Abstract

Deficiency of SERPINA1/AAT [serpin peptidase inhibitor, clade A (α-1 antiproteinase, antitrypsin), member 1/α 1-antitrypsin] results in polymerization and aggregation of mutant SERPINA1 molecules in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes, triggering liver injury. SERPINA1 deficiency is the most common genetic cause of hepatic disease in children and is frequently responsible for chronic liver disease in adults. Liver transplantation is currently the only available treatment for the severe form of the disease. We found that liver-directed gene transfer of transcription factor EB (TFEB), a master regulator of autophagy and lysosomal biogenesis, results in marked reduction of toxic mutant SERPINA1 polymer, apoptosis and fibrosis in the liver of a mouse model of SERPINA1 deficiency. TFEB-mediated correction of hepatic disease is dependent upon increased degradation of SERPINA1 polymer in autolysosomes and decreased expression of SERPINA1 monomer. In conclusion, TFEB gene transfer is a novel strategy for treatment of liver disease in SERPINA1 deficiency. Moreover, this study suggests that TFEB-mediated cellular clearance may have broad applications for therapy of human disorders due to intracellular accumulation of toxic proteins.

Keywords: TFEB, autophagy, gene transfer, lysosome, α-1-antitrypsin deficiency

TFEB is a master gene regulating the autophagy-lysosome pathway. TFEB colocalizes with the master growth regulator MTOR complex 1 (MTORC1) on the lysosomal membrane, and, upon dephosphorylation, is activated and migrates into the nucleus where it acts as a transcription factor. Induction of autophagy and lysosomal biogenesis by TFEB gene transfer has already shown efficacy for rescue of pathological lysosomal storage in lysosomal storage diseases. In this study, we investigated TFEB gene transfer for a nonlysosomal disorder, α 1-antitrypsin deficiency, a common genetic cause of liver disease. SERPINA1 is synthesized in the liver and released into the plasma, where it is the most abundant circulating protease inhibitor. Approximately 90% of patients with SERPINA1 deficiency are homozygotes for a missense mutation (lysine for glutamate at amino acid position 342) that alters protein folding. As a consequence of the folding defect, mutant SERPINA1 molecules polymerize and aggregate in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of hepatocytes, forming large intrahepatocytic globules that are the pathological hallmark of the disease. We hypothesized that liver-directed gene transfer of TFEB can induce autophagy and lysosomal biogenesis in hepatocytes and can result in clearance of toxic SERPINA1 polymers. To achieve efficient in vivo liver-directed TFEB gene transfer, we used nonintegrating helper-dependent adenoviral (HDAd) vectors that are devoid of all viral coding sequences, have a large cloning capacity, and result in long-term transgene expression without chronic toxicity. The efficacy of hepatic TFEB gene transfer was evaluated in the PiZ mouse model, a transgenic mouse that expresses the mutant human SERPINA1 gene under the control of its endogenous regulatory elements and recapitulates the features of human liver disease. Livers of PiZ mice injected with HDAd-TFEB showed a sustained reduction of intrahepatocytic globules and SERPINA1 polymers. Importantly, they also exhibited reduced hepatic fibrosis and apoptosis that are key features of the liver disease. Livers of HDAd-TFEB injected mice showed higher levels of LAMP1, enhanced SQSTM1/p62 degradation, increased LC3-I, and translocation of mutant SERPINA1 inclusions into autolysosomes. Despite evidence of autophagy increase, LC3-II levels were apparently unchanged and the overall number of autophagosomes decreased upon TFEB expression, thus suggesting that TFEB gene transfer stimulates fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes and accelerates autophagy flux (Fig. 1).

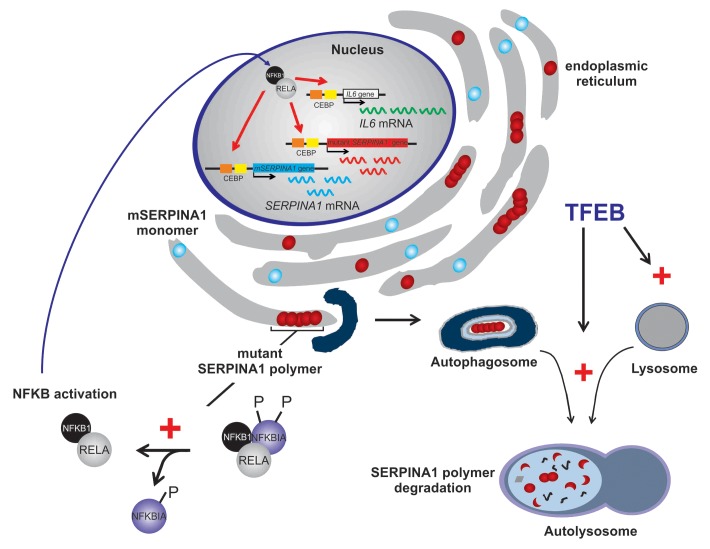

Figure 1. TFEB gene transfer interrupts the pathogenic vicious cycle of SERPINA1 deficiency. In livers of PiZ mice, mutant SERPINA1 accumulation activates the NFKB pathway that aggravates the burden of intracellular mutant SERPINA1. NFKB-dependent increase of IL6 and NFKB activation enhance mutant, human SERPINA1 and mouse SERPINA1 expression. TFEB gene transfer increases disposal of SERPINA1 polymer in autolysosomes by increasing lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy flux. Therefore, TFEB interrupts the positive feedback loop that results in increased NFKB activation, IL6, and SERPINA1 expression.

Electron microscopy (EM) analysis and immunolabeling for SERPINA1 on liver thin sections showed reduced and smaller SERPINA1-positive inclusions in the cytoplasm of mice injected with HDAd-TFEB. In sharp contrast to control mice, immuno-EM revealed significant amounts of mutant SERPINA1 within autolysosomes, thus showing that TFEB gene transfer enhances degradation of insoluble mutant SERPINA1 in these compartments. In vitro studies in cells deleted for Atg7 confirmed that degradation of mutant SERPINA1 is abrogated in the absence of functioning autophagy.

Previous studies have shown mitochondrial autophagy and injury in the liver of both mice and humans with SERPINA1 deficiency. However, it has been questioned whether the autophagic response that resulted in nonspecific removal of normally functioning mitochondria, or retention of mutant SERPINA1 in the ER is itself responsible for mitochondrial dysfunction. Our study provides evidence that the latter is more likely responsible for mitochondrial dysfunction, because TFEB-mediated increase of liver autophagy in PiZ mice resulted in normalization of mitochondrial morphology and number, and increased levels of the mitochondria-specific proteins citrate synthase and COX4.

In addition to decreased mutant SERPINA1 polymer, upon TFEB gene transfer, we also detected a significant reduction of SERPINA1 mRNA and monomer. This must involve a different mechanism from the increased degradation of SERPINA1 polymer in the autolysosomes. In the transgenic PiZ mice, both wild-type mouse SERPINA1 and mutant human SERPINA1 are expressed, and the latter retains the cis-acting elements regulating its expression (Fig. 1). Reduced SERPINA1 expression was hypothesized to be secondary to increased SERPINA1 polymer degradation that resulted in decreased activation of NFKB and decreased IL6. Both activated NFKB and IL6 promote SERPINA1 transcription. Indeed, we found that TFEB-mediated increase of SERPINA1 polymer degradation interrupts a vicious cycle that raises the burden of intracellular mutant SERPINA1 resulting in ER stress, NFKB activation, and increased SERPINA1 transcription (Fig. 1).

For up to six months of TFEB expression, PiZ mice appeared in general good health and were indistinguishable from control groups, and no evidence of hepatic toxicity was detected. More in-depth toxicity studies in both small and large animals are needed to investigate the safety of long-term TFEB expression. Nevertheless, results of the present study illustrate the potential of TFEB gene transfer, or possibly of pharmacological approaches that result in its activation and nuclear translocation, for therapy of liver disease caused by hepatotoxic mutant SERPINA1.

In conclusion, liver-directed TFEB gene transfer resulted in correction of hepatic disease by increased SERPINA1 polymer degradation mediated by enhancement of autophagy flux. Hepatic correction was also driven by decreased hepatic NFKB activation and IL6 that drive SERPINA1 gene expression. The results of this study suggest that TFEB gene transfer may be effective for treatment of a wide spectrum of human disorders due to intracellular accumulation of toxic proteins.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/autophagy/article/24469