Abstract

Congenital absence of tibia is a rare anomaly, and may be total or partial, unilateral or bilateral. Total absence is more frequent than partial, unilateral absence occurs more often than bilateral, with right limb more commonly affected than the left. In partial defect, almost always the distal end of the bone is affected, and of the bilateral cases, there may be total absence on both sides, or total on one side and partial on the other. Males are slightly more commonly affected than the females. Though, the family history is usually negative for congenital abnormalities and other diseases, there is a considerable chance of occurrence of congenital defect of the tibia or of other abnormalities, in near or remote relatives. We report a case of newborn having bilateral tibial hemimelia type VIIa.

Keywords: Aplasia, congenital anomaly, tibial defect, tibial hememelia

Introduction

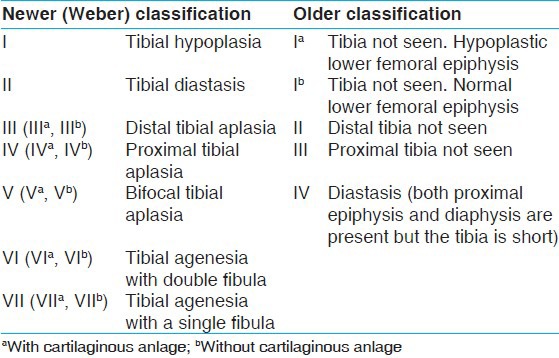

Tibial hemimelia is a very rare disease with an incidence of 1 in 1,000,000 live births.[1] It is characterized by deficiency of tibia with relatively intact fibula. It causes marked shortening of the involved extremity with a severe equinovarus deformity.[2] The defect could be either complete or incomplete, and occurs either as a solitary disorder, or as a part of more complex malformation syndrome.[1,3] Associated abnormalities include those of the musculo-skeletal system of both lower and upper limbs, oro-facial part, uro-genital, and cardiovascular systems. The tibial reduction defects were initially classified into 4 major types based only on X-ray findings,[4] however, later expanded to seven major types and five sub-groups according to the therapeutic relevance and considering the importance of cartilaginous anlage [Table 1].[5] According to the Weber-classification the sequence of the distribution of tibial hemimelia types is as follows: 62% of cases with type-VII, 15% with type-III, 6% with type-I, 6% with type-V, 5% with type-II, 3% with type-IV, and 3% with type-VI. If the older-classification corresponds to Weber-classification, then the sequence of the distribution would have been as follows: 61% of cases with type-I, 16% with type-II, 5% with type-IV, 3% with type-III, and 15% with not otherwise specified. We describe a rare case of bilateral tibial hemimelia that would be classified as type-I in older-classification, however, type-VII according to the Weber-classification.

Table 1.

Classification of tibial hemimelia

Case Report

A male infant was born at 38 weeks gestation to a 28-year-old Gravida 3, Para 2, mother with two living issue. Except for fever of 1 week duration (cause not known) during the first trimester, the antenatal period was mostly uncomplicated, without any history of diabetes or hypertension. His mother was a non-smoker, but had undergone chest X-ray once during the first trimester for fever work-up. There was no history of any teratogenic drug intake by the mother including routine multivitamin supplementation also.

Antenatal ultrasound carried out in another hospital showed normal amount of amniotic fluid. Abnormalities, all located in the bilateral lower limbs included, club-foot, tibial agenesis, and distal femoral bifurcation. The upper limbs were normal, and there were no other notable malformations. Previous pregnancies were normal without any gross congenital malformations. Parents were of Indian descent with no evidence of consanguinity.

He was born by elective caesarean-section (indication being previous caesarean-section secondary to failed induction), with APGAR score being, 8/10 and 9/10. His birth weight was 2.9 kg (appropriate for gestational age), head circumference was 33.5 cm (50-75th centile), and upper segment length was 29 cm (normal). He did not require any intervention at birth.

On examination, both knees were flexed and held at 30°. Both feet showed equinovarus deformity. The leg segment was internally rotated to 60° bilaterally and bony prominence was seen on the lateral aspect of the knee joint on both sides [Figure 1]. The child had an absent quadriceps mechanism with dysfunctional knee and ankle joints bilaterally. Voluntary extension and flexion was absent on both knees. The radiological evaluation revealed a normal hip joint. The lower end of femur was normal and patella was present. Complete absence of both tibiae was noted with small cartilaginous anlage, and fibula was present on both legs without any sign of doubling [Figure 2]. Calcaneus was displaced anteriorly and was higher than the lower end of fibula. Both the right and left foot had three tarsal bones, two metatarsals, and three toes each having two phalanges each [Figure 2]. The musculo-skeletal system of upper limb did not reveal any abnormality, and there was no dysmorphic facies. Systemic examination also did not reveal any abnormality, except that the genitalia were dark pigmented. The newborn was started on breast-feeding, which he was accepting well.

Figure 1.

Photograph of the newborn showing deformed lower limbs, normal upper limbs, and darkly pigmented genitalia

Figure 2.

X-ray showing normal hip joint, normal lower end of femur, complete absence of both tibiae with small cartilaginous anlage, and presence of fibula on both legs. Both the right and left foot had three tarsal bones, two metatarsals, and three toes each having two phalanges each

Discussion

The limb defects appear to have a multifactorial etiology, arising from an interaction between environmental influences, teratogenic exposure and the individual's genetic makeup. Tibial hemimelia syndrome, which is a rare autosomal dominant condition, encompasses several types of syndrome, all having a common phenotype of tibial hypoplasia or agenesis and polydactyly.[6] Family history of congenital anomaly of tibia, as well as intra-familial phenotypic variations of the defect in twin pregnancy has been reported.[7,8,9] The anomalies in which the number of skeletal elements increased arise during the first 7 weeks of intrauterine life. A decrease in the number of skeletal parts may arise after, as well as during, this 7-week period.[10] The mother of the index case was suffering from pyrexia of unknown origin during the first trimester, and this might have led to the defect by its interaction with some unidentified environmental influences and absent intake of multivitamin supplementation by the mother.[11]

As described above, tibial hemimelia is usually accompanied by other congenital anomalies that include; congenital dislocation of the hip, ectro-, poly-, or syn-dactyly, abnormalities of the musculo-skeletal system of both lower and upper limbs, phocomelia, harelip and cleft palate, pseudo-hermaphroditismn, cryptorchidism, and hypospadias, etc., One report described a case of tibial hemimelia, femoral bifurcation, cleft lip/palate, and cardiovascular anomaly like atrioventricular canal with truncus arteriosus.[12] However, in the index case, though there was bilateral tibial hemimelia with foot ectrodactyly, systemic malformations were absent except for the hyperpigmented genitalia.

Some cases of tibial hemimelia are genetically transmitted, whereas others are sporadic. Few syndromes such as tibial hemimelia–foot polydactly triphalangeal thumbs syndrome (Werner syndrome), tibial hemimelia diplopodia syndrome, tibial hemimelia–split hand/foot syndrome, tibial hemimelia–micromelia–trigonobrachycephaly syndrome, tibial hemimelia–normal upper limb syndrome and tibial hemimelia–radial agenesis syndrome are considered to be transmitted as autosomal dominant. In others such as, tibial hemimelia–cleft lip/palate syndrome, tibial hemimelia split hand/foot syndrome, an autosomal recessive inheritance is suggested.[13]

Treatment mainly includes surgical correction of the deformity where possible. Common surgical procedures include disarticulation at Knee, Syme's amputation or Chopart amputation.[2,7] The sooner the amputation is performed the easier and faster the rehabilitation and adaptation to the prosthesis. The absence of the cartilaginous anlage increases the difficulty of the operative procedure. The surgical option for the index case with favorable result would include disarticulation of the knee joint and prosthesis.[2]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Fernandez-Palazzi F, Bendahan J, Rivas S. Congenital deficiency of the tibia: A report on 22 cases. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1998;7:298–302. doi: 10.1097/01202412-199810000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weber M. Congenital leg deformities: Tibial hemimelia. In: Rozbruch SR, Ilizarov S, editors. Limb Lengthening and Reconstruction Surgery. New York: Informa Health Care; 2007. pp. 429–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuyama J, Mabuchi A, Zhang J, Iida A, Ikeda T, Kimizuka M, et al. A pair of sibs with tibial hemimelia born to phenotypically normal parents. J Hum Genet. 2003;48:173–6. doi: 10.1007/s10038-003-0003-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henkel HL, Willert HG, Gressmann C. An international terminology for the classification of congenital limb deficiencies. Recommendations of a working group of the international society for prosthetics and orthotics (author›s transl) Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1978;93:1–19. doi: 10.1007/BF00386546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber M. New classification and score for tibial hemimelia. J Child Orthop. 2008;2:169–75. doi: 10.1007/s11832-008-0081-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richieri-Costa A, Ferrareto I, Masiero D, da Silva CR. Tibial hemimelia: Report on 37 new cases, clinical and genetic considerations. Am J Med Genet. 1987;27:867–84. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320270414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoenecker PL, Capelli AM, Millar EA, Sheen MR, Haher T, Aiona MD, et al. Congenital longitudinal deficiency of the tibia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:278–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leite JA, Lima LC, Sampaio ML. Tibial hemimelia in one of the identical twins. J Pediatr Orthop. 2010;30:742–5. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181edba12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dayer R, Ceroni D, Bottani A, Kaelin A. Tibial aplasia-hypoplasia and ectrodactyly in monozygotic twins with a discordant phenotype. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27:266–9. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3180340d6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frantz CH, Rapids G, O’Rahilly R. Congenital skeletal limb deficiencies. J Bone and Joint Surg. 1961;43A:1202–24. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Botto LD, Erickson JD, Mulinare J, Lynberg MC, Liu Y. Maternal fever, multivitamin use, and selected birth defects: Evidence of interaction? Epidemiology. 2002;13:485–8. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200207000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erickson RP. Agenesis of tibia with bifid femur, congenital heart disease, and cleft lip with cleft palate or tracheoesophageal fistula: Possible variants of Gollop-Wolfgang complex. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;134:315–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richieri-Costa A. Tibial hemimelia-cleft lip/palate in a Brazilian child born to consanguineous parents. Am J Med Genet. 1987;28:325–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320280209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]