Abstract

Purpose: A number of potential determinants of medication non-adherence have been described so far. However, the heterogenic quality of existing publications poses the need for the use of a rigorous methodology in building a list of such determinants. The purpose of this study was a systematic review of current research on determinants of patient adherence on the basis of a recently agreed European consensus taxonomy and terminology.

Methods: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, IPA, and PsycINFO were systematically searched for systematic reviews published between 2000/01/01 and 2009/12/31 that provided determinants on non-adherence to medication. The searches were limited to reviews having adherence to medication prescribed by health professionals for outpatient as a major topic.

Results: Fifty-one reviews were included in this review, covering 19 different disease categories. In these reviews, exclusively assessing non-adherence to chronic therapies, 771 individual factor items were identified, of which most were determinants of implementation, and only 47—determinants of persistence with medication. Factors with an unambiguous effect on adherence were further grouped into 8 clusters of socio-economic-related factors, 6 of healthcare team- and system-related factors, 6 of condition-related factors, 6 of therapy-related factors, and 14 of patient-related factors. The lack of standardized definitions and use of poor measurement methods resulted in many inconsistencies.

Conclusions: This study provides clear evidence that medication non-adherence is affected by multiple determinants. Therefore, the prediction of non-adherence of individual patients is difficult, and suitable measurement and multifaceted interventions may be the most effective answer toward unsatisfactory adherence. The limited number of publications assessing determinants of persistence with medication, and lack of those providing determinants of adherence to short-term treatment identify areas for future research.

Keywords: medication adherence, patient compliance, persistence, concordance, medication use, determinants of adherence

Introduction

Enormous progress in the fields of both medicine, and pharmacology has taken place in the last century and led to a completely new paradigm of treatment. Contrary to the past, in which most treatments were only available in hospitals, effective remedies are available now in ambulatory settings. At the same time, the demographic changes that happen to both developed and developing countries, make chronic conditions even more prevalent. All this makes the most modern treatments dependent on patient self-management. Surprisingly often, evidence based treatments fail to succeed because of the human factor known for a few decades as patient non-adherence.

Currently, sound theoretical foundations for adherence-enhancing interventions are lacking (van Dulmen et al., 2007). Therefore, the development of interventions to enhance patient adherence to medication, and maintain long term persistence, requires at least an understanding of the determinants of patient non-adherence to prescribed therapies. This is especially important when the determinants are modifiable risk factors, which, once identified, can then be targeted for beneficial changes.

The published literature identifies hundreds of determinants of non-adherence. Unfortunately, serious drawbacks of the methodology used by numerous studies demand that this list be revised. In particular, many studies do not indicate the relative importance of the 3 identified components of patient adherence: initiation, implementation, and discontinuation. For example, the WHO recommends that determinants be classified in 5 dimensions (Sabate, 2003): socio-economic factors, healthcare team and system-related factors, condition-related factors, therapy-related factors, and patient-related factors, but provides little or no closure in respect to outcome, and in particular, to the stage of adherence process. Moreover, little information exists on the determinants of short-term adherence for acute diseases vs. long-term adherence for chronic diseases.

The objective of this study was to identify and classify the determinants of non-adherence to short-term and long-term treatments for different clinical sectors and population segments. In order to obtain this goal, a retrospective systematic review of the literature was performed, wherein we have adopted the method of reviewing reviews. In order to design a comprehensive, yet evidence-based list of determinants of patient adherence for use in both practical and clinical settings, as well as for theoretical purposes to inform adherence-enhancing interventions, a rigorous taxonomy and terminology of adherence was used, the basis of which was set recently in a form of a European consensus (Vrijens et al., 2012). According to this terminology, adherence to medications is defined as the process by which patients take their medications as prescribed. Adherence has three components: initiation, implementation, and discontinuation, of which initiation is defined as the moment at which the patient takes the first dose of a prescribed medication; the implementation of the dosing regimen, being the extent to which a patient's actual dosing corresponds to the prescribed dosing regimen from initiation until the last dose taken; and discontinuation, being the end of therapy, when the next dose to be taken is omitted and no more doses are taken thereafter (Vrijens et al., 2012).

This study is part of a larger project on patient medication adherence funded by the European Commission called the “ABC (Ascertaining Barriers for Compliance) Project” (http://www.abcproject.eu). The overall goal of the ABC project was to produce evidence-based policy recommendations for improving patient adherence and by so doing to promote safer, more effective and cost-effective medicines use in Europe.

Methods

As the number of publications with the keyword “patient compliance” (text word), and “patient compliance” as MESH major term is so high, (close to 50,000 hits, and 16,000 in PubMed by 2009/12/31, respectively), only recent systematic reviews are included in this search; More precisely the inclusion criteria comprised systematic reviews in the English language, published between 2000/01/01 and 2009/12/31, having adherence to medication intended to be taken in outpatient settings prescribed by health professionals, as a major topic of publication, if determinants of adherence are provided.

MEDLINE (through PubMed), EMBASE, CINAHL, the Cochrane Library, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts (IPA), and PsycINFO were searched for relevant publications. In order to increase search coverage, a number of possible synonyms for medication adherence (i.e., patient compliance, concordance, patient dropouts, treatment refusal, and directly observed therapy), in combination with several synonyms of determinants were used for keywords. The detailed search strategies for all databases are provided in Appendix 1. For the other databases, the search strategies were adapted accordingly.

Papers were excluded for the following reasons: (1) Studies that primarily focused on adherence-enhancing interventions. (2) Studies that were not systematic reviews. (3) Studies that assessed adherence to non-medication intervention (e.g., vaccination). (4) Double citations. (5) Determinants of adherence to medication not provided. No paper was excluded on the grounds of quality.

Eligibility assessment of title and abstract was performed independently in an unblended standardized manner by two reviewers (PK, PL). If at least one reviewer coded a review as potentially eligible, the review was included for full-text review. The full texts of potentially eligible reviews were retrieved and reviewed by both reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and a final decision was reached between the two reviewers.

A structured data collection sheet was developed to extract data from each review. All available relevant data was extracted from the reviews; no additional information was sought from the authors. The following paragraphs describe which data was extracted.

Determinants of adherence to medication

A range of determinants were extracted based on the source publications. These were further categorized according to their effect on adherence to medication using an adherence determinant matrix. Relevant dimensions included:

Treatment duration: long- vs. short-term treatment;

Components of adherence to medication: implementation of the dosing regimen (defined as the extent to which a patient's actual dosing corresponds to the prescribed dosing regimen) vs. persistence (defined as the length of time between initiation and the last dose which immediately precedes discontinuation) (Vrijens et al., 2012). Determinants were categorized under implementation unless original review wording clearly addressed persistence.

Dimensions of adherence: these were socio-economic factors, healthcare team- and system-related factors, condition-related factors, therapy-related factors, and patient-related factors. In this was original WHO report description followed (Sabate, 2003), with a modification: demographic variables were included under patient-related, instead of socio-economic related factors.

Direction of effect: determinants were classified according to their positive, negative, neutral, or not defined effect on adherence.

Other data extracted from the reviews included scope of the review (medical condition, class of drugs, etc.), studied population, and databases searched by the authors.

Results

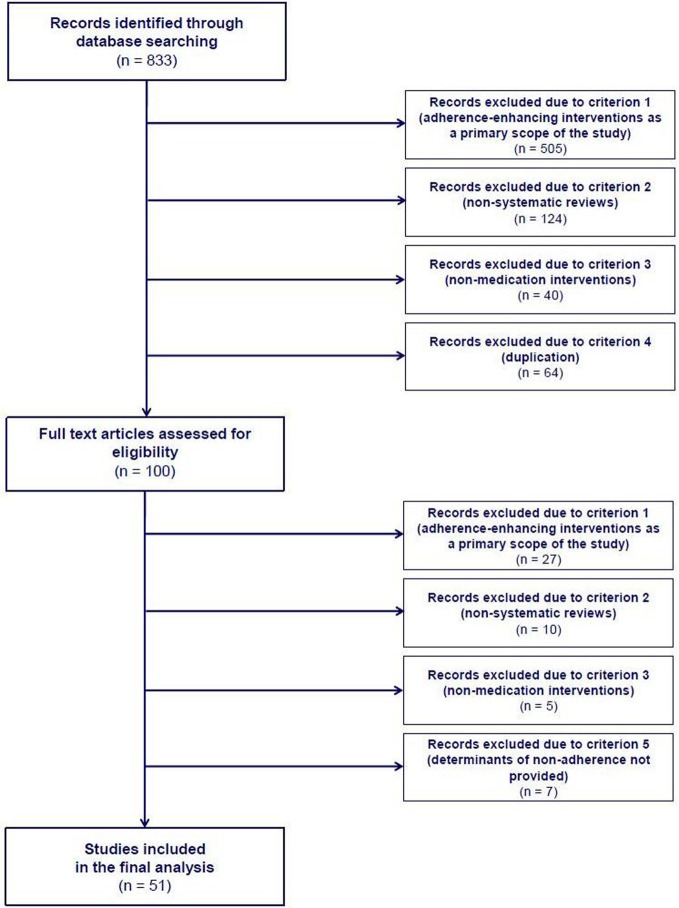

In this systematic literature review, 51 systematic reviews were found to contain determinants of adherence to medication. An overview of the review process and reasons for exclusion at various steps within it are detailed in Figure 1. Individual study characteristics are listed in Appendix 2. Great variety was seen in both the start year of the literature searches performed within the source reviews, starting back from as early as 1948, or as late as 2000, as well as the period covered by the search, varying from 5 to over 50 years. Most of the studies accepted broad definitions of adherence, making no distinction between intentional, and unintentional non-adherence; only in 4 studies were clear operational definitions provided (Iskedjian et al., 2002; Lacro et al., 2002; Wetzels et al., 2004; Bao et al., 2009; Parienti et al., 2009). The majority of the studies were systematic reviews. However, 8 reviews (DiMatteo et al., 2000, 2007; Iskedjian et al., 2002; DiMatteo, 2004a,b; Gonzalez et al., 2008; Bao et al., 2009; Parienti et al., 2009) were also enriched with meta-analyses, and provided calculations of the effect on adherence of factors from several dimensions:

Socio-economic factors: practical social support (OR 3.60, 95%CI 2.55 - 5.19), emotional support (OR 1.83, 95%CI 1.27, 2.66], unidimensional social support (OR 2.35, 95%CI 1.76–3.03], family cohesiveness (OR 3.03, 95%CI 1.99–4.52], being married (OR 1.27, 95%CI 1.12–1.43), as well as living with someone (for adults, OR 1.38, 95%CI 1.04–1.83) increased the odds of adherence, whereas family conflict decreased these odds (OR 2.35, 95%CI 1.08, 5.71) (DiMatteo, 2004a)

Condition-related factors: patients rated poorer in health by their physicians were more adherent to treatment (OR 1.76, 95%CI 1.13 - 2.77) (DiMatteo et al., 2007)

Therapy-related factors: the average adherence rate for QD dosing was significantly higher than for BID dosing in hypertension (92.7% vs. 87.1%) (Iskedjian et al., 2002) and antiretroviral therapy (+2.9%, 95%CI 1.0-4.8%) (Parienti et al., 2009), in hypertension adherence was also significantly higher for QD dosing vs. >QD dosing (91.4 vs. 83.2%, respectively) (Iskedjian et al., 2002). In methadone treatment, persistence was higher with higher daily methadone doses (> or =60 mg vs. <60 mg/day, OR: 1.74, 95%CI 1.43-2.11), as well as with flexible-dose strategies vs. fixed-dose strategies (OR: 1.72, 95%CI 1.41–2.11) (Bao et al., 2009)

Patient-related factors: an extensive review found older age, female gender, higher income, and more education to have small yet positive effects on adherence (DiMatteo, 2004b). A belief that the medical condition in question was a threat because of its severity increased the odds of adherence (OR 2.45, 95%CI 1.91–3.16) (DiMatteo et al., 2007). Depression was significantly associated with non-adherence across various conditions (OR 3.03, 95%CI 1.96–4.89) (DiMatteo et al., 2000), and in particular, in diabetes (z 9.97, P 0.0001) (Gonzalez et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection process.

Within our selected reviews, the most common focus of the studies were miscellaneous diseases (10 reviews) (DiMatteo et al., 2000, 2007; Claxton et al., 2001; Vermeire et al., 2001; Connor et al., 2004; DiMatteo, 2004a,b; Vik et al., 2004; Chia et al., 2006; Kruk and Schwalbe, 2006), followed by HIV (8 reviews) (Fogarty et al., 2002; Mills et al., 2006; Malta et al., 2008; Vreeman et al., 2008; Lovejoy and Suhr, 2009; Parienti et al., 2009; Ramos, 2009; Reisner et al., 2009), and psychiatric conditions (8 reviews) (Oehl et al., 2000; Lacro et al., 2002; Pampallona et al., 2002; Nosé et al., 2003; Santarlasci and Messori, 2003; Charach and Gajaria, 2008; Julius et al., 2009; Lanouette et al., 2009) (Table 1). Disease categories were broad (19 different diseases); reviews exclusively reported patients with chronic diseases.

Table 1.

Fields covered by the selected reviews.

| Field | No. of reviews |

|---|---|

| Miscellaneous diseases | 10 |

| HIV | 8 |

| Psychiatric conditions | 8 |

| Diabetes | 3 |

| Hypertension | 3 |

| Cancer | 2 |

| End stage renal disease | 2 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 2 |

| Osteoporosis | 2 |

| Transplantations | 2 |

| Tuberculosis | 2 |

| Cystic fibrosis | 1 |

| Skin diseases | 1 |

| Glaucoma | 1 |

| Heart failure | 1 |

| Malaria | 1 |

| Opioid dependence | 1 |

| Non-malignant chronic pain | 1 |

Close to half of the reviews (25 out of 51) did not specify the age group of patients covered by the review. Of the rest, most dealt with adults (11 reviews, Table 2).

Table 2.

Patient groups covered by the selected reviews.

| Patient group | No. |

|---|---|

| Not specified | 25 |

| Adults | 11 |

| Children + adults | 8 |

| Children | 4 |

| Elderly | 2 |

| Youth | 1 |

Determinants of adherence to medication

As many as 771 individual factor items associated with long-term treatment were extracted from the reviewed literature: Despite the broad range of the fields covered with these publications, no publication primarily focusing on short-term therapies was identified, nor were any individual determinants of patient adherence to short-term treatment. The vast majority of individual factor items were determinants of implementation, and only 47 were found to be determinants of persistence with medication. Only three reviews addressed the initiation component of adherence, although no corresponding determinants were provided (Vermeire et al., 2001; Vik et al., 2004; Costello et al., 2008).

For 64 individual factor items, no unambiguous information concerning their effect on adherence to medication could be found in the source publication. The remaining factors were grouped to form 400 individual determinants: 143 with a positive, 155 with negative, and 102 with neutral effect on adherence. In cases where the source publications provided two “mirror” versions of the same factor, e.g., family support and lack of family support,, these were recategorized as the factor with a negative effect on adherence, in this case, lack of family support. The determinants were further clustered according to the modified WHO 5 dimension of adherence (see Methods for details). The results are presented in Tables 3–7 as socio-economic-related factors (8 clusters), healthcare team- and system-related factors (6 clusters), condition-related factors (6 clusters), therapy-related factors (6 clusters), and patient-related factors (14 clusters).

Table 3.

Socio-economic factors affecting adherence.

| Factors having | ||

|---|---|---|

| Negative effect on adherence | Positive effect on adherence | Neutral effect on adherence |

| FAMILY SUPPORT | ||

| FAMILY/CAREGIVERS FACTORS | ||

|

|

|

| SOCIAL SUPPORT | ||

|

|

|

| SOCIAL STIGMA OF A DISEASE | ||

|

|

|

| COSTS OF DRUGS AND/OR TREATMENT | ||

| PRESCRIPTION COVERAGE | ||

|

||

| SOCIOECONOMIC STATUS | ||

|

||

| EMPLOYMENT STATUS | ||

|

||

Abbreviations

- TB

tuberculosis;

, determinant of persistence.

Table 7.

Patient-related factors affecting adherence.

| Factors having | ||

|---|---|---|

| Negative effect on adherence | Positive effect on adherence | Neutral effect on adherence |

| AGE | ||

|

|

|

| GENDER | ||

| MARITAL STATUS | ||

| EDUCATION | ||

| ETHNICITY | ||

| HOUSING | ||

|

||

| COGNITIVE FUNCTION | ||

| FORGETFULNESS AND REMINDERS | ||

| KNOWLEDGE | ||

|

||

| HEALTH BELIEFS | ||

|

|

|

| PSYCHOLOGICAL PROFILE | ||

|

|

|

| COMORBIDITIES AND PATIENT HISTORY | ||

|

|

|

| ALCOHOL OR SUBSTANCE ABUSE | ||

|

|

|

| PATIENT-RELATED BARRIERS TO COMPLIANCE | ||

Abbreviations

- HF

heart failure;

- MS

multiple sclerosis;

- TB

tuberculosis;

, determinant of persistence.

Discussion

In this systematic literature review, 51 systematic reviews concerning the determinants of adherence of medication were identified. Remarkably, a vast majority of the reviewed literature provided only determinants of implementation. In fact, many reviews lacked a clear definition of adherence, thus leaving the distinction between implementation and persistence open to interpretation. In the present study, these cases were arbitrarily reclassified under determinants of implementation, assuming that in most cases, authors were interested in the day-to-day execution of drug taking. The recently-agreed European consensus on taxonomy and terminology of adherence has made more precise reporting of research findings in the field of adherence to medication possible (Vrijens et al., 2012). However, in interpreting results of this study, one has to have in mind this limitation.

Many reviews reported a positive effect of family and social support on implementation, and a negative effect of the lack of such support (Table 3). The social stigma of a disease may also be responsible for non-adherence in a number of cases. Finally, economic factors such as unemployment, poverty, lack of, or inadequate medical/prescription coverage, as well as a high out-of-pocket cost of drugs may seriously contribute to non-adherence.

Although non-adherence has often been perceived as the fault of patients, and not of healthcare providers, there is evidence that healthcare system factors have an important impact on adherence (Table 4). Poor access to healthcare, poor drug supply, unclear information about drug administration, as well as poor follow-up and poor provider-patient communication and relationship may reduce the extent to which patients follow the treatment plan.

Table 4.

Healthcare team and system-related factors affecting adherence.

| Factors having | ||

|---|---|---|

| Negative effect on adherence | Positive effect on adherence | Neutral effect on adherence |

| BARRIERS TO HEALTHCARE | ||

|

||

| DRUG SUPPLY | ||

|

||

| PRESCRIPTION BY A SPECIALIST | ||

|

||

| INFORMATION ABOUT DRUG ADMINISTRATION | ||

|

||

| HEALTHCARE PROVIDER-PATIENT COMMUNICATION AND RELATIONSHIP | ||

|

|

|

| FOLLOW-UP | ||

|

|

|

Abbreviations

- GP

general practitioner;

- TB

tuberculosis;

, determinant of persistence.

Adherence is also related to condition. Asymptomatic nature of the disease, as well as clinical improvement reduce patient motivation to take the drugs as prescribed, whereas disease severity has a positive effect on adherence (Table 5). Patients are also less happy to take the prescribed medication properly in both chronic and psychiatric conditions.

Table 5.

Condition-related factors affecting adherence.

| Factors having | ||

|---|---|---|

| Negative effect on adherence | Positive effect on adherence | Neutral effect on adherence |

| PRESENCE OF SYMPTOMS | ||

| DISEASE SEVERITY | ||

| CLINICAL IMPROVEMENT | ||

| PSYCHIATRIC CONDITION | ||

|

|

|

| CERTAIN DIAGNOSES/INDICATIONS | ||

|

||

| DURATION OF THE DISEASE | ||

|

||

Abbreviations

- ART

antiretroviral therapy;

- ESRD

end stage renal disease;

- TB

tuberculosis;

, determinant of persistence.

If treatment is patient unfriendly – e.g., due to frequent dosing, high number of prescribed medications, longer duration of treatment, drug formulation or taste of low acceptance, or the presence of adverse effects, the likelihood of patient adherence drops (Table 6). Certain drug classes are better adhered to compared with others.

Table 6.

Therapy-related factors affecting adherence.

| Factors having | ||

|---|---|---|

| Negative effect on adherence | Positive effect on adherence | Neutral effect on adherence |

| ADVERSE EFFECTS | ||

|

||

| PATIENT FRIENDLINESS OF THE REGIMEN | ||

|

|

|

| DRUG EFFECTIVENESS | ||

| DURATION OF THE TREATMENT | ||

|

|

|

| DRUG TYPE | ||

|

||

| WELL ORGANISED TREATMENT | ||

Abbreviations

- ACEi

angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors;

- aRB

angiotensin II receptor antagonists;

- BBs

beta-blockers;

- CCBs

calcium channel blockers;

- DOT

directly observed therapy;

, determinant of persistence.

Not surprisingly, many patient-related factors were found to be reported as having an inconsistent impact on adherence in terms of implementation (Table 7). This was particularly true for demographic factors: whereas younger age was reported to have a negative impact on adherence, and older age a positive one, many reviews found no relationship between age and implementation of treatment regimen (Oehl et al., 2000; Vermeire et al., 2001; Lacro et al., 2002; DiMatteo, 2004b; Vik et al., 2004; Olthoff et al., 2005; Hodari et al., 2006; Hirsch-Moverman et al., 2008; Reisner et al., 2009; Ruddy et al., 2009). The male gender was reported to have a negative impact in some reviews (Nosé et al., 2003; Olthoff et al., 2005; Schmid et al., 2009), and the female gender a positive one (Oehl et al., 2000; Pampallona et al., 2002; Chia et al., 2006; Munro et al., 2007; Julius et al., 2009). However, gender was found irrelevant for adherence in many cases (Vermeire et al., 2001; Fogarty et al., 2002; Lacro et al., 2002; DiMatteo, 2004b; Vik et al., 2004; Van Der Wal et al., 2005; Charach and Gajaria, 2008; Hirsch-Moverman et al., 2008; Karamanidou et al., 2008; Broekmans et al., 2009; Lanouette et al., 2009; Reisner et al., 2009), and male gender was found to have a contrary effect with posttransplant medications (Charach and Gajaria, 2008) and with psychostymulants in children with ADHD (Jindal et al., 2003). The same was true for marital status, with some reviews indicating that those married tended to have better adherence than those being single or divorced, education level, with better adherence demonstrated by patients with higher levels of education, and ethnicity, with higher adherence in Caucasians. Patient attitudes and believes in favor of diagnosis, health recommendations and self-efficacy were closely related to adherence, as was knowledge of the disease and consequences of poor adherence. On the other hand, many beliefs were found to be possible barriers for strict adherence. Poorer adherence can be expected with either drug or alcohol dependence. Finally, comorbidities and patient history had an inconsistent effect on adherence, with the exception of psychiatric conditions, which was frequently reported to be connected with the lower rates of adherence (Claxton et al., 2001; Jindal et al., 2003; Nosé et al., 2003; Hodari et al., 2006; Mills et al., 2006; Munro et al., 2007; Charach and Gajaria, 2008; Karamanidou et al., 2008; Malta et al., 2008; Reisner et al., 2009; Schmid et al., 2009).

Only few determinants of persistence were identified. Socio-economic factors with a negative impact on persistence included high costs of drugs and treatment (Gold et al., 2006; Munro et al., 2007; Costello et al., 2008), poverty (Costello et al., 2008), lower socioeconomic status (Charach and Gajaria, 2008), or inadequate medical/prescription coverage (Charach and Gajaria, 2008; Costello et al., 2008). Several healthcare system-related factors also had a negative effect on persistence, such as lack of providers/caregiver availability (Charach and Gajaria, 2008), poor healthcare provider-patient relationship (Charach and Gajaria, 2008), or poor follow-up by providers (Gold et al., 2006). Asymptomatic nature of disease (Gold et al., 2006), as well as clinical improvement, disappearance of symptoms, feeling better/cured (Oehl et al., 2000; Munro et al., 2007), the presence of adverse effects (Gold et al., 2006; Charach and Gajaria, 2008; Costello et al., 2008; Brandes et al., 2009) and complexity of the regimen (Gold et al., 2006; Munro et al., 2007) all decreased patient motivation to persist with treatment, as did high dosing frequency (Charach and Gajaria, 2008), doses during the day (Charach and Gajaria, 2008), and finally, drug ineffectiveness, objective or perceived (Munro et al., 2007; Charach and Gajaria, 2008; Costello et al., 2008). This findings are of special interest, as longer persistence is a primary goal for adherence-enhancing interventions. On the other hand, it is noteworthy that the vast majority of persistence determinants were also implementation determinants (see Tables 3–7).

Our findings are consistent with those of the other authors (Vermeire et al., 2001; DiMatteo, 2004b). However, the strength of this study is the rigorous methodology that we employed to classify literature search findings. A predefined set of criteria, and the use of well-defined terminology to describe the deviation of patients from prescribed treatment allowed a cohesive matrix of factors to be built that were determinants of either adherence or non-adherence. Bearing in mind that at least 200 factors have so far been suggested to play some role in determining adherence (Vermeire et al., 2001), the approach adopted in our study seems to move our understanding of adherence to medication forward. The clear distinction between implementation of the regimen (daily drug-taking) and persistence (continuity of treatment) allows the first, to the best of our knowledge, clear distinction of the determinants of these two components of adherence to medication to be made, thus providing a more detailed insight into the role of some determinants of the adherence process, compared with previous approaches (e.g., the WHO 5 dimensions).

Our analysis provides clear evidence that medication non-adherence is affected by multiple determinants, belonging to several different fields. Many of these factors are not modifiable, and none of them is a sole predictor of adherence. Moreover, some of these factors change with time and can appear at times either to be a cause, or a consequence, of patient non-adherence. Nevertheless, non-adherence should not be perceived as patients' fault only. To the contrary, social factors (such as social support, economic factors, etc.), healthcare-related factors (e.g., barriers to healthcare, and quality of provider-patient communication), condition characteristics, as well as therapy-related factors (such as patient friendliness of the therapy) play an important role in defining adherence.

Consequently, multifaceted interventions may be the most effective answer toward unsatisfactory adherence, and its consequences. In their review of reviews of effectiveness of adherence-enhancing interventions, van Dulmen et al. found effective interventions in each of four groups: technical, behavioral, educational and multi-faceted or complex interventions (van Dulmen et al., 2007). In their Cochrane review, Haynes et al. (Haynes et al., 2008) observed that most of the interventions that were effective for long-term care were complex, targeting multiple adherence determinants. We believe that evidence accumulated in this study may help in designing such effective interventions, and thus, be applied in both clinical practice and public health.

Bearing in mind the number of identified determinants and their inconsistent effect on adherence, prediction of non-adherence of individual patients is difficult if not impossible. In particular, the inconsistent effect of demographic variables on patient adherence explains partly why healthcare providers are ineffective in predicting adherence in their patients (Okeke et al., 2008). In fact, their prediction rate is no better than a coin toss (Mushlin and Appel, 1977). Neither age, gender, marital status, nor education proved to fully explain the variance in patient adherence across conditions and settings. Therefore, in order to reveal cases of non-adherence, validated tools (e.g., Morisky, or MARS questionnaires), and objective assessment methods (electronic monitoring widely accepted as a gold standard) are strongly advisable (Osterberg and Blaschke, 2005). In daily practice, relevant databases, such as electronic health records, and pharmacy fill records, may be effectively used for screening for non-adherence (Carroll et al., 2011; Grimes et al., 2013). On the other hand, adherence-enhancing interventions are worth considering to implement in daily clinical practice, to be used on a regular basis for every individual patients.

Finally, another strength of this systematic literature review is the identification of existing gaps in our understanding of adherence. Of note is that despite the broad inclusion criteria adopted for this search, no systematic review was identified which provides determinants of adherence with short-term treatments. Considering the high prevalence of non-adherence to short-term therapies, and especially, to antibiotics (Kardas et al., 2005; Vrijens et al., 2005), our findings identify this field as an important area for future research.

The major limitation of this study was connected with the data available within the source publications that were used for this review. Most did not provide any precise definition of adherence, nor any numeric values to describe the effect of the particular determinants on adherence (e.g., the effect size), thus making secondary analysis not manageable. The poor designs of many original studies on determinants of non-adherence could affect the conclusions of identified reviews, and indirectly, the results of this review.

The “review of reviews” methodology we employed in the present study proved to be a valuable tool for gathering relevant studies. However, despite the fact that the source reviews adopted different focuses, the certain level of overlap in primary studies they reviewed cannot be ruled out. Nevertheless, as the aim of the study was to build a comprehensive list of determinants, and not to perform a meta-analysis, this possible overlap was not a source of additional bias.

Finally, although our selection of the databases searched was only arbitral, it did correspond with the major goal, i.e., identification of publications describing determinants of adherence to medication. According to our experience, and knowledge of similar publications, broadening the scope of the databases included would not add much to the findings.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms Elzbieta Drozdz and Ms Malgorzata Zajac (Main Library of the Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland) for their helpful technical guidance on conducting literature searches. This study, as part of the ABC project, was funded by the European Commission Seventh Framework Programme (FP7 Theme Health, 2007-3.1-5, grant agreement number 223477).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/Pharmaceutical_Medicine_and_Outcomes_Research/10.3389/fphar.2013.00091/abstract

References

- Bao Y. P., Liu Z. M., Epstein D. H., Du C., Shi J., Lu L. (2009). A meta-analysis of retention in methadone maintenance by dose and dosing strategy. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 35, 28–33 10.1080/00952990802342899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramlage P., Hasford J. (2009). Blood pressure reduction, persistence and costs in the evaluation of antihypertensive drug treatment–a review. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 8, 18 10.1186/1475-2840-8-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes D. W., Callender T., Lathi E., O'Leary S. (2009). A review of disease-modifying therapies for MS: maximizing adherence and minimizing adverse events. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 25, 77–92 10.1185/03007990802569455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekmans S., Dobbels F., Milisen K., Morlion B., Vanderschueren S. (2009). Medication adherence in patients with chronic non-malignant pain: is there a problem. Eur. J. Pain 13, 115–123 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll N. M., Ellis J. L., Luckett C. F., Raebel M. A. (2011). Improving the validity of determining medication adherence from electronic health record medications orders. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 18, 717–720 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charach A., Gajaria A. (2008). Improving psychostimulant adherence in children with ADHD. Expert Rev. Neurother. 8, 1563–1571 10.1586/14737175.8.10.1563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia L. R., Schlenk E. A., Dunbar-Jacob J. (2006). Effect of personal and cultural beliefs on medication adherence in the elderly. Drugs Aging 23, 191–202 10.2165/00002512-200623030-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claxton A. J., Cramer J., Pierce C. (2001). A systematic review of the associations between dose regimens and medication compliance. Clin. Ther. 23, 1296–1310 10.1016/S0149-2918(01)80109-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor J., Rafter N., Rodgers A. (2004). Do fixed-dose combination pills or unit-of-use packaging improve adherence. A systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 82, 935–939 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello K., Kennedy P., Scanzillo J. (2008). Recognizing non-adherence in patients with multiple sclerosis and maintaining treatment adherence in the long term. Medscape J. Med. 10, 225 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer J. A. (2004). A systematic review of adherence with medications for diabetes. Diabetes Care 27, 1218–1224 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo M. R. (2004a). Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 23, 207–218 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo M. R. (2004b). Variations in patients' adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med. Care 42, 200–209 10.1097/01.mlr.0000114908.90348.f9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo M. R., Haskard K. B., Williams S. L. (2007). Health beliefs, disease severity, and patient adherence: a meta-analysis. Med. Care 45, 521–528 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318032937e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo M. R., Lepper H. S., Croghan T. W. (2000). Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch. Intern. Med. 160, 2101–2107 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty L., Roter D., Larson S., Burke J., Gillespie J., Levy R. (2002). Patient adherence to HIV medication regimens: a review of published and abstract reports. Patient Educ. Couns. 46, 93–108 10.1016/S0738-3991(01)00219-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold D. T., Alexander I. M., Ettinger M. P. (2006). How can osteoporosis patients benefit more from their therapy. Adherence issues with bisphosphonate therapy. Ann. Pharmacother. 40, 1143–1150 10.1345/aph.1G534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez J. S., Peyrot M., McCarl L. A., Collins E. M., Serpa L., Mimiaga M. J., et al. (2008). Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 31, 2398–2403 10.2337/dc08-1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes D. E., Andrade R. A., Niemeyer C. R., Grimes R. M. (2013). Measurement issues in using pharmacy records to calculate adherence to antiretroviral drugs. HIV Clin. Trials 14, 68–74 10.1310/hct1402-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes R. B., Ackloo E., Sahota N., McDonald H. P., Yao X. (2008). Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2:CD000011 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch-Moverman Y., Daftary A., Franks J., Colson P. W. (2008). Adherence to treatment for latent tuberculosis infection: systematic review of studies in the US and Canada. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 12, 1235–1254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodari K. T., Nanton J. R., Carroll C. L., Feldman S. R., Balkrishnan R. (2006). Adherence in dermatology: a review of the last 20 years. J. Dermatolog. Treat. 17, 136–142 10.1080/09546630600688515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iskedjian M., Einarson T. R., MacKeigan L. D., Shear N., Addis A., Mittmann N., et al. (2002). Relationship between daily dose frequency and adherence to antihypertensive pharmacotherapy: evidence from a meta-analysis. Clin. Ther. 24, 302–316 10.1016/S0149-2918(02)85026-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen R., Møldrup C., Christrup L., Sjøgren P. (2009). Patient-related barriers to cancer pain management: a systematic exploratory review. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 23, 190–208 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2008.00601.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jindal R. M., Joseph J. T., Morris M. C., Santella R. N., Baines L. S. (2003). Noncompliance after kidney transplantation: a systematic review. Transplant. Proc. 35, 2868–2872 10.1016/j.transproceed.2003.10.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julius R. J., Novitsky M. A., Dubin W. R. (2009). Medication adherence: a review of the literature and implications for clinical practice. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 15, 34–44 10.1097/01.pra.0000344917.43780.77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana S. Y., Frazier T. W., Drotar D. (2008). Preliminary quantitative investigation of predictors of treatment non-adherence in pediatric transplantation: a brief report. Pediatr. Transplant. 12, 656–660 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2007.00864.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamanidou C., Clatworthy J., Weinman J., Horne R. (2008). A systematic review of the prevalence and determinants of non-adherence to phosphate binding medication in patients with end-stage renal disease. BMC Nephrol. 9:2 10.1186/1471-2369-9-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kardas P., Devine S., Golembesky A., Roberts R. (2005). A systematic review and meta-analysis of misuse of antibiotic therapies in the community. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 26, 106–113 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2005.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk M. E., Schwalbe N. (2006). The relation between intermittent dosing and adherence: preliminary insights. Clin. Ther. 28, 1989–1995 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacro J. P., Dunn L. B., Dolder C. R., Leckband S. G., Jeste D. V. (2002). Prevalence of and risk factors for medication non-adherence in patients with schizophrenia: a comprehensive review of recent literature. J. Clin. Psychiatry 63, 892–909 10.4088/JCP.v63n1007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanouette N. M., Folsom D. P., Sciolla A., Jeste D. V. (2009). Psychotropic medication non-adherence among United States Latinos: a comprehensive literature review. Psychiatr. Serv. 60, 157–174 10.1176/appi.ps.60.2.157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee W. C., Balu S., Cobden D., Joshi A. V., Pashos C. L. (2006). Prevalence and economic consequences of medication adherence in diabetes: a systematic literature review. Manag. Care Interface 19, 31–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewiecki E. M. (2007). Long dosing intervals in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 23, 2617–2625 10.1185/030079907X233278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy T. I., Suhr J. A. (2009). The relationship between neuropsychological functioning and HAART adherence in HIV-positive adults: a systematic review. J. Behav. Med. 32, 389–405 10.1007/s10865-009-9212-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malta M., Strathdee S. A., Magnanini M. M. F., Bastos F. I. (2008). Adherence to antiretroviral therapy for human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome among drug users: a systematic review. Addiction 103, 1242–1257 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02269.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills E. J., Nachega J. B., Bangsberg D. R., Singh S., Rachlis B., Wu P., et al. (2006). Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 3:e438 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S. A., Lewin S. A., Smith H. J., Engel M. E., Fretheim A., Volmink J. (2007). Patient adherence to tuberculosis treatment: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med. 4:e238 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mushlin A. I., Appel F. A. (1977). Diagnosing potential noncompliance. Physicians' ability in a behavioral dimension of medical care. Arch. Intern. Med. 137, 318–321 10.1001/archinte.1977.03630150030010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosé M., Barbui C., Tansella M. (2003). How often do patients with psychosis fail to adhere to treatment programmes. A systematic review. Psychol. Med. 33, 1149–1160 10.1017/S0033291703008328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oehl M., Hummer M., Fleischhacker W. W. (2000). Compliance with antipsychotic treatment. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. Suppl. 407, 83–86 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.00016.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okeke C. O., Quigley H. A., Jampel H. D., Ying G. S., Plyler R. J., Jiang Y., et al. (2008). Adherence with topical glaucoma medication monitored electronically the travatan dosing aid study. Ophthalmology 116, 191–199 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olthoff C. M. G., Schouten J. S. A. G., van de Borne B. W., Webers C. A. B. (2005). Noncompliance with ocular hypotensive treatment in patients with glaucoma or ocular hypertension an evidence-based review. Ophthalmology 112, 953–961 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.12.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterberg L., Blaschke T. (2005). Adherence to medication. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 487–497 10.1056/NEJMra050100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pampallona S., Bollini P., Tibaldi G., Kupelnick B., Munizza C. (2002). Patient adherence in the treatment of depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 180, 104–109 10.1192/bjp.180.2.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parienti J. J., Bangsberg D. R., Verdon R., Gardner E. M. (2009). Better adherence with once-daily antiretroviral regimens: a meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48, 484–488 10.1086/596482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos J. T. (2009). Boosted protease inhibitors as a therapeutic option in the treatment of HIV-infected children. HIV Med. 10, 536–547 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00728.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisner S. L., Mimiaga M. J., Skeer M., Perkovich B., Johnson C. V., Safren S. A. (2009). A review of HIV antiretroviral adherence and intervention studies among HIV-infected youth. Top. HIV Med. 17, 14–25 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruddy K., Mayer E., Partridge A. (2009). Patient adherence and persistence with oral anticancer treatment. CA Cancer J. Clin. 59, 56–66 10.3322/caac.20004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabate E. (ed.). (2003). Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization [Google Scholar]

- Santarlasci B., Messori A. (2003). Clinical trial response and dropout rates with olanzapine versus risperidone. Ann. Pharmacother. 37, 556–563 10.1345/aph.1C291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid H., Hartmann B., Schiffl H. (2009). Adherence to prescribed oral medication in adult patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis: a critical review of the literature. Eur. J. Med. Res. 14, 185–190 10.1186/2047-783X-14-5-185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Wal M. H. L., Jaarsma T., Van Veldhuisen D. J. (2005). Non-compliance in patients with heart failure; How can we manage it. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 7, 5–17 10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dulmen S., Sluijs E., van Dijk L., de Ridder D., Heerdink R., Bensing J. (2007). Patient adherence to medical treatment: a review of reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 7:55 10.1186/1472-6963-7-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeire E., Hearnshaw H., Van Royen P., Denekens J. (2001). Patient adherence to treatment: three decades of research. A comprehensive review. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 26, 331–342 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2001.00363.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vik S. A., Maxwell C. J., Hogan D. B. (2004). Measurement, correlates, and health outcomes of medication adherence among seniors. Ann. Pharmacother. 38, 303–312 10.1345/aph.1D252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeman R. C., Wiehe S. E., Pearce E. C., Nyandiko W. M. (2008). A systematic review of pediatric adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low- and middle-income countries. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 27, 686–691 10.1097/INF.0b013e31816dd325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijens B., De Geest S., Hughes D. A., Kardas P., Demonceau J., Ruppar T., et al. (2012). A new taxonomy for describing and defining adherence to medications. Brit. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 73, 691–705 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04167.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijens B., Tousset E., Rode R., Bertz R., Mayer S., Urquhart J. (2005). Successful projection of the time course of drug concentration in plasma during a 1-year period from electronically compiled dosing-time data used as input to individually parameterized pharmacokinetic models. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 45, 461–467 10.1177/0091270004274433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner J. R., Toy E. L., Sacco P., Duh M. S. (2008). Costs, quality of life and treatment compliance associated with antibiotic therapies in patients with cystic fibrosis: a review of the literature. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 9, 751–766 10.1517/14656566.9.5.751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzels G. E., Nelemans P., Schouten J. S., Prins M. H. (2004). Facts and fiction of poor compliance as a cause of inadequate blood pressure control: a systematic review. J. Hypertens. 22, 1849–1855 10.1097/00004872-200410000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeung S., White N. J. (2005). How do patients use antimalarial drugs. A review of the evidence. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 10, 121–138 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01364.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.