Abstract

Background and objectives.

Acute respiratory infection (ARI) is among the most common, debilitating and expensive human illnesses. The purpose of this study was to assess ARI-related costs and determine if mindfulness meditation or exercise can add value.

Methods.

One hundred and fifty-four adults ≥50 years from Madison, WI for the 2009–10 cold/flu season were randomized to (i) wait-list control (ii) meditation or (iii) moderate intensity exercise. ARI-related costs were assessed through self-reported medication use, number of missed work days and medical visits. Costs per subject were based on cost of generic medications, missed work days ($126.20) and clinic visits ($78.70). Monte Carlo bootstrap methods evaluated reduced costs of ARI episodes.

Results.

The total cost per subject for the control group was $214 (95% CI: $105–$358), exercise $136 (95% CI: $64–$232) and meditation $65 (95% CI: $34–$104). The majority of cost savings was through a reduction in missed days of work. Exercise had the highest medication costs at $16.60 compared with $5.90 for meditation (P = 0.004) and $7.20 for control (P = 0.046). Combining these cost benefits with the improved outcomes in incidence, duration and severity seen with the Meditation or Exercise for Preventing Acute Respiratory Infection study, meditation and exercise add value for ARI. Compared with control, meditation had the greatest cost benefit. This savings is offset by the cost of the intervention ($450/subject) that would negate the short-term but perhaps not long-term savings.

Conclusions.

Meditation and exercise add value to ARI-associated health-related costs with improved outcomes. Further research is needed to confirm results and inform policies on adding value to medical spending.

Keywords. Complementary and alternative medicine, health economics, physical activity/exercise, prevention, upper respiratory infection/common cold, value.

Introduction

The cost of health care in America is at a breaking point. Despite having the most costly health care system in the world, the USA consistently underperforms on health outcomes relative to other countries.1 There is an active need to increase the value of medical spending to improve quality while reducing cost.2–4 Prevention has long been advocated, but the question remains whether investing resources in programs that encourage positive lifestyle behaviours, such as exercise and mindfulness, can result in cost savings and improved health.

Acute respiratory infection (ARI) is one of the most common, often debilitating and expensive human illnesses. ARI accounts for 20 million doctor visits in the USA with 40 million lost school and work days. The total cost of ARI in America is estimated at $40 billion for non-influenza ARI, making it one of the top 10 most expensive medical conditions.5 The most expensive health-related costs associated with ARI are missed days of work (‘work absenteeism’), followed by outpatient clinic visits and medications. Even a small reduction in the costs related to ARI evaluation, treatment and work absenteeism could have significant positive economic impact.

Data utilized for this cost-analysis study came from a randomized controlled trial (RCT) funded by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine at the National Institutes of Health, titled ‘Meditation or Exercise for Preventing Acute Respiratory Infection (MEPARI)’.6

The primary goal of the MEPARI study was to evaluate efficacy of meditation or exercise interventions in reducing ARI incidence, duration and severity. The aim of this secondary analysis was to assess costs to see if these interventions add value.

Methods

The MEPARI study enrolled adults ≥50 years from Madison, WI and randomized them to one of three parallel groups: (i) wait-list observation (control), (ii) an 8-week training in mindfulness meditation class (‘meditation’) or (iii) moderate intensity exercise class. Participants had no previous training in meditation, were not regular exercisers and reported ≥1 ARI episode per year. The MEPARI study showed reduced incidence, duration and severity of ARI with the results summarized in Table 2.6 The current study documented self-reported use of prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medications, number of and reason for medical clinic visits and number of missed days of school or work. Health care visits and missed work days were classified as either related or unrelated to ARI illness, both by having a score ≥2 on the Jackson ARI scale and by cross-checking against self-report Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptoms Survey-24 (WURSS-24)7 data. Data analysts were blinded to allocation. The original protocol was approved by the University of Wisconsin Health Sciences Institutional Review Board.

Table 2.

Results

| Exercise | Meditation | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 47 | n = 51 | n = 51 | |

| Primary Outcomes | |||

| Individuals with ARI illness (per cent of sample) (95% CI) | 17 (35%) | 21 (41%) | 28 (55%) |

| Number of ARI episodes | 26 | 27 | 40 |

| Mean global severity (95% CI) | 248 (77, 419) | 144 (62, 225) | 358 (221, 495) |

| Mean ARI illness days (95% CI) | 5.13 (2.64, 7.62) | 5.04 (2.25, 7.83) | 8.89 (5.76, 12.02) |

| Missed Days Work and Health Care Visits | |||

| Mean ARI-related missed days (95% CI) | 0.68 (0.1,1.2) | 0.31 (0.1,0.5) | 1.31 (0.5,2.1) |

| Mean ARI-related health care visits (95% CI) | 0.32 (0.14, 0.49) | 0.20 (0.07, 0.32) | 0.31 (0.12, 0.50) |

| Cost of OTC Medications and Antibiotics | |||

| Mean OTC Medication Cost | $6.10 (SD = 12.57) | $4.46 (SD = 9.95) | $4.89 (SD = 7.90) |

| Mean Antibiotic Cost | $10.46 (SD = 25.16) | $1.44 (SD = 4.88) | $2.29 (SD = 6.17) |

| Mean Combined Medication Cost (OTC + Abx) | $16.56 (SD = 32.55) | $5.90 (SD = 11.32) | $7.19 (SD = 11.26) |

| Cost Summary | |||

| Mean Cost per subject | $136 (SD = 293) | $65 (SD = 120) | $214 (SD = 416) |

Abx, Antibiotic.

Sample size

The sample size of n = 150 was based on power estimates for detecting significant difference in the primary efficacy endpoint of the RCT which contrasted (i) meditation versus control and (ii) exercise versus control. The trial was designed to demonstrate feasibility for collecting secondary outcome data and was understood to be somewhat underpowered for an economic evaluation.

Randomization

SAS software was used to generate 165 unique identification numbers in balanced blocks of three. Codes were concealed in consecutively numbered sealed envelopes and opened by the research coordinator after consent to indicate allocation.

Setting

This trial was coordinated by the University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine. Mindfulness meditation and exercise classes were offered through the University of Wisconsin Research Park, a multi-disciplinary, outpatient clinic with exercise facilities and space suitable for meditation training.

Recruitment and monitoring

Community-targeted recruitment methods included advertising in local media. Prospective participants were screened by phone by trained research coordinators and then met in person for entry into a two-part 2 week run-in/screening trial to assess adherence. Those completing run-in were eligible for consent and randomization into the main trial. For logistical reasons, the study had to be completed in 1 year and two cohorts were needed. The first began in September, the second in January. Participants were contacted biweekly via telephone by the study coordinator beginning post-intervention and continuing until study exit at the end of May.

Mindfulness meditation intervention

Mindfulness is one form of meditation that has been well studied in the medical literature. Mindfulness emphasizes the cultivation of attention on the present-moment with non-judgmental acceptance.8 By intentionally bringing one’s awareness to the present moment through attention to body sensations, thoughts and emotions, the mind is able to focus more clearly. This brings attention to what is actually happening instead of being caught in habitual and unconscious thought patterns that are often associated with stress and therefore may result in impaired immune function.9,10 Meditation is a tool used to cultivate this awareness. Customary to previous mindfulness studies, an 8-week training was implemented using the model originated by Jon Kabat-Zinn at the University of Massachusetts (mindfulness-based stress reduction, MBSR). It included weekly 2.5-hour meditation sessions facilitated by experienced instructors, along with encouragement for daily home practice.

Exercise

The moderate intensity exercise program was tailored to match the meditation program. It also lasted 8 weeks, was located in the same building and included 2.5 hours of weekly contact among the group and instructor. Participants were encouraged to practice 45 minutes of moderately intensive exercise daily using Borg’s perceived rating scale to encourage exertion that measured 12–16 on a 6–20 point scale.11 Experienced exercise physiotherapists led the groups. Weekly sessions included both didactic and practicum using stationary bikes, treadmills and other exercise machines. The didactic sessions focused on the health benefits of exercise and methods to encourage sustained habits. Exercise was used as a comparison group due to evidence suggesting that moderate exercise in this age group enhances immune function, reduces inflammation with a reduction in the incidence of infection.12 It differs from meditation in that it generally does not encourage a self-reflective process and is aimed at metabolic and physiological rather than cognitive and emotional domains.

Control

A wait-list control group served as a comparison group. They were monitored the same as those in the intervention and were offered meditation training free of charge, assistance enrolling in an exercise program, or $300 cash at the end of the study.

Outcome measures related to cost calculation

Value in health is defined by quality of health outcomes at reduced cost.4 To calculate societal costs of ARI, this study incorporates costs from lost work time, health care visits and medications. The three employed units of cost were (i) the mean cost of a day of lost work, (ii) the mean cost for a health care visit and (iii) the mean cost for medications used for an ARI.

ARI-related lost work days.

Study subjects comp leted surveys every 2 weeks for 14 weeks following the intervention. Participants self-reported the number of lost work days due to ARI through the following questions: ‘In the past 2 weeks, have you been unable to participate in any regular work or school activities because of your recent illness?’, ‘If Yes, how many days of work/school have you missed?’ and ‘Is the above related to an Acute Respiratory Infection (ARI)?’

The total number of ARI-related lost work days was multiplied by the daily wage for a worker in Wisconsin per the US Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics data. (http://www.bls.gov/oes/oes_dl.htm; accessed on 4 March 2013) A simulated wage distribution was calculated based on the 25th and 75th percentiles of the May 2010 Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates for all occupations in the state of Wisconsin. The resulting mean daily wage was $126.20 with a range from $84.60 to $191.90.

ARI-related health care visits.

Study respondents reported every 2 weeks for 14 weeks the number of clinic, urgent care or emergency department visits for ARI. The total number of ARI-related visits was multiplied by a per-visit cost based on representative data from the University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine (DFM) Data Warehouse. To determine per-ARI outpatient visit costs, we extracted visit data for any patient 50 years of age or older seen at a department of family medicine clinic in the past 2 years who had an ICD-9 code (460, 461.1, 461.2, 461.8, 461.9, 462, 463, 465.9, 466, 480.9, 487.1, 487.8, 490) for respiratory infection. The distribution of office visit level coding provided a representative sample of ARI-related visits. We then applied the Wisconsin Medicare-allowed reimbursement fee amount for 2011 to each visit based on level of office visit. The resulting mean office visit cost was $78.70 with a range of $39.90–$133.00.

OTC medications.

During biweekly phone visits, participants were asked to report all OTC medications for any acute illness taken during the previous 2-week period. For the purpose of this study, any OTC medication that would potentially alleviate ARI-related symptoms was included in the analysis. If a participant listed an appropriate OTC medication, we correlated it to a documented ARI episode to eliminate the possibility of unrelated usage. We also eliminated any OTC medication that would not be used for ARI. Costs were calculated on a per-dose basis using generic forms of all reported medications with prices retrieved from a national retail outlet (http://www.walgreens.com/; accessed on 4 March 2013). For those medicines where costs were not available online, prices were obtained from a local pharmacy. We conservatively set our regimen duration at 6 days and followed package dosage recommendations.

Antibiotics.

Participants were also asked to report any ARI-related antibiotic prescriptions taken during the same 2-week recall. Antibiotics taken at the time of a reported ARI were included. Antibiotic prices were obtained from drugstore.com and dosage recommendations were obtained from drugs.com; accessed on 4 March 2013. Costs were calculated on a per-dose basis. Aside from one particular antibiotic that has a 5-day regimen duration (Azithromycin), all other regimens were set at 10 days.

Statistical methods

A Monte Carlo-based probability model compared ARI-related lost work time, ARI-related health care utilization costs and ARI-related medication costs for the three randomization groups.13 We created 1000 simulated samples of study patients using Monte Carlo bootstrap sampling with replacement from the original study data.14 In each simulation, we drew 50 meditation, 50 exercise and 50 control participants. Probability data incorporated into the bootstrap sampling model were derived from the reference cost data. We assumed that ARI-related health care visit costs were based on the Dirichlet distribution, with cell probability determined by ARI-related visit data collected from the DFM Data Warehouse. A randomly drawn per ARI-related health care visit cost was multiplied by the total number of ARI-related visits to establish the visit costs for each simulated sample group. Lost work time costs were drawn from a uniform distribution based on wage data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. The randomly drawn ARI-related cost per lost work day was multiplied by the number of ARI-related work days lost to determine work loss costs for the simulated samples. We performed pairwise comparisons of the simulated samples within each iteration of the Monte Carlo analysis to calculate differences in per patient ARI costs, ARI work day costs, ARI health care visit costs and ARI medication costs. Cost differences were plotted to approximate the sampling distributions for treatment effect on ARI cost. We computed 95% confidence intervals based on the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles from the sampling distributions. Pairwise equivalence tests were conducted with significance level set at P-value < 0.05. All analyses were performed with SAS Version 9.1.3.

Results

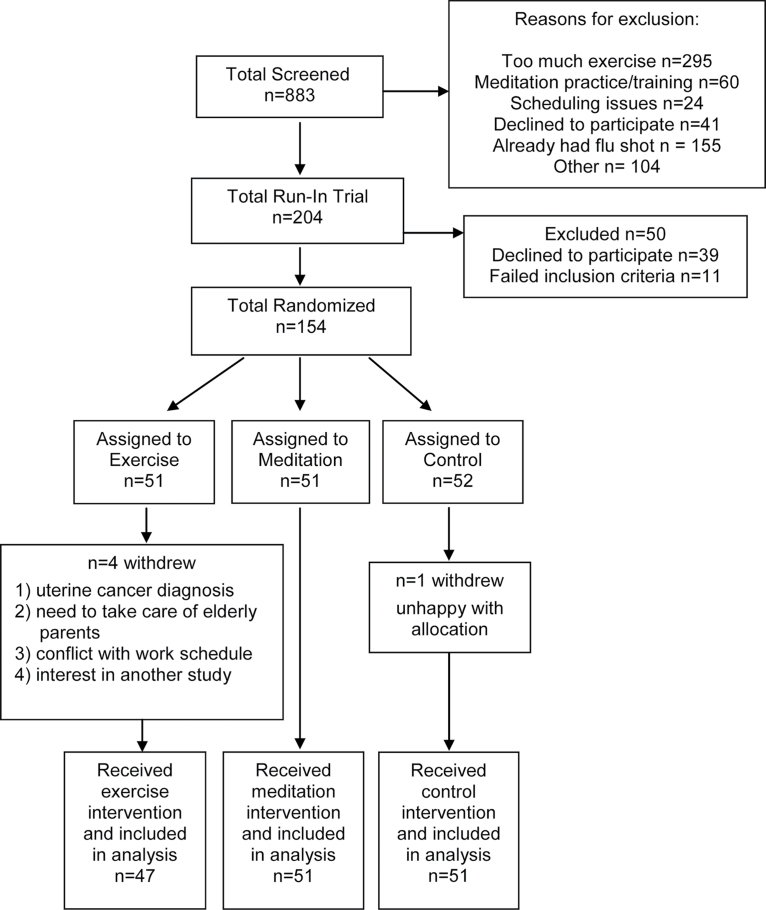

A total of 833 adults were screened. Of these, 204 participants entered a run-in trial and 154 were enrolled in the main study (Figure 1). Five participants withdrew from the study, for a total of 149 subjects included in the analysis (47 in exercise; 51 in both meditation and control).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram

Sample characteristics are summarized in Table 1. On average, study participants were ~60 years old, predominantly well-educated women, white, non-Hispanic and non-smokers. They were also overweight, with mean body mass index (BMI) nearing 30 m2/kg. Baseline demographic characteristics did not significantly differ among the groups.

Table 1.

Demographics of study population

| Exercise | Meditationa,b | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample (n) | 47 | 51 | 51 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 59.0 (6.6) | 60.0 (6.5) | 58.8 (6.8) |

| Female, n (%) | 39 (83.0) | 42 (82.4) | 41 (80.4) |

| Non smokers, n (%) | 43 (91.5) | 48 (94.1) | 48 (94.1) |

| Race | |||

| Black, n (%) | 3 (6.4) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (3.9) |

| White, n (%) | 43 (91.5) | 49 (92.5) | 48 (94.1) |

| Other, n (%) | 1 (2.1) | 3 (5.7) | 1 (2.0) |

| Ethnicity Non-Hispanic, n (%) | 47 (100) | 51 (100) | 49 (96.1) |

| BMI mean (SD) | 29.1 (6.6) | 29.0 (6.0) | 29.9 (6.7) |

| College graduate or higher, n (%) | 27 (57.5) | 36 (70.6) | 35 (68.6) |

| Income >$50 000, n (%) | 25 (53.2) | 31 (60.8) | 29 (56.9) |

aMissing information on income from meditation group (n = 2).

bOne person in the meditation group reported three racial categories.

Table 2 provides the counts of ARI-related lost work days, health care utilization and medication costs and total cost per subject across the study groups. Compared with control, fewer subjects experienced ARI and in general fewer ARI episodes of a shorter combined duration (total days) were reported in the two experimental groups (P < 0.05). The meditation group missed 16 days of work compared with 32 in the exercise group and 67 in the control group. Members of the Meditation group had 10 health care visits compared with 15 in the exercise group and 16 in the control group. The meditation group experienced the lowest number of lost work days, health care visits and medication costs.

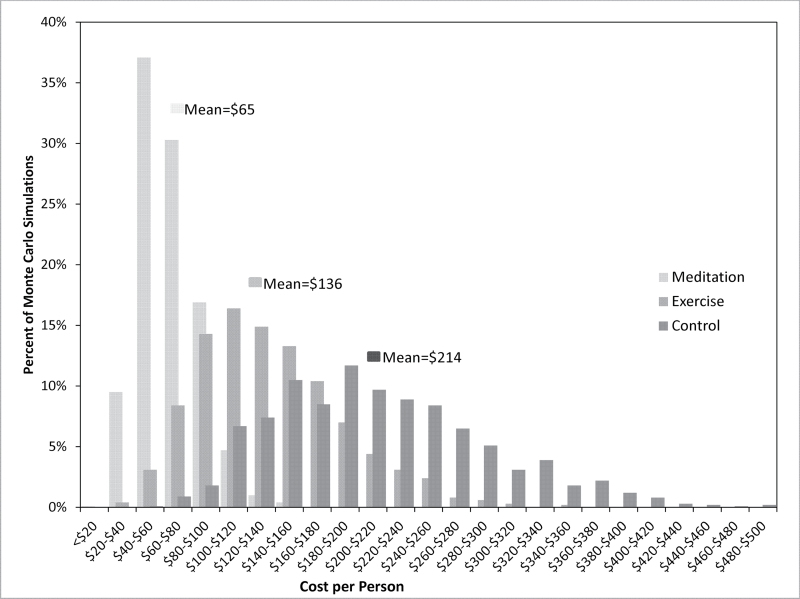

The above data were then used to populate probability data based on Monte Carlo boot strap analysis. Figure 2 displays the sampling distribution of total ARI-related costs per patient for the three arms of the study. The meditation group had the lowest overall ARI costs, at $65 per subject (95% confidence interval: $34–$104) (P = 0.010 compared with control group). In >70% of the meditation group sample runs, total ARI-related costs were <$80 per person. The exercise group was next least costly (P = 0.334 compared with control group), with a total ARI cost of $136 per subject (95% CI: $64–$232). The most costly group was the control group, with an ARI-related simulated cost $214 per subject (95% CI: $105–$358). In 1.5% of the simulated samples, the control group costs exceeded $400 per person.

Figure 2.

Cost of ARI-related clinic visits, lost work days and medications by intervention group

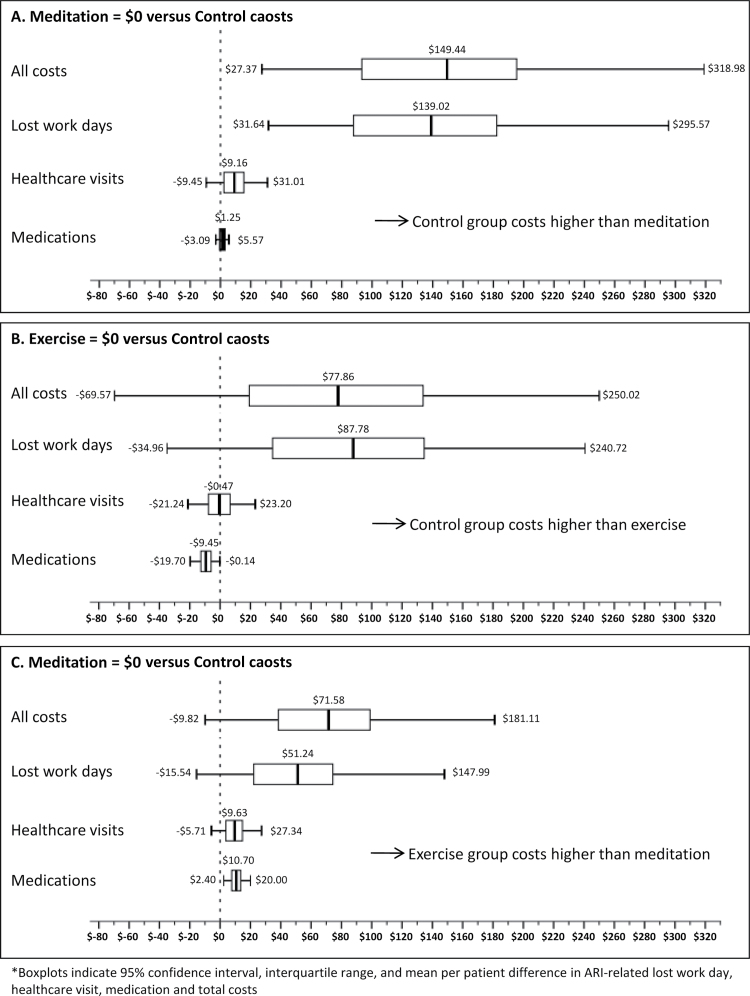

Figure 3 demonstrates sensitivity analyses for pairwise comparisons of the treatment groups. In a head-to-head comparison between meditation and control, the ARI-related cost difference was $149.40 per subject in favour of the meditation group (P = 0.010). The cost difference was driven primarily by a reduction in ARI-related lost work days ($139.00, P = 0.004). Meditation subjects also had $9.20 (P = 0.310) in savings from reductions in ARI-related health care visits. Comparing meditation to exercise, the meditation group had $71.60 per subject less ARI-related total costs (P = 0.116), with $51.20 (P = 0.156) coming from fewer ARI lost work days, $9.60 (P = 0.172) from reduced ARI-related health care visits, and $10.70 (P = 0.004) savings in ARI-related medications. In the final comparison, the exercise group cost less overall than the control group (P = 0.334), with the ARI-related lost work time category accounting for most of this difference. The difference in costs due to lost work days was $87.80 in favour of the exercise group (P = 0.198), but the exercise group had more health care visit costs ($0.50; P = 0.868) and medication costs ($9.40; P = 0.046) than the control group.

Figure 3.

Pairwise comparison of intervention group costs

Conclusions

Value is increased with improved quality at a lower cost. The previously published MEPARI study6 showed improved quality with a reduction in incidence, severity and duration of ARI with meditation and exercise. This study completes the value equation by showing reduced cost. Comparing the meditation group ($65 per person) with the control group ($214 per person) there was a significant reduction in total cost. If these findings were extrapolated to the general population, assuming Fendrick’s estimate of $40 billion spent annually on ARI, the cost savings could amount to ~$28 billion a year. Comparing the exercise group ($136) to the control group ($214) corresponds to as much as $14 billion in annual savings. Meditation ($65) had lower cost than the exercise group ($136) and yet despite having more episodes of ARI, meditators missed fewer days of work. Although the overall costs were reduced in the exercise group compared with control group, it may be worth noting that the exercise group had the highest costs for both health care visits and medication costs.

A limitation and challenge is the fact that we did not include the cost of the meditation and exercise classes (~$450) in the cost estimates. Inclusion would negate the initial cost savings for ARI but not the potential long-term benefits that would accrue from these healthy behaviours. Value of positive lifestyle behaviours take time to appreciate and we believe that these interventions would be undervalued if we limited their benefit to just one ARI season. The challenge is knowing where education fades and when there is a need to reinvest to encourage these behaviours. For example, mindfulness training has shown long-term beneficial effects in the treatment of people diagnosed with anxiety disorders, an effect that lasted up to 3 years after the initial intervention.15 And in the top 10% of highest-spending insurance enrollees in Quebec, those who practiced Transcendental Meditation had 28% lower cost after 5 years compared with those who did not practice.16

Our cost estimates were conservative. The majority of the costs associated with ARI were related to missed days of work. On average, for every dollar spent on wages for a missed day of work, two more dollars are spent on lost productivity.17 We included only the cost associated with daily wage and did not include costs associated with lost productivity. Our estimates for health care visit and medication costs were also conservative. We used average Medicare reimbursement charges for the cost of an ARI-associated office visit, and generic costs of OTC cold remedies and antibiotics. One could argue that we significantly underestimated true costs and therefore true potential cost savings.

Limitations of this study include an older sample (≥50 years) that may have a different incidence of ARI than a younger population. The missed days of work in an older sample may be difficult to extrapolate to a younger population that is more active in career work hours. Another limitation was with imputation of wage and health care visit costs. A larger sample, with more complete wage and health care billing data, would provide more precise estimates of cost savings with more statistical significance.

As the cost of health care continues to climb, it will be imperative to invest in health interventions that add value by improving outcomes at a reduced cost. Mindfulness stress reduction and exercise both appear to add value. This has already been established for exercise, but the significant cost savings for mindfulness was surprising. Encouraging self-reflection towards awareness of the present moment non-judgmentally may have health and financial benefits that extend beyond stress reduction and the duration of one ARI season.

Declaration

Funding: The Meditation and Exercise for the Prevention of Acute Respiratory Illness Trial was funded through the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine , The National Institutes of Health (BB). Trial Registration: Clinicaltrials.gov NCT01057771.

Conflict of interest: None of the authors has ownership interest or affiliation with any commercial or for-profit company or program involved with exercise or meditation training.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the mindfulness teachers and exercise physiologists at the University of Wisconsin for their participation and teaching of the participants of this study. Their expertise in their respective fields, we feel, played a significant role in support of our findings.

Authors’ Contributions: DR (MD) was the Principal Investigator of this research and supervised data analysis, wrote the manuscript and is responsible for interpretation of results. All co-authors contributed substantially and approved the final manuscript. DR and all co-authors had full access to all of the study data and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1. Davis K, Stremikis K. Family medicine: preparing for a high-performance health care system. J Am Board Fam Med 2010; 23 (Suppl 1): S11–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaplan RS, Porter ME. How to solve the cost crisis in health care. Harv Bus Rev 2011; 89 46–52, 54, 56–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mayes R. Moving (realistically) from volume-based to value-based health care payment in the USA: starting with medicare payment policy. J Health Serv Res Policy 2011; 16 249–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med 2010; 363 2477–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fendrick AM, Monto AS, Nightengale B, Sarnes M. The economic burden of non-influenza-related viral respiratory tract infection in the United States. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163 487–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Barrett B, Hayney MS, Muller D, et al. Meditation or exercise for preventing acute respiratory infection: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med 2012; 10: 337–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barrett B, Brown RL, Mundt MP, et al. Validation of a short form Wisconsin Upper Respiratory Symptom Survey (WURSS-21). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009; 7: 76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Proc 2003; 10: 144–55 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carmody J, Baer RA. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J Behav Med 2008; 31: 23–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fleming SM, Mars RB, Gladwin TE, Haggard P. When the brain changes its mind: flexibility of action selection in instructed and free choices. Cereb Cortex 2009; 19: 2352–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Borg G, Linderholm H. Exercise performance and perceived exertion in patients with coronary insufficiency, arterial hypertension and vasoregulatory asthenia. Acta Med Scand 1970; 187: 17–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Romeo J, Wärnberg J, Pozo T, Marcos A. Physical activity, immunity and infection. Proc Nutr Soc 2010; 69: 390–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Robert C, Casella G. Monte Carlo Statistical Methods 2ndedn. New York: Springer, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. New York: Chapman and Hall, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miller JJ, Fletcher K, Kabat-Zinn J. Three-year follow-up and clinical implications of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction intervention in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1995; 17: 192–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Herron RE. Changes in physician costs among high-cost transcendental meditation practitioners compared with high-cost nonpractitioners over 5 years. Am J Health Promot 2011; 26: 56–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davis K, Collins SR, Doty MM, Ho A, Holmgren A. Health and productivity among U.S. workers. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2005; 1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]