Abstract

Aim

To evaluate and compare the perceptions of Saudi dentists and lay people to altered smile features.

Methods

Thirty-six digital smile photographs with altered features were used. Altered features included the following: crown length, width, gingival level of the lateral incisors, gingival display, midline diastema, and upper midline shift. The photographs were presented to a sample of 30 dentists and 30 lay people with equal gender distribution. Each participant rated each picture with a visual analogue scale, which ranged from 0 (very unattractive) to 100 (very attractive).

Results

Dentists were more critical than lay people when evaluating symmetrical crown length discrepancies. Compared to lay people, Saudi dentists gave lower ratings to a crown length discrepancy of >2 mm (P < 0.001), crown width discrepancy of ⩾2 mm (P < 0.05), change in gingiva to lip distance of ⩾2 mm (P < 0.01), and midline deviation of >1 mm (P < 0.01). There was no significant difference between dentists and lay people towards alterations in the gingival level of the lateral incisors or towards a space between the central incisors. No significant sex difference was seen across the groups.

Conclusion

In this sample, Saudi dentists gave significantly lower attractiveness scores to crown length and crown width discrepancies, midline deviations, and changes in gingiva to lip distance compared to Saudi lay people.

Keywords: Saudi dentists, Smile esthetics, Perception, Lay people

1. Introduction

Facial attractiveness is defined by the smile of an individual, which is a valuable method for influencing people. Smile analysis is an integral part of the overall facial analysis carried out by dentists, orthodontists, and maxillofacial surgeons. An individual smile is defined as the dynamic and static relationship of the dentition and supporting structures to the facial soft tissues. A smile analysis includes the amount of the incisors and gingiva show upon smiling, the smile arc (parallelism between the maxillary incisal edges and the lower lip), tooth proportions, gingival height and contours, relationship between the dental midline and facial midline, and tooth shade and color.

Normally upon smiling, the entire upper incisor is seen. Some display of the gingiva is considered acceptable. A display of the upper incisors of <75% is considered unacceptable (Kokich et al., 1999). Maxillary tooth width proportions provide an example of the golden proportion. The width of the lateral incisor should be around 62% of the width of the central incisor. The maxillary dental midline should coincide with the soft tissue facial midline (Johnston et al., 1999). However, it can be difficult to assess the relationship of the dental midline to the facial midline. One common method for this assessment is to use a dental floss through the facial midline. Another method is to assess the relationship of the dental midline to the philtrum of the upper lip. A midline discrepancy of <2 mm between the maxillary dental midline and the facial midline is considered to be acceptable (Beyer and Lindauer, 1998; Cardash et al., 2003). However, any maxillary incisal cant (unparallel relationship between the maxillary incisors) is easily perceived by dental professionals and lay people (Kokich et al., 1999).

Professional and observant individuals are able to detect features that are out of balance or harmony (Miller, 1989). For orthodontic treatment decisions, it is essential to understand the threshold of what a community considers acceptable in terms of abnormal smile features. The perceptions of aesthetic dental alterations by lay people and professionals have been evaluated (Kokich et al., 1999; Flores et al., 2004; LaVacca et al., 2005; Moore et al., 2005). Asymmetric alterations make teeth unattractive to dentists and lay people alike (Kokich et al., 2006). The perception of facial and dental esthetics has been evaluated with the visual analogue scale (VAS), which is considered to be an easy and reliable method (Talic and Al-Shakhs, 2008).

The aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the perceptions of Saudi dentists and lay people to altered smile features.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Sample

Two judging groups (30 Saudi dentists and 30 Saudi nondentists) were asked to participate in this study. The nondentist group represented Saudi lay people. The selection of the judges was random. The lay people group had different backgrounds, with an age range of 20–40 years. The dental group included general practitioners, with an age range of 24–35 years. The male to female ratio was equal in both groups. A consent form was signed by the participants in the study, and ethical approval was given by the College of Dentistry Research Center.

2.2. Variables and measurements

Thirty-six digital photographs were used in this study. The photographs showed the smile alone, excluding other facial structures, to minimize any distracting variables. The smile features in the photographs were digitally altered by Adobe Photoshop software (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA). The alterations were intentionally created to resemble a smile aesthetic discrepancy.

The photographs were grouped into six sets, each representing an altered smile feature, with alteration increments ranging from 0.5 to 1 mm. The altered features were as follows: (1) crown length (CL), (2) level of the gingival margins of the lateral incisors, (3) gingiva show, (4) crown width, (5) maxillary midline shift, and (6) midline diastema. The alterations are described in detail in Sections 2.2.1 through 2.2.6.

The sets were arranged in order, but the incremental changes were not sequenced. During the survey, the photographs were coded by the authors with serial numbers from 1 to 36. Photographs displaying the incremental changes were arranged and displayed randomly.

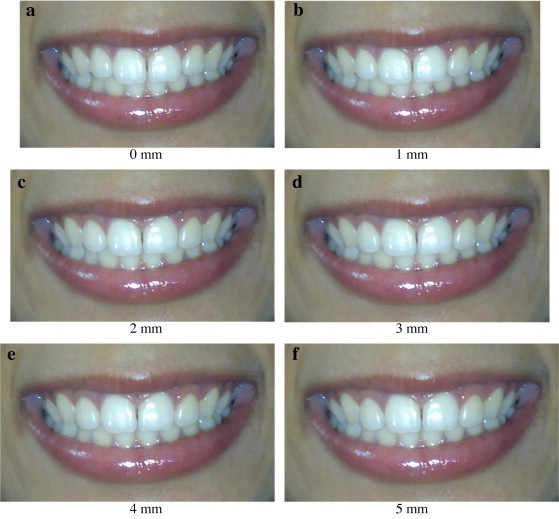

2.2.1. Crown length (Fig. 1)

Figure 1.

Photographs showing alteration to the crown length of the central incisors. The alteration was made to the maxillary central incisors, using the incisal edge as a reference point to the highest point of the gingival margin. (a) Central incisor crown length alteration by 0.5 mm increment; (b) 1 mm increment; (c) 1.5 mm increment; (d) 2 mm increment; (e) 2.5 mm and (f) 3 mm increment.

The CL of the maxillary central incisors was increased by 0.5 mm. The incisal edge was used as a reference point for the highest point of the gingival margin.

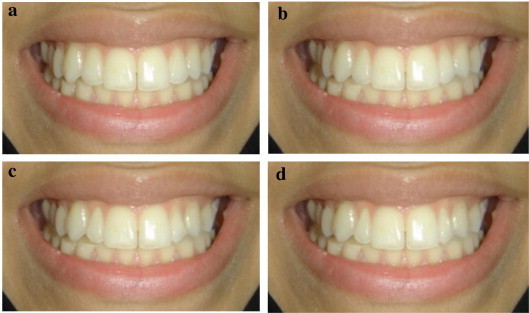

2.2.2. Level of the gingival margins of the lateral incisors (Fig. 2)

Figure 2.

Photographs showing alteration to the vertical height of the ginigival margins of the maxillary lateral incisors in relation to the gingival height of the central incisors. (a) no alteration; (b) 1 mm alteration; (c) 2 mm; (d) 3 mm; (e) 4 mm and (f) 5 mm.

The vertical position of the gingiva of the maxillary lateral incisors was increased by 1 mm relative to the adjacent central incisor.

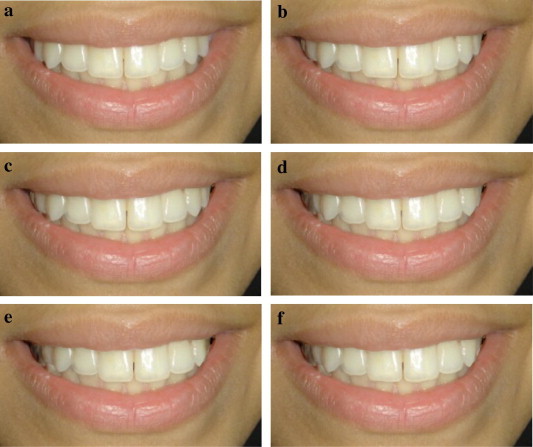

2.2.3. Gingiva show (Fig. 3)

Figure 3.

Photographs showing alteration of the gingiva to lip relation (Gingival show). Alterations were based on the relation of the upper lip with the gingival margin of the maxillary incisors. (a) No change; (b) 1 mm increase in gingival show; (c) 2 mm; (d) 3 mm; (e) 4 mm and (f) 5 mm.

The gingiva to lip margin level (gingival show) was increased by 1 mm, to create a “gummy” smile. Alterations were based on the relationship of the upper lip with the gingival margin of the maxillary incisors.

2.2.4. Crown width (Fig. 4)

Figure 4.

Photographs showing alterations to maxillary lateral incisors crown width. The mesio-distal width of the maxillary lateral incisors was decreased by an increment of 1 mm. (a) 1 mm decrease in the width of the maxillary lateral incisors; (b) 2 mm; (c) 3 mm and (d) 4 mm.

Symmetrical crown width alterations were made to the maxillary lateral incisors. The incisal edge was kept at the same level. The alteration was limited to the mesio-distal width of the lateral incisors, which was decreased by 1 mm.

2.2.5. Midline shift (Fig. 5)

Figure 5.

Photographs showing alterations to maxillary dental midline in relation to the philtrum of the lip. The alterations were done with 1 mm increment. (a) No midline deviation; (b) 1 mm midline deviation to the left; (c) 2 mm deviation; (d) 3 mm deviation; (e) 4 mm deviation and (f) 5 mm deviation.

A maxillary dental midline shift was made, while the lower midline and the lip cupid bow were fixed and used as a reference. A 1-mm increment was used to shift the maxillary midline to the right of the patient.

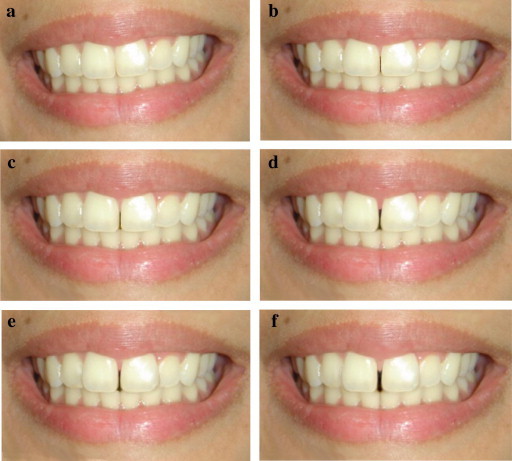

2.2.6. Midline diastema (Fig. 6)

Figure 6.

Photographs showing alteration of a midline diastema. The alterations were done by an increment of 0.5 mm. (a) No alteration; (b) 0.5 mm midline diastema; (c) 1 mm diastema; (d) 1.5 mm diastema; (e) 2 mm diastema and (f) 2.5 mm diastema.

A midline diastema was introduced between the maxillary central incisors by a 0.5-mm increment measured from the interproximal contact point of the central incisors.

2.3. Visual analogue scale

An evaluation form containing the VAS under the photographs was distributed to both judging groups and used to rate the smile esthetics. The VAS was 100 mm in length. The left end of the scale was labelled as “very unattractive” and was represented by the number zero. The right end of the scale was labelled “very attractive” and was represented by the number 100. Each judge was asked to place a mark along the VAS to rate his/her perception of dental aesthetics. Each mark on the VAS was measured with a caliper and recorded.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The data were analysed by Student’s t-test to identify any statistically significant differences in the perception of dentists and lay people to altered smile aesthetics. The confidence level was set at P < 0.05. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to investigate a possible association between sex and the perception towards smile discrepancies.

3. Results

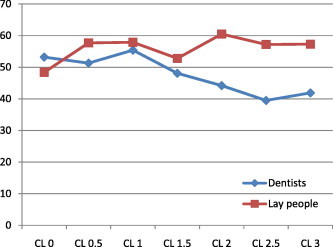

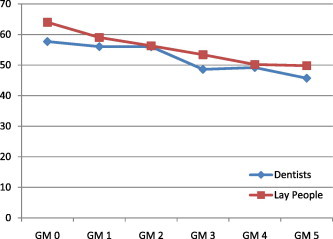

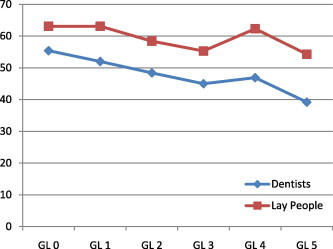

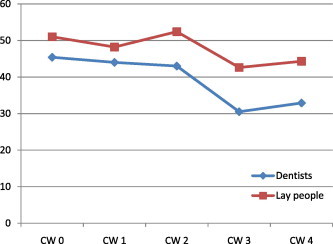

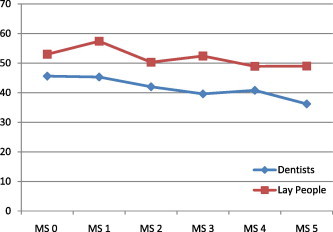

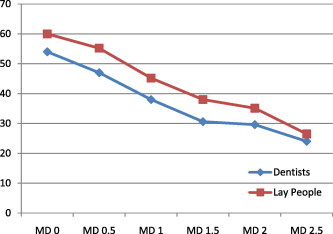

A comparison of the perceptions of Saudi dentists and lay people to altered smile aesthetics showed that dentists were more critical than lay people when evaluating symmetric CL discrepancies. There was no significant difference between dentists and lay people when the CL discrepancy was <2 mm. However, dentists gave lower VAS ratings than lay people to CL discrepancies of >2 mm (P < 0.001) (Table 1; Fig. 7). Ratings by dentists were lower than those by lay people when assessing alterations of the lateral incisor gingival margins. However, this difference was not statistically significant (Table 2; Fig. 8). The perceptions of dentists and lay people to gingiva show were not significantly different at the 0-mm level. However, dentists gave lower ratings than lay people when the gingiva to lip margin was >1 mm (P < 0.01) (Table 3; Fig. 9). Dentists gave lower ratings than lay people when the crown width discrepancy was ⩾2 mm (P < 0.05) (Table 4; Fig. 10). Saudi dentists gave lower ratings than lay people to a midline deviation >1 mm (P < 0.01) (Table 5; Fig. 11). A small amount of space between the maxillary central incisors was rated as unattractive by both dentists and lay people, with no significant difference between the two groups (Table 6; Fig. 12). No significant sex difference was seen across the groups. However, females tended to give slightly higher ratings for most of the discrepancies.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of VAS rating by dentists and lay people to crown length discrepancy. (CL: Crown length in mm).

| Variable | Dentists | Lay people | t-test | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CL 0 | 53.2 ± 25.5 | 48.4 ± 28.6 | .957 | .340 NS |

| CL 0.5 | 51.3 ± 23.2 | 57.7 ± 29 | −1.32 | .189 NS |

| CL 1 | 55.4 ± 22.1 | 57.9 ± 26.3 | −.553 | .581 NS |

| CL 1.5 | 48.1 ± 21.9 | 52.8 ± 22.9 | −1.15 | .252 NS |

| CL 2 | 44.2 ± 18.6 | 60.5 ± 24.7 | −4.08 | .000⁎⁎⁎ |

| CL 2.5 | 39.5 ± 22.4 | 57.2 ± 25.4 | −4.06 | .000⁎⁎⁎ |

| CL 3 | 41.9 ± 24.6 | 57.3 ± 25.7 | −3.34 | .001⁎⁎ |

NS: Not significant.

∗p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Figure 7.

Line graph showing the mean rating of the crown length discrepancy by dentist and lay people. (CL: Crown length in mm).

Table 2.

Means and standard deviations of rating by dentists and lay people to altered gingival margin level discrepancy. (GM: Gingival margin in mm).

| Dentists | Lay people | t-test | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM 0 | 57.7 ± 18.8 | 64 ± 27.5 | −1.433 | .154 NS |

| GM 1 | 56.05 ± 20.8 | 59.03 ± 23.6 | −.734 | .464 NS |

| GM 2 | 56 ± 20.9 | 56.3 ± 26.9 | −.083 | .934 NS |

| GM 3 | 48.6 ± 21.2 | 53.4 ± 23.9 | −1.151 | .252 NS |

| GM 4 | 49.2 ± 21.7 | 50.2 ± 24.4 | −.221 | .825 NS |

| GM 5 | 45.7 ± 22.6 | 49.8 ± 26.8 | −.910 | .364 NS |

NS: Not significant.

Figure 8.

Line graph showing the mean rating of the gingival margin level discrepancy by dentist and lay people. (GM: Gingival margin in mm).

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations of the rating by dentists and lay people to the gingival to lip margin discrepancy. (GL: Gingival to lip margin in mm).

| Dentists | Lay people | t-test | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GL 0 | 55.4 ± 23.9 | 63.1 ± 24.6 | −1.750 | .083 NS |

| GL 1 | 52 ± 23.4 | 63.1 ± 22.8 | −2.704 | .008⁎⁎ |

| GL 2 | 48.4 ± 23.8 | 58.4 ± 21.9 | −2.382 | .019⁎ |

| GL 3 | 45 ± 23.6 | 55.3 ± 25.6 | −2.300 | .023⁎ |

| GL 4 | 46.9 ± 24.2 | 62.3 ± 25 | −3.413 | .001⁎⁎ |

| GL 5 | 39.2 ± 23.9 | 54.3 ± 27.8 | −3.189 | .002⁎⁎ |

NS: Not significant.

∗∗∗p < 0.001.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Figure 9.

Line graph showing the mean rating of the gingival to lip margin discrepancy by dentist and lay people. (GL: Gingival to lip margin in mm).

Table 4.

Means and standard deviations of rating by dentists and lay people to crown width discrepancy. (CW: Crown width in mm).

| Dentists | Lay people | t-test | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CW 0 | 45.4 ± 24.1 | 51 ± 25.4 | −1.232 | .221 NS |

| CW 1 | 44 ± 21.6 | 48.2 ± 25.8 | −.976 | .331 NS |

| CW 2 | 43 ± 23 | 52.4 ± 23.7 | −2.212 | .029⁎ |

| CW 3 | 30.5 ± 21.5 | 42.6 ± 25.4 | −2.821 | .006⁎⁎ |

| CW 4 | 32.9 ± 23.5 | 44.3 ± 26.1 | −2.497 | .014⁎ |

NS: Not significant.

∗∗∗p < 0.001.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

Figure 10.

Line graph showing the mean rating of the crown width discrepancy by dentist and lay people. (CW: Crown width in mm).

Table 5.

Means and standard deviations of rating by dentists and lay people to midline shift discrepancy. (MS: Midline shift in mm).

| Dentists | Lay people | t-test | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MS 0 | 45.6 ± 26 | 53 ± 25.4 | −1.505 | .135 NS |

| MS 1 | 45.3 ± 24.2 | 57.4 ± 24.2 | −2.736 | .007⁎⁎ |

| MS 2 | 42 ± 24 | 50.3 ± 26 | −1.858 | .066 NS |

| MS 3 | 39.6 ± 23 | 52.4 ± 27.1 | −2.787 | .006⁎⁎ |

| MS 4 | 40.8 ± 22.6 | 48.9 ± 24.2 | −1.886 | .062 NS |

| MS 5 | 36.2 ± 20.9 | 49 ± 24.7 | −2.953 | .004⁎⁎ |

NS: Not significant.

∗p < 0.05.

∗∗∗p < 0.001.

p < 0.01.

Figure 11.

Line graph showing the mean rating of the midline shift discrepancy by dentist and lay people. (MS: Midline shift in mm).

Table 6.

Means and standard deviations of rating by dentists and lay people to midline diastema discrepancy. (MD: Midline diastema in mm).

| Dentists | Lay people | t-test | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD 0 | 54 ± 25.1 | 60 ± 23.7 | −1.344 | .181 NS |

| MD 0.5 | 47 ± 23 | 55.2 ± 24.2 | −1.920 | .057 NS |

| MD 1 | 38 ± 22.3 | 45.2 ± 25.9 | −1.678 | .096 NS |

| MD 1.5 | 30.6 ± 21.1 | 38 ± 26 | −1.589 | .115 NS |

| MD 2 | 29.6 ± 21.4 | 35.1 ± 24.6 | −1.300 | .196 NS |

| MD 2.5 | 24 ± 20.2 | 26.5 ± 22.6 | −.639 | .524 NS |

NS: Not significant.

Figure 12.

Line graph showing the mean rating of the midline diastema discrepancy by dentist and lay people. (MD: Midline diastema in mm).

4. Discussion

In this study, the threshold for CL discrepancy by Saudi dentists and lay people was ⩾2 mm, which is considered to be a low threshold. These findings are comparable to those of Kokich et al. (1999), who evaluated the perceptions of dental professionals and lay people to bilateral CL alterations. In that study, the threshold for unattractiveness was 1.0 mm for orthodontists, 1.5 mm for general dentists, and 2.0 mm for lay people. The length of the maxillary incisors should be greater than their mesio-distal width. Therefore, incisors should exhibit a rectangular shape in the gingival-incisor dimension rather than a square shape. This golden proportion could be achieved by orthodontic intrusion followed by composite build-ups, veneers, or even porcelain crowns. In some cases, aesthetic gingivectomy may be considered as a treatment option (Kokich, 1996; Kokich and Spear, 1997).

Previous studies have reported prevalence rates of small (peg-shaped) lateral incisors ranging from 0.37% to 4% in different regions of Saudi Arabia (Al Emran, 1990; Salem, 1989). In the present study, Saudi dentists gave lower ratings than lay people when the crown width discrepancy was ⩾1 mm (P < 0.05). This threshold is comparable to the threshold found by a previous study, which reported that general dentists were able to detect a lateral incisor crown width narrowing of 3 mm, whereas lay people did not notice a change until the lateral incisor width was narrowed by 2 mm. Therefore, dentists appear to be more sensitive to smaller peg-shaped lateral incisors. To have a normal aesthetic smile, the lateral incisor width should be two-thirds the width of the central incisor, or it should follow the golden proportion of 0.618 of the width of the central incisor. If a patient has a small peg-shaped lateral incisor, composite build-up or ceramic veneers may be used to meet the golden proportion of an aesthetic smile.

In this study, the ratings by Saudi dentists were slightly lower when assessing lateral incisor gingival level alterations as compared to Saudi lay people. However, this difference was not statistically significant. This finding is in agreement with a previous study that showed that symmetrical gingival alterations were not detected by orthodontists, dentists, or lay people (Kokich et al., 1999). Normally, the entire upper incisor is seen upon smiling. A gingival display of 1–2 mm is considered acceptable (Chiche and Pinault, 1994). Saudi dentists and lay people perceived a change in attractiveness when the gingiva to lip distance was ⩾1 mm. This finding is in disagreement with a previous study that showed increased gingiva to lip distance was not noticeable by American dentists and lay people until it was at least 4 mm (Kokich et al., 1999). Saudi dentists and lay people appear to have a lower threshold to excessive gingiva show upon smiling. The rating of Saudi dentists and lay people was comparable to that of American orthodontists, who rated 2 mm of gingival show as excessive.

The prevalence rates of midline diastema and midline discrepancy in Saudis were previously reported to be 32.8% and 30.7%, respectively (Al-Balkhi and Zahrani, 1994). A small amount of space between the maxillary central incisors was rated as unattractive by both Saudi dentists and lay people. However, there was no significant difference in the ratings of Saudi dentists and lay people to a space between the central incisors.

Saudi dentists gave lower scores than lay people to a midline deviation of >1 mm (P < 0.01). These findings are comparable to the threshold reported by American dentists and lay people (Kokich et al., 1999). However, Saudi dentists were more sensitive to midline deviations. Orthodontists should only accept a maxillary midline deviation if the deviation is vertical without any cant (angulation) in the maxillary anterior teeth. No significant sex difference was seen across the groups in the perception of symmetrical smile alterations. This observation confirms that aesthetics is viewed by an individual regardless of his or her gender.

The findings of the present study may be utilized by dentists and orthodontists when making treatment decisions, particularly decisions influenced by the thresholds of Saudi lay people to altered smile features. Future studies are needed to examine the perceptions of orthodontists to altered smile aesthetics and of Saudi dentists, lay people, and orthodontists to asymmetric alterations.

5. Conclusions

-

•

The sample of Saudi dentists examined in this study was more critical than lay people when evaluating symmetric CL discrepancies. However, lay people significantly perceived CL discrepancies of >2 mm.

-

•

The sample of Saudi dentists gave significantly lower VAS ratings than lay people when the crown width discrepancy was ⩾2 mm.

-

•

The VAS ratings of Saudi dentists were slightly lower than those of lay people when assessing lateral incisor gingival/incisal level alterations.

-

•

When the gingiva to lip margin discrepancy was >1 mm, dentists gave significantly lower VAS ratings than lay people.

-

•

A small amount of space between the maxillary central incisors was rated as unattractive by both dentists and lay people, with no significant difference between the groups.

-

•

Compared to Saudi lay people, Saudi dentists gave significantly lower VAS ratings to midline deviations of >1 mm.

-

•

Females tended to give slightly higher ratings for most of the discrepancies.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Al-Balkhi K., Zahrani A. The pattern of malocclusions in Saudi Arabian patients attending for orthodontic treatment at the College of Dentistry, King Saud University. Riyadh Saudi Dent. J. 1994;6:138–144. [Google Scholar]

- Al Emran S. Prevalence of hypodontia and developmental malformation of permanent teeth in Saudi Arabian school children. Br. J. Orthod. 1990;17:115–118. doi: 10.1179/bjo.17.2.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer J., Lindauer S. Evaluation of dental midline position. Semin. Orthod. 1998;4:146–152. doi: 10.1016/s1073-8746(98)80016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardash H., Ormanier Z., Laufer B. Observable deviation of the facial and anterior tooth midlines. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003;89:282–285. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2003.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiche G., Pinault A. Quintessence; Chicago: 1994. Esthetics of Anterior Fixed Prosthodontics. [Google Scholar]

- Flores C., Silva E., Barriga M.I., Lagravere M.O., Major P. Lay person’s perception of smile aesthetics in dental and facial views. J. Orthod. 2004;31:204–209. doi: 10.1179/146531204225022416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston D., Burden D., Stevenson M. The influence of dental to facial midline discrepancies on dental attractiveness ratings. Eur. J. Orthod. 1999;21:517–522. doi: 10.1093/ejo/21.5.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokich V.G. Esthetics: the orthodontic-periodontic restorative connection. Semin. Orthod. 1996;2:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s1073-8746(96)80036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokich V.G., Spear F.M. Guidelines for managing the orthodontic restorative patient. Semin. Orthod. 1997;3:3–20. doi: 10.1016/s1073-8746(97)80036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokich V., Kiyak H.A., Shapiro P.A. Comparing the perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental esthetics. J. Esthet. Dent. 1999;11:311–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.1999.tb00414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokich V.O., Kokich V.G., Kiyak H. Perceptions of dental professionals and laypersons to altered dental esthetics: asymmetric and symmetric situations. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;130:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVacca M.I., Tarnow D.P., Cisneros G.I. Interdental papilla length and the perception of aesthetics. Pract. Proced. Aesthet. Dent. 2005;17:405–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller C.J. The smile line as a guide to anterior esthetics. Dent. Clin. North. Am. 1989;33:157–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore T., Southard K.A., Casko J.S., Qian F., Southard T.E. Buccal corridors and smile esthetics. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial Orthop. 2005;127:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.ajodo.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salem G. Prevalence of selected dental anomalies in Saudi children from Gizan. Com. Dent. Oral. Epid. 1989;17:162–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1989.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talic N., Al-Shakhs M. Perception of facial profile attractiveness by a Saudi sample. Saudi Dent. J. 2008;20:17–23. [Google Scholar]