Abstract

Due to non-specific symptoms following acute respiratory viral infections, it is difficult for many countries without on-going transmission of a novel coronavirus to rule out other possibilities including influenza in advance of isolating imported febrile individuals with a possible exposure history. The incubation period helps differential diagnosis and up to two days is suggestive of influenza. It is worth accounting for the incubation period as part of the case definition of novel coronavirus infection.

Introduction

Two cases of severe respiratory infection have been confirmed as caused by a novel coronavirus [1]. The case definitions have been issued by the World Health Organization (WHO), mainly based on acute respiratory illness, pneumonia (or suspicion of pulmonary parenchymal disease) and travel history [2]. To describe the clinical characteristics of the novel coronavirus infection, the incubation period has played a key role in suspecting Saudi Arabia and Qatar as geographic locations of exposure for the abovementioned two cases [1,3] and comparing the possible length of the incubation period against known incubation periods of human coronaviruses including that of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) [3,4]. The present study intends to supplement that the incubation period can be treated as more useful information for all countries without on-going transmission across the world to distinguish the coronavirus infection from other viral respiratory infections, most notably influenza.

Methods

Motivating case study

In Hong Kong, a 4 year-old boy from Saudi Arabia was admitted to a hospital equipped with an isolation ward on 7 October 2012, suspected of novel coronavirus infection. He had a fever, cough and vomiting, but did not have pneumonia. His father had a fever two days in advance of the illness onset of the boy, but has recovered before they arrived in Hong Kong on the date of admission [5]. In other words, assuming that the father was the source of infection, the serial interval was 2 days, which is typically longer than the incubation period [6,7], and thus, the incubation period was likely 2 days or shorter. On the following day of admission, the boy tested negative for the coronavirus, but tested positive for influenza A (H1N1-2009) [5]. A similar event, but with two severe pneumonia cases, occurred in Denmark where a cluster of febrile cases, with a travel history to the above mentioned countries among a part of cases, led to a suspicion of the novel coronavirus infection. However, later laboratory testing revealed that the respiratory illnesses were caused by infection with an influenza B virus. We believe that the distinction between coronavirus and influenza virus infections in these settings could have been partially made by considering the length of the incubation period.

Bayesian model

Let fi(t|θi) be the probability density function of the incubation period t of virus i governed by parameter θi. The incubation period distributions for a variety of acute upper respiratory viral infections have been fitted to lognormal distributions elsewhere [4,8] and are assumed known hereafter. The median incubation periods of SARS, non-SARS human coronavirus infection, and influenza A and influenza B virus infections have been estimated at 4.0, 3.2, 1.4 and 0.6 days, respectively [4]. It should be noted that the median incubation periods of influenza have been estimated as shorter than those of coronaviruses. The incubation period, fi is assumed to be independent across different viruses i. Due to shortage of information, we ignore the time-dependence and geographic heterogeneity in the risk of infection for all viruses. The posterior probability of novel coronavirus infection (which is labelled as i=1) given an incubation period t, Pr(novel coronavirus|t), is then obtained by using a Bayesian approach:

| (1) |

where qi denotes the prior probability of virus i (e.g. q1=Pr(novel coronavirus); the probability that the novel coronavirus is responsible for acute respiratory viral infection with unknown aetiology among all of such infections) which can be equated to the relative frequency of virus i infection during viral aetiological study (e.g. using the relative incidence by aetiological agent) [9,10]. Since the observed data are recorded at daily basis, the incubation period in (1) is discretized as,

| (2) |

for t>0.

Since the prior probability qi is unknown for imported cases with acute respiratory illness, two conservative approaches, which would not lead to an underestimation of the probability of novel coronavirus infection, should be taken. Such approaches include (i) allocating an equal probability as the prior probability for all possible viruses (e.g. for a differential diagnosis of two viral diseases, we allocate 0.5 for each) or (ii) using published viral aetiological study result among those with an acute respiratory disease (e.g. using virus detection results among influenza-like illness (ILI) patients). As an example for the latter approach, the observed numbers of coronavirus infections and influenza A and B virus infections among a total of 177 child ILI cases with known viral aetiology have been 12, 40 and 5 cases, respectively, in Madagascar [11]. Here we focus on this particular dataset among children only, because a case of our interest in Hong Kong, which is used for the exposition of our theoretical idea, was 4 year old. Moreover, we used the data from Madagascar, because this study appeared as informative in closely investigating the frequency of different types of human coronaviruses among child ILI cases [11]. It should be noted that n=12 in Madagascar does not represent the frequency of novel coronavirus, but that caused by other human coronaviruses, while the estimation of the posterior probability of novel coronavirus infection using equation (1) requires the prior probability of the novel coronavirus. We use this figure for the novel coronavirus, only for now, for the exposition of our theory.

Results

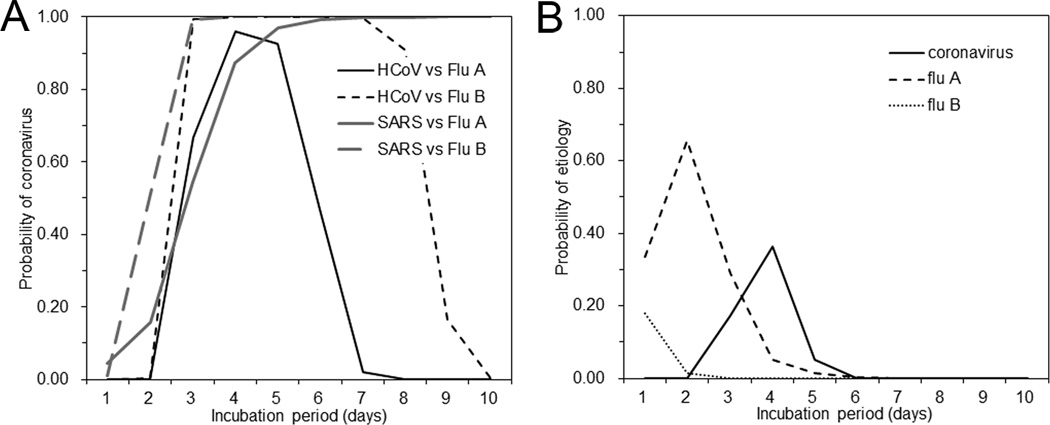

Figure 1A shows the conditional probability of coronavirus infection given the incubation period (based on equation (1)), in a setting where one has to differentiate coronavirus infection from influenza virus infection, assuming an equal probability 0.5 for each of the viruses. Assuming that the observed incubation period of the above mentioned child case in Hong Kong is 2 days, the probability of non-SARS human coronavirus infection is smaller than 0.1%. When using the incubation period of SARS as reference to represent the incubation period of novel coronavirus, the probability of the coronavirus infection with 2-day incubation period is 15.7%. In other words, the probability of influenza A given 2-day incubation period is as high as 99.9% and 84.3% when comparing between influenza A and either non-SARS or SARS coronaviruses, respectively, and various actions in the field including case isolation, contact tracing and laboratory testing can account for this probability (e.g. contact tracing may assume that new generations of cases would arise every 3 days on average as being consistent with influenza transmission). Influenza B virus also yielded qualitatively similar results (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Probability of coronavirus infection given the incubation period of a case.

The observed length of the incubation period of a case can partially help differential diagnosis. A. The probability of coronavirus infection given the incubation period, when comparing between coronavirus infection and influenza virus infection as possible diagnoses. We use 50% for each of the two viruses (i.e. coronavirus vs influenza virus) for a conservative argument to avoid an underestimation of the risk of novel coronavirus. Since known coronaviruses are classified into severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated virus and non-SARS, and because influenza viruses are crudely classified as type A and B viruses, there are four possible combinations for comparison. HCoV stands for human coronaviruses other than severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), while Flu A and Flu B stand for influenza A and B viruses, respectively. B. The probability of coronavirus infection given the incubation period, using empirically observed viral aetiology data as a prior information among influenza-like illness cases in Madagascar [11] with a total of n=177 samples for those aged below 5 years. The observed number of isolates, i.e., Flu A (n=40), Flu B (n=5), human coronaviruses (n=12) and others (n=120), were used to calculate qi in equation (1). n=12 for ordinary human coronaviruses is used as if it gave the frequency of a novel coronavirus, only for now, for the exposition of our theoretical idea. The incubation periods of viruses other than influenza viruses and human coronaviruses were assumed to be uniformly distributed from Day 1 to Day 10, for a conservative argument to avoid an underestimation of the probability of novel coronavirus.

It should be noted that the actual relative frequency of novel coronavirus is much smaller than that discussed here due to the absence of substantial human-to-human transmission events [3], while influenza A virus has already circulated in human population. Thus, the posterior probability of novel coronavirus in reality would be much smaller than that illustrated in Figure 1.

When we use the empirically observed frequency of human coronaviruses based on viral aetiological study data among child ILI cases (Figure 1B), the probabilities of coronavirus and influenza A and B virus are estimated at <0.1%, 65.7% and 1.4%, respectively. It is remarkable that ILI with the incubation period of 2 days is most likely caused by influenza A virus. However, novel coronavirus may be suspected if the incubation period is in the order of 3–5 days.

Discussion

As demonstrated in the present study, the probability of infection with novel coronavirus can be inferred from the incubation period of each single case with suspicion, which we believe is useful for deciding an alert level of public health and strictness of movement restriction and contact tracing among imported cases of acute respiratory viral infection, especially with mild and non-specific symptoms. We have shown that the incubation period of 2 days or shorter is strongly suggestive of influenza, while the incubation period from 3–5 days could potentially be consistent with the incubation period of human coronaviruses. Of course, the implementation of isolation measure, contact tracing and other interventions would also depend on other factors including the perceived importance and cost of the interventions, but we have shown at least that the incubation period would yield supplementary information for differential diagnosis and decision making. We believe that it is worth considering incorporating the incubation period into the case definition as soon as the incubation period data are additionally collected.

In practice, the proposed approach fits case investigations (or outbreak investigations) in which precise information of contacts is collected, because having an estimate of the incubation period is frequently the case. However, three common technical issues should be discussed. First, as an infection event is not directly observable, multiple contacts can always limit information on an incubation period in a straightforward way. For instance, we cannot technically rule out the possibility that the child case in Hong Kong was exposed to someone other than the father in advance of their travel to Hong Kong. Second, the incubation period tends to be crude, especially for the first few cases, e.g., when the length of travel with an exposure is long for imported cases. Third, one cannot guarantee that the incubation period of a novel pathogen always falls nearby that caused by closely-related pathogens. For instance, the incubation period of Escherichia coli O104:H4 infection has revealed a longer incubation period than that of E. coli O157:H7 [12]. To address the second and third points, it is essential to collect multiple datasets of the incubation period with a brief exposure.

In addition to the improvement in differential diagnosis, there are important public health implications. First, given that the incubation period distribution helps differential diagnosis, especially when clinical signs and symptoms are non-specific, the distribution should be estimated early during the course of an epidemic of any novel infectious disease. For this reason, detailed travel history of imported cases should be explored, as it can inform the incubation period distribution [8,13]. Moreover, outbreak reports, including case reports, should explicitly and routinely document the detailed history of exposure (e.g. the length and timing of exposure along with the illness onset date) among all cases. Second, the overall risk estimate (e.g. the relative incidence) would be deemed essential to validate the proposed Bayesian model (1), although in reality the prior probability considerably varies with time and place. To understand the on-going risk of infection with a novel virus explicitly, a population wide serological survey, which helps inferring at least the cumulative incidence, would be a useful method to offer insights into the aetiology. Finally, while estimating the relative probability of alternative aetiologies can help with diagnosis, decisions on possible control measures (such as isolation of cases) could also be affected by other concerns including reduction in the risk of larger outbreaks.

Acknowledgment

The work of HN was supported by the JST PRESTO program and St Luke’s Life Science Institute Research Grant for Clinical Epidemiology Research 2012. KE received scholarship support from the Japan Society for Promotion of Science (JSPS). This work also received financial support from the Harvard Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant no. U54 GM088558).

References

- 1.Danielsson N, Catchpole M On Behalf Of The Ecdc Internal Response Team C. Novel coronavirus associated with severe respiratory disease: Case definition and public health measures. Euro Surveill. 2012;17(39) doi: 10.2807/ese.17.39.20282-en. pii=20282. Available from: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global alert and response (GAR): revised interim case definition—novel coronavirus. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Accessed October 11, 2012]. Available at http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/case_definition/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pebody RG, Chand MA, Thomas HL, Green HK, Boddington NL, Carvalho C, et al. The United Kingdom public health response to an imported laboratory confirmed case of a novel coronavirus in September 2012. Euro Surveill. 2012;17(40) pii=20292. Available from: http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ViewArticle.aspx?ArticleId=20292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lessler J, Reich NG, Brookmeyer R, Perl TM, Nelson KE, Cummings DA. Incubation periods of acute respiratory viral infections: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:291–300. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70069-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.South China Morning Post. Saudi boy in Hong Kong has flu, not Sars-like virus. 2012 Oct 8; [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nishiura H, Eichner M. Infectiousness of smallpox relative to disease age: estimates based on transmission network and incubation period. Epidemiol. Infect. 2007;135(7):1145–1150. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806007618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klinkenberg D, Nishiura H. The correlation between infectivity and incubation period of measles, estimated from households with two cases. J Theor. Biol. 2011;284(1):52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishiura H, Inaba H. Estimation of the incubation period of influenza A (H1N1-2009) among imported cases: addressing censoring using outbreak data at the origin of importation. J Theor. Biol. 2011;272(1):123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishiura H. Incubation period as a clinical predictor of botulism: analysis of previous izushi-borne outbreaks in Hokkaido, Japan, from 1951 to 1965. Epidemiol. Infect. 2007;135(1):126–130. doi: 10.1017/S0950268806006169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lessler J, Brookmeyer R, Perl TM. An evaluation of classification rules based on date of symptom onset to identify health-care-associated infections. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(10):1220–1229. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Razanajatovo NH, Richard V, Hoffmann J, Reynes JM, Razafitrimo GM, Randremanana RV, Heraud JM. Viral etiology of influenza-like illnesses in Antananarivo, Madagascar, July 2008 to June 2009. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17579. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchholz U, Bernard H, Werber D, Böhmer MM, Remschmidt C, Wilking H, Deleré Y, an der Heiden M, Adlhoch C, Dreesman J, Ehlers J, Ethelberg S, Faber M, Frank C, Fricke G, Greiner M, Höhle M, Ivarsson S, Jark U, Kirchner M, Koch J, Krause G, Luber P, Rosner B, Stark K, Kühne M. German outbreak of Escherichia coli O104:H4 associated with sprouts. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(19):1763–1770. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishiura H, Lee HW, Cho SH, Lee WG, In TS, Moon SU, et al. Estimates of short- and long-term incubation periods of Plasmodium vivax malaria in the Republic of Korea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101(4):338–343. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]