Abstract

The pathogenesis of vitiligo is still controversial. The purpose of this study was to gain insight into the nature of lymphoid cells infiltrating depigmented areas of skin in vitiligo. Immunochemical procedures were carried out in biopsies from 20 patients with active lesions to search for cells expressing CD1a, CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD8, CD20, CD25, CD30, CD56, CD68 and CD79a. Results indicate that early lesions are infiltrated mainly by dendritic cells, whereas older lesions display significantly lower proportions of these cells and increased percentages of mature T cells. This finding might suggest that the autoimmune reactivity towards melanocyte antigens might be T cell-dependent and antigen-driven. It is possible that a non-immune offence of melanocytes is responsible for the exposure of intracellular antigens, while autoreactivity might be a secondary, self-perpetuating mechanism.

Keywords: immunopathogenesis, immunopathology, lymphoid infiltrates, vitiligo

Introduction

The aetiology and physiopathology of vitiligo has been discussed widely for several years; however, several findings and clinical observations suggest strongly that vitiligo is an autoimmune-mediated disease, where melanocyte-specific reactants seem to play a pathogenetic role 1–9. Serum antibodies to melanocyte-associated antigens are found in the vast majority of patients, while their presence in healthy subjects or patients with other skin disorders is somewhat uncommon 10–14; some patients suffering vitiligo have other autoimmune conditions 7–9, mainly endocrine autoimmune diseases, and last, but not least, the use of topical or systemic immunosuppressive therapy results in clinical improvement of the disease 15–17. The autoimmune aetiology of vitiligo neither excludes nor is excluded by other aetiopathogenic mechanisms, such as psychological or neurological factors, as it is accepted increasingly that neuroimmunoendocrine networks might play a key role in many physiological and pathological situations 18.

The pathogenetic role of serum antibodies to melanocytes is supported not only by their presence in almost all vitiligo patients, but also in the recent demonstration by ourselves [10] that the titres of such antibodies are found to correlate with the clinical activity of the disease. In fact, the increase in relative amounts of melanocyte-specific serum antibodies, detected by an enzyme immunoassay, predicts clinical progression of the disease, while the decrease or stability of such amounts is associated with quiescence of the morbid process. Moreover, in-vitro experiments have demonstrated clearly that melanocyte antibodies are capable of triggering apoptosis of cultured melanocytes, and immunochemical studies show that residual melanocytes in skin biopsies from active lesions display molecular markers of apoptosis 1.

Antibody-mediated immune damage involves manifold mechanisms; in the case where autoantibodies are directed to intracellular antigens – as in the case of vitiligo – it has been demonstrated that certain antibodies of the immunoglobulin (Ig)G isotype are capable of penetrating into cells and reach their respective antigens in living cells 1,19–26. One of the many consequences of this phenomenon is the occurrence of apoptosis, triggered apparently by both the programmed and the neglect pathways 20–25. Altogether, these findings are consonant with the hypothesis that IgG antibodies directed to intracellular melanocyte-related antigens, are capable of penetrating into melanocytes and trigger their cell death by apoptosis, thus resulting in the loss of these cells without an acute inflammatory response. Typically, affected skin displays clusters of lymphocytes in juxtaposition to depigmented areas and, hence, such cells might be involved in the immunological reactions which lead eventually to the antibody-mediated apoptosis of melanocytes. We therefore decided to undertake experimental work to characterize the nature of infiltrating lymphoid cells in order to gain insight into the mechanism of autoreactivity in vitiligo.

Material and methods

Patients

Ten patients with active disseminated vitiligo who had been diagnosed within 3 months prior to their inclusion in the study (early disease) and 10 other patients who had been diagnosed more than 2 years previously (late disease) were enrolled into the study. None had ever received topical or systemic immunosuppressant therapy, and ‘early disease’ cases had had no therapy. All patients were aware of the risks and signed a Clinical Investigation Agreement to participate in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Centro de Hematología y Medicina Interna de Puebla, Laboratorios Cínicos de Puebla, and Laboratorios Clínicos de Puebla de Bioequivalencia.

Immunohistochemical studies

Punch skin biopsies were obtained from all patients. All biopsies were fixed in 10% buffered formaldehyde and paraffin-embedded by routine methods. Sections were then rehydrated by sequential immersion in xylene and decreasing water solutions of ethanol for immunochemical staining. Antibodies to CD1a, CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD8, CD20, CD25, CD30, CD56, CD68 and CD79a were used to characterize the lymphoid infiltrates in all biopsies. Citrate pH6 buffer (Citrates®; Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA, USA) was used for antigenic recovery of CD3, an ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) pH8 buffer (Trilogy®; Cell Marque) for the recovery of CD1a, CD2, CD4, CD5, CD8, CD20, CD30 and CD56 and an EDTA pH6 buffer (Decleare®; Cell Marque) for CD25, CD68 and CD79a. Immunochemical staining was performed with the aid of an automated platform (Dakoautostainer plus®; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark), and an alkaline phosphatase polymer (UltraVision Labeled Polimer®; Labvision) and Fast Red C were used to unravel the binding of the different antibodies 1,27–29. Different positive and negative control tissue samples were run simultaneously to ascertain the sensitivity and specificity of each antigen–antibody reaction in the system.

Two independent and skilled professionals counted the proportions of cells expressing each of the antigens in each of the biopsies. At least 200 cells were counted to determine the percentages of infiltrating cells expressing each of the CD antigens that were searched.

Statistical analysis

A statistical t-test for paired observations was used to compare the mean values of the percentages of the different cell types between early and late disease lesions infiltrates. The MedCalc® (Ostend, Belgium) software package was used for this purpose.

Results

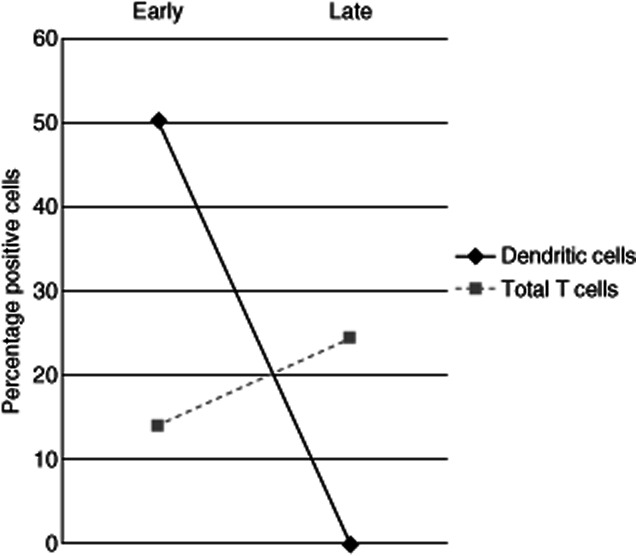

Table 1 summarizes the mean values and standard deviations of such figures in both biopsies from early and late disease biopsies. Figure 1 depicts the main changes in the proportions of cell subsets in biopsies from patients with lesions less than 3 months old (Fig. 2), and those from patients with lesions more than 2 years old.

Table 1.

Relative proportions of cell subsets in infiltrating cells in vitiligo patients with early and late disease

| Antigen | Early disease | Late disease | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean, % | s.d.† | Mean, % | s.d. | |

| CD1 | 62·3 | 26·49 | 24·3 | 17·85 |

| CD2 | 12·0 | 11·72 | 27·2 | 11·08 |

| CD3 | 14·1 | 1·19 | 21·5 | 1·08 |

| CD4 | 4·9 | 6·19 | 2·9 | 4·99 |

| CD5 | 1·1 | 1·91 | 23·1 | 20·90 |

| CD8 | 13·8 | 21·59 | 14·6 | 18·57 |

| CD20 | 5·7 | 16·02 | 0·6 | 0·84 |

| CD25 | 5·8 | 4·89 | 8·9 | 9·80 |

| CD30 | 0·2 | 0·63 | 0·2 | 0·42 |

| CD56 | 0·5 | 1·26 | 0 | 0 |

| CD68 | 12·9 | 6·65 | 23·1 | 19·86 |

| CD79a | 3·4 | 0·96 | 0·6 | 1·26 |

s.d.: Standard deviation. All values were obtained from duplicate counts in each of the 10 specimens in both groups.

Fig. 1.

Changes in the proportions of cell subsets from early to late disease biopsies. Dendritic cells are defined as CD1a+, CD2–, CD3– cells; total T cells are CD2+, CD3+ cells.

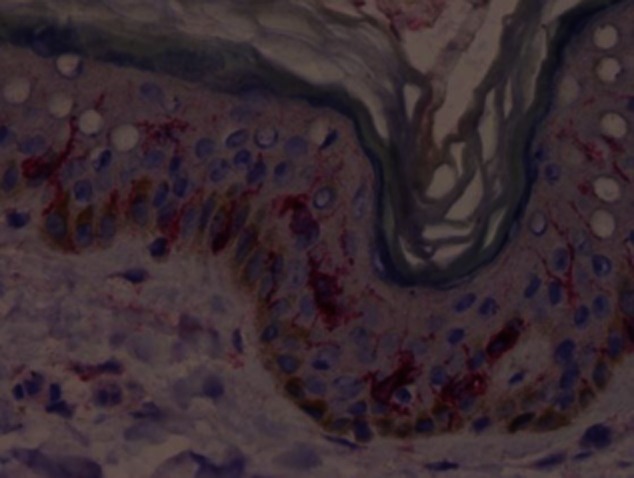

Fig. 2.

Immunostaining of an early vitiligo skin lesion with an anti-CD1a monoclonal antibody.

The most striking and constant finding was the dramatic decrease of dendritic (CD1a+CD2–CD3–) cells from early to late lesions, encompassed by an increase in the proportions of total T cells. These are the only statistically significant (PStudent's t < 0·05) differences between the two groups of patients. The proportions of helper and cytotoxic T cells; B cells, activated cells and natural killer (NK) cells were not significantly different. In previous studies we have demonstrated that peripheral blood lymphocyte subsets are not different in patients with vitiligo than in normal individuals, despite the time of evolution of the disease; therefore, it seems that these changes are localized to the skin lesions and do not result from a central disorder. Also unexpected was the scant number of B cells in early stages of the disease and its practical absence in late stages of the disorder.

Discussion

The core finding of this study is suggestive of the possibility that the immune self-reactivity seen in vitililgo is antigen-driven, rather than spontaneous. For a long time it has been considered that triggering of autoimmune reactants, mainly autoantibodies, does not follow the regular pathway as non-self-antigens. Anti-DNA antibodies, for instance, are not known to be produced after DNA fragments are presented to T cells by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules in antigen-presenting cells in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, nor are rheumatoid factors believed to be produced after IgG molecules or immune complexes are presented to the immune system. For the vast majority of autoantibodies it is believed that autoreactive clones are ‘freed’ from regulatory mechanisms, thus resulting in the spontaneous activation of such clones and the synthesis and secretion of their autoantibody products 30. Polyclonal activation, superantigens, equivocal co-operation and other mechanisms have been mentioned and proposed; however, it is thought generally that specific antigen-driven responses are not involved in autoimmune diseases 30.

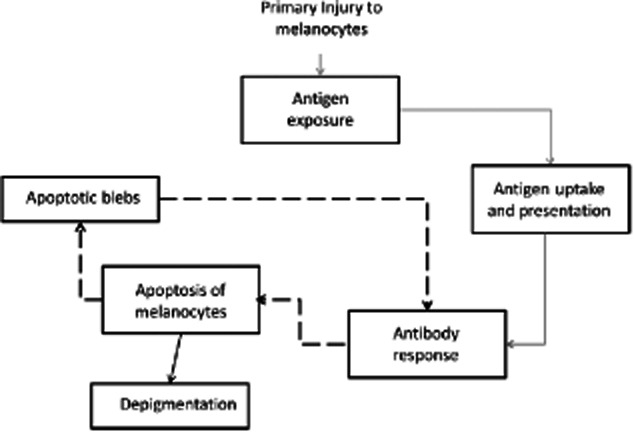

The finding of abundant dendritic cells in infiltrates from early biopsies suggests strongly that an antigen-presentation process is taking place at this stage of the pathogenetic process. It is possible, therefore, to hypothesize that a primary non-autoimmune phenomenon causes the breakdown of melanocytes. This primary process, which could be traumatic, physical or infectious, might result in the exposure and uptake of intracellular melanocyte-associated antigens by professional antigen-presenting cells and – in individuals with genetic susceptibility – trigger a ‘traditional’ T cell-dependent immune response towards previously hidden self-antigenic structures. The antibody response to such self-antigens might aggravate the condition by inducing apoptosis of melanocytes, and the resulting apoptotic blebs might, in turn, stimulate further self-antigen-reactive cells 31,32. This process might close a vicious circle and self-perpetuate the progression of the disease. The proposed mechanism is summarized in Fig. 3, and is consonant with the clinical course of this condition. According to this scheme, dendritic cells, which have been also found in vitiligo lesions by others 33, might play a role in the initial stages of the disease as antigen-presenting cells; however, once the antibody response is developed, apoptotic bodies might induce antibody responses acting as antigen-presenting structures without the participation of dendritic cells. In later stages of the disease, T cells might be stimulated directly by apoptotic bodies released by antibody penetration 20–24, and this might explain their prevalence in infiltrates of late vitiligo lesions. Finally, it is reasonable to propose that antibody synthesis and secretion does not take place in local lymphoid infiltrates, as B cells or antibody-producing cells are practically absent among these cells. The most plausible explanation is that B cell activation takes place in regional lymphoid tissue.

Fig. 3.

A non-immunological mechanism causes primary damage to melanocytes, resulting in self-antigen exposure and uptake by dendritic cells. The antibody response induces apoptosis of melanocytes and the resulting apoptotic bodies perpetuate the autoimmune reactivity, without further participation of professional antigen-presenting cells.

The breakdown of self-tolerance in the initial phases of this disease might result from escape from regulatory mechanisms, particularly the extrinsic form of dominant tolerance that has been imputed to CD4+ regulatory T cells 34, also known as natural regulatory T cells (nTreg). Results from several in-vitro studies have revealed that nTreg can exert suppressive effects against multiple cell types involved in immunity and inflammation 35. These include the induction, effector and memory function of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, antibody production and isotype-switching of B cells, inhibition of NK and T cell cytotoxicity, maturation of dendritic cells and function and survival of neutrophils. The inhibitory effects are all influenced in some way by the forkhead box protein 3 (FoxP3) transcription factor 36. In recent years, attention has been focused upon the regulatory role of interleukin (IL)-10-producing B cells on T cells to limit autoimmune reactivity and, although several questions remain unanswered, evidence of their potential role on self-tolerance is increasing 37. Screening for the presence of C38+ IL-10+ B cells, as well as CD4+FoxP3+ and CD8+FoxP3+ T cells in infiltrates of very early vitiligo lesions, might unravel useful information as to their role in the triggering of the pathogenic process.

Our findings might shed useful information for the development of new strategic approaches in the treatment of this condition. On one hand, it is advisable to use immunosuppressant drugs to inhibit the immune reactivity towards melanocytes while, on the other hand, the use of corticosteroids should be banned from the therapeutic repertoire of this disease as they are known to induce apoptosis of different cells at therapeutic doses. In severe cases of active disease, a promising approach is the administration of humanized chimeric monoclonal antibodies to deplete antibody-secreting cells and hence break the vicious circle that perpetuates the progression of vitiligo. In a pilot study, we administered intravenous boluses of a monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody (Rituximab) to five patients with active progressive disease, and the results (to be published elsewhere) were very encouraging.

Vitiligo, in its primary form, is not a life-threatening disease; however, the cosmetic and, most importantly, the psychological effects of the condition might be overwhelming 38,39. Evidence-based therapeutic approaches have rarely been used in this disease, and we trust that our efforts will contribute towards this goal.

Disclosure

No personal, institutional or corporate financial conflicts are involved in the production and publication of this information.

References

- 1.Ruiz-Argüelles A, Jimenez-Brito G, Reyes-Izquierdo P, Pérez-Romano B, Sánchez-Sosa S. Apoptosis of melanocytes in vitiligo results from antibody penetration. J Autoimmun. 2007;29:281–286. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van den Wijngaard R, Wankowicz-Kalinska A, Pals S, Weening J, Das P. Autoimmune melanocyte destruction in vitiligo. Lab Invest. 2001;81:1061–1067. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kovacs SO. Vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;38:647–666. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uchi H, Stan R, Turk MJ, et al. Unraveling the complex relationship between cancer immunity and autoimmunity: lessons from melanoma and vitiligo. Adv Immunol. 2006;90:215–241. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(06)90006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kemp EH, Waterman EA, Weetman AP. Immunological pathomechanisms in vitiligo. Exp Rev Mol Med. 2001;3:1–22. doi: 10.1017/S1462399401003362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halder RM, Grimes PE, Cowan CA, Enterline JA, Chakrabarti SG, Kenney JA. Childhood vitiligo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:948–954. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70119-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park S, Albert DM, Bolognia JL. Ocular manifestations of pigmentary disorders. Dermatol Clin. 1992;10:609–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ochi Y, DeGroot LJ. Vitiligo in Graves' disease. Ann Intern Med. 1969;71:935–940. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-71-5-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gould IM, Gray RS, Urbaniak SJ, Elton RA, Duncan LJ. Vitiligo in diabetes mellitus. Br J Dermatol. 1985;113:153–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiménez-Brito G, Garza-de-La-Peña E, Pérez-Romano B, Ruiz-Argüelles A. Serum antibodies to melanocytes in patients with vitiligo are predictors of disease progression. Skin Med J. 2012;10 in press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cato AC, Wade E. Molecular mechanisms of anti-inflammatory action of glucocorticoids. Bioessays. 1996;18:371–378. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill LL, Shreedhar VK, Kripke ML, Owen Schaub LB. A critical role for Fas ligand in the active suppression of systemic immune responses by ultraviolet radiation. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1285–1294. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.8.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song YH, Connor E, Li Y, Zorovich B, Balducci P, Maclaren N. The role of tyrosine in autoimmune vitiligo. Lancet. 1994;344:1049–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91709-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gulhar A, Zelickson B, Ulman Y, Etzioni A. In vivo destruction of melanocytes by the IgG fraction of serum from patients with vitiligo. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:683–686. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12324456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alghamdi KM, Khurrum H, Taieb H, Ezzedibe K. Treatment of generalized vitiligo with anti TNF-α agents. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:534–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pagliarello C, Paradisi A. Topical tacrolimus is useful for avoiding suction-blister epidermal grafting depigmentation in non segment vitiligo: a case report. Acta Derm Venereol. 2012;92:181–182. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nisticó S, Chiricozzi A, Saraceno R, Schipiani C, Chimenti S. Vitiligo treatment with monochromatic excimer light and tacrolimus: results of an open randomized controlled trial. Photomed Laser Surg. 2012;30:26–30. doi: 10.1089/pho.2011.3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zmijewski AJ, Slominski AT. Neuroendocrinology of the skin: an overview and selective analysis. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:3–10. doi: 10.4161/derm.3.1.14617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alarcón-Segovia D, Ruíz-Argüelles A, Llorente L. Broken dogma: penetration of autoantibodies into living cells. Immunol Today. 1996;17:163–164. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(96)90258-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruiz-Argüelles A, Rivadeneyra-Espinoza L, Alarcón-Segovia D. Antibody penetration into living cells: pathogenic, preventive and immunotherapeutic implications. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:1881–1887. doi: 10.2174/1381612033454379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruiz-Argüelles A, Pérez-Romano B, Llorente L, Alarcón-Segovia D, Castellanos JM. Penetration of anti-DNA antibodies into immature live cells. J Autoimmun. 1998;11:547–556. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1998.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portales-Pérez D, Alarcón-Segovia D, Llorente L, et al. Penetrating antiI-DNA monoclonal antibodies induce activation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Autoimmun. 1998;11:563–571. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1998.0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rivadeneyra-Espinoza L, Ruiz-Argüelles A. Cell-penetrating anti-native DNA antibodies trigger apoptosis through both the neglect and programmed pathways. J Autoimmun. 2006;26:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shcmidt-Acevedo S, Perez-Romano B, Ruiz-Argüelles A. LE cells result from phagocytosis of apoptotic bodies induced by antinuclear antibodies. J Autoimmun. 2000;15:15–20. doi: 10.1006/jaut.2000.0381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alarcón-Segovia D, Llorente L, Ruiz-Argüelles A. The penetration of autoantibodies into cells may induce tolerance to self by apoptosis of autoreactive lymphocytes and cause autoimmune disease by dysregulation and/or cell damage. J Autoimmun. 1996;9:295–300. doi: 10.1006/jaut.1996.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alarcon-Segovia D, Ruiz-Arguelles A, Llorente L. Antibody penetration into living cells III. Effect of anti-ribonucleoprotein IgG on the cell cycle of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1982;23:22–26. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(82)90067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joyner A, Wall N. Immunohistochemistry of whole-mount mouse embryos. CSH Protoc. 2008;2008:pdb.prot4820. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burnett R, Guichard Y, Barale E. Immunohistochemistry for light microscopy in safety evaluation of therapeutic agents: an overview. Toxicology. 1997;119:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(96)03600-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramos-Vara JA. Technical aspects of immunohistochemistry. Vet Pathol. 2005;42:405–426. doi: 10.1354/vp.42-4-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shoenfeld Y, Cervera R, Gershwin ME, editors. Diagnostic criteria in autoimmune disease. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perl A. Pathogenesis and spectrum of autoimmunity. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;900:1–9. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-720-4_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hossain A, Radwan FF, Doonan BP, et al. A possible cross-talk between autophagy and apoptosis in generating an immune response in melanoma. Apoptosis. 2012;17:1066–1078. doi: 10.1007/s10495-012-0745-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang CQ, Cruz-Iñigo AE, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Th17 cells and activated dendritic cells are increased in vitiligo lesions. PLoS ONE. 2011;25:e18907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwartz RH. Natural regulatory T cells and self tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:327–330. doi: 10.1038/ni1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyara M, Sakaguchi S. Natural regulatory T cells: mechanisms of suppression. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rouse BT. Regulatory T cells in health and disease. J Intern Med. 2007;262:78–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gray D, Gray M. What are regulatory B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:2677–2679. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Porter J, Beuf AH, Lerner AB, Nordlund JJ. Response to cosmetic disfigurement: patients with vitiligo. Cutis. 1987;39:493–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Porter J, Beuf AH, Nordlund JJ, Lerner AB. Psychological reaction to chronic skin disorders: a study of patients with vitiligo. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1979;1:73–77. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(79)90081-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]