Abstract

Actinomycosis is an uncommon, chronic, granulomatous disease that can be mistaken for a malignant tumor. Abdominopelvic actinomycosis constitutes about 20% of all actinomycosis cases and may mimic malignancy, tuberculosis, or other abdominopelvic inflammatory diseases. This condition is more prevalent in women who use an intrauterine device. We treated a 44-year-old woman who presented with vaginal discharge, right flank pain, dysuria, and difficulty with defecation. She had anorexia and weight loss (8 kg) during the previous 2 months and had a history of intrauterine device use for 12 years. Clinical, radiologic, and endoscopic examinations revealed a rectal mass and right hydronephrosis. Rectal biopsy showed nonspecific colitis. Laparotomy showed a mass that was invading and obstructing the pelvic orifice. Surgery included total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, appendectomy, low anterior resection, and Hartmann colostomy. Histopathologic evaluation of surgical specimens showed actinomycosis originating from the tubo-ovarian structures and invading the rectal wall. The patient was placed on penicillin for 6 months, and then had closure of the colostomy with no complication.

Keywords: Abdominopelvic actinomycosis, Intrauterine device, Rectum, Tuboovarian structure, Hydronephrosis

Actinomyces species are gram-positive, nonmotile, unencapsulated, nonspore-forming, anaerobic bacteria that colonize the normal flora of the oral cavity, gastrointestinal system, and female genital tract.1 Actinomycosis is a chronic progressive suppurative disease characterized by the formation of multiple abscesses, draining sinuses, abundant granulation tissue, and dense fibrous tissue.2–4 Any disease or process that causes a breach in the protective mucosa, such as perforation of a viscus, surgery, trauma, or use of an intrauterine device (IUD), can be complicated by the proliferation of Actinomyces.4,5 Pelvic actinomycosis has recently become more prevalent and is associated almost exclusively with women who use IUDs. Diagnosing abdominopelvic actinomycosis preoperatively presents a challenge to the clinician because of the rarity and clinical variety of this condition. Abdominopelvic actinomycosis may mimic a neoplasm because of similar physical findings, clinical course, and radiographic changes. A colon carcinoma often is the provisional diagnosis before the identification of Actinomyces.6 We treated a patient who had abdominopelvic actinomycosis and presented with right hydronephrosis and a rectal mass.

Case Report

A 44-year-old woman was admitted to a urology outpatient clinic with complaints of pain in the right flank, dysuria, weight loss, and vaginal discharge. She had been married when she was aged 19 years and she gave birth to 5 children. After the fifth birth, she used a copper IUD for 12 years. She reached menopause when she was aged 42 years and she had the copper IUD removed 1 year before menopause. She developed groin pain 4 months before presentation, associated with incomplete bowel evacuation during defecation, and she had weight loss (8 kg) during the 2 months before presentation. Laboratory tests showed blood urea nitrogen, 22 mg/dL; creatinine, 1.87 mg/dL; hemoglobin, 10.7 g/dL; and white blood cell count, 19 700/µL. The results of other blood biochemical analyses and tumor marker levels were normal. Urinary ultrasonography and intravenous pyelography showed right grade 2 to 3 hydronephrosis, and a double J stent was inserted into the right ureter. The patient had persistent pelvic pain and was referred to the obstetrics and gynecology outpatient clinic for further evaluation. Gynecologic examination and vaginal ultrasonography showed a mass lesion in the right ovarian region and findings compatible with pelvic inflammatory disease. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging showed intense signal adjacent to a 3- × 2-cm cystic lesion in the right ovarian region lodge, which had the appearance of a dermoid cyst. The right ureteral double J stent was extracted during the first month of follow-up, and she had ureteral balloon dilatation.

The patient was referred to the general surgery outpatient clinic for defecation-related complaints. Digital rectal examination revealed nothing remarkable except for tenderness on palpation. Colonoscopy showed a mass in the rectum, located 10 to 15 cm from the anal verge, that obstructed the lumen in a crescentic manner and barely permitted the passage of the colonoscope. Biopsy specimens obtained from the mass were stained with CD3 and CD20 and showed chronic inflammation. The provisional diagnosis of a rectal tumor was made because of the presence of hydroureteronephrosis, a lumen-narrowing mass in the rectum, and history of weight loss.

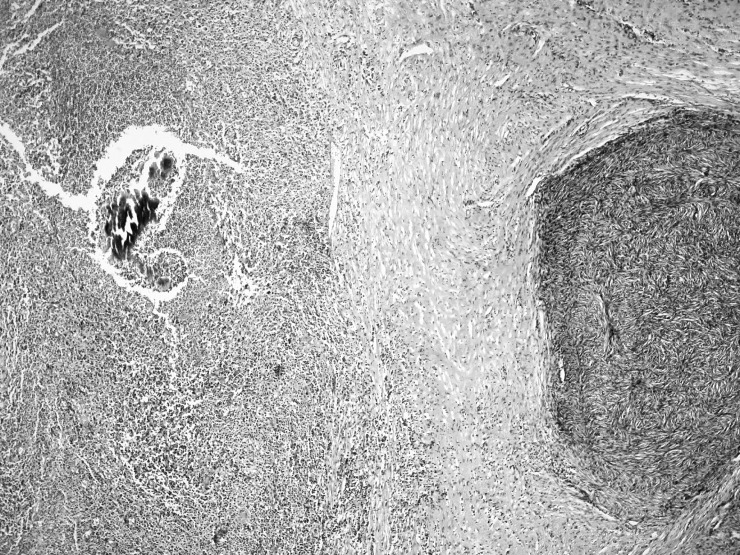

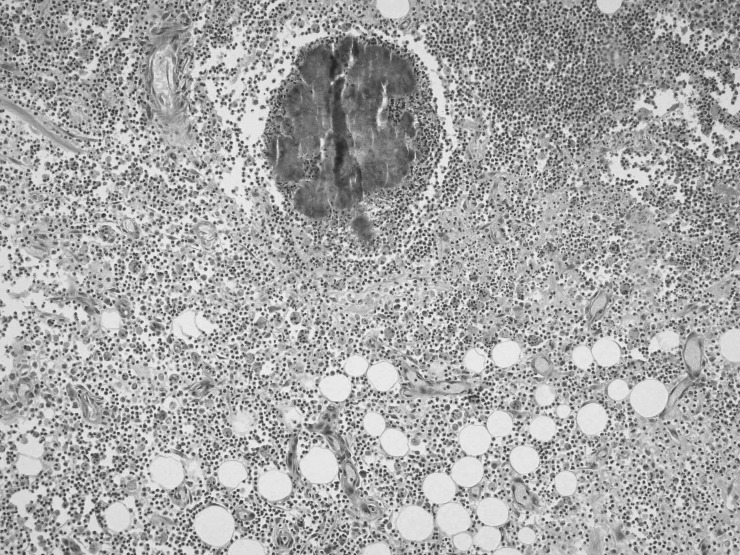

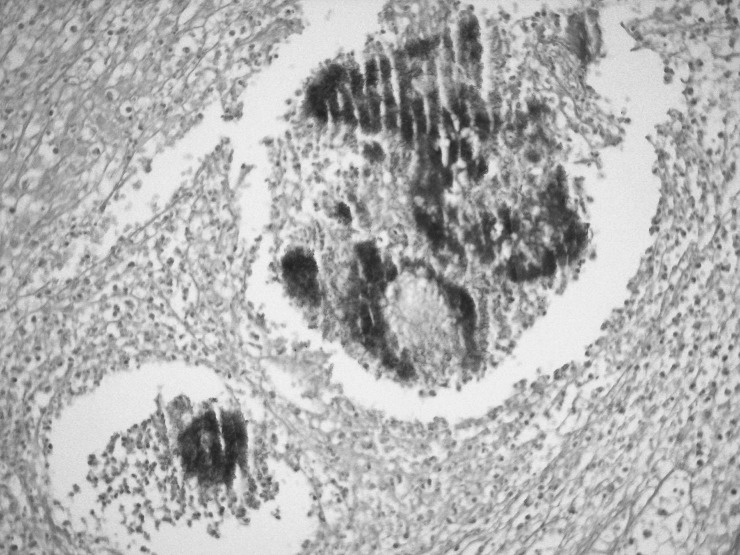

During exploratory laparotomy, a mass was identified that almost totally occupied the pelvic orifice. The mass impinged on the both ureters, especially the right ureter, and involved the sigmoid colon, uterus, both ovaries, and the appendix, and it had invaded the local structures. Therefore, several procedures were done including total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, appendectomy, low anterior resection, and Hartmann end colostomy. Histopathologic examination showed mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate (lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils) and microabscesses localized to the intestinal serosa near the ovary. Scattered Actinomyces colonies were detected in the foci of inflammatory cell infiltrate (Figs. 1 and 2). The bacterial colonies were histochemically positive on periodic acid Schiff staining (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Actinomyces colony within a microabcess near the ovarian stroma (left). H&E (×40).

Fig. 2.

Actinomyces colony intermingled with mixed inflammation in the fatty tissue of the intestinal serosa. H&E (×100).

Fig. 3.

Actinomyces bacterial colony. Periodic acid Schiff (×200).

The patient was placed on parenteral crystallized penicillin (6 million units given 4 times daily for 10 days), which was replaced by oral amoxicillin (1 g given 4 times daily for 6 months) when she was discharged from hospital. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) performed during the fourth postoperative month showed no pathology. The colostomy was closed with no complication after 6 months of medical therapy.

Discussion

Actinomycosis, first described by Ponfick in 1879, is a chronic suppurative disease caused by anaerobic, filamentous, gram-positive bacteria. Actinomyces israelii is part of the microflora of the human oral cavity, gastrointestinal tract, and genital tract. The organism cannot cross normal mucosal barriers. Therefore, opportunistic infections can occur only in the context of underlying local disease such as trauma, surgery, or a foreign body that penetrates the mucosal barrier.7

There are 3 main clinicopathologic presentations described, with varied incidence, including cervicofacial, thoracic, and abdominopelvic.7–10 Cervicofacial involvement is the most common, and abdominopelvic involvement is second or third in frequency after thoracic disease.4 Other sites of involvement also have been reported, including the liver, bone, and perianal region.6

The pathogenesis of abdominal actinomycosis is poorly understood. Intra-abdominal organ involvement may occur as a blood-borne infection or by swallowing. Actinomyces bacteria normally inhabit the colon, predominating in areas of stagnation such as the cecum and appendix. Actinomyces organisms require injury to the normal mucosa to penetrate and cause disease. Predisposing factors may include appendicitis, diverticulitis, gastrointestinal perforation, previous surgery, foreign body, or neoplasia. Therefore, abdominal actinomycosis is included in the differential diagnosis with other inflammatory diseases such as ulcerative colitis, Crohn disease, tuberculosis, diverticulitis, and pelvic inflammatory disease.7

Pelvic actinomycosis recently has become more prevalent. The pathogenesis of pelvic actinomycosis may occur as either an ascending infection from the lower genital tract or spread from an intestinal lesion.4 Recent reports have documented an increased incidence of pelvic actinomycosis in women using IUDs. The association between IUDs and pelvic actinomycosis was first described in 1970 and has been well documented.11 Actinomyces can be identified on routine vaginal examination in 10% asymptomatic IUD users, and 25% IUD users have associated symptoms. Although IUD use is strongly correlated with abdominopelvic actinomycosis, the duration of IUD implantation that increases the risk of developing actinomycosis infection has not been established.7 Although there are numerous contraceptive methods available worldwide, the IUD still is important. The most frequently used IUDs in Turkey (Multiload, MLCu 250/375; Nova T, TCu 200Ag/380Ag; and Pregna, TCu 380A) have different models and ratios of copper. New IUDs have been developed that have different hormonal activities. The different IUD models have specific advantages and disadvantages.

There are no specific signs or symptoms of abdominopelvic actinomycosis. Although the most common physical examination findings include a palpable mass, visible sinus tract, or fistula, the most common clinical presentation includes abdominopelvic pain, nausea, vomiting, fever, weight loss, and defecation disturbances, as in our patient.2,4,12 Most initial signs and symptoms become evident weeks or years after the primary lesion is evident. Typical findings from laboratory tests include anemia and increased white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and cancer antigens 125 and 19-9. Renal function deteriorates when abdominopelvic actinomycosis is complicated by severe hydronephrosis, and this may present with increased blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels.2 Hydronephrosis also has been reported as a consequence of ureteral obstruction by extensive pelvic involvement. In our experience, hydronephrosis resulting from ureteral obstruction may occur by 2 mechanisms: ureteral or urinary bladder impingement by a mass emerging from within the pelvic cavity, or ureteral fibrosis induced by a granulomatous reaction with retroperitoneal extension.11

Establishing a diagnosis of abdominopelvic actinomycosis preoperatively is difficult because of the nonspecific nature of clinical, laboratory, and radiographic findings.7,9 A preoperative diagnosis is made in <10% cases.9 In most cases, the diagnosis is made during the operation and confirmed by pathologic examination.4,13 The use of radiographic studies to establish a diagnosis of abdominopelvic actinomycosis has been extensively reported, but there are few specific radiographic signs. A CT scan may be helpful to establish the extent of the abdominal or pelvic organs involved and show features of the wall of the mass.12–14 In contrast, several reports have described that Actinomyces-associated masses are of intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and of intermediate to low signal intensity on T2-weighted sequences.15 Colonoscopic examination has been neglected in most previous reports because pathognomonic findings have not been noted in diseases originating predominantly from extramucosal lesions. Colonoscopy can be an indispensable diagnostic tool for excluding mucosal diseases, including colitis and neoplasms.12,16

A definitive diagnosis can be made based on histopathologic identification of actinomycotic structures. It is necessary to demonstrate microscopically either the pathogen itself or the specific yellow sulfur granule microcolonies formed by the actinomycotic filaments on tissue slides or smears from the fistula tract. Microbiologic cultures with a fresh sample rarely are positive because Actinomyces organisms require specific anaerobic conditions and require 1 week to exhibit growth. These cultures are negative in 76% cases.13 Some serologic assays have been developed, but the sensitivity and specificity of these assays are insufficient for use in clinical practice.4,6,9

Treatment of abdominal actinomycosis is dependent on both the extent of the disease and the condition of the patient. Most investigators have agreed that extensive lesions must be treated surgically with resection or drainage, supplemented with long-term antibiotic therapy. Penicillin G is the first-choice antibiotic therapy for actinomycosis. Initial treatment with parenteral penicillin G (10–24 million units daily) for 4 to 6 weeks can be followed by phenoxypenicillin, amoxicillin, or ampicillin for a minimum 6 to 12 months. Tetracyclines, doxycycline, erythromycin, clindamycin, or cephalosporins are suitable alternatives in patients who are allergic to penicillin.1,2,5,6,9,12,17,18 A few previous studies have suggested that antimicrobial therapy should be continued until all signs of inflammation disappear, which can take from several months to 1 year because of the reactive fibrosis caused by the organism.6 We share the same opinion about the duration of medical treatment. Combined medical and surgical treatment provides good results in >90% of patients, and mortality is rare.9

In conclusion, abdominopelvic actinomycosis is part of the differential diagnosis of abdominal malignancy, inflammatory conditions, and infectious disease. Women who have used IUDs are particularly at risk. A preoperative diagnosis is very rare because of nonspecific clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings. The difficulty of preoperative diagnosis may result in inappropriately extensive resections. However, optimal treatment includes abscess drainage and long-term high-dose penicillin to prevent recurrence.13

References

- 1.Tamer A., Gunduz Y., Karabay O., Mert A. Abdominal actinomycosis: a report of two cases. Acta Chir Belg. 2006;106(3):351–353. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2006.11679906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu P. K., Tsai C. A. Management of patients with huge pelvic actinomycosis complicated with hydronephrosis: a case report. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010;43(5):442–446. doi: 10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee I. J., Ha H. K., Park C. M., Kim J. K., Kim J. H., Kim T. K., et al. Abdominopelvic actinomycosis involving the gastrointestinal tract: CT features. Radiology. 2001;220(1):76–80. doi: 10.1148/radiology.220.1.r01jl1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tzeng Y. S., Chu P. W. Pelvic actinomycosis mimicking advanced colon cancer. J Med Sci. 2004;24(2):113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laish I., Benjaminov O., Morgenstern S., Greif F., Ben-Ari Z. Abdominal actinomycosis masquerading as colon cancer in a liver transplant recipient. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14(1):86–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang C. J., Huang T. J., Hsieh J. S. Pseudo-colonic carcinoma caused by abdominal actinomycosis: report of two cases. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2004;19(3):283–286. doi: 10.1007/s00384-003-0568-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi M. M., Baek J. H., Lee J. N., Park S., Lee W. S. Clinical features of abdominopelvic actinomycosis: report of twenty cases and literature review. Yonsei Med J. 2009;50(4):555–559. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2009.50.4.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norwood M. G., Bown M. J., Furness P. N., Berry D. P. Actinomycosis of the sigmoid colon: an unusual cause of large bowel perforation. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74(9):816–818. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.03156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari T. C., Couto C. A., Murta-Oliveira C., Conceição S. A., Silva R. G. Actinomycosis of the colon: a rare form of presentation. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000;35(1):108–109. doi: 10.1080/003655200750024623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu H. H., Tsan Y. T., Hu S. Y., Lin T. C., Hu W. H., Wang L. M. Bilateral hydronephrosis and hydroureters as first manifestations of abdominal actinomycosis: a case report. J Emerg Crit Care Med. 2009;20(2):92–97. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yagmurdur M. C., Akbulut S., Colak A., Aygun C., Haberal M. Retroperitoneal fibrosis and obstructive uropathy due to actinomycosis: case report of a treatment approach. Int Surg. 2009;94(4):283–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yegüez J. F., Martinez S. A., Sands L. R., Hellinger M. D. Pelvic actinomycosis presenting as malignant large bowel obstruction: a case report and a review of the literature. Am Surg. 2000;66(1):85–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitot D., De Moor V., Demetter P., Place S., Gelin M., El Nakadi I. Actinomycotic abscess of the anterior abdominal wall: a case report and literature review. Acta Chir Belg. 2008;108(4):471–473. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2008.11680268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soria-Aledo V., Flores-Pastor B., Carrasco-Prats M., Candel-Arenas M. F., Pellicer-Franco E., Garcia-Santos J. M., et al. Abdominopelvic actinomycosis: a serious complication in intrauterine device users. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83(9):863–865. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.0148a.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nozawa H., Yamada Y., Muto Y., Arita S., Aisaka K. Pelvic actinomycosis presenting with a large abscess and bowel stenosis with marked response to conservative treatment: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2007;1:141. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-1-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J. C., Ahn B. Y., Kim H. C., Yu C. S., Kang G. H., Ha H. K., et al. Efficiency of combined colonoscopy and computed tomography for diagnosis of colonic actinomycosis: a retrospective evaluation of eight consecutive patients. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2000;15(4):236–242. doi: 10.1007/s003840000232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lunca S., Bouras G., Romedea N. S., Pertea M. Abdominal wall actinomycosis associated with prolonged use of an intrauterine device: a case report and review of the literature. Int Surg. 2005;90(4):236–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diaz-Oller J., Tutosaus-Gomez J. D., Medina-Dominguez T., Arcos-Navarro A., Barranco-Garcia J. D., Alia-Diaz J. J., et al. Mesenteric actinomycosis with retroperitoneal involvement. Int Surg. 2001;86(1):57–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]