68.5%), and weight (57.3%), and beliefs did not differ substantially according to race or gender. The more they practiced yoga, whether in years or in amount of class or home practice, the higher their odds of believing yoga improved their health.

Conclusions

Individuals who practice yoga are not free of health concerns, but most believe their health improved because of yoga. Yoga might be beneficial for a number of populations including elderly women and those with chronic health conditions.

Introduction

Background

Unhealthy lifestyle choices made by many Americans have resulted in an explosion of chronic health conditions, most notably cardiovascular disease, cancer, obesity, and Type 2 Diabetes. (1) The Surgeon General claims America is at a crossroads regarding the nation’s health and attributes the epidemic of obesity and obesity-related health conditions to three factors: decreased physical activity; increased consumption of high caloric, high fat and nutrient-poor foods; and stress.(2) Changing these negative health behaviors is critical to changing the current health trajectory of America.

Yoga, consisting of eight limbs (universal ethical principles, individual self-restraint, physical poses, breath work, quieting the senses, concentration, meditation, and emancipation), is believed to bring balance and health to the body, mind, and spirit.(3) Yoga improves symptoms associated with a number of chronic health conditions including type 2 diabetes,(4) cardiovascular disease,(5), metabolic syndrome,(6) and cancer.(7) Yoga decreases inflammation and improves immune system function,(8–10) and yoga favorably affects mental health, reducing depression(11) and anxiety.(12) Evidence suggests yoga exerts its therapeutic benefits by increasing vagal stimulation and turning off the Hypothalamic-Pituitary- Adrenal (HPA) axis and the Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS) response to stress.(6) Streeter et al. propose that yoga corrects under activity of the parasympathetic nervous (PNS) and gamma amino-butyric acid (GABA) systems, as well as decreases allostatic load, (13) the damage that occurs when the HPA-SNS stress response system becomes overtaxed and begins to function improperly.(14)

While the evidence of yoga’s positive impact on health is substantial, nearly all published research has focused on individuals with no prior yoga experience. Few published studies have focused on the health and variations of practice in individuals who practice yoga. Only two large studies examined health characteristics in yoga practitioners, and both were sub-studies of large national surveys.(15, 16) Birdee et al. found yoga practitioners (anyone practicing yoga in the past year) to be predominantly white (85%) and female (76%), with half being college educated;(15) Yoga practitioners were more likely than non-practitioners to report their health as excellent, very good, or good (95% vs. 87%, respectively; p ≤ 0.005). In an Australian study, Sibbritt et al. concluded that younger and older women who “often” used yoga reported better general health (77.2 ± 18.8 and 75.0 ± 21.9, respectively) than their counterparts who rarely used yoga (younger: M = 72.9 ± 19.2, older: M = 69.0 ± 21.2; p’s ≤ 0.005). Both younger and older women who “often” used yoga reported better mental health (72.7 ± 16.8 and 77.3 ± 16.7, respectively) than their counterparts who practiced rarely (69.9 ± 16.7 and 73.1 ± 17.3, respectively; p’s ≤ 0.005). Both studies collected minimal information regarding the length and intensity of subjects’ yoga practice, and one focused exclusively on females. No large-scale US studies have examined, in depth, the health characteristics and practice patterns of male and female yoga practitioners, including their perceptions of the impact of their yoga practice on their health.

Objectives

The purpose of this analysis is to describe the practice patterns (years of practice, number of classes per month, class size and length, days per month of home practice) and practice habits (styles of yoga practiced, types of poses practiced, breath work, and meditation) of yoga practitioners. A second objective is to describe the health habits (food choices including fruit, vegetable, and meat consumption; activity levels; smoking status; and caffeine and alcohol consumption) and health characteristics (general health, health conditions, BMI, sleep, fatigue, mindfulness, subjective well-being, and social support) of yoga practitioners, and to compare these with national norms, when available. The final objective is to explore practitioners’ beliefs regarding the relationship between their yoga practice and their health.

Methods

Study design

The researchers used cross-sectional data from a large national survey where anonymous online surveys were used to examine yoga practice, health, and health beliefs in yoga practitioners. The study was approved by the University of Maryland Institutional Review Board.

Setting and Participants

The sampling process used in this study has been described in detail elsewhere.(17) Inclusion criteria: 1) at least 18 years of age, 2) practiced yoga (in class or at home) at least once per week for at least two of the past 6 months, and 3) Internet access and ability to complete the survey. Participants were recruited from Iyengar yoga studios across the nation. Iyengar yoga, a classical form of yoga practiced around the world, has a teacher certification process that is highly structured and strictly controlled by governing agencies in the individual countries. Working with the Iyengar Yoga National Association of the United States (IYNAUS) to assure representation of all major regions of the country, the researchers selected 15 out of 100+ yoga studios. These 15 studios had email list serves of approximately 18,160. Using the random selection function in SPSS (version 19), 4307 subjects were randomly selected to receive a secure link to the survey. One thousand forty-five of the 1167 who responded to the survey link completed the questionnaire, met inclusion criteria, and were included in the final sample.

Variables and Measurement

Using SurveyMonkey®, the authors created a 65-item questionnaire that asked questions about yoga practice and health. Yoga practice questions were developed with the guidance of senior Iyengar yoga teachers.

Demographic Data

The following demographic information was collected: gender, race, age, education, job status, and marital status.

Yoga Practice Variables

Individual survey questions were used to assess: styles of yoga practiced, years of practice, classes attended per month, class size, and home practice. Home practice of yoga was defined as the number of days/month subjects practice yoga outside of class including the physical poses (vigorous poses, standing poses, inversions including shoulder stand and head stand, and gentle poses), breath work, and/or meditation.

Subjects were asked to report practice frequency (days per week or month they practice both in class and at home, on average) and amount (minutes per day) of specific yoga techniques (physical poses, breath work, and meditation). Four categories of physical poses were assessed: standing poses; vigorous poses including backbends, sun salutations, and arm balances; inversions such as head stand and shoulder stand; and gentle and/or restorative poses including Savasana (Relaxation pose). The amount of time spent studying yoga philosophy was measured using a single multiple-choice item that asked how often they study yoga philosophy, defined as attending classes or lectures (including webcasts or recordings) or reading yoga philosophy texts such as the Bagavad Gita, Yoga Sutras, and the Upanishads. A 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) was used to assess whether subjects believed that their yoga practice has benefitted various aspects of health.

Health Variables

A number of valid and reliable pre-existing measures were used to collect data on health including: fruit and vegetable consumption,(18) physical activity,(19) sleep,(20) fatigue,(20) social support,(21) subjective well-being,(22) and mindfulness.(23, 24) These variables are detailed in Table 1. Individual aspects of health were measured with one or two items including: alcohol consumption, caffeine consumption, vegetarian status, and general health. Alcohol consumption was calculated using the number of days per week and the number of drinks (12 ounces of beer, 4 ounces of wine, or 1–1/2 ounces of hard liquor) consumed, on average. Only individuals who reported consuming no meat (including poultry or fish) were considered vegetarian. Body Mass Index (BMI), a measure of body fat, was calculated using the following formula(25):[Weight (pounds)/height (inches)2] × 703. General health was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from poor (1) to excellent (5).

Table 1.

Pre-existing Measures used in the Study

| Health Variable | Measure | Number of Items | Reference Period | Description | Reliability in Present Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit & vegetables/day | Multifactor Screener | 7 | Past month | Food frequency questionnaire used in NCI’s OPEN and EATS studies. Used to calculate pyramid servings of fruits and vegetables per day. | N/A |

| Physical activity | International Physical Activity Questionnaire – Short Form (IPAQ-SF) | 7 | Past month | Subjects report average number of days per week and minutes per day of physical activity, not including yoga practice. Total score used to classify levels of physical activity (low, moderate, high). | N/A |

| Sleep disturbance | PROMIS® | 4 | Past 7 days | PROMIS® and NIH Toolbox are NIH initiatives providing a free national | .83 |

| Fatigue | PROMIS® | 4 | Past 7 days | databank of commonly used patient-reported outcome measures. Use 5-point | .90 |

| Socials support | NIH Toolbox | 8 | Past few months | Likert scales, ranging from 1 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘very much’). Standardized T Scores may be calculated from PROMIS. | .96 |

| Subjective well-being | Mental Health Continuum-Short Form | 14 | Past month | Measure of positive mental health or “happiness.” Scores used to classify individuals as flourishing, moderately mentally healthy, or languishing. | .91 |

| Mindfulness | Freiberg Mindfulness Inventory-SF | 8 | Past month | Measures mindfulness, the immediate ability to focus on the present moment without judgment. | .87 |

N/A = not applicable. PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Information System

Statistical methods

Data were cleaned to identify miscoded data, missing data, and outliers. For all variables, less than 5% of the data were missing. Only complete cases were used in analyses, and no statistically significant differences in any outcome variables were noted between complete and incomplete cases. Descriptive statistics including measures of central tendency, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages were used to describe demographic and health characteristics, yoga practice habits, and beliefs about yoga practice and health. Three yoga practice variables (frequency of gentle poses, breath work, and meditation) were badly skewed, so researchers used the median as a cut point to dichotomize these variables. The three response categories regarding beliefs about yoga practice and health were collapsed into two categories: those who agree/strongly agree that yoga practice benefits health and those who did not.

Logistic regression analyses were used to examine what demographic and yoga practice variables predicted beliefs that yoga practice improves health. For each belief outcome, potentially influential demographic predictors were identified with logistic regression. Demographic variables that predicted each outcome at p < .20 in simultaneous analysis were included with chronic disease presence and yoga practice variables as predictors of these beliefs.

Gender differences in yoga practice were analyzed using independent t tests for continuous variables and Chi square tests for categorical variables. SPSS 19.0 was used for all analyses, and all inferential tests were conducted at the 0.05 level of significance.

Results

Demographic characteristics of subjects are shown in Table 2.(17) Subjects were predominantly female (84.2%), white (89.2%), and highly educated, 90% having either an undergraduate (36.9%), master’s (37%) or a doctoral (13.5%) degree. Because many of the selected studios had teachers known regionally or nationally, subjects were from all states except: Arkansas, Indiana, Kansas, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Utah, and West Virginia.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of final sample (n =1045 unless specified)

| Variables | M (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Age (n =1043) | 51.7(11.7) | 19–87 |

| Frequency | Percent | |

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Male | 165 | 15.8 |

| Female | 880 | 84.2 |

| Race | ||

| White | 932 | 89.2 |

| Multiracial | 38 | 3.6 |

| Asian | 28 | 2.7 |

| African American | 18 | 1.7 |

| American Indian / Alaskan/ Hawaiian/ Pacific Islander | 6 | 0.6 |

| Other | 23 | 2.2 |

| Marital Status* | ||

| Married/Lives with partner | 730 | 69.8 |

| Single, never married | 164 | 15.7 |

| Widowed/separated/divorced | 144 | 13.8 |

| Other | 7 | 0.7 |

| Employment | ||

| Full time | 532 | 50.9 |

| Part time | 277 | 26.5 |

| Not employed | 236 | 22.6 |

| Education* | ||

| High School grad/GED/Vocational School/Some college | 130 | 12.6 |

| College graduate | 386 | 36.9 |

| Master’s degree | 387 | 37.0 |

| Doctoral degree | 141 | 13.5 |

Significant gender differences exist. Men had lower odds of being married or living with a partner (OR = 0.59, p ≤ .01) and having a college degree or higher education (OR = 0.53, p ≤ .01) than females.

Yoga Practice

Yoga practice characteristics are displayed in Table 3. Participants had practiced yoga from 2 months to more than 25 years (M = 11.4 ± 7.5). Nearly all (n = 927; 88.7%) took yoga classes, averaging 6.1 (± 5.1) classes per month. Most (n = 935; 89.5%) reported practicing yoga outside of class (M = 12.2 ± 9.7 days per month). The majority reported performing all elements of yoga practice including: gentle poses (97.6%); standing poses (97.3%); inverted poses such as head stand and/or shoulder stand (86.8%), vigorous poses such as arm balances, backbends and/or sun salutations (85.8%); breath work (71.2%); and meditation (62.9%).

Table 3.

Yoga practice characteristics

| Yoga Practice Variable | n | M (SD) | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of practice | 1045 | 11.4 (7.5)* | 11.0 | 0 – 25+ |

| Classes/month | 1045 | 6.1 (5.1) | 4.0 | 0–28 |

| Class length in minutes | 926 | 89.1 (15.2) | 90.0 | 0–180 |

| Students per class | 926 | 13.3 (6.9) | 12.0 | 1–50 |

| Practice days/month | 1045 | 12.2 (9.7) | 12.0 | 0–28 |

| Minutes of practice/typical day | 923 | 43.7 (30.6) | 30.0 | 1–180 |

| Minutes per day of practice (by type)** | ||||

| Standing poses | 1017 | 23.0 (13.9) | 20.0 | 1–90 |

| Vigorous poses | 897 | 21.9 (16.5) | 20.0 | 1–90 |

| Inversions | 908 | 9.4 (7.2) | 8.0 | 1–60 |

| Gentle poses | 1020 | 21.1 (21.3) | 15.0 | 1–120 |

| Breath work | 744 | 17.5 (14.1) | 15.0 | 1–90 |

| Meditation | 657 | 17.5 (14.5) | 15.0 | 1–120 |

| Frequency | Percent | |||

|

| ||||

| Philosophy study | ||||

| Never | 274 | 26.2 | ||

| < once per month | 394 | 37.7 | ||

| 1–8 times per month | 269 | 25.7 | ||

| ≥ 3 times per week | 107 | 10.4 | ||

| Style of Yoga Practiced | ||||

| Iyengar only | 819 | 78.4 | ||

| Iyengar and 1+ other style | 161 | 15.4 | ||

| Unknown/Other style | 65 | 6.2 | ||

Mean number of years of yoga practice was significantly different in men (M = 10.33 ± 7.611) and women (M = 11.59 ± 7.49; t = 1.974, df = 1043; p <.05).

Minutes per day of practice (in class and at home) on a typical day when practicing these poses.

Health Characteristics

Health characteristics are shown in Table 4. Overall, more than 85% reported their health as very good (46.3%) or excellent (38.8%), although close to 60% reported a chronic or serious health condition. Among the conditions reported were: mental health conditions including anxiety or panic attacks (15.4%) and depression (24.8%); arthritis (17.8%); hypertension (10.7%); headaches (13.6%); and asthma (10.6%).

Table 4.

Health characteristics of study sample (N = 1045)

| Health Variable | Mean (SD) | Median | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (n =1034) | 23.1 (3.9)* | 22.4 | 12.1–49.4 | |

| Fruits and Vegetables/day (1043) | 6.1 (1.1)* | 5.56 | 1.8–18.2 | |

| Caffeine (cups/day) | 1.7 (1.4)* | 2.0 | 0.0–15.0 | |

| Alcohol intake | ||||

| Days/week | 2.4 (2.3) | 2.0 | 0.0–7.0 | |

| Drinks/day (n =1043) | 1.1 (1.0) | 1.0 | 0.0–8.0+ | |

| Sleep Disturbance | 8.0 (3.0) | 7.0 | 4.0–20.0 | |

| Fatigue | 7.6 (2.9) | 7.0 | 4.0–20.0 | |

| Social Support | 34.9 (5.6)* | 37.0 | 11.0–40.0 | |

| Subjective well-being | 52.3 (11.0)* | 54.0 | 9.0–70.0 | |

| Mindfulness | 24.0 (4.3) | 24.0 | 8.0–32.0 | |

| Health Variable | Frequency | Percent | ||

|

| ||||

| General Health | ||||

| Excellent | 405 | 38.8 | ||

| Very good | 484 | 46.3 | ||

| Good | 136 | 13.0 | ||

| Fair | 17 | 1.6 | ||

| Poor | 3 | 0.3 | ||

| Smoking History | ||||

| Never smoked | 572 | 54.7 | ||

| Quit smoking | 452 | 43.3 | ||

| Still smoking | 21 | 2.0 | ||

| Physical Activity Category | ||||

| Low | 176 | 16.8 | ||

| Moderate | 396 | 37.9 | ||

| High | 473 | 45.3 | ||

| Total reporting 1+ health condition | 761 | 72.8 | ||

| Total reporting 1+ chronic or serious health condition | 626 | 59.8 | ||

Significant gender differences were noted in BMI (men: M = 24.74 ± 3.32; women: M = 22.77 ± 3.87; p < .001), fruits and vegetables per day (men: M = 6.27 ± 2.90; women: M = 5.64 ± 1.69; p < .001), caffeine (men: M = 2.0 ± 1.82; women: M = 1.59 ± 1.24; p <.01), subjective well-being (men: M = 49.56 ± 11.74; women: M = 52.77 ± 10.76; p <.01), and social support (women: M = 35.199 ± 5.283; men: M = 32.958 ± 11.74; p < .001).

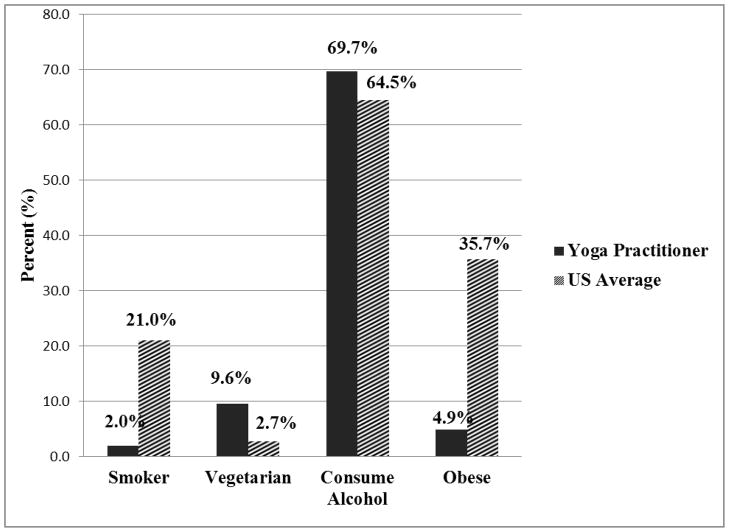

Select comparisons between study subjects and the general U.S. population are shown in Figure 1. Subject’s BMI ranged from 12.1 to 49.4 (M = 23.1 ± 3.9). Nearly all subjects (95.1%) had BMI’s below those considered obese (defined as BMI ≥ 30). This compares very favorably to the 35.7% obesity rate in the general U.S population.(26) On average, participants consume between two and 18 servings of fruits and vegetables per day (M = 6.1 ± 1.1 servings). The median intake of 6.1 servings per day for men (n =164) and 5.5 for women (n =879) compared favorably with national norms found in the National Cancer Institute’s Observing Protein and Energy (OPEN) Study, where the median intake of fruits and vegetables per day was 5.3 for men (n =261) and 4.7 for women (n =223).(18) Nearly 10% follow a vegetarian diet, consuming no meat, fish, or poultry, almost four times the rate of vegetarianism (2.7%, n = 2397) found in the general US population.(27)

Figure 1. Comparisons of health characteristics between yoga practitioners and national norms.

National norms obtained from: Smoking and alcohol: CDC, Vital and health statistics summary health statistics for US adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2010, US Department of Health and Human Services Center for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, Maryland. Vegetarian: VRG, ‘How many adults are vegetarians?’ A vegetarian resource group asked in a 2009 poll. Vegetarian Journal, 2009(4). Obesity: Ogden, C., et al., Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010, 2012, National Center for Health Statistics: Hyattsville, MD.

Overall, subjects were very physically active, above and beyond their yoga practice. The majority reported levels of physical activity categorized as moderate (37.9%) or high (45.3%). While 43.3% reported a past history of smoking, only 21 of 1045 subjects were current smokers (2%). This compares very favorably with a 21% smoking rate in the general U.S. population.(28)

Subjects reported drinking about 1.5 caffeinated beverages per day (M = 1.7 ± 1.1 cups), slightly lower than the US average of 280 mg/day (about three cups of coffee).(29) Seven hundred and twenty nine (69.7%) reported consuming alcohol, slightly above the 64.5% of American adults who report being current drinkers.(28) On average, they consume about one drink of alcohol (M = 1.1 ± 1.0), two to three times per week (M = 2.4 ± 2.3 days).

Subjects reported levels of sleep disturbance (M = 8.0 ± 3.0) and fatigue (M = 7.6 ± 2.9) on the lower end of the possible range of scores (4 to 20). Mean T scores for sleep disturbance (M = 44.9 ± 7.6 and for fatigue (M = 46.2 ± 8.0) compared favorably to national norms (M = 50 ± 10; p >.05).(20) Scores for social support were on the higher end of the possible range of scores (M = 34.9 ± 5.6, range = 8–40).

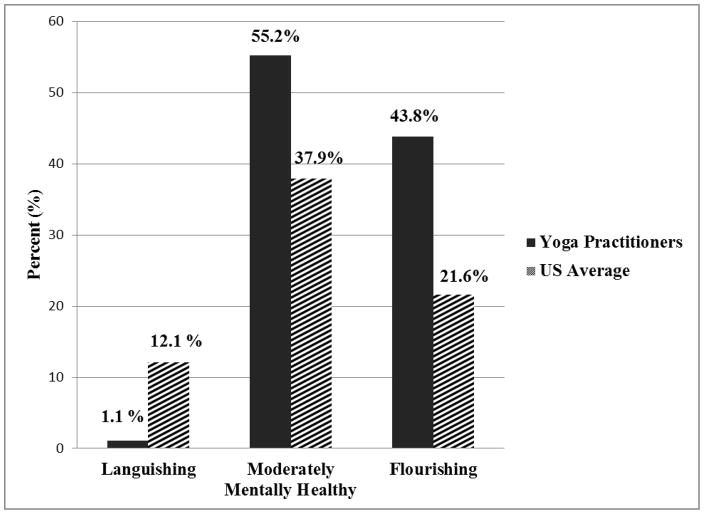

Subjective well-being scores placed nearly all subjects in a mental health category of either moderately mentally healthy (55.2%) or flourishing (43.8%), and only about 1% were languishing. These numbers compared favorably with those of a nationally representative sample of individuals age 25–74 in the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study,(30) in which only 21.6% were flourishing, while 58.7 were moderately mentally healthy and 12.1% were languishing (Figure 2). Mindfulness scores (M = 24.0 ± 4.3) were in the upper range of possible scores (range = 8–32).

Figure 2. Comparison of mental healtha of yoga practitioners to national normsb.

a = mental health measured using Mental Health Continuum-short form. b= national norms from the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study.

Perceptions of the Relationship between Yoga and Health

Subjects generally reported positive associations between yoga and health (Table 5). The large majority agreed or strongly agreed that their yoga practice improved their general health (89.5%), energy level (84.5%), and happiness (86.5%). The majority agreed or strongly agreed that yoga improved their sleep (68.5%) and their interpersonal relationships (67.0%). Over half agreed or strongly agreed that yoga helped them attain or maintain a healthier weight (57%), and just under half agreed or strongly agreed (47.0%) that their diet was better because of yoga.

Table 5.

Results of Likert scale* questions about subject’s beliefs regarding the impact of yoga on various aspects of health (N = 1045)

| Belief about Yoga and Health | Level of Agreement | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Strongly Disagree/ Disagree | Neither Agree nor Disagree | Agree/ Strongly Agree | |

| Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | Frequency (%) | |

| My sleep is better because of yoga | 50(4.8%) | 279 (26.7%) | 716 (68.5%) |

| My energy level is better because of yoga | 34(3.3%) | 128 (12.2%) | 883 (84.5%) |

| My health has improved because of yoga | 35(3.3%) | 75 (7.2%) | 935 (89.5%) |

| My diet is better because of yoga (n =1027) | 107 (10.4%) | 438 (42.6%) | 482 (47.0%) |

| Yoga has helped me to attain or maintain a healthier weight (n =1012) | 101 (10.0%) | 331 (32.7%) | 580 (57.3%) |

| I drink less or no alcohol because of yoga | 300 (28.7%) | 513 (49.1%) | 232 (22.2%) |

| My relationships with others are better because of yoga | 57 (5.5%) | 287 (27.5%) | 700 (67.0%) |

| I am happier because of yoga | 36 (3.3%) | 107 (10.2%) | 903 (86.5%) |

All questions used a 5-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, or strongly agree).

Predictors of Beliefs That Yoga Practice Benefits Health

A summary of odds ratios predicting beliefs that yoga improves each of the eight aspects of health from influential demographic predictors in combination with yoga practice variables is shown in Table 6. The number of classes taken per month positively predicted all eight beliefs about yoga practice and health (p’s ≤ .05), and the frequency with which one practices yoga at home predicted all beliefs about the health benefits of yoga (p’s ≤ .001) except the beliefs that yoga improves general health (p = .067) and improves happiness (p = .347) . Taking one additional class per week increased one’s odds of believing yoga improves one’s overall health by 32%, while practicing outside of class an additional three days per week increased one’s odds of believing that yoga improves one’s sleep, energy, diet, weight and interpersonal relationships a little over 45%. Individuals who attended more yoga classes (p = .008) and practiced at home more frequently (p .001) were more likely than those who practiced and attended classes less frequently to believe that yoga practice improves energy. Those with more years of yoga practice (p ≤ .001), higher class and practice frequency (p’s ≤ .001), and the presence of one or more chronic health conditions (p = .035), have higher odds of agreeing that yoga improves one’s weight. Likewise, individuals with more years of yoga practice (p ≤ .001), higher class frequency (p ≤ .001), higher practice frequency (p ≤ .001), and one or more chronic health conditions (p = .05) were more likely to believe yoga improves their interpersonal relationships.

Table 6.

Odds Ratios with 95% confidence intervals in final models predicting beliefs that yoga practice improves health (N = 1045)

| Predictor | Belief: “Yoga improves….” | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sleep (n =1027) | Energy | Health | Diet | Weight (n =1012) | Alcohol intake | Relationships | Happiness | |

| Age | 0.98*** (0.96, 0.99) | 0.98** (0.97, 0.99) | ||||||

| Gendera | 1.28 (0.88, 1.88) | |||||||

| Raceb | 0.65* (0.43, 0.98) | |||||||

| Employmentc | 1.84** (1.18, 2.86) | 1.50* (1.09, 2.05) | ||||||

| Marital Statusd | 0.52*** (0.38, 0.72) | |||||||

| Educatione | 0.74 (0.48, 1.13) | 0.81 (0.45, 1.44) | 1.03 (0.69, 1.53) | 0.89 (0.58, 1.38) | 1.67* (1.01, 2.75) | |||

| Chronic Health Conditionf | 1.03 (0.78, 1.35) | 1.16 (0.82, 1.64) | 1.46 (0.98, 2.20) | 1.16 (0.89, 1.52) | 1.33* (1.02, 1.73) | 1.26 (0.92, 1.73) | 1.32* (1.00, 1.74) | 1.22 (0.85, 1.75) |

|

| ||||||||

| Yoga Practice Predictors | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Years of Practice | 1.01 (.99, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 1.04*** (1.02, 1.06) | 1.04*** (1.02, 1.06) | 1.04*** (1.02, 1.06) | 1.05*** (1.03, 1.07) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) |

| Practice Frequencyg | 1.03*** (1.01, 1.05) | 1.04*** (1.02, 1.62) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 1.04*** (1.03, 1.06) | 1.03*** (1.01, 1.04) | 1.05*** (1.04, 1.06) | 1.04*** (1.02, 1.06) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) |

| Class Frequencyh | 1.05*** (1.02, 1.08) | 1.06** (1.02, 1.10) | 1.08** (1.03, 1.14) | 1.06*** (1.03, 1.09) | 1.05*** (1.02, 1.08) | 1.04* (1.01, 1.07) | 1.10*** (1.06, 1.13) | 1.11*** (1.06, 1.17) |

= coded females ‘0’, males ‘1’.

= coded ‘0’ = non-white, ‘1’ = white.

coded ‘0’ = not currently employed, ‘1’ = employed full or part time.

coded ‘0’ = not married or living with a partner, ‘1’ = married or living with a partner.

‘0’ = education less than college graduate, ‘1’ = college graduate or higher.

= ‘0’ = no chronic or serious health condition reported, ‘1’ = one or more chronic or serious health conditions reported.

= days per month of yoga home practice.

= days per month of yoga classes.

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001

Gender Differences

There were few gender differences in the demographics of the sample. Men were about 60% less likely than women to be married or living with a partner (OR = 0.59, p = .003), and women were about 50% more likely to hold a college degree than men (OR = 0.53, p = .004). Men and women differed in a number of aspects of health. Women (M = 52.77 ± 10.76) were significantly happier than men (M = 49.56 ± 11.74, p =.001) and reported significantly higher levels of social support (women: M = 35.199 ± 5.283; men: M = 32.958 ± 11.74, p < .001). Men had significantly higher BMI (M = 24.74 ± 3.32; women: M = 22.77 ± 3.87, p < .001) and consumed more fruits and vegetables per day (men: M = 6.27 ± 2.90; women: M = 5.64 ± 1.69, p < .001) and caffeine (men: M = 2.0 ± 1.82; women: M = 1.59 ± 1.24, p = .006).

There was only one gender difference in yoga practice. On average, female participants (M = 11.59 ± 7.49 years) had practiced yoga about one year longer than men (M = 10.33 ± 7.611, p = .049). Otherwise, men and women were not statistically different when it came to the practice of yoga.

Discussion

Like the study by Birdee et al,(15) yoga practitioners in this study were predominantly female, white, and educated. Participants in this study reported lower levels of obesity (4.9%) than the 10% found in Birdee’s sample of yoga participants (15) and in the general population (35.7%).(26) One possible reason for this study’s lower levels of obesity may be that Birdee et al. defined a yoga practitioner as any individual who practiced yoga during the past 12 months,(15) while the current study defined a yoga practitioner as one who practiced yoga at least weekly for a minimum of two of the past 6 months.

A strong argument against drawing any conclusions about yoga and health from cross-sectional surveys of yoga practitioners is the element of “self-selection” in which only healthy individuals choose to practice yoga. Thus, positive health outcomes may have no relationship with yoga practice. One interesting finding in this study that counters this argument is that, when asked about any current or past history of illness, nearly 60% reported at least one chronic or serious health condition. Yet 90.5% (n = 567) of the 626 subjects reporting a chronic or serious health condition agreed or strongly agreed that their health has improved because of yoga. The mental health of this subset was also excellent, as 43.6% (n = 273) scored in the range of flourishing and only 1.3% (n = 8) were languishing.

Perhaps more importantly, participants’ health status did not predict their beliefs about yoga and health. Compared with healthier yoga practitioners, individuals with chronic health conditions were no less likely to believe yoga improved their general health, sleep, energy, diet, weight, relationships, levels of happiness and alcohol consumption. Whether individuals with health conditions practice yoga to improve their health or to alleviate their symptoms cannot be determined from this cross-sectional study. However, 16% of yoga practitioners in the study by Birdee et al. reported practicing yoga to treat a specific health condition.(15)

Similarly, Depression was reported by 24.8%, much higher than the lifetime prevalence of 16.2% in the general US population.(31) Yet the large majority of subjects considered themselves in very good (46.3%) or excellent (38.8%) health, and 43.3% reported mental health continuum scores considered “flourishing.” Even the subset of 242 subjects reporting a history of depression reported excellent mental health, with 41.7% (n = 108) flourishing and 49% (n = 127) moderately mentally healthy.

It is not surprising that the more an individual does yoga, the more strongly they believe yoga improves their health. Regardless of whether one does yoga for many years or practices yoga in class or at home, individuals who practice yoga believe that it benefits their health. What is not clear is whether having these beliefs leads them to seek yoga to improve their health, or whether their strong beliefs emerge after they see the therapeutic benefits of yoga practice firsthand.

While the amount of yoga one does increased the odds of believing yoga improves health, demographics did not play a large role in predicting these beliefs. Gender made no difference in beliefs about the health benefits of yoga, and race made only a slight difference in the belief that yoga improves one’s diet. In other words, regardless of age, race, gender, or education levels, yoga practitioners tend to hold similar beliefs about the impact of yoga practice on their health. While one could argue that this sample compared favorably to national norms in a number of health outcomes solely because the participants were educated white women, a demographic group that would inherently fare better compared to national norms, regardless of yoga practice. However, one’s race, education, and gender did not significantly affect their beliefs about the health benefits of yoga. Non-white, non-college graduates were as likely to believe that yoga improved sleep, energy, weight, alcohol consumption, relationships, and general health as non-white, individuals who were not college graduates.

On the whole, the men and women in this sample were nearly identical when it came to yoga practice. Women overall were happier than men and reported more social support, while men had higher BMI’s and consumed more fruits, vegetables and caffeinated beverages. Similar gender differences in social support,(32) BMI,(33) consumption of fruits and vegetables,(18) and caffeine(34) have been found in the general population. Overall, subjective well-being does not differ by gender, although older women (over 45 years of age) have been found to be less happy than their male counterparts.(35) Higher levels of subjective well-being in these female yoga practitioners are interesting, given that their mean age was 51.68 (11.7) years. Perhaps yoga may provide psychological benefits that are particularly valuable for elderly women.

Age also behaved in an interesting manner in the researchers’ previous analyses of this population.(17) While older individuals commonly experience higher rates of fatigue and sleep disturbances,(36, 37) no such relationship existed in this population of yoga practitioners. Sleep disturbance was unrelated to age, and fatigue levels significantly decreased with age. Physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption also improved with age in this population.

While the findings of this study are interesting, several limitations exist. Anonymous internet surveys are at risk for recall bias and deception. The participants were randomly selected to receive the survey, but the low response rate (<30%) and the element of self-selection in those who responded might have biased the results. While practitioners from 41 states were included, it is not clear if the omission of nine states may have affected the results. However, the omitted states contained both the healthiest (Utah) and the unhealthiest (West Virginia) states, with the remaining seven states distributed evenly between the two. (38) Thus, it appears unlikely the omission resulted in the sample being drastically skewed regarding health. Finally, cross-sectional studies that rely on self-reports and lack comparison groups are inherently weaker than randomized controlled trials, rendering it impossible to draw definitive conclusions about yoga and health from this study.

Despite these limitations, the findings of this study are compelling. While the discipline of yoga seems to draw educated white women, practitioners of all races and both genders were in agreement that yoga improved their health. The more they practiced yoga, whether in years, number of classes, or amount of home practice, the higher their odds of believing yoga improved their health. These findings imply that yoga practice might be beneficial for a number of populations including elderly women and those with chronic health conditions, especially depression. Because the demographics of those who choose yoga are skewed toward white, educated females, studies are needed to examine what barriers exist to yoga practice among minorities and men. While a number of randomized clinical trials have shown yoga to improve symptoms associated with a number of chronic health conditions, (5–7, 11) most of these studies were of short duration (< 4 months). The true benefits of yoga practice may take much longer to accumulate; thus, large scale, long-term longitudinal studies are needed to fully understand yoga’s impact on health.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Kathleen Pringle of the Iyengar Yoga National Association U.S., Advanced Iyengar yoga teacher John Schumacher, and all of the yoga studio owners for their assistance in the development and implementation of the survey.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.CDC. The Power of Prevention: Chronic Disease…the Public Health Challenge of the 21st Century. Atlanta: GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.USDHHS. The Surgeon General’s Vision for a Healthy and Fit Nation. Rockville, MD: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iyengar BKS. Light on Yoga: Yoga Dipika. 2. New York: Schocken Books; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Innes K, Vincent H. The influence of yoga-based programs on risk profiles in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2007;4:469–486. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Raub JA. Psychophysiologic effects of Hatha Yoga on musculoskeletal and cardiopulmonary function: a literature review. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2002;8:797–812. doi: 10.1089/10755530260511810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Innes K, Bourguignon C, Taylor A. Risk indices associated with the insulin resistance syndrome, cardiovascular disease, and possible protection with yoga: A systematic review. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2005;18:491–519. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.6.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bower JE, Woolery A, Sternlieb B, Garet D. Yoga for cancer patients and survivors. Cancer Control. 2005;12:165–171. doi: 10.1177/107327480501200304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pullen PR, Nagamia SH, Mehta PK, et al. Effects of Yoga on Inflammation and Exercise Capacity in Patients With Chronic Heart Failure. Journal of Cardiac Failure. 2008;14:407–413. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stück M, Rigotti T, Mohr G. Evaluation of a stress regulation and coping training for teachers. Untersuchung der Wirksamkeit eines Belastungsbewältigungstrainings für den Lehrerberuf. 2004;51:234–242. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao RM, Telles S, Nagendra HR, et al. Effects of yoga on natural killer cell counts in early breast cancer patients undergoing conventional treatment. Medical Science Monitor. 2007;13(2):CR57–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uebelacker L, Epstein-Lubow G, Guidiano B, et al. Hatha yoga for depression: critical review of the evidence for efficacy, plausible mechanisms of action, and directions for future research. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2010;16:22–33. doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000367775.88388.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li A, Goldsmith C. The effects of yoga on anxiety and stress. Alternative Medicine Review. 2012;17:21–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Streeter C, Gerbarg P, Saper R, Ciraulo D, Brown R. Effects of yoga on the autonomic nervous system, gamma-aminobutyric-acid, and allostasis in epilepsy, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Medical Hypotheses. 2012;78:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2012.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McEwen BS. The Neurobiology of stress: From serendipity to clinical relevance. Brain Research. 2000:886. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02950-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birdee GS, Legedza AT, Saper RB, et al. Characteristics of yoga users: results of a national survey. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23:1653–1658. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0735-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sibbritt D, Adams J, van der Riet P. The prevalence and characteristics of young and mid-age women who use yoga and meditation: Results of a nationally representative survey of 19,209 Australian women. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2011;19:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross A, Friedmann E, Bevans M, Thomas S. Frequency of yoga practice predicts health: Results of a national survey of yoga practitioners. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/983258. Article ID 983258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson FE, Midthune D, Subar AF, et al. Performance of a short tool to assess dietary intakes of fruits and vegetables, percentage energy from fat and fibre. Public Health Nutrition. 2004;7:1097–1106. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Craig C, Marshall A, Sjostrom M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2003;35:1381–1395. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.PROMIS. Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System: Dynamic Tools to Measure Health Outcomes From the Patient Perspective. Retrieved January 31, 2011 from http://www.nihpromis.org/default.aspx.

- 21.Gershon RC, Cella D, Fox N, et al. Assessment of neurological and behavioural function: the NIH Toolbox. The Lancet Neurology. 2010;9:138–139. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robitschek C, Keyes CLM. Keyes’s model of mental health with personal growth initiative as a parsimonious predictor. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2009;56:321–329. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walach H, Buchheld N, Buttenmüller V, Kleinknecht N, Schmidt S. Measuring mindfulness-the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI) Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;40:1543–1555. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohls N, Sauer S, Walach H. Facets of mindfulness - Results of an online study investigating the Freiburg mindfulness inventory. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;46:224–230. [Google Scholar]

- 25.NHLBI. Clinical Guildlines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Oobesity in Adults: The EvidenceReport. Retrieved February 2, 2011; from http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/obesity/ob_gdlns.pdf.

- 26.Ogden C, Carroll M, Kit B, Flegal K. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.VRG. ‘How many adults are vegetarians?’ A vegetarian resource group asked in a 2009 poll. Vegetarian Journal. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 28.CDC. Vital and health statistics summary health statistics for US adults: National Health Interview Survey. Hyattsville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services Center for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Julliano LM, Griffiths RR. A critical review of caffeine withdrawal: Empirical validation of symptoms and signs, incidence, severity, and associated features. Psychopharmacology. 2004;176:1–29. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2000-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keyes CLM. The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43:207–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of Major Depressive Disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felsten G. Gender and coping: Use of distinct strategies and associations with stress and depression. Anxiety, Stress and Coping. 1998;11:289–309. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010;303:235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frary CD, Johnson RK, Wang MQ. Food sources and intakes of caffeine in the diets of persons in the United States. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105:110–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Inglehart R. Gender, aging, and subjective well-being. International Journal of Comparative Sociology. 2002;43:391–408. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morelli V. Fatigue and Chronic Fatigue in the elderly: Definitions, diagnoses, and treatments. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 2011;27:673–686. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Surani S, Khan A. Sleep related disorders in the elderly: An overview. Current Respiratory Medicine Reviews. 2007;3:286–291. [Google Scholar]