Abstract

Bartonella spp. and Brucella spp. are closely related α-proteobacterial pathogens that by distinct stealth-attack strategies cause chronic infections in mammals including humans. Human infections manifest by a broad spectrum of clinical symptoms, ranging from mild to fatal disease. Both pathogens establish intracellular replication niches and subvert diverse pathways of the host’s immune system. Several virulence factors allow them to adhere to, invade, proliferate, and persist within various host-cell types. In particular, type IV secretion systems (T4SS) represent essential virulence factors that transfer effector proteins tailored to recruit host components and modulate cellular processes to the benefit of the bacterial intruders. This article puts the remarkable features of these two pathogens into perspective, highlighting the mechanisms they use to hijack signaling and trafficking pathways of the host as the basis for their stealthy infection strategies.

Via analogous mechanisms, Bartonella and Brucella invade cells using (1) cell-surface molecules that mediate host–pathogen interactions, and (2) type IV secretion systems that produce effectors to manipulate host cells.

Bartonella spp. and Brucella spp. are Gram-negative facultative intracellular bacteria causing bartonellosis and brucellosis, respectively. These infections are typically chronic, ranging from subclinical courses to progressively debilitating and possibly life-threatening diseases. With a few exceptions in the genus Bartonella where the host reservoir is human, Bartonella spp. and Brucella spp. are zoonotic pathogens transmitted from mammals to humans. Wild animals are an important reservoir for the multiple species of both pathogenic genera. However, cats represent the major source for human infection by Bartonella (Breitschwerdt and Kordick 2000), whereas human infections by Brucella typically originate from livestock (Pappas et al. 2006). Therefore, individuals handling animals or infected material have a higher risk of getting infected either through direct contact or by aerosols. For Brucella, persons consuming infested animal products, often milk and its derivatives, are also at risk of getting infected (Pappas et al. 2006).

Via remarkably analogous mechanisms (Batut et al. 2004), Bartonella and Brucella invade various cell types using (1) cell-surface molecules that mediate host–pathogen interactions, such as adhesion proteins and receptors from the bacterial and host side, respectively; and (2) type IV secretion systems (T4SS) that translocate bacterial proteins termed effectors (Backert and Meyer 2006; Llosa et al. 2009). Importantly, effectors subvert intracellular trafficking and both innate and acquired immune responses (Roop et al. 2009; Harms and Dehio 2012; von Bargen et al. 2012), thus maneuvering host processes in favor of the pathogen.

BARTONELLA AND BRUCELLA: CLOSELY RELATED PATHOGENS WITH DISTINCT INFECTION SEQUELS

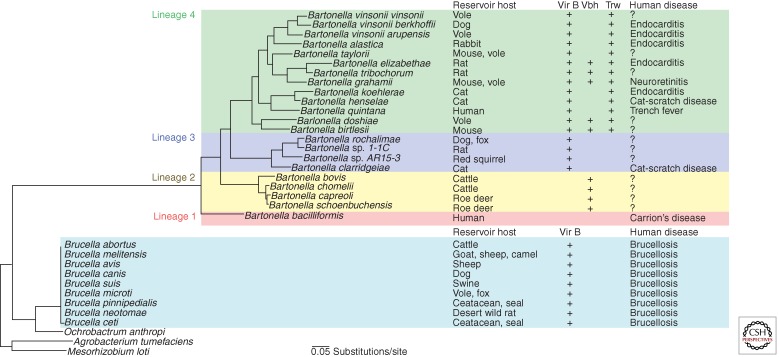

Bartonella spp. and Brucella spp. evolved from a common ancestor and belong to the Rhizobiales order of the α-proteobacteria (Gillespie et al. 2011), which includes microbes that coevolved with animal or plant hosts either as pathogens or as symbionts (Fig. 1). The Bartonella genus is composed of 24 species sharing a core genome and subdivided based on phylogenomic analysis in four phylogenetic lineages, lineage 1 being the most ancestral lineage with Bartonella bacilliformis as sole species (Saenz et al. 2007; Engel and Dehio 2009; Engel et al. 2011). The Brucella genus includes 10 species defined according to their preferential host (Moreno et al. 2002) and divided, based on phylogenomic analysis, in four clades: Brucella abortus–Brucella melitensis, Brucella suis–Brucella canis, Brucella ovis, and Brucella ceti (Wattam et al. 2009), with Brucella ovis being a potential common ancestor (Foster et al. 2009).

Figure 1.

Phylogeny, T4SS, and epidemiology of Bartonella and Brucella. At least one type IV secretion system (T4SS; VirB, Vbh, and Trw) is present in all Bartonella species except for Bartonella bacilliformis. A related VirB T4SS is also present in Brucella.

Each species of the genera Bartonella or Brucella infects one or few closely related mammals as reservoir host(s) wherein they persist and elicit diverse infection outcomes (Fig. 1). B. bacilliformis and Bartonella quintana are an exception in having humans as the reservoir host (Maguina et al. 2009). In their mammalian reservoir hosts, Bartonella spp. typically cause an intraerythrocytic bacteremia with an often asymptomatic course (Chomel et al. 2009), whereas Brucella provoke animal brucellosis, a chronic infection characterized by abortion probably due to the infection of trophoblasts, infertility, or birth of weak infected offspring (Hignett et al. 1966; Samartino and Enright 1993). Animal brucellosis is a significant economic burden in the endemic regions that span from central Asia to South America through the Middle East and the Mediterranean region (Pappas et al. 2006; Roop et al. 2009). Transmission of Bartonella is mediated by blood-sucking (hematophagous) arthropod vectors (Billeter et al. 2008; Tsai et al. 2011), whereas for Brucella, transmission is direct between mammals via contact with bacteria-rich material (Moreno and Moriyon 2006).

The epidemiology of Bartonella and Brucella infections as well as the interaction of these bacteria with and persistence within specific host cells suggest some host specificity that determines the selective incidence in certain mammals (Dehio and Sander 1999; Breitschwerdt and Kordick 2000; Tsolis 2002). This host specificity is governed by the intraerythrocytic persistence and the prevalence and ecology of the hematophagous vectors for Bartonella (Harms and Dehio 2012) and possibly by effectors translocated via the T4SS and distinctive gene sets localized to islands acquired by phage-mediated integration for Brucella (Paulsen et al. 2002; Andersson and Kempf 2004; de Jong and Tsolis 2012). When incidentally transmitted to humans, Bartonella and Brucella cause chronic infections that are frequently misdiagnosed, misreported, and therefore underestimated (Schwartzman 1996; Velho et al. 2003; Pappas et al. 2006).

Human bartonellosis ranges from the benign self-limiting manifestation of cat scratch disease (CSD) caused by infection with Bartonella henselae and possibly Bartonella clarridgeiae (Kordick et al. 1997), to a devastating hemolytic anemia caused by B. bacilliformis. B. henselae spreads in the feline reservoir by cat fleas (Ctenocephalides felis) (Chomel et al. 1996) and is transmitted to humans probably via inoculation of contaminated flea feces during a cat scratch or bite (Chomel et al. 2009). Symptoms of CSD are mainly lymphadenopathy (lymph node swelling) and occasionally fatigue and fever (Lamps and Scott 2004). B. quintana causes trench fever, a disease with persistent bacteremia that spreads under poor hygiene conditions by body lice (Pediculus humanus corporis) and occasionally by cat fleas (Rolain et al. 2003). The symptoms are a 5-d cyclic fever, bone pain, and headache (Byam and Lloyd 1920; Ohl and Spach 2000). A sequel of CSD and trench fever is bacillary angiomatosis: an outgrowth of vasoproliferative tumors affecting mainly the skin but also the liver (bacillary peliosis), spleen, bone marrow, eyes, or other organs and leading to extraerythrocytic bacteremia, neuroretinitis, infective endocarditis, and various neurological symptoms such as encephalitis (Maguina et al. 2009). B. bacilliformis, which is endemic in the Andes, where the natives show persistent asymptomatic bacteremia and might thus serve as a reservoir for infection (Ricketts 1948), is transmitted by the sand fly (Lutzomyia verrucarum), and is the sole Bartonella pathogen eliciting a biphasic life-threatening illness called Carrion’s disease. During the acute phase of this disease, which is termed Oroya fever and is rarely developed by the natives of the endemic regions, B. bacilliformis can infect a majority of the erythrocytes (Maguina et al. 2001), triggering a hemolytic anemia attributable to the hemophagocytosis of the infected erythrocytes by mononuclear phagocytes in spleen, lymph nodes, and liver (Walker and Winkler 1981; Maguina et al. 2009). This results in fever, hepatosplenomegaly (enlargement of the liver and spleen), lymphadenopathy, anemia (Fisman 2000; Janka 2007), and ultimately fatal suffocation or septicemia killing more than 80% of the untreated invalids (Ricketts 1948; Maguina et al. 2009). The second, chronic phase of Carrion’s disease, called verruga peruana, is characterized by vasoproliferative skin lesions that clinically resemble bacillary angiomatosis caused by B. henselae and B. quintana (Maguina et al. 2009).

Human brucellosis or Malta fever is a neglected, debilitating, relapsing, and often travel-related febrile disease. It is endemic in several regions where animal brucellosis is prevalent and is estimated to be the major bacterial zoonosis worldwide. Malta fever is demanding to treat with antibiotics, and there are no vaccines for humans that prevent infection (Memish and Balkhy 2004; Young 2005; Pappas et al. 2006; Ariza et al. 2007; Pappas 2010). It is transmitted by contact with infected animals, most often goats, sheep, or camels infected with B. melitensis, cattle infected with B. abortus, or swine infected with B. suis. In rare cases, marine mammals infected with Brucella pinnipedialis or B. ceti (Sohn et al. 2003; Foster et al. 2007; Whatmore et al. 2008), dogs infected with B. canis, desert wood rats infected with Brucella neotomae, and sheep infected with B. ovis are carriers (Corbel 1997). Brucella inopinata, isolated from brucellosis and chronic pneumonia patients (Scholz et al. 2010; Tiller et al. 2010), and Brucella microti, isolated from vole and foxes (Scholz et al. 2008), are recently uncovered strains whose transmission to humans is unclear. Symptoms of the acute phase of human brucellosis are flu-like periodic fevers with muscle and joint pain followed by lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and development of granulomas at multiple sites of the body (Franco et al. 2007a). Common complications, some of which are fatal if not promptly diagnosed and treated, are arthritis, liver abscess formation, neurobrucellosis, endocarditis, and even abortion in the endemic regions (Khan et al. 2001; Young 2005; Franco et al. 2007b).

BARTONELLA AND BRUCELLA: HOMOLOGOUS VIRULENCE SYSTEMS FOR SNEAKY HOST-CELL INVASION

Bartonella and Brucella encode conserved virulence factors that are essential for host-cell invasion as shown by in vitro and in vivo studies (Table 1). These include the VirB T4SS and adhesion molecules.

Table 1.

Virulence factors of Bartonella and Brucella

| Bartonella | Brucella | |

|---|---|---|

| T4SSs | ||

| VirB | Confined to lineages 3 and 4: VirB2–VirB11 and coupling protein VirD4 Essential for infection |

VirB1–VirB12 Essential for infection |

| Vbh | Confined to lineage 2 Putative role in infection |

— |

| Trw | Confined to lineage 4 Mediates erythrocyte invasion Essential for persistence |

— |

| VirB T4SS effectors | ||

| Beps: inhibit apoptosis; promote angiogenesis; promote invasome formation in B. henselae | Btp1: modulates microtubules’ dynamics and TLR4-mediated signaling CstA: interacts with Sec24A PrpA: elicits T-cell-independent IL-10 secretion RicA: interacts with Rab2-GDP BPE005, BPE123, BPE275, BPE043, BvfA, VceA, VceC, BPE043, BPE152: unclear function |

|

| Regulatory systems | ||

| Two-component regulatory systems (TC systems) | BatR/BatS Regulate essential gene transcription (i.e., virB) |

BvrR/BvrS Regulate essential gene transcription (i.e., virB) |

| Quorum-sensing systems | — | VjbR/BlxR Regulate numerous genes (i.e., vceA, vceC) |

| Adhesion molecules | ||

| Flagella | Confined to lineages 1–3 Mediate motility, erythrocytes’ adhesion and invasion Escape recognition by TLR5 |

Act as T3SS? Essential for virulence |

| Trimeric autotransporters | BadA, Vomps Essential for infection |

BtaE Essential for infection |

| Hemin-binding proteins | Hbp Essential for growth |

OMP25/31 |

| LPS | ||

| Lipid A | Pentaacylated with long fatty acid side chain Inhibits TLR4 proinflammatory response and promotes interaction with DCs |

Heptaacylated with long fatty acid side chain Inhibits TLR4 proinflammatory response |

| Core-polysaccharide | Uncharacterized function(s) | Inhibits complement activation and DC’s maturation |

| O-polysaccharide | Uncharacterized function(s) | Inhibits T-cell activation |

Machineries Indispensable for Host Interactions

VirB Type IV Secretion Systems: Master Virulence Factors

VirB T4SS are central virulence factors dictating the success of infection. The VirB T4SS of Bartonella species (lineages 3 and 4) and Brucella species are related but distinct in their subunit composition: VirB2–VirB11 and VirB1–VirB12, respectively. They bridge the bacterial inner membrane, periplasm, and outer membrane and extend into extracellular pili. This multiprotein complex functions as a translocation pore through which effector proteins are transferred into host cells, possibly by a piston mechanism (O’Callaghan et al. 1999; Sieira et al. 2000; Cascales and Christie 2003; Hwang and Gelvin 2004; Christie et al. 2005; Schroder and Dehio 2005; Zygmunt et al. 2006; Saenz et al. 2007; Wallden et al. 2010; Engel et al. 2011; de Jong and Tsolis 2012). As a canonical T4SS, the Bartonella VirB system comprises an effector-recognition component: the coupling protein VirD4 (Schroder and Dehio 2005), which has no homolog in Brucella, and which instead expresses the unique VirB12 (O’Callaghan et al. 1999). The genes of the VirB T4SSs are encoded as operons (Berger and Christie 1994), which either locate together with effector genes (Bartonella lineage 4) or not (Bartonella lineage 3 and Brucella) (Schulein et al. 2005; Engel et al. 2011; de Jong and Tsolis 2012).

Because biosynthesis of the multiprotein VirB T4SS and its translocated effectors is costly for the bacterial cells, expression is tightly regulated on the transcriptional level. For instance, in B. henselae, the virB operon and the genes encoding the coupling protein and the translocated effectors are maximally induced at physiological pH (Quebatte et al. 2010), whereas the virB operon expression in virulent Brucella strains is maximally induced in acidic milieus reminiscent of the lumen of Brucella-containing vacuoles (BCVs) (Boschiroli et al. 2002; Rouot et al. 2003).

The well-studied family of bacterial two-component regulatory systems (TC) is composed of pairs of a histidine kinase and an interacting response regulator. The surface-exposed histidine kinase becomes autophosphorylated upon sensing of an extracellular stimulus. The phosphate group is subsequently transferred to the response regulator, which, in turn, triggers transcriptional changes (Casino et al. 2010). The VirB T4SS of Bartonella and Brucella are transcriptionally controlled by homologous TCs, that is, BatR/BatS in Bartonella is most active at pH7.4 (Quebatte et al. 2010), and BvrR/BvrS in Brucella is most active at low pH (Martinez-Nunez et al. 2010; Viadas et al. 2010; Lacerda et al. 2013).

In Brucella, the loci encoding the VirB T4SS and other virulence factors like flagella and outer membrane proteins are controlled by additional regulatory systems such as the quorum-sensing LuxR-type regulators VjbR and BlxR, the starvation-sensing stringent response regulator Rsh (RelA/SpoT homolog), and small regulatory RNAs (sRNA) (Roop et al. 2009; von Bargen et al. 2012).

The VirB-translocated Bartonella effector proteins (Bep; named BepA–BepG in B. henselae) display a composite domain architecture characterized by an amino-terminal effector domain and a carboxy-terminal secretion signal (Schmid et al. 2004; Dehio 2005; Schulein et al. 2005; Engel et al. 2011). The carboxy-terminal secretion signal is bipartite and composed of a Bep intracellular delivery domain (BID) of approximately 140 amino acids and a short, nonconserved, positively charged tail sequence (Schulein et al. 2005). Besides mediating T4SS-dependent translocation into host cells, some BID domains can also directly modulate host-cellular pathways. For instance, the BID domain of BepA promotes apoptosis inhibition and angiogenesis (Schmid et al. 2006; Scheidegger et al. 2009). The amino-terminal effector domain is best exemplified by the FIC (filamentation induced by cyclic AMP) domain, which is present in some effectors of lineage 3 and most effectors of lineage 4 (Engel et al. 2011). This domain mediates AMPylation, the covalent transfer on an adenyl monophosphate (AMP) moiety onto the hydroxyl side chains of host target proteins like the small GTPases of the Rho family (Palanivelu et al. 2011; Engel et al. 2012). Effectors lacking an FIC domain show duplicated BID domains and/or amino-terminal tyrosine motifs that get phosphorylated inside host cells by Src family kinase(s) (Schulein et al. 2005; Selbach et al. 2009).

The few described putative Brucella effectors have unclear functions and only one common feature: a nonconserved carboxy-terminal positively charged amino acid sequence considered essential for VirB T4SS-dependent translocation (von Bargen et al. 2012). Examples are (1) VceA and VceC, which belong to the VjbR regulon, consequently having their expression coregulated with the VirB T4SS (de Jong et al. 2008); (2) BPE123, whose translocation additionally depends on a Sec-secretion signal at the amino terminus; and (3) BPE005, BPE275, and BPE043 (Table 1) (Marchesini et al. 2011). Other putative effectors with indefinite positively charged amino acid carboxy-terminal sequences are (1) RicA, which is the sole effector having an assigned host partner, the guanosine diphosphate (GDP)-bound form of the small GTPase Rab2 (de Barsy et al. 2011); (2) Btp1 (TcpB in B. melitensis), which regulates innate immune responses via its Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain (Cirl et al. 2008; Salcedo et al. 2008) and possibly modulates microtubule dynamics (Radhakrishnan et al. 2011); (3) PrpA, a proline-racemase family member, which regulates immune responses (Spera et al. 2006); (4) CstA (conserved Sec24A-targeted protein A), which controls Brucella intracellular trafficking (de Barsy et al. 2012); and (5) BvfA, which is required for Brucella intracellular replication (Lavigne et al. 2005).

Instead of the VirB T4SS, some Bartonella species encode a VirB homologous (Vbh) T4SS (Fig. 1) (Dehio 2008). Vbh was likely the first T4SS acquired by the Bartonella lineage and is present in all species of lineage 2. It is believed to have been functionally replaced within lineages 3 and 4 by the subsequently acquired VirB T4SS (some lineage 4 species still encode nonfunctional remnants of Vbh) (Fig. 1). Vbh components display protein sequence identity of 40%–80% with their VirB homologs, suggesting that the two systems have only recently diverged from a common ancestor (Saenz et al. 2007). Further to the Vbh system, the vbh locus encodes a putative effector protein with the canonical FIC–BID architecture of the VirB-translocated Beps, advocating a potential role in virulence (Engel et al. 2011).

Adhesion Molecules: Key for Host–Pathogen Interaction

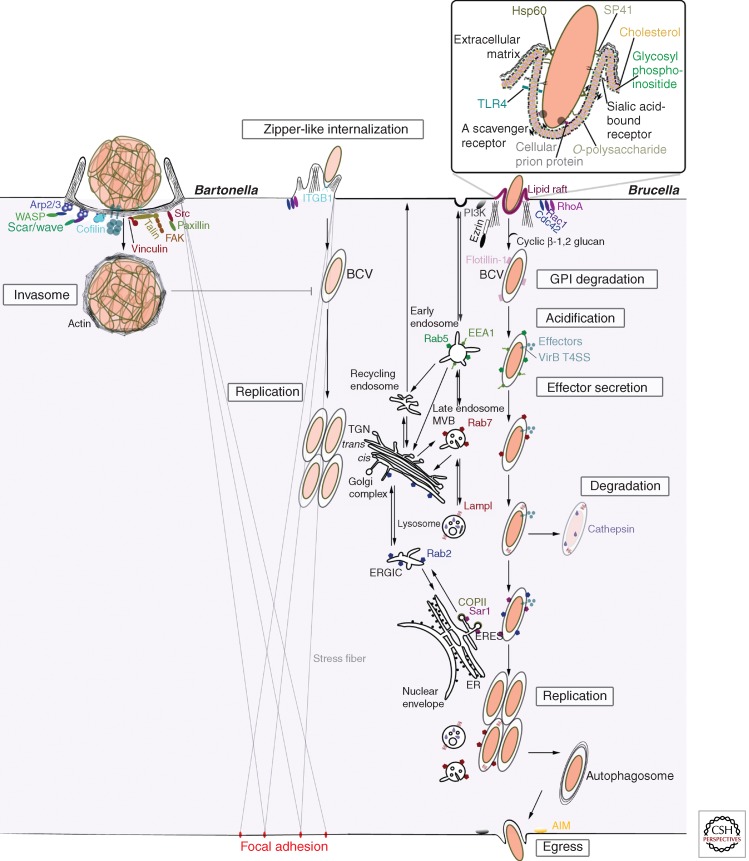

Adhesion molecules are often multifunctional membrane-exposed proteins and complexes necessary for Bartonella attachment to host cells (O'Rourke et al. 2011). Homologs of some of these adhesins are also present in Brucella, although their function is less scrutinized (von Bargen et al. 2012). They interact with host extracellular matrix (ECM) components (e.g., fibronectin, collagen) and receptors (e.g., integrins for Bartonella and sialic acid–bound receptors for Brucella) (Fig. 2). Such molecules include the Trw T4SS (for Bartonella), flagella, autotransporter adhesins, the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) systems, the hemin-binding proteins, and further outer membrane proteins (OMP) such as in Bartonella OMP89 and OMP43, a homolog of Brucella OMP2b (Dabo et al. 2006).

Figure 2.

Intracellular life of Bartonella and Brucella. Bartonella and Brucella invade cells in vacuolar structures (BCV) or, in the case of B. henselae, as an aggregate in invasomes. Once internalized, these structures interact with specific host components and compartments subverting their function. AIM, Autophagy initiation markers; COPII, coatomer protein II; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ERGIC, ER–Golgi intermediate compartment; ERES, ER exit sites; MVB, multivesicular bodies; T4SS, type IV secretion system.

Trw T4SS

Trw is a T4SS that functionally diversified to an adhesion complex crucial for persistence of all Bartonella lineage 4 species (Schroder and Dehio 2005). The trw locus comprises an operon encoding a typical T4SS but as a particularity displays multiple tandem-repeated gene copies encoding variant forms of the extracellular pilus component. The Bartonella Trw T4SS is closely related to the canonical Trw conjugation system of the conjugative plasmid R388 and was thus probably gained by horizontal gene transfer (Seubert et al. 2003). The Trw T4SS mediates erythrocyte adhesion of lineage 4 species in a host-specific manner. The subsequent invasion process requires the invasion-associated locus, containing IalA and IalB, and/or the IalAB-independent erythrocyte invasion locus, Iiv (Seubert et al. 2003; Dehio 2004; Schroder and Dehio 2005; Saenz et al. 2007; Vayssier-Taussat et al. 2010; Deng et al. 2012).

Flagella

Flagella are bacterial nanomachines that mediate motility. The filament of flagella that is composed of a single protein, flagellin, is assembled by the basal body by a pathway homologous to the type 3 secretion system (T3SS) (Hueck 1998; Kirov 2003). In motile Bartonella species (lineages 1–3, except Bartonella bovis), flagella are considered to mediate erythrocyte internalization as a mechanical force or as adhesion molecules, as shown exemplarily for B. bacilliformis (Walker and Winkler 1981; Mernaugh and Ihler 1992). Bartonella species of lineage 4 that are nonmotile owing to the loss of flagella do mediate erythrocyte interaction via the Trw T4SS, which suggests that Trw has functionally replaced flagella for establishing interaction with erythrocytes (Dehio 2008). Brucella are nonmotile bacteria, yet flagella genes are essential for their virulence (Lestrate et al. 2003). Debatably, the basal body may function as a T3SS rather than establishing a motile nanomachine (Fretin et al. 2005).

Autotransporter Adhesins

This family mediates adhesion to nucleated cells and interactions with ECM, belongs to the type 5 secretion system (T5SS), and comprises two-partner systems (TPSs), classical monomeric autotransporter adhesins (CAAs), and trimeric autotransporter adhesins (TAAs). TPS filamentous haemagglutinins in Bartonella are putative adhesins encoded by multiple genes, indicating functional redundancy (O’Rourke et al. 2011). CAAs and TAAs are characterized by an amino-terminal signal peptide, a passenger domain, and a carboxy-terminal translocation domain (van Ulsen 2011). CAAs important for infection are in Brucella are OmaA (outer membrane autotransporter A) (Bandara et al. 2005) and BmaC (Posadas et al. 2012), and in Bartonella are Arp (acidic repeat protein) (Litwin et al. 2007) and Cfa (cAMP-like factor autotransporter) (Litwin and Johnson 2005), two members of the Iba (inducible Bartonella autotransporter) group whose expression is induced during infection. TAAs are essential for virulence and have a head–stalk–anchor structure forming modular length–adaptable trimerized cell surface-exposed filaments (Linke et al. 2006). Examples are BtaE in Brucella (Ruiz-Ranwez et al. 2013) and in Bartonella, B. henselae adhesin A (BadA) and the homologous B. quintana variably expressed outer membrane proteins (Vomps) (Zhang et al. 2004; Muller et al. 2011). Bartonella TAAs additionally induce angiogenesis and serum resistance (O’Rourke et al. 2011). Interestingly, BadA expression on the bacterial surface masks the activity of the VirB T4SS (Lu et al. 2013), but these two major virulence factors are differentially regulated on the transcriptional level via the TC system BatS/BatR, indicating that the two act at different stages of the infection process.

ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter Systems

ABC transporters are a family of transport systems that hydrolyze adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Davidson and Chen 2004; Davidson et al. 2008). Examples are the heme HutABC/HmuV (Parrow et al. 2009) and iron FatBCD and Sit/YfeABCd (Battisti et al. 2006) uptake systems as well as the ugp-encoded glycerol 3-phosphate importers (Saenz et al. 2007) in Bartonella. Such an importer is in Brucella surface protein 41 (SP41), which probably interacts with sialylated host receptors (Castaneda-Roldan et al. 2006).

Hemin-Binding Proteins

Hemin-binding proteins (Hbps in Bartonella and OMP25/31 in Brucella) constitute a family of porin-like outer membrane proteins that bind hemin (Battisti et al. 2006; Dabo et al. 2006; Delpino et al. 2006; Caro-Hernandez et al. 2007). Hemin is essential for Bartonella growth (Sander et al. 2000), rendering these bacteria the most hemin-dependent microbes.

Strategies for Host Invasion

Lessons Learned from In Vitro Studies

Our understating of cellular invasion processes during Bartonella and Brucella infections is greatly based on in vitro infection models. These comprise primary cells and immortalized cell lines: professional phagocytes (e.g., macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells), nonprofessional phagocytic cells (e.g., epithelial cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells), erythrocytes for Bartonella, and trophoblasts for Brucella (Anderson et al. 1986; Benson et al. 1986; Kordick and Breitschwerdt 1995; Roop et al. 2009; Harms and Dehio 2012; von Bargen et al. 2012; Salcedo et al. 2013). Entry into cells leads to the establishment of BCVs (Bartonella/Brucella-containing vacuoles), structures formed when Bartonella and Brucella are taken up as single bacteria or as small bacterial clumps (Moreno and Gorvel 2004; Eicher and Dehio 2012). Some Bartonella species additionally enter host cells in aggregates of hundreds of bacteria, leading to the establishment of an invasion structure known as the invasome (Fig. 2) (Dehio et al. 1997).

Uptake into BCVs or Invasomes: Alternative Routes of Bacterial Entry Exemplified by B. henselae

At early stages of B. henselae interaction with host cells (also at subsequent stages in the case of VirB-T4SS deficiency), individual bacteria trigger a zipper-like entry mechanism involving Rho, Rac, Cdc42, tyrosine phosphorylation, and/or α5β1-integrin (Fig. 2) (Hill et al. 1992; Brouqui and Raoult 1996; Williams-Bouyer and Hill 1999; Truttmann et al. 2011a). Once internalized, BCVs induce focal adhesion-anchored stress fibers and possibly replicate in the juxtanuclear region, where they presumably interact with the Golgi apparatus (Kempf et al. 2000; Verma et al. 2000, 2001; Verma and Ihler 2002; Kyme et al. 2005).

Once the VirB T4SS-translocated effectors reach a critical intracellular concentration, the formation of BCVs by individual bacterial uptake is blocked. Bacteria then accumulate on the cell surface, which is followed by bacterial aggregation by host-cell-driven surface transport, and subsequent internalization into a structure termed the invasome. This unique bacterial uptake structure is reminiscent of bacterial aggregates in bacillary angiomatosis lesions (Dehio et al. 1997; Dehio 2003). Invasome formation is triggered by VirB-translocated effectors via redundant pathways, which depend on either BepG or the combination of BepC and BepF. In each case, this results in the formation of a compact F-actin ring composed of condensed stress fibers, and membrane protrusions on the host-cell surface (Fig. 2) (Rhomberg et al. 2009; Truttmann et al. 2011b). This process is dependent on integrin-β1 (ITGB1) binding and activation via Talin-1 inside-out signaling and on integrin-β1-mediated outside-in signaling by focal adhesion kinase (FAK), Src, vinculin, and paxilin (Truttmann et al. 2011b). Invasome rearrangement of the F-actin cytoskeleton involves Arp2/3-dependent cortical F-actin polymerization by Rac1/Scar1/WAVE, Cdc42/WASP pathways, and additionally by cofilin-1 in the case of BepC and BepF (Rhomberg et al. 2009; Truttmann et al. 2011b,c).

Uptake of Brucella in BCVs

Contrary to Bartonella, the VirB T4SS of Brucella is not expressed during bacterial uptake and thus does not contribute to this process. Entry is mediated by surface-exposed bacterial and host membrane complexes at cholesterol- and glycosylphosphoinositide (GPI)-rich host-cell membrane domains (lipid rafts) (Pizarro-Cerda et al. 1998; Watarai et al. 2002, 2003; Kim et al. 2004; Nakato et al. 2012) in a phosphoinositide (PI)-3 kinase, actin, ezrin, Rho, Rac, Cdc42, and/or Toll-like receptor (TLR)4-dependent manner (Fig. 2) (Guzman-Verri et al. 2001; Chaves-Olarte et al. 2002; Watanabe et al. 2009). Once inside cells, BCVs’ lipid raft organization is disrupted by the bacterial membrane periplasm-enriched Brucella virulence factor β-1,2 cyclic glucan, which promotes acidification and development of autophagosome properties (Pizarro-Cerda et al. 1998; Ugalde 1999; Arenas et al. 2000; Arellano-Reynoso et al. 2005; Starr et al. 2008). Acidification requires the recruitment of early endosome (Rab5, EEA1), late endosome (Rab7), and lysosome (Lamp1) markers, and is necessary for the activation of virulence factors such as virB genes (Porte et al. 1999; Boschiroli et al. 2002) essential for interactions with early secretory pathway components (Sar1/Sec24A/COPII, Rab2, and its partners) and endoplasmic reticulum-derived ribosome-rich structures (Comerci et al. 2001; Celli et al. 2003, 2005; Fugier et al. 2009) where Brucella replicate and persist before egressing in an autophagy initiation molecules and PI3 kinase-dependent manner (Roop et al. 2009; Starr et al. 2012).

Uptake in Erythrocytes: A Route to Persistence

A hallmark of Bartonella infection is invasion of erythrocytes using the Trw T4SS or flagella as adhesion factors (Harms and Dehio 2012). These processes depend on host-cell-surface glycosyl moieties, actin, spectrin, band 3 protein, glycophorin A, and/or glycophorin B (Walker and Winkler 1981; Iwaki-Egawa and Ihler 1997; Buckles and McGinnis Hill 2000; Chomel et al. 2009; Vayssier-Taussat et al. 2010; Deng et al. 2012). A potential amphiphilic small molecule, deformin, deforms the erythrocytes’ membrane initiating “forced endocytosis” of Bartonella in vacuoles, where they shortly replicate but persist (Benson et al. 1986; Iwaki-Egawa and Ihler 1997; Derrick and Ihler 2001).

Lessons Learned from In Vivo Studies

Bartonella and Brucella infection spreads from the site of inoculation to distinct immune-privileged persistence niches that are essential for transmission to other hosts. During dissemination to the persistence niches, these pathogens may colonize other host niches. The identities of the primary niches remain elusive, although dendritic cells, and in the case of Bartonella also endothelial cells, have been proposed to represent such primary niches (Harms and Dehio 2012; von Bargen et al. 2012). The persistence niches are erythrocytes for Bartonella (Schulein and Dehio 2002) and the reticuloendothelial system for Brucella (Ficht 2003). Dissecting the sequence of events from the primary to the persistence niches is fundamental to understand the progression from an acute infection to a chronic disease. For this, clinical data and mostly laboratory in vivo models, in which different infection stages can be monitored, are essential. A widely used Brucella in vivo model is mouse, which largely recapitulates natural animal brucellosis (Silva et al. 2011). Several Bartonella species also have a small animal model reflecting infection either (1) in the reservoir host (Fig. 1), for example, rat for Bartonella tribocorum (Schulein and Dehio 2002) and mouse for Bartonella birtlesii and Bartonella grahamii (Koesling et al. 2001; Marignac et al. 2010); or (2) in a nonreservoir host as an incidental infection, for example, the lymphadenopathy mouse model for B. henselae (Kunz et al. 2008), mirroring human infection by zoonotic species (in this case, CSD). In vivo models also proved to be a significant tool in understanding immune responses during the course of infection.

BARTONELLA AND BRUCELLA: ANALOGOUS VIRULENCE FACTORS FOR DIVERSE APPROACHES TO MODULATE IMMUNE RESPONSES

Bartonella and Brucella possess conserved virulence factors essential for chronic infection. These include LPS and for some species flagella, which promote survival for longer periods in macrophages, interfere with dendritic cell (DC) maturation, and modulate immunity (Kohler et al. 2003; Roop et al. 2004; Dehio et al. 2012).

LPS Modifications: Proficiency to Escape Immune Responses

Lipopolysaccharides (LPSs) are conserved sheaths of Gram-negative bacteria composed of an endotoxin component lipid moiety (lipid A) that provides membrane anchoring, a core, and an extracellular polysaccharide chain (O-polysaccharide). They are pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP), eliciting an immune response. However, Bartonella and Brucella LPSs have unique structural modifications that fail to display endotoxin activity (Table 1) (Moreno et al. 1981; Rasool et al. 1992; Matera et al. 2008). Similar chemical modifications aiming at detoxifying LPSs and thus dampening the immune response are used by other Gram-negative bacteria such as Helicobacter pylori (Miller et al. 2005).

Bartonella and Brucella lipid A structure is characterized by a short glycosyl backbone (diaminoglucose), a pentaacylation for Bartonella and a heptaacylation for Brucella, as well as a very long fatty acid side chain (Iriarte et al. 2004; Zahringer et al. 2004; Lapaque et al. 2006; Matera et al. 2008). This lipid A is poorly recognized by TLR4, thereby impeding a broad inflammatory response (Miller et al. 2005). B. quintana LPS is further a potent antagonist of TLR4 signaling (Popa et al. 2007).

Depending on the presence or absence of the O-polysaccharide, Brucella strains are, respectively, smooth human-infective or rough (Haag et al. 2010). Brucella O-polysaccharide inhibits T-cell activation, probably via sequestration of MHCII in large macrodomains in infected macrophages (Moreno et al. 1981; Forestier et al. 1999, 2000; Barquero-Calvo et al. 2007).

Brucella core polysaccharide inhibits DC maturation, TLR4–MD2 recognition, and complement activation, thus complement-mediated bacterial lysis (Conde-Alvarez et al. 2012). DC maturation is also inhibited by the Brucella T4SS effector Btp1, which, owing to its TIR domain, mimics host TLR signaling, specifically dampening TLR2 and TLR4 signaling and subsequent NF-κB activation. The Btp1 TIR domain mediates interaction with the death domain of Myd88 (myeloid differentiation factor 88) and/or TIRAP/MAL (TIR-associated protein), leading to TIRAP/MAL ubiquitination, then degradation (Cirl et al. 2008; Salcedo et al. 2008; Radhakrishnan et al. 2009; Sengupta et al. 2010; Chaudhary et al. 2012). Conversely, the glucose polymer β1,2-cyclic glucan activates DC in a TLR4 Myd88-dependent manner, thus counteracting Btp1-mediated inhibition of DC maturation (Martirosyan et al. 2012). Whether Bartonella has a similar DC maturation fine-tuning as Brucella is unclear, but Bartonella is hitherto known to stimulate DC maturation in a TLR2-dependent manner (Vermi et al. 2006; Pulliainen and Dehio 2012).

Flagellin Mutations: Adeptness to Escape Immune Responses

The conserved amino-terminal D1 domain of flagellin that mediates flagella assembly is also detected by TLR5, thereby triggering proinflammatory responses (Ramos et al. 2004). However, the flagellated Bartonella species and also a few other pathogens like H. pylori fail to elicit such immune responses thanks to amino acid changes in the D1 domain that dampen recognition by TLR5 and subsequent NF-κB activation. These flagellin mutations can interfere with flagella function and thus are always associated with compensatory mutations that preserve motility (Andersen-Nissen et al. 2005).

Additional Strategies to Subvert Immune Responses

Besides manipulating DC maturation and consequently T-cell-mediated immune responses, Bartonella and Brucella can also control T-cell-independent immune responses. For instance, the Brucella effector PrpA elicits T-cell-independent B-lymphocyte polyclonal activation and anti-inflammatory IL-10 cytokine secretion (Spera et al. 2006), which is also induced by an unknown Bartonella component (Matera et al. 2003, 2008). It is thus likely that both Bartonella and Brucella induce a transient and partial immune suppression to establish chronic infection (Couper et al. 2008; Harms and Dehio 2012).

Immune suppression is apparently also required for vasoproliferative tumor-like lesion formation during bacillary angiomatosis, a clinical manifestation caused by B. henselae or B. quintana infection in immunocompromised patients (Maguina et al. 2009). These lesions are characterized by small vessels lined with endothelial cells and are an amalgam of bacteria, polymorphonuclear neutrophils, macrophages, and endothelial cells, the latter two being effective producers of angiogenic factors (Cotell and Noskin 1994; Kostianovsky and Greco 1994; Manders 1996; Qian and Pollard 2010). In these lesions, Bartonella induces (1) autocrine angiogenesis in an angiopoetin-2, IL-8, ICAM-1, and/or Bcl-2-related protein A1-dependent manner (Cerimele et al. 2003; McCord et al. 2006); and/or (2) a VirB T4SS-dependent or -independent paracrine angiogenic loop, thus stimulating the secretion of the potent angiogenic stimulus, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Kempf et al. 2001; Resto-Ruiz et al. 2002; Schulte et al. 2006). The VirB T4SS-dependent angiogenesis in B. henselae is the net effect of pro- and antiangiogenic activities of BepA/BepD and BepG, respectively (Scheidegger et al. 2009). In a Gαs-dependent manner, BepA binds adenylyl cyclase, consequently elevating cAMP levels and probably inhibiting NF-κB-dependent caspase activation and DNA fragmentation, two hallmarks of apoptosis (Kirby and Nekorchuk 2002; Schmid et al. 2006; Pulliainen et al. 2012). Similar to Bartonella, apoptosis suppression is a characteristic feature of Brucella infection. It is T4SS- and LPS-dependent and the result of (1) transcriptional regulation of pro- and antiapoptotic genes such as bcl-2 family A1 and caspase-3, and (2) inhibition of mitochondrial cytochrome c release and reactive oxygen species, thus dampening caspase activation (Gross et al. 2000; Eskra et al. 2003; Tolomeo et al. 2003; He et al. 2006).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Pathogens of the closely related α-proteobacterial genera Bartonella and Brucella encode, on the one hand, homologous virulence devices and factors (i.e., VirB T4SS, LPS) and, on the other hand, specific effectors and strategies to invade, proliferate, and persist into host cells and organisms and thus engender distinctive chronic, occasionally fatal infections. Further investigation of virulence factors, deciphering their functions, and elucidating the host interaction partners and mechanisms involved in vitro and in vivo as well as in the global context of infection will be crucial to unveil the causes and processes of the persisting zoonosis. Such a goal requires concerted approaches that integrate basic sciences, veterinary sciences, and clinical medicine. This endeavor would improve diagnostics and therapeutics in animals and humans, allow the generation of animal and human vaccines, and eventually minimize outbreaks and eradicate the disease in the sporadic and endemic regions, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. Philipp Engel for providing the phylogenetic tree of Figure 1. This study is supported by grant 31003A-132979 from the Swiss National Sciences Foundation and grant 51RT-0-126008 from SystemX.ch (to C.D.) and by The Fondation Recherche Médicale, FRM (to J.-P.G.).

Footnotes

Editors: Pascale Cossart and Stanley Maloy

Additional Perspectives on Bacterial Pathogenesis available at www.perspectivesinmedicine.org

REFERENCES

- Andersen-Nissen E, Smith KD, Strobe KL, Barrett SL, Cookson BT, Logan SM, Aderem A 2005. Evasion of Toll-like receptor 5 by flagellated bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 9247–9252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson TD, Meador VP, Cheville NF 1986. Pathogenesis of placentitis in the goat inoculated with Brucella abortus. I. Gross and histologic lesions. Vet Pathol 23: 219–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson SG, Kempf VA 2004. Host cell modulation by human, animal and plant pathogens. Int J Med Microbiol 293: 463–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arellano-Reynoso B, Lapaque N, Salcedo S, Briones G, Ciocchini AE, Ugalde R, Moreno E, Moriyon I, Gorvel JP 2005. Cyclic β-1,2-glucan is a Brucella virulence factor required for intracellular survival. Nat Immunol 6: 618–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arenas GN, Staskevich AS, Aballay A, Mayorga LS 2000. Intracellular trafficking of Brucella abortus in J774 macrophages. Infect Immun 68: 4255–4263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariza J, Bosilkovski M, Cascio A, Colmenero JD, Corbel MJ, Falagas ME, Memish ZA, Roushan MR, Rubinstein E, Sipsas NV, et al. 2007. Perspectives for the treatment of brucellosis in the 21st century: The Ioannina recommendations. PLoS Med 4: e317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backert S, Meyer TF 2006. Type IV secretion systems and their effectors in bacterial pathogenesis. Curr Opin Microbiol 9: 207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandara AB, Sriranganathan N, Schurig GG, Boyle SM 2005. Putative outer membrane autotransporter protein influences survival of Brucella suis in BALB/c mice. Vet Microbiol 109: 95–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barquero-Calvo E, Chaves-Olarte E, Weiss DS, Guzman-Verri C, Chacon-Diaz C, Rucavado A, Moriyon I, Moreno E 2007. Brucella abortus uses a stealthy strategy to avoid activation of the innate immune system during the onset of infection. PLoS ONE 2: e631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battisti JM, Sappington KN, Smitherman LS, Parrow NL, Minnick MF 2006. Environmental signals generate a differential and coordinated expression of the heme receptor gene family of Bartonella quintana. Infect Immun 74: 3251–3261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batut J, Andersson SG, O’Callaghan D 2004. The evolution of chronic infection strategies in the α-proteobacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 2: 933–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson LA, Kar S, McLaughlin G, Ihler GM 1986. Entry of Bartonella bacilliformis into erythrocytes. Infect Immun 54: 347–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger BR, Christie PJ 1994. Genetic complementation analysis of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens virB operon: virB2 through virB11 are essential virulence genes. J Bacteriol 176: 3646–3660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billeter SA, Levy MG, Chomel BB, Breitschwerdt EB 2008. Vector transmission of Bartonella species with emphasis on the potential for tick transmission. Med Vet Entomol 22: 1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschiroli ML, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Foulongne V, Michaux-Charachon S, Bourg G, Allardet-Servent A, Cazevieille C, Liautard JP, Ramuz M, O’Callaghan D 2002. The Brucella suis virB operon is induced intracellularly in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 1544–1549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitschwerdt EB, Kordick DL 2000. Bartonella infection in animals: Carriership, reservoir potential, pathogenicity, and zoonotic potential for human infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 13: 428–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouqui P, Raoult D 1996. Bartonella quintana invades and multiplies within endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo and forms intracellular blebs. Res Microbiol 147: 719–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckles EL, McGinnis Hill E 2000. Interaction of Bartonella bacilliformis with human erythrocyte membrane proteins. Microb Pathog 29: 165–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byam W, Lloyd L 1920. Trench fever: Its epidemiology and endemiology. Proc R Soc Med 13: 1–27 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caro-Hernandez P, Fernandez-Lago L, de Miguel MJ, Martin-Martin AI, Cloeckaert A, Grillo MJ, Vizcaino N 2007. Role of the Omp25/Omp31 family in outer membrane properties and virulence of Brucella ovis. Infect Immun 75: 4050–4061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cascales E, Christie PJ 2003. The versatile bacterial type IV secretion systems. Nat Rev Microbiol 1: 137–149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casino P, Rubio V, Marina A 2010. The mechanism of signal transduction by two-component systems. Curr Opin Struct Biol 20: 763–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaneda-Roldan EI, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Saldana Z, Avelino F, Rendon MA, Dornand J, Giron JA 2006. Characterization of SP41, a surface protein of Brucella associated with adherence and invasion of host epithelial cells. Cell Microbiol 8: 1877–1887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli J, de Chastellier C, Franchini DM, Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Gorvel JP 2003. Brucella evades macrophage killing via VirB-dependent sustained interactions with the endoplasmic reticulum. J Exp Med 198: 545–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli J, Salcedo SP, Gorvel JP 2005. Brucella coopts the small GTPase Sar1 for intracellular replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 1673–1678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerimele F, Brown LF, Bravo F, Ihler GM, Kouadio P, Arbiser JL 2003. Infectious angiogenesis: Bartonella bacilliformis infection results in endothelial production of angiopoetin-2 and epidermal production of vascular endothelial growth factor. Am J Pathol 163: 1321–1327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary A, Ganguly K, Cabantous S, Waldo GS, Micheva-Viteva SN, Nag K, Hlavacek WS, Tung CS 2012. The Brucella TIR-like protein TcpB interacts with the death domain of MyD88. Biochem Biophys Res Com 417: 299–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaves-Olarte E, Guzman-Verri C, Meresse S, Desjardins M, Pizarro-Cerda J, Badilla J, Gorvel JP, Moreno E 2002. Activation of Rho and Rab GTPases dissociates Brucella abortus internalization from intracellular trafficking. Cell Microbiol 4: 663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomel BB, Kasten RW, Floyd-Hawkins K, Chi B, Yamamoto K, Roberts-Wilson J, Gurfield AN, Abbott RC, Pedersen NC, Koehler JE 1996. Experimental transmission of Bartonella henselae by the cat flea. J Clin Microbiol 34: 1952–1956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomel BB, Boulouis HJ, Breitschwerdt EB, Kasten RW, Vayssier-Taussat M, Birtles RJ, Koehler JE, Dehio C 2009. Ecological fitness and strategies of adaptation of Bartonella species to their hosts and vectors. Vet Res 40: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie PJ, Atmakuri K, Krishnamoorthy V, Jakubowski S, Cascales E 2005. Biogenesis, architecture, and function of bacterial type IV secretion systems. Annu Rev Microbiol 59: 451–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirl C, Wieser A, Yadav M, Duerr S, Schubert S, Fischer H, Stappert D, Wantia N, Rodriguez N, Wagner H, et al. 2008. Subversion of Toll-like receptor signaling by a unique family of bacterial Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing proteins. Nat Med 14: 399–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comerci DJ, Martinez-Lorenzo MJ, Sieira R, Gorvel JP, Ugalde RA 2001. Essential role of the VirB machinery in the maturation of the Brucella abortus–containing vacuole. Cell Microbiol 3: 159–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conde-Alvarez R, Arce-Gorvel V, Iriarte M, Mancek-Keber M, Barquero-Calvo E, Palacios-Chaves L, Chacon-Diaz C, Chaves-Olarte E, Martirosyan A, von Bargen K, et al. 2012. The lipopolysaccharide core of Brucella abortus acts as a shield against innate immunity recognition. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbel MJ 1997. Brucellosis: An overview. Emerg Infect Dis 3: 213–221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotell SL, Noskin GA 1994. Bacillary angiomatosis. Clinical and histologic features, diagnosis, and treatment. Arch Intern Med 154: 524–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couper KN, Blount DG, Riley EM 2008. IL-10: The master regulator of immunity to infection. J Immunol 180: 5771–5777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabo SM, Confer AW, Saliki JT, Anderson BE 2006. Binding of Bartonella henselae to extracellular molecules: Identification of potential adhesins. Microb Pathog 41: 10–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson AL, Chen J 2004. ATP-binding cassette transporters in bacteria. Annu Rev Biochem 73: 241–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson AL, Dassa E, Orelle C, Chen J 2008. Structure, function, and evolution of bacterial ATP-binding cassette systems. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 72: 317–364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Barsy M, Jamet A, Filopon D, Nicolas C, Laloux G, Rual JF, Muller A, Twizere JC, Nkengfac B, Vandenhaute J, et al. 2011. Identification of a Brucella spp. secreted effector specifically interacting with human small GTPase Rab2. Cell Microbiol 13: 1044–1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Barsy M, Mirabella A, Letesson JJ, De Bolle X 2012. A Brucella abortus cstA mutant is defective for association with endoplasmic reticulum exit sites and displays altered trafficking in HeLa cells. Microbiol 158: 2610–2618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehio C 2003. Recent progress in understanding Bartonella-induced vascular proliferation. Curr Opin Microbiol 6: 61–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehio C 2004. Molecular and cellular basis of Bartonella pathogenesis. Annu Rev Microbiol 58: 365–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehio C 2005. Bartonella–host-cell interactions and vascular tumour formation. Nat Rev Microbiol 3: 621–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehio C 2008. Infection-associated type IV secretion systems of Bartonella and their diverse roles in host cell interaction. Cell Microbiol 10: 1591–1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehio C, Sander A 1999. Bartonella as emerging pathogens. Trends Microbiol 7: 226–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehio C, Meyer M, Berger J, Schwarz H, Lanz C 1997. Interaction of Bartonella henselae with endothelial cells results in bacterial aggregation on the cell surface and the subsequent engulfment and internalisation of the bacterial aggregate by a unique structure, the invasome. J Cell Sci 110: 2141–2154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehio C, Berry C, Bartenschlager R 2012. Persistent intracellular pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev 36: 513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong MF, Tsolis RM 2012. Brucellosis and type IV secretion. Future Microbiol 7: 47–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong MF, Sun YH, den Hartigh AB, van Dijl JM, Tsolis RM 2008. Identification of VceA and VceC, two members of the VjbR regulon that are translocated into macrophages by the Brucella type IV secretion system. Mol Microbiol 70: 1378–1396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpino MV, Cassataro J, Fossati CA, Goldbaum FA, Baldi PC 2006. Brucella outer membrane protein Omp31 is a haemin-binding protein. Microbes Infect 8: 1203–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng HK, Le Rhun D, Le Naour E, Bonnet S, Vayssier-Taussat M 2012. Identification of Bartonella Trw host-specific receptor on erythrocytes. PLoS ONE 7: e41447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrick SC, Ihler GM 2001. Deformin, a substance found in Bartonella bacilliformis culture supernatants, is a small, hydrophobic molecule with an affinity for albumin. Blood Cells Mol Dis 27: 1013–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eicher SC, Dehio C 2012. Bartonella entry mechanisms into mammalian host cells. Cell Microbiol 14: 1166–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel P, Dehio C 2009. Genomics of host-restricted pathogens of the genus Bartonella. Genome Dyn 6: 158–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel P, Salzburger W, Liesch M, Chang CC, Maruyama S, Lanz C, Calteau A, Lajus A, Medigue C, Schuster SC, et al. 2011. Parallel evolution of a type IV secretion system in radiating lineages of the host-restricted bacterial pathogen Bartonella. PLoS Genet 7: e1001296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel P, Goepfert A, Stanger FV, Harms A, Schmidt A, Schirmer T, Dehio C 2012. Adenylylation control by intra- or intermolecular active-site obstruction in Fic proteins. Nature 482: 107–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskra L, Mathison A, Splitter G 2003. Microarray analysis of mRNA levels from RAW264.7 macrophages infected with Brucella abortus. Infect Immun 71: 1125–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficht TA 2003. Intracellular survival of Brucella: Defining the link with persistence. Vet Microbiol 92: 213–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisman DN 2000. Hemophagocytic syndromes and infection. Emerg Infect Dis 6: 601–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forestier C, Moreno E, Meresse S, Phalipon A, Olive D, Sansonetti P, Gorvel JP 1999. Interaction of Brucella abortus lipopolysaccharide with major histocompatibility complex class II molecules in B lymphocytes. Infect Immun 67: 4048–4054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forestier C, Deleuil F, Lapaque N, Moreno E, Gorvel JP 2000. Brucella abortus lipopolysaccharide in murine peritoneal macrophages acts as a down-regulator of T cell activation. J Immunol 165: 5202–5210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster G, Osterman BS, Godfroid J, Jacques I, Cloeckaert A 2007. Brucella ceti sp. nov. and Brucella pinnipedialis sp. nov. for Brucella strains with cetaceans and seals as their preferred hosts. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 57: 2688–2693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster JT, Beckstrom-Sternberg SM, Pearson T, Beckstrom-Sternberg JS, Chain PS, Roberto FF, Hnath J, Brettin T, Keim P 2009. Whole-genome-based phylogeny and divergence of the genus Brucella. J Bacteriol 191: 2864–2870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco MP, Mulder M, Gilman RH, Smits HL 2007a. Human brucellosis. Lancet Infect Dis 7: 775–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco MP, Mulder M, Smits HL 2007b. Persistence and relapse in brucellosis and need for improved treatment. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 101: 854–855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fretin D, Fauconnier A, Kohler S, Halling S, Leonard S, Nijskens C, Ferooz J, Lestrate P, Delrue RM, Danese I, et al. 2005. The sheathed flagellum of Brucella melitensis is involved in persistence in a murine model of infection. Cell Microbiol 7: 687–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugier E, Salcedo SP, de Chastellier C, Pophillat M, Muller A, Arce-Gorvel V, Fourquet P, Gorvel JP 2009. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and the small GTPase Rab 2 are crucial for Brucella replication. PLoS Pathog 5: e1000487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie JJ, Wattam AR, Cammer SA, Gabbard JL, Shukla MP, Dalay O, Driscoll T, Hix D, Mane SP, Mao C, et al. 2011. PATRIC: The comprehensive bacterial bioinformatics resource with a focus on human pathogenic species. Infect Immun 79: 4286–4298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross A, Terraza A, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Liautard JP, Dornand J 2000. In vitro Brucella suis infection prevents the programmed cell death of human monocytic cells. Infect Immun 68: 342–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman-Verri C, Chaves-Olarte E, von Eichel-Streiber C, Lopez-Goni I, Thelestam M, Arvidson S, Gorvel JP, Moreno E 2001. GTPases of the Rho subfamily are required for Brucella abortus internalization in nonprofessional phagocytes: Direct activation of Cdc42. J Biol Chem 276: 44435–44443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haag AF, Myka KK, Arnold MF, Caro-Hernandez P, Ferguson GP 2010. Importance of lipopolysaccharide and cyclic β-1,2-glucans in Brucella-mammalian infections. Int J Microbiol 2010: 124509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms A, Dehio C 2012. Intruders below the radar: Molecular pathogenesis of Bartonella spp. Clin Microbiol Rev 25: 42–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Reichow S, Ramamoorthy S, Ding X, Lathigra R, Craig JC, Sobral BW, Schurig GG, Sriranganathan N, Boyle SM 2006. Brucella melitensis triggers time-dependent modulation of apoptosis and down-regulation of mitochondrion-associated gene expression in mouse macrophages. Infect Immun 74: 5035–5046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hignett PG, Nagy LK, Ironside CJ 1966. Bovine brucellosis: A study of an adult-vaccinated, Brucella-infected herd. I. The effect of Brucella abortus infection on fertility. Vet Rec 79: 886–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill EM, Raji A, Valenzuela MS, Garcia F, Hoover R 1992. Adhesion to and invasion of cultured human cells by Bartonella bacilliformis. Infect Immun 60: 4051–4058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueck CJ 1998. Type III protein secretion systems in bacterial pathogens of animals and plants. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 62: 379–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang HH, Gelvin SB 2004. Plant proteins that interact with VirB2, the Agrobacterium tumefaciens pilin protein, mediate plant transformation. Plant Cell 16: 3148–3167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iriarte M, Gonzalez D, Delrue RM, Monreal D, Conde R, Lopez-Goni I, Letesson JJ, Moriyon I 2004. Brucella lipopolysaccharide: Structure, biosynthesis and genetics. In Brucella: Molecular and cellular biology (ed. Lopez-Goni I, Moriyon I), pp. 152–183 Horizon Bioscience, Norwich, UK [Google Scholar]

- Iwaki-Egawa S, Ihler GM 1997. Comparison of the abilities of proteins from Bartonella bacilliformis and Bartonella henselae to deform red cell membranes and to bind to red cell ghost proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett 157: 207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janka GE 2007. Hemophagocytic syndromes. Blood Rev 21: 245–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempf VA, Schaller M, Behrendt S, Volkmann B, Aepfelbacher M, Cakman I, Autenrieth IB 2000. Interaction of Bartonella henselae with endothelial cells results in rapid bacterial rRNA synthesis and replication. Cell Microbiol 2: 431–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempf VA, Volkmann B, Schaller M, Sander CA, Alitalo K, Riess T, Autenrieth IB 2001. Evidence of a leading role for VEGF in Bartonella henselae–induced endothelial cell proliferations. Cell Microbiol 3: 623–632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MY, Mah MW, Memish ZA 2001. Brucellosis in pregnant women. Clin Infect Dis 32: 1172–1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Watarai M, Suzuki H, Makino S, Kodama T, Shirahata T 2004. Lipid raft microdomains mediate class A scavenger receptor-dependent infection of Brucella abortus. Microb Pathog 37: 11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby JE, Nekorchuk DM 2002. Bartonella-associated endothelial proliferation depends on inhibition of apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 4656–4661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirov SM 2003. Bacteria that express lateral flagella enable dissection of the multifunctional roles of flagella in pathogenesis. FEMS Microbiol Lett 224: 151–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koesling J, Aebischer T, Falch C, Schulein R, Dehio C 2001. Cutting edge: Antibody-mediated cessation of hemotropic infection by the intraerythrocytic mouse pathogen Bartonella grahamii. J Immunol 167: 11–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler S, Michaux-Charachon S, Porte F, Ramuz M, Liautard JP 2003. What is the nature of the replicative niche of a stealthy bug named Brucella? Trends Microbiol 11: 215–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordick DL, Breitschwerdt EB 1995. Intraerythrocytic presence of Bartonella henselae. J Clin Microbiol 33: 1655–1656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordick DL, Hilyard EJ, Hadfield TL, Wilson KH, Steigerwalt AG, Brenner DJ, Breitschwerdt EB 1997. Bartonella clarridgeiae, a newly recognized zoonotic pathogen causing inoculation papules, fever, and lymphadenopathy (cat scratch disease). J Clin Microbiol 35: 1813–1818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostianovsky M, Greco MA 1994. Angiogenic process in bacillary angiomatosis. Ultrastruct Pathol 18: 349–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz S, Oberle K, Sander A, Bogdan C, Schleicher U 2008. Lymphadenopathy in a novel mouse model of Bartonella-induced cat scratch disease results from lymphocyte immigration and proliferation and is regulated by interferon-α/β. Am J Pathol 172: 1005–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyme PA, Haas A, Schaller M, Peschel A, Iredell J, Kempf VA 2005. Unusual trafficking pattern of Bartonella henselae–containing vacuoles in macrophages and endothelial cells. Cell Microbiol 7: 1019–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacerda TL, Salcedo SP, Gorvel JP 2013. Brucella T4SS: The VIP pass inside host cells. Curr Opin Microbiol 16: 45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamps LW, Scott MA 2004. Cat-scratch disease: Historic, clinical, and pathologic perspectives. Am J Clin Pathol 121: S71–S80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapaque N, Forquet F, de Chastellier C, Mishal Z, Jolly G, Moreno E, Moriyon I, Heuser JE, He HT, Gorvel JP 2006. Characterization of Brucella abortus lipopolysaccharide macrodomains as mega rafts. Cell Microbiol 8: 197–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JP, Patey G, Sangari FJ, Bourg G, Ramuz M, O’Callaghan D, Michaux-Charachon S 2005. Identification of a new virulence factor, BvfA, in Brucella suis. Infect Immun 73: 5524–5529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lestrate P, Dricot A, Delrue RM, Lambert C, Martinelli V, De Bolle X, Letesson JJ, Tibor A 2003. Attenuated signature-tagged mutagenesis mutants of Brucella melitensis identified during the acute phase of infection in mice. Infect Immun 71: 7053–7060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke D, Riess T, Autenrieth IB, Lupas A, Kempf VA 2006. Trimeric autotransporter adhesins: Variable structure, common function. Trends Microbiol 14: 264–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin CM, Johnson JM 2005. Identification, cloning, and expression of the CAMP-like factor autotransporter gene (Cfa) of Bartonella henselae. Infect Immun 73: 4205–4213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litwin CM, Rawlins ML, Swenson EM 2007. Characterization of an immunogenic outer membrane autotransporter protein, Arp, of Bartonella henselae. Infect Immun 75: 5255–5263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llosa M, Roy C, Dehio C 2009. Bacterial type IV secretion systems in human disease. Mol Microbiol 73: 141–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu YY, Franz B, Truttmann MC, Riess T, Gay-Fraret J, Faustmann M, Kempf VA, Dehio C 2013. Bartonella henselae trimeric autotransporter adhesin BadA expression interferes with effector translocation by the VirB/D4 type IV secretion system. Cell Microbiol 15: 759–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguina C, Garcia PJ, Gotuzzo E, Cordero L, Spach DH 2001. Bartonellosis (Carrion’s disease) in the modern era. Clin Infect Dis 33: 772–779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguina C, Guerra H, Ventosilla P 2009. Bartonellosis. Clin Dermatol 27: 271–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manders SM 1996. Bacillary angiomatosis. Clin Dermatol 14: 295–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesini MI, Herrmann CK, Salcedo SP, Gorvel JP, Comerci DJ 2011. In search of Brucella abortus type IV secretion substrates: Screening and identification of four proteins translocated into host cells through VirB system. Cell Microbiol 13: 1261–1274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marignac G, Barrat F, Chomel B, Vayssier-Taussat M, Gandoin C, Bouillin C, Boulouis HJ 2010. Murine model for Bartonella birtlesii infection: New aspects. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 33: 95–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Nunez C, Altamirano-Silva P, Alvarado-Guillen F, Moreno E, Guzman-Verri C, Chaves-Olarte E 2010. The two-component system BvrR/BvrS regulates the expression of the type IV secretion system VirB in Brucella abortus. J Bacteriol 192: 5603–5608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martirosyan A, Perez-Gutierrez C, Banchereau R, Dutartre H, Lecine P, Dullaers M, Mello M, Pinto Salcedo S, Muller A, Leserman L, et al. 2012. Brucella β 1,2 cyclic glucan is an activator of human and mouse dendritic cells. PLoS Pathog 8: e1002983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matera G, Liberto MC, Quirino A, Barreca GS, Lamberti AG, Iannone M, Mancuso E, Palma E, Cufari FA, Rotiroti D, et al. 2003. Bartonella quintana lipopolysaccharide effects on leukocytes, CXC chemokines and apoptosis: A study on the human whole blood and a rat model. Int Immunopharmacol 3: 853–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matera G, Liberto MC, Joosten LA, Vinci M, Quirino A, Pulicari MC, Kullberg BJ, Van der Meer JW, Netea MG, Foca A 2008. The Janus face of Bartonella quintana recognition by Toll-like receptors (TLRs): A review. Eur Cytokine Netw 19: 113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCord AM, Resto-Ruiz SI, Anderson BE 2006. Autocrine role for interleukin-8 in Bartonella henselae-induced angiogenesis. Infect Immun 74: 5185–5190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memish ZA, Balkhy HH 2004. Brucellosis and international travel. J Travel Med 11: 49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mernaugh G, Ihler GM 1992. Deformation factor: An extracellular protein synthesized by Bartonella bacilliformis that deforms erythrocyte membranes. Infect Immun 60: 937–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller SI, Ernst RK, Bader MW 2005. LPS, TLR4 and infectious disease diversity. Nat Rev Microbiol 3: 36–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno E, Gorvel JP 2004. Invasion, intracellular trafficking and replication of Brucella organisms in professional and nonprofessional phagocytes. In Brucella: Molecular and cellular biology (ed. Moriyon I, Lopez-Goni I), pp. 287–312 Horizon Bioscience, Norwich, UK [Google Scholar]

- Moreno E, Moriyon I 2006. The genus Brucella. In Prokaryotes: A handbook on the biology of bacteria, 3rd ed. (ed. Dworkin M, et al. ), Vol. 5, pp. 315–456 Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- Moreno E, Speth SL, Jones LM, Berman DT 1981. Immunochemical characterization of Brucella lipopolysaccharides and polysaccharides. Infect Immun 31: 214–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno E, Cloeckaert A, Moriyon I 2002. Brucella evolution and taxonomy. Vet Microbiol 90: 209–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller NF, Kaiser PO, Linke D, Schwarz H, Riess T, Schafer A, Eble JA, Kempf VA 2011. Trimeric autotransporter adhesin-dependent adherence of Bartonella henselae, Bartonella quintana, and Yersinia enterocolitica to matrix components and endothelial cells under static and dynamic flow conditions. Infect Immun 79: 2544–2553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakato G, Hase K, Suzuki M, Kimura M, Ato M, Hanazato M, Tobiume M, Horiuchi M, Atarashi R, Nishida N, et al. 2012. Cutting edge: Brucella abortus exploits a cellular prion protein on intestinal M cells as an invasive receptor. J Immunol 189: 1540–1544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Callaghan D, Cazevieille C, Allardet-Servent A, Boschiroli ML, Bourg G, Foulongne V, Frutos P, Kulakov Y, Ramuz M 1999. A homologue of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB and Bordetella pertussis Ptl type IV secretion systems is essential for intracellular survival of Brucella suis. Mol Microbiol 33: 1210–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohl ME, Spach DH 2000. Bartonella quintana and urban trench fever. Clin Infect Dis 31: 131–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke F, Schmidgen T, Kaiser PO, Linke D, Kempf VA 2011. Adhesins of Bartonella spp. Adv Exp Med Biol 715: 51–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanivelu DV, Goepfert A, Meury M, Guye P, Dehio C, Schirmer T 2011. Fic domain-catalyzed adenylylation: Insight provided by the structural analysis of the type IV secretion system effector BepA. Prot Sci 20: 492–499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas G 2010. The changing Brucella ecology: Novel reservoirs, new threats. Int J Antimicrob Agents 36: S8–S11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas G, Papadimitriou P, Akritidis N, Christou L, Tsianos EV 2006. The new global map of human brucellosis. Lancet Infect Dis 6: 91–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrow NL, Abbott J, Lockwood AR, Battisti JM, Minnick MF 2009. Function, regulation, and transcriptional organization of the hemin utilization locus of Bartonella quintana. Infect Immun 77: 307–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulsen IT, Seshadri R, Nelson KE, Eisen JA, Heidelberg JF, Read TD, Dodson RJ, Umayam L, Brinkac LM, Beanan MJ, et al. 2002. The Brucella suis genome reveals fundamental similarities between animal and plant pathogens and symbionts. Proc Natl Acad Sci 99: 13148–13153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro-Cerda J, Meresse S, Parton RG, van der Goot G, Sola-Landa A, Lopez-Goni I, Moreno E, Gorvel JP 1998. Brucella abortus transits through the autophagic pathway and replicates in the endoplasmic reticulum of nonprofessional phagocytes. Infect Immun 66: 5711–5724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa C, Abdollahi-Roodsaz S, Joosten LA, Takahashi N, Sprong T, Matera G, Liberto MC, Foca A, van Deuren M, Kullberg BJ, et al. 2007. Bartonella quintana lipopolysaccharide is a natural antagonist of Toll-like receptor 4. Infect Immun 75: 4831–4837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porte F, Liautard JP, Kohler S 1999. Early acidification of phagosomes containing Brucella suis is essential for intracellular survival in murine macrophages. Infect Immun 67: 4041–4047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posadas DM, Ruiz-Ranwez V, Bonomi HR, Martin FA, Zorreguieta A 2012. BmaC, a novel autotransporter of Brucella suis, is involved in bacterial adhesion to host cells. Cell Microbiol 14: 965–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulliainen AT, Dehio C 2012. Persistence of Bartonella spp. stealth pathogens: From subclinical infections to vasoproliferative tumor formation. FEMS Microbiol Rev 36: 563–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulliainen AT, Pieles K, Brand CS, Hauert B, Bohm A, Quebatte M, Wepf A, Gstaiger M, Aebersold R, Dessauer CW, et al. 2012. Bacterial effector binds host cell adenylyl cyclase to potentiate Gαs-dependent cAMP production. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109: 9581–9586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian BZ, Pollard JW 2010. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell 141: 39–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quebatte M, Dehio M, Tropel D, Basler A, Toller I, Raddatz G, Engel P, Huser S, Schein H, Lindroos HL, et al. 2010. The BatR/BatS two-component regulatory system controls the adaptive response of Bartonella henselae during human endothelial cell infection. J Bacteriol 192: 3352–3367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan GK, Yu Q, Harms JS, Splitter GA 2009. Brucella TIR domain-containing protein mimics properties of the Toll-like receptor adaptor protein TIRAP. J Biol Chem 284: 9892–9898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan GK, Harms JS, Splitter GA 2011. Modulation of microtubule dynamics by a TIR domain protein from the intracellular pathogen Brucella melitensis. Biochem J 439: 79–83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos HC, Rumbo M, Sirard JC 2004. Bacterial flagellins: Mediators of pathogenicity and host immune responses in mucosa. Trends Microbiol 12: 509–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasool O, Freer E, Moreno E, Jarstrand C 1992. Effect of Brucella abortus lipopolysaccharide on oxidative metabolism and lysozyme release by human neutrophils. Infect Immun 60: 1699–1702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resto-Ruiz SI, Schmiederer M, Sweger D, Newton C, Klein TW, Friedman H, Anderson BE 2002. Induction of a potential paracrine angiogenic loop between human THP-1 macrophages and human microvascular endothelial cells during Bartonella henselae infection. Infect Immun 70: 4564–4570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhomberg TA, Truttmann MC, Guye P, Ellner Y, Dehio C 2009. A translocated protein of Bartonella henselae interferes with endocytic uptake of individual bacteria and triggers uptake of large bacterial aggregates via the invasome. Cell Microbiol 11: 927–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts WE 1948. Bartonella bacilliformis anemia (Oroya fever): A study of 30 cases. Blood 3: 1025–1049 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolain JM, Franc M, Davoust B, Raoult D 2003. Molecular detection of Bartonella quintana, B. koehlerae, B. henselae, B. clarridgeiae, Rickettsia felis, and Wolbachia pipientis in cat fleas, France. Emerg Infect Dis 9: 338–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roop RM 2nd, Bellaire BH, Valderas MW, Cardelli JA 2004. Adaptation of the Brucellae to their intracellular niche. Mol Microbiol 52: 621–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roop RM 2nd, Gaines JM, Anderson ES, Caswell CC, Martin DW 2009. Survival of the fittest: How Brucella strains adapt to their intracellular niche in the host. Med Microbiol Immunol 198: 221–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouot B, Alvarez-Martinez MT, Marius C, Menanteau P, Guilloteau L, Boigegrain RA, Zumbihl R, O’Callaghan D, Domke N, Baron C 2003. Production of the type IV secretion system differs among Brucella species as revealed with VirB5- and VirB8-specific antisera. Infect Immun 71: 1075–1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Ranwez V, Posadas DM, Van der Henst C, Estein SM, Arocena GM, Abdian PL, Martin FA, Sieira R, De Bolle X, Zorreguieta A 2013. BtaE, an adhesin that belongs to the trimeric autotransporter family, is required for full virulence and defines a specific adhesive pole of Brucella. Infect Immun 81: 996–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saenz HL, Engel P, Stoeckli MC, Lanz C, Raddatz G, Vayssier-Taussat M, Birtles R, Schuster SC, Dehio C 2007. Genomic analysis of Bartonella identifies type IV secretion systems as host adaptability factors. Nat Genet 39: 1469–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo SP, Marchesini MI, Lelouard H, Fugier E, Jolly G, Balor S, Muller A, Lapaque N, Demaria O, Alexopoulou L, et al. 2008. Brucella control of dendritic cell maturation is dependent on the TIR-containing protein Btp1. PLoS Pathog 4: e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo SP, Chevrier N, Santos Lacerda TL, Ben Amara A, Gerart S, Gorvel VA, de Chastellier C, Blasco JM, Mege JL, Gorvel JP 2013. Pathogenic Brucellae replicate in human trophoblasts. J Infect Dis 207: 1075–1083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samartino LE, Enright FM 1993. Pathogenesis of abortion of bovine brucellosis. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 16: 95–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander A, Kretzer S, Bredt W, Oberle K, Bereswill S 2000. Hemin-dependent growth and hemin binding of Bartonella henselae. FEMS Microbiol Lett 189: 55–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidegger F, Ellner Y, Guye P, Rhomberg TA, Weber H, Augustin HG, Dehio C 2009. Distinct activities of Bartonella henselae type IV secretion effector proteins modulate capillary-like sprout formation. Cell Microbiol 11: 1088–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid MC, Schulein R, Dehio M, Denecker G, Carena I, Dehio C 2004. The VirB type IV secretion system of Bartonella henselae mediates invasion, proinflammatory activation and antiapoptotic protection of endothelial cells. Mol Microbiol 52: 81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid MC, Scheidegger F, Dehio M, Balmelle-Devaux N, Schulein R, Guye P, Chennakesava CS, Biedermann B, Dehio C 2006. A translocated bacterial protein protects vascular endothelial cells from apoptosis. PLoS Pathog 2: e115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz HC, Hubalek Z, Sedlacek I, Vergnaud G, Tomaso H, Al Dahouk S, Melzer F, Kampfer P, Neubauer H, Cloeckaert A, et al. 2008. Brucella microti sp nov, isolated from the common vole Microtus arvalis. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 58: 375–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholz HC, Nockler K, Gollner C, Bahn P, Vergnaud G, Tomaso H, Al Dahouk S, Kampfer P, Cloeckaert A, Maquart M, et al. 2010. Brucella inopinata sp nov, isolated from a breast implant infection. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 60: 801–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder G, Dehio C 2005. Virulence-associated type IV secretion systems of Bartonella. Trends Microbiol 13: 336–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulein R, Dehio C 2002. The VirB/VirD4 type IV secretion system of Bartonella is essential for establishing intraerythrocytic infection. Mol Microbiol 46: 1053–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulein R, Guye P, Rhomberg TA, Schmid MC, Schroder G, Vergunst AC, Carena I, Dehio C 2005. A bipartite signal mediates the transfer of type IV secretion substrates of Bartonella henselae into human cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 102: 856–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]