Abstract

Activation of innate immune systems including Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling is a key in chronic liver disease. Recent studies suggest that gut microflora-derived bacterial products (i.e. LPS, bacterial DNA) and endogenous substances (i.e. HMGB1, free fatty acids) released from damaged cells activate hepatic TLRs that contribute to the development of alcoholic (ASH) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and liver fibrosis. The crucial role of TLR4, a receptor for LPS, has been implicated in the development of ASH, NASH, liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. However, the role of other TLRs, such as TLR2 and TLR9 in chronic liver disease remains less clear. In this review, we will discuss the role of TLR2, 4 and 9 in Kupffer cells and hepatic stellate cells in the development of ASH, NASH and hepatocarcinogenesis.

Keywords: TLR4, MyD88, LPS, Liver fibrosis, intestinal microflora

Introduction

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a family of pattern-recognition receptors that play a critical role in the activation of innate immune system by recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs).1, 2 Endogenous components derived from dying host cells, termed damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), can also activate TLRs.3, 4 To date, more than 10 members of the TLR family have been identified in mammals. TLRs are type I transmembrane proteins characterized by an extracellular leucine-rich domain and a cytoplasmic tail that is responsible for ligand recognition.1, 2 After binding to corresponding ligands, TLRs transduce signals via myeloid differentiation factor (MyD) 88, a common signal adaptor molecule shared by IL-1 receptor and all members of TLRs except for TLR3.1, 2 This cascade leads to the activation of NF-κB and results in the production of various proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and IL-6. The MyD88-dependent pathway activates p38 and c-Jun N terminal kinase (JNK) as well. In contrast, TLR3 and TLR4 utilize MyD88-independent, TIR domain-containing adaptor-inducing interferon-β (TRIF)-dependent pathway. Subsequently, TRIF associates with TRAF3 and TRAF6 to activate TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and IKKi, which results in the activation of transcription factor IRF3 and induction of IFN-β.1, 2 Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that TLRs play important roles in the pathophysiology of a variety of liver diseases,5 which may attribute to wide expression of TLRs on all types of liver cells, including hepatocytes,5, 6 Kupffer cells,5, 7 sinusoidal endothelial cells,8 hepatic stellate cells (HSCs),9–11 biliary epithelial cells,5 as well as immune cells such as liver dendritic cells.8 In this review, we summarize the recent findings regarding the role of TLRs in alcoholic liver disease (ALD), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

TLR4 and ALD

It has been acknowledged for many years that chronic alcohol abuse causes hepatic steatosis, alcoholic hepatitis, and ultimately cirrhosis. The pathogenesis of ALD involves complex interaction between the direct effects of alcohol and its metabolite, acetaldehyde, in various cell types in the liver.12, 13 Activation of Kupffer cells via TLR4 signaling is crucial in the pathogenesis of alcohol-induced liver injury. Since the disruption of intestinal barrier by ethanol generally increases permeability for macromolecular substances,14 LPS levels in systemic and portal blood are significantly increased in patients and animals with chronic alcohol consumption.15–17 Mice deficient in TLR4, CD14 and LBP are resistant to alcohol-induced liver injury.16, 18, 19 Moreover, gut sterilization with antibiotics decreased plasma LPS levels, liver steatosis, inflammation, and injury in mice on chronic ethanol abuse.20 Thus, it is conceivable that translocated LPS from the gut microflora activates hepatic TLR4 signaling in alcoholic liver disease. Although LPS alone fails to mimic the pathology of alcoholic steatohepatitis, ethanol administration increases the sensitivity to LPS-induced hepatocyte injury and cytokine production in the animal model.21, 22 Previous studies emphasized the pathophysiological importance of TLR4 on Kupffer cells in alcoholic liver disease, however, lacked to demonstrate the role of TLR4 on HSCs.16, 20 A recently published study investigated the relative contribution of TLR4 expressed on Kupffer cells and HSCs in ALD.23 In addition to the previously established concept, it demonstrated that TLR4 signaling is important in both bone marrow (BM)-derived cells including Kupffer cells, and endogenous liver cells including HSCs for alcohol-induced hepatocyte injury, steatosis, inflammation and fibrogenesis.23 Moreover, activation of TLR4 signaling in HSCs is more important than TLR4 in Kupffer cells for HSC activation. In HSCs, activated TLR4 signaling downregulates TGF-β pseudoreceptor Bambi, resulting in enhancement of TGF-β signaling.11 Bambi downregulation is dependent on MyD88, but not TRIF.11 Interestingly, the TLR4-TRIF-IRF3 dependent pathway is more important than the TLR4-MyD88 dependent pathway to develop alcoholic steatohepatitis, and the responsible cell types for the TLR4-TRIF-IRF3 pathway are BM-derived cells including Kupffer cells.12, 24

In addition to LPS, other bacterial products can be translocated into the portal vein in individuals with chronic alcohol consumption. In particular, bacterial DNA was found in serum and ascites of patients with advanced liver cirrhosis that lead to increases of cytokine production in peritoneal macrophages.25, 26 Bacterial DNA, which is recognized by TLR9, sensitizes the liver to injury induced by LPS via upregulation of TLR4, MD-2, and induction Th1-type immune response in the liver.27 Therefore, it is highly anticipated that TLR9 signaling will influence pathogenesis of alcohol liver disease. However, it has yet to be fully elucidated.

Expression of TLR1, 2, 6, 7, and 8 was elevated in wild-type mice that received the Lieber-DeCarli chronic alcohol-feeding model. The treatment with alcohol resulted in sensitization to liver inflammation and damage by TLR1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8, and 9 ligands due to increased expression of TNF-α.28 However, some investigations found deficiency in TLR2 had no protective effect on alcohol-induced liver injury in a chronic ethanol feeding mouse model.24

Taken together, it is clear that alcohol consumption leads to the activation of innate immunity via TLRs signaling. Recent studies demonstrated that TLR4 signaling contributes to the dissection of molecular mechanism in ALD, indicating the indispensible role of both Kupffer cells and HSCs in mediating the effect of gut-derived endotoxin in ALD and suggesting the role of other TLRs in modulation of alcohol-induced liver injury.

Toll-Like Receptors in NASH

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome. NASH is characterized by steatosis, inflammation, and progressive fibrosis that ultimately lead to the end-stage of liver disease.29, 30 Recent evidence suggests that overgrowth of intestinal bacteria and increased intestinal permeability are associated with the development of NASH.31, 32 In chronic liver disease, including NASH, intestinal permeability is increased due to bacterial overgrowth or altered composition of bacterial microflora.33 Systemic inflammation related to NASH also injures epithelial tight junctions,31 resulting in deregulation of intestinal barrier functions. Indeed, plasma levels of LPS were elevated in patients with chronic liver diseases, including NASH.34 These findings suggest that hepatic immune cells might be exposed to high levels of TLR ligands derived from gut bacterial products, which might trigger liver injury in NASH. In fact, several reports demonstrated the importance of TLR4 and intestine-derived LPS in the animal model of NASH.35, 36 Interestingly, pathological effect of TLR4 in Kupffer cells is achieved by inducing ROS-dependent activation of X-box binding protein-1 (XBP-1).37 Moreover, other bacterial products such as bacterial DNA, a ligand for TLR9, was detected in the blood of the murine NASH model developed by 22 weeks of choline-deficient amino acid-defined (CDAA) diet feeding.38 This evidence suggests that activation of TLR9 signaling plays an important role in the development of NASH. In CDAA diet-induced NASH, translocated bacterial DNA binds to TLR9 on Kupffer cells to produce IL-1β, which in turn stimulates hepatocytes for lipid accumulation and cell death. Concurrently, IL-1β activates HSCs to induce liver fibrosis.38 Besides TLR4 and TLR9, TLR2 also plays crucial role in the progression of NASH. In CDAA-diet induced NASH, TLR2 mediates liver inflammation and fibrosis, and the indispensable cell type expressing functional TLR2 is Kupffer cells. However, induction of hepatic steatosis is independent of TLR2 signaling. 39

Several plausible theories have been proposed to explain the ability of FFAs to activate TLR signals. Nonpathogenic substances may act as TLR ligands, as free fatty acids (FFAs) and denatured host DNA activate TLR2, TLR4 and TLR9.10, 40–42 For instance, palmitic acid and oleic acid act through TLR4 on macrophages and 293 cells.41 Palmitic acid and stearic acid, potential TLR4 ligands, are abundant in dietary fat, and high levels of circulating FFAs have been observed in patients with NAFLD.43 In addition, it is intriguing that the lipid component of LPS is sufficient to trigger TLR4 signaling. In particular, a medium-chain fatty acid component of LPS, lauric acid, has been shown to initiate TLR4 signaling in a macrophage cell line.44, 45 These data suggest a strong relevance between TLR4 and lipid components. However, several reports have shown that FFAs do not directly stimulate TLR4 signaling.46, 47 Since hepatocytes undergo apoptosis and necrosis in NASH, liver cells may constantly be exposed to denatured host DNA. However, it is not clear whether host DNA is a functional ligand for TLR9. Indeed, the unmethylated CpG-motif is uncommon in mammalian DNAs.48 Although some FFAs and denatured host DNA are attractive candidates for TLR ligands, further investigations are needed to determine whether these substances are capable of activating TLRs in NAFLD.

Recent studies have focused on TLR signaling in Kupffer cells that mediates the progression of simple steatosis to NASH. Other resident liver cells and BM-derived immune cells also produce various mediators modulating the severity of NAFLD in response to TLR ligands. Thus, understanding of cell type-specific TLR signaling will provide new insight into the therapeutic management of NAFLD.

Toll-Like Receptors and Carcinogenesis

Approximately 80% of HCC are preceded by chronic liver inflammation, fibrosis and cirrhosis.49 Under the pathologic conditions, the liver may be exposed to various TLR ligands via the portal vein, leading to an uncontrolled activation of innate immunity that may result in inflammatory liver diseases.5 Many factors are capable of activating TLRs in the liver. Among them, fibrosis, hepatitis B and C infection, alcoholic liver disease, and NASH are important etiologies for HCC. Therefore, it seems clear that TLRs play a role in the inflammation-associated liver cancer development. The chemical carcinogen, diethylnitrosamine (DEN), induces hepatocyte death, compensatory proliferation and eventually HCC development in mice, closely resembling human HCC with poor prognosis.50, 51 Mice deficient in TLR4 and MyD88, but not TLR2, have marked decreases in the incidence, size, and number of chemical-induced liver cancer, indicating a strong contribution of TLR signaling to hepatocarcinogenesis.5, 52 Recently, two reports demonstrated that gut microbiota and TLR4 play a role in HCC promotion, but not in HCC initiation, mediating increased proliferation, production of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6), expression of the hepatomitogen epiregulin, and prevention of apoptosis. Interestingly, gut sterilization, germfree status or TLR4 inactivation significantly reduced the development of HCC.53, 54 Clinical and epidemiological evidence implicates long-term alcohol consumption in accelerating HCV-mediated tumorigenesis. HCV NS5A transgenic mice with long-term alcohol feeding develop typical tumors associated with NS5A mediated TLR4 overexpression in hepatocytes.55 Recently, we reported that hepatocyte-specific TAK1 deleted (TAK1ΔHEP) mice generated by intercrossing TAK1 floxed mice with Alb-Cre mice showed spontaneous HCC development.56 In TAK1ΔHEP mice, additional deletion of MyD88, TLR4 or TLR9 signaling provides a resistance for HCC development. (Seki, unpublished data)

To understand liver tumorigenesis, it is very important to analyze which cell types are involved in the process. Kupffer cells may be the major cells expressing TLRs in the liver. Kupffer cells are liver tissue macrophages and express most of the major TLRs. In contrast, hepatocytes, the liver parenchymal cells, only show weak TLR2 and TLR4 expression and less response against their ligands.57 TLR2 expression in hepatocytes is upregulated by LPS, TNF, and others, which suggest that hepatocytes become more sensitive in the inflammatory condition.58 It is assumed that dying hepatocytes following DEN may activate myeloid cells such as Kupffer cells via TLRs and induce proinflammatory cytokines and hepatomitogens, such as IL-6, which enhance the development of HCC.54, 59 However, Schwabe and colleagues argued that TLR4 on resident liver cells, but not BM-derived cells is required for promotion of HCC.53

In conclusion, there is clear evidence that TLRs and MyD88 signaling is associated with hepatic inflammation and hepatomitogen expression, which appear to be essential for hepatocarcinogenesis. These observations suggest that better understanding of TLR signaling pathways in the liver will help to clarify the mechanisms of liver tumorigenesis and provide new therapeutic targets for HCC.

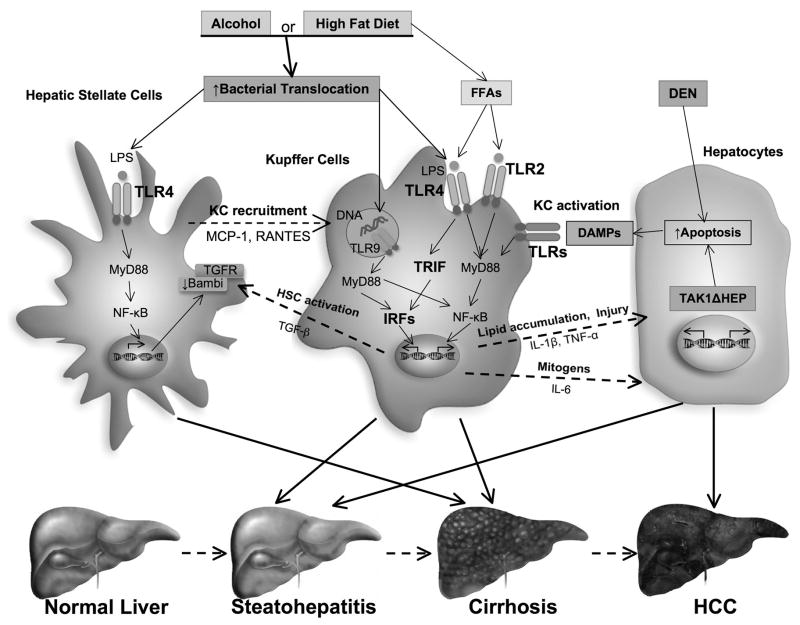

Figure 1. Role of TLRs in ALD, NAFLD and HCC.

Following alcohol consumption or excessive high fat diet intake, bacterial translocation occurs due to the overgrowth of intestinal bacteria or disruption of intestinal barrier functions. Translocated intestine–derived PAMPs (LPS and DNA) activate TLR signaling cascades in multiple hepatic cell types that regulate the inflammatory response. TLR2, TLR4 and TLR9 activation on Kupffer cells (KCs) induces production of various cytokines such as TGFβ, IL-1β and TNFα, that subsequently induce hepatic stellate cell (HSC) activation and hepatocyte lipid accumulation and apoptosis. TLR4 activation on HSCs has also been shown to promote recruitment of KCs and directly augments fibrogenic response through downregulation of Bambi. Downstream signaling events include the MyD88-dependent NF-κB activation and TRIF-dependent IRF activation. Additionally, dead hepatocytes cause activation of KCs via TLRs and induces production of inflammatory cytokines and mitogen such as IL-6, which promote the HCC development. Consequently, hepatic TLRs play a pivotal role in the four sequential hallmarks of liver disease: steatosis, steatohepatitis, fibrosis and HCC.

Acknowledgments

Financial support:

This study is supported by NIH grant R01AA02172 (ES), R01DK085252 (ES), P42ES 010337 (Project5, ES).

Nonstandard abbreviations used

- ALD

alcoholic liver disease

- ASH

alcoholic steatohepatitis

- BM

bone marrow

- CDAA

choline deficient amino acid defined

- DAMP

damage-associated molecular pattern

- DEN

diethylnitrosamine

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HSC

hepatic stellate cells

- JNK

c-Jun N terminal kinase

- MyD

myeloid differentiation factor

- NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- PAMP

pathogen-associated molecular pattern

- TAK1ΔHEP

hepatocyte-specific TAK1 deleted

- TBK1

TANK-binding kinase 1

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

- XBP-1

X-box binding protein-1

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: There is no conflict of interest to disclose for all authors.

References

- 1.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yamamoto M, Takeda K. Current views of toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2010;2010:240365. doi: 10.1155/2010/240365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen CJ, Kono H, Golenbock D, Reed G, Akira S, Rock KL. Identification of a key pathway required for the sterile inflammatory response triggered by dying cells. Nature Medicine. 2007;13:851–6. doi: 10.1038/nm1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, Sumi Y, Sursal T, Junger W, et al. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010;464:104–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seki E, Brenner DA. Toll-like receptors and adaptor molecules in liver disease: update. Hepatology. 2008;48:322–35. doi: 10.1002/hep.22306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isogawa M, Robek MD, Furuichi Y, Chisari FV. Toll-like receptor signaling inhibits hepatitis B virus replication in vivo. Journal of Virology. 2005;79:7269–72. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.11.7269-7272.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seki E, Tsutsui H, Nakano H, Tsuji N, Hoshino K, Adachi O, et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-18 secretion from murine Kupffer cells independently of myeloid differentiation factor 88 that is critically involved in induction of production of IL-12 and IL-1beta. Journal of Immunology. 2001;166:2651–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.4.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu J, Meng Z, Jiang M, Zhang E, Trippler M, Broering R, et al. Toll-like receptor-induced innate immune responses in non-parenchymal liver cells are cell type-specific. Immunology. 2010;129:363–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03179.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paik YH, Schwabe RF, Bataller R, Russo MP, Jobin C, Brenner DA. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates inflammatory signaling by bacterial lipopolysaccharide in human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2003;37:1043–55. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watanabe A, Hashmi A, Gomes DA, Town T, Badou A, Flavell RA, et al. Apoptotic hepatocyte DNA inhibits hepatic stellate cell chemotaxis via toll-like receptor 9. Hepatology. 2007;46:1509–18. doi: 10.1002/hep.21867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–32. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petrasek J, Mandrekar P, Szabo G. Toll-like receptors in the pathogenesis of alcoholic liver disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2010 doi: 10.1155/2010/710381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szabo G, Bala S. Alcoholic liver disease and the gut-liver axis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1321–9. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i11.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rao R. Endotoxemia and gut barrier dysfunction in alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;50:638–44. doi: 10.1002/hep.23009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukui H, Brauner B, Bode JC, Bode C. Plasma endotoxin concentrations in patients with alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver disease: reevaluation with an improved chromogenic assay. Journal of Hepatology. 1991;12:162–9. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90933-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uesugi T, Froh M, Arteel GE, Bradford BU, Thurman RG. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in the mechanism of early alcohol-induced liver injury in mice. Hepatology. 2001;34:101–8. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yan AW, Fouts DE, Brandl J, Starkel P, Torralba M, Schott E, et al. Enteric dysbiosis associated with a mouse model of alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53:96–105. doi: 10.1002/hep.24018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Uesugi T, Froh M, Arteel GE, Bradford BU, Wheeler MD, Gabele E, et al. Role of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein in early alcohol-induced liver injury in mice. Journal of Immunology. 2002;168:2963–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yin M, Bradford BU, Wheeler MD, Uesugi T, Froh M, Goyert SM, et al. Reduced early alcohol-induced liver injury in CD14-deficient mice. Journal of Immunology. 2001;166:4737–42. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.7.4737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adachi Y, Moore LE, Bradford BU, Gao W, Thurman RG. Antibiotics prevent liver injury in rats following long-term exposure to ethanol. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:218–24. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pennington HL, Hall PM, Wilce PA, Worrall S. Ethanol feeding enhances inflammatory cytokine expression in lipopolysaccharide-induced hepatitis. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 1997;12:305–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1997.tb00426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Montfort C, Beier JI, Guo L, Kaiser JP, Arteel GE. Contribution of the sympathetic hormone epinephrine to the sensitizing effect of ethanol on LPS-induced liver damage in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G1227–34. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00050.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inokuchi S, Tsukamoto H, Park E, Liu ZX, Brenner DA, Seki E. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates alcohol-induced steatohepatitis through bone marrow-derived and endogenous liver cells in mice. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35:1509–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hritz I, Mandrekar P, Velayudham A, Catalano D, Dolganiuc A, Kodys K, et al. The critical role of toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 in alcoholic liver disease is independent of the common TLR adapter MyD88. Hepatology. 2008;48:1224–31. doi: 10.1002/hep.22470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frances R, Benlloch S, Zapater P, Gonzalez JM, Lozano B, Munoz C, et al. A sequential study of serum bacterial DNA in patients with advanced cirrhosis and ascites. Hepatology. 2004;39:484–91. doi: 10.1002/hep.20055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frances R, Munoz C, Zapater P, Uceda F, Gascon I, Pascual S, et al. Bacterial DNA activates cell mediated immune response and nitric oxide overproduction in peritoneal macrophages from patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Gut. 2004;53:860–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.027425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romics L, Jr, Dolganiuc A, Kodys K, Drechsler Y, Oak S, Velayudham A, et al. Selective priming to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), not TLR2, ligands by P. acnes involves up-regulation of MD-2 in mice. Hepatology. 2004;40:555–64. doi: 10.1002/hep.20350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gustot T, Lemmers A, Moreno C, Nagy N, Quertinmont E, Nicaise C, et al. Differential liver sensitization to toll-like receptor pathways in mice with alcoholic fatty liver. Hepatology. 2006;43:989–1000. doi: 10.1002/hep.21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powell EE, Cooksley WG, Hanson R, Searle J, Halliday JW, Powell LW. The natural history of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: a follow-up study of forty-two patients for up to 21 years. Hepatology. 1990;11:74–80. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840110114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miura K, Seki E, Ohnishi H, Brenner DA. Role of toll-like receptors and their downstream molecules in the development of nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2010;2010:362847. doi: 10.1155/2010/362847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miele L, Valenza V, La Torre G, Montalto M, Cammarota G, Ricci R, et al. Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:1877–87. doi: 10.1002/hep.22848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brun P, Castagliuolo I, Di Leo V, Buda A, Pinzani M, Palu G, et al. Increased intestinal permeability in obese mice: new evidence in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G518–25. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00024.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu WC, Zhao W, Li S. Small intestinal bacteria overgrowth decreases small intestinal motility in the NASH rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:313–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farhadi A, Gundlapalli S, Shaikh M, Frantzides C, Harrell L, Kwasny MM, et al. Susceptibility to gut leakiness: a possible mechanism for endotoxaemia in non- alcoholic steatohepatitis. Liver Int. 2008;28:1026–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01723.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Csak T, Velayudham A, Hritz I, Petrasek J, Levin I, Lippai D, et al. Deficiency in myeloid differentiation factor-2 and toll-like receptor 4 expression attenuates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2011;300:G433–41. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00163.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rivera CA, Adegboyega P, van Rooijen N, Tagalicud A, Allman M, Wallace M. Toll-like receptor-4 signaling and Kupffer cells play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Journal of Hepatology. 2007;47:571–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ye D, Li FY, Lam KS, Li H, Jia W, Wang Y, et al. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates obesity-induced non-alcoholic steatohepatitis through activation of X-box binding protein-1 in mice. Gut. 2012;61:1058–67. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miura K, Kodama Y, Inokuchi S, Schnabl B, Aoyama T, Ohnishi H, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 promotes steatohepatitis by induction of interleukin-1beta in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:323–34 e7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miura K, Yang L, van Rooijen N, Brenner DA, Ohnishi H, Seki E. TLR2 and palmitic acid cooperatively contribute to the development of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis through inflammasome activation. Hepatology. 2012 doi: 10.1002/hep.26081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Senn JJ. Toll-like receptor-2 is essential for the development of palmitate-induced insulin resistance in myotubes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:26865–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513304200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi H, Kokoeva MV, Inouye K, Tzameli I, Yin H, Flier JS. TLR4 links innate immunity and fatty acid-induced insulin resistance. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2006;116:3015–25. doi: 10.1172/JCI28898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zu L, He J, Jiang H, Xu C, Pu S, Xu G. Bacterial endotoxin stimulates adipose lipolysis via toll-like receptor 4 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009;284:5915–26. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807852200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Almeida IT, Cortez-Pinto H, Fidalgo G, Rodrigues D, Camilo ME. Plasma total and free fatty acids composition in human non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Clinical Nutrition. 2002;21:219–23. doi: 10.1054/clnu.2001.0529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee JY, Ye J, Gao Z, Youn HS, Lee WH, Zhao L, et al. Reciprocal modulation of Toll-like receptor-4 signaling pathways involving MyD88 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT by saturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:37041–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee JY, Sohn KH, Rhee SH, Hwang D. Saturated fatty acids, but not unsaturated fatty acids, induce the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 mediated through Toll-like receptor 4. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276:16683–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011695200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schaeffler A, Gross P, Buettner R, Bollheimer C, Buechler C, Neumeier M, et al. Fatty acid-induced induction of Toll-like receptor-4/nuclear factor-kappaB pathway in adipocytes links nutritional signalling with innate immunity. Immunology. 2009;126:233–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2008.02892.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Erridge C, Samani NJ. Saturated fatty acids do not directly stimulate Toll-like receptor signaling. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2009;29:1944–9. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.194050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stacey KJ, Young GR, Clark F, Sester DP, Roberts TL, Naik S, et al. The molecular basis for the lack of immunostimulatory activity of vertebrate DNA. Journal of Immunology. 2003;170:3614–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alderton GK. Inflammation: the gut takes a toll on liver cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:379. doi: 10.1038/nrc3283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Maeda S, Kamata H, Luo JL, Leffert H, Karin M. IKKbeta couples hepatocyte death to cytokine-driven compensatory proliferation that promotes chemical hepatocarcinogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:977–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lee JS, Chu IS, Mikaelyan A, Calvisi DF, Heo J, Reddy JK, et al. Application of comparative functional genomics to identify best-fit mouse models to study human cancer. Nature Genetics. 2004;36:1306–11. doi: 10.1038/ng1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Naugler WE, Sakurai T, Kim S, Maeda S, Kim K, Elsharkawy AM, et al. Gender disparity in liver cancer due to sex differences in MyD88-dependent IL-6 production. Science. 2007;317:121–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1140485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dapito DH, Mencin A, Gwak GY, Pradere JP, Jang MK, Mederacke I, et al. Promotion of hepatocellular carcinoma by the intestinal microbiota and TLR4. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:504–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu LX, Yan HX, Liu Q, Yang W, Wu HP, Dong W, et al. Endotoxin accumulation prevents carcinogen-induced apoptosis and promotes liver tumorigenesis in rodents. Hepatology. 2010;52:1322–33. doi: 10.1002/hep.23845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Machida K, Tsukamoto H, Mkrtchyan H, Duan L, Dynnyk A, Liu HM, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates synergism between alcohol and HCV in hepatic oncogenesis involving stem cell marker Nanog. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:1548–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807390106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Inokuchi S, Aoyama T, Miura K, Osterreicher CH, Kodama Y, Miyai K, et al. Disruption of TAK1 in hepatocytes causes hepatic injury, inflammation, fibrosis, and carcinogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:844–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909781107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu S, Gallo DJ, Green AM, Williams DL, Gong X, Shapiro RA, et al. Role of toll-like receptors in changes in gene expression and NF-kappa B activation in mouse hepatocytes stimulated with lipopolysaccharide. Infection and Immunity. 2002;70:3433–42. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3433-3442.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsumura T, Ito A, Takii T, Hayashi H, Onozaki K. Endotoxin and cytokine regulation of toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 gene expression in murine liver and hepatocytes. Journal of Interferon and Cytokine Research. 2000;20:915–21. doi: 10.1089/10799900050163299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maeda S, Omata M. Inflammation and cancer: role of nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:836–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00763.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]