Abstract

Hydatid cysts develop most frequently in the liver and lungs, but they are occasionally found in other organs. Hydatid cysts in the axillary space are an extremely rare event in areas where the disease is endemic, and are still common in many countries, including Turkey. A 73-year-old man presented to our clinic with a painful axillary mass. Thoracoabdominal computed tomography revealed multilocular cystic masses localized in the left axillary space, with minimal invasion of the peripheral soft tissue and no pulmonary or hepatic involvement. An echinococcal indirect hemagglutination test was negative. The masses were dissected through their stalks and removed completely. Macroscopic and microscopic examination of the specimens confirmed hydatid cysts. This case report demonstrates that hydatid cysts should be considered as a possible cause for palpable lesions in the axillary region or chest wall, especially in endemic locations.

Keywords: Axillary space, Unusual location, Echinococcosis, Hydatid cyst

Echinococcal disease is caused by infection with the metacestode stage of Echinococcus tapeworms of the family Taeniidae. Four species of Echinococcus cause infection in humans; Echinococcus granulosus and E. alveolaris are the most common, causing cystic and alveolar echinococcosis, respectively. The primary carriers are dogs and wolves, whereas the intermediate hosts are sheep, cattle, and deer. Humans, who are accidental hosts and do not play a role in the biological cycle, are infected by ingesting ova from soil or water contaminated by the feces of dogs.1–4 When ingested, the eggs lose their enveloping layer in the stomach and release embryos. The embryos pass through the intestinal mucosa and reach the liver through the portal vein, where most larvae become trapped and encysted. Some larvae may reach the lungs, and occasionally, may pass through the capillary filter of the liver and lungs and enter the circulation.5

Cystic echinococcosis (hydatid cysts) are common in societies in which agriculture and raising animals are common, and hydatid disease continues to be a serious public health problem in many countries, including Turkey. Hydatid cysts may develop in any organ of the body, but occur most frequently in the liver (50%–80%) and lungs (15%–47%), and occasionally in the spleen, kidney, pancreas, intraperitoneal space, heart, ovaries, prostate, incision scar, retroperitoneal space, thyroid, vesica urinaria, orbita, head and neck, chest wall, brain, musculoskeletal and soft tissue, breast, and axillary space.1–4,6–12 Axillary hydatid cysts are extremely rare, with only a few cases reported in the English language literature.6–11 We present a case of hydatid cyst in the axillary space due to its outstanding rarity and clinical confusion with other causes of axillary masses.

Case Report

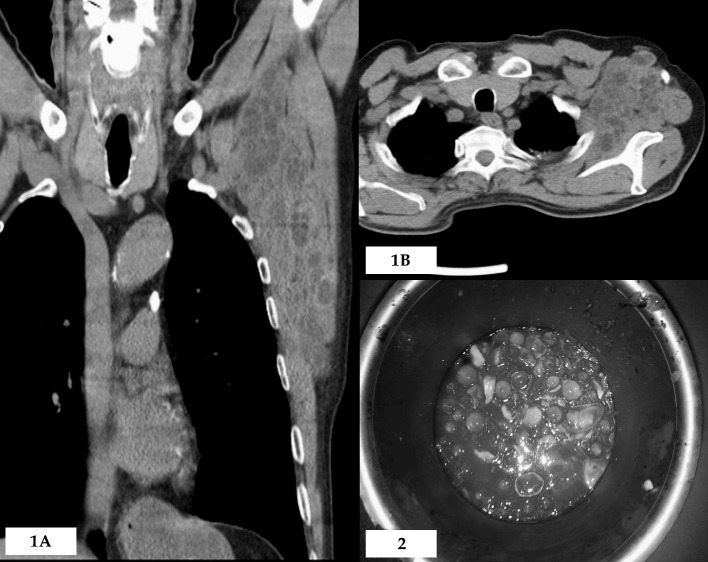

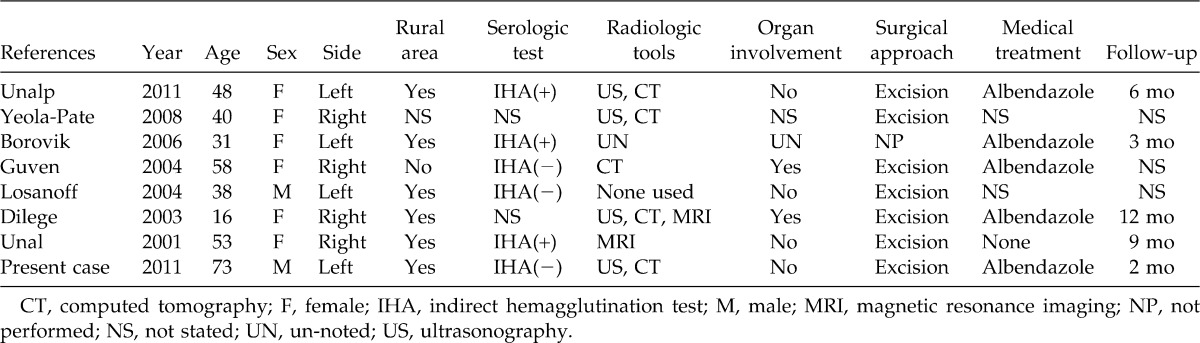

A 73-year-old man presented to our clinic complaining of pain and swelling in the left armpit. A dog bit his left arm 30 years ago, and he underwent surgery twice in the left armpit, 25 and 15 years ago, respectively, as the swelling developed. The surgeon who performed the latest operation told him that the mass under the armpits was related to the hydatid disease. The patient had mentioned that he dealt with ranching and animal husbandry during a large part of his life and had a shepherd dog. Physical examination resulted in palpation of the masses. The masses formed a conglomerate structure that filled the left axilla completely, which were fixed to surrounding structures, and a large number of enlarged lymph nodes. Echinococcal indirect hemagglutination test (IHA) for Echinococcus granulosus was negative. Axillary ultrasonography was performed in the patient. The ultrasound image was consistent with a multiloculated hydatid cyst. Next, thoracoabdominal computed tomography (CT) was performed. In the CT scans, although no cystic lesions were found in the liver and lungs, a large number of hydatid cysts compatible with multiloculated lesions were seen in the left axilla, starting from the left axillary vein, and extending downward in front of the scapula (Fig. 1A and 1B). In addition, limits between these cystic lesions and the surrounding tissue were not clearly demarcated. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) had been planned for the patient, but because stents were placed in the coronary arteries 2 years ago, MRI could not be performed. The patient was given preoperatively 2 × 400 mg/d albendazole for 15 days. The patient was then scheduled for surgery. Under general anesthesia, the axillary space was accessed using an old incision. Because of the previous surgery, the axilla was depressed and approximately 15 cystic lesions (5–6 cm in diameter) were detected in the axilla. Some of these cysts extended from the axillary vein to the top of the axilla, whereas others extended downward from the front part of the scapular bone. All cysts were excised completely, including the surrounding fibrous tissue (Fig. 2). A drain was placed in the axillary space and surgery was completed. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was discharged 6 days after his operation and placed on a 4-week course of albendazole at 2 × 400 mg/d.

Figure 1.

Multidetector computed tomography (CT) images in different planes after contrast injection. (A) Coronal plane multidetector CT images show multilocular cystic lesions located between the axillary space and left chest wall. (B) Multilocular cystic lesions located in the left axillary space are seen in axial plane CT sections.

Fig. 2 Postoperative excised cyst showing daughter vesicles.

Discussion

Cystic echinococcosis may affect all organs, but mostly settles in the liver and lungs. This is as a result of the life cycle of the parasite. The liver is the first filter that meets the hepatic portal flow. Most of the larvae are retained here and the structure of the cyst is formed. Larvae that pass through the microvascular wall at the liver will reach the lungs. In 10%–20% of patients, the larvae can pass through the liver and lungs to the systemic circulation by means of the capillary system and settle in any tissues and organs.6,12 The larvae can also pass through the venous mesenteric lymph vessels by diffusion and settle in tissues and/or various intra-abdominal organs by transmural migration through the intestinal wall.12 The mechanism by which the parasitic larvae passes from the liver–lung capillary barrier to the systemic circulation, and how they determine which organ or tissue in which to settle, remains a controversial subject. In addition, although detection of atypical hydatid disease with atypical localization, together with the liver and lungs (secondary atypical) is easy to comprehend, atypical localization alone without hydatid disease in the liver and lung (primary atypical) is a separate subject of discussion. It is difficult to explain why larvae may directly pass through the intestinal system to the systemic circulation without going to the liver or without forming a liver cyst.

We do not have data on the means by which the larvae of echinococcosis reach/access the axillary space. Considering the anatomy of the axilla and its surrounding area, we can make some assumptions about how the hydatid cysts settle in the axillary space.

There is a rich lymphatic flow in the axillary space. Although it occurs rarely, larvae in the gastrointestinal tract may pass to the lymphatic circulation, and then settle in the space.

The axillary fossa has three edges: the front, rear, and interior edge, and the eight different muscle bundles that form these edges. Hydatid cysts that originate from these muscles and extend in an exophytic manner can grow toward the axillary space, leading to the formation of an axillary cyst. It is likely that the axillary hydatid disease in our patient developed in this manner.

The inner edge of the axillary fossa is directly adjacent to the thoracic wall. In this case, larval migration from the pulmonary system to the axillary space through the surrounding area is possible.

Based on a review of the English language literature using Google Scholar and PubMed databases, we identified 7 published studies related to axillary hydatidosis.6,11 These studies included a total of 7 patients, 6 women and 1 man, aged 16–58 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with axillary hydatid disease

Among the clinical signs to be considered in the differential diagnosis of axillary hydatid cysts, the foremost are conglomerate lymphadenopathies, granulomatous lymphadenitis, parasitic diseases, hematoma, abscess, lymphocele, breast cancer manifested in the form of axillary metastasis, soft tissue sarcomas, and other malignancies causing axillary metastasis.6 Differential diagnoses can be made by the combined evaluation of one or more options such as physical examination, history of disease, history of contact with animals, life history in endemic areas, travel history, ultrasonography, CT, MRI, serologic tests and histopathologic examination of biopsy material and permanent tissue, and the use of specific stains.9,13

There are many infectious diseases that cause cystic lesions in the axillary region, such as toxoplasmosis, filariasis, echinococcosis, cat-scratch disease, and tuberculosis. The type of animal host and the travel and life history in endemic areas provide very important clues to the identity of the disease.9

Radiologically, there are no differences between the typical image of the axillary hydatid cysts and the cysts at other locations.1,9 Although the diagnosis of hydatid cyst is often based on radiologic imaging, a definitive diagnosis should always be confirmed histopathologically.6,13

Latex agglutination test, IHA, indirect immunofluorescence test, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), Western blotting, and polymerase chain reaction are among the most commonly used serologic tests. ELISA and IHA tests provide the best results for recurrence during the postoperative period. Although higher sensitivity, specificity, and efficacy can be obtained with ELISA, in practice, the most frequently used test is IHA because it is cheaper and easier to use.

Currently, the most effective treatment for hydatid disease located in soft tissue is still surgery. The main purpose of surgery is to prevent complications such as compression of surrounding structures, infection, or cyst rupture. Total cystectomy with fibrous adventitia, which allows for the removal of all parasitic elements without spillage of the contents of the cyst, is curative treatment for soft tissue hydatidosis, including axillary hydatid cysts. Soft tissue cysts can be easily ruptured. Therefore, rupture of the cyst must be avoided to prevent recurrence.6,11

Based on our own experience, regardless of the location, all patients with hydatid cyst for which surgery is planned should be given albendazole prophylactically 2 × 400 mg/d for at least 2 weeks.3 No postoperative medical treatment is needed for patients who had total cystectomy. In cases with cyst rupture or with other cysts in different locations, treatment should be continued for 2 months during the postoperative period.

References

- 1.Akbulut S, Senol A, Ekin A, Bakir S, Bayan K, Dursun M. Primary retroperitoneal hydatid cyst: report of 2 cases and review of 41 published cases. Int Surg. 2010;95(3):189–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yagmur Y, Akbulut S. Epidemiology of hydatid disease. Turkiye Klinikleri J Gen Surg-Special Topics. 2010;3(2):6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akbulut S, Senol A, Sezgin A, Cakabay B, Dursun M, Satici O. Radical vs conservative surgery for hydatid liver cysts: experience from single center. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16(8):953–959. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i8.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang G, Wang X, Mao Y, Liu W. Case report of primary retroperitoneal hydatid cyst. Parasitol Int. 2011;60(3):333–334. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guven G.S, Simsek H, Cakir B, Akhan O, Abbasoglu O. A hydatid cyst presenting as an axillary mass. Am J Med. 2004;117(5):363–364. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unalp H.R, Kamer E, Rezanko T, Kilic O, Tunakan M, Onal M.A. Primary hydatid cyst of the axillary region: a case report. Balkan Med J. 2011;28(2):209–211. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeola-Pate M, Banode P.J, Bhole A.M, Golhar K.B, Shahapurkar V.V, Joharapurkar S.R. Different locations of hydatid cysts: case illustrations and literature review. Infect Dis Clin Pract. 2008;16(6):379Y384. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borovik A, Massasso D, Gibson K. Axillary hydatid disease. MJA. 2006;184(11):585. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Losanoff J.E, Richman B.W, Jones J.W. Primary hydatid cyst of the axilla. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(5):393–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.03002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dilege S, Aksoy M, Okan I, Toker A, Kalayci G, Demiryont M. Hydatid cystic disease of the soft tissues with pulmonary and hepatic involvement: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33(1):69–71. doi: 10.1007/s005950300014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Unal A.E, Ulukent S.C, Bayar S, Demirkan A, Akgül H. Primary hydatid cyst of the axillary region: report of a case. Surg Today. 2001;31(9):803–805. doi: 10.1007/s005950170051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Versaci A, Scuderi G, Rosato A, Angiò L.G, Oliva G, Sfuncia G, et al. Rare localizations of echinococcosis: personal experience. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75(11):986–991. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bal N, Kocer N.E, Arpaci R, Ezer A, Kayaselcuk F. Uncommon locations of hydatid cyst. Saudi Med J. 2008;29(7):1004–1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]