Abstract

Selenocysteine (Sec) incorporation is an essential process required for the production of at least 25 human selenoproteins. This unique amino acid is co-translationally incorporated at specific UGA codons that normally serve as termination signals. Recoding from stop to Sec involves a cis-acting Sec insertion sequence element in the 3′ untranslated region of selenoprotein mRNAs as well as Sec insertion sequence binding protein 2, Sec-tRNASec, and the Sec-specific elongation factor, eEFSec. The interplay between recoding and termination at Sec codons has served as a focal point in researching the mechanism of Sec insertion, but the role of translation initiation has not been addressed. In this report, we show that the cricket paralysis virus intergenic internal ribosome entry site is able to support Sec incorporation, thus providing evidence that the canonical functions of translation initiation factors are not required. Additionally, we show that neither a 5′ cap nor a 3′ poly(A) tail enhances Sec incorporation. Interestingly, however, the presence of the internal ribosome entry site significantly decreases Sec incorporation efficiency, suggesting a role for translation initiation in regulating the efficiency of UGA recoding.

Keywords: selenocysteine, translation, initiation, SBP2, IRES

The incorporation of selenocysteine (Sec) into nascent selenoproteins represents a deviation from the ‘standard’ genetic code by recoding UGA from a translation termination codon to specify Sec. In eukaryotes, UGA recoding is accomplished by a Sec insertion sequence (SECIS) element in the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of selenoprotein mRNAs. SECIS elements have two conserved motifs: an AUGA (SECIS core) motif on the 5′ side of the stem and an apical AAR motif. Disruption of either of these motifs inhibits Sec incorporation.1 The trans-acting factors SECIS binding protein 2 (SBP2), a Sec-specific translation elongation factor (eEFSec), and Sec-tRNASec are also required for Sec incorporation.2,3 SBP2 interacts with the SECIS core motif4 and the SBP2–SECIS complex recruits eEFSec.5 SBP2 is also thought to function at the level of the ribosome to regulate access of eEFSec–Sec-tRNASec–GTP ternary complex to the A-site.5,6 Aside from SBP2–SECIS-dependent regulation, eEF-Sec is presumed to function similarly to eEF1A.

Several groups have investigated the interplay between Sec incorporation and translation termination.7–11 One facet of the Sec incorporation process suggests, however, that translation initiation may be involved: SECIS elements are likely brought in proximity to initiation factors via the established poly(A) binding protein, eIF4G interaction.12,13 In addition, polysome analysis has shown that a significant portion of endogenous GPX4 mRNA remains associated with the 80S peak in both the presence and the absence of sufficient selenium in contrast to a similarly sized non-selenoprotein mRNA, suggesting a lower rate of initiation.14

Cap-dependent translation initiation is a highly regulated process requiring an array of initiation factors (eIFs). Briefly, the eIF4F complex binds the 5′ cap structure and interacts with the 3′ poly(A) tail via poly(A)-binding protein. This messenger ribo-nucleoprotein recruits the 43S pre-initiation complex containing the 40S ribosomal subunit and several initiation factors, including Met-tRNAi-bound eIF2α. This 43S complex then scans the 5′ end of the mRNA until the appropriate start codon is selected. This results in GTP hydrolysis by eIF2α, initiator tRNA release to the ribosomal P-site, eIF release, and 60S ribosome recruitment to form the 80S ribosome.15 Much of this process can be circumvented by internal ribosome entry sites (IRESs) that are frequently found in viral mRNAs. The intergenic IRES from cricket paralysis virus (CrPV IRES) by passes the requirement for all initiation factors and directly recruits 60S and 40S ribosomal subunits. Additionally, the CrPV IRES occupies the P- and E-sites and initiates translation from the A-site at a GCU codon.16,17

In this report, we investigated the relationship of translation initiation and Sec incorporation using capped or uncapped firefly luciferase Sec incorporation reporter mRNAs containing or lacking a poly (A) tail. Additionally, we utilized a dicistronic luciferase reporter containing a CrPV IRES between Renilla and firefly luciferase cDNAs, the latter possessing a Sec codon and the GPX4 SECIS element in its 3′UTR. We found that Sec incorporation can occur when translation initiation was driven by the CrPV IRES and that Sec incorporation requires neither a capped mRNA nor a poly(A) tail. Polyadenylated mRNAs and IRES-containing mRNAs, however, displayed less efficient Sec incorporation. Thus, Sec incorporation does not require the canonical roles of initiation factors but may yet be influenced by an event at initiation that regulates efficiency.

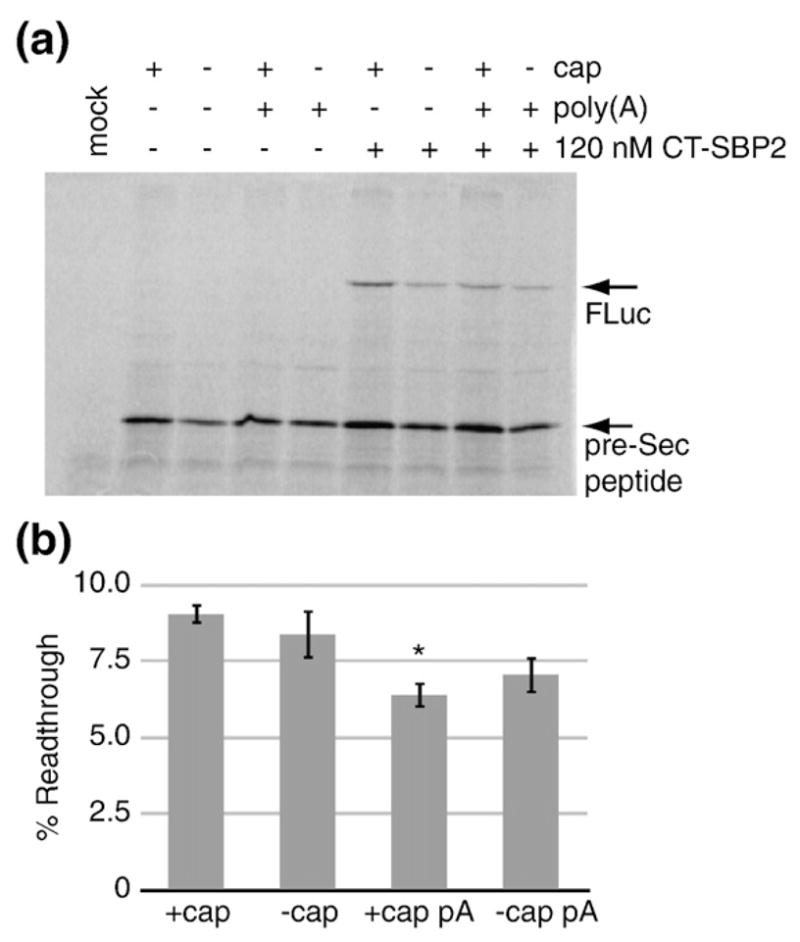

To determine the effect of the m7G cap and poly (A) tail on Sec incorporation efficiency, we utilized a previously described firefly luciferase Sec incorporation reporter (FLuc-Sec/wt) containing a UGA codon at position 258 and the GPX4 SECIS element in the 3′UTR.10 Polyadenylated versions of this construct were generated by subcloning poly(A102) downstream of the SECIS element [Fig. 1; FLuc-Sec/wt/p(A)]. Translation of the FLuc-Sec/wt reporter is known to produce a stable pre-Sec peptide resulting from termination at the Sec codon that serves as an internal control for RNA levels and loading. In addition, full-length luciferase is produced as a result of Sec incorporation.10 Capped or uncapped mRNA containing or lacking a poly(A) tail were in vitro transcribed and then translated in rabbit reticulocyte lysate in the presence or absence of saturating CT-SBP2 (120 nM) and [35S]Met. Figure 2a shows that SBP2-dependent Sec incorporation, as measured by full-length FLuc production, occurred regardless of the cap or poly(A) status of the reporter mRNA. To determine if the 5′ cap or poly(A) tail can influence Sec incorporation efficiency, we normalized band densities to the number of Met residues per peptide and calculated the ratio of full-length luciferase to the sum of pre-Sec peptide and full-length FLuc products expressed as a percentage. Sec incorporation efficiencies for capped and uncapped mRNAs lacking a poly(A) tail were calculated to be 9% and 8.4%, respectively (Fig. 2b). On this occasion, the presence of a poly(A) tail, regardless of cap status, resulted in a small but statistically significant ~30% reduction in Sec incorporation yielding 6.4% efficiency (p =0.009). Subsequent analyses with different batches of reticulocyte lysate show varying levels of this poly(A) effect, which may correlate with batch-specific differential poly(A) stability (data not shown).

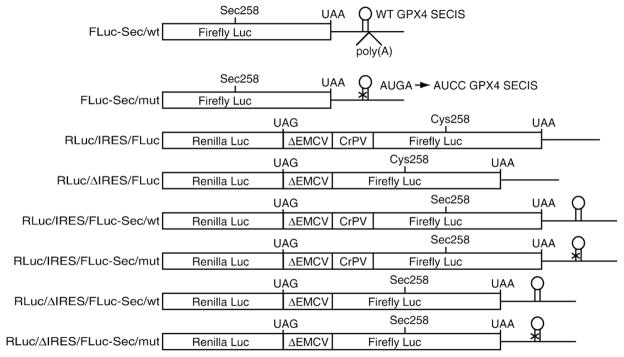

Fig. 1.

Constructs used to test Sec incorporation for the requirement of canonical translation initiation factors. The monocistronic firefly luciferase (FLuc) reporters (FLuc-Sec/wt or mut) have an in-frame UGA codon at position 258 and a wild-type (wt) or mutant (mut) GPx4 SECIS element. The position of the poly(A) tract for poly(A)+ variants is shown for FLuc-Sec/wt, which is annotated as FLuc-Sec/wt/p(A) in the text. All dual luciferase constructs have 5′ Renilla luciferase cistron (RLuc) and a 3′ FLuc cistron. The intercistronic region consists of highly structured RNA (ΔEMCV) and either contain (IRES) or lack (ΔIRES) the CrPV intergenic IRES. The dual luciferase constructs containing or lacking the cricket paralysis virus intergenic IRES (CrPV IRES) were generously provided by Dr. Eric Jan (University of British Columbia) and are described by Wilson et al.18 Variations of the dual luciferase reporters were generated such that FLuc contains a Sec codon at position 258 and a wild-type or mutant GPx4 SECIS element in the 3′ UTR.

Fig. 2.

5′ cap and 3′ poly(A) tail are not required for Sec incorporation. (a) SDS-PAGE gel of [35S]methionine labeled in vitro translated capped and uncapped FLuc-Sec/wt mRNAs with or without a poly(A) tail, as indicated, in the presence or absence of 120 nM recombinant CT-SBP2. The mock reaction lacks both mRNA and CT-SBP2. SDS-PAGE gels were visualized by Phosphor-Imaging and quantitated with ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare). (b) The Sec incorporation efficiencies for reactions containing CT-SBP2 were calculated as percent readthrough=FLuc/(FLuc+pre-Sec peptide)×100 after correction for the number of methionine residues per peptide. The asterisk denotes that the +cap pA value is significantly less than the +cap by Student’s t test (p=0.009). Data are mean±standard error of the mean, n=3.

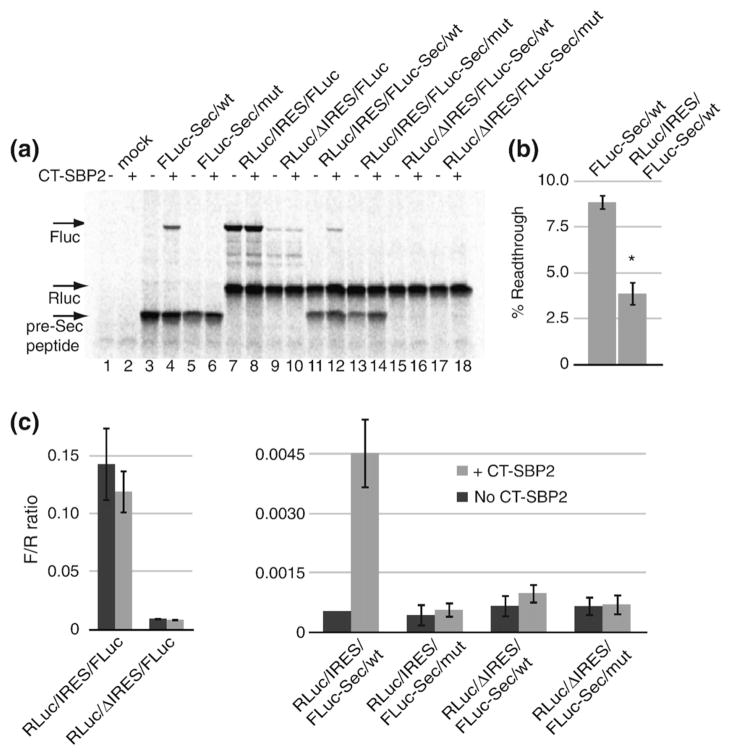

In order to investigate whether or not initiation factors are required for Sec incorporation, we utilized uncapped reporter mRNAs depicted in Fig. 1. Monocistronic control constructs are identical to those used for Fig. 2 (FLuc-Sec/wt or mut). Dicistronic reporter constructs contain a 5′ Renilla luciferase cDNA (RLuc) and a 3′ FLuc cDNA. The intercistronic region contains an inactive EMCV IRES (ΔEMCV) that provides a highly structured RNA to prevent ribosomal scanning to the FLuc cistron after termination at the RLuc cistron.18 The intercistronic region also contains or lacks the CrPV intergenic IRES (IRES and ΔIRES, respectively; see Fig. 1 for construct nomenclature). To test IRES-mediated Sec incorporation, we modified the RLuc/IRES/FLuc and RLuc/ΔIRES/FLuc constructs to contain a Sec (UGA) codon corresponding to amino acid 258 in FLuc and a wild-type or mutant GPX4 SECIS element in the 3′UTR (e.g., RLuc/IRES/FLuc-Sec/wt; Fig. 1). All mutant SECIS elements have the SECIS core motif (AUGA) mutated to AUCC, which prevents Sec incorporation.9

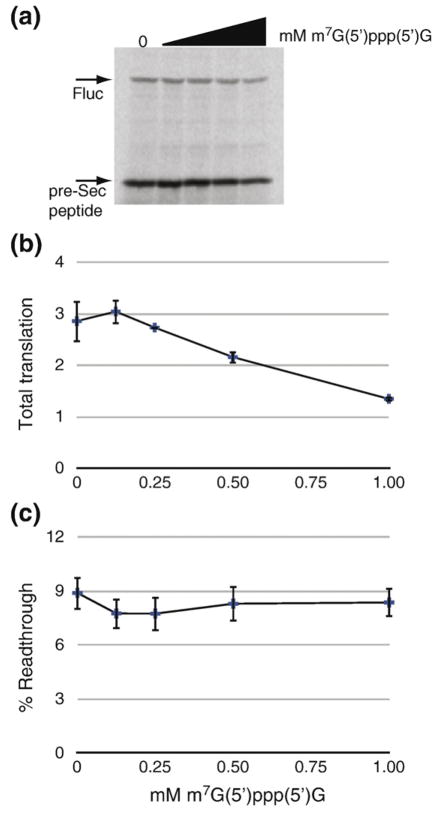

In order to determine if Sec incorporation can occur when translation is driven by the CrPV IRES, we translated each of the uncapped dicistronic reporter mRNAs in rabbit reticulocyte lysate in the presence of [35S]methionine and the presence or absence of 120 nM recombinant CT-SBP2. The eIF-dependent RLuc translation remained constant, indicating that the presence of a Sec codon, SECIS element, and CT-SBP2 had no impact on translation of the first cistron (Fig. 3a, lanes 7–18). The eIF-independent production of wild-type FLuc (no Sec codon) was highly IRES-dependent (compare lanes 7 and 8 to lanes 9 and 10). Likewise, pre-Sec peptide production was also highly IRES-dependent (compare pre-Sec peptide levels in lanes 11–14 to those in lanes 15–18). Importantly, Fig. 3a also shows IRES-driven Sec incorporation since FLuc production is both SBP2-dependent (compare lanes 11 and 12) and SECIS-dependent (compare lanes 12 and 14), demonstrating that Sec incorporation can result from eIF-independent translation. To quantitatively measure the efficiency of IRES-driven Sec incorporation, we performed separate in vitro translation reactions of uncapped FLuc-Sec/wt and RLuc/IRES/FLuc-Sec/wt and measured pre-Sec peptide and FLuc levels directly using PhosphorImager analysis of SDS-PAGE gels and found that the average efficiency of Sec incorporation was 3.8% for RLuc/IRES/FLuc-Sec/wt compared to 8.8% for the Fluc-Sec/wt control (Fig. 3b), with a Student’s t test yielding a p value of 0.006. In addition, the ratio of FLuc to RLuc enzyme activities (F/R) was used to control for mRNA levels and loading as shown in Fig. 3c. Interestingly, the F/R ratio for the RLuc/IRES/FLuc-Sec/wt construct was ~25 times lower than that for the non-Sec-containing RLuc/IRES/FLuc, also indicating an efficiency of only 4%. To determine if the reduced Sec incorporation efficiency observed with IRES-driven translation was a consequence of inefficient translation initiation, we translated capped FLuc-Sec/wt mRNA in the presence of m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G cap analog. Increasing amounts of cap analog to 1 mM resulted in an approximately twofold decrease in total translation (Fig. 4a and b). However, Sec incorporation efficiency was not altered by the presence of cap analog (Fig. 4c). Similar results were obtained when a G(5′)ppp(5′) A cap analog was used (data not shown). These data suggest that the inefficient Sec incorporation as a result of IRES-driven translation is specific for the CrPV IRES and potentially implicates an initiation factor in determining Sec incorporation rates. The lack of an effect on Sec insertion efficiency in the presence of cap analog suggests that such a regulatory event occurs downstream of eIF4F binding to the 5′ cap of the mRNA. One possibility would be regulation of 60S subunit joining to the 43S preinitiation complex to regulate 80s ribosome loading. This model would be consistent with that proposed by Fixsen et al.19 where reduced ribosome loading as a result of programmed UAG read-through resulted in increased Sec incorporation efficiency.

Fig. 3.

Sec incorporation does not require translation initiation factors. (a) Representative SDS-PAGE gel of [35S] methionine labeled in vitro translation reactions of the indicated uncapped mRNAs in the presence or absence of 120 nM CT-SBP2. Translation products are indicated by the arrows. (b) Sec incorporation efficiencies for uncapped FLuc-Sec/wt and RLuc/IRES/FLuc-Sec/wt in the presence of 120 nM CT-SBP2 were calculated as percent readthrough=FLuc/(FLuc+pre-Sec peptide)×100 after correction for the number of methionine residues per peptide. Data are mean ±standard error of the mean, n=3. (c) FLuc/RLuc activity ratios (F/R) for the same reactions as in (a). Dark and light bars represent the absence or presence of 120 nM CT-SBP2, respectively. Data are mean±standard error of the mean, n=3, except for RLuc/IRES/FLuc-Sec/mut where n=2.

Fig. 4.

Inefficient translation initiation does not reduce Sec incorporation. (a) Representative SDS-PAGE gel of [35S]methionine labeled in vitro translation reactions of capped FLuc-Sec/wt mRNA in the presence of 120 nM CT-SBP2 and 0–1 mM m7G(5′)ppp(5′)G cap analog. Reactions supplemented with cap analog contained 0.8 mol MgCl2 per mole of cap. (b) Quantitation of total translation in the presence of cap analog as measured by band densitometry (arbitrary units). (c) Quantitation of Sec incorporation efficiency, as described for previous figures, in the presence of cap analog. Data are mean± standard error of the mean, n=3.

In vivo regulation of Sec incorporation at the level of translation initiation could have several advantages. Several selenoproteins, notably the glutathione peroxidases, are key proteins in mitigating intracellular oxidative stress.20 Under high stress conditions where Sec incorporation in these proteins would be preferential to that in other selenoproteins, a selective step at initiation could conserve energy. Further evidence for regulation of selenoprotein translation at the level of initiation comes from Ufer et al.21 who recently reported that Grsf1 upregulates GPX4 expression by binding to the GPX4 5′UTR and increasing loading onto polysomes. However, it is not known whether Grsf1 increases GPX4 expression by increasing Sec incorporation efficiency or by increasing total translation of GPX4 by increased ribosome loading, or both. Selenoprotein P (SelP) presents another case where regulating Sec incorporation at the level of translation initiation is an attractive model. Human SelP differs from other selenoproteins in that its open reading frame contains 10 Sec codons and its 3′UTR has 2 SECIS elements.22 SelP is the major carrier of selenium in plasma and distributes selenium throughout the body.23 Given the inefficient nature of Sec incorporation in vitro, it is likely that SelP translation involves as yet unidentified factors, possibly involved at initiation, in order to achieve efficient and processive Sec incorporation (i.e., successful incorporation of more than one Sec residue per open reading frame). While the preceding hypothesis still warrants investigation, Fixsen and Howard recently reported that in the context of more than one UGA codon in a dual luciferase reporter, the first UGA codon is recoded inefficiently (7%) while all downstream UGA codons exhibit ~70% Sec incorporation efficiency, thus suggesting additional mechanisms for determining Sec incorporation efficiency.19 Future studies will be aimed at identifying the step in translation initiation that is regulated during Sec incorporation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kelvin Caban and Jonathan Gonzales-Flores for insightful discussions. This work was supported by Public Health Service grant GM077073 (P.R.C.).

Abbreviations used

- Sec

selenocysteine

- SECIS

selenocysteine insertion sequence

- UTR

untranslated region

- SBP2

SECIS binding protein 2

- IRES

internal ribosome entry site

- SelP

selenoprotein P

References

- 1.Berry MJ, Banu L, Harney JW, Larsen PR. Functional characterization of the eukaryotic SECIS elements which direct selenocysteine insertion at UGA codons. EMBO J. 1993;12:3315–3322. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allmang C, Krol A. Selenoprotein synthesis: UGA does not end the story. Biochimie. 2006;88:1561–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caban K, Copeland PR. Size matters: a view of selenocysteine incorporation from the ribosome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:73–81. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5402-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fletcher JE, Copeland PR, Driscoll DM, Krol A. The selenocysteine incorporation machinery: interactions between the SECIS RNA and the SECIS-binding protein SBP2. RNA. 2001;7:1442–1453. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donovan J, Caban K, Ranaweera R, Gonzales-Flores JN, Copeland PR. A novel protein domain induces high affinity selenocysteine insertion sequence binding and elongation factor recruitment. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35129–35139. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806008200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caban K, Kinzy SA, Copeland PR. The L7Ae RNA binding motif is a multifunctional domain required for the ribosome-dependent Sec incorporation activity of Sec insertion sequence binding protein 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:6350–6360. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00632-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berry MJ, Harney JW, Ohama T, Hatfield DL. Selenocysteine insertion or termination: factors affecting UGA codon fate and complementary anticodon:codon mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3753–3759. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.18.3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grundner-Culemann E, Martin GW, Tujebajeva R, Harney JW, Berry MJ. Interplay between termination and translation machinery in eukaryotic selenoprotein synthesis. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:699–707. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta M, Copeland PR. Functional analysis of the interplay between translation termination, selenocysteine codon context, and selenocysteine insertion sequence-binding protein 2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36797–36807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707061200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehta A, Rebsch CM, Kinzy SA, Fletcher JE, Copeland PR. Efficiency of mammalian selenocysteine incorporation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:37852–37859. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404639200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nasim MT, Jaenecke S, Belduz A, Kollmus H, Flohé L, McCarthy JE. Eukaryotic selenocysteine incorporation follows a nonprocessive mechanism that competes with translational termination. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:14846–14852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.14846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Copeland PR. Regulation of gene expression by stop codon recoding: selenocysteine. Gene. 2003;312:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(03)00588-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonenberg N, Dever TE. Eukaryotic translation initiation factors and regulators. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2003;13:56–63. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(03)00009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fletcher JE, Copeland PR, Driscoll DM. Polysome distribution of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase mRNA: evidence for a block in elongation at the UGA/selenocysteine codon. RNA. 2000;6:1573–1584. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sonenberg N, Hinnebusch AG. Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell. 2009;136:731–745. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jan E, Sarnow P. Factorless ribosome assembly on the internal ribosome entry site of cricket paralysis virus. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:889–902. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilson JE, Pestova TV, Hellen CU, Sarnow P. Initiation of protein synthesis from the A site of the ribosome. Cell. 2000;102:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson JE, Powell MJ, Hoover SE, Sarnow P. Naturally occurring dicistronic cricket paralysis virus RNA is regulated by two internal ribosome entry sites. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4990–4999. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.4990-4999.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fixsen SM, Howard MT. Processive selenocysteine incorporation during synthesis of eukaryotic selenoproteins. J Mol Biol. 2010 Apr 24; doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.033. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu J, Holmgren A. Selenoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:723–727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800045200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ufer C, Wang CC, Fähling M, Schiebel H, Thiele BJ, Billett EE, et al. Translational regulation of glutathione peroxidase 4 expression through guanine-rich sequence-binding factor 1 is essential for embryonic brain development. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1838–1850. doi: 10.1101/gad.466308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill KE, Lloyd RS, Burk RF. Conserved nucleotide sequences in the open reading frame and 3′ untranslated region of selenoprotein P mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:537–541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burk RF, Hill KE. Selenoprotein P: an extracellular protein with unique physical characteristics and a role in selenium homeostasis. Annu Rev Nutr. 2005;25:215–235. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.24.012003.132120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]