Summary

Recent health policy initiatives designed to improve care coordination have stimulated the resurgence of the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model. The details of how primary and specialty care are coordinated within the PCMH model are of interest to specialists. A good medical home “neighbor” must adhere to principles that complement the PCMH team-based approach and personal relationship to the patient. One issue for neurologists considering participation in this model is whether they will function as the principal physician for some patients, only in the role of a consultant, or take some new role. It is too early to suggest any one payment method as superior, or establish the appropriate capitation fees for practicing neurologists. Recommendations are provided for neurologists considering participation in a PCMH neighborhood.

The national imperative to improve access, quality, safety, and the value of health care in the United States will have both anticipated and unanticipated consequences. Many of those consequences will affect the relationship between patients and providers.1 New roles are being defined that emphasize coordination of care and collaboration between providers. These changes will impact neurologists, who have traditionally provided a wide range of services from one-time consultation to ongoing principal care. The present effort to codify new roles and the coordination of care across these roles compels neurologists to reevaluate their existing relationships with patients and other providers, understand the changing environment, and determine the best way to engage in this process.

The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and its members encourage efforts to improve the access of patients with neurologic illnesses to the most effective health care. The AAN recognizes that addressing value requires collaborative debate with changes at all levels of health care from individual providers, practices, health care systems, and patients and their representatives. The AAN asserts a dual role in health care reform: as a resource to members adapting to changes and as an advocacy organization committed to advancing the care of patients with neurologic diseases in practices, hospitals, health care systems, and communities.

This article seeks to educate neurologists about the changes occurring as part of health care reform and to provide tools to facilitate their involvement. We describe a new model of providing specialty health care for patients with neurologic diseases in the “neighborhood” of the patient-centered medical home (PCMH).

The patient-centered medical home: A model to enhance continuity and coordination of care

The PCMH was initially introduced by the American Academy of Pediatrics in the 1960s. Recent initiatives designed to improve patient care coordination stimulated resurgence of this model. Primary care specialty societies released a joint set of principles for the PCMH in 2007.2 The PCMH model is focused on creating a central hub of patient information, with an emphasis on coordination of patient care and patient involvement in medical care.

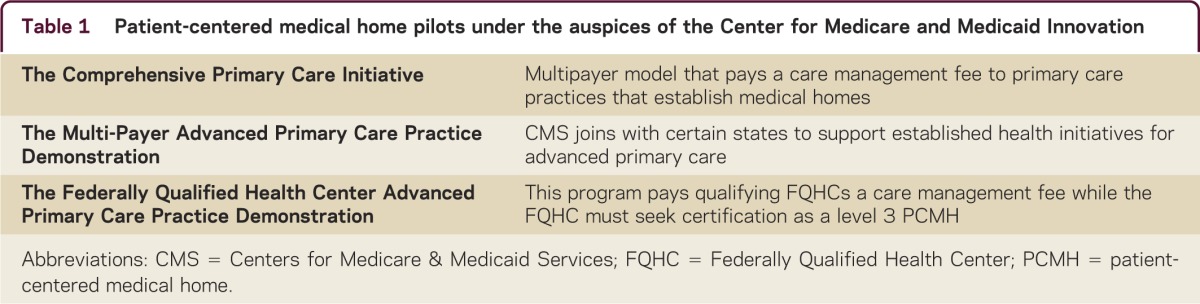

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) of March 2010 made the PCMH into policy. The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, created by the PPACA, is running 3 projects to evaluate the PCMH, documented in table 1. There are also several PCMH demonstration pilot projects taking place around the country; preliminary data on the effectiveness of these projects are starting to be published.3

Table 1.

Patient-centered medical home pilots under the auspices of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation

The role of specialists

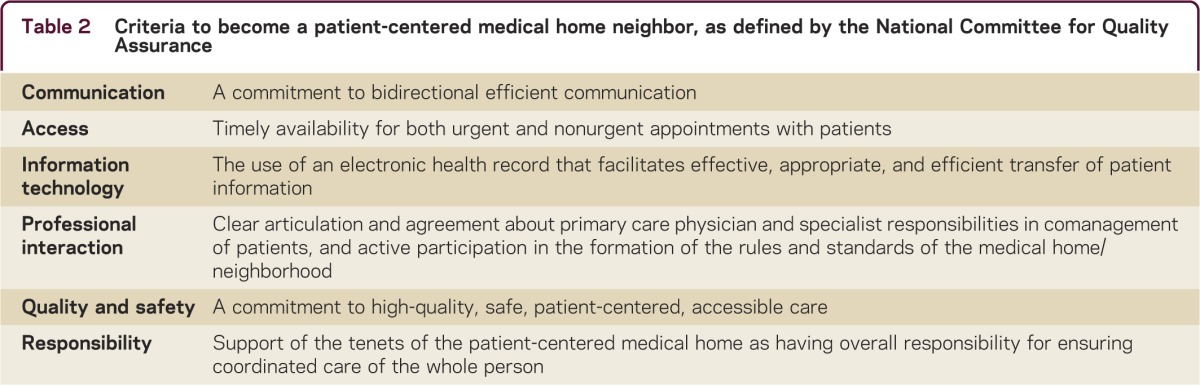

The reemergence of the PCMH model stimulated interest in the ways that primary and specialty care are coordinated. In keeping with the medical home concept, the involvement of collaborating specialists evokes the idea of a patient-centered medical home neighborhood (PCMH-N). Whereas the PCMH centers on a primary care team with a very personal relationship to the patient, a good medical home neighbor must adhere to a complementary set of principles. The National Committee for Quality Assurance has proposed several specific criteria that a specialist must meet to be certified as a PCMH-N, as described in table 2.4

Table 2.

Criteria to become a patient-centered medical home neighbor, as defined by the National Committee for Quality Assurance

In brief, a good neighbor is a specialist who works toward effective integration and coordination of services with the PCMH, no matter which practice model is chosen.

It is extremely important to clarify in advance how the PCMH and specialists will work together. Arrangements described by the American College of Physicians (ACP) include preconsultation, in which triage and a determination of urgency is determined. This initial point of contact may result in simply a "curbside" consultation where an assessment can be made without consultation and the PCMH physician institutes management. Alternatively, the physicians together may decide on a formal consultation or possibly even the need for the neurologist to take over the role of PCMH. It is then that the role of the neurologist will be defined.

The role of the neurologist

The fundamental issue at stake for a neurologist is whether the focus of care should be approached from that of a primary care physician (PCP), the neurologist as principal physician, or that of a specialist on referral. The ACP has delineated 4 possible interactions. The first is a preconsultation exchange, intended to triage and expedite care. It may be an opportunity to avoid an inappropriate referral for consultation, or to ensure appropriate referral. Second is a formal consultation to answer a discrete question or perform a procedure. Third is to comanage the patient in a shared way, to take over principal care for a limited period, or to provide principal care for an indefinite period of time. Fourth is to transfer the patient to a specialty PCMH for the entirety of care as may be the case at end of life, or with specific chronic illnesses.

We recommend that the neurologist, or other specialist, take an active part in the formation and definition of roles within the PCMH-N model to allow for a range of choices in that model that best represents certain practice styles. Neurologists might declare themselves as the PCP for a patient with degenerative diseases like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson disease, or dementia. Other neurologists may wish to maintain their referral practice in the neighborhood, while others may elect to join the medical home in the role of “formal consultant.”

While the model allows for a number of roles for a specialist, there may be barriers to specialty participation as principal care physicians. Despite the AAN's advocacy of neurologists as such principal care providers, each neurologist or neurology group should clarify what roles will be allowed or supported under a particular contract operating under a medical home model. As yet, there is no standard contract.

Financial considerations

Once the basic decisions about roles are made, questions arise regarding compensation.5 Seen in the context of health care payment reform, compensation models likely include fee-for-service vs “risk contracting.” In risk contracting, the physician takes on the care of the patient for a fixed fee (this may be referred to as a capitated fee). The physician bears risk for the costs of that treatment no matter how extensive. There are usually adjustments for levels of risk in such a contract that reflect the level of severity of illness or presence of comorbid conditions. Depending upon how that relationship is structured, the physician is paid for all or some efforts to care for that patient. Other specialty services such as diagnostic tests may be paid on an “average wholesale price” model, or a discounted amount. From the perspective of a neurologist as a member of a multispecialty group, the capitated payment for such contracting may appear as salary, with a bonus structure including some percentage of any savings. Such savings may be due to reductions in the overall cost of care, examples of which may include decreased hospitalization, fewer emergency department visits, and less repeat testing.

There is a long history of payment mechanisms for specialist services within a multispecialty group on a per-patient basis. In some cases, the specialist was paid on a fee-for-service basis, with discounted fees in instances when large numbers of patients were seen. In other cases, the PCPs were paid on a fee-for-service basis from a pool of funds paid to the group, and medical specialists were “capitated” for basic services provided. The assumption behind the latter model was that the specialist was not providing ongoing care, but rather would provide answers to specific questions. Capitation fell into disrepute due to public perception that physicians were being rewarded to limit interactions with patients. However, more recent plans for accountable care organizations (ACOs) and Medicare negotiations have revived the annual per-patient basis for payment, this time adjusted for severity of illness and tempered by quality measures to improve. Payment models in these ACOs are beyond the scope of this article, but may parallel models used in the PCMH-N.

It is too early to suggest a fee-per-patient case for neurology services. However, insurers have good data about per-patient per-month fees for medical specialists. These data should be analyzed to learn more about specialist-driven evaluation and management payments, volumes of diagnostic testing, and costs of pharmaceutical and other treatments ordered. From these data, the AAN can establish a baseline for model fees for specialists under a medical neighborhood contract.

Recommendations

Neurologists should begin to assess the nature of their interactions with their primary care colleagues, and how they add value through providing principal care vs consultative care for select patients (e.g., epilepsy, multiple sclerosis). Practice arrangements and how neurologists function within them will determine compensation within the PCMH model. These arrangements are variable, and include academic, multispecialty group, hospital-based, or other ad hoc practice types. Since the success of the PCMH-N model relies on effective communication among providers and patients, there is also a critical role for the organizations such as hospital, university, or even insurer to effectively develop and implement rules and codes of conduct for all participants.

The relationships between stakeholders in this model are highly interdependent. To refine their roles in the model effectively, neurologists need additional information. Neurologists who are considering participation in a PCMH-N should ensure the following:

There should be sufficient information made available about the roles, responsibilities, cost assignment, and the compensation structure before joining a “neighborhood” arrangement.

-

There should be reasonable estimates of compensation for the roles that the neurologist will assume. Care is improved by spending time doing sidebar consultation or preconsultation with other providers and should be valued. There needs to be recognition of the work associated with consultative, collaborative, and principal care. Guidelines include the following:

The calculation of appropriate fees for a specialist has been established and are already in use in a variety of multispecialty environments, including Medicare payments.

Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes and the assigned relative value units exist for some patient-related activities (telephone consults, chronic care coordination, transitional care, telephone calls with patients) and may help value some activities. However, these should not limit the discussion of the value added by the neurologist.

There should be sufficient information about how costs of evaluation and treatment are assigned to the neurologist, to the PCP, or if it is a shared cost within the PCMH. Specifically, if the costs of evaluation and treatment are supported by guidelines, the authors propose no penalty associated with costs assigned to the neurologist. For example, certain neurogenetic disorders treated with enzyme replacement therapy should not be judged as part of the economic evaluation of physician performance. The outpatient pharmacy costs involved in the management of neurologic disorders such as multiple sclerosis are expensive, and could include not only immunomodulatory therapy but also botulinum toxin. Individual financial units would need to develop their own models for developing formularies and therapeutic flow charts based on best possible evidence, while also dealing with cost assignment for these expensive therapies.

Predictability in compensation should be the rule, and a range of choices consistent with neurologists' priorities regarding medical practice should be offered.

There should be a process for evaluating and planning value mapping of major diseases and treatment. The costs of treating migraine headache, for example, can vary 100-fold and therefore a transparent process for choosing therapies must be available to the patients, administration, and providers in the organization.

In non-fee-for-service models of care, such as ACOs, the role and necessity for CPT-based level of service for evaluation and management documentation should be defined. Although no physician should rely entirely on the prior evaluation of other providers, nor fail to provide comprehensive communication with the requesting physician, it should be clear that it is the PCP's role to have performed and documented a comprehensive history, including family history, social history, and medical history, a complete general physical examination, along with a current problem list and medication record. The physicians collaborating on the care of a patient must arrive at an agreement about which role the specialist will take (e.g., “consultation only” or an invitation to comanage the patient). Finally, although all providers have the responsibility to maintain accurate records in the EHR by providing updated edits to the allergy list, problem list, and listing/reconciliation of medications, the PCP will be in charge of reviewing and editing these lists for accuracy.

Quality measurement and improvement will be key components of the neurologist's participation in the PCMH process. The AAN is building robust guideline-based quality measures, and it is reasonable to agree that adherence will give positive credit to the physician. The costs associated with these quality measures should not be counted against the specialist. Neurologists should be given ongoing feedback about their use of approved quality measures.

The medical-legal implications and documentation standards must be defined in this new model that relies heavily on shared clinical information through EHRs, computer-aided decision support, and other innovations.

Neurologists have worked effectively with PCPs and other specialists under academic, fee-for-service, preferred provider organization, and health maintenance organization models. The new initiatives change the financial paradigm for the legacy establishments (e.g., hospitals, university groups, independent group practices, and individual practices), with newer models of reimbursement requiring a new and unprecedented level of communication and cooperation among all members of the team. The PCMH model is still under evaluation with pilot projects. PCMH has been more expensive than traditional care in prior pilot studies. As practice settings begin to adopt this model, neurologists will benefit from information regarding their role as a neighbor or as a primary provider for neurologic patients. The AAN should serve as a resource to its members, providing clinical vignettes and objective data regarding patient volume and compensation in this new setting. Communication between members and the AAN can serve to build a database that will assist specialty societies in compiling and organizing this valuable information.

The AAN and other specialty groups will begin to provide the necessary data to neurologists so that the risks and responsibilities of new models in which specialists are contracting can be readily understood. The AAN will also endeavor to set standards for the necessary information regarding these arrangements.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Bruce Sigsbee, MD, FAAN (President, AAN); Marc Raphaelson, MD; Laura Powers, MD, FAAN; Allison Weathers, MD; and members of the Medical Economics & Management Committee of the AAN for review of the manuscript and comments.

STUDY FUNDING

No targeted funding reported.

DISCLOSURES

D. Hoch has received honoraria for teaching at AAN courses and his wife owns stock in Express Scripts Holding Co., a medical services company. M. Homonoff and H. Moawad report no disclosures. B. Cohen has received honoraria for teaching at AAN courses, is a consultant to Health and Human Services for the Vaccine Compensation Program, receives travel funds for organizing clinical trials from Edison Pharmaceuticals, and has been on the speaker's bureau for Transgenomic (ending 12/31/2010). G. Esper has received honoraria for teaching at AAN courses and remuneration for legal consultation with Maglio, Christopher, and Toales Law firm. A. Becker is a full-time employee of the AAN. N. Busis has received honoraria for teaching at AAN courses. Go to Neurology.org/cp for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Emanuel E, Pearson S. Physician autonomy and health care reform. JAMA 2012;307:4–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.PCMH Defining the PCMH. Available at: http://www.pcmh.ahrq.gov/portal/server.pt/community/pcmh__home/1483/pcmh_defining_the_pcmh_v2. Accessed October 6, 2013

- 3.Nielsen M, Langner B, Zema C, Hacker T, Grundy P. Benefits of implementing the primary care patient-centered medical home: a review of cost and quality results, 2012. 2012:1–44 Available at: http://www.healthtransformation.ohio.gov/LinkClick.aspx?fileticket=CPQoPjxO47Q%3D&tabid=114. Accessed October 6, 2012.

- 4.American College of Physicians The Patient-Centered Medical Home Neighbor: The Interface of the Patient-Centered Medical Home with Specialty/Subspecialty Practices. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frakt AB, Mayes R. Beyond capitation: how new payment experiments seek to find the “sweet spot” in amount of risk providers and payers bear. Health Aff 2012;31:1951–1958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]