Abstract

Owing to the inability of self-replacement by a damaged myocardium, alternative strategies to heart transplantation have been explored within the last decades and cardiac tissue engineering/regenerative medicine is among the present challenges in biomedical research. Hopefully, several studies witness the constant extension of the toolbox available to engineer a fully functional, contractile, and robust cardiac tissue using different combinations of cells, template bioscaffolds, and biophysical stimuli obtained by the use of specific bioreactors. Mechanical forces influence the growth and shape of every tissue in our body generating changes in intracellular biochemistry and gene expression. That is why bioreactors play a central role in the task of regenerating a complex tissue such as the myocardium. In the last fifteen years a large number of dynamic culture devices have been developed and many results have been collected. The aim of this brief review is to resume in a single streamlined paper the state of the art in this field.

1. Introduction

Bioengineered tissue is a potential solution for the replacement of a damaged failing heart [1, 2]. In this respect, the ability to emulate in a cell culture the physical cues involved in the physiological development of a normal cardiac tissue is a key for a successful application of tissue engineering in regenerative medicine. Although bioengineered tissues such as skin [3] and bone [4] are already a clinical option available to patients, cardiac muscle tissue engineering is a present challenge in biomedical research—albeit several studies witness a definite advancement in this field [5].

“Cell therapy,” that is, the direct injection of cell suspensions in damaged cardiac areas has a documented potential for cardiovascular repair [6]. Obviously, which type of cells has to be used to generate an artificial heart tissue represents a relevant issue, since it heavily impacts the final properties of a graft. As a matter of fact, cells should at least be highly viable, able of electromechanical integration with the resident healthy cardiomyocytes, and possibly histocompatible. In this respect, the effectiveness of grafting stem cells (SCs) into a damaged heart is nowadays more than just a proof of principle [7–10]. It is well established that embryonic SCs (ESCs) are able to generate cardiomyocytes [11]. However, ethical and technical issues (risk of teratoma following transplantation of ESC-derived cardiomyocytes [12]) limit their clinical potential. The ability to generate induced pluripotent SCs (iPSCs) [13] provides an approach for the generation of autologous grafts. Moreover iPSCs appear able of cardiomyogenic differentiation [14]. Their main limitations for the clinical use are the time requirement for the reprogramming procedure and, again, the need to ensure that they are nontumorigenic. Resident cardiac SCs are another promising phenotype that can be isolated from identifiable cardiac niches and expanded ex vivo [15]. However, the high invasiveness of the withdrawal technique limits their clinical application. Thus, recently adult mesenchymal SCs (MSCs) have been extensively investigated, aiming to their use in biological constructs for cardiac repair, due to the relative ease and safeness of their procurement—mainly from bone marrow and adipose tissue—also in humans. [16–18]. Irrespective of the phenotype, cell therapy is however hampered by the poor survival of injected cells: in fact, most of them die shortly after grafting into the injured heart where hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, loss of survival signals, and inflammation are all responsible for contributing to a hostile environment [19–21]. Engineering a pseudotissue in vitro for subsequent engraftment in vivo was thus proposed as a more suitable approach than the direct cell injection. In this case, a scaffold should provide a structured environment with tissue-specific mechanical properties and the ability to integrate with surrounding tissue [22, 23]. Biomaterials used for scaffold fabrication include biological molecules (e.g., alginate, collagen, fibrin, and hyaluronan) and biomimetic synthetic polymers (e.g., polylactic and polyglycolic acids and their copolymers, polycaprolactone) where a specific supramolecular architecture is designed to sustain the differentiation and functional organization of the seeded cells [24–31].

The appropriate elastic modulus and a 3D environment of the scaffold are preferred to drive the differentiation of SCs into cardiac muscle tissue [32–34]. Cell expansion and differentiation in culture, to develop a cardiac pseudotissue ex vivo, will take advantage of using a bioreactor, to guarantee environmental conditions and biophysical parameters able to induce, sustain and enhance the development of engineered cardiac graft. Introduction of bioreactors in tissue engineering was driven by the need to apply defined culture regimes [35] and they can be defined as any apparatus able to provide in vitro a favorable physicochemical environment to promote physiological conditions for cell/tissue growth. In a general way, they share some common features, such as maintaining the desired concentration of gases and nutrients in the culture medium, establishing a uniform distribution of cells on a 3D scaffold, and exposing the developing tissue to physical stimuli according to the functional requirements of the tissue to be engineered (Figure 1) [36].

Figure 1.

Schematic description of the common features of bioreactors for tissue engineering.

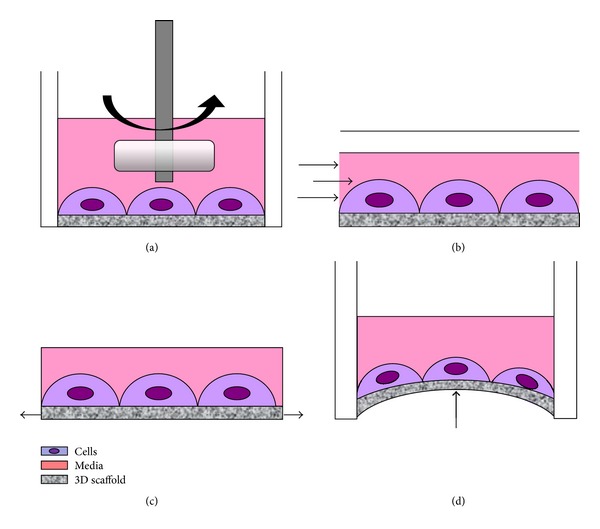

In the last decade, the bioreactor technology in the field of cardiac tissue engineering evolved from very simple apparatus, such as spinner flask/rotating vessel (Figure 2(a)), to more complicated systems, such as perfusion bioreactors (Figure 2(b)) and dynamic loading chambers (Figures 2(c) and 2(d)). Older devices were intended for improving nutrient and gas distribution by mixing media without providing full control of culture parameters. These instruments became more and more sophisticated in order to apply defined physical stimuli [unidirectional or biaxial (cyclic) deformation, compression, stretch, perfusion, electrical force, etc.] appropriate to act on cell differentiation. A number of distinct configurations are nowadays available for specific purposes. Since the specific feature of cardiac muscle is the coordinated electromechanical coupling among its cells we here focus on an update on bioreactors used for engineering cardiac pseudotissue, reporting the approaches described in this field to date.

Figure 2.

Schematic description of significant physical stimuli applied to cells growing in a bioreactor. A spinner flask/rotating vessel (a) improves nutrient and gas distribution by mixing culture media. Perfusion-based bioreactors (b) promote cell proliferation and matrix production via pulsatile flow and shear forces. Dynamic loading chambers (c, d) are intended to apply defined mechanical forces such as (cyclic) unidirectional (c) or biaxial (d) deformation to generate a strain.

2. Bioreactors for Cardiac Tissue Engineering

The application of specific physical stimuli in a tailored bioreactor emerged as an appropriate strategy to obtain a bioengineered cardiac tissue, where mechanotransduction is known to play a significant role [37]. The initial evidence of effectiveness of mechanostimulation protocols in cardiac tissue engineering dates back to the second half of the nineties, when Vandenburgh et al. [38] showed that unidirectional mechanical stretch initiated in vitro a number of morphological alterations in a confluent cardiomyocyte population which were similar to those occurring during in vivo heart growth. A few years later, culturing engineered tissue under mixing of medium in a culture vessel was proven to help induce 3D constructs with cardiac-specific structural and electrophysiological properties [39, 40].

Since then a number of increasingly sophisticated approaches followed, and the purpose of this review is their listing according to the preferred approach endorsed for the application of the mechanostimulation protocol, that is, either the mechanical strain or the perfusion flow (see also Table 1).

Table 1.

Bioreactor technology for cardiac tissue engineering.

| Authors | Year | Cell source | Scaffold | Biophysical stimulus | Apparatus | Biological effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vandenburgh et al. [38] | 1996 | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes | Collagen-coated silicon membranes | Unidirectional stretch | Mechanical cell stimulator | Increased foetal β- and adult α-MHC isoforms |

|

| ||||||

| Carrier et al. [40] | 1999 | Neonatal rat and embryonic chick cardiomyocytes | PGA | Perfusion by medium mixing | Rotating vessel microgravity bioreactor | Expression of cardiac-specific proteins and better ultrastructural organization |

|

| ||||||

| Fink et al. [41] | 2000 | Neonatal rat and embryonic chick cardiomyocytes | Collagen I | Unidirectional stretch | Custom stretching device | Improved organization of cardiomyocytes; hypertrophy |

|

| ||||||

| Akhyari et al. [42] | 2002 | Human heart cells (ventricular biopsy) | Gelfoam gelatine | Cyclic stretch | Biostretch | Enhancement of collagen matrix formation and organization |

|

| ||||||

| Zimmermann et al. [43] | 2002 | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes | Collagen | Unidirectional cyclic stretch | Custom stretching device | Highly organized sarcomeres; adherens junctions, gap junctions, and desmosomes; well-developed T-tubular network; contractile characteristics of native myocardium |

|

| ||||||

| Iijima et al. [44] | 2003 | Rat cardiomyocytes and skeletal myocytes | Collagen-coated silicon membranes | Cyclic stretch | Mechanical cell stimulator | Expression of cardiac-specific proteins: cardiac troponin T, cadherin, and connexin 43 |

|

| ||||||

| Radisic et al. [45] | 2004 | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes | Ultrafoam collagen | Perfusion | Custom device | Thick, compact, and contractile cardiac constructs; higher cell viability |

|

| ||||||

| Boublik et al. [46] | 2005 | Rat heart cells | Hyaluronan | Cyclic stretch | Biostretch | Hybrid cardiac constructs with mechanical properties suitable for in vitro loading studies and in vivo implantation |

|

| ||||||

| Feng et al. [47] | 2005 | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes | Silicon membranes | Mechanical stretch (+ electric field stimulation) | Custom stretching device | In vitro simulation of the electrical and mechanical responses of the myocardium in vivo |

|

| ||||||

| Figallo et al. [48] | 2007 | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes and human ESCs | Collagen-coated glass | Perfusion | Custom microarray (MBA) | Increased smooth muscle actin and cell density |

|

| ||||||

| Brown et al. [49] | 2008 | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes | Ultrafoam collagen | Perfusion | Custom device | Enhancement of contractile properties |

|

| ||||||

| Gwak et al. [50] | 2008 | Mouse ESC-derived cardiomyocytes | PLCL and PLGA | Cyclic stretch | Custom device | Enhancement of cardiac-specific gene expression: α-MHC, α-actin |

|

| ||||||

| Shimko and Claycomb [51] | 2008 | Mouse ESC-derived cardiomyocytes | Collagen I/fibronectin | Unidirectional cyclic stretch | Custom stretching device | Increased gene expression at 3 Hz cyclical stretch |

|

| ||||||

| Ge et al. [52] | 2009 | Rat BM-MSCs | Silicon membrane | Biaxial mechanical stretch | Custom stretching device | Expression of α-actin, connexion 43, α-MHC, and troponin I |

|

| ||||||

| Barash et al. [53] | 2010 | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes | Alginate | Perfusion (+ electric field stimulation) | Custom device | Promotion of cell elongation and striation and enhancement of the expression level of connexin-43 |

|

| ||||||

| Hosseinkhani et al. [54] | 2010 | Rat CSCs | Collagen-PGA nanofibers | Perfusion | Custom device | Significant enhancement of cell proliferation |

|

| ||||||

| Salameh et al. [55] | 2010 | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes | Gelatin-coated silicone membrane | Biaxial mechanical stretch | Flexcell Tension System FX-4000 | Self-organization of cardiomyocytes, enhanced connexin-43 expression and distribution at the cell poles |

|

| ||||||

| Galie and Stegemann [56] | 2011 | Rat cardiac fibroblasts | Collagen hydrogel | Mechanical stretch and interstitial flow | Custom device | Cell viability |

|

| ||||||

| Hollweck et al. [57] | 2011 | Human UCMSCs | PTFE | Biaxial mechanical stretch | Custom device | Confluent cellular coating without damage on the cell surface |

|

| ||||||

| Kenar et al. [58] | 2011 | Human MSCs (Wharton's Jelly) | PHBV-PLLA and PGS | Perfusion | Custom device | Enhanced cell viability, uniform cell distribution and alignment |

|

| ||||||

| Kensah et al. [59] | 2011 | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes | Collagen I/Matrigel | Cyclic stretch and perfusion (+ electric field stimulation) | Custom device | Cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, shift of myosin heavy chain expression from the alpha to beta isoform |

|

| ||||||

| Maul et al. [60] | 2011 | Rat MSCs | Collagen-coated silicon membranes | Biaxial mechanical stretch (∧) or laminar shear stress (∗) or cyclic hydrostatic pressure (#) | (∧) Flexcell Tension System FX-4000 or (∗) Streamer shear stress Flexcell device or (#) custom device | Systematic examination of the effects of mechanical stimulation on MSCs |

|

| ||||||

| Tulloch et al. [61] | 2011 | Human ESCs and human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes | Collagen I | Cyclic stress | Flexcell Tension System FX-4000 | Cardiomyocytes hypertrophy and proliferation |

|

| ||||||

| Govoni et al. [62] | 2012 | Rat MSCs | Hyaluronan | Unidirectional cyclic stretch | Custom device | Cell multilayer organization and invasion of the 3D mesh of the scaffold, muscle protein expression |

|

| ||||||

| Maidhof et al. [63] | 2012 | Rat heart cells | PGS | Perfusion (+ electric field stimulation) | Custom device | Improvement of DNA content, cell distribution throughout the scaffold thickness, cardiac protein expression, and cell morphology |

|

| ||||||

| Shachar et al. [64] | 2012 | Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes | RGD-attached alginate | Compression and shear stress | Custom device | Increased connexin-43, α-actin, and N-cadherin |

2.1. Mechanical Strain

Six days of unidirectional stretch of engineered heart tissue (EHT)—made out of neonatal rat or embryonic chick cardiomyocytes mixed in collagen I—in a custom-made device improved their cellular organization and increased atrial natriuretic factor (ANF) mRNA and α-sarcomeric actin compared to unstretched controls [41]. The force of contraction of this EHT was up to fourfold higher after mechanical stimulation and the protocol was proposed as an in vitro model allowing morphological, molecular, and functional consequences of stretch to be studied under defined conditions. This same German research group developed shortly after [43] an improved technique to obtain circular EHT resulting in better technical feasibility, tissue homogeneity, and cardiomyocyte differentiation. After seven days of unidirectional cyclic stretch (10%; 2 Hz), the EHT displayed structural and functional features of a native differentiated myocardium and were proposed as a promising material for in vitro studies of cardiac function and tissue replacement therapy.

In the same year Akhyari et al. [42] proved that a mechanical stretch regimen—applied via the Biostretch apparatus (ICCT Technologies, Markham, ON, Canada) presented by Liu et al. [65] (mechanical properties and remodeling of hybrid cardiac constructs made from heart cells, fibrin, and a biodegradable, elastomeric knitted fabric were tested using the same apparatus by Boublik et al. in 2005 [46]) to human heart cells that were seeded on a 3D gelatin scaffold (Gelfoam sponge, Pharmacia & Upjohn Co., Kalamazoo, MI, USA)—improves the formation and enhances the strength of a bioengineered muscle graft. Dynamic stimulation of cells/gelatine constructs during 14 days (80 cycles/min with a 20% deformation of the initial length) generated a marked increase in cell proliferation, improved spatial cell distribution throughout the scaffold, and markedly increased the total amount of newly synthesized collagen matrix with fibres aligned in parallel to the axis of stress.

Iijima et al. [44] showed that mechanical load on skeletal muscle-derived cells is important for their transdifferentiation into the cardiac phenotype since passive cyclic stretch (60 cycles/min) of skeletal muscle-derived cells cocultured on silicone dishes with cardiomyocytes entirely restored the inhibition of their spontaneous beating produced with 5 μM nifedipine.

At this stage the application of a mechanostimulation protocol on terminally differentiated cells entered the age of majority: Zimmermann et al. [66, 67] provided the evidence that contractile cardiac tissue grafts, generated with the aid of mechanical strain in vitro, can survive after implantation and can support contractile function of infarcted rat hearts.

Since stem cells have entered the arena of regenerative medicine, the use of mechanostimulation protocols to address their cardiac differentiation was witnessed in several scientific reports.

In 2008, Gwak et al. [50] investigated whether cyclic mechanical strain promotes cardiomyogenesis in mouse embryonic stem cell (ESCs) seeded on the elastic polymer poly(lactide-co-caprolactone) (PLCL). Mechanical load was applied in a custom-made bioreactor, previously described by Kim and Mooney [68]. The scaffolds were subjected to cyclic strain (10%; 1 Hz) in a standard incubator for 2 weeks. Mechanical load promoted cardiac-specific gene expression and tests in vivo showed a significant increase of grafting efficiency and the cardiomyogenic potential of the implanted cells.

In the same year, Shimko and Claycomb [51] used a bioreactor where ring-shaped constructs were stretched via a computer-controlled mechanism to explore the effects of long-term mechanical loading on mouse ESCs-derived cardiomyocytes. The cells, embedded in a 3D gelatinous scaffold (collagen type I and fibronectin), underwent cyclical mechanical stimulation (10%; 1, 2, and 3 Hz) for 3 days. This study demonstrated that ESCs-derived cardiomyocytes are actively responding to physical cues from the environment: α-cardiac actin, α-skeletal actin, α-myosin heavy chain (MHC), and β-MHC were all upregulated at 3 Hz.

In 2009, Ge et al. [52] investigated cardiomyocyte differentiation potential of rat bone marrow-mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) treating these cells by applying 4% strain at 1 Hz. Biaxial mechanical stress, provided with a custom device previously described by Banes et al. [69], induced in BM-MSCs the expression of cardiomyocyte-specific genes including α-actin, connexin 43, α-MHC, and troponin I.

During the most recent years, the application of mechanical cyclic strain to 2D cell cultures was often obtained using the Flexcell Strain Unit (Flexcell Int., Hillsborough, NC, USA), a commercial device where vacuum pressure applied to flexible-bottomed silicone culture plates produces uniaxial or biaxial deformation.

In 2010, Salameh et al. [55] examined with this device whether cyclic mechanical stretch can affect localization of gap junctions with regard to the cell axis. Neonatal rat cardiomyocytes seeded on gelatin-coated membranes were stimulated (1 Hz; 0, 10, and 20% elongation) for 24 or 48 hours. Cyclic mechanical stretch (24 hour, 10%) induced elongation of the cardiomyocytes and orientation toward the stretch direction. Moreover, the distribution of connexin 43 and N-cadherin was accentuated at the cell poles. A significant increase in the transcription factors activator protein 1 and cAMP response element-binding protein was also scored.

In 2011, Maul et al. [60] used the Flexcell Unit for the systematic analysis of mechanical stimulation on SCs differentiation. Experiments were conducted using subconfluent MSCs for 5 days and demonstrated significant effects on morphology and proliferation, defining thresholds of cyclic stretch that potentiate (smooth) muscle protein expression. This systematic examination of the effects of mechanical stimulation on MSCs has implications for the understanding of SCs biology, as well as potential bioreactor designs for tissue engineering and cell therapy applications.

In the same year, Tulloch et al. [61] used human ESCs and induced pluripotent SC-derived cardiomyocytes in a 3-dimensional collagen matrix, to show that uniaxial mechanical stress conditioning—imparted with the Flexcell Unit—promotes a twofold increase of cardiomyocyte proliferation, matrix fiber alignment, and enhanced myofibrillogenesis and sarcomeric banding. Addition of endothelial cells enhanced cardiomyocyte proliferation, and addition of stromal supporting cells enhanced formation of vessel-like structures. These optimized human cardiac tissue constructs generate Starling curves, developing active force in response to increased resting length. Moreover, when transplanted onto hearts of athymic rats, the human myocardium survived and formed grafts closely apposed to host myocardium and containing human microvessels perfused by the host coronary circulation. The authors concluded that mechanical load and vascular cell coculture control cardiomyocyte proliferation, hypertrophy, and architecture of engineered human myocardium. Such constructs were proposed for studying human cardiac development as well as for regenerative therapy.

To test the mechanical integrity and functionality of SCs engineered constructs prior to implantation, Hollweck et al. [57] proposed in 2011 a pulsatile bioreactor mimicking myocardial contraction. Mesenchymal stem cells derived from umbilical cord tissue (UCMSC) were colonized on titanium-coated polytetrafluorethylene (PFTE) scaffolds and underwent sinusoidal pulsation. Experiments to determine the adherence rate and morphology of UCMSC after mechanical loading showed an almost confluent cellular coating without damage on the cell surface and the bioreactor appeared an adequate tool for the mechanical stress of seeded scaffolds in order to precondition cardiac tissue engineered constructs in vitro.

All this evidence in the literature demonstrates the effect of cyclic mechanical stretch in maintaining, or addressing, a muscle phenotype. However, all the presented results were obtained using technical approaches useful for the experimental collection of proofs of principle but unlikely suitable for application in clinical protocols for regenerative medicine. Focusing on this issue, our group [62] designed a reliable innovative bioreactor, acting as a stand-alone cell culture incubator, easy to operate and effective in addressing rat MSCs seeded onto a 3D bioreabsorbable scaffold, toward a muscle phenotype via the transfer of a controlled and highly reproducible cyclic deformation. Electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and biochemical analysis of the pseudotissue constructs obtained after 1 week of cyclic mechanical stretch (10%; 1.6 Hz) showed cell multilayer organization and invasion of the 3D mesh of the scaffold. In addition they expressed typical markers of the muscle phenotype. This device is thus proposed as a prototypal instrument to obtain, using good manufacturing procedures, pseudotissue constructs to test in cardiovascular regenerative medicine.

2.2. Perfusion Bioreactors

Bioreactors used in cardiac tissue regeneration include devices where a mechanical load is transferred to the cells by culture medium routed (pulsatile flow, shear stress) through the construct with a perfusion loop.

In 2004, Radisic et al. [45] designed an in vitro culture system maintaining efficient oxygen supply to neonatal rat cardiomyocytes suspended in Matrigel and cultured on collagen sponges for 7 days with interstitial flow of medium. Constructs were assessed at timed intervals with respect to cell number, distribution, viability, metabolic activity, cell cycle, presence of contractile proteins (sarcomeric α-actin, troponin I, and tropomyosin), and contractile function in response to electrical stimulation. Perfusion resulted in higher cell viability and, in response to electrical stimulation, perfused constructs contracted synchronously and had a lower excitation threshold than controls.

A microbioreactor array, fabricated using soft lithography and containing twelve independent microbioreactors perfused with culture medium, was presented by Figallo et al. [48] in 2007. This device enabled cultivation of cells either attached to substrates or encapsulated in hydrogels, at variable levels of hydrodynamic shear, and with automated image analysis of the expression of cell differentiation markers. This configuration was validated using primary rat cardiomyocytes and human ESCs evaluating correlations between the expression of smooth muscle actin and cell density for three different flow configurations.

Brown et al. [49] used a perfusion bioreactor suggesting that the provision of pulsatile interstitial medium flow to an engineered cardiac patch would result in enhanced tissue assembly by way of mechanical conditioning and improved mass transport. Cardiac patches, obtained by the seeding of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes onto Ultrafoam collagen hemostat discs, were cultured for 5 days subjected to two different overall flow rates (1.50 mL/min or 0.32 mL/min) at 1 Hz. The data reported in this study show that cultivation under pulsatile flow has beneficial effects on contractile properties and promotes cell hypertrophy.

In 2009, Hosseinkhani et al. [54] combined micro- and nanoscale technologies to fabricate a 3D collagen-poly (glycolic acid) (PGA) cell substrate for tissue engineering purposes where rat cardiac SCs (CSCs) were seeded and perfused to give a constant laminar flow of medium into the cell constructs to enhance their attachment and proliferation. Results demonstrated that this perfusion bioreactor improved the proliferation of CSCs in vitro compared with standard culture methods.

More recently, Kenar et al. [58] designed and developed a myocardial 3D patch formed by a microfibrous mat housing MSCs from human umbilical cord matrix (Wharton's Jelly) aligned in parallel to each other as they are in native myocardium. The 3D construct was dynamically cultured in a bioreactor by transiently perfusing cell medium through the macroporous tubing of the mat. After two weeks in the bioreactor, perfused cultures demonstrated enhanced cell viability, uniform cell distribution, and alignment due to nutrient provision from inside the 3D structure.

This brief listing of flow-controlling devices for tissue cardiac engineering ends mentioning that in the same manuscript published by Maul et al. [60] in 2011, in addition to the use of the Flexcell Unit for the systematic analysis of mechanical stimulation on SCs differentiation (see above), the authors also evaluated on MSCs the impact of laminar shear stress—applied via the Streamer shear stress Flexcell device—that increased endothelial cell protein expression in a cell-contact-dependent manner.

2.3. Hybrid Bioreactors

In a limited number of cases, the research in the field proposed hybrid devices, where more than a single type of mechanical stress is applied to cultured cells addressed toward the cardiac phenotype. As an example, electric and mechanical stimuli were occasionally applied to SCs on the hypothesis that the coupling of these stimuli might produce a synergy for their differentiation process.

Feng et al. [47] presented the first bioreactor system where cardiomyocytes from rat embryos were seeded on collagen-coated silicon membranes and cultured up to 4 days under electromechanical stimulation. Their results emphasized the importance of electrotensile forces on the augmentation of the contractile force in a “cardiac tissue equivalent.”

Barash et al. [53] used a custom-made electrical stimulator, integrated into a perfusion bioreactor originally described in 2006 by Dvir et al. [70], with the purpose of producing thick and functional cardiac patches. Rat ventricular cardiomyocytes were seeded on porous alginate scaffolds and subjected to a homogenous fluid flow regime with electrical stimulation. Results showed that the cultivation in this bioreactor for 4 days under perfusion and continuous electrical stimulus promoted cell elongation and striation. Immunostaining and western blotting analysis demonstrated that the expression level of connexin 43 was enhanced.

In 2011, Galie and Stegemann [56] validated a device where simultaneous mechanical and fluidic stress was applied to a 3D cell construct. Cardiac fibroblasts were suspended in a collagen type I gel to obtain a 3D cell construct and subjected to cyclic strain (5%; 1 Hz) and interstitial flow (10 mL/min). Cell viability was certified after 5 days in bioreactor under the application of these stimuli. This simple bioreactor system was thus proposed to model tissues such as the myocardium, which experiences interstitial fluid flow from perfusion through the extracellular matrix as well as cyclic strain from the systole—diastole cycle of the heart.

Kensah et al. [59] proposed in 2011 a multimodal bioreactor for mechanical stimulation and real-time direct measurement of contraction forces under continuous sterile culture conditions. The bioreactor's transparent cultivation chamber allows for microscopic assessment of tissue development. Additional functions include electric pacing of tissues, as well as the possibility to perfuse the central cultivation chamber allowing for continuous medium exchange and/or controlled addition of pharmacologically active agents. A functional bioartificial cardiac tissue was generated from rat cardiomyocytes in the bioreactor, where cyclic stretch induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and moderate increase in systolic force. Thus, this bioreactor is proposed as a tool for monitoring tissue development, and ultimately, optimizing SCs-based tissue replacement strategies in regenerative medicine.

Recently, Maidhof et al. [63] asserted that fixing the cell constructs in place for perfusion culture is a severe limitation. Thus, they proposed the design of a bioreactor to deliver simultaneous culture medium perfusion and electrical stimulation during the culture of engineered cardiac constructs free of external fixation. Neonatal rat heart cells were seeded onto channeled microporous elastomer poly(glycerol sebacate) (PGS) scaffolds and the neoformed pseudotissues were stimulated in the bioreactor for eight days. This dynamic culture protocol demonstrated significant improvement of DNA contents in the cell constructs, homogeneous cell distribution throughout the scaffold thickness, enhancement of cardiac protein expression (such as cardiac troponin T and connexin 43) and better cell morphology and overall tissue organization than observed in control group. Although cardiac cells did not form uniformly interconnected tissue after eight days of stimulation in the bioreactor, the results obtained in this study indicated that simultaneous perfusion and electric stimulation enhanced the development of engineered cardiac tissue. Thus, this device could be a relevant tool for cardiac repair in vitro studies and to understand the effective presence of a synergistic effect between perfusion and electric stimuli.

Usually, compression stimulus was extensively used for bone and cartilage tissue engineering [71–73]; however the favourable effect of mechanical compression was successfully certified in a cardiac tissue engineering protocol.

In particular, Shachar et al. [64] investigated how mechanical compression stimulus, combined with fluid shear stress provided by medium perfusion, could lead to the formation of a cardiac muscle tissue in vitro. Neonatal rat cardiac cells were seeded in Arginine-Glycine-Aspartate- (RGD-) attached alginate scaffolds and cultivated for 4 days in a bioreactor for compression and fluid flow stimulation. Two types of compression—intermittent (daily short-term 30 minutes) and continuous—were investigated. Upon application of the “intermittent compression” protocol, western blot showed enhancement of connexin 43, α-actinin, and N-cadherin expression.

3. Conclusions

Bioreactors appear as a key factor for a successful application of tissue engineering principles in cardiac regenerative medicine, where state-of-the-art mechanostimulation protocols have definitely proven to control cell proliferation, differentiation, and electrical coupling in engineered 3D cardiac tissue. A take-home message from this review of the current literature is that perfusion-based bioreactors are to be preferred when, for example, the cell function of interest is electively activated by shear stress, such as in the case of endothelial progenitor cells; when hydrogel/non-elastic scaffolds—which cannot be stretched by mechanical forces—are in use; or when scaffold nutrient diffusion has to be increased by a sustained flow. On the other hand, bioreactors producing mechanical deformation are more suitable with an elastomeric scaffold, where a coupled electromechanical stimulation appears effective in promoting elongation, striation, and acquisition of contractile force by the stretched cells.

Another issue emerging here is that the translation of these models into clinical products is not just around the corner. Rather than a scientific challenge, regulatory and commercial issues slow down the pace. Identifying a roadmap to drive this transition is an integral part of this challenge [74] where the compliance with regulatory guidelines and a robust and cost-effective approach have to match the already available encouraging proofs of principle. Governmental agencies in healthcare and stakeholders, together with clinical research societies and ethics committees, are now responsible for releasing guidelines and resources for the advancement expected by patients.

References

- 1.Alcon A, Cagavi Bozkulak E, Qyang Y. Regenerating functional heart tissue for myocardial repair. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2012;69(16):2635–2656. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0942-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy SV, Atala A. Organ engineering—combining stem cells, biomaterials, and bioreactors to produce bioengineered organs for transplantation. Bioessays. 2013;35(3):163–172. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lei P, You H, Andreadis ST. Bioengineered skin substitutes. Organ Regeneration: Methods in Molecular Biology. 2013;1001:267–278. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-363-3_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panetta NJ, Gupta DM, Longaker MT. Bone regeneration and repair. Current Stem Cell Research and Therapy. 2010;5(2):122–128. doi: 10.2174/157488810791268618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang F, Guan J. Cellular cardiomyoplasty and cardiac tissue engineering for myocardial therapy. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2010;62(7-8):784–797. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vono R, Spinetti G, Gubernator M, Madeddu P. What’s new in regenerative medicine: split up of the mesenchymal stem cell family promises new hope for cardiovascular repair. Journal of Cardiovascular Translational Research. 2012;5(5):689–699. doi: 10.1007/s12265-012-9395-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cashman T, Gouon-Evans V, Costa K. Mesenchymal stem cells for cardiac therapy: practical challenges and potential mechanisms. Stem Cell Reviews and Reports. 2013;9(3):254–265. doi: 10.1007/s12015-012-9375-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henning RJ. Stem cells in cardiac repair. Future Cardiology. 2011;7(1):99–117. doi: 10.2217/fca.10.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Le Huu A, Prakash S, Shum-Tim D. Cellular cardiomyoplasty: current state of the field. Regenerative Medicine. 2012;7(4):571–582. doi: 10.2217/rme.12.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tongers J, Losordo DW, Landmesser U. Stem and progenitor cell-based therapy in ischaemic heart disease: promise, uncertainties, and challenges. European Heart Journal. 2011;32(10):1197–1206. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doetschman TC, Eistetter H, Katz M, Schmidt W, Kemler R. The in vitro development of blastocyst-derived embryonic stem cell lines: formation of visceral yolk sac, blood islands and myocardium. Journal of Embryology and Experimental Morphology. 1985;87:27–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nussbaum J, Minami E, Laflamme MA, et al. Transplantation of undifferentiated murine embryonic stem cells in the heart: teratoma formation and immune response. FASEB Journal. 2007;21(7):1345–1357. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6769com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126(4):663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mauritz C, Schwanke K, Reppel M, et al. Generation of functional murine cardiac myocytes from induced pluripotent stem cells. Circulation. 2008;118(5):507–517. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.778795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beltrami AP, Barlucchi L, Torella D, et al. Adult cardiac stem cells are multipotent and support myocardial regeneration. Cell. 2003;114(6):763–776. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00687-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shim WSN, Jiang S, Wong P, et al. Ex vivo differentiation of human adult bone marrow stem cells into cardiomyocyte-like cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2004;324(2):481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.09.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang W, Lim S, Song BW, et al. Phorbol myristate acetate differentiates human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells into functional cardiogenic cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2012;424(4):740–746. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasini A, Bonafè F, Govoni M, et al. Epigenetic signature of early cardiac regulatory genes in native human adipose-derived stem cells. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s12013-013-9610-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jakob P, Landmesser U. Current status of cell-based therapy for heart failure. Current Heart Failure Reports. 2013;10(2):165–176. doi: 10.1007/s11897-013-0134-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee J, Terracciano CM. Cell therapy for cardiac repair. The British Medical Bulletin. 2010;94(1):65–80. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldq005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malliaras K, Marbán E. Cardiac cell therapy: where weve been, where we are, and where we should be headed. The British Medical Bulletin. 2011;98(1):161–185. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldr018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sekine H, Shimizu T, Okano T. Myocardial tissue engineering: toward a bioartificial pump. Cell and Tissue Research. 2012;347(3):775–782. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tee R, Lokmic Z, Morrison WA, Dilley RJ. Strategies in cardiac tissue engineering. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery. 2010;80(10):683–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ceccaldi C, Fullana SG, Alfarano C, et al. Alginate scaffolds for mesenchymal stem cell cardiac therapy: influence of alginate composition. Cell Transplantation. 2012;21(9):1969–1984. doi: 10.3727/096368912X647252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasquinelli G, Orrico C, Foroni L, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell interaction with a non-woven hyaluronan-based scaffold suitable for tissue repair. Journal of Anatomy. 2008;213(5):520–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00974.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muscari C, Bonafè F, Martin-Suarez S, et al. Restored perfusion and reduced inflammation in the infarcted heart after grafting stem cells with a hyaluronan-based scaffold. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2013;17(4):518–530. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fiumana E, Pasquinelli G, Foroni L, et al. Localization of mesenchymal stem cells grafted with a hyaluronan-based scaffold in the infarcted heart. Journal of Surgical Research. 2013;179(1):e21–e29. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gualandi C, Soccio M, Govoni M, et al. Poly(butylene/diethylene glycol succinate) multiblock copolyester as a candidate biomaterial for soft tissue engineering: solid-state properties, degradability, and biocompatibility. Journal of Bioactive and Compatible Polymers. 2012;27(3):244–264. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shapira K, Dikovsky D, Habib M, Gepstein L, Seliktar D. Hydrogels for cardiac tissue regeneration. Bio-Medical Materials and Engineering. 2008;18(4-5):309–314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeong WY, Sudarmadji N, Yu HY, et al. Porous polycaprolactone scaffold for cardiac tissue engineering fabricated by selective laser sintering. Acta Biomaterialia. 2010;6(6):2028–2034. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karam JP, Muscari C, Montero-Menei CN. Combining adult stem cells and polymeric devices for tissue engineering in infarcted myocardium. Biomaterials. 2012;33(23):5683–5695. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Santis G, Lennon AB, Boschetti F, Verhegghe B, Verdonck P, Prendergast PJ. How can cells sense the elasticity of a substrate? An analysis using a cell tensegrity model. European Cells & Materials. 2011;22:202–213. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v022a16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engelmayr GC, Jr., Cheng M, Bettinger CJ, Borenstein JT, Langer R, Freed LE. Accordion-like honeycombs for tissue engineering of cardiac anisotropy. Nature Materials. 2008;7(12):1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/nmat2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126(4):677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen HC, Hu YC. Bioreactors for tissue engineering. Biotechnology Letters. 2006;28(18):1415–1423. doi: 10.1007/s10529-006-9111-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grayson WL, Martens TP, Eng GM, Radisic M, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Biomimetic approach to tissue engineering. Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2009;20(6):665–673. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi K, Kakimoto Y, Toda K, Naruse K. Mechanobiology in cardiac physiology and diseases. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2013;17(2):225–232. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vandenburgh HH, Solerssi R, Shansky J, Adams JW, Henderson SA. Mechanical stimulation of organogenic cardiomyocyte growth in vitro . The American Journal of Physiology. 1996;270(5):C1284–C1292. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.270.5.C1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bursac N, Papadaki M, Cohen RJ, et al. Cardiac muscle tissue engineering: toward an in vitro model for electrophysiological studies. The American Journal of Physiology. 1999;277(2, part 2):H433–H444. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.2.H433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carrier RL, Papadaki M, Rupnick M, et al. Cardiac tissue engineering: cell seeding, cultivation parameters, and tissue construct characterization. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 1999;64(5):580–589. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0290(19990905)64:5<580::aid-bit8>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fink C, Ergün S, Kralisch D, Remmers U, Weil J, Eschenhagen T. Chronic stretch of engineered heart tissue induces hypertrophy and functional improvement. FASEB Journal. 2000;14(5):669–679. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.14.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Akhyari P, Fedak PWM, Weisel RD, et al. Mechanical stretch regimen enhances the formation of bioengineered autologous cardiac muscle grafts. Circulation. 2002;106(12, supplement 1):I137–I142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zimmermann W, Schneiderbanger K, Schubert P, et al. Tissue engineering of a differentiated cardiac muscle construct. Circulation Research. 2002;90(2):223–230. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.103644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iijima Y, Nagai T, Mizukami M, et al. Beating is necessary for transdifferentiation of skeletal muscle-derived cells into cardiomyocytes. The FASEB Journal. 2003;17(10):1361–1363. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1048fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Radisic M, Yang L, Boublik J, et al. Medium perfusion enables engineering of compact and contractile cardiac tissue. The American Journal of Physiology. 2004;286(2):H507–H516. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00171.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boublik J, Park H, Radisic M, et al. Mechanical properties and remodeling of hybrid cardiac constructs made from heart cells, fibrin, and biodegradable, elastomeric knitted fabric. Tissue Engineering. 2005;11(7-8):1122–1132. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Feng Z, Matsumoto T, Nomura Y, Nakamura T. An electro-tensile bioreactor for 3-D culturing of cardiomyocytes. IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine. 2005;24(4):73–79. doi: 10.1109/memb.2005.1463399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Figallo E, Cannizzaro C, Gerecht S, et al. Micro-bioreactor array for controlling cellular microenvironments. Lab on a Chip. 2007;7(6):710–719. doi: 10.1039/b700063d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brown MA, Iyer RK, Radisic M. Pulsatile perfusion bioreactor for cardiac tissue engineering. Biotechnology Progress. 2008;24(4):907–920. doi: 10.1002/btpr.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gwak SJ, Bhang SH, Kim IK, et al. The effect of cyclic strain on embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Biomaterials. 2008;29(7):844–856. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimko VF, Claycomb WC. Effect of mechanical loading on three-dimensional cultures of embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Tissue Engineering A. 2008;14(1):49–58. doi: 10.1089/ten.2007.0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ge D, Liu X, Li L, et al. Chemical and physical stimuli induce cardiomyocyte differentiation from stem cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2009;381(3):317–321. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.01.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barash Y, Dvir T, Tandeitnik P, Ruvinov E, Guterman H, Cohen S. Electric field stimulation integrated into perfusion bioreactor for cardiac tissue engineering. Tissue Engineering C. 2010;16(6):1417–1426. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2010.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hosseinkhani H, Hosseinkhani M, Hattori S, Matsuoka R, Kawaguchi N. Micro and nano-scale in vitro 3D culture system for cardiac stem cells. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research A. 2010;94(1):1–8. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Salameh A, Wustmann A, Karl S, et al. Cyclic mechanical stretch induces cardiomyocyte orientation and polarization of the gap junction protein connexin43. Circulation Research. 2010;106(10):1592–1602. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.214429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Galie PA, Stegemann JP. Simultaneous application of interstitial flow and cyclic mechanical strain to a three-dimensional cell-seeded hydrogel. Tissue Engineering C. 2011;17(5):527–536. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2010.0547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hollweck T, Akra B, Häussler S, et al. A novel pulsatile bioreactor for mechanical stimulation of tissue engineered cardiac constructs. Journal of Functional Biomaterials. 2011;2(3):107–118. doi: 10.3390/jfb2030107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kenar H, Kose GT, Toner M, Kaplan DL, Hasirci V. A 3D aligned microfibrous myocardial tissue construct cultured under transient perfusion. Biomaterials. 2011;32(23):5320–5329. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kensah G, Gruh I, Viering J, et al. A novel miniaturized multimodal bioreactor for continuous in situ assessment of bioartificial cardiac tissue during stimulation and maturation. Tissue Engineering C. 2011;17(4):463–473. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2010.0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Maul TM, Chew DW, Nieponice A, Vorp DA. Mechanical stimuli differentially control stem cell behavior: morphology, proliferation, and differentiation. Biomechanics and Modeling in Mechanobiology. 2011;10(6):939–953. doi: 10.1007/s10237-010-0285-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tulloch NL, Muskheli V, Razumova MV, et al. Growth of engineered human myocardium with mechanical loading and vascular coculture. Circulation Research. 2011;109(1):47–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Govoni M, Lotti F, Biagiotti L, et al. An innovative stand-alone bioreactor for the highly reproducible transfer of cyclic mechanical stretch to stem cells cultured in a 3D scaffold. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. 2012 doi: 10.1002/term.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Maidhof R, Tandon N, Lee EJ, et al. Biomimetic perfusion and electrical stimulation applied in concert improved the assembly of engineered cardiac tissue. Journal of Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine. 2012;6(10):e12–e23. doi: 10.1002/term.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shachar M, Benishti N, Cohen S. Effects of mechanical stimulation induced by compression and medium perfusion on cardiac tissue engineering. Biotechnology Progress. 2012;28(6):1551–1559. doi: 10.1002/btpr.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu M, Montazeri S, Jedlovsky T, et al. Bio-stretch, a computerized cell strain apparatus for three-dimensional organotypic cultures. In Vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology—Animal. 1999;35(2):87–93. doi: 10.1007/s11626-999-0006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zimmermann WH, Melnychenko I, Eschenhagen T. Engineered heart tissue for regeneration of diseased hearts. Biomaterials. 2004;25(9):1639–1647. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00521-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zimmermann WH, Melnychenko I, Wasmeier G, et al. Engineered heart tissue grafts improve systolic and diastolic function in infarcted rat hearts. Nature Medicine. 2006;12(4):452–458. doi: 10.1038/nm1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kim BS, Mooney DJ. Scaffolds for engineering muscle under cyclic mechanical strain conditions. Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 2000;122(3):210–215. doi: 10.1115/1.429651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Banes AJ, Gilbert J, Taylor D, Monbureau O. A new vacuum-operated stress-providing instrument that applies static or variable duration cyclic tension or compression to cells in vitro . Journal of Cell Science. 1985;75(1):35–42. doi: 10.1242/jcs.75.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dvir T, Benishti N, Shachar M, Cohen S. A novel perfusion bioreactor providing a homogenous milieu for tissue regeneration. Tissue Engineering. 2006;12(10):2843–2852. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orr DE, Burg KJL. Design of a modular bioreactor to incorporate both perfusion flow and hydrostatic compression for tissue engineering applications. Annals of Biomedical Engineering. 2008;36(7):1228–1241. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9505-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shahin K, Doran PM. Tissue engineering of cartilage using a mechanobioreactor exerting simultaneous mechanical shear and compression to simulate the rolling action of articular joints. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2012;109(4):1060–1073. doi: 10.1002/bit.24372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang PY, Tsai WB. Modulation of the proliferation and matrix synthesis of chondrocytes by dynamic compression on genipin-crosslinked chitosan/collagen scaffolds. Journal of Biomaterials Science, Polymer Edition. 2013;24(5):507–519. doi: 10.1080/09205063.2012.696310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Martin I, Smith T, Wendt D. Bioreactor-based roadmap for the translation of tissue engineering strategies into clinical products. Trends in Biotechnology. 2009;27(9):495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]