Abstract

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSF) is a chronic, progressive, potentially malignant condition affecting the oral cavity and frequently involving the upper part of the aerodigestive tract including the oropharynx and the upper part of the esophagus. It is characterized by juxtaepithelial inflammatory reaction and progressive fibrosis of lamina propria, leading to stiffening of the oral mucosa eventually causing trismus. This condition is associated with significant morbidity and high risk of malignancy. Over the years, several drugs and combinations have been tried for the treatment of submucous fibrosis, but with limited success, because of its unclear molecular pathogenesis. Till date, there are no known effective treatments for OSF. The aim of this article is to emphasize on the molecular changes taking place in OSF and possible therapeutic interventions.

Keywords: Classification, oral submucous fibrosis, pathogenesis, treatment

Oral submucous fibrosis (OSF) is a chronic, progressive, potentially malignant condition of the oral cavity, which has the highest malignant transformation potential of 7-13%.[1,2] OSF is predominantly seen in people of Southern Asian countries or Southern Asian immigrants to the other parts of the world and now globally accepted as an Indian disease.[3,4] It is strongly associated with the use of areca nut in various forms with significant duration and frequency of chewing habits. It has been reported in the Indian literature since the time of Sushruta as ′Vidari′.[5] In 1952, Schwartz was the first to report a case of this type and in 1956, Paymaster identified its pre-cancerous nature. In 1966, Pindborg and Sirsat defined OSF as, “an insidious, chronic disease affecting any part of the oral cavity and sometimes the pharynx. Although occasionally preceded by and/or associated with vesicle formation, it is always associated with juxtaepithelial inflammatory reaction followed by fibroelastic changes in the lamina propria, with epithelial atrophy leading to stiffness of the oral mucosa causing trismus and inability to eat”.[6,7]

The most commonly involved site is buccal mucosa, followed by palate, retromolar region, faucial pillars and pharynx.[5] The overall prevalence rate in India is about 0.2-0.5% and prevalence by gender varying from 0.2% to 2.3% in males and 1.2% to 4.57% in females. The age range of the patients with OSF is wide ranging between 20 years and 40 years of age.[7] Ingestion of chilies, genetic susceptibility, nutritional deficiencies, altered salivary constituents, autoimmunity and collagen disorders may be involved in the pathogenesis of this condition.[3]

Pathogenesis

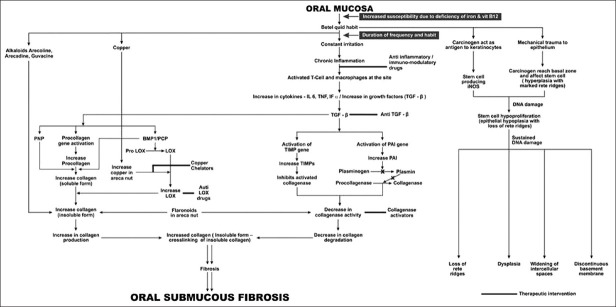

The exact mechanism is not clear yet. But the arecoline and flavonoid, components of areca nut when exposed to buccal mucosal fibroblast results in the accumulation of collagen. Reduced collagenase activity and increased cross-linking of the fibers results in decreased degradation of collagen. This evidence implies that OSF may be considered a collagen-metabolic disorder resulting from exposure to areca nut. The possible molecular alteration-taking place in epithelium and connective tissue has been explained in Figure 1.[1,2,8]

Figure 1.

Molecular pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis

Histopathology

The important histopathological characteristic of OSF is the deposition of collagen in the oral submucosa. Structural changes of epithelial and connective tissue in OSF have been studied in detail both at the light and electron microscopic levels. The epithelial finding ranges from hyperplastic to atrophic epithelium. The atrophic epithelium may exhibit loss of rete pegs, hyperkeratinization, intercellular edema, signet cells and focal dysplasia. It may also show vacuolization of prickle cell layer and increased mitotic activities in few cases. The observed epithelial changes are secondary to changes in connective tissue.

The connective tissue changes were graded based on presence or absence of edema, nature of the collagen bundles, overall fibroblastic response, State of the blood vessels and predominant cell type in the inflammatory exudates.[2]

Classification

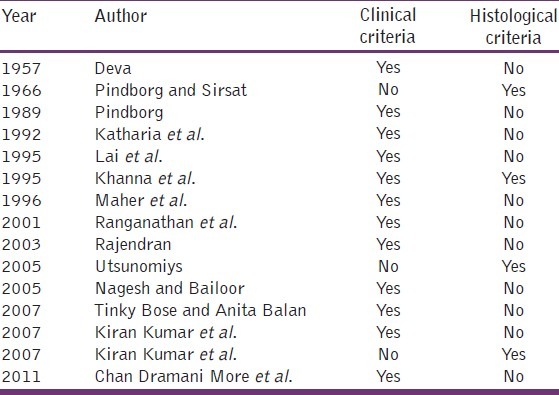

Several classifications based on clinical, histological and combined feature have been put forth by several researchers at several time periods is shown in Table 1.[9,10]

Table 1.

Criteria′s included by different authors

Malignant potential

The higher prevalence of leukoplakia as well as epithelial atypia in OSF leading to oral carcinoma was observed. One third of the patient with this disease has developed slow growing squamous cell carcinoma. The precancerous nature of this disease has been proved by, higher occurrence of OSF in oral cancer patients, Higher incidence of squamous cell carcinoma in patients with OSF, Histological diagnosis of cancer without any clinical suspicion in OSF, High frequency of epithelial dysplasia and Higher prevalence of leukoplakia among OSF. Initiation of malignancy in OSF occurs because of epithelium or connective tissue is still in debate.[2,11] But, it might be that the pathology develops within the epithelium due to intraoral trauma and various factors may play a significant role in oral cancer. The various factors causing oral trauma include, irritation from jagged teeth, ill-fitting denture, sharp overhanging restoration, jacket crowns, prolong use of tobacco and poor oral hygiene.[2,12]

Treatment

The main problems plaguing the patients with OSF are the burning sensation and progressive trismus which impedes normal function. The treatment should aim at alleviating the symptoms as well as try to stop the progression of fibrosis. The treatment modalities which are currently being used can be broadly divided into three main categories, viz.: Medical therapy, surgical therapy and physiotherapy. But, whatever the treatment method may be, the first step of preventive measure should be in discontinuation of habit, which can be encouraged through education, counseling and advocacy.[5,13]

Several studies have been performed to study the effects of various drugs in the management of OSF.[14,15] The main non-surgical methods of managing OSF include:

Corticosteroids are immunosuppressive agents, they inhibit action of inflammatory products released by sensitized lymphocytes.[16] They may be able to partly relieve patients of their symptoms, at an early stage, but less useful in reversing the abnormal deposition of fibrotic tissues and recovering the suppleness of the mucosa.[17]

Proteolytic enzymes such as hyaluronidase, collagenase and chymotrypsin are often used for the treatment of OSF. Hyaluronidase breaks down hyaluronic acid, and also decreases collagen formation. A combination of Triamcinolone 10 mg/ml + hyaluronidase 1500 IU[9] for 4 weeks or biweekly submucosal injections of a combination of dexamethasone (4 mg/ml) and two parts of hyaluronidase (200 usp. Unit/ml) diluted in 1.0 ml of 2% xylocaine have proven effective in the past.[18]

Vitamins, antioxidants and minerals: Lycopene is a such powerful antioxidant obtained from tomatoes, which given at a dose of 16 mg twice daily for 2 months showed significant improvement.

Levamisole: Immuno-modulatory drug, given at a dose of 50 mg tab Thrice in a day (TID) showed significant improvement in signs and symptoms. It modifies both cellular and humoral immunity, has an Anti-inflammatory effects and its ability to modulate inflammatory cytokines reduces burning sensation.[19–22]

Placental extract: They were found to have anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory activity and brought about reduction of bands, improvement in mouth opening and tongue protrusion.[23] But recent regulations in India allows usage of placental extracts only for topical wound healing and pelvic inflammatory diseases.

Interferon-γ: Has a known anti-fibrotic effect. When given in a dosage of 50 μg (0.25 ml) intralesionally twice a week over 8 weeks, recombinant human INF-γ showed improvement in both mouth opening and burning sensation. Adverse effects included simple headache, flu-like symptoms and myalgia.[24]

Peripheral vasodilators: Pentoxifylline has a vasodilating property, which when given at dosage of 400 mg, 3 times a day for 7 months showed better results when compared to a control group which was on only antioxidants.[25] It blocks TNF-α induced synthesis of fibroblast collagen.

Immune milk: Immune milk is a kind of skimmed, produced from cows immunized with multiple human intestinal bacteria.

Immune milk contains an anti-inflammatory component that may suppress the inflammatory reaction and modulate cytokine production. 45 g of milk powder prepared from an immunized cow, given twice a day for 3 months has found to show some improvement.[13]

Ayurvedic medicine: In India, turmeric has been used as a common household spice and has been used as a remedy for wound healing for centuries. In one clinical trial alcoholic extracts of turmeric 3 g, turmeric oil 600 mg and turmeric oleoresin 600 mg, when consumed orally, decreased the number of micronucleated cells both in exfoliated oral mucosal cells and in circulating lymphocytes in OSF patients.

Surgical therapy aims at relieving severe trismus by incising the fibrous bands, which has led to further fibrosis in the past. Improved techniques have been tried by placing either skin grafts or other alloplast membranes. LASER-CO2 laser surgery offers advantage in alleviating the functional restriction. Cryosurgery shows better treatment results in recent days.

Physiotherapy aims at bringing the oral tissues to its natural harmony. Muscle stretching exercises like ballooning of mouth, forceful mouth opening using splints and sticks have been tried in the past as a supportive therapy post-surgically.[13]

Conclusion

OSF is a crippling disease of the oral cavity. It is one of the most poorly understood and unsatisfactorily treated oral diseases because of its multifactorial etiology. No single drug has provided a complete relief and this is mainly due to the fact that the etiology of the disease is not fully understood. The better approach in demystifying the pathogenesis of OSF could provide a new and successful therapeutic direction in near future.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Sharma M, Sharma GK. Oral submucous fibrosis: An issue of carcinogenesis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2012;3:68–71. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Savita JK, Girish HC. Oral susmucous fibrosis: A review [Part 2] J Health Sci Res. 2011;2:37–48. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan S, Chatra L, Prashanth SK, Veena KM, Rao PK. Pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis. J Cancer Res Ther. 2012;8:199–203. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.98970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guta MK, Mhaske S. Oral submucous fibrosis: Current concepts in etioathogenesis. People′s J Sci Res. 2008;1:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chole RH, Gondivkar SM, Gadbail AR, Balsaraf S, Chaudhary S, Dhore SV, et al. Review of drug treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Oncol. 2012;48:393–8. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pindborg JJ, Sirsat SM. Oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;22:764–79. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(66)90367-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy V, Wanjari PV. Oral submucous fibrosis: Correlation of clinical grading to various habit factors. Int J Dent Clin. 2011;3:21–4. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_92_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rajalalitha P, Vali S. Molecular pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis: A collagen metabolic disorder. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:321–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.More CB, Gupta S, Joshi J, Varma SN. Classification system for oral submucous fibrosis. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2012;24:24–9. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ranganathan K, Mishra G. An overview of classification schemes for oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2006;10:55–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pindborg JJ. Is submucous fibrosis a precancerous condition in the oral cavity? Int Dent J. 1972;22:474–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dayal, Reddy R, Anuradha Bhat K. Malignant potential of oral submucous fibrosis due to intraoral trauma. Indian J Med Sci. 2000;54:182–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taneja L, Nagpal A, Vohra P, Arya V. Oral submucous fibrosis: An oral physician approach. J Innov Dent. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta D, Sharma SC. Oral submucous fibrosis-A new treatment regimen. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 1988;46:830–3. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(88)90043-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang X, Hu J. Drug treatment of oral submucous fibrosis: A review of the literature. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;67:1510–5. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2008.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borle RM, Borle SR. Management of oral submucous fibrosis: A conservative approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:788–91. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kakar PK, Puri RK, Venkatachalam VP. Oral submucous fibrosis: Treatment with hyalase. J Laryngol Otol. 1985;99:57–9. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100096286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kumar A, Bagewadi A, Keluskar V, Singh M. Efficacy of lycopene in the management of oral submucous fibrosis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:207–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jirge V, Shashikanth MC, Ali IM, Nisheeth A. Levamisole and antioxidants in the management of oral submucous fibrosis: A comparative study. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2008;20:135–40. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haque MF, Meghji S, Nazir R, Harris M. Interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) may reverse oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:12–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.300103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katharia SK, Singh SP, Kulshreshtha VK. The effects of placental extract in management of oral sub-mucous fibrosis. Indian J Pharm. 1992;24:181–3. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rajendran R, Rani V, Shaikh S. Pentoxifylline therapy: A new adjunct in the treatment of oral submucous fibrosis. Indian J Dent Res. 2006;17:190–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.29865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tai YS, Liu BY, Wang JT, Sun A, Kwan HW, Chiang CP. Oral administration of milk from cows immunized with human intestinal bacteria leads to significant improvements of symptoms and signs in patients with oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:618–25. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.301007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hastak K, Lubri N, Jakhi SD, More C, John A, Ghaisas SD, et al. Effect of turmeric oil and turmeric oleoresin on cytogenetic damage in patients suffering from oral submucous fibrosis. Cancer Lett. 1997;116:265–9. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patil PG, Parkhedkar RD. New graft-stabilizing clip as a treatment adjunct for oral submucous fibrosis. J Prosthet Dent. 2009;102:191–2. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(09)60146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]