Abstract

We demonstrated that in the yeast Hansenula polymorpha peroxisome fission and degradation are coupled processes that are important to remove intra-organellar protein aggregates. Protein aggregates were formed in peroxisomes upon synthesis of a mutant catalase variant. We showed that the introduction of these aggregates in the peroxisomal lumen had physiological disadvantages as it affected growth and caused enhanced levels of reactive oxygen species. Formation of the protein aggregates was followed by asymmetric peroxisome fission to separate the aggregate from the mother organelle. Subsequently, these small, protein aggregate-containing organelles were degraded by autophagy. In line with this observation we showed that the degradation of the protein aggregates was strongly reduced in dnm1 and pex11 cells in which peroxisome fission is reduced. Moreover, this process was dependent on Atg1 and Atg11.

Keywords: yeast, peroxisome, protein aggregate, fission, autophagy

Introduction

Cellular homeostasis depends on a large array of quality control processes, which are important for the recognition and removal or repair of cellular components. Detailed knowledge of such processes is of major medical relevance as they are the molecular basis of devastating diseases such as cancer,1 Alzheimer and Parkinson diseases.2-4 Quality control processes include refolding of unfolded polypeptides by molecular chaperones5 as well as proteolysis of individual proteins, protein aggregates or cell organelles.6,7

A well-studied cytosolic proteolytic system is the ubiquitin-proteasome machinery for the degradation of polypeptides. Endoplasmic-reticulum-associated protein degradation is responsible for the export of aberrant proteins from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum followed by cytosolic degradation by the proteasome.8 In both mitochondria and peroxisomes, intra-organellar proteases have been identified that are crucial for the proteostasis of these organelles.9

Autophagy is involved in the degradation of larger cellular compounds, such as protein aggregates, ribosomes, pieces of cell organelles (e.g., piecemeal microautophagy of the nucleus/micronucleophagy) or entire organelles.7 In yeast, autophagy is induced under starvation conditions as a means to recycle unnecessary cellular components in order to allow the cell to synthesize essential new ones.10 However, this process also serves as a cellular quality control system to remove redundant, aberrant or toxic cell constituents.

Autophagic degradation of peroxisomes has been extensively studied in the yeast Hansenula polymorpha. In this organism different peroxisome degradation processes can be distinguished. The first one is glucose-induced selective macroautophagy (macropexophagy), which serves to degrade peroxisomes containing enzymes that are redundant for growth. Second, under nitrogen starvation conditions, peroxisomes are degraded by nonselective microautophagy.11 Finally, constitutive autophagic degradation of peroxisomes has been described and occurs during normal vegetative growth of the cells, likely as a mode to continuously rejuvenate the organelle population.12 Consistent with this, an autophagic quality control mechanism exists that most likely triggers the removal of dysfunctional or aberrant peroxisomes.

To further analyze this phenomenon we stimulated the formation of aberrant peroxisomes in H. polymorpha by introducing protein aggregates in the organelle matrix. This approach recently became feasible as we observed that the production of a mutant variant of peroxisomal catalase (containing a mutation in the heme binding site as well as the strong peroxisomal targeting sequence—SKL) results in the formation of large intra-organellar protein aggregates.13 Protein aggregates are well known for being toxic in eukaryotic cells. Their accumulation often causes the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), a major cause of aging.14

Recently, a quality-control mechanism has been proposed in which mitochondrial fission, fusion and selective autophagic degradation (mitophagy) cooperatively prevent the accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria.15,16 This poses the question as to whether comparable mechanisms exist for peroxisomes to remove aberrant parts of the organelles. In turn, this prompted us to investigate the putative role of peroxisome fission (these organelles do not fuse17,18) and degradation in removing aberrant peroxisomes that contained lumenal protein aggregates.

First, we showed that the accumulation of these aggregates affects growth and results in enhanced levels of ROS. Next, we demonstrated that peroxisome fission is important for both glucose-induced pexophagy as well as for constitutive pexophagy. Finally, we showed that peroxisomal protein aggregates are removed from the organelles by a Dnm1- and Pex11-dependent asymmetric peroxisome fission process, followed by degradation of the smaller aggregate-containing organelles.

Results

Peroxisome fission is important for degradation

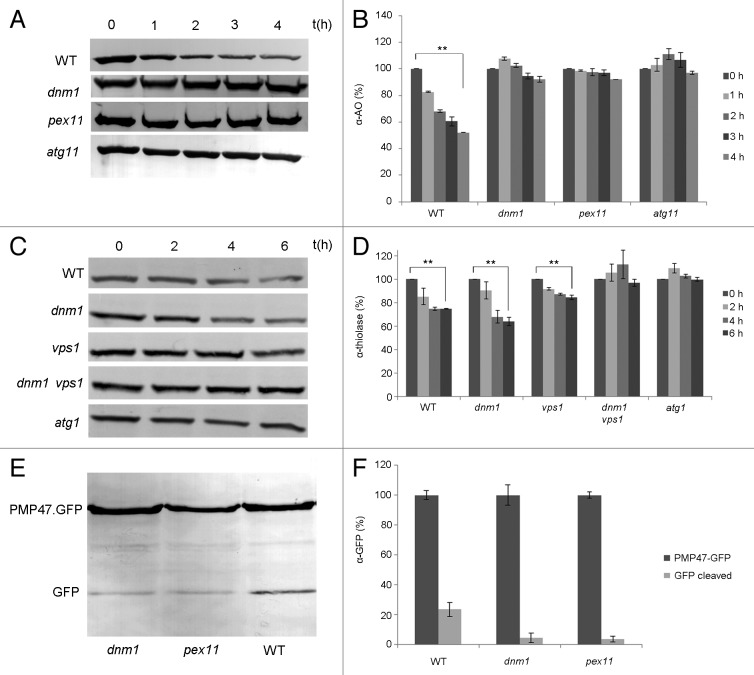

To analyze whether peroxisome fission is important for glucose-induced selective peroxisome degradation (macropexophagy), we analyzed this process in wild-type H. polymorpha as well as in two mutant strains (dnm1 and pex11) that are strongly impaired in peroxisome fission.19,20 In line with earlier observations, the levels of the peroxisomal marker protein alcohol oxidase (AO) gradually decreased in the wild-type control upon induction of macropexophagy by glucose (Fig. 1A and B). However, in both dnm1 and pex11 cells, no significant reduction of AO protein levels was observed. A similar result was obtained in the atg11 control strain, which is defective in selective pexophagy.21 These results suggest that a reduction in peroxisome fission affects glucose-induced macropexophagy.

Figure 1. Reduced peroxisome degradation in H. polymorpha and S. cerevisiae fission mutants. (A) Pexophagy was induced by glucose in H. polymorpha cells grown for 20 h on methanol. Equal volumes of cultures were loaded per lane. Western blots decorated with anti-alcohol oxidase (α-AO) antibodies show no significant reduction in AO levels in the peroxisomal fission mutants dnm1 and pex11, similar to the atg11 control, which is blocked in pexophagy, whereas AO levels gradually decreased in the wild-type control as expected. (B) Densitometry quantification of the blots shown in (A). The amount of AO protein present at t = 0 h was set to 100%. The bar represents the standard error of the mean (SEM). (**p < 0.01). (C) Western blot analysis showing thiolase levels of S. cerevisiae cells grown on oleate and subsequently diluted into SD(-N) medium to induce peroxisome degradation. Samples were harvested at different time points, and equal amounts of protein were loaded per lane. There is no significant decrease of thiolase in the dnm1∆ vps1∆ double mutant where the peroxisomal fission is completely blocked. A similar result was obtained for the atg1 control strain. In the wild-type and the single vps1 and dnm1 deletion strains degradation occurred. (D) Quantification of thiolase blots shown in (C). The level of thiolase protein at t = 0 h was set to 100%. Levels were adjusted to the loading control glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (not shown). The bar represents the SEM (**p < 0.01). (E) Constitutive peroxisome degradation is reduced in H. polymorpha fission mutants. Cells were grown on methanol for 16 h. Western blots were prepared using crude extracts and anti-GFP antibodies to detect Pmp47-GFP and GFP degradation products. The data show that the levels of the cleaved fusion protein (lower band) are reduced in pex11 and dnm1 cells, relative to the wild-type control. Equal concentrations of protein were loaded per lane. (F) Quantification of blots shown in (E). The levels of full-length Pmp47-GFP proteins were arbitrarily set to 100%. The levels of cleaved GFP (lower band) are indicated as percentage of the full-length fusion protein. The bar represents the SEM (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01).

To rule out that the observed block in pexophagy is not related to the fission defect in H. polymorpha dnm1 or pex11 cells, but related to a direct function of fission proteins in pexophagy, we performed a control study using Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Different from H. polymorpha, in baker’s yeast, Dnm1 and Vps1 have redundant functions in peroxisome fission. Consequently, single dnm1 and vps1 mutants are only partially affected in peroxisome fission and thus can be analyzed for a direct function of these proteins in pexophagy.22 As shown in Figure 1C and D, single S. cerevisiae dnm1 and vps1 mutants were not blocked in glucose-induced pexophagy, whereas cells of the dnm1 vps1 double mutant, which has a major peroxisome fission defect, were impaired in peroxisome degradation.

Using an H. polymorpha strain that produces the peroxisomal membrane protein Pmp47 fused to green fluorescent protein (Pmp47-GFP), we analyzed constitutive peroxisome degradation in methanol-grown cells of H. polymorpha wild type and both dnm1 and pex11 mutant strains using western blot analysis and anti-GFP antibodies (Fig. 1E). As expected, in extracts of wild-type cells in addition to the band representing the full-length Pmp47-GFP fusion protein, a faster migrating band consisting of cleaved GFP was also evident, indicative of constitutive pexophagy. The ratio of the amount of cleaved GFP relative to the full-length fusion protein was reduced in dnm1 and pex11 cells compared with wild-type controls (Fig. 1F), indicating that constitutive autophagy of peroxisomes is also affected in H. polymorpha pex11 and dnm1 cells.23 Summarizing these data indicates that in yeast peroxisome fission is required for pexophagy.

Intra-peroxisomal protein aggregates affect growth and cause oxidative stress

Next, we addressed whether peroxisome fission acts in quality control of the organelles. For this we took advantage of earlier observations that production of a mutant variant of catalase, designated Catmut, produced in wild-type H. polymorpha (i.e., also producing the endogenous catalase protein) forms enzymatically inactive protein aggregates in the peroxisomal lumen.13 Peroxisomes containing these protein aggregates were used as a model for aberrant peroxisomes in this study.

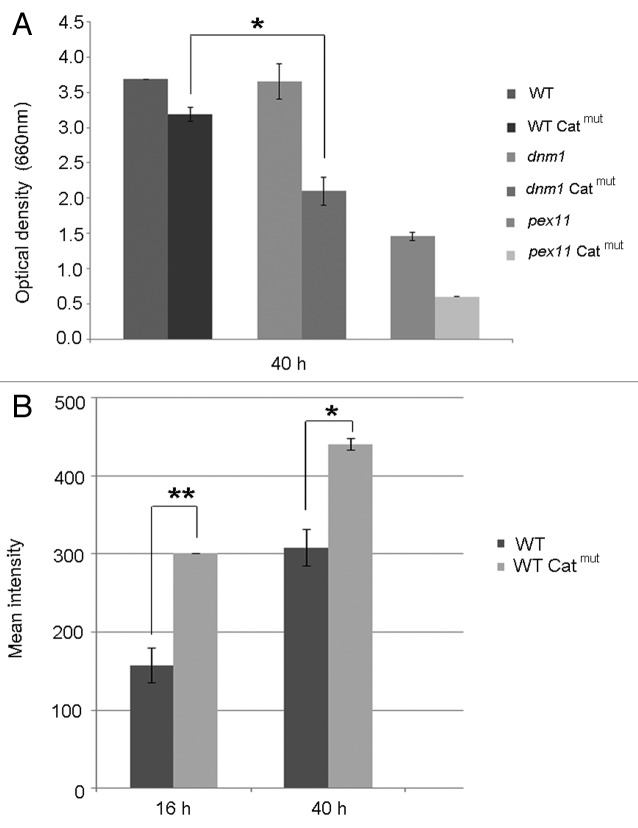

First, we tested whether the presence of peroxisomal protein aggregates had physiological consequences. As shown in Figure 2A cultures of the Catmut strain showed a reduced yield. Remarkably, the specific catalase activities in cell extracts of cells of the Catmut strain (185 U/mg) were enhanced relative to that of the wild-type control (130 U/mg). ROS measurements indicated that at all time points examined, the cells containing peroxisomal protein aggregates had enhanced ROS levels relative to the wild-type control (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. The effect of peroxisomal protein aggregates on growth and ROS levels. (A) Final optical densities of wild-type, dnm1 and pex11 cells, producing or not producing Catmut, upon growth on methanol as sole carbon source for 40 h. Cell were extensively precultivated in glucose medium and subsequently shifted to medium containing methanol. Final optical densities are expressed as adsorption at 660 nm. The bar represents the SEM (*p < 0.05). (B) ROS levels in cells at different time points after the shift of glucose-grown cells to methanol medium. The mean intensity was measured by FACS. Catmut cells show an enhanced ROS production relative to wild-type controls. The bar represents the SEM (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01).

Intraperoxisomal protein aggregates are removed by fission and degradation

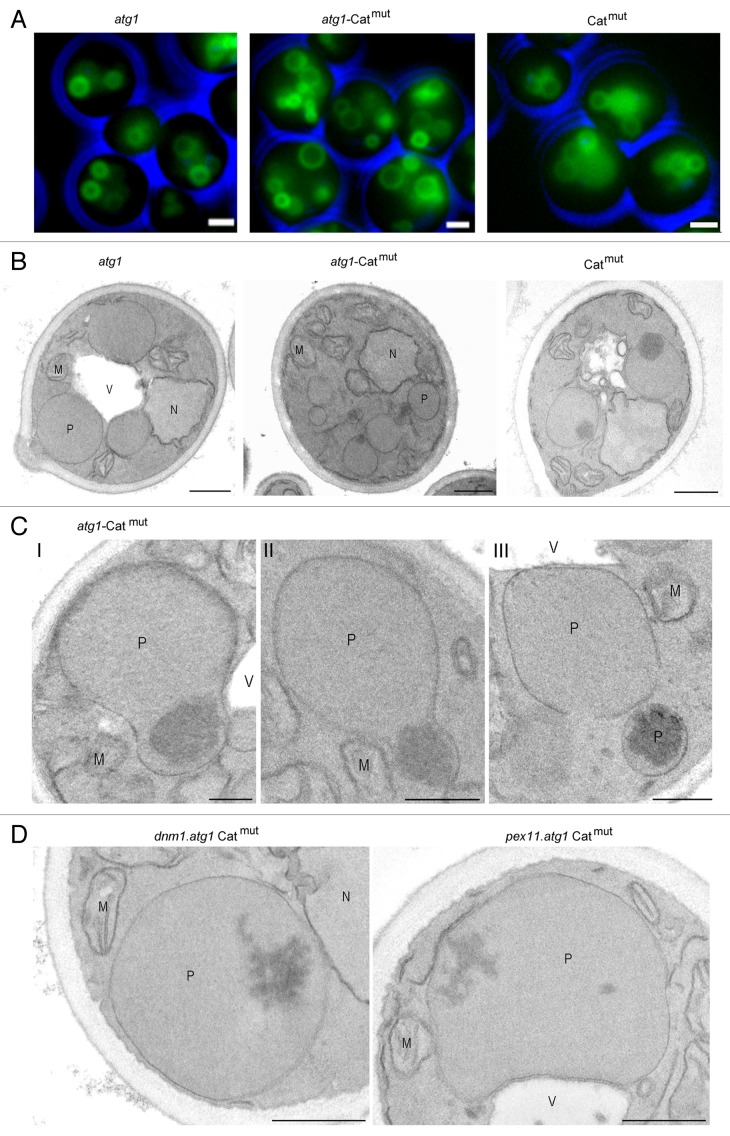

To substantiate whether the protein aggregates induce peroxisome fission, we introduced Catmut in the H. polymorpha atg1 mutant, in which autophagic degradation of peroxisomes is blocked.24 In order to visualize peroxisomes we introduced the fluorescent peroxisomal membrane marker Pmp47-GFP. Fluorescence microscopy analyses of cells, cultivated for 16 h on methanol, revealed that the Catmut-producing atg1 strain contained, in addition to the normal organelles, relatively small organelles that were not observed in the atg1 parental strain (Fig. 3A). This result was confirmed by electron microscopy analysis of KMnO4-fixed cells (Fig. 3B) and also showed the presence of aggregates in the small organelles (Fig. 3B). Subsequent analysis, however, revealed that small organelles were not evident by fluorescence microscopy of wild-type cells producing Catmut (Fig. 3A), whereas electron microscopy revealed that these cells harbored fewer small aggregate-containing peroxisomes relative to the atg1 strain producing Catmut. Apparently, the small separated organelles were rapidly removed in the wild-type background. This process was further analyzed by electron microscopy. These analyses revealed that once formed, aggregates migrated to the periphery of the organelle where they were included in the buds that subsequently split off from the mother organelle (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3. Microscopy analysis of H. polymorpha atg1, atg1-Catmut and wild-type-Catmut cells. Cells were grown on glycerol/methanol for 16 h. Peroxisomal membranes are marked by Pmp47-GFP. (A) Relative to the atg1 control, the atg1-Catmut strain contains multiple small peroxisomes, which was not evident in wild-type-Catmut cells. The bar represents 1 µm. The peroxisomal phenotype was confirmed by electron microscopy (B). Note the presence of protein aggregates in many of the organelles in atg1-Catmut cells of which fewer are observed in wild-type-Catmut cells. The bar represents 0.5 µm. (C) Ultrathin sections of KMnO4-fixed atg1-Catmut cells showing different stages of the formation of a small peroxisome containing a protein aggregate. The bar represents 0.2 µm. (D) Electron micrographs, showing details of dnm1.atg1 cells (left panel) and pex11.atg1 cells (right panel) producing Catmut, demonstrating the presence of aggregates in the enlarged peroxisomes in these cells. The bar represents 0.2 µm. P, peroxisomes; M, mitochondria; N, nucleus; V, vacuole.

To further address their degradation, we cultivated the H. polymorpha Catmut strain on a mixture of glycerol/methanol and subsequently administered 1 mM of the protease inhibitor phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride (PMSF) to the culture to reduce the rate of degradation of autophagic bodies in the vacuole. Electron microscopy analysis of these cells showed that at the onset of the experiment vacuoles in Catmut-producing cells contained very low numbers of autophagic bodies (Fig. 4A and B). However, after 2 (Fig. 4C and D) and 4 h (Fig. 4E and F) of PMSF administration the accumulation of aggregate containing organelles in the vacuole was evident. These structures were not observed in the wild-type control. The presence of catalase protein was confirmed by immunocytochemistry (Fig. 4G and H). These data suggest that peroxisomes with protein aggregates are delivered to the vacuole for autophagic degradation. In conclusion, we showed that protein aggregates, which accumulated in the peroxisomal lumen are removed by concerted fission and degradation events.

Figure 4. Catalase aggregates are degraded by autophagy. H. polymorpha wild-type and Catmut cells were cultivated on glycerol/methanol for 12 h and subsequently treated with 1 mM PMSF (t = 0). Electron micrographs of KMnO4-fixed Catmut cells [at t = 0 h (B)], [at t = 2 h (D) and t = 4 h (F)] revealed progressive accumulation of autophagic bodies containing peroxisomes with protein aggregates that are not observed in wild-type cells (A, C and E). Immunocytochemical localization of catalase shows that labeling is confined to peroxisomes of wild-type cells (G) and is also abundant in the vacuole of Catmut cells (H). M, mitochondria; N, nucleus; P, peroxisomes; V, vacuole. The bar represents 0.5 µm.

Degradation of aggregates is reduced in dnm1, pex11 and atg11 cells

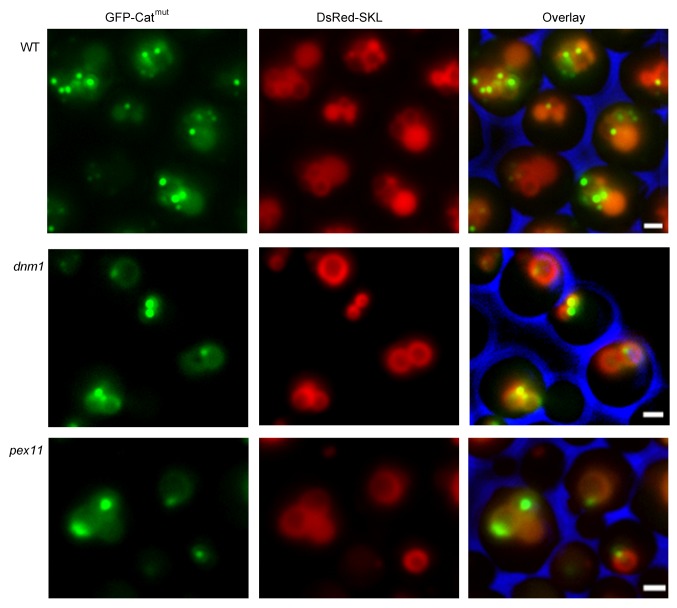

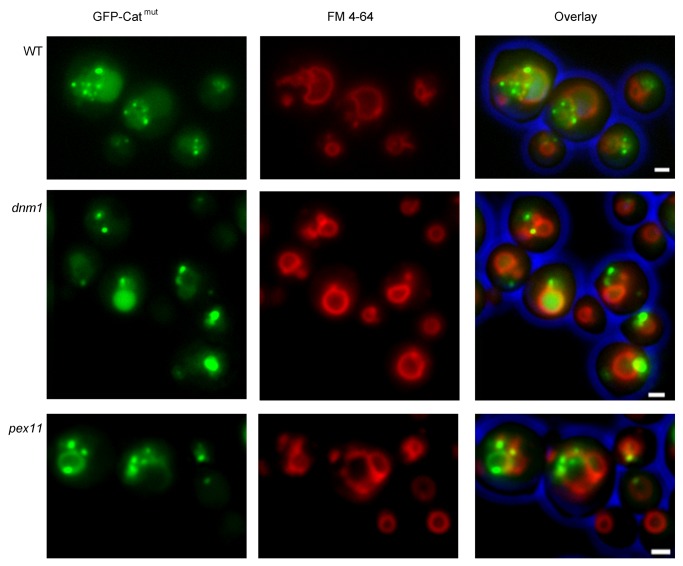

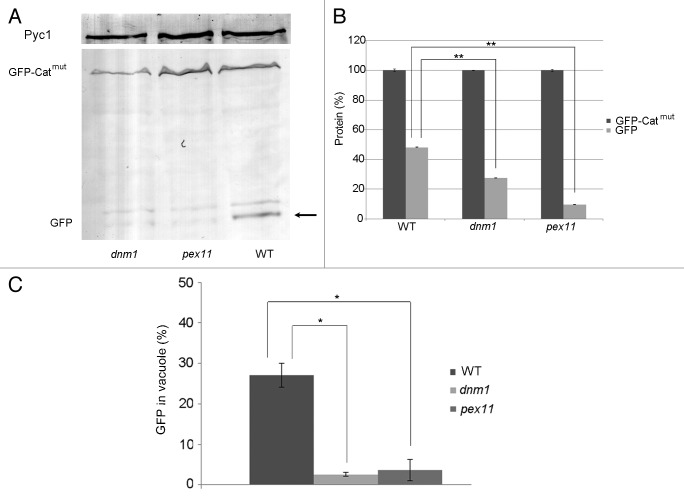

Clearly, the separation of small aggregate-containing peroxisomes is different from the fission events that participate in normal peroxisome proliferation in wild-type cells. Therefore, we analyzed if this fission process depends on Dnm1 and Pex11.19,20 To this end, corresponding deletion stains were constructed that produced Catmut N-terminally fused to GFP (GFP-Catmut) to fluorescently mark the protein aggregates. Fluorescence microscopy analysis of cells also producing the DsRed-SKL peroxisomal matrix marker protein revealed that small green fluorescent spots were present in peroxisomes of both mutant strains, as well as in the wild-type control (Fig. 5). To analyze the possible presence of GFP-Catmut in the vacuole, the red vacuolar marker FM 4–64 was used instead of DsRed-SKL (Fig. 6). Fluorescence microscopy analysis confirmed that green fluorescence was observed only infrequently in vacuoles of dnm1 and pex11 cells relative to the wild-type control (Fig. 6). Western blot analysis using crude extracts of these cells confirmed reduced cleavage of GFP-Catmut relative to that in the wild-type cells producing GFP-Catmut (Fig. 7). The reduced degradation of the aggregates also affected growth of the strains as lower growth yields on methanol were observed in both dnm1 and pex11 cells for the strains producing Catmut (Fig. 2A).

Figure 5. Visualization of catalase protein aggregates. H. polymorpha wild-type, dnm1 and pex11 cells, producing DsRed-SKL and GFP-Catmut, were grown on methanol for 16 h. The peroxisomes contained GFP spots in the peroxisomal lumen, which represent the protein aggregates.

Figure 6. Visualization of catalase protein aggregates. Identical experiment as shown in Figure 5, using wild-type, dnm1 and pex11 cells, producing GFP-Catmut stained with the vacuolar marker dye FM 4–64. GFP fluorescence was frequently observed in the vacuoles of wild-type cells. GFP fluorescence was also observed in the vacuoles of the dnm1 and pex11 cells, albeit at reduced numbers compared with the wild-type control. The bar represents 1 µm.

Figure 7. Autophagic degradation of GFP-Catmut is reduced in pex11 and dnm1 cells. (A) Western blot analysis using crude extracts of cells described in Figure 5, decorated with anti-GFP antibodies. All strains contain both the full-length GFP-Catmut protein together with GFP (arrow), due to cleavage of the fusion protein. Pyruvate carboxylase (Pyc1) was used as a loading control. (B) Quantification of the levels of GFP-Catmut and GFP protein of the blots shown in (A). The level of full-length GFP-Catmut is set to 100%. The bar represents the SEM (**p < 0.01). (C) Quantification of GFP fluorescence in the vacuole. The percentage of cells containing GFP fluorescence in the vacuole was calculated for wild-type, dnm1 and pex11 cells containing PAOXGFP-Catmut. Per strain 2 samples of each 100 cells were counted The bar represents the SEM (*p < 0.05).

To strengthen the observation that Dnm1 and Pex11 are indeed required for the separation of the small aggregate-containing peroxisomes, we also performed electron microscopy analysis of dnm1 atg1 and pex11 atg1 double-mutant cells producing Catmut. As evident from Figure 3D, these cells harbor large peroxisomes that contain protein aggregates.

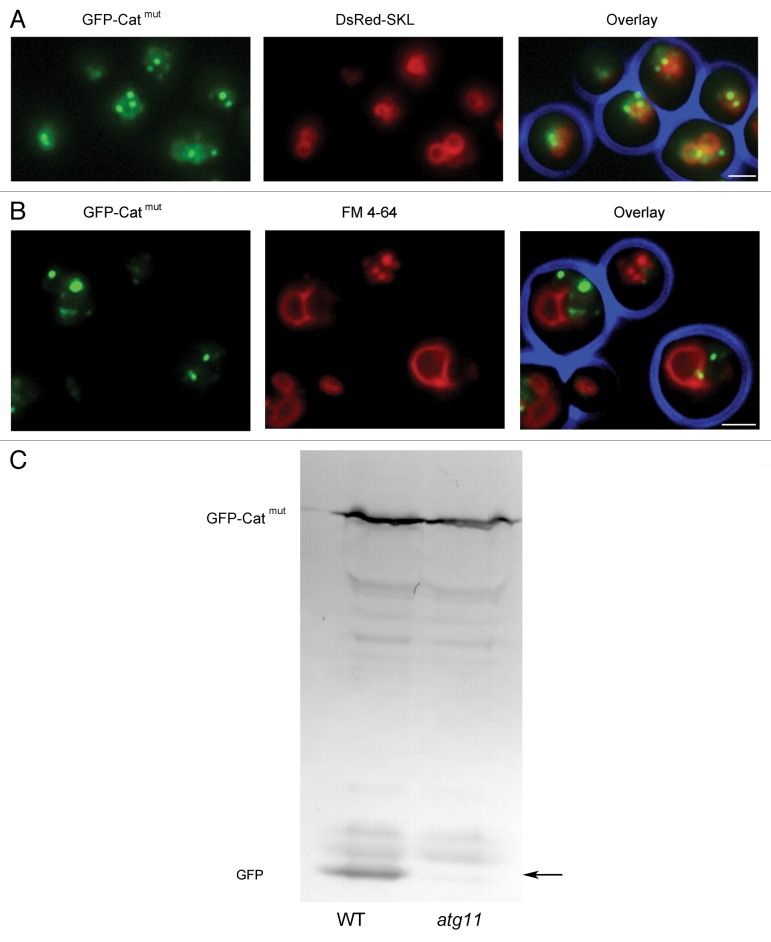

Degradation of the aggregates was also reduced upon deletion of ATG11, a gene involved in selective peroxisome degradation. In atg11 cells producing GFP-Catmut numerous green spots were observed (Fig. 8A). However, vacuoles did not accumulate GFP as observed in the wild-type background (compare Fig. 6 and Fig. 8B). The block in autophagic degradation was furthermore evident from western blot analysis of these cells showing that cleavage of GFP from the GFP-Catmut fusion protein was strongly reduced (Fig. 8C).

Figure 8. Autophagic degradation of GFP-Catmut is reduced in atg11 cells. (A) In H. polymorpha atg11 cells producing DsRed-SKL and GFP-Catmut and grown on methanol for 16 h, most GFP-Catmut spots colocalize with the peroxisomal matrix marker DsRed-SKL. Some of the green spots do not colocalize with DsRed-SKL. Most likely this is the result of the asymmetric peroxisome fission process, resulting in the formation of small aggregate-containing peroxisomes that contain no or very little DsRed-SKL. (B) Vacuolar staining of atg11 GFP-Catmut cells with FM 4–64 dye. GFP fluorescence in the vacuoles is reduced in atg11 cells relative to the wild-type control (see Fig. 6). The bar represents 1 µm. (C) Western blots decorated with anti-GFP antibodies fail to demonstrate the GFP cleavage product (arrow) in atg11 cells producing GFP-Catmut.

Discussion

Protein aggregates are harmful to cells and different machineries participate in the removal of these structures from various cellular compartments. However, so far nothing was known about the fate of protein aggregates in the peroxisomal matrix. In this study we present evidence that the presence of protein aggregates in the peroxisomal matrix of H. polymorpha affects cell performance and results in enhanced oxidative stress (Fig. 2). In order to remove these aggregates from their lumen, peroxisomes undergo asymmetric fission, yielding small organelles harboring these aggregates, which are degraded by pexophagy. The associated enhanced ROS levels may be related to toxicity of the catalase protein aggregates, which could affect the organelle’s redox homeostasis. The increased ROS levels may enhance expression of the endogenous wild-type catalase gene, which is still present in the strains, explaining the higher catalase activity observed in the cells producing the enzymatically inactive Catmut.

Previous data show that pharmacological activation of macroautophagy contributes to a decrease in aggregate-prone protein toxicity, such as that seen with mutant SNCA/α-synuclein and HTT/huntingtin in cultured cells.25 Autophagy also plays a role in the degradation of misfolded proteins, accumulated in the endoplasmic reticulum.26 Recent studies indicate that aberrant organelles may also be subject to autophagic degradation.27 Hence, autophagy of protein aggregates or cell organelles is very important to liberate eukaryotic cells of toxic and unwanted components.

Similar to mitochondria, peroxisomes are major sites of ROS production. Oxidative damage can result in protein unfolding and subsequent aggregate formation. Also, other environmental conditions (e.g., heat shock) are likely to induce the formation of peroxisomal protein aggregates. Although peroxisomes contain a Lon protease, which displays chaperone and proteolytic activity, the capacity of this enzyme may be insufficient under certain conditions or when high levels of aggregation-prone proteins are produced. Indeed, we recently showed that the production of a mutant variant of peroxisomal catalase resulted in the formation of large protein aggregates in peroxisomes.13 Also, we demonstrated that the absence of the peroxisomal Lon protease in yeast and filamentous fungi9 results in the appearance of peroxisomal protein aggregates.12 Hence, combining these data with our current findings, peroxisomal proteostasis involves the concerted action of a chaperone/protease protein (Lon) for soluble proteins together with autophagy for degradation of aggregates. This resembles the situation in the eukaryotic cytosol, where molecular chaperones (e.g., Hsp70) together with the ubiquitin-proteasome system and selective autophagy of aggregates (aggrephagy) combat protein aggregate formation.28

Peroxisome fission is the major mode of peroxisome multiplication in yeast.17,20 So far, this process was considered to be solely required to generate sufficient organelles to harbor proper levels of peroxisomal enzymes to fulfill metabolic needs. We now show that peroxisomal fission is also important for peroxisome degradation by pexophagy. First, we show that H. polymorpha mutants (dnm1, pex11) defective in peroxisome fission show a major reduction in glucose-induced pexophagy. Similarly, S. cerevisiae dnm1 vps1 cells, which are defective in peroxisome fission, show reduced glucose-induced pexophagy. Second, we show that H. polymorpha fission mutants display strongly reduced constitutive pexophagy. Hence, pexophagy required peroxisome multiplication. Possibly, this is a mode to prevent the degradation of the total peroxisome population within one cell, which would make the cell peroxisome deficient. Indeed, in cells containing one peroxisome (in dnm1, pex11 cells and mpp1 cells)19,20,23 peroxisomes are not degraded. The residual pexophagy that is observed in dnm1 and pex11 mutants most likely is confined to the few cells containing more than one peroxisome.

An alternative explanation for the observation that the very large peroxisomes in dnm1 or pex11 mutant cells are not degraded is that these organelles are too large to be enclosed within autophagosomes. Interestingly, studies in Pichia pastoris indicate that indeed the components of the autophagy machinery required for pexophagy differ for small and large organelles. Whereas degradation of small peroxisomes only requires the core components of the autophagy machinery (i.e., without pexophagy-specific Atg proteins), degradation of medium-sized organelles requires Atg26, and large peroxisomes also need Atg11. Hence, the additional components required for the larger organelles may be considered as an adaptation of the autophagy machinery.29 In this explanation these adaptations, however, may not be sufficient to degrade the giant peroxisomes in H. polymorpha dnm1 and pex11 cells.

For the removal of impaired regions of mitochondrial networks in mammalian cells, organelle fragmentation caused by fission separates polarized and depolarized daughter organelles, followed by selective autophagy of the depolarized ones.15,16 In this model, mitochondrial fission is an important process in keeping the cellular mitochondrial population healthy.30 However, whether this model is also true for yeast mitochondria is still debated. For S. cerevisiae, data have been presented that mitophagy induced by nitrogen starvation31 or Mdm38 dysfunction32 depends on the function of Dnm1, a protein that is involved in mitochondrial fission. Mendl and colleagues, however, suggest that there is no direct correlation between mitochondrial fission and mitophagy,33 based on studies using mutant Dnm1 variants and rapamycin induction. As is clear from the above, different modes of mitophagy induction have been used in these studies, which may in part explain the virtually conflicting data.

Peroxisomes containing protein aggregates may also be considered as impaired cell organelles. In line with the model proposed for mammalian mitochondria, we observed that upon peroxisome fission aberrant, aggregate-containing daughter organelles are degraded. It is tempting to speculate that these organelles are specifically degraded because they contain protein aggregates. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that under the conditions studied the autophagy machinery preferentially degrades smaller organelles, regardless of their aberrant nature.29 However, previous studies in which glucose-induced pexophagy was studied in wild-type H. polymorpha clearly indicate that under those conditions the larger peroxisomes are preferentially degraded.34

This fission/degradation machinery is very effective as judged from the observation that aggregate-induced peroxisome fission is not paralleled by an increase in average peroxisome numbers in wild-type cells, a phenomenon reinforced by the rapid accumulation of aggregate-containing autophagic bodies in cells incubated in the presence of PMSF. As such, it stresses the important role of autophagy in cellular housekeeping processes.

Materials and Methods

Organisms and growth

The Hansenula polymorpha strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Cells were grown at 37°C using either YPD (1% yeast extract, 1% peptone, 1% glucose) or mineral medium.37 For analysis of peroxisome fission, cells were precultivated using mineral medium containing 0.25% ammonium sulfate and 0.5% glucose as sole nitrogen and carbon sources, respectively. Exponential cultures were subsequently shifted to media containing 0.5% methanol or a mixture of 0.05% glycerol and 0.5% methanol as carbon sources. To induce pexophagy, cells were precultivated in mineral medium containing 0.5% methanol and shifted to medium containing 0.5% glucose. When required, media were supplemented with 30 µg/ml leucine or appropriate antibiotics. For cloning purposes, Escherichia coli DH5α was used as host for propagation of plasmids using Luria broth supplemented with appropriate antibiotics (100 µg/ml) and grown at 37°C.

Table 1.H. polymorpha strains used in this study.

| Strains | Characteristics | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type |

NCYC 495 leu1.1 |

35 |

| Catmut |

Strain containing pHIPX9-CATmut |

This study |

| PAOX GFP-Catmut |

Strain with pSEM031 |

This study |

| PMP47-GFP |

WT PPMP47 PMP47-GFP |

36 |

| PMP47-GFP Catmut |

WT PPMP47 PMP47-GFP strain with pHIPX9- CATmut |

This study |

| DsRed-SKL GFP-Catmut |

WT PAOX.DsRed-SKL integrated with pSEM031 |

This study |

|

atg1 |

ATG1 deletion strain leu 1.1 |

24 |

|

atg1 Catmut |

atg1 with pHIPX9-CATmut |

This study |

|

atg1 PMP47-GFP |

atg1 PPMP47-PMP47-GFP |

This study |

|

atg1 PMP47-GFP Catmut |

atg1 PPMP47-PMP47-GFP with pHIPX9- CATmut |

This study |

|

dnm1 |

DNM1 deletion strain, hygromycin |

This study |

|

pex11 |

PEX11 deletion strain, hygromycin |

This study |

|

dnm1 PMP47-GFP |

dnm1 PPMP47-PMP47-GFP |

This study |

|

pex11 PMP47-GFP |

pex11 PPMP47-PMP47-GFP |

This study |

|

dnm1 PMP47-GFP Catmut |

DNM1 PPMP47-PMP47-GFP with pHIPX9- CATmut |

This study |

|

pex11 PMP47-GFP Catmut |

PEX11 PPMP47-PMP47-GFP with pHIPX9- CATmut |

This study |

|

dnm1atg1 PPMP47-PMP47-GFP Catmut |

dnm1 atg1 PPMP47-PMP47-GFP with pHIPX9-CATmut |

This study |

|

pex11atg1 PPMP47-PMP47-GFP Catmut |

pex11 atg1 PPMP47-PMP47-GFP with pHIPX9-CATmut |

This study |

|

atg11 |

NCYC 495 ATG11 deletion, URA3, leu1.1 |

21 |

|

atg11 GFP-Catmut |

atg11 strain with pSEM031 |

This study |

|

atg11 DsRed-SKL GFP- Catmut |

atg11 PAOX.DsRed-SKL strain with pSEM031 |

This study |

|

dnm1 |

DNM1 deletion strain, ura3 |

20 |

|

dnm1 DsRed-SKL GFP- Catmut |

dnm1 PAOX.DsRed-SKL strain with pSEM031 |

This study |

|

dnm1 GFP-Catmut |

dnm1 strain with pSEM031 |

This study |

|

pex11 |

PEX11 deletion leu1.1 |

19 |

|

pex11 DsRed-SKL GFP- Catmut |

pex11 PAOX.DsRed-SKL strain with pSEM031 |

This study |

| pex11 GFP-Catmut | pex11 with pSEM031 | This study |

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains used in this study are listed in Table 2. Cells were grown at 30°C. Upon precultivation in mineral medium containing 0.25% ammonium sulfate and 0.5% glucose, cells were shifted to mineral medium containing 0.1% oleate, 0.05% Tween 80, and 0.05% yeast extract. Whenever necessary, media were supplemented with leucine (30 mg/l), histidine (20 mg/l), uracil (30 mg/l) or lysine (30 mg/l). For peroxisome degradation analysis, exponential oleate cultures were shifted to SD(-N) medium containing 0.17% yeast nitrogen base without nitrogen and amino acids (YNB) (Boom, Y0626) supplemented with 2% glucose.

Table 2.S. cerevisiae strains used in this study.

| Strains | Characteristics | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| BY4742 WT GFP-SKL |

BY4742 WT.URA3 PMET25 GFP.SKL |

22 |

| BY4742 dnm1 GFP-SKL |

BY4742 DNM1 deletion URA3 PMET25 GFP.SKL |

22 |

| BY4742 vps1 GFP-SKL |

BY4742 vps1 deletion URA3 PMET25 GFP.SKL |

22 |

| BY4742 dnm1 vps1 GFP-SKL |

DNM1 VPS1 double deletion HIS3URA3 PMET25 GFP.SKL |

22 |

| atg1 | ATG1 deletion strain HIS3 URA3 LEU2 | 46 |

Molecular and biochemical techniques

Plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 3. Standard recombinant DNA techniques and transformation of H. polymorpha was performed by electroporation as described previously.40

Table 3. Plasmids used in this study.

| Plasmid | Description | Source/Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| pHIPX9–CATmut |

pHIPX9 containing PCATCAT Y348G (point mutation in the heme binding site of catalase) and the PTS1–SKL at the C terminus, kanR |

13 |

| pHipZ4-DsRed-T1-SKL |

Plasmid containing PAOX DsRed –SKL, ampR, zeoR |

20 |

| pDONOR-221 |

Standard gateway vector |

Invitrogen |

| pDEST-R4-R3-NAT |

pDEST-R4-R3-containing nourseothricin marker, ampR |

20 |

| pENTR-23-TAMO |

pENTR-23 containing terminator of amine oxidase, kanR |

20 |

| pHIPZ-PMP47-mGFP |

pHIPZ containing-PMP47-mGFP under the control of PPMP47, zeoR, ampR |

36 |

| pENTR-L4R1-PAOX-GFP |

pDONOR-P4-P1 containing GFP under the control of PAOX, kanR |

38 |

| pENTR-221-Catmut |

pDONOR-221 containing Catmut, kanR |

This study |

| pSEM031 |

pDEST-R4-R3-containing PAOX GFP-Catmut-TAMO, nourseothricin marker, ampR |

This study |

| pDONR-P4-P1R |

Standard Gateway vector |

Invitrogen |

| pDONR-P2-R3 |

Standard Gateway vector |

Invitrogen |

| pENTR-221-HPH |

pENTR-221 containing hygromycin marker, kanR |

39 |

| pENTR DNM1 5′ |

pDONR4 P4–1R containing 5′ region of DNM1, kanR |

20 |

| pENTR DNM1 3′ |

pDONR P2-P3 containing 3′ region of DNM1, kanR |

20 |

| pSEM122 |

pDESTR4-R3 containing DNM1 deletion cassette with hygromycin marker, ampR |

This study |

| pKVK106 |

pDONR4 P4–1R containing 5′-region of PEX11, kanR |

19 |

| pKVK107 |

pDONR P2-P3 containing 3′-region of PEX11, kanR |

19 |

| pDEST PEX11-HPH | pDESTR4-R3 containing PEX11 deletion cassette with hygromycin marker, ampR | This study |

Cell extracts of trichloroacetic acid treated cells were prepared for sodium dodecyl sulfate PAGE as detailed previously.41 Equal volumes of the cultures were loaded per lane, followed by western blot analysis.42 Blots were probed with rabbit polyclonal antiserum against AO, thiolase or pyruvate carboxylase (Pyc1) or mouse monoclonal antiserum against GFP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-9996). Blots were scanned by using a densitometer (Biorad GS-710) and quantified using ImageJ (version 1.37); 3 measurements were performed on each band of 3 individual blots per sample.

Preparation of crude cell extracts43 and catalase activity measurements44 were performed as described previously. Protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay.

Construction of gateway plasmids

For the construction of plasmid pSEM031, Gateway Technology (Invitrogen, 12537.023) was used. A PCR fragment of 1587 bp of pHIPX9-Catmut with Gateway sites was obtained by primers Cat Fw B1 (GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTCGATGTCAAACCCCCCTGTTTTCAC) and Cat Rv B2 (GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTCGATTAAAGTTTGGATGGAGAAG) on pHIPX9-CATmut plasmid. The resulting PCR fragment was cloned into the standard Gateway vector pDONOR-221 to obtain pENTR-221- Catmut. Recombination of the entry vectors pENTR-L4R1-PAOX GFP, pENTR-221- Catmut and pENTR-23-TAMO and the destination vector pDEST-R4-R3, resulted in plasmid pSEM031 (pDEST vector containing the PAOXGFP-Catmut-TAMO cassette). For stable integration of the plasmid into the H. polymorpha genome, the plasmid was linearized with StuI in the PAOX region and transformed into H. polymorpha wild-type, atg11, dnm1 and pex11 strains, which produce DsRed-SKL as a peroxisomal matrix marker. The plasmid pHipZ4-DsRed-T1-SKL was linearized with KpnI and randomly integrated in the genome of the above H. polymorpha strains.

The pDEST Pex11-HPH deletion cassette was obtained by the Gateway recombination of plasmids pKVK106, pKVK107, pENTR-221-HPH and pDEST-R4-R3. From the resultant plasmid, a 2.6 kb fragment of the pex11 deletion cassette was amplified by PCR with the primers (PEX11-del3.1/PEX11-del3.2)19 and integrated in H. polymorpha wild-type and atg1 PMP47-GFP cells. Similarly, the plasmid pSEM122 was made by the recombination of plasmids pENTR DNM1 5′, pENTR DNM1 3′, pENTR-221-HPH and pDEST-R4-R3. A 2.4 kb fragment of the DNM1 deletion cassette was amplified by PCR with the primers DNM1 del. fwd (GCAGGACATTGTGACCAATACC) and DNM1 del. Rev (CCTCATATAGCAGCTCGTCGAA). The amplified fragment was integrated in H. polymorpha wild-type and atg1 PMP47-GFP cells.

Fluorescence and electron microscopy

Wide-field images were made using a Zeiss Axioscope fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Sliedrecht, The Netherlands). Images were taken using a Princeton Instruments 1300Y digital camera. The GFP signal was visualized by using a 470/40 nm bandpass excitation filter, a 495 nm dichromatic mirror and a 525/50 nm bandpass emission filter. DsRed fluorescence was visualized with a 546/12 nm bandpass excitation filter, a 560 nm dichromatic mirror and a 575/640 nm bandpass emission filter. For vacuolar staining, 1 ml of cell culture was supplemented with 1 µl FM 4–64 (Invitrogen, T-13320), incubated for 60 min at 37°C and analyzed. For electron microscopy, whole cells were fixed in 1.5% KMnO4 for 20 min, dehydrated in a graded ethanol series and embedded in Epon 812 (Serva, 21045). For immunocytochemistry cells were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer pH 7.2 for 60 min and embedded in Unicryl (Aurion, 14660). Immunolabeling was performed on ultrathin sections using specific polyclonal antisera and gold conjugated goat anti-rabbit antiserum (Aurion, 815.011).45

ROS measurements

Samples of methanol-grown H. polymorpha cells were harvested after 16 and 40 h of cultivation. Approximately 5 × 106 cells were collected by centrifugation and subsequently resuspended in 250 µl of phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4, containing 20 µM dihydrorhodamine (Invitrogen, D-632). After 30 min incubation at room temperature in the dark, cells were washed with PBS and resuspended in 500 µl of PBS for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis using a BD FACS Aria TM II.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tim van Zutphen, Dr. C.Q. Scheckhuber, Dr. J.A.K.W. Kiel, Dr. Anita Kram and A.M. Krikken for skillful assistance in various parts of this study.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AO

alcohol oxidase

- FACS

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FM 4-64

N-(3-triethylammoniumpropyl)-4-(6-(4 (diethylamino)phenyl)hexatrienyl) pyridinium dibromide

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PMSF

phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride

- Pyc1

pyruvate carboxylase-1

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SEM

standard error of the mean

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/autophagy/article/24543

References

- 1.Lozy F, Karantza V. Autophagy and cancer cell metabolism. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2012;23:395–401. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todde V, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ. Autophagy: principles and significance in health and disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1792:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuervo AM. Autophagy: in sickness and in health. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:70–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris H, Rubinsztein DC. Control of autophagy as a therapy for neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8:108–17. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2011.200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartl FU, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in protein folding and proteostasis. Nature. 2011;475:324–32. doi: 10.1038/nature10317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ciechanover A. Intracellular protein degradation: from a vague idea through the lysosome and the ubiquitin-proteasome system and onto human diseases and drug targeting. Medicina (B Aires) 2010;70:105–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Z, Klionsky DJ. An overview of the molecular mechanism of autophagy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;335:1–32. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-00302-8_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirsch C, Jarosch E, Sommer T, Wolf DH. Endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation--one model fits all? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695:215–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bartoszewska M, Williams C, Kikhney A, Opaliński L, van Roermund CW, de Boer R, et al. Peroxisomal proteostasis involves a Lon family protein that functions as protease and chaperone. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:27380–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.381566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiel JAKW. Autophagy in unicellular eukaryotes. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365:819–30. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellu AR, Kiel JAKW. Selective degradation of peroxisomes in yeasts. Microsc Res Tech. 2003;61:161–70. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aksam EB, Koek A, Kiel JAKW, Jourdan S, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ. A peroxisomal lon protease and peroxisome degradation by autophagy play key roles in vitality of Hansenula polymorpha cells. Autophagy. 2007;3:96–105. doi: 10.4161/auto.3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams C, Bener Aksam E, Gunkel K, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ. The relevance of the non-canonical PTS1 of peroxisomal catalase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1133–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manivannan S, Scheckhuber CQ, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ. The impact of peroxisomes on cellular aging and death. Front Oncol. 2012;2:50. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2012.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Twig G, Elorza A, Molina AJ, Mohamed H, Wikstrom JD, Walzer G, et al. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J. 2008;27:433–46. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Twig G, Hyde B, Shirihai OS. Mitochondrial fusion, fission and autophagy as a quality control axis: the bioenergetic view. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:1092–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Motley AM, Hettema EH. Yeast peroxisomes multiply by growth and division. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:399–410. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonekamp NA, Sampaio P, de Abreu FV, Lüers GH, Schrader M. Transient complex interactions of mammalian peroxisomes without exchange of matrix or membrane marker proteins. Traffic. 2012;13:960–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2012.01356.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krikken AM, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ. Hansenula polymorpha pex11 cells are affected in peroxisome retention. FEBS J. 2009;276:1429–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagotu S, Saraya R, Otzen M, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ. Peroxisome proliferation in Hansenula polymorpha requires Dnm1p which mediates fission but not de novo formation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:760–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monastyrska I, Kiel JAKW, Krikken AM, Komduur JA, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ. The Hansenula polymorpha ATG25 gene encodes a novel coiled-coil protein that is required for macropexophagy. Autophagy. 2005;1:92–100. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.2.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuravi K, Nagotu S, Krikken AM, Sjollema K, Deckers M, Erdmann R, et al. Dynamin-related proteins Vps1p and Dnm1p control peroxisome abundance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3994–4001. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leao-Helder AN, Krikken AM, van der Klei IJ, Kiel JAKW, Veenhuis M. Transcriptional down-regulation of peroxisome numbers affects selective peroxisome degradation in Hansenula polymorpha. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:40749–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komduur JA, Veenhuis M, Kiel JAKW. The Hansenula polymorpha PDD7 gene is essential for macropexophagy and microautophagy. FEMS Yeast Res. 2003;3:27–34. doi: 10.1016/s1567-1356(02)00135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ravikumar B, Vacher C, Berger Z, Davies JE, Luo S, Oroz LG, et al. Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nat Genet. 2004;36:585–95. doi: 10.1038/ng1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimura S, Maruyama J, Kikuma T, Arioka M, Kitamoto K. Autophagy delivers misfolded secretory proteins accumulated in endoplasmic reticulum to vacuoles in the filamentous fungus Aspergillus oryzae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;406:464–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.02.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Zutphen T, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ. Damaged peroxisomes are subject to rapid autophagic degradation in the yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Autophagy. 2011;7:863–72. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.8.15697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lamark T, Johansen T. Aggrephagy: selective disposal of protein aggregates by macroautophagy. Int J Cell Biol. 2012;2012:736905. doi: 10.1155/2012/736905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nazarko TY, Farré JC, Subramani S. Peroxisome size provides insights into the function of autophagy-related proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:3828–39. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-03-0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Twig G, Shirihai OS. The interplay between mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:1939–51. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanki T, Wang K, Baba M, Bartholomew CR, Lynch-Day MA, Du Z, et al. A genomic screen for yeast mutants defective in selective mitochondria autophagy. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:4730–8. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-03-0225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nowikovsky K, Reipert S, Devenish RJ, Schweyen RJ. Mdm38 protein depletion causes loss of mitochondrial K+/H+ exchange activity, osmotic swelling and mitophagy. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1647–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendl N, Occhipinti A, Müller M, Wild P, Dikic I, Reichert AS. Mitophagy in yeast is independent of mitochondrial fission and requires the stress response gene WHI2. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:1339–50. doi: 10.1242/jcs.076406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Veenhuis M, Douma A, Harder W, Osumi M. Degradation and turnover of peroxisomes in the yeast Hansenula polymorpha induced by selective inactivation of peroxisomal enzymes. Arch Microbiol. 1983;134:193–203. doi: 10.1007/BF00407757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sudbery PE, Gleeson MA, Veale RA, Ledeboer AM, Zoetmulder MC. Hansenula polymorpha as a novel yeast system for the expression of heterologous genes. Biochem Soc Trans. 1988;16:1081–3. doi: 10.1042/bst0161081a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cepińska MN, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ, Nagotu S. Peroxisome fission is associated with reorganization of specific membrane proteins. Traffic. 2011;12:925–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Dijken JP, Otto R, Harder W. Growth of Hansenula polymorpha in a methanol-limited chemostat. Physiological responses due to the involvement of methanol oxidase as a key enzyme in methanol metabolism. Arch Microbiol. 1976;111:137–44. doi: 10.1007/BF00446560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saraya R, Krikken AM, Kiel JAKW, Baerends RJ, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ. Novel genetic tools for Hansenula polymorpha. FEMS Yeast Res. 2012;12:271–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2011.00772.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saraya R, Krikken AM, Veenhuis M, van der Klei IJ. Peroxisome reintroduction in Hansenula polymorpha requires Pex25 and Rho1. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:885–900. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 40.Faber KN, Haima P, Harder W, Veenhuis M, Ab G. Highly-efficient electrotransformation of the yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Curr Genet. 1994;25:305–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00351482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baerends RJ, Faber KN, Kram AM, Kiel JAKW, van der Klei IJ, Veenhuis M. A stretch of positively charged amino acids at the N terminus of Hansenula polymorpha Pex3p is involved in incorporation of the protein into the peroxisomal membrane. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9986–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.14.9986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Klei IJ, Harder W, Veenhuis M. Selective inactivation of alcohol oxidase in two peroxisome-deficient mutants of the yeast Hansenula polymorpha. Yeast. 1991;7:813–21. doi: 10.1002/yea.320070806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luck H. Catalase. In Methods of Enzymatic Analysis (Edited by H. Bergmeyer). New York Academic Press 1963; 885-894. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waterham HR, Titorenko VI, Haima P, Cregg JM, Harder W, Veenhuis M. The Hansenula polymorpha PER1 gene is essential for peroxisome biogenesis and encodes a peroxisomal matrix protein with both carboxy- and amino-terminal targeting signals. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:737–49. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.3.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Straub M, Bredschneider M, Thumm M. AUT3, a serine/threonine kinase gene, is essential for autophagocytosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3875–83. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.3875-3883.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]