Abstract

The medical costs for a type 2 diabetes patient are two to four times greater than the costs for a patient without diabetes. Bariatric surgery is the most effective weight loss therapy and has marked therapeutic effects on diabetes. We estimate the economic effect of the clinical benefits of bariatric surgery for diabetes patients with BMI ≥35 kg/m.

Using an administrative claims database of privately insured patients covering 8.5 million lives 1999-2007, we identify obese patients with diabetes, aged 18-65, who were treated with bariatric surgery identified using HCPCS codes. These patients were matched with non-surgery control patients on demographic factors, comorbidities and healthcare costs. The overall return on investment (RoI) associated with bariatric surgery was calculated using multivariate analysis. Surgery and control patients were compared post-index with respect to diagnostic claims for diabetes, diabetes medication claims and adjusted diabetes medication and supply costs. Surgery costs were fully recovered after 26 months for laparoscopic surgery. At month 6, 28% of surgery patients had a diabetes diagnosis, compared to 74% of control patients (p<.001). Among pre-index insulin users, insulin use dropped to 43% by month 3 for surgery patients, versus 84% for controls (p<.001). By month 1, medication and supply costs were significantly lower for surgery patients (p<.001).

The therapeutic benefits of bariatric surgery on diabetes translate into considerable economic benefits. These data suggest that surgical therapy is clinically more effective and ultimately less expensive than standard therapy for diabetes patients with BMI ≥35 kg/m.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a major public health concern in the United States and elsewhere because of its prevalence, considerable morbidity and mortality, and economic burden. In 2007, the prevalence rate of diabetes in the US was 7.8%, affecting 12 million men and 11.5 million women (1). Diabetes is associated with serious complications, including coronary heart disease, kidney failure, neuropathy, blindness and amputation, and was the seventh leading cause of death in 2006, accounting for over 72,000 deaths (1). Type 2 diabetes accounts for 90-95% of all diagnosed cases (1).

Estimated yearly costs of managing a diabetes patient ($13,243) are more than five times that of a patient without diabetes ($2,560) (2). The estimated annual total economic cost of diabetes in the US was $174 billion in 2007 – $116 billion in medical expenditures and $58 billion in reduced productivity (2). The largest components of costs are hospital inpatient care (50%), medication and supplies (12%), retail prescriptions to treat complications (11%), and physician office visits (9%) (2). The annual cost has been projected to reach over $350 billion by 2025 and a cumulative $2.6 trillion over the next 30 years (2).

Obesity is a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes (3), and the risk of diabetes increases directly with BMI (4). Thus, increased prevalence of diabetes is related to the increased prevalence of obesity. In 2007-2008, one-third of US adults had BMI ≥30 kg/m2, and 5.7% were Class III (BMI ≥40 kg/m2) (5). Diabetes-related costs represent a disproportionate share of healthcare costs among the obese (6). Weight loss is an important therapeutic goal in obese patients with type 2 diabetes, because even moderate weight loss (5%) improves insulin sensitivity (7). Bariatric surgery is the most effective weight loss therapy and has considerable beneficial effects on diabetes and other obesity-related comorbidities (8,9,10). However, bariatric surgery requires a significant up-front expenditure.

The purpose of this study was to estimate the economic impact of the clinical benefits of bariatric surgery on medical costs and return on investment (RoI) of the surgery in diabetes patients with BMI ≥35 kg/m2.

Methods and Procedures

Data

We identified 808 diabetes patients who had bariatric surgery and a matched cohort of 808 diabetes patients who did not have surgery using an administrative claims database of privately insured patients covering 8.5 million lives from 1999 through 2007 at 40 large nationwide companies. This database contains deidentified patient medical and pharmacy claims, demographics, enrollment history, date of service, associated diagnoses, performed procedures, billed charges, and actual insurance payments. Pharmacy claims contain complete information on prescribed medications (date filled, days of supply, quantity and payment amount).

Bariatric surgery patients with diabetes were identified using the following criteria: 1) at least one bariatric surgery claim, identified using HCPCS codes 43644, 43645, 43770, 43842, 43843, 43845, 43846, 43847, S2082, S2083 and S2085; 2) at least one medical claim diagnosis of obesity for which BMI ≥35 kg/m2 (ICD-9– CM 278.01) any time before the index/surgery date; 3) continuous enrollment for at least 6 months before and one month after the index date; 4) 18 to 65 years old at the index date; and 5) diabetes diagnosis prior to the index date. Because the claims data do not record clinical outcomes that could be used to identify diabetes at baseline, such as glycosylated hemoglobin levels, we used the criteria outlined by Pladevall et al. (11), and defined patients as having diabetes (type 1 or 2) if, in the three months before the index date, the patient had both: i) one or more medical claims for diabetes (ICD-9-CM 250.xx), dyslipidemia (ICD-9-CM 272.xx) or hypertension (ICD-9-CM 401.xx-405.xx); and ii) one or more claims for diabetes medication.

Laparoscopic procedures were not recorded separately until 2004. On average, between 2004 and 2007, 30% of procedures were performed laparoscopically. By 2007, laparoscopic procedures constituted 44% of which nearly half were laparoscopic banding.

Matching procedure

One control patient with diabetes was matched with each bariatric surgery patient with diabetes on the following criteria: 1) age; 2) sex; 3) state of residence; 4) comorbidities (asthma, coronary artery disease, gallstones, gastroesophageal reflux, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, sleep apnea, and urinary incontinence); and 5) healthcare cumulative costs in months −6 to −2 before the index date within one standard deviation of the surgery patient's cumulative costs in the same period. Where more than one control could be matched with a surgery patient, one control patient was randomly selected.

Analysis

Data for surgery and their matched control patients were obtained for six months before and up to 36 months after surgery. We calculated overall RoI based on total direct medical costs and assessed three post-index/surgery outcome measures: 1) diagnostic claims for diabetes; 2) claims for diabetes medication; and 3) average total costs of diabetes medications and supplies.

Using the methodology in Cremieux et al. (12), we calculated RoI by comparing monthly costs for surgery and control patients over time. To avoid bias from imbalances across the two samples, the multivariate RoI analysis accounts for eight additional comorbidities (breast cancer, congestive heart failure, lymphedema, major depression, osteoarthritis, polycystic ovary syndrome, pseudotumor cerebri, and venous stasis/leg ulcers) based on existing literature and American Society for Bariatric Surgery guidelines (13). Total healthcare costs were deflated to 2007 dollars using the CPI for Medical Care, and incremental savings from surgery were discounted using the mean return on a 3-month Treasury bill, 3.43%.

The cost differential between surgery and control patients was calculated by estimating a cluster Tobit model on the pooled population (surgery and control patients) and using the coefficients on interacting bariatric surgery with the relevant time period. For surgery patients, the investment in bariatric surgery is the sum of all incremental claims incurred in the month before surgery, during surgery and two months after surgery relative to the claims of the control patients during the same period. RoI is calculated by offsetting the investment in bariatric surgery against the returns from incremental cost savings post-surgery.

The numbers of diabetes diagnoses and medication claims were calculated every three months post-surgery for 36 months. Claims for surgery and control patients were compared using chi-square tests. Monthly drug costs were calculated post-surgery for 36 months and adjusted by the CPI for Medical Care, and were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum tests.

All estimations were performed using statistical software Intercooled STATA 10 and SAS 9.2.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of study participants. The sample is predominantly female (72.8%), with a mean age of 51.5 for surgery and 52.3 for control patients. Breast cancer and major depression were the only two comorbidities with a statistically different prevalence across the two groups, and were among the eight comorbidities included as control variables in the multivariate RoI analysis. The two groups had similar baseline healthcare costs in months −6 to −2 prior to index date. Surgery patients had 28.7% higher baseline medical service costs while control patients had 36.2% higher prescription drug costs.

Table 1. Comorbidities and Medical Care Utilization Prior to Surgery Index Date.

| Baseline Characteristics | Surgery Patients (N=808) | Control Patients (N=808) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | ||

| Age on Index Date (Median [IQR]) | 53 (47-57) | 53 (47-59) |

| Female (%) | 72.8 | 72.8 |

| Matched Comorbidities (%) | ||

| Diabetes | 100 | 100 |

| Sleep Apnea | 21.7 | 21.7 |

| Coronary Artery Disease | 7.8 | 7.8 |

| Gastroesophageal Reflux | 6.6 | 6.6 |

| Asthma | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| Gall Stones | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| NASH/NAFLD | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Urinary Incontinence | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Other Comorbidities - Controlled for in Multivariate Analysis (%) | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 10.9 | 11.9 |

| Major Depression * | 9.3 | 5.1 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 3.5 | 4.0 |

| Lymphedema | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| Polycystic Ovary Syndrome | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| Breast Cancer* | 0.4 | 1.7 |

| Venous Stasis and Leg Ulcers | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| Pseudo Tumor Cerebri | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Health Care Utilization (%) | ||

| Inpatient Visit * | 23.1 | 8.5 |

| ER Visit * | 13.2 | 17.1 |

| Outpatient Hospital Visit * | 90.8 | 67.5 |

| Office Visit | 99.9 | 99.4 |

| Use of Medication for Weight Loss | 1.5 | 1.6 |

| Health Care Costs ($, median [IQR]) | ||

| Drug Costs * | 1,231 (680-2,005) | 1,450 (790-2,656) |

| Medical Costs * | 1,579 (585-3,422) | 878 (358-2,370) |

| Total Health Care Costs | 3,209 (1,828-5,192) | 2,842 (1,516-5,262) |

Significant at 95%

Of the 808 surgery and control patients, 713 surgery patients and 725 control patients remained at 6 months; 283 surgery patients and 307 controls remained at 36 months. The attrition rate was not statistically different between surgery and control patients.

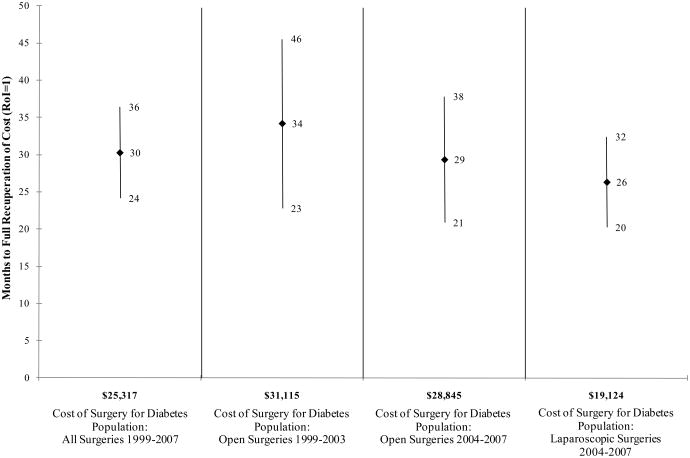

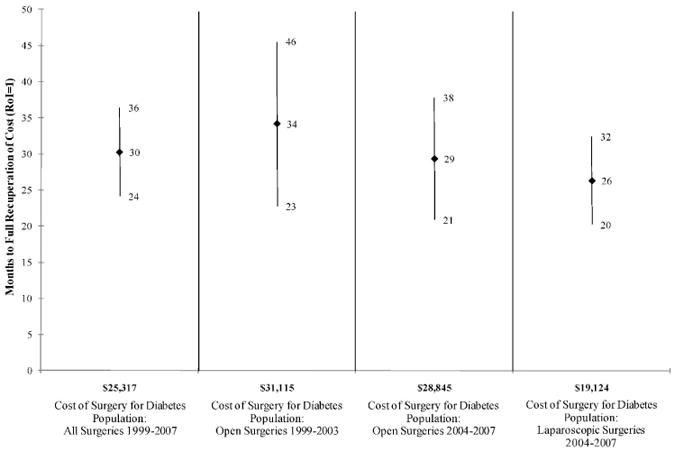

RoI results are presented in Table 2. For surgery patients, the initial investment averaged approximately $25,000 for all surgeries 1999-2007, $31,000 for open surgeries 1999-2003, $29,000 for open surgeries 2004-2007, and $19,000 for laparoscopic surgeries 2004-2007. Cost savings associated with surgery started accruing at month 3. Total surgery costs were fully recovered on average after 30 months in 1999-2007 for all types of surgeries; after 29 months for open surgeries in 2004-2007; and after 26 months for laparoscopic surgeries in 2004-2007.

Table 2. RoI to Bariatric Surgery for Diabetes Patients, Multivariate Analysisa.

| All Surgeries 1999-2007 (N=808) | Open Surgeries 1999-2003 (N=246) | Open Surgeries 2004-2007 (N=204) | Laparoscopic 2004-2007 (N=358) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: Direct Monthly Costs ($) | ||||

| Months Six to Two Prior to Surgery | −199* | −199 | 49 | −221 |

| Month Prior to Surgery | 1,038* | 1,000* | 759* | 1,157* |

| Time of Surgery | 21,247* | 25,623* | 23,148* | 17,092* |

| Month One and Two Following Surgery | 1,516* | 2,246* | 2,469* | 438* |

| Months Three to Six Following Surgery | −500* | −416 | −615* | −464* |

| Months Seven to Twelve Following Surgery | −615* | −597* | −776* | −496* |

| Months Thirteen to Eighteen Following Surgery | −641* | −806* | −643* | −470 |

| Months Nineteen to Twenty-Four Following Surgery | −1,231* | −1,286* | −1,434* | −1,013* |

| Months Twenty-Five and Longer | −1,019* | −1,095* | −1,267* | −1,257* |

| Surgery Cost ($) | 25,317 | 31,115 | 28,845 | 19,124 |

| Months to Full Recuperation of Cost (Mean [95% CI]) | 30 (24,26) | 34 (23,46) | 29 (21,38) | 26 (20,32) |

Significant at 95%

The multivariate model controls for age, gender, and the following comorbidities: breast cancer, congestive heart failure, lymphedema, major depression, osteoarthritis, polycystic ovary syndrome, pseudo tumor cerebri, and venous stasis/leg ulcers.

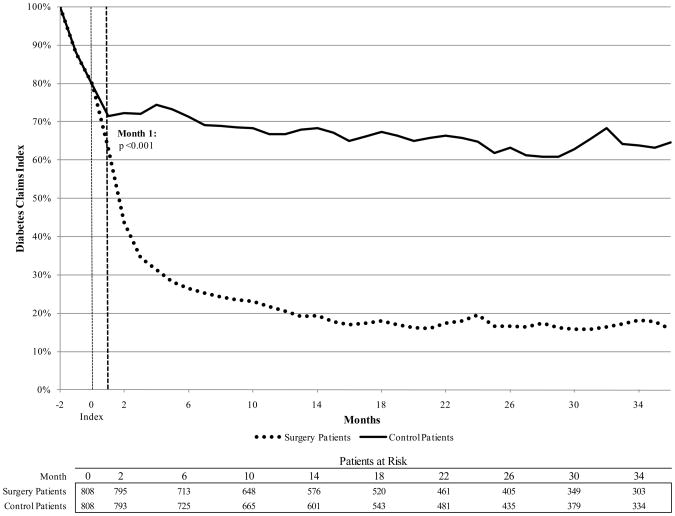

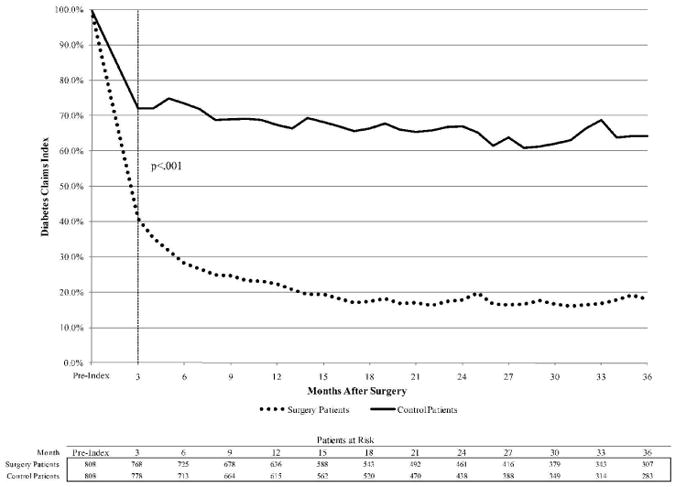

Clinical benefits are the underlying driver of the RoI results. For diagnostic claims of diabetes, by the first three-month period after surgery, 40.7% of surgery patients had a diabetes related claim compared to 72.1% of control patients (p<.001). The post-index decline in diabetes diagnostic claims for the control group likely reflects underdiagnosis as opposed to a true decline. By month 6, only 28.2% of surgery patients reported a claim of diabetes versus 73.5% of control patients (p<.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

RoI to bariatric surgery for U.S. diabetes population, multivariate analysis (mean and 95 percent confidence interval).

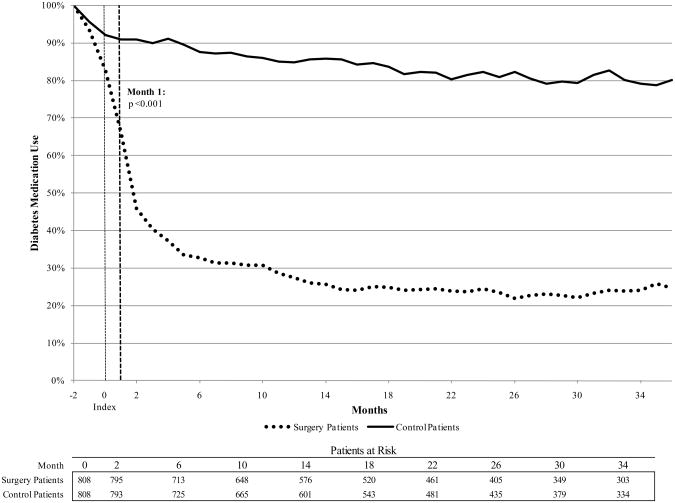

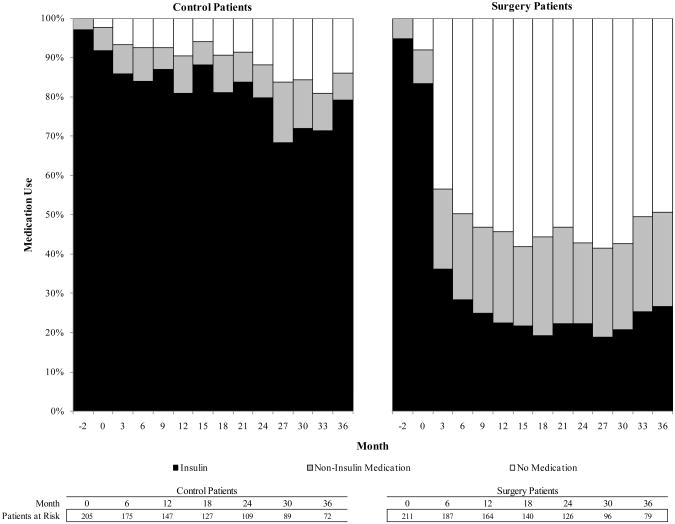

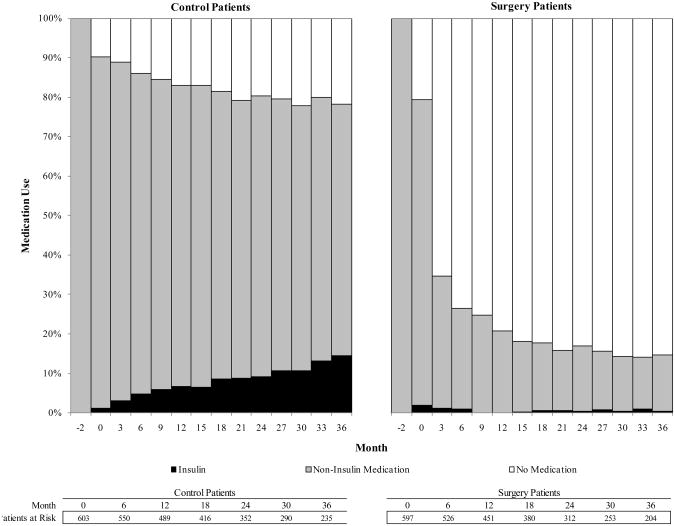

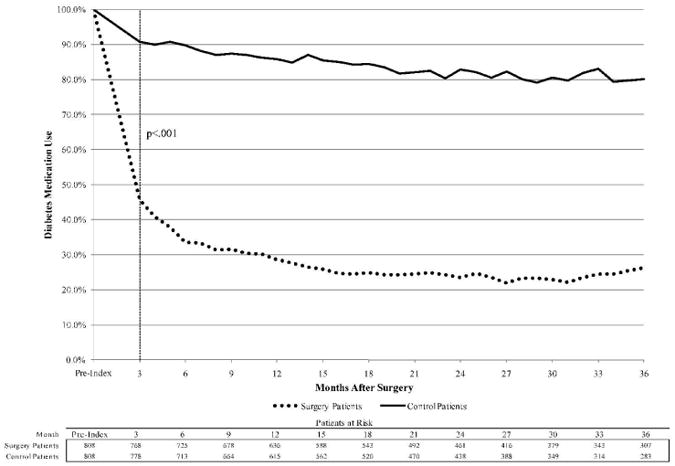

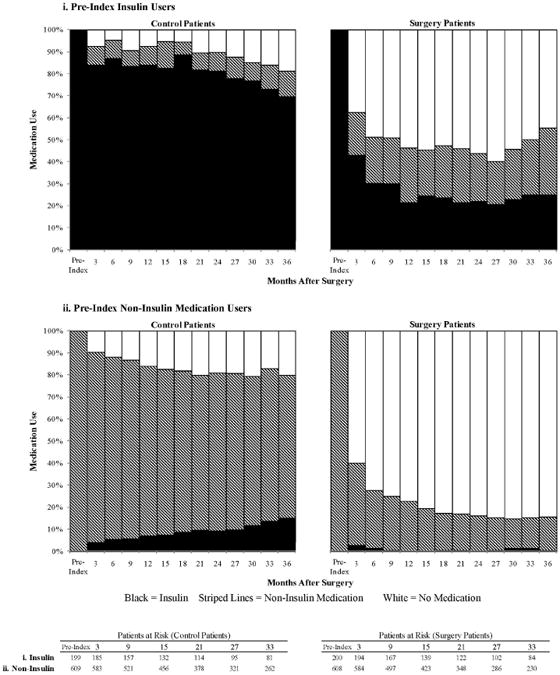

The drug utilization analysis is presented in Figure 2. By the first three-month period post-index, 45.6% of surgery patients had filled a prescription for diabetes medication in the previous 3 months, compared to 90.8% of control patients. At month 6, the percentages were 33.5% and 89.7%, respectively (p<.001). Among patients who had insulin claims prior to index date, insulin claims dropped to 42.8% for surgery patients and remained at 92.4% for control patients at month 3 after index (p<.001). Among surgery patients who had claims for non-insulin diabetes medications prior to surgery, 37.3% had claims for non-insulin medications at month 3, compared with 86.3% of control patients (p<.001); 84.5% of surgery patients who had claims for non-insulin medication at index had no claims for any diabetes medications by month 36.

Figure 2.

Trend of diagnostic claims for diabetes, presented as proportion of patients with diabetes diagnosis and prescription fill during previous 3 months.

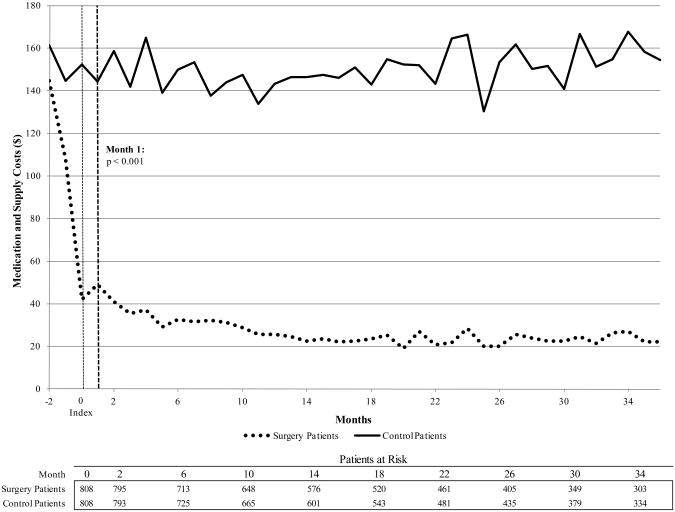

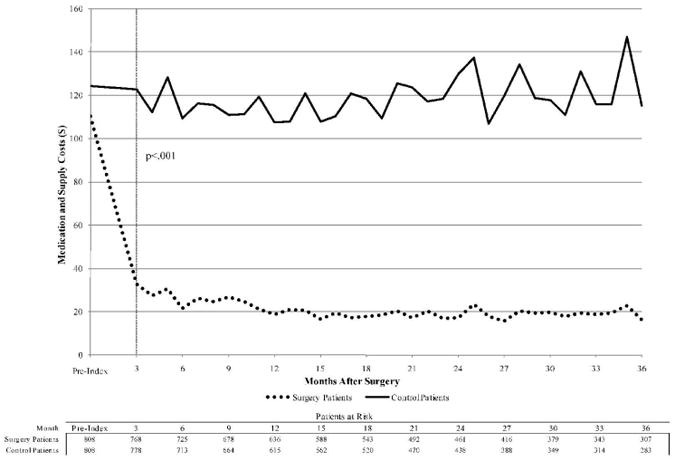

Total diabetes medication costs decreased significantly among surgery patients relative to control patients. By the first three-month period after index, the average total cost of diabetes medications and supplies for surgery patients was $33, compared to $123 for control patients (p<.001). This diabetes drug cost savings trend is sustained for the duration of the study period.

Discussion

Bariatric surgery is the most effective weight loss therapy for obese (BMI ≥35 kg/m2) patients. Current financial concerns surrounding health care has led to an increased interest in evaluating the economic effects of medical and surgical therapies. The results of this study demonstrate that the clinical benefits of bariatric surgery in diabetes patients with BMI ≥35 kg/m2 translate into considerable economic benefits. On average, cost savings began to accrue to third-party payers at 3 months and surgery costs were recovered at 30 months (for open and laparoscopic surgeries, 1999-2007. These data suggest that surgical therapy is clinically more effective and ultimately less expensive than standard therapy for diabetes patients with BMI ≥35 kg/m2.

Our results are consistent with those of Cremieux et al. (12), who employed the same methodology to examine the impact of bariatric procedures on all patients with BMI ≥35 kg/m2, not just those with diabetes. They found costs of laparoscopic procedures were recovered at 25 months. In contrast, a study by Finkelstein et al. (14) found that full cost recovery after surgery took 5 to 10 years. These differences might be due to the reliance on survey data (2000-2001 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey) and simulation methods (Finkelstein et al.) rather than actual claims records (Cremieux et al.) (12).

Our findings support the existing data on the economic impact of bariatric surgery on drug costs. Snow et al.15 reported that average annualized prescription drug costs after laparoscopic gastric bypass surgery were lower, relative to pre-surgery costs, by 68% after 6 months and by 72% after two years. Gould et al. (16) showed monthly cost savings of $120 for medications associated with diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, GERD and depression 6 months post surgery. Monk et al. (17) reported an average monthly medication expenditure reduction of 57% at 6 months after gastric bypass procedures. A 72% monthly medication cost savings was also reported by Nguyen et al. (18), with 69% savings for diabetes medications. Data from the Swedish Obese Subjects Study showed a decrease in diabetes mellitus medication costs after bariatric surgery relative to a matched obese group who did not have surgery (19). Our study shows that average monthly prescription drug costs for surgery patients were 64% lower than for control patients at 6 months after index, 69% lower at one year, and 72% lower at two years. A similar trend was observed for monthly diabetes medication costs.

Our results reinforce and extend previous reports of the clinical benefits of bariatric surgery in diabetes treatment. Prior studies have shown bariatric surgery to be an effective therapy for diabetes in obese patients (9,10,20,21,22). The results from a meta-analysis (23) found that resolution of diabetes after bariatric surgery was achieved in 73% to 88% of patients. This is consistent with our analysis showing that by month 6, 72% of surgery patients no longer had diabetes diagnosis claims. In addition, bariatric surgery reduces the future risk of developing diabetes. The Swedish Obese Subjects Study (23) found that the 10-year incidence of diabetes in bariatric surgery patients was one third that of patients treated with conventional diet therapy. Several recent studies have reported reductions in medication use soon after bariatric surgery (20,24,25), with a rapid decrease in medication use for diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia at three months and a decrease in the mean number of prescription medications per patient from 2.4 before surgery to 0.2 at 12 months after surgery.

The present study has some limitations. First, the claims database did not have data on glycosylated hemoglobin levels, blood pressure measurements or lipid profiles. We used diagnostic codes and prescription fills to identify diabetes patients, which may not reliably estimate true prevalence. However, sensitivity analyses using alternative definitions of diabetes based on the claims information yielded similar results and are available upon request.

Second, BMI, a measure of surgery eligibility and clinical outcome, was not available in the database. However, control patients were matched to surgery patients along multiple demographic factors and 16 comorbidities likely correlated with BMI. More importantly, both surgery and control patients were diagnosed with a BMI of at least 35.

Third, the reliability of the cost savings estimates depends in part on the accuracy of the matching process. While an exact match results in a more balanced sample of patients and controls than a propensity score approach, unobserved characteristics unrelated to index costs, age, gender and selected comorbidities may influence the decision for surgery and cannot be controlled for with the current methodology.

Fourth, there could be differences in lifestyle behaviors, self-management skills, and other diabetes medical treatments between surgery and control patients. Also, some medication use may be misrepresented in the claims database because patients obtain medications from alternative sources (e.g., dual insurance coverage or samples) or may temporarily stop a medication because of a physician recommendation or side effects. However, given the size of the study and its design, it is unlikely that these factors bias the results significantly.

This study demonstrates that bariatric surgery is cost-effective for diabetes patients with BMI ≥35 kg/m2. Additional studies are needed to determine the optimal eligibility criteria for bariatric surgery in diabetes patients based on both clinical and economic cost benefit relationships.

Figure 3.

Trend of diabetes medication claims, presented as proportion of patients with prescription fill during previous 3 months.

Figure 4.

Trend of diabetes medication use for i) pre-index insulin users and ii) pre-index non-insulin medication users.

Figure 5.

Adjusted diabetes medication and supply costs.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: Some of the authors (PYC, AG, SE, TJM) received funding from Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc. The funding source had no role in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, writing the paper, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Appendix.

Appendix Figure 1. RoI to Bariatric Surgery for U.S. Diabetes Population, Multivariate Analysis.

(Mean and 95 Percent Confidence Interval)

Appendix Figure 2. Diagnostic Claims for Diabetes.

(Diabetes Diagnosis and Prescription Fill During Previous 3 Months)

Appendix Figure 3. Trend of Diabetes Medication Claims.

(Prescription Fill During Previous 3 Months)

Appendix Figure 4. Trend of Diabetes Medication Use.

Pre-Index Insulin Users

Appendix Figure 5. Trend of Diabetes Medication Use.

Pre-Index Non-Insulin Medication Users

Appendix Figure 6. Adjusted Diabetes Medication and Supply Costs.

References

- 1.National diabetes fact sheet: United States, 2007. CDC Diabetes. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell RK, Martin TM. The chronic burden of diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:S248–S254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ford ES, Williamson DF, Liu S. Weight changes and diabetes incidence: findings from a national cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiology. 1997;146:214–222. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colditz GA, Willett WC, Rotnitzky A, Manson JE. Weight gain as a risk factor for clinical diabetes mellitus in women. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:481–486. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-122-7-199504010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults. [Accessed June 12,2007. Accessed August 21, 2008];JAMA. 2010 Jan 13; doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. published online. http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health/nutrit/pubs/statobes.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Cawley J, Rizzo J, Gunnarsson C, Haas K. The health care cost effects of diabetes among obese and morbidly obese adults in the United States; Poster presented at International Society of Pharmacoeconomic Outcomes Research (ISPOR) 13th Annual International meeting; Toronto, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wing RR, Koeske R, Epstein LH, Nowalk MP, Gooding W, Becker D. Long-term effects of modest weight loss in type II diabetic patients. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1749–1753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG, et al. Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 1995;222(3):339–352. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199509000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dixon JB, O'Brien PE, Playfair J, et al. Adjustable gastric banding and conventional therapy for type 2 diabetes. JAMA. 2008;299(3):316–323. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schauer PR, Ikramuddin S, Gourash W, Ramanathan R, Luketich J. Outcomes of laparoscopic roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2000;232(4):515–529. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200010000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pladevall M, Williams LK, Potts LA, Divine G, Xi H, Lafata JE. Clinical Outcomes and Adherence to Medications Measured by Claims Data in Patients With Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(12):2800–2805. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crémieux PY, Buchwald H, Shikora SA, Ghosh A, Yang HE, Buessing M. A study on the economic impact of bariatric surgery. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(9):589–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Society for Bariatric Surgery Web site. [Accessed August 15, 2007];Guidelines for granting privileges in bariatric surgery. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2005.10.012. http://www.asbs.org/html/guidelines.html. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Finkelstein EA, Brown DS. A cost-benefit simulation model of coverage for bariatric surgery among full-time employees. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:641–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snow LL, Weinstein LS, Hannon JK, et al. The effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on prescription drug costs. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1031–5. doi: 10.1381/0960892041975677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gould JC, Garren MJ, Starling JR. Laparoscopic gastric bypass results in decreased prescription medication costs within 6 months. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:983–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monk JS, Jr, Dia Nagib N, Stehr W. Pharmaceutical savings after gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2004;14:13–5. doi: 10.1381/096089204772787220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ninh T, Nguyen J, Varela E, Sabio A, Tran CL, Stamos M, Wilson SE. Reduction in Prescription Costs after Laparoscopic Gastric Bypass. The American Surgeon. 2006;72:853–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Narbro K, Agren G, Jonsson E, Näslund I, Sjöström L, Peltonen M. Pharmaceutical costs in obese individuals: comparison with a randomly selected population sample and long-term changes after conventional and surgical treatment: the SOS intervention study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2061–2069. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.18.2061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sjöström L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after baraitric surgery. NEJM. 2004;351(26):2683–2893. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogula T, Brethauer S, Chand B, Schauer P. Bariatric surgery may cure type 2 diabetes in some patients. 2009 Nov 23; Sourced from http://my.clevelandclinic.org/bariatric_surgery/Documents/Microsoft%20Word%20%20Diabetes_pts_info2_response%20to%2060%20minutes.pdf.

- 22.Czupryniak L, Strzelczyk J, Cypryk K, et al. Gastric bypass surgery in severely obese type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(10):2561–2562. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, Banel D, Jensen MD, Pories WJ. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2009;122(3):248–256. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Segal JB, Clark JM, Shore AD, et al. Prompt Reduction in Use of Medications for Comorbid Conditions After Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2009;19(12):1646–56. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9960-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodom PHDM, Waller JL, Martindale RG, Fick DM. Medication use after bariatric surgery in a managed care cohort. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(5):601–7. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]