Abstract

Cohen syndrome (CS) is a rare autosomal recessive condition caused by mutations and/or large rearrangements in the VPS13B gene. CS clinical features, including developmental delay, the typical facial gestalt, chorioretinal dystrophy (CRD) and neutropenia, are well described. CS diagnosis is generally raised after school age, when visual disturbances lead to CRD diagnosis and to VPS13B gene testing. This relatively late diagnosis precludes accurate genetic counselling. The aim of this study was to analyse the evolution of CS facial features in the early period of life, particularly before school age (6 years), to find clues for an earlier diagnosis. Photographs of 17 patients with molecularly confirmed CS were analysed, from birth to preschool age. By comparing their facial phenotype when growing, we show that there are no special facial characteristics before 1 year. However, between 2 and 6 years, CS children already share common facial features such as a short neck, a square face with micrognathia and full cheeks, a hypotonic facial appearance, epicanthic folds, long ears with an everted upper part of the auricle and/or a prominent lobe, a relatively short philtrum, a small and open mouth with downturned corners, a thick lower lip and abnormal eye shapes. These early transient facial features evolve to typical CS facial features with aging. These observations emphasize the importance of ophthalmological tests and neutrophil count in children in preschool age presenting with developmental delay, hypotonia and the facial features we described here, for an earlier CS diagnosis.

Keywords: Cohen syndrome, facial phenotype, changing phenotype, VPS13B gene

Introduction

Cohen syndrome (CS) (OMIM 216550) is a rare autosomal recessive condition caused by mutations and/or copy number variations in the VPS13B gene located on chromosome 8q22-q23 (OMIM 607817).1, 2, 3, 4, 5 It is characterized by a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations6, 7, 8, 9 including mental retardation, characteristic facial gestalt, progressive chorioretinal dystrophy (CRD), intermittent neutropenia, the hallmarks for clinical diagnosis,8 in addition to childhood hypotonia, postnatal microcephaly, truncal obesity, slender extremities, joint hyperextensibility and myopia. The typical facial gestalt of CS comprises thick hair and a low hairline, downward-slanting and wave-shaped palpebral fissures, thick eyebrows and eyelashes, a prominent, beak-shaped nose with a high nasal bridge, malar hypoplasia and a high-arched palate. The philtrum is usually short and upturned and associated with maxillary prognathia, leading to an open mouth expression due to labial incompetence10, 11 and the appearance of prominent central incisors. When asked to smile, patients with CS grimace, screwing up their nose and eyes and further shortening their philtrum.1, 7, 8 To date, the late appearance of certain clinical signs have been the main cause of delay in the diagnosis.12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Indeed, in preschool age (3– to <6 years) and even more in infants <3 years of age, the facial characteristics are less noticeable:3, 8, 17 for example, CRD is either not yet apparent on fundus examination or rarely investigated by electroretinography except when severe clinical visual disturbances are present, and neutropenia can be present but is rarely screened for, or even considered, in the absence of clinical manifestations. The goal of this study was to describe the facial features in the beginning of life, including the preschool period, and to analyse their evolution with advancing age to find clues for an earlier diagnosis, in a series of 17 patients with molecularly confirmed CS. Finding early clinical clues would indeed be useful to search for mutations or large rearrangements in the VPS13B gene for early diagnosis and genetic counselling.

Patients and methods

A total of 72 patients from 62 families with a suspicion of CS were referred to the genetic laboratory of Dijon University Hospital for VPS13B testing. At least one genetic variant (mutation and/or large intragenic rearrangement) was identified in 21 patients from 15 families using sequencing analysis and/or 244 k Agilent array-CGH or 8 × 15 k targeted array-CGH.5, 18 All these patients were diagnosed with CS according to both Chandler's and Kolehmainen's criteria.8, 9 Parents were asked by their referring physician to send photographs of their children from early infancy to the last examination. We received photographs and written consent for the publication of photographs of 17 patients from 13 families (mean age±SD at diagnosis: 19.6±10.8 years, 5 females and 12 males). The clinical and molecular characteristics of the children other than facial dysmorphism are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical and molecular characteristics of the patients.

| Patient | Age (years) | Nucleotide change and/or CNVs | Intron/exon | Facial dysmorphism (typical/atypical) | Hallmarks of CS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1-F1 | 11 | c.436C>T/DelEX36-37 | EX 5, EX 36-37 | Typical | CRD |

| P2-F2 | 43 | c.10139_10143dupCGCCA/DupEX9-12 | EX 56, EX 9-12 | Typical | CRD, neutropenia |

| P2-F3 | 46 | c.10139_10143dupCGCCA/DupEX9-12 | EX 56, EX 9-12 | Typical | CRD, neutropenia |

| P7-F6 | 20 | c.1220delA/ c.7286delT | EX 9, EX 40 | Typical | CRD, neutropenia |

| P10-F8 | 22 | c.2074C>T/c.5426_5427dupAG | EX 15, EX 34 | Typical | CRD, neutropenia |

| P11-F8 | 18 | c.2074C>T/c.5426_5427dupAG | EX 15, EX 34 | Typical | CRD, neutropenia |

| P15-F11 | 10 | c.3427C>T/c.10880C>T+c.10883_10900delCGAGGCAGCTTGTGCACG | EX 23, EX 56 | Typical | CRD |

| P18-F14 | 14 | c.916_917delGA/c.1006C>T | EX 7, EX 8 | Typical | CRD, neutropenia |

| P19-F14 | 8 | c.916_917delGA/c.1006C>T | EX 7, EX 8 | Typical | CRD, neutropenia |

| P22-F17 | 15 | IVS47(-2)A>G/DelEX36 | IVS 47, EX 36 | Typical | CRD, neutropenia |

| P23-F17 | 21 | IVS47(-2)A>G/DelEX36 | IVS 47, EX 36 | Typical | CRD |

| P24-F18 | 25 | DupEX 31-33/DupEX 31-33 | EX 31–33 | Atypical | CRD, neutropenia |

| P25-F18 | 17 | DupEX 31-33/DupEX 31-33 | EX 31–33 | Atypical | CRD |

| P40-F33 | 13 | c.1733delT/c.11695_11698delAGTG | EX 13, EX 61 | Typical | CRD |

| P51-F43 | 14 | IVS30+2 T>C/IVS51 -1 G>T | IVS 30, IVS 51 | Typical | CRD, neutropenia |

| P68-F58 | 10 | Del IVS43-44/c.7643_7644delTCinsAA | IVS 43–44, EX 42 | Typical | CRD, neutropenia |

| P72-F62 | 26 | c.8515C>T/c.8515C>T | EX 46 | Typical | CRD, neutropenia |

Abbreviations: CNV, copy number variations; CRD, chorioretinal dystrophy; CS, Cohen syndrome.

Photographs of the patients at different ages were examined by the same physicians and clinical features were classified according to the period of life at which they were first noticed. The classification was as follows: infancy (0 to <3 years), preschool age (3 to <6 years), school age (6 to <14 years), adolescence (14 to <20 years) and adulthood (≥20 years).

Results

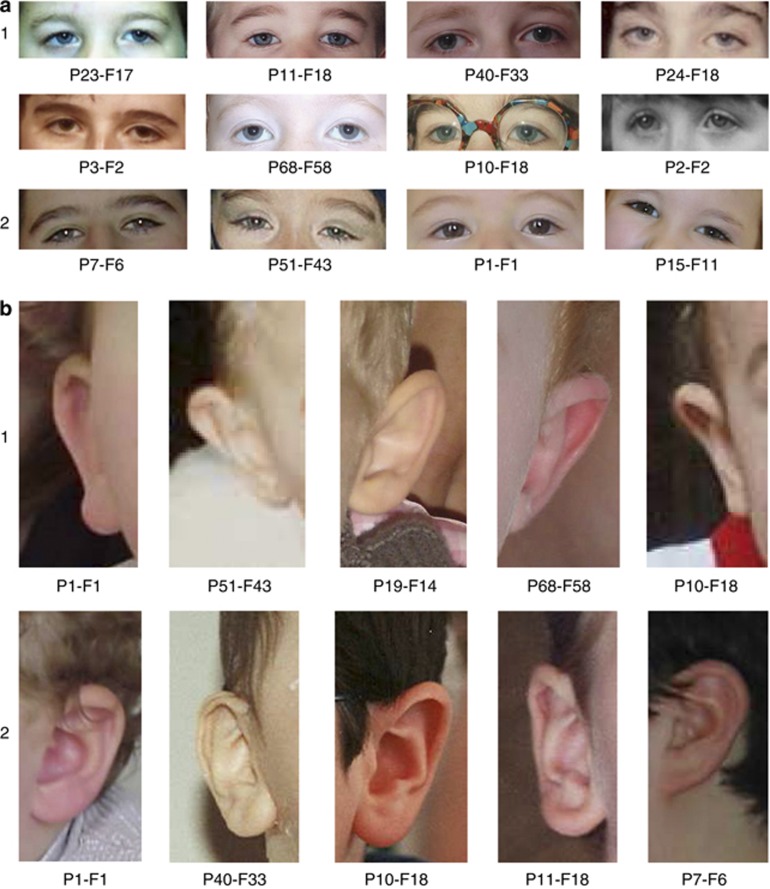

First, on analysing the facial phenotype of our patients before 3 years of age, we noted that the common CS facial features were not apparent in this age range. Conversely, they already shared common facial features, described below, that are usually not reported in older CS patients at the time of diagnosis. The majority of these clinical signs were not noticeable during the first year of life (Figure 1). However, in the 17 patients for whom photographs were available during late infancy and early preschool age, homogenous characteristics can be noticed, including (Table 2): a short neck (15/17 patients), a square face with micrognathia and full cheeks (16/17 patients), a hypotonic facial appearance (15/17 patients), epicanthic folds (15/17 patients), a strabismus (8/17 patients) (Figure 1 and Figures 2a1 and 2), long ears with an everted upper part of the auricle and/or a prominent lobe (16/17 patients) (Figure 1 and Figures 2b1 and 2), a relatively short philtrum (14/17 patients), a small and open mouth with downturned corners, thick lower lip and a marked mentolabial sulcus (13/17 patients) (Figures 1 and 2c1), and a normal-sized milk teeth in the normal position (17/17 patients).

Figure 1.

Facial phenotype in infancy and preschool age (<3 years); Clinical features of patients P1-F1 (19 months), P2-F2 (1 year), P3-F2 (1 year), P10-F8 (6 months), P11-F8 (15 months), P22-F17 (2 years), P23-F17 (2 years), P40-F33 (7 months), P51-F43 (9 months), P68-F58 (1 year).

Table 2. Evolving facial features present in late infancy/preschool age and in late childhood/adolescence in CS patients.

| Late infancy/preschool | Late childhood/adolescence | |

|---|---|---|

| Head shape | Postnatal microcephaly | Microcephaly, tendency to turricephaly |

| Face shape | Square and hypotonic with micrognathia and full cheeks | Elongated |

| Neck | Short | Without significant particularity |

| Eyes | Type 1: marked epicanthic folds and downward-slanting, high-arched palpebral fissures with frequent unilateral or bilateral ptosis Type 2: elongated, wave-shaped palpebral fissures with long, thick eyelashes | Downward-slanting and wave-shaped palpebral fissures |

| Ears | Long ears with an everted upper part of the auricle and/or a prominent lobe | No special features |

| Hair | No special features | Thick hair and low hairline |

| Nose | No special features | Prominent beak-shaped nose with a high nasal bridge |

| Philtrum and mouth | Relatively short philtrum; small, open mouth with downturned corners, thick lower lip and marked mentolabial sulcus | Short philtrum upturned and associated with maxillary prognathia; open mouth expression and appearance of prominent central incisors |

| Smile | No special features | Grimacing smile |

Abbreviation: CS, Cohen syndrome.

Figure 2.

(a): Focus on the two characteristic eyes shapes in patients with CS (infancy to school age); (1) Type 1: marked epicanthic folds, downward-slanting, high-arched palpebral fissures often with unilateral or bilateral ptosis. (2) Type 2: elongated, wave-shaped palpebral fissures with long, thick eyelashes. (b) Focus on characteristic ear shapes in patients with CS (infancy to school age); (1) long ears with an everted upper part of the auricle (2) large lobes. (c) Focus on the lower part of the face in patients with CS; (1) infancy: small, open mouth with downturned corners, a relatively short philtrum, thick lower lip and micrognathia with a marked mentolabial sulcus. (2) Adolescence and adulthood: short, upturned philtrum, thick lower lip, open mouth, prominent central incisor.

In addition, two different characteristic eye shapes could clearly be described in this age range. Type 1 included marked epicanthic folds and downward-slanting, high-arched palpebral fissures with frequent unilateral or bilateral ptosis (Figures 2a1) (8/17 patients), whereas type 2 comprised elongated, wave-shaped palpebral fissures with long, thick eyelashes (Figures 2a2) (9/17 patients). All patients belong to each other group.

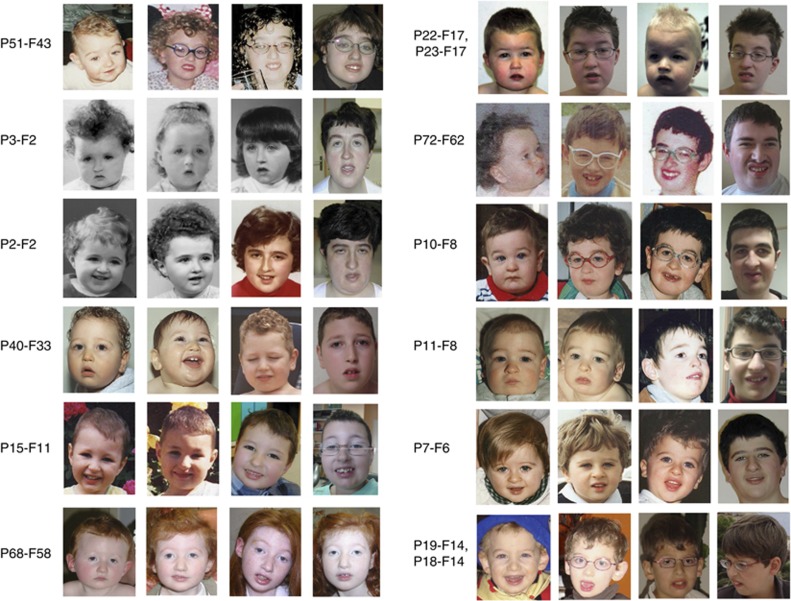

From 3 years until 6 years, the facial phenotype tended to change significantly and the typical facial features of CS became progressively more striking (Figure 3). The microcephaly became more marked with a tendency to turricephaly leading to the elongation of the face, notably with a long forehead (Figure 3). The hair became thick and dense and malar hypoplasia became noticeable. The philtrum appeared shortened and the lower lip thicker. The permanent front teeth became prominent with frequent diastema. Ptosis was often present. The downward-slanting, wave-shaped palpebral fissures were more marked and the eyelashes became long and thick (Figures 2a and 3). At this period of life, the myopia and/or chorioretinal dystrophy were easily detected.

Figure 3.

Facial phenotype from early infancy to school age or adulthood (from left to right); Clinical features of patients P51-F43, P3-F2, P2-F2, P40-F33, P15-F11, P68-F58, P22-F17, P23-17, P72-F62, P10-F8, P11-F8, P7-F6, P19-F14, P18-F14.

At adolescence, the facial characteristics became even more obvious (Figure 3 and Table 2). The face lengthened, the nose became prominent and beak-shaped with a high nasal root. The eyebrows became thicker. The philtrum was short and upturned contributing to the classical grimacing appearance when smiling (Figures 2c2 and 3).

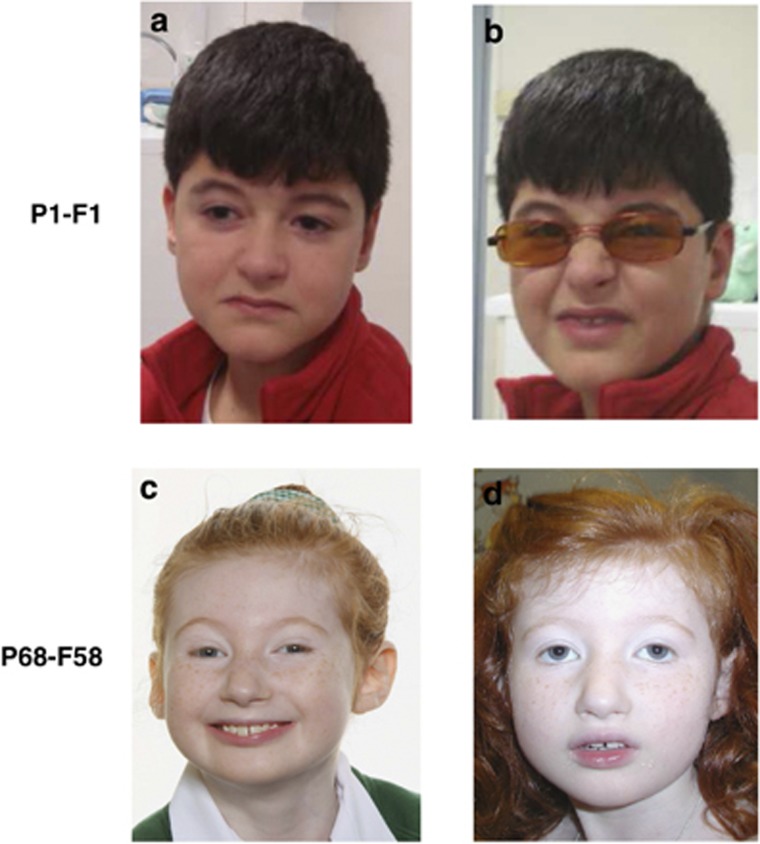

Interestingly, for some patients, the typical facial gestalt appeared only with specific facial expressions (Figure 4). For example, patient P1-F1 (10 years) did not present an open mouth expression, his philtrum was not very short, and the corners of his mouth were downturned (Figure 4a). However, when he attempted to smile, his face adopted the typical grimacing appearance of CS (Figure 4b). Conversely, patient P68-F58, aged 10 years, had a less typical facial gestalt of CS when she was smiling (Figure 4c and d).

Figure 4.

Changing facial features with facial expression; (a, b) (P1-F1): atypical facial phenotype at rest (a) and typical grimacing appearance when smiling (b). (c, d) (P68-F58): less typical facial feature when smiling.

Nevertheless, for two patients (P24-F18 and P25-F18 ), the facial phenotype remained atypical in spite of increasing age (Figure 5). Indeed, besides atypical facial features, P24-F18 displayed gynoid-type rather than android-type obesity (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Less typical facial phenotype of patients with CS (patients P24-F18 and P25-18).

Discussion

The great majority of reported patients with CS are diagnosed in the school age, that is over 6 years, in adolescence or in adulthood. There are very few reports of CS diagnosed in children before 6 years and even fewer before 3 years of age.2, 7, 8, 13, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21 At least four explanations can be suggested:

(i) Nonspecific clinical past history (born full-term after an uneventful pregnancy with normal birth and growth measurements, moderate feeding difficulties and hypotonia in the first year of life, and non-progressive developmental delay).7, 8, 13, 20

(ii) The typical facial gestalt of CS is less noticeable in the preschool age.7, 8, 12, 13, 17, 22 This was confirmed by our study. CS suspicion is again more difficult in this early age range as the other CS symptoms such as slender extremities and truncal obesity may be either not yet present or mildly expressed.

(iii) Neutropenia is rarely identified due to the absence of clinical consequences in the majority of cases.

(iv) Although ocular symptoms may be present in some cases with poor visual contact from the first months of life, CRD is not diagnosed early, often because electroretinography is rarely performed at this age.7, 8, 21 It must be underlined that when investigated under the age of 6 years, CRD and myopia can be evidenced in a significant number of patients. Among 160 CS patients with VPS13B mutations or intragenic rearrangements reported in the literature, 23 were aged under 6 years at diagnosis (age range: 1.3 to 5.8 years). CRD was investigated in all patients and was diagnosed in 12 (52%) and severe myopia in 19 out of 21 (90%) investigated patients. In all patients CRD or myopia was present.12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 22, 23

Thus, CS early diagnosis in late infancy and early preschool age (2–5 years) is a real challenge for physicians. We therefore searched for clues that could improve the detection of CS in childhood by describing the facial phenotype of 17 patients with a molecular diagnosis of CS from infancy onwards. Interestingly, we show that CS children may already share common facial features that tend to change significantly with increasing age. Table 2 compares the clinical features that we noticed in our 17 patients in the preschool period to those commonly observed later. Concerning any differential diagnosis, it must be pointed out that these preschool period clinical features are not specific and do not suggest any other well-defined dysmorphic syndrome. If neutrophil count is performed in patients with developmental delay and shows neutropenia, CS can be suspected; CRD, when evidenced, reinforces CS suspicion but it is present in only about half of the patients in this period of life.12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 22, 23

Interestingly, in our series, 2 out of 17 patients did not display typical facial features even with advancing age (P24-F18 and P25-F18) (Figure 5). In P25-F18, the grimacing expression of the face was present, but there were no photographs showing this specific expression, demonstrating that it can be very difficult to raise a diagnosis of CS on photographs alone. P24-F18 has a more generalized atypical phenotype, with gynoid-type obesity (Figure 5), which is not a classical feature of CS. There are few reports of atypical facial features in CS patients. Seifert et al16 reported a patient with two point mutations (patient 6) who lacked the characteristic facial features and presented with everted lips, a bulbous nasal tip and normal-appearing philtrum. Rivera-Brugues et al3 reported a patient with a copy number variation spanning not only exons 1–17 of the VPS13B gene, but also the neighbouring exon 4 of the ORS2 gene (patient 3). The patient had a flat face with a broad, flat nasal bridge and almond-shaped eyes, a short philtrum with a thin vermillion border, and deep-set ears with overfolded helices. These considerations, joined to the patients with partial CS facial features (P1-F1 and P68-F58) observed in our study, highly reinforce the interest of a diagnosis in the early period of life in CS.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have provided photographic evidence confirming that the diagnosis of CS can be very difficult in preschool children because of lack of the typical facial features. However, we have shown that several common facial characteristics can be seen in young children with CS and these may aid in the early suspicion of the condition. The introduction of a neutrophil count in the work-up for children in preschool age presenting with developmental delay and the use of electroretinography when poor visual contact is suspected or myopia detected should also assist in an earlier molecular diagnosis of CS and thus optimize genetic counselling.

Methods

It is a descriptive study. We studied and compared facial phenotype of CS patients at different ages and with data from the literature.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to the patients and their parents for their participation in this study. We thank Philip Bastable from the ‘Pôle Recherche' of Dijon University Hospital for helpful review of this article. We thank the Regional Council of Burgundy for their financial support of the project.

Authors contributions

Recruitment and Phenotyping was done by Salima El Chehadeh-Djebbar, Edward Blair, Muriel Holder-Espinasse, Anne Moncla, Anne-Marie Frances, Marlène Rio, François-Guillaume Debray, Patrick Rump, Alice Masurel-Paulet, Frédéric Huet, Christel Thauvin-Robinet, Laurence Faivre. Experimental analysis: Nadège Gigot, Patrick Callier, Laurence Duplomb, Bernard Aral.

Authors informations

Our lab is the reference centre for Cohen syndrome molecular diagnosis in France as we are alone in testing VPS13B gene, giving us some know-how in this field and leading to several publications and research projects.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kolehmainen J, Black GCM, Saarinen A, et al. Cohen syndrome is caused by mutations in a novel gene, COH1, encoding a transmembrane protein with a presumed role in vesicle-mediated sorting and intracellular protein transport. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1359–1369. doi: 10.1086/375454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balikova I, Lehesjoki AE, de Ravel TJ, et al. Deletions in the VPS13B (COH1) Gene as a Cause of Cohen Syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:E845–E854. doi: 10.1002/humu.21065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Brugués N, Albrecht B, Wieczorek D, et al. Cohen syndrome diagnosis using whole genome arrays. J Med Genet. 2011;48:136–140. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2010.082206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parri V, Katzaki E, Uliana V, et al. High frequency of COH1 intragenic deletions and duplications detected by MLPA in patients with Cohen syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2010;18:1133–1140. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Chehadeh-Djebbar S, Faivre L, Moncla A, et al. The power of high-resolution non-targeted array-CGH in identifying intragenic rearrangements responsible for Cohen syndrome. J Med Genet. 2011;48:e1. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2011.088948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MM, Hall BD, Smith DW, et al. A new syndrome with hypotonia, obesity, mental deficiency, and facial, oral, ocular and limb anomalies. J Pediatr. 1973;83:280–284. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(73)80493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivitie-Kallio S, Norio R. Cohen syndrome: essential features, natural history, and heterogeneity. Am J Med Genet. 2001;102:125–135. doi: 10.1002/1096-8628(20010801)102:2<125::aid-ajmg1439>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler KE, Kidd A, Al-Gazali L, et al. Diagnostic criteria, clinical characteristics, and natural history of Cohen syndrome. J Med Genet. 2003;40:233–241. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.4.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolehmainen J, Wilkinson R, Lehesjoki AE, et al. Delineation of Cohen syndrome following a large-scale genotype-phenotype screen. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:122–127. doi: 10.1086/422197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurmerinta K, Pirinen S, Kovero O, Kivitie-Kallio S. Craniofacial features in Cohen syndrome: an anthropometric and cephalometric analysis of 14 patients. Clin Genet. 2002;62:157–164. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.620209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Ballesta C, Pérez-Lajarín L, Lillo OC, Bravo-González LA. New oral findings in cohen syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:681–687. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk MJ, Feiler HS, Neilson DE, et al. Cohen syndrome in the Ohio Amish. Am J Med Genet Part A. 2004;128A:23–28. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennies HC, Rauch A, Seifert W, et al. Allelic heterogeneity in the COH1 gene explains clinical variability in Cohen syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:138–145. doi: 10.1086/422219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo I, Shimizu A, Asakawa S, et al. COH1 analysis and linkage study in two Japanese families with Cohen syndrome. Clin Genet. 2004;67:270–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mochida GH, Rajab A, Eyaid W, et al. Broader geographical spectrum of Cohen syndrome due to COH1 mutations. J Med Genet. 2004;41:e87. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.014779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert W, Holder-Espinasse M, Spranger S, et al. Mutational spectrum of COH1 and clinical heterogeneity in Cohen syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43:e22. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.039867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryns JP, Legius E, Devriendt K, et al. Cohen syndrome: the clinical symptoms and stigmata at a young age. Clin Genet. 1996;49:237–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1996.tb03780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Chehadeh S, Aral B, Gigot N, et al. Search for the best indicators for the presence of a VPS13B gene mutation and confirmation of diagnostic criteria in a series of 34 patients genotyped for suspected Cohen syndrome. J Med Genet. 2010;47:549–553. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.075028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivitie-Kallio S, Larsen A, Kajasto K, Norio R. Neurological and psychological findings in patients with Cohen syndrome: a study of 18 patients aged 11 months to 57 years. Neuropediatrics. 1999;30:181–189. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn D, Krebsová A, Kunze J, Reis A. Homozygosity mapping in a family with microcephaly, mental retardation, and short stature to a Cohen syndrome region on 8q21.3-8q22.1: redefining a clinical entity. Am J Med Genet. 2000;92:285–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler KE, Biswas S, Lloyd IC, et al. The ophthalmic findings in Cohen syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1395–1398. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.12.1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzaki E, Pescucci C, Uliana V, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of Italian patients affected by Cohen syndrome. J Hum Genet. 2007;52:1011–1017. doi: 10.1007/s10038-007-0208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert W, Holder-Espinasse M, Kühnisch J, et al. Expanded mutational spectrum in Cohen syndrome, tissue expression, and transcript variants of COH1. Hum Mutat. 2009;30:E404–E420. doi: 10.1002/humu.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]