Abstract

The head is thought to be rational and cold, whereas the heart is thought to be emotional and warm. Eight studies (total N = 725) pursued the idea that such body metaphors are widely consequential. Study 1 introduced a novel individual difference variable, one asking people to locate the self in the head or the heart. Irrespective of sex differences, head-locators characterized themselves as rational, logical, and interpersonally cold, whereas heart-locators characterized themselves as emotional, feminine, and interpersonally warm (Studies 1–3). Study 4 found that head-locators were more accurate in answering general knowledge questions and had higher GPAs and Study 5 found that heart-locators were more likely to favor emotional over rational considerations in moral decision-making. Study 6 linked self-locations to reactivity phenomena in daily life –e.g., heart-locators experienced greater negative emotion on high stressor days. Study 7 manipulated attention to the head versus the heart and found that head-pointing facilitated intellectual performance, whereas heart-pointing led to emotional decision-making. Study 8 replicated Study 3’s findings with a nearly year-long delay between the self-location and outcome measures. The findings converge on the importance of head-heart metaphors for understanding individual differences in cognition, emotion, and performance.

Keywords: Personality, Individual Differences, Metaphor, Cognition, Emotion, Performance

Lakoff and Johnson (1999) suggested that conceptual metaphors guide thought, emotion, and behavior in a hitherto unappreciated manner. Since then, significant progress has been made in documenting the importance of conceptual metaphors in the social psychology literature (Landau, Meier, & Keefer, 2010). For example, positive evaluations are faster when perceptual manipulations are consistent with prominent metaphors (e.g., “good is up”: Meier & Robinson, 2004a). Social judgments, too, are influenced by metaphor-consistent manipulations. For example, manipulations of physical warmth lead to “warmer” interpersonal judgments (Williams & Bargh, 2008a) and moral judgments are more severe when individuals are placed in dirty rooms, consistent with “dirt” metaphors for moral depravity (Schnall, Haidt, Clore, & Jordan, 2008).

Metaphor representation theory (Lakoff & Johnson, 1999) might have profound implications for personality psychology, but there is surprisingly little research of this type (Robinson & Fetterman, in press). There are at least two potential reasons for this largely missing interface. First, conceptual metaphors (e.g., “good is up”, “friendly is warm”, “immoral is dirty”) are consensually shared by members of a culture (Lakoff, 1986), are largely universal across cultures (Kövecses, 2000), and therefore may constrain thinking and behavior in a similar manner across individuals (Landau et al., 2010). Second, manipulations (e.g., of dirt, warmth, or higher vertical position) are potentially irrelevant in understanding individual differences, which are not commensurate with manipulation effects (Kenrick & Funder, 1988). Considerable creativity, therefore, is necessary for translating the metaphor representation theory to the individual differences realm (Robinson & Fetterman, in press).

Despite these obstacles, we believe that metaphor representation theory may have profound implications for personality psychology. If people think and behave in metaphoric terms (Lakoff & Johnson, 1999; Landau et al., 2010), then such processes should be as relevant in understanding individual differences as in understanding manipulation effects. We introduce a novel assessment device and, in doing so, capitalize on the fact that people ascribe very different metaphoric functions to the head versus the heart.

Head versus Heart Metaphors

The self is not just a psychological entity, but also a multi-faceted body structure – it has hands, feet, genitals, a head, etc. Two body parts – the head and the heart – have been ascribed particular psychological significance throughout the history of Western civilization. Plato (trans. 1987) was among the first to suggest that the head is the source of rational wisdom, whereas the heart is the source of the passions. Philosophers and writers subsequent to Plato have elaborated on the purported significance of the head versus the heart in understanding rational thinking, emotional responding, and decision making, but in a way that preserves Plato’s presumed functions for these two body organs. Similar heart and head metaphors pervade the work of Shakespeare, for example, but also many other writers (Swan, 2009).

In our daily lives, too, we frequently make references to the head or the heart. To “use one’s head” means to think rationally and logically about a problem, whereas to “lose one’s head” means to lose the capacity for clear thinking. The organ located in the head –the brain – is also used to characterize intelligence (e.g., “he has a brain”, “she is brainy”). On the other hand, to be “stuck in one’s head” suggests a lack of social connection and we certainly stereotype brainy individuals as more interested in intellectual problems than in other people. Common metaphors for the head, then, suggest greater rationality and intelligence, albeit in combination with some lack of social connection.

Metaphors for the heart appear to be two-fold. As indicated above, the head and the heart are frequently contrasted with each other in their purported functions (Swan, 2009). Further, heart metaphors are common in characterizing greater levels of emotionality (Kövecses, 2000). To “follow one’s heart” means to let emotions dictate one’s life choices. A person has “heartache” to the extent that he or she ruminates and dwells upon adverse personal events. On the other hand, a different class of metaphors links the heart to greater social connection and caring. A person “has a heart” to the extent that he/she cares about others. Such caring individuals are also characterized as “having a big heart” or “having a warm heart”. In sum, metaphors for the heart suggest both its role in emotionality in general and caring in particular.

A Novel Individual Difference Measure and Hypotheses

Most common metaphors (including those for the head and the heart) are likely to be strongly shared within a culture (Lakoff, 1986) and cross-culturally shared as well (Kövecses, 2000). From one perspective, such consensual associations render it uncertain whether conceptual metaphors may be explanatory in the personality realm (Landau et al., 2010; Robinson & Fetterman, in press). From another perspective, though, the consensual nature of conceptual metaphors can be capitalized on. Of importance to the current investigation, if the head is rational and the heart is emotional (Swan, 2009), then forcing individuals to choose whether the head or the heart is the predominant locus of the self may be of great value in predicting numerous outcomes consistent with head versus heart metaphors.

Accordingly, we developed a novel individual difference measure. Respondents were forced to pick the head (brain) or the heart as the better location of their own self. In this context, the self is the abstract concept (i.e., the “target”) and a body organ is the concrete entity (i.e., the “source”) used to think about the self. If the self-location measure functions as other metaphoric effects that have been demonstrated (Landau et al., 2010), then we might expect head- and heart-locators to possess some of the characteristics that we metaphorically associate with these body organs. In Study 1, we hypothesized that heart-locators – relative to head-locators - would report greater emotionality. In Study 2, we hypothesized that head-locators would favor rational thinking styles, whereas heart-locators would favor experiential thinking. In Study 3, we hypothesized that head-locators would report greater levels of interpersonal coldness, whereas heart-locators would report greater levels of interpersonal warmth. In Study 4, we hypothesized that head-locators would have higher GPAs. In Study 5, we hypothesized that heart-locators, relative to head-locators, would solve moral dilemmas in an emotional manner. In Study 6, we hypothesized that heart-locators would exhibit greater negative emotional reactivity to daily stressors. In these studies, a number of additional hypotheses were made as well and we save them for the relevant introduction, results, and discussion sections. In general terms, though, we expected head-locators to be rational, intelligent, and interpersonally cold, whereas we expected heart-locators to be emotional, attentive to their emotions, and interpersonally warm.

In Study 7, we manipulated attention to the head versus the heart by asking individuals to point to the head versus the heart. Head-pointers were hypothesized to answer general knowledge questions more accurately, whereas heart-pointers were hypothesized to solve moral dilemmas in a more emotional manner. Although our general focus was on individual differences in self-location, this study is an important one from a causal-experimental perspective. Study 8, finally, returns to individual difference predictions, but in the context of a long time delay between self-location assessments and outcome measures. Study 8, relative to Studies 1–6, can therefore better support the dispositional nature of self-locations and their predictive importance.

Study 1

Study 1 introduces the self-location measure. The head and the heart are both viewed as sources of wisdom in common metaphors. For this reason, we expected a relatively even split of heart-locating and head-locating individuals. Women are both viewed and view themselves as more emotional in nature (Robinson & Clore, 2002). For this reason, and because the heart is the purported organ of emotionality, we hypothesized that women, relative to men, would be more likely to think of the self as located in the heart.

Irrespective of sex differences, heart-locating individuals were hypothesized to have higher levels of affect intensity, defined in terms of greater levels of emotionality quite generally (Larsen, Diener, & Emmons, 1986). To “have a heart” suggests greater levels of caring and empathy. Accordingly, we hypothesized that heart-locators would score higher in psychological femininity, which is primarily defined in such terms (Bem, 1974). On the basis of similar considerations, we hypothesized that heart-locators would report liking intimacy-related activities to a greater extent as such activities, too, are marked by and facilitate caring relations with others (McAdams, Diamond, de St. Aubin, & Mansfield, 1997).

Method

Participants and General Procedures

Participants were 112 (47 female) undergraduates from North Dakota State University (NDSU) seeking course credit. Laboratory sessions included groups of 6 or less and all measures were completed on personal computers using MediaLab software. Participants in Study 1, as in Studies 2–5, were told that they would be completing a number of different tasks, some related to perceptions and others related to different aspects of personality.

The Self-Location Measure

Participants were asked the following question: “Irrespective of what you know about biology, which body part do you more closely associate with your self (choose one)?” The irrespective lead-in was useful in focusing individuals on intuitive ideas about the self. Participants were to choose the “Heart” or the “Brain”, which were presented as vertically aligned buttons toward the top of the computer screen. The measure contrasted the heart and the brain because both are internal body organs and therefore commensurate for this reason. For the sake of consistency with prominent metaphors (Swan, 2009), though, we refer to heart-locators versus head-locators in characterizing the results. Choices were made by moving a mouse cursor –placed at center screen –toward the relevant button and then making a left-mouse click. To render the self-location measure strictly comparable across people, and therefore facilitate individual difference comparisons, it was deemed best that the item be exactly the same for everyone. This was accomplished by always placing the heart-related option immediately above the head-related option.

The self must have a head and it must have a heart. Yet, the self-location question is surprisingly easy to answer. For example, when we ask this question in presentations, people have no difficulty answering the question. Moreover, they find their answers to the question so intuitive that they cannot imagine themselves answering the question in any other way than they did. This is likely due to three factors. The conceptual self is identified with the body (Robinson, Mitchell, Kirkeby, & Meier, 2006). Yet, it is not identified with all areas of the body equally (Burris & Rempel, 2004) and the head and the heart are spatially quite distinct, thereby rendering it quite likely that there is more of the (metaphorical) self’s essence in one body part relative to the other. Of most importance, however, there are very prominent metaphors for the head and the heart that are, in some cases, diametrically opposed to each other (Lakoff & Johnson, 1999; Swan, 2009). Participants, then, presumably answer the question by drawing from the intuitive notion that the self is located somewhere in the body (Burris & Rempel, 2004) and the part of the body in which the self is more likely located is consistent with prominent metaphors for the head versus the heart (Swan, 2009).

Outcome Measures

Heart-locators were hypothesized to be higher in affective intensity. A shortened version of the Affect Intensity Measure (AIM: Larsen et al., 1986) was administered to examine this prediction. Participants were asked to rate how characteristic (1 = extremely uncharacteristic; 5 = extremely characteristic) 10 statements from the AIM (e.g., “My emotions tend to be more intense than those of most people”) generally characterize the self. The shortened scale was reliable (M = 3.09; SD = .62; Cronbach’s Alpha = .76).1

Heart-locators were also hypothesized to be higher in psychological femininity. A shortened version of Bem’s (1974) femininity scale was administered. Participants were asked to rate how true (1 = never or almost never true; 7 = always or almost always true) 10 descriptors of femininity (e.g., “affectionate”) were of their personalities. Items were chosen such that they focused on interpersonal warmth and caring in particular terms. The shortened version of the femininity scale was reliable (M = 4.82; SD = .89; Alpha = .86).2

Heart-locators were hypothesized to like intimacy-related activities to a greater extent. We could not locate a self-report scale that was as focused as desired and so we created our own. Each of the 13 items started with the phrase “I like” followed by an activity posited to be intimacy-related in nature (e.g., “helping people”, “sharing my feelings”). Participants indicated their level of agreement with each item in relation to a six-point scale (1 = disagree; 6 = agree). The measure was reliable (M = 4.47; SD = .77; Alpha = .84).3

Results

We viewed it plausible that individuals would differ quite dramatically in whether they viewed the self as a heart- or head-related entity. In fact, 52% of the participants in Study 1 viewed the self as a heart-related entity and 48% viewed the self as a head-related entity. There was thus an even split among responders. On the other hand, women (relative to men) should be more likely to view themselves as heart-related beings. This hypothesis was supported in a chi-square analysis, χ2 = 4.75, p < .05, in that the percentage of women choosing the heart organ was 64%, whereas the percentage of men choosing the heart organ was 43%.

Prominent metaphors suggest that the heart, relative to the head, is the seat of emotionality. Accordingly, we expected heart-locators to score higher in affect intensity. This hypothesis was supported in a one-way ANOVA, which revealed that heart-locators scored higher in affect intensity (M = 3.31) than head-locators (M = 2.85) did, F (1, 110) = 16.98, p < .01, partial eta square = .13. On the other hand, there was a sex difference in self-location, as indicated above. Accordingly, for this outcome measure– and others below –we performed a multiple regression in which self-location (−1 = head; +1 = heart) and participant sex (−1 = male; +1 = female) predictors were simultaneously regressed. Both Self-Location, b = .29, t = 3.44, p < .01, and Participant Sex, b = .39, t = 4.63, p < .01, predicted affect intensity with their overlapping variance statistically controlled.4

Prominent metaphors suggest that the heart, relative to the head, is associated with caring and empathy. Because these qualities are characteristic of psychological femininity, we expected heart-locators to score higher in femininity. This proved to be the case in a one-way ANOVA, as femininity scores were higher among heart-locators (M = 5.23) than head-locators (M = 4.38), F (1, 110) = 33.23, p < .01, partial eta square = .23. In a multiple regression, both Self-Location, b = .39, t = 5.27, p < .01, and Participant Sex, b = .47, t = 6.35, p < .01, predicted psychological femininity with their common variance statistically controlled.

Metaphorically, people who “have hearts” are intimate in their interpersonal functioning. Accordingly, we hypothesized that heart-locators would like engaging in intimacy-related activities (e.g., “sharing my feelings”) to a greater extent. In fact, heart-locators (M = 4.81) did report liking these activities to a greater extent than head-locators (M = 4.11), F (1, 110) = 28.79, p < .01, partial eta square = .21. In a multiple regression controlling for overlapping variance, both the Self-Location variable, b = .36, t = 4.84, p < .01, and Participant Sex, b = .49, t = 6.67, p < .01, predicted greater liking for intimacy-related activities. Correlations among the Study 1 measures are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlations among the Study 1 Measures

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-Location | |||

| 2. Affect Intensity | .37** | ||

| 3. Femininity | .48** | .48** | |

| 4. Liking Intimacy | .45** | .60** | .75** |

= p < .01;

= p < .05;

= p < .10

Discussion and Study 2

All of the hypotheses of Study 1 were supported. We found a relatively even split of heart-locators and head-locators. Further, though, we found that women, relative to men, were more likely to locate the self in the heart, results consistent with women’s greater valuing of their emotions (e.g., Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey, & Palfai, 1995). We note that very similar results occurred in Studies 2–6 and in Study 8; for this reason, we omit similar material in the other interim discussion sections.

Of perhaps more importance, we found that heart-locators had higher levels of affect intensity, results consistent with the heart’s purported role in emotional reactivity (Lakoff & Johnson, 1999). We found that heart-locators had higher levels of psychological femininity, results consistent with the heart’s metaphoric role in caring for others (Swan, 2009). We found that heart-locators liked intimacy-related activities to a greater extent, results consistent with the idea that intimacy draws from the heart’s functions (e.g., “talking from the heart”: Kövecses, 2000). The self-location variable predicted the outcome measures independently of participant sex and the results cannot therefore be ascribed to participant sex. Our self-location variable is nonetheless an entirely novel one to the personality literature and we therefore examined its predictive validity in multiple additional studies.

Study 2 focused on new outcome measures not examined in Study 1. People “following their hearts” presumably do so because they value their emotions to a greater extent (Kövecses, 2000). If so, we should expect a systematic relationship between the self-location variable and valuing the self’s emotions. The attention to emotion scale of Salovey et al. (1995) seeks to assess just such individual differences. Accordingly, we hypothesized that heart-locators would score higher in attention to emotion.

Metaphors for the heart/head distinction primarily reference different thinking styles (Lakoff & Johnson, 1999). Specifically, a heart-based thinking style is intuitive (“follow your heart”), whereas a head-based thinking style is rational (“use your head”). Epstein (1994) contrasted such thinking styles, which are in fact central to the decision making literature (Kahneman, 2003). Pacini and Epstein (1999) then created a rational-experiential inventory to assess individual differences in preferences for these thinking styles. We hypothesized that heart-locators would prefer experiential thinking, whereas head-locators would prefer rational thinking. A double-dissociation of this type would greatly contribute to our understanding of individual differences in self-location.

Method

Participants, Procedures, and the Self-Location Measure

Participants were 117 (55 female) undergraduate students from NDSU seeking course credit. They were told that they would be completing a number of different tasks and questionnaires on computer. Sessions were conducted in groups of 6 or less and data were collected using MediaLab software. The self-location question was the same as in Study 1.

Outcome Measures

Participants completed the attention to emotion measure of Salovey et al. (1995). It presents individuals with 13 statements (e.g., “I pay a lot of attention to how I feel”) that are rated for their accuracy in characterizing the self (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Greater attention to emotion is consistent with valuing emotions to a greater extent (Palmieri, Boden, & Berenbaum, 2009). The scale was reliable (M = 3.57; SD = .52; Alpha = .77).

As indicated above, Pacini and Epstein (1999) created an inventory to assess individual differences in experiential and rational thinking styles. Each scale is composed of two subscales, one assessing preferences and the other assessing abilities. Our interest was in preferences for these two thinking styles and we therefore administered these preference-related items. Participants were asked the extent to which a series of 20 statements characterize the self (1 = definitely not true of myself; 5 = definitely true of myself). There were 10 experiential items (e.g., “I like to rely on my intuitive impressions”) and 10 rational items (e.g., “I enjoy intellectual challenges”). These scales have proven their worth in recent studies (e.g., Koele & Dietvorst, 2010). Both the experiential (M = 3.33; SD = .50; Alpha = .71) and rational (M = M = 3.27; SD = .62; Alpha = .78) scales were reliable.

Controlling for Openness to Experience

Individual differences in self-location are assessed in a very different manner than standard trait measures are. For example, the self-location measure does not directly ask people whether they are generally emotional, rational, warm, or anything of the sort. For such reasons, it also seems unlikely to us that individual differences in self-location can be equated with standard personality trait measures, which do in fact ask people direct questions about their personality tendencies (Pervin, 1994). Regardless, and although we will have more to say about such points later, it may be of utility to begin to make an empirical case for discriminant validity.

In personality psychology, there is now striking agreement on the fundamental traits of personality. These consist of extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience (John & Srivastava, 1999). These “big 5” traits organize and account for covariations between more specific trait measures (McCrae & Costa, 1999). For example, aggression is a variant of (low) agreeableness. In establishing discriminant validity for a new predictor like self-location, it can often be useful to control for a big 5 trait of most relevance to the outcomes assessed. In Study 2, openness to experience should be relevant to the outcomes because open people characterize themselves as deeper thinkers in both emotional and non-emotional realms (McCrae & Costa, 1999). We therefore assessed openness to experience (M = 3.44; SD = .54; Alpha = .76) using the well-validated 10 item scale of Goldberg (1999), which has a five-point (1 = very inaccurate; 5 = very accurate) rating format. Goldberg’s big 5 scales correlate very highly with alternative big 5 scales (John & Srivastava, 1999).

Results

Primary Results

The proportion of individuals choosing the heart (52%) versus the head (48%) as the location of the self was identical to Study 1. Thus, individuals differ dramatically and evenly in responding to this question. The percentage of women locating themselves in the heart was 62%, whereas the percentage of men locating themselves in the heart was 44%. A chi-square analysis of 2 (sex) x 2 (location) frequency counts replicated Study 1 in finding that sex was a significant predictor of heart versus head self-locations, χ2 = 3.90, p < .05.

A one-way ANOVA examined attention to emotion scores as a function of self-location. As hypothesized, heart-locators were higher in attention to emotion (M = 3.51) than head-locators (M = 3.10) were, F (1, 115) = 22.34, p < .01, partial eta square = .16. A multiple regression was then performed. Controlling for the overlap of the self-location and participant sex variables, both Self-Location (-1 = head; +1 = heart), b = .33, t = 4.20, p < .01, and Participant Sex (-1 = male; +1 = female), b = .38, t = 4.81, p < .01, predicted attention to emotion scores. Thus, variations in self-location constitute a novel predictor of valuing one’s emotions.

Heart-locators should also prefer experiential thinking to a greater extent. This hypothesis was confirmed in a one-way ANOVA in that experiential preferences were higher among heart-locators (M = 3.44) than head-locators (M = 3.21), F (1, 115) = 6.51, p < .05, partial eta square = .05. Pacini and Epstein (1999) found that a preference for experiential thinking was higher among women. This was so in the present study as well, but a multiple regression revealed Self-Location, b = .19, t = 2.14, p < .05, and Participant Sex, b = .21, t = 2.28, p < .05, to be independent predictors of preferences for experiential thinking.

Thus far, we have reported results concerning outcome measures that should be higher among heart-locators. A preference for rational thinking, though, should be higher among head-locators. This hypothesis was confirmed in a one-way ANOVA in that rational thinking preferences were higher among head-locators (M = 3.42) than heart-locators (M = 3.13), F (1, 115) = 6.52, p < .01, partial eta square = .05. Of additional importance, Pacini and Epstein (1999) found that a preference for rational thinking styles was not sex-linked. This was true in the present study as well. In a multiple regression, Self-Location predicted such preferences, b = −.25, t = −2.72, p < .01, whereas Participant Sex did not, b = .11, t = 1.14, p > .25. See Table 2 for correlations among the Study 2 measures.

Table 2.

Correlations among the Study 2 Measures

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-Location | ||||

| 2. Attention to Emotion | .40** | |||

| 3. Experiential Engage. | .23* | .51** | ||

| 4. Rational Engage. | −.23* | .18* | .12 | |

| 5. Openness to Exp. | −.11 | .21* | .18^ | .53** |

= p < .01;

= p < .05;

= p < .10

Controlling for Openness to Experience

As can be seen in Table 2, openness to experience predicted all of the outcomes of Study 2. We therefore performed multiple regressions in which we controlled for levels of this personality trait. After doing so, the Self-Location measure still predicted the attention to emotion, b = .22, t = 5.22, p < .01, experiential thinking, b = .13, t = 2.84, p < .01, and rational thinking, b = −.18, t = −2.26, p < .05, outcomes. Thus, discriminant validity was demonstrated with respect to openness to experience, the big 5 trait most relevant to the Study 2 outcomes. A further point can be made: Openness to experience did not predict self-locations (see Table 2) and therefore the self-location measure is not an alternative openness to experience measure.

Discussion and Study 3

The outcomes of Study 2 were different than those examined in Study 1 and generally focused on preferences for ways of feeling and thinking. Heart-locators reported paying greater attention to their emotions. Although doing so is sometimes functional (Salovey et al., 1995), it can be problematic in the context of ruminative tendencies (Gohm, 2003). Heart-locators also indicated a preference for intuitive-experiential thinking styles. This result is impressive in light of suggestions that this mode of thinking is not well-captured by trait-related conceptions of personality (Epstein, 1993).

Study 2 was the first to posit an outcome that should be higher among head-locators. As predicted, head-locators reported liking intellectual challenges to a greater extent. Subsequent studies will pursue the question as to whether head-locators are intellectually more skilled. For now, it is important to note that we were able to support a double-dissociation of thinking preferences in that heart-locators liked experiential thinking to a greater extent, whereas head-locators liked rational thinking to a greater extent. It is remarkable how well these results map onto metaphors linking the heart to intuitive thinking and the head to rational thinking (Kövecses, 2000; Lakoff & Johnson, 1999; Swan, 2009).

Study 3 sought to further establish a case for double-dissociations. Building on the results of Study 2, we would expect heart-locators to describe themselves as more emotional and head-locators to describe themselves as more logical. In examining such predictions, we created purpose-built self-report scales. Building on the results of Study 1, we would expect heart-locators to describe themselves as interpersonally warm and head-locators to describe themselves as interpersonally cold. In addition to purpose-built scales of warmth and coldness, we also administered a trait scale assessing agreeableness and hypothesized that levels of this trait would be higher among heart-locators than head-locators. Coldness, from an interpersonal perspective, should not be interpreted in terms of level-headedness or introspective tendencies, but rather in terms of less successful and antagonistic relationships with others (Moskowitz, 2010).

Method

Participants, Procedures, and the Self-Location Measure

Participants were 97 (53 female) undergraduate students from NDSU seeking course credit. They were told they would be asked a variety of different questions on computer. The self-location measure was the same as in Studies 1 and 2.

Outcome Measures

All outcome measures asked individuals whether they possessed certain personality attributes. In all cases, participants were asked the extent to which different statements accurately describe the self (1 = very inaccurate; 5 = very accurate). The instructions and rating scale were those of the International Personality Item Pool (Goldberg et al., 2006). We first sought to contrast emotional versus logical personal qualities. Three statements assessed emotionality (e.g., “I am emotional”). The scale was very reliable (M = 3.63; SD = .91; Alpha = .86). Three additional statements assessed the extent to which the individual could be described as logical (e.g., “I am logical”; M = 3.75; SD = .79; Alpha = .80). We second sought to contrast interpersonal warmth versus coldness. Three statements assessed warmth (e.g., “I am warm; M = 4.15; SD = .71; Alpha = .87) and three assessed coldness (e.g., “I am cold; M = 1.81; SD = .71; Alpha = .70).

Finally, participants completed Goldberg’s (1999) 10 item broad-bandwidth scale of agreeableness (e.g., “I sympathize with others’ feelings”). This scale correlates strongly with other big 5 agreeableness scales (John & Srivastava, 1999) and has been proven valid in many previous studies (e.g., Meier & Robinson, 2004b; Robinson & Gordon, 2011). The scale was reliable (M = 3.95; SD = .66; Alpha = .86). Concretely, agreeableness is an inverse predictor of anger and aggression (Wilkowski & Robinson, 2008), a robust predictor of cooperation in experimental studies (Graziano & Eisenberg, 1997), and it also predicts healthier and longer-lived personal relationships (Smith, Glazer, Ruiz, & Gallo, 2004).

Controlling for Trait Neuroticism

Study 3 included the big 5 trait of neuroticism for two reasons. First, we sought to examine whether neuroticism is related to self-locations. Second, neuroticism can be conceptualized as a type of emotionality, albeit one of a distress-related type (Watson, 2000). Controlling for neuroticism might be useful in establishing that heart-locators are emotional, but not because they are neurotic. We also controlled for neuroticism in follow-up analyses involving the other outcomes as well. Neuroticism was assessed using Goldberg’s (1999) scale, which has a range of 1 to 5 (M = 2.68; SD = .73; Alpha = .85).

Results

Primary Analyses

The percentage of individuals locating the self in the head (52%) versus heart (48%) represented a nearly even split. As in Studies 1 and 2, a majority of women were heart-locators (62%), whereas a minority of men were (32%). A chi-square analysis confirmed a significant relation between participant sex and self-location, χ2 = 8.92, p < .01.

Heart-locators should describe themselves as more emotional than head-locators. This prediction was confirmed in a one-way ANOVA (Ms = 3.89 & 3.39 for heart- & head-locators), F (1, 95) = 7.76, p < .01, partial eta square = .08. In a multiple regression, both Self-Location, b = .20, t = 1.99, p < .05, and Participant Sex, b = .24, t = 2.40, p < .05, predicted self-ascribed emotionality. By contrast, head-locators should describe themselves as more logical than heart-locators. This was also the case (Ms = 3.93 & 3.55 for head- & heart-locators), F (1, 95) = 5.91, p < .05, partial eta square = .06. In a multiple regression, Self-Location (−1 = head; +1 = heart) predicted such self-characterizations, b = −.25, t = -2.37, p < .05, whereas Participant Sex did not, b = −.02, t = −0.21, p > .80.

Interpersonal warmth should be higher among heart-locators. This prediction was confirmed in a one-way ANOVA (Ms = 4.35 & 3.96 for heart- & head-locators), F (1, 95) = 7.71, p < .01, partial eta square = .08. In a multiple regression controlling for participant sex, Self-Location was a marginal predictor of warmth, b = .19, t = 1.92, p < .10, and Participant Sex was a significant predictor, b = .27, t = 2.68, p < .01. On the other hand, head-locators should characterize themselves as higher in interpersonal coldness and they did (Ms = 1.99 & 1.61 for head- & heart-locators), F (1, 95) = 7.47, p < .01, partial eta square = .07. In a multiple regression, Self-Location predicted interpersonal coldness, b = −.23, t = −2.26, p < .05, whereas Participant Sex did not, b = −.12, t = −1.14, p > .25.

We finally hypothesized that heart-locators would score higher in agreeableness. This prediction was confirmed (Ms = 4.18 & 3.74 for heart- & head-locators), F = 11.85, p < .01, partial eta square = .11. In a multiple regression, Self-Location was a significant predictor of agreeableness, b = .27, t = 2.67, p < .01, as was Participant Sex, b = .22, t = 2.23, p < .05. In summary, multiple hypotheses from Study 3 were supported. Table 3 reports correlations among the measures.

Table 3.

Correlations among the Study 3 Measures

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-Location | ||||||

| 2. Emotional | .27* | |||||

| 3. Logical | −.24* | .02 | ||||

| 4. Warm | .27* | .40** | .18^ | |||

| 5. Cold | −.27* | −.18^ | .09 | −.53** | ||

| 6. Agreeable | .33** | .33** | −.03 | .43** | −.39** | |

| 7. Neuroticism | −.06 | .32** | −.09 | −.10 | .38** | −.05 |

= p < .01;

= p < .05;

= p < .10

Controlling for Neuroticism

As shown in Table 3, the big 5 trait of neuroticism did not predict self-locations. Thus, results involving the self-location variable should not be ascribed to this trait. Perhaps a stronger case for this point can be made by controlling for neuroticism in multiple regressions. When controlling for neuroticism, the Self-Location measure remained a significant predictor of the emotional, b = .27, t = 3.20, p < .01, logical, b = −.20, t = 2.50, p < .05, warm, b = .19, t = 2.71, p < .01, and cold, b = −.18, t = −2.67, p < .01, outcomes, as well as agreeableness, b = .22, t 3.40, p < .01. Thus, heart-locators are emotional, but not in a neurotic big 5 sense.

Discussion and Study 4

The major goal of Study 3 was to build on Study 2 in establishing further double-dissociations involving whether individuals view themselves as head- or heart-centric beings. Consistent with a first set of hypotheses, heart-locating individuals characterized themselves as more emotional, whereas head-locating individuals characterized themselves as more logical. Consistent with a second set of hypotheses, heart-locating individuals characterized themselves as warmer people, whereas head-locating individuals characterized themselves as colder people. These results, like those involving the experiential and rational scales of Study 2, suggest that our self-location assessment has considerable utility to the personality literature in contrasting types of people, at least with respect to double-dissociations.

Of further importance, we were able to establish that heart-locating individuals scored higher in agreeableness, an important trait in understanding individual differences in interpersonal functioning (Wilkowski & Robinson, 2008; 2010). In Study 6, we will further examine the role of self-locations in interpersonal functioning. Study 4, however, has a different purpose. Head-locating individuals, we suggest, may not only like intellectual activities more, but actually perform better in such activities. The rationale for this prediction is that more intelligent people, when thinking about the self, would be more likely to choose the body organ (i.e., the head) linked to intelligent performance. If so, we might expect them, relative to heart-locating individuals, to have higher GPAs. Furthermore, we might expect them to exhibit a greater degree of accuracy in answering general knowledge questions – a good, though not perfect, marker of intellectual capacity (Jensen, 1998).

Method

Participants, Procedures, and the Self-Location Measure

The same self-location assessment used in Studies 1–3 was used in Study 4 as well. Participants were 82 (38 female) undergraduate students from NDSU seeking course credit. They were told that they would respond to a series of very different questions on computer. As in the prior studies, sessions involved groups of 6 or less.

Outcome Measures

Participants were presented with 10 medium difficulty true/false general knowledge questions drawn from a popular Internet quiz website. They tapped historical knowledge (“Aphrodite is the Greek Goddess of War”: false), geographic knowledge (“Australia is the only continent that is also a country”: true), natural world knowledge (“There are over 20 colors in the rainbow”: false), real-world knowledge (“A stop sign is an octagon”: true), and vocabulary knowledge (“A bootlegger is someone who sells cigars”: false). The general knowledge questions were balanced such that five were true and five were false. For each statement, participants were to type “t” for true or “f” for false. The problems were in fact of medium difficulty in that the average accuracy rate was 79% (SD = 13%).

Participants were asked to report on their high school GPA and then their current college GPA. For both questions, they typed in a number with two decimal places (e.g., “3.23”). Previous research has shown that students have very accurate memories for their GPAs, even many years later (Bahrick, Hall, & Berger, 1996). Such estimates were therefore treated as likely veridical. High school GPA is an excellent predictor of college GPA, as it was in the present study. We therefore averaged across the two items (M = 3.13; SD = .48; Alpha = .72). Please note that these are objective (or nearly so in the case of reported GPA) outcomes and therefore immune to concerns as to whether reported self-locations might prime outcome responses. In this study, too, the outcomes were reported before the self-location measure was completed.

Results

There was a relatively even split of participants choosing the heart (54%) versus the head (46%) as the location of the self. A majority of women choose the heart as the location of the self (66%), whereas a minority of men did (46%). A chi-square analysis revealed that participant sex was a marginally significant predictor of self-location, χ2 = 3.02, p < .10. Added to the findings of Studies 1–3, however, there is little doubt concerning the robust nature of this sex difference.

We hypothesized that head-locators would possess greater general knowledge. To examine this prediction, we performed a one-way ANOVA on general knowledge accuracy rates. Head-locators were more accurate in answering these questions (M = 83%) than heart-locators were (M = 77%), F (1, 80) = 5.44, p < .05, partial eta square = .06. There is no compelling reason for thinking that general knowledge varies by sex, but a multiple regression was performed nonetheless. Self-Location continued to predict general knowledge performance with participant sex controlled, b = −.23, t = −2.09, p < .05, whereas Participant Sex was a non-significant predictor, b = −.11, t = −0.96, p > .30.

We also hypothesized that head-locators would possess higher GPAs. This prediction was confirmed in a one-way ANOVA (Ms = 3.27 & 3.05 for head- & heart-locators), F (1, 80) = 4.39, p < .05, partial eta square = .05. In a multiple regression, Self-Location remained a significant predictor of GPAs, b = −.23, t = −2.05, p < .05, whereas Participant Sex was a non-significant predictor, b = .00, t = 0.04, p > .95. See the top panel of Table 4 for correlations among the variables.

Table 4.

Correlations among the Study 4 Measures (Top Panel) and the Study 5 Measures (Bottom Panel)

| Measure | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-Location | ||

| 2. General Knowledge | .25* | |

| 3. GPA | .23* | .15 |

|

| ||

| Measure | 1 | 2 |

|

| ||

| 1. Self-Location | ||

| 2. Moral Dilemmas | .18* | |

| 3. Conscientiousness | −.08 | −.20* |

= p < .01;

= p < .05;

= p < .10

Discussion and Study 5

Study 2 found that head-locators liked intellectual activities to a greater extent. Study 3 found that head-locators characterized themselves as more logical. Such results, though, might reflect preferences rather than actual intellectual abilities or achievements. In Study 4, we were able to show that head-locators both (a) possess greater general knowledge and (b) have higher GPAs. The former measure’s strength is its link to general intelligence (Jensen, 1998), whereas the latter measure’s strength is its characterization of a long history of performance in the classroom. Taken together, the two findings of Study 4 complement each other in suggesting that head-locators appear to be somewhat more able in intellectual tasks and realms.

The results of Study 2 are suggestive of the idea that heart-locators may favor emotional considerations in social decision making, whereas head-locators may favor rational considerations in this same context. Study 5 sought to provide direct support for this idea. Such different modes of decision making can be excellently contrasted in moral dilemma scenarios (Bartels, 2008; Greene, 2011). In such dilemmas, an action by the self (e.g., to suffocate and kill a screaming baby) is emotionally aversive, but would result in a greater good to a larger number of people (e.g., by saving members of the community from hostile invaders). We hypothesized that heart-locators would solve such dilemmas in an emotional fashion, whereas head-locators would solve such dilemmas in a rational fashion.

Method

Participants, Procedures, and the Self-Location Measure

The Study 5 sample consisted of 127 (53 female) participants from NDSU seeking course credit. The study was again described as involving responses to very different questions, sessions consisted of groups of 6 or less, and data were collected by MediaLab software on personal computers. The self-location measure was the same one administered in Studies 1–4.

Outcome Measure

We presented participants with five classic moral dilemmas.5 We shortened the longer scenarios in favor of a briefer and more intuitive presentation of the key features of each dilemma. One scenario read as follows:

You are an inmate in a concentration camp. A sadistic guard is about to hang your son who tried to escape and wants you to pull the chair from underneath him. He says that if you don’t he will not only kill your son but some other innocent inmate as well. You don’t have any doubt that he means what he says. What would you do?

Responses for this scenario were q = “I would NOT pull the chair” and p = “I would pull the chair”. The first response is the emotional one as it is driven by aversion to the idea of killing one’s own son (Greene & Haidt, 2002). The second response is the rational one in that it would save an innocent person and one’s son would die in either case. We scored rational responses as 0 and emotional responses as 1 and then averaged across scenarios (M = .52; SD = .25).

Controlling for Conscientiousness

Conscientious people tend to be more thoughtful in their decision making (McCrae & Costa, 1999) and the outcome for this study related to decision making. For such reasons, we assessed the big 5 trait of conscientiousness and did so using Goldberg’s (1999) conscientiousness scale (M = 3.51; SD = .65; Alpha = .84).

Results

A relatively equal percentage of participants chose the heart (48%) versus the head (52%) as the locus of the self. The percentage of men choosing the heart was 41%, whereas the percentage of women choosing the heart was 58%. A chi-square analysis confirmed a significant association between participant sex and self-locations, χ2 = 3.99, p < .05.

The hypothesis of Study 5 was that heart-locators, relative to head-locators, would be more likely to solve moral dilemmas in an emotional manner. This prediction was confirmed in a one-way ANOVA, F (1, 126) = 4.13, p < .05, partial eta square = .03. On average, 53% of the dilemmas were solved in an emotional manner by heart-locators and 44% of the dilemmas were solved in an emotional manner by head-locators. In a multiple regression, Self-Location was a marginally significant predictor of emotional decision making, b = .16, t = 1.85, p < .10, whereas Participant Sex was a non-significant predictor, b = .12, t = 1.39, p > .10.

As shown in the bottom panel of Table 4, there was no systematic relationship between conscientiousness and the self-location measure. Further, when controlling for conscientiousness in a multiple regression, the Self-Location measure was a significant predictor of emotional responses to the moral dilemmas, b = .25, t = 2.26, p < .05. All told, we have now provided evidence that self-locations cannot be viewed as substitutes for the big 5 traits of openness, neuroticism, or conscientiousness. Additional related points will be made in the General Discussion.

Discussion and Study 6

The purpose of Study 5 was to pit emotional against rational considerations in social decision making. An excellent way of doing so is in the context of moral dilemmas in which one can actively harm another person, which is emotionally aversive, but in doing so save the lives of a greater number of people (Greene & Haidt, 2002). We found evidence that participants locating their selves in their hearts were more likely to solve such dilemmas in an emotional manner. This relationship, although significant in zero-order terms, was marginally significant with participant sex controlled. Accordingly, it was deemed best to replicate such findings in Study 6.

In addition, Study 6 had another purpose. To the extent that individual differences in self-location are substantive and important, they should predict responses to relevant events in daily life (Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003; Tennen, Affleck, Armeli, & Carney, 2000). We regard self-locations as potentially consequential to such everyday reactions. Accordingly, Study 6 was a daily diary study in which participants reported on daily events and potential reactions to them. On the basis of prior findings, and particularly those of Studies 1–3, we focused on the potential role of our self-location variable in moderating two event-outcome relationships.

First, our prior studies suggest that heart-locators should be more emotionally reactive. For example, Study 1 found that heart-locators scored higher in affect intensity and Study 3 found that heart-locators described themselves as more emotional. In daily diary protocols, emotional reactivity is typically examined in terms of negative emotional reactions to daily stressors (Compton et al., 2008; Suls & Martin, 2005; Tennen et al., 2000). We therefore assessed daily stressors and negative emotional experiences and hypothesized that higher levels of daily stress would predict higher levels of daily negative emotion to a greater extent among heart-locators than head-locators. Findings of this type would validate our suggestion that heart-locators are more emotionally reactive.

The second focus of the daily diary study was on a reaction that should be stronger among head-locators. Study 3 found that head-locators characterized themselves as cold and scored lower in agreeableness. There is considerable evidence that cold and disagreeable individuals react to provocation with higher levels of antisocial behavior or aggression (Bettencourt, Telley, Benjamin, & Valentine, 2006; Wilkowski & Robinson, 2010). Thus, we hypothesized that head-locators, relative to heart-locators, would act in a more antisocial fashion when provoked in their daily lives. Findings of this type would validate our suggestion that head-locators are disagreeable. Note that Study 6 examines reactions to social events and is not focused on the idea that head-locators are more logical or rational, which cannot be easily assessed in daily diary protocols.

Method

Participants, Laboratory Assessments, and Procedures

Participants registered for a two-part daily diary study. The first part was to be completed in the laboratory. In groups of 6 or less, 66 (25 female) NDSU participants receiving course credit (or monetary compensation for the daily protocol) completed the same self-location measure used in prior studies. They then responded to the same moral dilemmas used in Study 5. Again, rational choices were scored 0, emotional choices were scored 1, and we averaged across the five scenarios (M = .52; SD = .25).

Subsequent to the laboratory session, participants completed a 14 day diary protocol. Email reminders were sent to participants each morning at 9 a.m. Each daily survey was posted on the Internet after 5 p.m. and removed at 8 a.m. the next morning. In this way, we ensured that daily reports encompassed the day in question and could not be completed at a later time. The protocol automatically dropped people from the study if they had missed 4 of the daily reports. Among the completers of the study, compliance averaged 74% (range = 9–14 reports), for a total of 684 reports.

In previous studies, the self-location measure was completed in the same assessment session as the dependent measures. Such procedures render it possible that the relations obtained might depend on state-related factors or potential order effects. Such considerations are not relevant in relation to the daily outcomes of Study 6. There was at least a 3 day delay between completion of the laboratory portion of the study and the first daily survey, the self-location measure was one of many completed in the laboratory, the daily protocol was described generically, and the daily outcome predictions were subtle and unlikely to be discerned. Therefore, findings involving the daily outcomes should bypass concerns related to state-related effects or order effects, though this issue will be revisited in Study 8.

Daily Diary Survey and Analysis Strategy

The daily diary survey had to be brief because longer surveys would dissuade individuals from completing their daily reports (Bolger et al., 2003). Nonetheless, we sought to ensure that each daily assessment involved multiple items. We first assessed the extent (1 = not at all; 5 = extremely) to which the participant felt two markers of negative emotion (“distressed” & “nervous”) on each day. These markers were chosen from the PANAS negative affect scale (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) and have proven valid in previous studies of daily stress-reactivity (Compton et al., 2008). The daily negative emotion scale was reliable, as determined by first averaging across days and then performing a reliability analysis (M = 1.86; SD = .88; Alpha = .64). We therefore averaged across items, as we did for the other daily measures as well.

We then assessed antisocial behavior with a three-item survey that has proven reliable and valid in previous daily diary studies (e.g., Palder, Ode, Liu, & Robinson, in press). In specific terms, participants were asked the extent (0 = not at all true today; 3 = very much true today) to which they engaged in three antisocial behaviors (“argued with someone”, “insulted someone”, & “criticized someone”) on each day (M = .57; SD = .69; Alpha = .76). The daily outcome measures were assessed first to prevent their potential contamination by prior reports of daily events (Compton et al., 2008).

We then assessed the extent to which (1 = not at all true today; 4 = very much true today) four stressful events occurred each day (“had a deadline to worry about”, “had a lot of responsibilities”, “not enough time to meet obligations”, & “too many things to do at once”). Previous daily diary studies have shown that these particular stressors are common among undergraduate student populations and are predictive of negative emotions in daily life (Bresin, Fetterman & Robinson, 2012; Compton et al., 2008). The scale was reliable (M = 2.18; SD = .83; Alpha = .83). Finally, participants reported on the extent to which (1 = not at all true today; 4 = very much true today) they had been provoked each day in relation to two items (“someone argued with me” & “someone hurt my feelings”). These items have also been used in previous daily diary studies (e.g., Wilkowski, Robinson, & Troop-Gordon, 2010) and they constituted a reliable scale (M = 1.59; SD = .74; Alpha = .68).

In analyzing the daily diary data, we followed standard procedures. Heart-locators received a score of +1, whereas head-locators received a score of -1 (Aiken & West, 1991). The two event types –stressors and provocations– were person-centered such that their mean was 0 and their standard deviation was 1 (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). Intercepts and slopes were treated as random rather than fixed effects because they were hypothesized to vary across individuals (Tabachnic & Fidell, 2007). Analyses were based on multi-level modeling procedures, which are optimally suited for hypotheses and designs of the present type (Christensen, Barrett, Bliss-Moreau, Lebo, & Kaschub, 2003). Singer (1998) has advocated the use of the SAS PROC MIXED procedure for multi-level modeling analyses and we followed Singer’s recommendations for using this procedure.6

Results

Laboratory Results

The percentage of individuals choosing the heart (48%) versus the head (52%) as the locus of the self was almost exactly equal. Thus, self-locations are bifurcated in a manner that is noteworthy and potentially informative to multiple individual difference literatures. There was some tendency for women (M = 64%) relative to men (M = 39%) to view the heart rather than the head as the locus of the self, χ2 = 3.89, p = .05, replicating prior findings.

As in Study 5, we predicted that heart-locators (head-locators) would solve moral dilemmas in an emotional (rational) manner more frequently. This prediction was confirmed in a one-way ANOVA with Self-Location as the independent variable, F (1, 64) = 7.94, p < .01, partial eta square = .11 (Ms = 44% & 61% for head- & heart-locators respectively). In a multiple regression, both Self-Location, b = .24, t = 2.15, p < .05, and Participant Sex, b = .36, t = 3.21, p < .05, predicted the proportion of emotional resolutions to the dilemmas.

Daily Diary Results

A first multi-level modeling (MLM) analysis examined daily variations in negative emotion as a function of daily stressors, self-location, and their cross-level interaction. The predictors explained a significant amount of variance in negative emotion levels, χ2 = 264, p < .01. Consistent with the idea that stressors are a major cause of daily negative emotion (Watson, 2000), there was a main effect of Daily Stressors, b = .28, t = 6.19, p < .01. We hypothesized that heart-locators would exhibit greater reactivity to daily stressors, but not more intense negative emotions even on low stressor days. Consistent with such ideas, there was no main effect for Self-Location, b = .01, t = .11, p > .90. Consistent with the reactivity hypothesis, however, there was a significant cross-level interaction, b = .09, t = 2.09, p < .05.

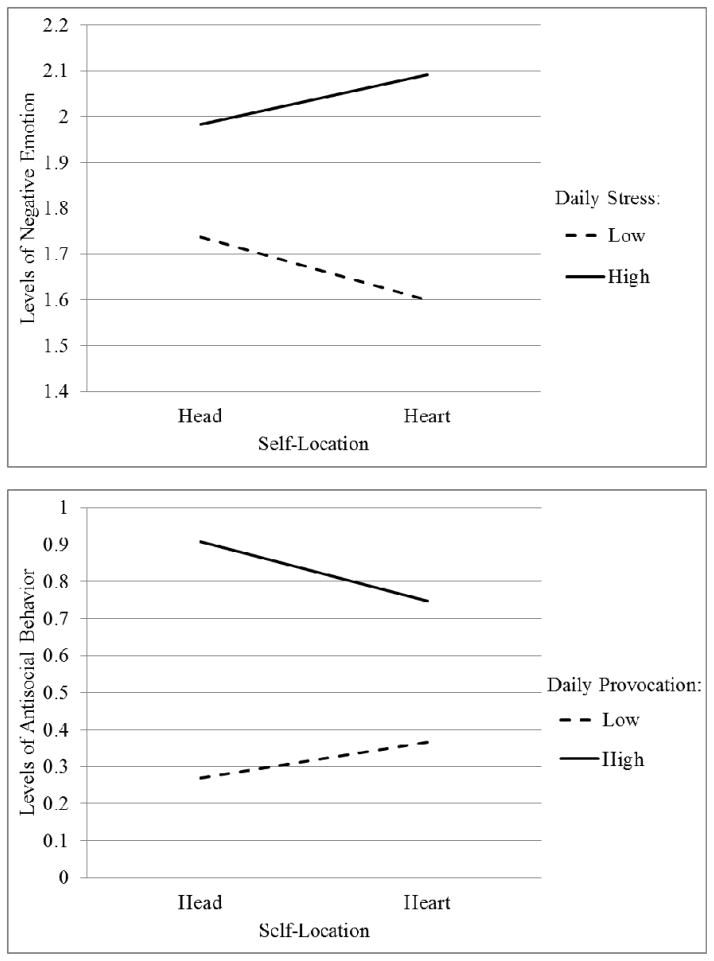

To understand the nature of the interaction, estimated means (Aiken & West, 1991) were calculated for low (−1 SD) versus high (+1 SD) stressor days for head-locators (−1 SD) and heart-locators (+1 SD). These estimated means are displayed in the top panel of Figure 1 and suggest that stress/negative emotion relations were stronger among heart-locators than head-locators. The relation between daily stressors and daily negative emotions was significant among both head-locators, b =.19, t = 3.83, p < .01, and heart-locators, b = .37, t = 5.30, p < .01, but was clearly stronger among heart-locators. That is, heart-locators exhibited greater negative emotional reactivity to stressors in daily life.

Figure 1.

Top Panel: Relations between Daily Stressors and Daily Negative Emotion among Head- versus Heart-Locators, Study 6; Bottom Panel: Relations between Daily Provocations and Antisocial Behavior among Head- versus Heart-Locators, Study 6

A second MLM analysis examined antisocial behaviors as a function of daily provocations, self-location, and their cross-level interaction. The predictors explained a significant amount of variance in antisocial behaviors, χ2 = 260, p < .01. Consistent with the idea that interpersonal provocation is a major cause of antisocial behavior (Berkowitz, 1993), there was a main effect for Daily Provocations, b = .43, t = 8.25, p < .01. We hypothesized that head-locators would act in an antisocial manner when provoked, but not necessarily in the absence of provocation. There was in fact no main effect for Self-Location, b = −.02, t = −.32, p > .70. Of more importance, there was a significant cross-level interaction, b = −.12, t = −2.09, p < .05.7

To understand the nature of this second cross-level interaction, estimated means were calculated for low (−1 SD) versus high (+1 SD) provocation days for head-locators and heart-locators separately considered. These estimated means are displayed in the bottom panel of Figure 1 and they suggest that the relation between provocation and antisocial behavior was stronger among head-locators than heart-locators. Daily levels of provocation predicted antisocial behavior among both heart-locators, b = .33, t = 4.14, p < .01, and head-locators, b = .54, t = 7.83, p < .01, but this relationship was clearly stronger among head-locators.

Discussion and Study 7

The most important laboratory result of Study 6 was that we were able to replicate the idea that heart-locators resolve moral dilemmas in an emotional manner. Accordingly, we suggest that heart-head metaphors (Kövecses, 2000; Swan, 2009) are far more than figures of speech. Rather, they govern or at least predict social decision making in cases in which emotional and rational considerations are in conflict. An additional purpose of Study 6, and one that we (e.g., Robinson & Neighbors, 2006) and others (e.g., Bolger et al., 2003; Tennen et al., 2000) view as particularly important, was to demonstrate that personality or individual difference variables have demonstrable consequences for understanding daily functioning.

In particular terms, we sought to show that heart-locators are more emotionally reactive to daily stressors, a result that would greatly extend the Study 3 finding that heart-locators described themselves as emotional. Additionally, we sought to show that head-locators act in an interpersonally cold or disagreeable manner when provoked (Smith, et al., 2004), a result that would greatly extend the Study 3 finding that head-locators described themselves as interpersonally disagreeable.

Both such daily diary predictions were confirmed. As might be expected, higher levels of daily stressors led to higher levels of daily negative emotion, but importantly such relations were stronger among heart-locators. Additionally, higher levels of daily provocation led to higher levels of antisocial behavior, but importantly such relations were stronger among head-locators. Heart- and head-locators, then, are reactive to different types of events, in relation to different outcomes, but in a manner suggesting that heart-locators are more emotionally reactive, whereas head-locators are disagreeable in their interpersonal functioning.

Thus far, our results have been correlational in nature. This is not a problem, but rather a strength, from an individual differences perspective. On the other hand, manipulation studies may resolve some ambiguities and we deemed it useful to include such a study. Therefore, Study 7 sought to manipulate attention toward the heart or the head in an experimental manner. This manipulation randomly assigned participants to two conditions, one in which people were surreptitiously led to point to the head and one in which they were surreptitiously led to point to the heart. As indicated below, the manipulation was subtle and its effects cannot therefore be ascribed to semantic priming effects. Additionally, the manipulation did not require participants to locate the self in either body organ and was subtle in this manner too. Asking people to locate the self in the head or the heart prior to the outcomes was deemed potentially too high in demand characteristics. Nonetheless, and given that the self is psychologically a bodily entity (Burris & Rempel, 2004; Robinson et al., 2006), we thought it likely that the self would “travel” to the organs pointed to and influence outcomes for this reason.

In understanding the effects of this manipulation, we decided to focus on two outcomes. First, we examined whether this manipulation would influence decision making in moral dilemmas of the type used in Studies 5 and 6. We hypothesized that heart-pointers would resolve such dilemmas in more emotional terms. Second, we hypothesized that head-pointers would answer general knowledge questions –of the sort assessed in Study 4 –more accurately. The latter result would be remarkable if performance on such questions is solely determined by crystallized intelligence (Buehner, Krumm, Ziegler, & Pluecken, 2006), but there are in fact precedents for the idea that priming factors can influence performance on such questions (e.g., Dijksterhuis, Bargh, & Miedema, 2000). Accordingly, and because the head is the metaphoric locus of intellectual knowledge (Swan, 2009), head-pointing may improve general knowledge performance, in Study 7 as a function of metaphoric processes.

Method

Participants and General Procedures

Participants consisted of 74 (42 female) undergraduates from NDSU seeking course credit. The study was generally described as one involving a number of unrelated tasks. Participants completed the study on personal computers in groups of 6 or fewer.

Manipulation

Upon entering the laboratory, all participants were informed that we were interested in how people answer questions when using their dominant or non-dominant hands. They were further told that they were in the non-dominant hand condition. We emphasized the fact that people often end up using their dominant hands, even when instructed not to do so, because doing so is such a habitual occurrence. To prevent this possibility, we stated, it was necessary to occupy the dominant hand with another task. Accordingly, the dominant hand, and particularly its index finger, was to be placed on a part of the body to preclude its use while answering questions on the computer.

Participant sessions were randomly assigned to one of the two metaphor-related conditions. In the head condition, participants were told to place their dominant index fingers on the corresponding side of the temple. We did not mention the word “head” because we wanted to avoid semantically (or verbally) priming this word. The experimenter modeled this placement and ensured that dominant index fingers were placed appropriately. In the heart condition, participants were told to place their dominant index fingers over the left portion of the upper chest. The experimenter modeled this placement and ensured that dominant index fingers were touching this body area, which contains the heart. In both conditions, participants were instructed to continue the gesture while answering questions.

Dependent Measures

We obtained a set of 8 true-false general knowledge statements for use in Study 7. These included “About one-sixth of the earth’s surface is permanently covered with ice” (false) and “Alaska, with 8, is the US state with the most national park sites” (true). Four statements were true and 4 were false, ensuring that greater accuracy could not be obtained by generally responding true or false. In contrast to Study 4, the general knowledge questions were harder (M accuracy = 51%; SD = 18%). This was intentional in that our focus was on manipulation effects rather than pre-existing knowledge (Dijksterhuis et al., 2000). Importantly, however, logical reasoning would at least be helpful in classifying the statements as true or false. For example, Alaska is a very large state with abundant natural resources and it therefore makes sense that this state contains more national parks than other states in the US. Participants typed “t” for true and “f” for false.8

Subsequently, the same moral dilemmas presented in Studies 5 and 6 were presented in Study 7 as well, this time in the context of the metaphor-related manipulation of pointing toward one body part versus the other. Scenario solutions were presented laterally and required pressing the q or the p key of the keyboard. As in prior studies, rational responses to the dilemmas were scored as 0, emotional responses were scored as 1, and we then averaged responses across the dilemmas (M = .49; SD = .23).

Results

We hypothesized that head-pointers, relative to heart-pointers, would exhibit greater accuracy when deciding whether general knowledge statements were true or false. This prediction was confirmed in a one-way ANOVA, F (1, 72) = 4.16, p < .05, partial eta square = .05, a medium effect size (Ms = 47% & 56% for heart- & head-pointers, respectively). When controlling for participant sex in a multiple regression, the manipulation effect remained significant, b = −.26, t = −2.27, p < .05.

By contrast, we hypothesized that heart-pointers, relative to head-pointers, would solve moral dilemmas in an emotional manner. This prediction was confirmed in a second one-way ANOVA, F (1, 72) = 4.06, p < .05, partial eta square = .05, again a medium effect size (Ms = 44% & 54% for head- & heart-pointers, respectively). When controlling for participant sex in a multiple regression, the manipulation effect remained significant, b = .23, t = 2.02, p < .05.

Discussion

Our primary interest in the investigation was individual differences. On the other hand, we recognize that manipulation studies are useful in parsing cause and effect. The results of Study 7 are therefore important in showing that drawing attention to the head facilitates intellectual problem solving, likely because it leads people to reason through the problems to a greater extent. By contrast, drawing attention to the heart leads to weighting emotional over rational factors in decision making, likely because it increases the salience of one’s feelings when deciding what one would do. Based on additional results from Studies 1–6, we advocate metaphor-related manipulations of the present type in understanding experiential thinking (which should be increased by heart-pointing), interpersonal coldness (which should be increased by head-pointing), and emotional reactivity (which should be increased by heart-pointing).

There was no control condition in Study 7 in the sense that both the head- and heart-pointing conditions were theory-relevant. A control condition would have been difficult to instantiate in the context of the cover story (i.e., precluding the use of the dominant hand by placing it on a portion of the body). Further, Studies 1–6 found that, in the absence of a manipulation, people differ in their self-locations and therefore a control condition in Study 7 would arguably have been messy from a self-location perspective. In addition, the manipulation provided maximal power in relation to two body organs that are metaphorically linked to quite different functions and outcomes (Swan, 2009). All such points aside, we can see the value to control conditions in designs of the Study 7 type and therefore advocate them in understanding the unique effects of head- versus heart-pointing in future studies.

Study 8

Study 6, in the examination of daily outcomes assessed at least 3 days later, argues in favor of the predictive validity of self-locations over time. Nonetheless, we recognize that the delay between the completion of the self-location measure and the daily outcomes consisted of weeks at most. Accordingly, Study 8 sought to examine the predictive validity of self-locations over a longer period of time. In addition, the Study 8 protocol also sought to assess the stability of self-locations themselves. We hypothesized that self-locations would be consistent over a very long time period and, more importantly, hypothesized that individual differences in self-location, assessed at time 1, would predict multiple personality-related variables – those also assessed in Study 3 –at time 2, almost a year later. Results of this type would greatly extend the idea that self-locations are dispositional in nature. We do mention that the sample size for this study was not large, but that the findings represented an important inclusion to the paper.

Method

Time 1 Assessment

Participants from NDSU initially completed a number of measures and tasks in laboratory sessions of 6 or less. Whether people located the self in the head or the heart was not of theoretical interest to the study proper, but –fortunately– this measure had been administered. The item was exactly that described in Studies 1–6. At time 1, 58% of the participants located the self in the heart. Additionally, there was a sex difference consistent with prior studies such that the percentage of woman who were heart locators (72%) was larger than the percentage of men who were heart locators (46%), χ2 = 12.59, p < .01.

Time 2 Assessment

Participants were contacted by email at least 282 days subsequent to completing the initial laboratory session. No mention was made of self-locations and, in fact, these participants had completed a large number of measures at time 1. Participants were asked whether they would complete a “follow-up” study, which was entirely voluntary, but would be compensated by $7. Three email reminders were sent, which ultimately resulted in a time 2 sample size of 36 (22 female), a small minority of the time 1 sample. These participants completed a survey over the Internet using Survey Monkey.

The time 2 outcomes consisted of the emotional (M = 3.71; SD = .97; Alpha = .86), logical (M = 4.08; SD = .79; Alpha = .84), warmth (M = 4.17; SD = .91; Alpha = .93), coldness (M = 1.77; SD = .93; Alpha = .88), and agreeableness (M = 4.08; SD = .77; Alpha = .90) scales of Study 3, exactly as administered in that study. Participants had to make all of these ratings and then had to press enter to go to the final screen. On the final screen, and for purposes of analyzing test-retest stability rather than outcome prediction, the self-location measure was completed again.

Results

Consistency in Self-Locations across Time

We classified people as consistent in their self-locations across time or as switchers. There was a larger number of people who remained consistent (27) rather than switched (9) their self-locations, χ2 = 9.00, p < .01, Cramer’s V = .50. Thus, perceived self-locations are generally consistent even across a very long time frame.

Outcome Prediction

An important question in personality psychology is whether assessments at one time can predict time 2 outcomes even when there is a long intervening time interval (Ozer & Benet- Martinez, 2006). In the present context, this is a conservative analysis strategy because we know that a small minority of individuals did switch their self-locations and the time 2 self-location measure was more contemporaneous with the outcome measures. We do note that the results below are even stronger when switchers are excluded and are substantially the same when the time 2 self-location measure is used instead. Nonetheless, we chose to report the results of the most conservative test – i.e., the time 1 self-location measure predicting the time 2 outcomes, with the entire sample included.

The sample size was not large, however, and we therefore sought to increase power when it made sense to do so. The emotional and logical outcomes form a pair as do the warmth and coldness outcomes. For each of these pairs of outcomes, moreover, we predicted a cross-over interaction. For example, heart-locators should score higher on the emotional scale, whereas head-locators should score higher on the logical scale. For these pairs of outcomes, then, we performed mixed-model ANOVAs. The between-subjects factor was self-location and the within-subject factor was scale (e.g., emotional versus logical).

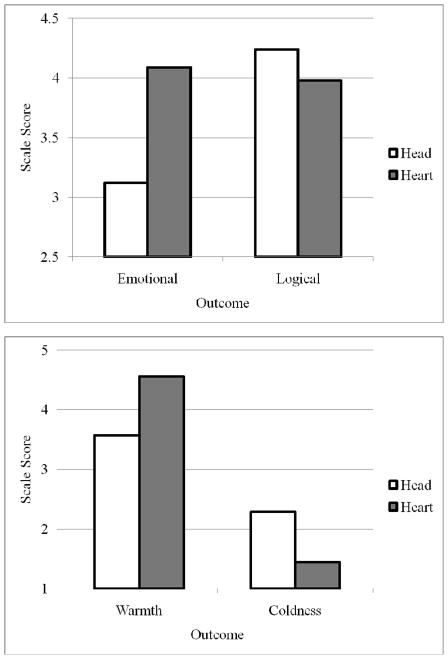

In contrasting emotional and logical personality attributes, the main effect for Self-Location was not significant, F < 1. The Scale factor was significant, F (1, 34) = 5.51, p < .05, partial eta square = .14, in that scores for the logical scale were higher (M = 4.11) than the scores for the emotional scale (M = 3.61) in the sample as a whole. Of more importance, there was a Self-Location by Scale interaction, F (1, 34) = 8.05, p < .01, partial eta square = .19. Means for this interaction are reported in the top panel of Figure 2. As shown there, and as hypothesized, there was a cross-over interaction such that heart-locators reported themselves to be more emotional, whereas head-locators reported themselves to be more logical. In a follow-up multiple regression, we created an emotional minus logical difference score and then entered the self-location and participant sex variables. Both Self-Location, b = .38, t = 2.54, p < .05, and Participant Sex, b = .34, t = 2.31, p < .05, predicted tendencies to view oneself as more emotional than logical with overlap among these predictors controlled.

Figure 2.

Top Panel: Self-Locations as a Predictor of the Qualities of Emotional versus Logical, Study 8; Bottom Panel: Self-Locations as a Predictor of the Qualities of Warmth versus Coldness, Study 8

In contrasting warmth and coldness, there was again no main effect for Self-Location, F < 1. As might be expected, however, warmth scores (M = 4.06) were higher than coldness scores (M = 1.87), F (1, 34) = 70.87, p < .01, partial eta square = .68, as warmth is the more normative personality attribute (Wiggins & Trapnell, 1996). There was also a Self-Location by Scale interaction, F (1, 34) = 12.18, p < .01, partial eta square = .26. The relevant means are displayed in the bottom panel of Figure 2. As shown there, warmth scores were higher among heart-locators and coldness scores were higher among head-locators. In a follow-up multiple regression, we created a warmth minus coldness difference score and then treated it as a dependent measure in a multiple regression. Self-location was a strong predictor, b = .89, t = 3.31, p < .01, whereas Participant Sex was not, b = .13, t = 0.57, p > .60.

Agreeableness was not paired with any other personality attribute and we therefore conducted a simpler one-way ANOVA in examining this outcome. The main effect for Self-Location was significant, F (1, 34) = 5.19, p < .01, partial eta square = .25. As hypothesized, and even after a long intervening interval, heart-locators scored higher in agreeableness (M = 4.39) than head-locators did (M = 3.61). A multiple regression revealed that Self-Location remained a significant predictor of agreeableness with participant sex controlled, b = .37, t = 3.15, p < .01, whereas Participant Sex was a non-significant predictor, b = .08, t = 0.69, p > .45. See Table 5 for correlations among the Study 8 variables.

Table 5.

Correlations among the Study 8 Measures

| Measure | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Self-Location | |||||

| 2. Emotional | .49* | ||||

| 3. Logical | −.16 | −.22 | |||

| 4. Warm | .53** | .64** | .13 | ||

| 5. Cold | −.45** | −.52** | −.14 | −.82** | |

| 6. Agreeable | .50** | .74** | .01 | .76** | −.69** |

= p < .01;

= p < .05;

= p < .10

Discussion