Abstract

The world of communication has changed greatly over the centuries of mankind from sounds, sign languages, speech, development of language and in modern times using machines like the computer, mobile and internet. Over the past five decades, the change in communication is remarkable. Similarly positive patient communication is always necessary to build confidence, increased rapport and cooperation and minimizes misunderstanding. Returning the patient in our fold promotes the patient for further preventive care and review and using them as a positive tool helps us in an ambassador of the growth of our health care unit. Our challenge is to provide the best environment for communication with a diverse population of interest, personalities and culture.

Keywords: Communication, dentistry, orthodontics, patient

The world of communication has changed greatly over the centuries of mankind from sounds, sign languages, speech, development of language and in modern times using machines like the computer, mobile and internet. Over the past five decades, the change in communication is remarkable. Similarly positive patient communication is always necessary to build confidence, increased rapport and cooperation and minimizes misunderstanding. Returning the patient in our fold promotes the patient for further preventive care and review and using them as a positive tool helps us in an ambassador of the growth of our health care unit. Our challenge is to provide the best environment for communication with a diverse population of interest, personalities and culture. In this paper, a brief review will be presented to illustrate and provide some evidence for the importance of effective communication in dentistry.

Review of Literature

Gale et al. studied a group of 16 patients who received Class II restorations at two different sessions. During one session a dentist interacted positively with the patient. During another session, the dentist had little interaction with the patients. Patients′ ratings indicated that both dentists were perceived as equally competent but that the dentist who interacted with the patients was rated significantly better. It is possible that dentists will gain more satisfaction from their patients as they increase their interaction.[1]

ter horst and de wit reviewed the behavioral research in dentistry published during 1987-1992 on dental anxiety, dentist-patient relationship, compliance and dental attendance. In this article they concluded that little progress has been made in the field of behavioral dentistry during those years and recommendations were made to improve future research efforts.[2]

Lahti et al. studied on ideal dentist - patient expectation. The samples (n = 271) were from community health centers and private clinics in different parts of Finland. Equal numbers of regular and irregular clients were invited to participate. Before the treatment procedure, each patient filled out a questionnaire with forty Likertian statements dealing with their expectations of an ideal dentist, and nine about their own background, i.e., age, sex, regularity of dental visits, basic and professional education and occupation of the treatment subjects described their treating dentists′ behavior using similar statements. In the analyses two approaches were applied. First, factor analyses with orthogonal varimax rotation were conducted with the data about the ideal and actual dentist. For the ideal dentist, five factors were extracted: (1) mutual communication, (2) fair support, (3) personal appearance, (4) preferred type of practice, and (5) blaming; and for the actual dentist five factors were extracted: (1) mutual communication, (2) pain control, (3) fair support, (4) personal appearance, and (5) preferred type of practice.[3]

In patient-dentist relationship study Mataki et al. has discussed the scope of the review which has been confined to behavioral researches published mainly in the past two decades especially on patient-dentist relationship, dental anxiety, communication and patients′ satisfaction. In summary, they concluded that there was not so much progress during the period in the field of behavioral dentistry. Consequently, several recommendations are suggested for a future study of behavioral dentistry.[4]

In another study Schouten et al. examined the relations between patients′ and dentists’ communicative behavior and their satisfaction with the dental encounter. The sample consisted of 90 patients receiving emergency care from 13 different dentists. Consultations were videotaped in order to assess dentists’ and patients’ communicative behavior. Dentists’ behavior was coded by means of the Communication in Dental Setting Scale, scores for patients’ behavior included among other things, the number of questions asked during the consultation. Finally Schouten et al. concluded that not only patients’ satisfaction is positively related to the communicative behavior of dentists, but the principle of informed consent requires dentists also to inform their patients adequately enough for them to reach a well-informed decision about the treatment. Therefore, it remains important to train dentists in communicative skills.[5]

Veldhuis and Schouten have explained that the patient satisfaction is a rather complicated issue. This paper describes the results of a pilot study regarding the influence of dentists’ communication styles on patient satisfaction. A distinction was made between an affective and a control style. The study was conducted among 11 dentists and 22 patients. The results of this study indicated that dentists’ communication styles were somewhat associated with patient satisfaction. It was suggested that dentists should not only give information to patients adequately, but should also pay attention to their personal communication style.[6]

In another study, Yamalik has discussed that, besides technical expertise, the success of dental care depends on the behavioral patterns of the dentist and the patient and the way they interact with each other. Since communication is involved in the process of care, in many ways it is a ’key’ concept of this interaction. As patient satisfaction and quality care are closely related with the dentist’s positive attitudes and communicative skills, dentists need to focus on patients as ’individuals’ and have ’real’ communication with them.[7]

In another study Rozier et al. conducted a national survey to determine the communication techniques that dentists use routinely and variations in their use. American Dental Association Survey Centre staff members mailed an 86-item questionnaire to a random sample of 6,300 U.S. dentists in private practice. Participants reported routine use (“most of the time” or “always”) during a typical week of 18 communication techniques, of which seven are basic techniques. The authors used analysis of variance and ordinary least squares regression models to test the association of communication, provider and practice characteristics with the number of techniques. Finally concluded routine use of all of the communication techniques is low among dentists, including some techniques thought to be most effective with patients with low literacy skills. Professional education is needed to improve knowledge about communication techniques and to ensure that they are used effectively. A firm foundation for these efforts requires evelopment.[8]

In another study Ukra et al. has discussed that the orthodontist-patient relationship may have a significant impact on treatment outcome and patient satisfaction, thus improving the overall quality of care. Effective communication is crucial and unfortunately, it is often underestimated in a busy clinical practice. Aim of part one of this article is to review the psychological aspects that are relevant to a number of treatment variables in clinical orthodontics, including compliance with treatment, oral hygiene, management of orthodontic pain and discomfort, and oral habits. Due to the complex nature of the psychology of orthodontic treatment, it is difficult to determine the extent of the influence that the orthodontist-patient relationship may have on these variables, with effective communication and an awareness of the psychological issues playing an important role in enhancing the orthodontist-patient relationship.[9]

In another study, Carr et al. has studied that the comprehension of informed consent information has been problematic. The purposes of this study were to evaluate the effectiveness of a shortened explanation of an established consent method and whether customized slide shows improve the understanding of the risks and limitations of orthodontic treatment. In this slide shows for each of the 80 subject-parent pairs included the most common core elements, up to 4 patient-specific custom elements, and other general elements. Group A heard a presentation of the treatment plan and the informed consent. Group B did not hear the presentation of the informed consent. All subjects read the consent form, viewed the customized slide show, and completed an interview with structured questions, literacy tests, and a questionnaire. The interviews were scored for the percentages of correct recall and comprehension responses. Three informed consent domains were examined: Treatment, risk, and responsibility. These groups were compared with a previous study group, group C, which received the modified consent and the standard slide show. Finally he has concluded that this study suggested little advantage of a verbal review of the consent (except for patients for risk) when other means of review such as the customized slide show were included. Regression analysis suggested that patients understood best the elements presented first in the informed consent slide show. Consequently, the most important information should be presented first to patients, and any information provided beyond the first 7 points should be given as supplemental take-home material.[10]

In another study Ukra et al. has discussed that the Orthodontists tend to treat see their patients on a systematic, recurrent basis, often during crucial stages of psychological development. Therefore, they have a pivotal role in identifying a number of psychological as well as of psychiatric disorders. Effective communication is crucial and unfortunately, it is often underestimated in a busy clinical practice. Author reviewed the role clinical orthodontics and the orthodontist-patient relationship have on the patients’ psychosocial wellbeing, including effects on self-esteem, bullying and harassment by peers, and even several psychiatric disorders, such as anorexia/bulimia nervosa, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders. Due to the complexity and importance of these issues, the orthodontist may play a dynamic role, not only in the management of dental malocclusions, but at times, as “psychologist” and a counselor to the patient.[11]

In Ethics in orthodontics Peter discussed about communication in the face of conflict is difficult for almost everyone. Your first intention should be to maintain ’veracity’ (truth telling). In managing situation of potential conflict, the patients, the parents, and all providers involved need to know a straight forward, accurate, and bias-free account of what has occurred. This communication is the first step in re-establishing trust as well as defining the patient as a person rather than as a procedure or a subject.[12]

Adult orthodontic therapy is now an accepted component of contemporary oral healthcare. All our patients especially adults, must be provided with opportunity to express their autonomy in treatment planning. Discussions involving the difference between removable and fixed appliance therapy, extraction versus non extraction comparison, surgical and non-surgical plans, and so on should all be approached by frank discussions elucidating the scope of pros and cons of each treatment option. It has been shown that 65% of adult orthodontic patients require dual or multiple provider groups in collaborative management.[13,14]

Hence, therapist needs to provide sufficient information in treatment planning to ensure that the patient is offered maximum autonomy in making treatment decisions. The orthodontist should verify that this has occurred when multiple providers are involved in treatment. This is essential from both ethical and legal perspectives.[14]

Robin Wright has given the skills that is necessary for the improvement of dentist patient relationship.[15]

Build rapport with patients.

Encourage patients to take an active role in their dental care.

Listen effectively to patients.

Respond to difficult patient questions.

Explain dental conditions and treatment needs.

Manage financial discussions.

Communicate effectively with other team members.

Convince patients to accept treatment recommendations.

Speak to patients with confidence and assertiveness.

Resolve conflicts with team members.

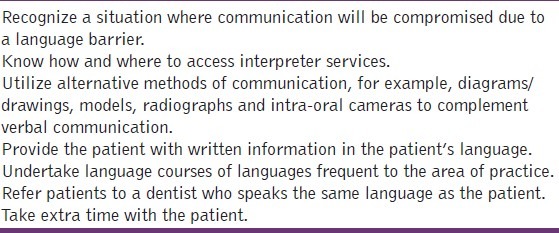

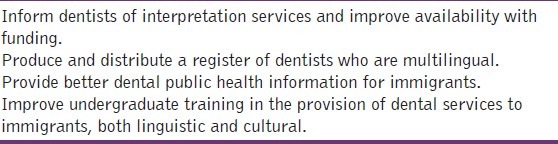

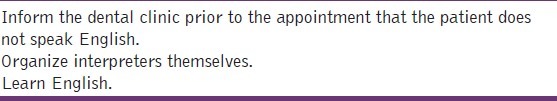

Goldsmith et al. have given suggestions to the dentist, patient and the governing body of dentistry[Table 1–3.[16]

Table 1.

Suggestions for action the dentist may take

Table 3.

Suggestions for action the governing bodies of dentistry may take

Table 2.

Suggestions for action the patient may take

Discussion

The world of communication has changed greatly over the centuries of mankind from sounds, sign languages, speech, development of language and in modern times using machines such us the computer, mobile and internet. Over the past five decades, the change in communication is remarkable. Similarly positive patient communication is always necessary to build patient confidence, increased rapport and co-operation and minimizes misunderstanding. Returning the patient in our field, promotes the patient for further preventive care and reviewing and using them as a positive tool helping us as an ambassador of the growth of our health care unit.

In the very first appointment, one should converse with a new patient in caring and concerned manner and build confidence and explain the problems and the treatment measures. Communication should bring ideas for us regarding the family, education, job, financial background and personal history of the patient. This will also give more bond to know the personality of the patient, whether the patient is suited for a particular dental procedure. This will help us in handling the patient for a couple of years actively and throughout the life for reviewing.

Some children who started orthodontic patients come back to the same center for the treatment, for their children. This shows the profound confidence and bond the patient exhibits with the dentist or orthodontist. Children and adults, nowadays show more individualism. We have to slowly get into their boundaries to find ways for positive communication. There was an instance in our practice when an orthodontic patient was non-cooperative and this was identified by the sibling who accompanied. Siblings always give us the inside factor of non-cooperation. Many mothers may not reveal the non-cooperation for losing the image of the kid or the family. With the positive interaction with the dentist and the orthodontist, patients improve their knowledge, positive behavior for their future interactions, ideas of education and new environment is known. Some kids who accompany their siblings for orthodontic treatment take up the dentistry course as a passion.

Conclusions

It is always better to educate the patient about the disease and treatment planning.

Better to be transparent and truthful with the patient.

Give the utmost dental care and show great concern.

Gaining confidence and maintaining the confidence.

Listening to the patient, alleviating fear, misconception and misunderstanding about the disease.

Understanding the psychology of the patient, family and friends.

Speaking in the regional languages and dialects.

Proper reviewing of the disease and treatment planning and motivation.

Use of specialist knowledge in a given situation.

Give positive new ideas for overcoming the disease and give innovative in-puts for a given dental situation.

Motivating the health care team to have a same attitude as that of the operator towards patient and family.

All this will positively help in a successful communication with the patient.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Gale EN, Carlsson SG, Eriksson A, Jontell M. Effects of dentist’s behavior on patient’s attitudes. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;109:444–6. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1984.0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ter Horst G, de Wit CA. Review of behavioural research in dentistry 1987-1992: Dental anxiety, dentist-patient relationship, compliance and dental attendance. Int Dent J. 1993;43:265–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lahti S, Tuutti H, Hausen H, Käärlänen R. Patients’ expectations of an ideal dentist and their views concerning the dentist they visited: Do the views conform to the expectations and what determines how well they conform? Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24:240–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1996.tb00852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mataki S. Patient-dentist relationship. J Med Dent Sci. 2000;47:209–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schouten BC, Eijkman MA, Hoogstraten J. Dentist’s and patient’s communicative behaviour and their satisfaction with the dental encounter. Community Dent Health. 2003;20:11–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veldhuis B, Schouten BC. The relationship between communication styles of dentists and the satisfaction of their patients. Ned Tijdschr Tandheelkd. 2003;110:387–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamalik N. Dentist-patient relationship and quality care 3.Communication. Int Dent J. 2005;55:254–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2005.tb00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rozier RG, Horowitz AM, Podschun G. Dentist-patient communication techniques used in the United States: The results of a national survey. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142:518–30. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2011.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ukra A, Bennani F, Farella M. Psychological aspects of orthodontics in clinical practice. Part one: Treatment-specific variables. Prog Orthod. 2011;12:143–8. doi: 10.1016/j.pio.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carr KM, Fields HW, Jr, Beck FM, Kang EY, Kiyak HA, Pawlak CE, et al. Impact of verbal explanation and modified consent materials on orthodontic informed consent. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2012;141:174–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ukra A, Bennani F, Farella M. Psychological aspects of orthodontics in clinical practice. Part two: General psychosocial wellbeing. Prog Orthod. 2012;13:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pio.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peter M. Grew communication in the face of conflict. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;140:5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Music DR. Assessment and description of the treatment needs of adult patients evaluated for orthodontic theraphy: Part I, II, III. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1986;1:55–67. 101–217, 251–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greco PM. Communicate, communicate, communicate. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2011;139:S15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American dental association center for continuing education and lifelong learning seminar series. Optimise your practice through powerful communication by Robin Wright. 2013. [Last accessed on 2013 April 30]. Available from: http://www.ridental.com.

- 16.Goldsmith C, Slack-Smith L, Davies G. Dentist-patient communication in the multilingual dental setting. Aust Dent J. 2005;50:235–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2005.tb00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]