INTRODUCTION

Spiralling healthcare costs and demand, against a backdrop of financial austerity makes healthcare commissioning in England a real challenge. ‘Financial balance’ is a major priority, but, as reinforced by the Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust failures, cost-cutting must not compromise patient safety and experience. Consequently, commissioners have looked to ‘demand management’ as a solution. This refers to methods used to monitor, direct, or regulate patient referrals from primary care to specialist, non-emergency care in hospital. In the UK, GPs act as gatekeepers and define which patients require referral to specialist care. As demand outstrips resources, the volume and appropriateness of these referrals becomes a major concern and much focus has been placed on managing rising demand. Indeed, in 2009, 91% of primary care trusts in England engaged in some form of referral diversion.1 However, the evidential basis for such interventions are lacking.

WHAT HAS BEEN TRIED

Various strategies already tried have targeted primary care, specialist services, or infrastructure.2 These included encouraging ‘internal referrals’ within and between general practices, and task shifting clinical work from clinicians to nurses and other health professionals. Telephone triage systems have been used including large scale initiatives such as NHS Direct. Community-based specialist services, for example, heart failure nurses, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) teams, and dementia teams, and ‘community matrons’ tasked with managing patients with long-term conditions, have been tried with varying success.3

Efforts were also made to empower patients to self-care such as the Expert Patient Programme, as well as de-marketing strategies to encourage the public to use local emergency departments appropriately. Reducing wastage in the system, including non-attendance at clinic appointments by patients, was also examined. Recently, English health providers have also implemented strategies such as the graduated care approach (that is, Kaiser Permanente model), risk stratification tools such as Patients at Risk of Re-hospitalisation (PARR), and the Combined Predictive Model (CPM) and ‘virtual wards’.4 Again, the evidence supporting these approaches are limited.

WHAT IS KNO WN SO FAR

Referral pathway redesign

Many demand-management interventions focus on referral diversion or redesign of the referral pathway such as the use of referral management centres. However, interventions to reduce demand could have detrimental health outcomes. Demand management does not only mean reducing it: where cost-effective health care is underused, demand may need to be encouraged.5 Crucially, attempts at referral management introduce demand-side barriers that worsen access for vulnerable groups and exacerbate health inequalities.6 Referral management should not therefore solely focus on reducing demand, but on ensuring that the right patients receive the right care, at the right time, and care received is right first time.

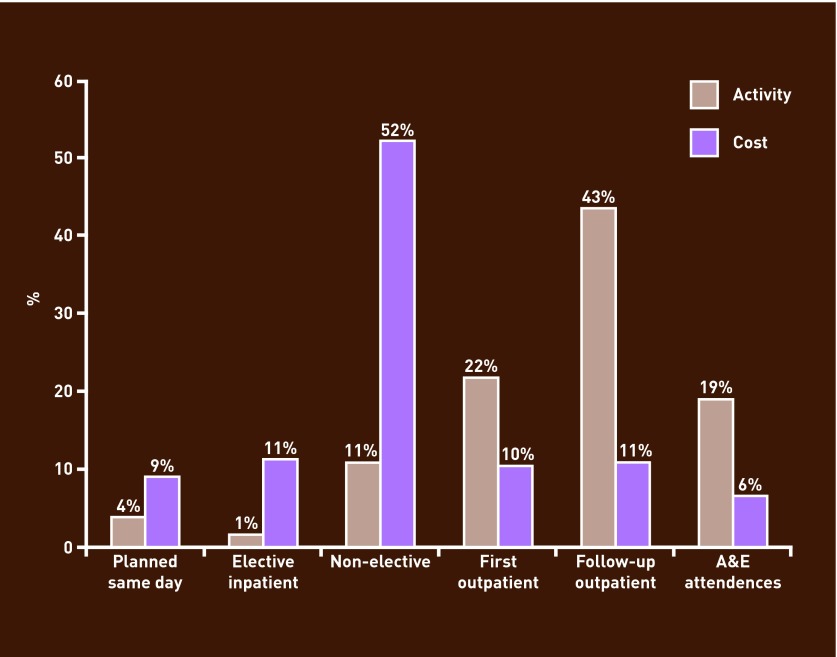

Anecdotally, when secondary healthcare activity and costs for Lincolnshire and Nottingham City were examined, it was observed that more than half of secondary care activity was for outpatient activity accounting for one-fifth of total costs, while around 10% of activity was non-elective (that is, emergency) activity but accounted for half of the costs. (Figure 1). This suggests that efforts to reduce outpatient activity may be misguided and have limited impact on overall healthcare costs. Targeting non-elective activity to prevent avoidable emergency admissions may be more productive.

Figure 1.

Secondary care activity and costs by activity type, NHS Nottingham City, 2011/2012.

Health promotion and disease prevention

Referral pathway redesign however is not the only solution. There is often insufficient effort made to reduce the need for health care in the first place. Preventable diseases account for up to 70% of the burden of illness and its associated costs. Health promotion and disease-prevention activities such as smoking cessation, diet, physical activity interventions, and screening, have good evidence for their effectiveness.7 Unfortunately, the benefits of these activities are only realised over the longer term, which does not fit with short-term commissioning perspectives.

Self-management support

Empowering self management through goal setting, shared decision making, and personalised self-care support, enables patients to make rational decisions about their own health.8 There is some evidence purporting the benefits of enabling patients with chronic diseases such as asthma, diabetes, heart failure, and COPD, to manage their own health and illness.9 Examples include the UK Expert Patient Programme, Torbay Depression Self Management Programme, and the Year of Care approach to care planning. Pilots of the latter observed reductions in hospital admissions and emergency department attendances (50% and 68% respectively). Other studies report that ‘consumer education’ reduces service use by 7–17%. However, the benefits of self management may not be realised if patients are left unsupported and prevailing paternalistic patterns of care may reinforce a state of ‘learned helplessness’ that undermine such re-ablement strategies.

Decision support: right care

Patients receiving optimised care and achieving optimal outcomes are less likely to need non-elective hospitalisation. Increasing emergency hospital admissions of patients with chronic conditions therefore indicates a failing chronic disease management system. However, recent commissioning debates have focused more on the ‘place’ of care delivery rather than the ‘appropriateness’ of care. Wide variations in clinical practice between individual clinicians, practices, and organisations also exist nationally. Improving the standardisation of high-quality care is essential, and decision support tools to assist clinicians may have an important role in this.10

Comprehensive chronic disease care

Comprehensive care for patients with chronic diseases is essential to managing health need. This encompasses the entire patient journey, from disease detection, diagnosis, routine monitoring over the years, as well as crisis care for exacerbations. Continuity of care and the integration of services are integral to this. While there is evidence of both efficacy and cost effectiveness for comprehensive care models, one evidence review also warns that ‘cost savings resulting from improved disease control take time to materialise’.11 Indeed, clinical practice is more focused on the acute processes of treatment and short-term aspects of a particular illness rather than ‘proactive, planned, patient-oriented longitudinal care’ required for chronic care.12 There is also a tendency to seek elegant ‘magic bullet’ solutions, that is, single component interventions, to deal with complex issues where multicomponent approaches are more appropriate.13

So what does and does not work?

A systematic review reported the following to be ineffective14: passive dissemination of local referral guidelines, clinicians discussing referral decisions with independent medical advisors, provision of feedback of referral rates, and access to private specialists. What was effective was active dissemination of guidelines, involvement of secondary care consultants in educational activities for primary care clinicians, use of structured referral forms, clinicians obtaining second ‘in-house’ opinion prior to referral, as well as peer review and audit. Implementing a fee-for-service system or a capitation-based system with risk-sharing with secondary and primary care were also reported to work. Measures where there was insufficient evidence of benefit included use of intermediate primary care-based services, GP fundholding schemes, shared decision-making, self-care management programmes, the use of ‘long-term conditions’ clinics in primary care, or the integration of care.15

CONCLUSION

There is a need to identify evidence-based measures that commissioners can implement to reduce healthcare demand. Understanding the mechanisms by which these measures work as well as finding effective ways of implementing change on a reluctant health workforce is also crucial. The National Institute for Health Research have commissioned a study (Health Services and Delivery Research Programme 11/1022/01) to review the international evidence for demand management that is due to report back in late 2013. The findings of this study may provide commissioners with the answers to this problem.

Provenance

Freely submitted; not externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Imison C, Naylor C. Referral management — lessons for success. London: The King’s Fund; 2010. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/referral_management.html (accessed 25 Jun 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grimshaw JM, Winkens RAG, Shirran L, et al. Interventions to improve outpatient referrals from primary care to secondary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD005471. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepperd S, Doll H, Angus RM, et al. Hospital at home admission avoidance. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD007491. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis G, Bardsley M, Vaithianathan R, et al. Do ‘virtual wards’ reduce rates of unplanned hospital admissions, and at what cost? A research protocol using propensity matched controls. Int J Integr Care. 2011;11:e079. doi: 10.5334/ijic.654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pencheon D. Managing demand: Matching demand and supply fairly and efficiently. BMJ. 1998;316(7145):1665–1667. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7145.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ensor T, Cooper S. Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19(2):69–79. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaziano TA, Galea G, Srinath Reddy K. Scaling up interventions for chronic disease prevention; the evidence. Lancet. 2007;370(9603):1939–1946. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61697-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vickery DM, Lynch WD. Demand management: enabling patients to use medical care appropriately. J Occup Environ Med. 1995;37(5):551–557. doi: 10.1097/00043764-199505000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Stewart AL, et al. Evidence suggesting that a chronic disease self-management program can improve health status while reducing hospitalization: a randomized trial. Med Care. 1999;37(1):5–14. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199901000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bright TJ, Wong A, Dhurjati R, et al. Effect of clinical decision-support systems: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(1):29–43. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-157-1-201207030-00450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coleman K, Austin BT, Brach C, Wagner EH. Evidence on the chronic care model in the new millenium. Health Affairs. 28(1):75–85. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.75. 200; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glasgow RE, Orleans CT, Wagner EH, et al. Does the chronic care model serve also as a template for improving prevention? Millbank Q. 2001;79(4):579–612. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grint K. The new public leadership challenge. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan; 2010. Wicked problems and clumsy solutions: the role of leadership; pp. 169–186. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akbari A, Mayhew A, Al-Alawi MA, et al. Interventions to improve outpatient referrals from primary care to secondary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD005471. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005471.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.RAND Europe, Ernst & Young LLP . National evaluation of the Department of Health’s Integrated Care Pilots. London: Department of Health; 2012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]