Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus causes the majority of human skin and soft tissue infections, and is a major infectious cause of mortality. Host defense mechanisms against S. aureus are incompletely understood. Interleukin (IL)-19, -20 and -24 signal through type I and type II IL-20 receptors and are associated with inflammatory skin diseases such as psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. We show here that these cytokines promote cutaneous S. aureus infection in mice by downregulating IL-1β- and IL-17A-dependent pathways. Similar effects of these cytokines were seen in human keratinocytes after S. aureus exposure, and antibody blockade of IL-20 receptor improved outcomes in infected mice. Our findings identify an immunosuppressive role for these cytokines during infection that could be therapeutically targeted to alter susceptibility to infection.

Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequent cause of skin and soft tissue infection in the United States. It is the leading cause of hospital-acquired infection, and invasive S. aureus infections annually account for more American deaths than HIV, viral hepatitis, and influenza combined1. In recent years, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), resistant to routine anti-staphylococcal antibiotics, has become a concern beyond the hospital setting, with distinct ‘community-associated’ strains such as USA300 causing epidemic outbreaks, and reservoirs of these drug-resistant strains tainting meat and poultry samples in the U.S. and other countries2,3.

As a frequent colonizer of human skin and mucosa, S. aureus may be considered a commensal symbiont with pathogenic potential, or pathobiont4, that has developed multiple mechanisms to evade and manipulate the host response5-8. Immune responses required to control this important organism are incompletely understood. Although adaptive immune responses develop during S. aureus infections, T and B cells are not required to clear S. aureus infections in mice and the adaptive immune response that develops during primary infection appears to be largely ineffective at preventing subsequent infection9-13. Recent work has revealed the central and protective role of cytokines such as IL-1β and IL-17A in triggering a neutrophil-dependent innate immune response14-16. Further insights into the immune mechanisms required to control S. aureus may identify vaccination and therapeutic strategies to combat the rise of antibiotic-resistant disease.

IL-19, IL-20, IL-22, IL-24 and IL-26 comprise the IL-20 subfamily of cytokines, a subset of the IL-10 superfamily, which also includes IL-10, IL-28, and IL-2917-19. IL-19, IL-20, and IL-24 all signal through the type I IL-20 receptor (IL-20R), a heterodimeric receptor composed of the IL-20R alpha and beta chains (IL20RA and IL20RB). IL-20 and IL-24 can additionally signal through the type II IL-20R, an IL20RB and IL22 receptor alpha 1 (IL22RA1) heterodimer. Recent work has clarified the structural basis for the specific binding characteristics of these receptors and cytokines20. Both of these IL20RB-contaning receptor complexes are primarily expressed on epithelial cells and activate the transcription factor STAT3. This activation drives a program that restores tissue homeostasis by enhancing remodeling, wound healing, and antimicrobial peptide secretion in a manner similar to the actions of IL-2221. Distinct from IL-22, which is primarily secreted by lymphocytes, IL-19, IL-20, and IL-24 are produced primarily by myeloid and epithelial cells18.

IL-19, IL-20, and IL-24, which we will refer to as IL-20R cytokines, have been implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. High expression of all IL-20R cytokines has been found in psoriatic tissue samples22. In mice and tissue culture systems, overexpression of IL-20 or IL-24 leads to characteristic keratinocyte proliferation, epidermal thickening, and induction of psoriasis-associated chemokines and antimicrobial peptides21,23,24. IL-17A and IL-22, driven by IL-23-mediated STAT3 activation, are also implicated in psoriasis pathogenesis and have been found to induce IL-20 subfamily members21,25,26.

Although the IL-20R cytokines have been associated with psoriasis and other immunopathology, their role in host defense has not been extensively investigated27,28. Given their demonstrated skin-protective actions, we hypothesized that these cytokines would enhance the anti-staphylococcal host response. However, we found that signaling through IL20RB inhibited the cutaneous inflammatory response and reduced production of IL-1β and IL-17A, and thereby promoted S. aureus skin infection. These results identify an anti-inflammatory role for IL20RB signaling that is consistent with its previously described tissue-restorative functions but imparts diminished host defense against infectious agents at epithelial surfaces.

RESULTS

IL-20RB impairs control of cutaneous S. aureus infection

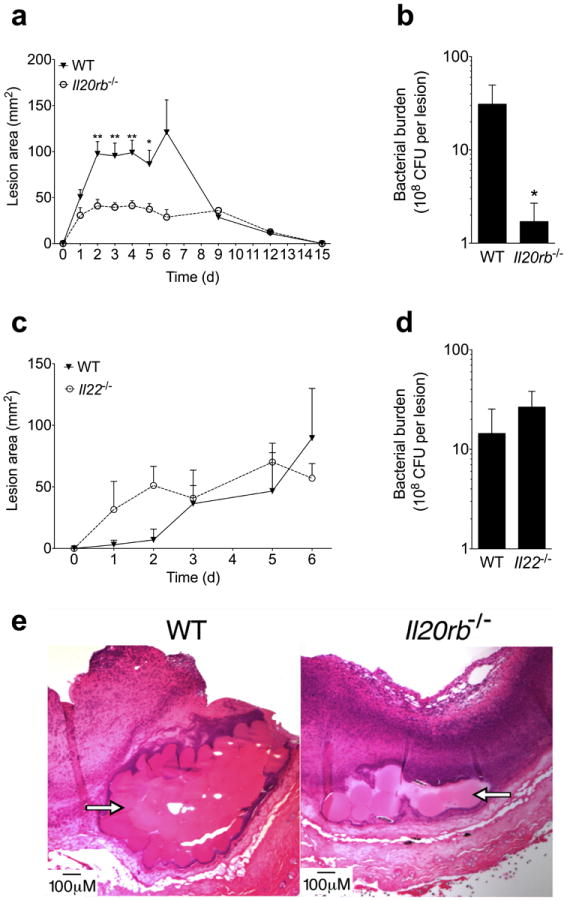

To determine if the IL-20R cytokines influenced the host response to S. aureus skin infection, we intradermally infected wild type and Il20rb−/− mice with 107 colony forming units (CFU) of a clinical MRSA isolate (USA 300 LAC strain). We then followed the size of the resultant skin abscesses over 15 days. Il20rb−/− mice developed smaller lesions (Fig. 1a) with decreased bacterial burdens (Fig. 1b). Although IL-22 has documented antimicrobial activities against other mucosal pathogens29,30, Il22−/− mice did not have altered susceptibility to S. aureus skin infection (Fig. 1c-d). Histology confirmed that IL20rb−/− mice had smaller abscesses with preserved skin architecture and a greater influx of inflammatory cells (Fig. 1e), consistent with the critical role of neutrophils in control of cutaneous S. aureus infection1.

Figure 1. IL-20RB-deficiency decreases cutaneous S. aureus infection.

Wild type (WT) and Il20rb−/− mice were infected intradermally with MRSA (USA300). (a) Lesion area over the course of infection. (b) Bacterial colony forming units (CFU) from lesions six days after infection. (c-d) Lesion area and day six bacterial CFU after infection of WT and Il22−/− mice. (e) H&E stain of infected tissue from representative mice six days after infection. Arrows indicate Cytodex beads that were injected with MRSA inoculation and line abscess cavity. Data shown are representative of 3-5 independent experiments, each using at least 5 mice per group, and displayed as mean + s.e.m.

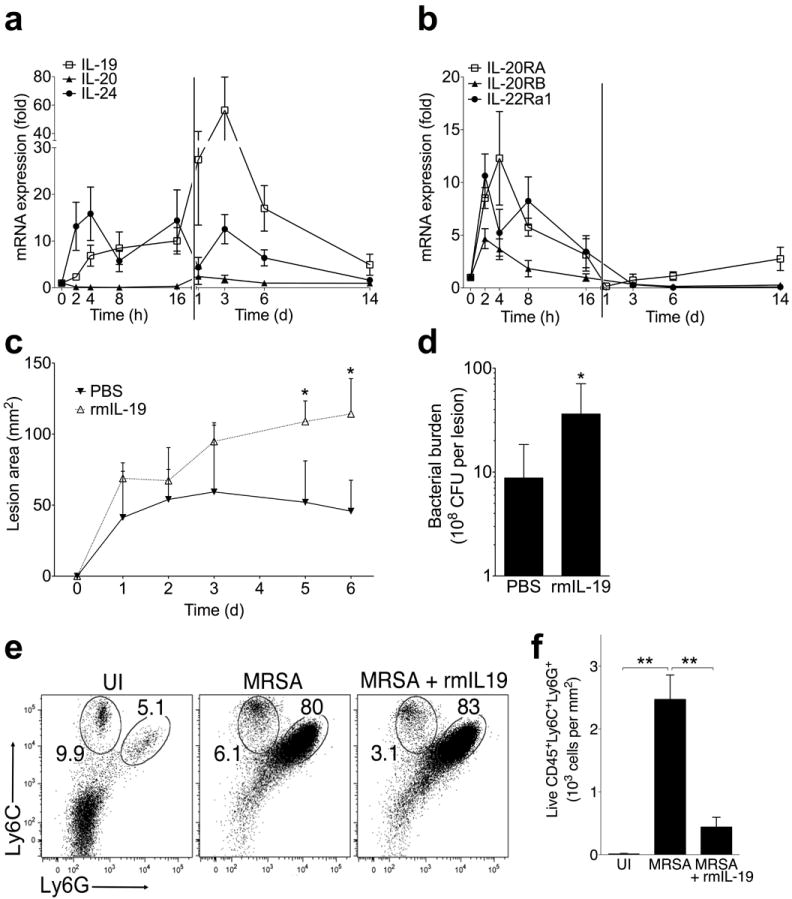

Since IL20RB forms one chain of the receptors that bind IL-19, IL-20, and IL-24, we next established the induction of these cytokines during S. aureus skin infection. Compared to uninfected skin, IL-19 and IL-24 transcript levels increased in infected skin during the initial hours of infection and remained elevated over the course of the infection (Fig. 2a). In contrast, IL-20 was not induced during infection (Fig. 2a). IL20RA and IL20RB, which combine to form a heterodimeric receptor for IL-19, IL-20, and IL-24, were both induced within two hours post-infection with a subsequent return to baseline by day 3 (Fig. 2b). IL22RA1, which heterodimerizes with IL20RB to form a receptor for IL-20 and IL-24 but not IL-19, showed a similar pattern of induction during infection (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. Recombinant IL-20R cytokines increase cutaneous S. aureus infection.

(a-b) mRNA expression in infected tissue compared at indicated time points after MRSA infection of wild type mice. (c-d) Lesion area and bacterial CFU after infection of wild type mice with MRSA suspended in either PBS or recombinant murine IL-19 (rmIL-19, 1 μg per injection). (e) Ly-6G and Ly-6C staining of live CD45+MHCII+ cells in skin from uninfected mice (UI) or mice four days after injection with MRSA, or MRSA + rmIL-19. Neutrophil (Ly6C+Ly6G+) and monocyte (Ly6C+Ly6G-) gate frequencies are shown. (f) Number of Ly6C+Ly6G+ neutrophils in skin from mice analyzed as described in (e). Data shown are representative of 2-4 independent experiments, each using 3-5 mice per group, and displayed as mean + s.e.m. or representative flow cytometry plots.

To corroborate our knockout mouse data suggesting that IL-20R signaling promoted S. aureus skin infection, we injected wild type mice with MRSA resuspended in recombinant IL-20R cytokines. Consistent with our findings in Il20rb−/− mice, injection of recombinant murine IL-19 led to the development of larger lesions (Fig. 2c) and increased bacterial burdens (Fig. 2d). Mice produced IL-24 but not IL-20 in response to S. aureus infection (Fig. 2a). However, because these two cytokines induce a similar epithelial gene signature21 and similarly use both types of IL-20R, we injected mice with recombinant murine IL-20 as a surrogate for IL-24, which is not available commercially. Recombinant IL-20 injection had similar effects on S. aureus infection as recombinant murine IL-19 (Supplementary Fig. 1), consistent with IL-19 and IL-20 both using the type I IL-20 receptor. Although we cannot rule out unique effects of IL-24, the results of recombinant IL-20 treatment also suggest that type II IL-20R signaling did not alter the observed susceptibility conferred by type I IL-20R signaling. Analysis of infected skin revealed an inflammatory infiltrate primarily composed of neutrophils (Ly6C+Ly6G+) (Fig. 2e). Recombinant IL-19 did not substantially affect the relative composition of cells in infected tissue (Fig. 2e), but strikingly reduced their absolute numbers (Fig. 2f). Taken together, these results show that the IL-20R cytokines were induced by S. aureus skin infection and impaired the inflammatory response required for optimal host defense.

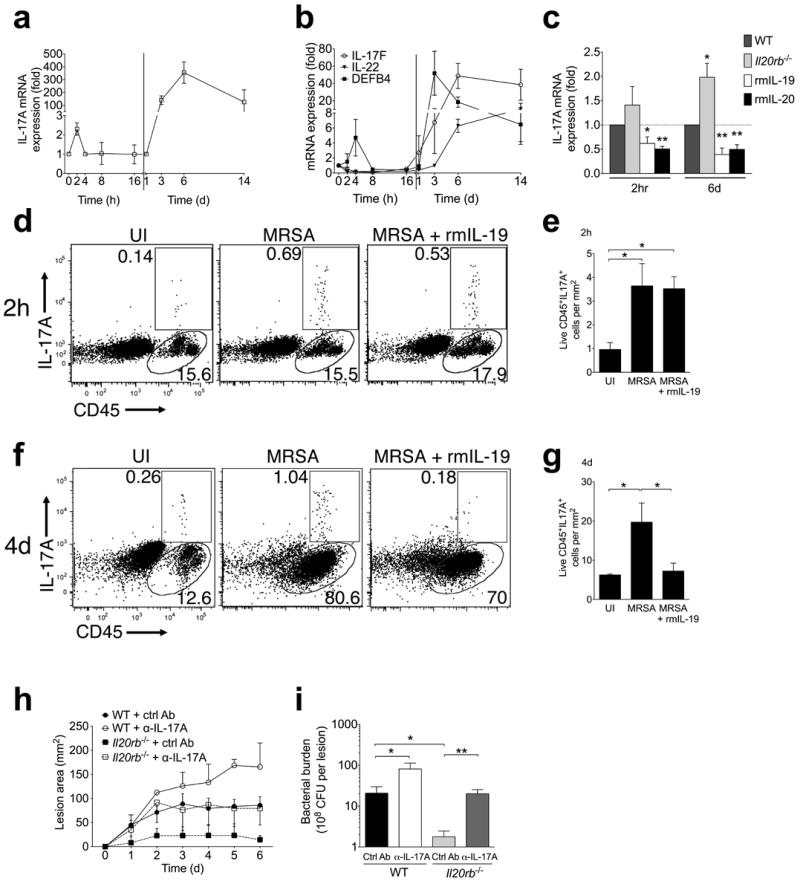

IL-20R cytokines inhibit IL-17A response to S. aureus

Consistent with prior literature indicating a critical role for γδ T cell-derived IL-17A in neutrophil recruitment and protection against cutaneous S. aureus infection14, we found transiently increased IL-17A transcript levels in infected skin early after infection (Fig. 3a). IL-17A expression then dramatically increased by three days after infection and remained elevated through at least day 14 (Fig. 3a). Defensin beta 4 (DEFB4), an anti-staphylococcal peptide induced by IL-17A31, followed the observed early and late kinetics of IL-17A expression (Fig. 3b). IL-17F and IL-22, cytokines commonly associated with IL-17A responses, only appeared later during the course of infection (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. IL-20R signaling suppresses IL-17A response to S. aureus infection.

(a-b) mRNA expression in infected skin compared to uninfected control at indicated time points after MRSA infection. (c) IL-17A mRNA expression compared to uninfected control two hours and six days after infection in wild type (WT), Il20rb−/−, or recombinant cytokine-treated wild type mice. (d-g) IL-17A and CD45 staining of live cells from ear skin of wild type mice two hours after injection (d-e) or flank skin of wild type mice four days after injection (f-g) with PBS (uninfected, UI), MRSA, or MRSA + rmIL-19. Representative plots (d, f) and absolute cell numbers from replicate mice (e, g) are shown. (h-i) Lesion size and bacterial CFU (six days after infection) in wild type (WT) or Il20rb−/− mice injected with control or IL-17A-neutralizing antibody (α-IL-17A) at the time of MRSA inoculation. Data shown are representative of 2-4 independent experiments, each using 3-5 mice per group, and displayed as mean + s.e.m. or representative flow cytometry plots.

We hypothesized that alterations in IL-17A production contributed to the increased susceptibility to S. aureus conferred by IL-20R signaling. Consistent with this, we found that treatment with recombinant IL-19 or IL-20 significantly inhibited IL-17A expression in skin two hours after infection and this inhibition persisted at six days (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, Il20rb−/− mice showed a trend toward increased IL-17A expression two hours after infection that became significant by six days (Fig. 3c). IL-17F, IL-22, and interferon (IFN)-γ expression were not altered by IL-20R stimulation or deficiency (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Expression of the anti-microbial products DEFB4 and S100a9 was consistent with their known induction by IL-17A, but induction of S100a8 by recombinant IL-19 treatment suggested alternative regulation of this gene (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Flow cytometry of skin cells early and late after infection confirmed induction of IL-17A+ cells (Fig. 3d-g). Reduction in the number of IL-17A+ cells in infected tissue after recombinant IL-19 treatment was apparent four days after infection (Fig. 3f-g). Consistent with prior reports14, the IL-17A+ cells induced in infected skin were predominantly γδ T cells (Supplementary Fig. 3a-b). These γδ T cells expressed intermediate levels of the γδ TCR (Supplementary Fig. 3a-b), in accordance with the reported capacity of dermal (γδ TCRint) rather than epidermal (γδ TCRhi) γδ T cells to secrete IL-17A32. To determine if increased IL-17A explained the protection conferred by Il20rb-deficiency, we injected neutralizing antibody against IL-17A into the inoculum at the time of MRSA infection. This abrogated the difference in lesion size (Fig. 3h) and bacterial burden (Fig. 3i) seen in Il20rb−/− mice treated with control antibody, confirming IL-17A-dependent protection in the Il20rb−/− mice. However, administration of anti-IL-17A led to more severe infection in wild type mice than Il20rb−/− mice (Fig. 3h-i), indicating the presence of additional IL-17A-independent protective mechanisms in the knockout mice. Taken together, these experiments show that suppression of IL-17A by IL-20R cytokines contributes to their negative impact on control of S. aureus skin infection.

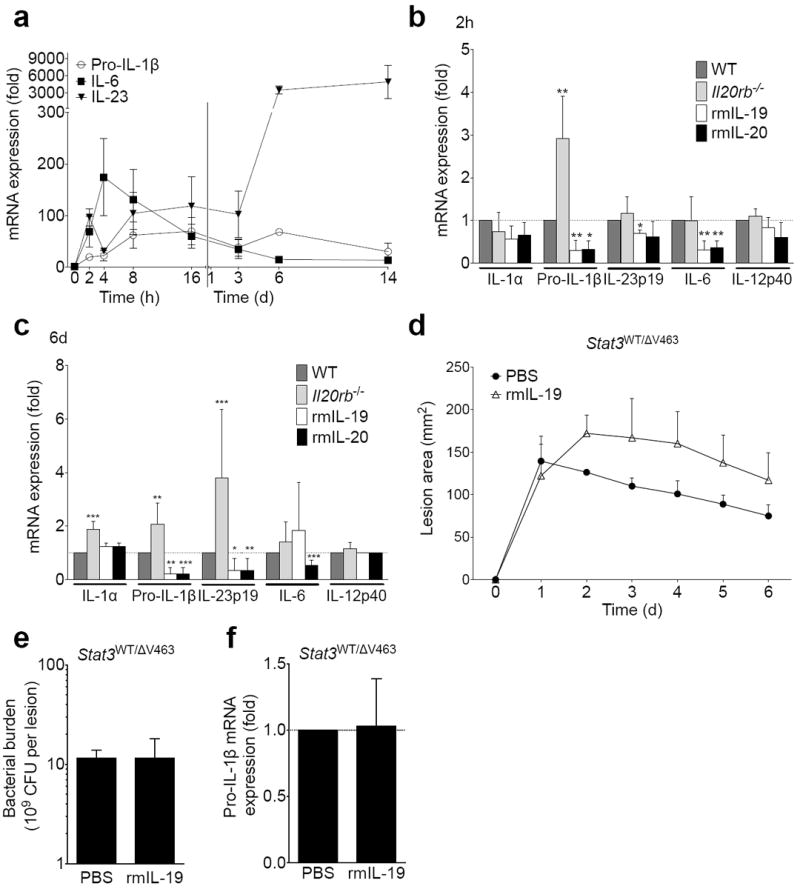

IL-20R cytokines inhibit transcription of pro-IL-1β

Since type I and type II IL-20R complexes do not appear to be expressed on lymphocytes19,33, we hypothesized that the decrease in IL-17A seen after exposure to IL-20R cytokines reflected an effect on the IL-17A-inducing cytokines produced by IL20RB-expressing keratinocytes and myeloid cells19. Whereas IL-6 is critical for IL-17A induction in CD4+ T cells34, IL-1β and IL-23 are major inducers of IL-17A from γδ T cells35. IL-1β can further feed back onto keratinocytes to enhance IL-23 expression36. Expression of pro-IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23 was induced within hours of S. aureus skin infection (Fig. 4a). Compared to wild type mice, Il20rb−/− mice displayed increased pro-IL-1β mRNA expression two hours after infection (Fig. 4b). Treatment of wild type mice with recombinant IL-19 or IL-20 suppressed S. aureus-induced pro-IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-23 at this time point (Fig. 4b). By the peak of infection on day six, IL-20R signaling continued to have similar effects on pro-IL-1β expression, and the effects on IL-23 became more pronounced (Fig. 4c). The broader and more pronounced effect on cytokine expression seen with recombinant IL-20R cytokine treatment compared to IL20RB-deficiency may reflect compensatory mechanisms operating in the knockout mice or a difference between the physiologic amount of these cytokines in vivo and our selected treatment dose. Overall, suppression of pro-IL-1β expression seemed to be the earliest and most consistent effect of IL-20R signaling on these IL-17A-inducing cytokines. Consistent with a reported dependence of IL-20R signaling on STAT3, transgenic mice with a mutation in Stat3 (ΔV463) that models STAT3 dysfunction in human Job’s syndrome failed to respond to recombinant murine IL-19 as measured by lesion size, bacterial burden, and IL-1β expression after S. aureus infection (Fig. 4d-f).

Figure 4. IL-20R cytokines suppress pro-IL-1β transcription.

(a) mRNA expression in infected tissue compared to uninfected control at indicated time points after MRSA infection of wild type mice. (b) mRNA expression in infected tissue two hours after infection of wild type (WT), Il20rb−/−, or recombinant cytokine-treated wild type mice normalized to WT response. (c) mRNA expression in infected tissue from WT, Il20rb−/−, or cytokine-treated mice six days after infection normalized to WT response. (d-f) Lesion size (d), day six bacterial burden (e), and pro-IL-1β transcript levels (f) in Stat3WT/ΔV463 mice with and without rmIL-19. Data shown are representative of 2-5 independent experiments, each using at least 5 mice per group, and displayed as mean + s.e.m.

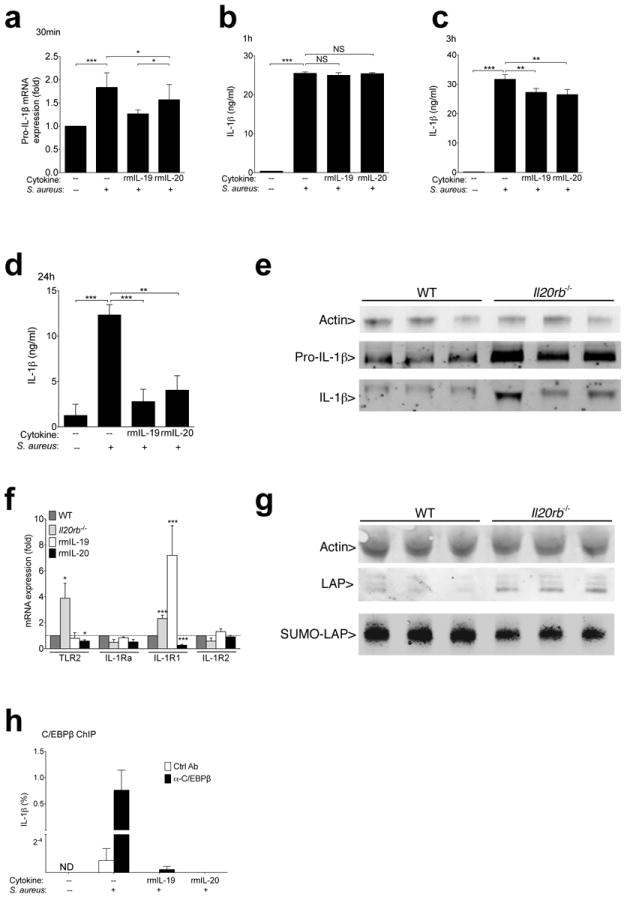

The ability of IL-1β to positively regulate its own transcription37 suggests the observed early changes in pro-IL-1β mRNA may have reflected direct effects of IL-20R cytokines on inflammasome-mediated post-translational processing of pro-IL-1β into IL-1β. However, exposure to IL-20R cytokines inhibited pro-IL-1β transcript induction in a mouse keratinocyte cell line (PAM 2-12) within thirty minutes of S. aureus exposure (Fig. 5a). Differences in IL-1β protein concentration could not be detected until three hours and became more pronounced by 24 hours (Fig. 5b-d), indicating that IL-20R cytokines directly altered pro-IL-1β transcription before any changes in post-translational processing affected levels of mature IL-1β protein. To detect mature IL-1β protein, which is indistinguishable from pro-IL-1β by available ELISA and flow cytometry antibodies, we used immunoblotting and confirmed increased expression of both pro- and cleaved IL-1β in IL20rb−/− compared to wild type primary keratinocyte cultures after 24 hours of MRSA exposure (Fig. 5e).

Figure 5. IL-20R signaling sumoylates C/EBPβ, a transcriptional regulator of IL-1β.

(a) Pro-IL-1β mRNA expression in PAM 2-12 mouse keratinocytes cultured for 30 minutes with 50:1 ratio of S. aureus (Wood46 strain bioparticles) with or without 15 minute pre-exposure to indicated cytokines. (b-d) IL-1β detected by ELISA in supernatants of PAM 2-12 keratinocytes after 1 hour (b), 3 hours (c), or 24 hours (d) of S. aureus exposure (Wood46 strain bioparticles). (e) Pro-IL-1β (31 kDa) and IL-1β (17 kDa) detected by immunoblot of wild type and Il-20rb−/− primary keratinocyte lysates after 24 hours of live MRSA USA300 exposure. Each lane shows lysates derived from an individual mouse. To optimally visualize actin (42 kDa), samples were run on a separate gel loaded with less protein. (f) Wild type (WT), Il20rb−/−, or recombinant cytokine-treated (rmIL-19 or rmIL-20) wild type mice were infected with MRSA. Tissue was harvested, and transcript levels were compared to wild type mice two hours after infection. (g) Immunoblot of actin (42 kDa) and C/EBPβ (LAP) (35-39 kDa) in primary keratinocyte lysates after 30 minutes of exposure to live MRSA. Anti-SUMO2/3 immunoprecipitates from the same cell lysates were run on a separate gel loaded with higher protein concentrations to detect SUMO associated LAP (SUMO-LAP). Each lane represents an individual mouse. (h) Relative chromatin binding of CEBP/β at IL-1β promoter in PAM 2-12 keratinocytes after incubation with or without MRSA and recombinant cytokines. Binding is displayed as percent of input DNA after immunoprecipitation with CEBP/β or isotype control antibody. Data shown are representative of 2-5 independent experiments, each using at least 3 mice per group (e-g) or replicate cell cultures (a-d, h), and displayed as mean + s.e.m. ND, not detected. NS, not significant.

These data indicated that the effect of IL-20R cytokines on pro-IL-1β was too rapid to be mediated by transcriptional regulation of molecules that control pro-IL-1β expression. Indeed, expression of molecules that regulate pro-IL-1β expression, such as Toll-Like Receptor 2 (TLR2), IL-1R antagonist (IL-1Ra), stimulatory IL-1R1, or inhibitory IL-1R2, was not modulated during S. aureus infection by loss or gain of IL-20R signaling in a manner that fully explained the observed effects on IL-1β expression (Fig. 5f). Transcriptional control of pro-IL-1β is also known to involve CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein β (C/EBPβ), activity of which can be rapidly regulated by post-translational modification and influences transcription of many inflammation-associated cytokines38,39. Total amounts of the active isoform of C/EBPβ (Liver Activating Protein, LAP) appeared slightly increased in S. aureus-stimulated keratinocytes from Il20rb−/− mice compared to wild type mice (densitometry readings over background: 2.09 ± 0.2 versus 0.99 ± 0.3; p=0.03. Densitometry readings for actin were not significantly different between groups) (Fig. 5g). After immunoprecipitation of proteins containing the inhibitory small-ubiquitin-related modifier (SUMO), lower amounts of C/EBPβ were detected in Il20rb−/− keratinocytes than wild type (densitometry 41.36 ± 0.6 versus 45.47 ± 1; p=0.02) (Fig. 5g), indicating a reduced capacity in the presence of IL-20R signaling for C/EBPβ to induce transcription of pro-inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β. Consistent with this, immunoprecipitation of C/EBPβ revealed that IL-20R cytokine treatment of keratinocytes inhibited S. aureus-induced DNA binding by C/EBPβ at the IL-1β locus (Fig. 5h). In sum, these results suggest that IL-20R cytokines inhibit pro-IL-1β transcription by mechanisms that involve STAT3 and the post-translational inactivation of C/EBPβ.

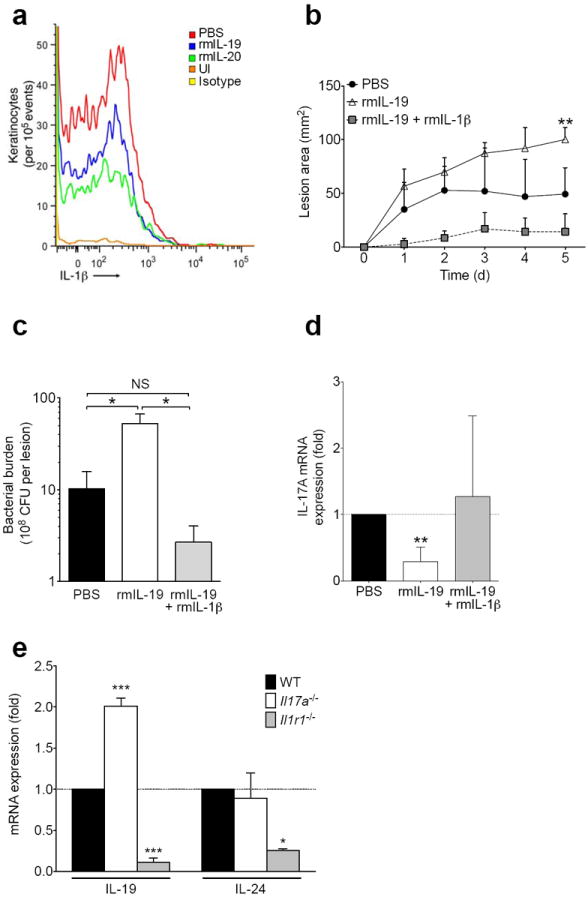

IL-1β rescues IL-20R-induced S. aureus susceptibility

The above studies on keratinocyte cell lines and primary keratinocytes were consistent with direct action of IL-20R cytokines on keratinocytes. IL-20R cytokine treatment also inhibited IL-1β protein induction in vivo in keratinocytes at the S. aureus abscess site on day 3 of infection (Fig. 6a). Recombinant murine IL-1β administration at the time of S. aureus inoculation overcame the effects of recombinant murine IL-19 on lesion size (Fig. 6b), bacterial load (Fig. 6c), and IL-17A mRNA expression (Fig. 6d). Mice deficient in IL-1R1, but not IL-17A, did not upregulate IL-19 or IL-24 in response to S. aureus infection (Fig. 6e), suggesting that IL-20R cytokines act as an inhibitory feedback mechanism triggered by IL-1β Taken together, these results suggest IL-20R signaling increased SUMO-inactivation of C/EBPβ, leading to the observed decrease in pro-IL-1β transcription and subsequent failure to activate downstream inflammatory events, including IL-17A induction, that have been shown to be critical for the neutrophil recruitment needed for control of S. aureus.

Figure 6. Recombinant IL-1β rescues IL-20R cytokine-induced susceptibility to S. aureus.

(a) IL-1β expression in live CD104+ keratinocytes detected by flow cytometry of single cell suspensions from infected skin tissue three days after MRSA infection with or without (PBS) recombinant murine cytokine (rmIL-19, rmIL-20) treatment. Staining of uninfected skin (UI) and staining with isotype control antibody also shown. (b-d) Wild type mice were inoculated with MRSA in PBS, rmIL-19, or rmIL-19 + rmIL-1β and assessed for lesion size (b), bacterial burden (c), and IL-17A mRNA (d). (e) IL-19 and IL-24 mRNA expression in Il17a−/−and Il1r1−/− mice, normalized to wild type (WT) mice, six days after infection with MRSA. Data shown are representative of 2-3 independent experiments, using at least 3-5 mice per group each time, and displayed as mean + s.e.m.

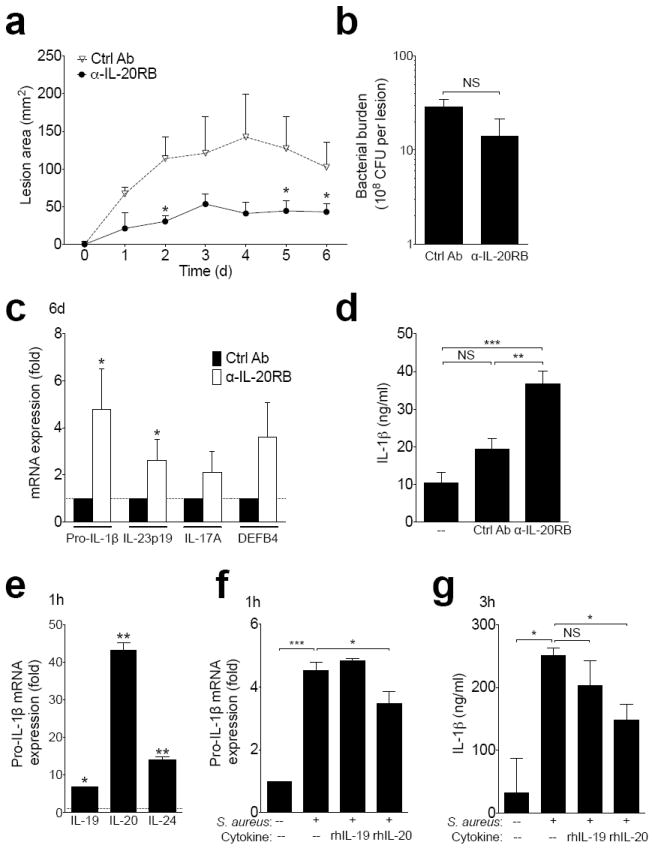

IL-20RB blockade holds therapeutic potential for humans

To assess the potential therapeutic effect of blocking IL-20R signaling during S. aureus infection, we included an IL-20RB antibody in the S. aureus inoculum at the time of infection. This single dose of antibody significantly reduced lesion size and showed a trend toward reduced bacterial burden (Fig. 7a-b), corroborating the phenotypes seen in knockout and recombinant cytokine-treated mice and highlighting the therapeutic potential of optimized targeting of the IL-20R cytokine pathway. Anti-IL-20RB most prominently augmented pro-IL-1β induction (Fig. 7c), consistent with the effects of IL-20R cytokines presented above. Similar to its effects in vivo, anti-IL-20RB also enhanced IL-1β production when applied directly to PAM2-12 mouse keratinocytes (Fig. 7d). To evaluate if the effects of IL-20R cytokines may be relevant to humans, we derived primary keratinocyte cultures from human foreskin samples. Within one hour of S. aureus exposure, human keratinocytes upregulated all of the IL-20R cytokines (Fig. 7e). In contrast to mice, human keratinocytes expressed IL-20 at higher levels than IL-19 and IL-24. This species-specific induction pattern was reflected in the ability of recombinant human IL-20, but not recombinant human IL-19, to mirror its murine effects and inhibit induction of IL-1β mRNA and protein by S. aureus in primary human keratinocytes (Fig. 7f-g). These data suggest that IL-20R blockade may hold therapeutic potential for patients with recurrent or severe MRSA skin infections.

Figure 7. IL20R cytokines are induced by S. aureus in human keratinocytes and can be therapeutically blocked in the murine skin infection model.

(a-c) Wild type mice infected with MRSA in the presence of anti-IL-20RB or isotype control antibody. Lesion size (a), day six bacterial burden (b), and mRNA expression in infected tissue six days after infection (c). (d) IL-1β in PAM 2-12 keratinocyte supernatants 24 hours after incubation with S. aureus and anti-IL20RB or control antibody. (e-g) Primary human keratinocytes were derived from foreskin. IL-20R cytokine mRNA expression in cells one hour after culture with MRSA compared to uninfected controls (e). Pro-IL-1β mRNA expression one hour after incubation with MRSA and recombinant human (rh) IL-19 or rhIL-20 compared to uninfected controls (f). Supernatant IL-1β 3 hours after incubation with MRSA and recombinant cytokines (g). Data shown are representative of 2-3 independent experiments, each using 3-5 mice per group, or at least 3 individual foreskin samples, and displayed as mean + s.e.m.

DISCUSSION

Our data identify the capability of IL-20R cytokines to promote S. aureus skin infection. To our knowledge, this is the first description of the role of these cytokines during infection. We show that this ability to promote infection is due to suppression of antimicrobial inflammatory pathways, characterizing the anti-inflammatory properties of these cytokines during host defense.

Anti-inflammatory properties are consistent with the tissue restorative functions ascribed to IL-20R cytokines and befit their relatedness to the prototypical anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10. However, an immunosuppressive role for these cytokines may seem paradoxical in light of the ability of IL-20R cytokine overexpression to drive psoriasis-like disease in mice23,24. This paradox is perhaps explained by distinguishing two distinct characteristics of psoriasis: epithelial proliferation, consistent with known actions of these cytokines, versus inflammation, which may be driven by other pathways. The dependence of IL-20R cytokine induction on IL-1R signaling during S. aureus infection in our studies, and previous reports documenting induction by inflammatory mediators such as IL-1β and IL-17A40,41, suggests their anti-inflammatory activities may serve as a mechanism for feedback inhibition. Indeed, previous work has suggested an immunoregulatory role for IL-19 in colitis42,43, and we have now uncovered an inhibitory function of these cytokines on IL-1β -driven inflammation during infection. It remains unclear if the detection of IL-20R cytokines in autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis44-46 reflects an etiologic role or an ineffective feedback pathway triggered by inflammation. Regardless, our results suggest that these cytokines have immunosuppressive properties that may contribute to infection susceptibility in a variety of contexts.

Our findings define the sequence of events triggered by IL-20RB signaling that promote S. aureus skin infection. IL-1β induction after recognition of S. aureus by TLR2, NOD, and other pattern recognition receptors is critical for triggering the inflammatory response, including the IL-17A-dependent recruitment of neutrophils required for clearance of infection1. We show that IL-20RB signaling acts in a STAT3-dependent manner to interfere with this early induction of IL-1β and related inflammatory cytokines, rapidly increasing post-translational sumoylation of the transcription factor C/EBPβ that leads to its decreased binding at the IL-1β promoter. The central role of C/EBPβ in transcribing a number of inflammatory cytokines38,39 suggests that this mechanism is a major contributor to the anti-inflammatory consequences of IL-20RB signaling.

IL-19 and IL-24, but not IL-20, were induced in mouse skin by S. aureus infection, a similar pattern to what has been described for induction by inflammatory cytokines such as IL-2347. The differential regulation of these related cytokines remains to be elucidated, but based on their known expression pattern, it is likely that during infection they are induced in keratinocytes and resident innate immune cells. We show that these cytokines can act on keratinocytes, known to express type I and type II IL-20R, to suppress IL-1β expression. Similar effects likely occur in other IL-20R-expressing resident cell populations, including myeloid cells. Specific effects of IL-24, which signals through both type I and type II IL-20R, could not be tested because of commercial unavailability of the recombinant cytokine. However, the similar receptor usage of IL-20 and IL-24 allowed us to use recombinant murine IL-20 to assess the contribution of type II IL-20R signaling, which is not engaged by IL-19. Treatment with either recombinant IL-19 or IL-20 similarly affected infected mice and keratinocytes. This suggests the observed effects are predominantly mediated by the type I receptor complex, although unique effects of IL-20 compared to IL-19 on expression of TLR2 and IL-1R1 expression suggest that type II IL-20R may additionally contribute to the IL-20RB-attributable phenotype observed during S. aureus infection. IL-20 was the major IL-20R cytokine induced by S. aureus from human keratinocytes, suggesting further species differences in regulation of individual members of this family of cytokines.

IL-20R cytokines are closely related to IL-22, and prior studies in reconstituted human epidermis revealed similar induction of antimicrobial peptides and other factors21. However, Il20rb−/− mice did not have altered susceptibility to Citrobacter rodentium colitis, in which IL-22 plays a protective role29. In our studies, IL-22, unlike IL-20R cytokines, was not induced until relatively late in the course of S. aureus infection, a possible contributing factor to its lack of influence on the overall control of infection in this model. Compared to IL-22, IL-20R cytokines generally had modest to negative effects on neutrophil chemoattractant induction in reconstituted human epidermis21, suggesting the suppressive effects on IL-1β and IL-17A predominated the inhibitory effect of IL-20RB signaling on neutrophil recruitment. Such gene expression differences in response to IL-22 and the individual IL-20R cytokines21 suggest unique aspects of signaling by each of these cytokines despite their common activation of STAT3, a finding consistent with the inability of IL-6, which also signals through STAT3, to suppress S. aureus-induced IL-1β production in mouse keratinocytes (data not shown). Thus, although IL-22 and IL-20R cytokines may share some properties related to STAT3 activation, epithelial proliferation, and wound healing, they appear to have distinct immunologic functions. IL-22 enhances direct anti-microbial activity during certain mucosal infections, whereas IL-20R cytokines suppress host defense mechanisms by invoking anti-inflammatory pathways.

Our identification of the immunosuppressive effects of IL-20R cytokines in the context of S. aureus skin infection uncovers their potential to act as anti-inflammatory mediators. This activity may contribute to their effects on epithelial proliferation and wound healing. However, it also identifies them as potentially important inhibitors of inflammatory pathways involving IL-1β, IL-23, and IL-17A, suggesting augmentation of IL-20R signaling as a potential therapy for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Such augmentation, however, may predispose to infection susceptibility. This raises the possibility that intrinsic susceptibility to S. aureus infection, such as in atopic dermatitis and select immunedeficiencies, may reflect overly exuberant IL-20R signaling that could be modulated for therapeutic benefit.

ONLINE METHODS

Materials

Chemical reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company, St. Louis, MO. Blood agar plates were from Thermo Scientific, Dubuque, IA. Tryptic Soy Broth was from General Laboratory Products, Yorkville, IL. Fetal Bovine Serum was from Thermo Scientific, Dubuque, IA.

Mice

Wild type C57BL/6 and Il1r1−/− mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME. Il20rb−/− and Il22−/− mice (C57BL/6 background) were generated as previously described29. Il17a−/− mice were a gift from Y. Iwakura (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan). Stat3WT/V463 transgenic mice expressing two copies of a mutated Stat3 (V463 deletion commonly found in dysfunctional STAT3 in human Job’s syndrome) were a gift from J. O’Shea (NIAMS, NIH, Bethesda, MD; manuscript in preparation). Mice were 7-12 weeks old during the course of the experiments and were age- and gender-matched within each experiment. Sample size was chosen based on prior experience with experimental variability. There was no additional randomization or blinding of evaluations. All experiments were done in compliance with the guidelines of the NIAID Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Infections

The clinical isolate of MRSA USA300 (LAC strain) was a gift from F. DeLeo (Rocky Mountain Labs, NIAID). MRSA was diluted to 109 CFU/ml in PBS. 100 μl was then added to 520 μl of PBS and 380 μl of Cytodex beads (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), diluted per manufacturer instructions. Unless otherwise indicated, 100 μl (107 CFU) of the MRSA suspended in PBS and Cytodex beads (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) (or PBS and beads alone) was injected intradermally into the shaved back of each mouse. Each day the resultant lesions were measured at the mid-point intersection for length and width using electronic calipers (Mitutoyo America Corporation, Aurora, IL). The area was determined by multiplying length and width and tracked over six to fifteen days. To allow optimal recovery of tissue two hours after inoculation, intradermal injections into the ear were used for these short-term experiments by suspending MRSA at 109 CFU/ml in PBS and injecting 10 μl into each ear; uninfected mice were bilaterally injected with PBS alone. For neutralizing antibodies, 100 μg anti-IL-17A (clone 17FE, BioXcell, West Lebanon, NH), anti-IL-20RB (clone 20RNTC, eBiosciences), or IgG1 isotype antibodies (MOPC-21, BioXcell) were injected with MRSA in 100 μl total volume per mouse. For recombinant cytokines, the MRSA inoculum was combined with recombinant murine IL-1β IL-19, or IL-20 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at a final concentration of 1 μg/100 μl injection for the flank, or 100 ng/10 μl injection for the ear.

Skin Bacteria Burden

A 3 mm punch biopsy of the center of the infected area was taken and the skin was homogenized with a Tissue Lyser II (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for 7 min at full speed. Serial dilutions were made in PBS and plated on blood agar to determine the number of CFU per biopsy, and the CFU per lesion was calculated by multiplying the CFU per unit area by the corresponding lesion area.

Histology

Skin samples were surgically removed, placed in Histocette containers (Thermo Scientific), and then placed in 10% formalin (Thermo Scientific) for 36 hours. The samples were then moved to a 70% EtOH solution. Histoserv, Inc (Germantown, MD) performed the tissue processing. Images were taken at 100x magnification with a BX61 microscope (Olympus, Center Valley, PA).

Flow Cytometry

Ears were surgically removed two hours after injection with MRSA or PBS. Alternatively, flank abscess tissue was taken at various points during infection. Whether from ear or flank, skin processing and staining was performed as previously described48. Total cellular recovery was assessed using microscopy and trypan blue (Invitrogen). Cellular markers of interest were analyzed after gating on live (LIVE/DEAD®, Invitrogen) cells with exclusion of debris and doublets. All antibodies were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA) and used per manufacturer instructions. Signal acquisition was performed on an LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences), and data analyzed with FlowJo 9.5.2 (Treestar, Ashland, OR).

RNA Isolation

Skin samples were surgically removed, placed in RNA later (Ambion, Foster City, CA) and stored at -80°C. The samples were placed in 2 ml Safe-Lock tubes (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY) along with one stainless steel ball bearing (Qiagen) and run through the TissueLyser II (Qiagen) for 6 min at full speed in 300 μl of RLT Buffer (Qiagen). Then, RNA was extracted using the Fibrous Tissue RNAeasy Kit (Qiagen) per manufacturer instructions. RNA yield was measured on a NanoDrop ND-1000. RNA was stored at -80°C until analyzed by PCR as previously described9.

Real Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA was prepared using Taqman One-Step RT-PCR Master Mix instructions (Life Technologies). All samples were analyzed on a 7500-fast Real-Time PCR System (Life Technologies) as previously described9. Mouse primers were all purchased from Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies: IL-17A (Mm00439619_m1*), IL-17F (Mm00521423_m1*), IL-22 (Mm00444241_m1), DefB4 (Mm00731768_m1*), IL-19 (Mm01288324_m1*), IL-20 (Mm00445341_m1*), IL-24 (Mm00474102_m1*), IL-20RA (Mm00555504_m1*), IL-20RB (Mm01232398_m1*), IL-22Ra1 (Mm01192943_m1*), IL-12(p40) (Mm99999067_m1), interferon gamma (Mm01168134_m1*), IL-1β (Mm01336189_m1*), IL-6 (Mm00446190_m1*), IL-23(p19) (Mm00518984_m1*), TLR2 (Mm00445212_m1*), IL-1Ra (Mm00446186_m1*), IL-1R1(Mm00434237_m1*), IL-1R2 (Mm00439629_m1*), Beta-defens in 4 (Mm01184338_m1*), S100a8 (Mm00496696_g1*), and S100a9 (Mm00656925_m1*). Human probes were also purchased from Life Technologies for IL-19 (Hs00604657_m1*), IL-20 (Hs00218888_m1*), IL-24 (Hs01114274_m1*), and IL-1β (Hs01555410_m1*). mRNA expression from infected skin was compared to uninfected skin from naïve mice, or an infected wild type control as indicated, using the ΔΔCT method.

In vitro Keratinocyte Cultures

The PAM 2-12 mouse keratinocyte cell line was a gift from A. Costanzo and J. Jameson (Scripps Research Institute, San Diego, CA). Cells were grow in 75 ml flasks (BD Falcon, Bedford, MA) in PAM media consisting of DMEM (Gibco Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), 10% FBS, Hepes buffer (Thermo Scientific), non-essential amino acids (Gibco), penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco), sodium pyruvate (Gibco), 2-mercapto-ethanol (Gibco), and 50 μg/ml gentamycin (Gibco). Primary keratinocyte cultures were obtained using shaved skin samples floated in dispase (Invitrogen) overnight at 4°C. Cells were scraped into KGM media (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) in BIOCOAT tissue culture plates (Becton Dickerson, Bedford, MA). Human keratinocyte cultures were derived from single cell suspensions of the epidermis from foreskin samples (gift from A. Coxon, NCI, NIH). Skin samples were washed and placed in dispase (Invitrogen) overnight at 4°C. The following day the dermal layer was removed and discarded. The epidermis was placed in 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (Gibco) at 37 degrees for 15 minutes. Cells were then added to a 10% FBS solution to stop the trypsin reaction, pelleted, re-suspended in KCSFM (Invitrogen), and grown in T75 flasks (BD Bioscience) until 70% confluent before preparation for challenge. When confluent for PAM cells, or near confluent for primary cells, the cells were liberated from culture by incubating 8 minutes at 37°C in the presence of 1-2 ml trypsin (Life Technologies) per well or flask. 40 ml of media containing 10% FBS was added to stop the trypsin reaction. The cells were centrifuged at 400g for 8 minutes and then resuspended in 50 ml PBS. Cells were counted (Countess, Life Technologies), centrifuged at 400g for 8 minutes, and then the pellet resuspended to 106/ml media. 2×106 cells were added to each well of a 12 well plate (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY) and incubated at 37°C for 4 hours until adherent.

In vitro Keratinocyte Infection

108 CFU of USA300 MRSA were added to each well and placed at 37°C for up to 24 hours. For ELISA experiments, S. aureus Wood46 strain bioparticles (Life Technologies) were used to avoid non-specific antibody binding by USA300 protein A expression. USA300 was used for all other experiments. After supernatant collection, 600 μl of RLT buffer (Qiagen) was added to the culture wells and mRNA was extracted from the cellular lysate using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen). For cultures involving recombinant cytokines, recombinant IL-19 or IL-20 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) was added directly to the media 15 minutes prior to MRSA exposure. Primary cells were infected in a similar manner with the exception that KGM media (Lonza) was replaced with KBM media (Lonza) 6 hours before MRSA exposure. Cells were liberated in an identical manner as described for PAM cells, and pelleted before exposure to RIPA buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) with protease inhibitor cocktail (SIGMA, St Louis, MO) and phenylmethanesulfanyl fluoride (Fluka St Louis, MO) per manufacturer instructions.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

PAM 2-12 cells were incubated for 30 minutes with MRSA preceded by 15 minutes pre-incubation with or without recombinant cytokines. Precipitation of cell lysates with anti-C/EBPβ (clone E299, AbCam, Cambridge, MA) was performed as previously described49. The IL-1β locus at the C/EBPβ binding site was amplified by qPCR using previously described primers50 (5’-TCAGGAACAGTTGCCATAGC-3’; 3’-AGACCTATACAACGGCTCCT-5’; Applied Biosystems). qPCR was performed using SYBR green (Life Technologies) per manufacturer instructions and compared to input DNA.

Immunoblot

Cell lysates were run on NuPAGE 10% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in MOPS Buffer (Invitrogen) on a VWR Accupower (VWR, Randor, PA) at 110 volts. Transfer from gel to blot membrane was performed using the iBlot gel transfer stack nitrocellulose system (Invitrogen) per manufacturer instructions. Antibodies to actin (clone 13E5, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) or IL-1β (catalog number AF-401-NA, R&D, Minneapolis, MN) were added, followed by fluorescent secondary antibodies (LiCor, Lincoln, NE). Immunoprecipitation of primary cell lysates was performed with EZ-MAGNA chip kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) and anti-SUMO2/3 (catalog number AP1224a, Abgent, San Diego, CA) per manufacturer instructions. Anti-C/EBPβ was purchased from AbCam (clone E299). Band visualization was performed using the Odyssey system (LiCor).

Statistics

Means were compared using two-tailed unpaired t test, or ANOVA for comparison of multiple samples, with Prism software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). NS = not significant, * = p <0.05, ** = p<0.01, *** = p<0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIAID. We thank F. DeLeo (Rocky Mountain Laboratories, NIAID, NIH) and J. O’Shea (NIAMS, NIH) for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

I.A.M. designed, performed, and analyzed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. N.M.F., P.A.V., and P.J.V. assisted with experiments. S.N. and Y.B. assisted with skin flow cytometry acquisition and analysis. W.O. provided Il20rb−/− and Il22−/− mice. S.K.D. oversaw design and analysis of the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. All authors critically read the manuscript. W.O. is an employee of Genentech Inc.;

all other authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Miller LS, Cho JS. Immunity against Staphylococcus aureus cutaneous infections. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:505–518. doi: 10.1038/nri3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waters AE, et al. Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in US Meat and Poultry. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:1227–1230. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rizek CF, et al. Identification of Staphylococcus aureus carrying the mecA gene in ready-to-eat food products sold in Brazil. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2011;8:561–563. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Z, et al. Diagnosis of BK viral nephropathy in the renal allograft biopsy: role of fluorescence in situ hybridization. The Journal of molecular diagnostics : JMD. 2012;14:494–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tong SY, Chen LF, Fowler VG., Jr Colonization, pathogenicity, host susceptibility, and therapeutics for Staphylococcus aureus: what is the clinical relevance? Seminars in immunopathology. 2012;34:185–200. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0300-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Myles IA, Datta SK. Staphylococcus aureus: an introduction. Seminars in immunopathology. 2012;34:181–184. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0301-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krishna S, Miller LS. Innate and adaptive immune responses against Staphylococcus aureus skin infections. Seminars in immunopathology. 2012;34:261–280. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0292-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassat JE, Skaar EP. Metal ion acquisition in Staphylococcus aureus: overcoming nutritional immunity. Seminars in immunopathology. 2012;34:215–235. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0294-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaidamakova EK, et al. Preserving immunogenicity of lethally irradiated viral and bacterial vaccine epitopes using a radio- protective Mn2+-Peptide complex from Deinococcus. Cell host & microbe. 2012;12:117–124. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holtfreter S, Kolata J, Broker BM. Towards the immune proteome of Staphylococcus aureus - The anti-S. aureus antibody response. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300:176–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim HK, Kim HY, Schneewind O, Missiakas D. Identifying protective antigens of Staphylococcus aureus, a pathogen that suppresses host immune responses. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2011 doi: 10.1096/fj.11-187963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rogers DE, Melly MA. Speculations on the immunology of staphylococcal infections. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1965;128:274–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1965.tb11644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmaler M, Jann NJ, Ferracin F, Landmann R. T and B cells are not required for clearing Staphylococcus aureus in systemic infection despite a strong TLR2-MyD88-dependent T cell activation. J Immunol. 2011;186:443–452. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho JS, et al. IL-17 is essential for host defense against cutaneous Staphylococcus aureus infection in mice. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:1762–1773. doi: 10.1172/JCI40891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miller LS, et al. MyD88 mediates neutrophil recruitment initiated by IL-1R but not TLR2 activation in immunity against Staphylococcus aureus. Immunity. 2006;24:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rigby KM, DeLeo FR. Neutrophils in innate host defense against Staphylococcus aureus infections. Seminars in immunopathology. 2012;34:237–259. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0295-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunz S, et al. Interleukin (IL)-19, IL-20 and IL-24 are produced by and act on keratinocytes and are distinct from classical ILs. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:991–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Commins S, Steinke JW, Borish L. The extended IL-10 superfamily: IL-10, IL-19, IL-20, IL-22, IL-24, IL-26, IL-28, and IL-29. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2008;121:1108–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ouyang W, Rutz S, Crellin N, Valdez P, Hymowitz S. Regulation and Function of the IL-10 Family of Cytokines in Inflammation and Disease. 2011 doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101312. Annual Reviews. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Logsdon NJ, Deshpande A, Harris BD, Rajashankar KR, Walter MR. Structural basis for receptor sharing and activation by interleukin-20 receptor-2 (IL-20R2) binding cytokines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:12704–12709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117551109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sa SM, et al. The effects of IL-20 subfamily cytokines on reconstituted human epidermis suggest potential roles in cutaneous innate defense and pathogenic adaptive immunity in psoriasis. J Immunol. 2007;178:2229–2240. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Romer J, et al. Epidermal overexpression of interleukin-19 and -20 mRNA in psoriatic skin disappears after short-term treatment with cyclosporine a or calcipotriol. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2003;121:1306–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1747.2003.12626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.He M, Liang P. IL-24 transgenic mice: in vivo evidence of overlapping functions for IL- 20, IL-22, and IL-24 in the epidermis. J Immunol. 2010;184:1793–1798. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blumberg H, et al. Interleukin 20: discovery, receptor identification, and role in epidermal function. Cell. 2001;104:9–19. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nograles KE, Krueger JG. Anti-cytokine therapies for psoriasis. Exp Cell Res. 2011;317:1293–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tokura Y, Mori T, Hino R. Psoriasis and other Th17-mediated skin diseases. J UOEH. 2010;32:317–328. doi: 10.7888/juoeh.32.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holland DB, Bojar RA, Farrar MD, Holland KT. Differential innate immune responses of a living skin equivalent model colonized by Staphylococcus epidermidis or Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS microbiology letters. 2009;290:149–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ma Y, et al. Interleukin 24 as a novel potential cytokine immunotherapy for the treatment of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Microbes and infection / Institut Pasteur. 2011;13:1099–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zheng Y, et al. Interleukin-22 mediates early host defense against attaching and effacing bacterial pathogens. Nature medicine. 2008;14:282–289. doi: 10.1038/nm1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aujla SJ, et al. IL-22 mediates mucosal host defense against Gram-negative bacterial pneumonia. Nature medicine. 2008;14:275–281. doi: 10.1038/nm1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kao CY, et al. IL-17 markedly up-regulates beta-defensin-2 expression in human airway epithelium via JAK and NF-kappaB signaling pathways. J Immunol. 2004;173:3482–3491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.5.3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cai Y, et al. Pivotal role of dermal IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells in skin inflammation. Immunity. 2011;35:596–610. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagalakshmi ML, Murphy E, McClanahan T, de Waal Malefyt R. Expression patterns of IL-10 ligand and receptor gene families provide leads for biological characterization. International immunopharmacology. 2004;4:577–592. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bettelli E, et al. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sutton CE, et al. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 induce innate IL-17 production from gammadelta T cells, amplifying Th17 responses and autoimmunity. Immunity. 2009;31:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu FL, et al. Interleukin (IL)-23 p19 expression induced by IL-1beta in human fibroblast-like synoviocytes with rheumatoid arthritis via active nuclear factor-kappaB and AP-1 dependent pathway. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46:1266–1273. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krisinger MJ, et al. Thrombin generates previously unidentified C5 products that support the terminal complement activation pathway. Blood. 2012;120:1717–1725. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-412080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsukada J, Yoshida Y, Kominato Y, Auron PE. The CCAAT/enhancer (C/EBP) family of basic-leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors is a multifaceted highly-regulated system for gene regulation. Cytokine. 2011;54:6–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsukada J, Saito K, Waterman WR, Webb AC, Auron PE. Transcription factors NF-IL6 and CREB recognize a common essential site in the human prointerleukin 1 beta gene. Molecular and cellular biology. 1994;14:7285–7297. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Otkjaer K, et al. IL-20 gene expression is induced by IL-1beta through mitogen-activated protein kinase and NF-kappaB-dependent mechanisms. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2007;127:1326–1336. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tohyama M, et al. IL-17 and IL-22 mediate IL-20 subfamily cytokine production in cultured keratinocytes via increased IL-22 receptor expression. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:2779–2788. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Azuma YT, Nakajima H, Takeuchi T. IL-19 as a potential therapeutic in autoimmune and inflammatory diseases. Current pharmaceutical design. 2011;17:3776–3780. doi: 10.2174/138161211798357845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Azuma YT, et al. Interleukin-19 protects mice from innate-mediated colonic inflammation. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2010;16:1017–1028. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alanara T, Karstila K, Moilanen T, Silvennoinen O, Isomaki P. Expression of IL-10 family cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis: elevated levels of IL-19 in the joints. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology. 2010;39:118–126. doi: 10.3109/03009740903170823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sakurai N, et al. Expression of IL-19 and its receptors in RA: potential role for synovial hyperplasia formation. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:815–820. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kragstrup TW, et al. The expression of IL-20 and IL-24 and their shared receptors are increased in rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthropathy. Cytokine. 2008;41:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan JR, et al. IL-23 stimulates epidermal hyperplasia via TNF and IL-20R2-dependent mechanisms with implications for psoriasis pathogenesis. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2006;203:2577–2587. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naik S, et al. Compartmentalized control of skin immunity by resident commensals. Science. 2012;337:1115–1119. doi: 10.1126/science.1225152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Valdez PA, et al. Prostaglandin E2 suppresses antifungal immunity by inhibiting interferon regulatory factor 4 function and interleukin-17 expression in T cells. Immunity. 2012;36:668–679. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Straccia M, et al. Pro-inflammatory gene expression and neurotoxic effects of activated microglia are attenuated by absence of CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2011;8:156. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.