Abstract

One of the serious complications during a routine endodontic procedure is accidental ingestion/aspiration of the endodontic instruments, which can happen when proper isolation is not done. There are at present no clear guidelines whether foreign body ingestion in the gastrointestinal tract should be managed conservatively, endoscopically or surgically. A 5 year old boy reported to the Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry, D.A. Pandu Memorial R.V. Dental College, Bangalore, India, with a complaint of pain and swelling in the lower right back teeth region. Endodontic therapy was planned for the affected tooth. During the course of treatment the child accidentally swallowed a 21 mm 15 size K file. Endoscopy was performed immediately but the instrument could not be retrieved. The instrument passed out uneventfully along with the stools 48 h after ingestion.

Careful evaluation of the patient immediately after the accident helps in managing the patient effectively along with following the recommended guidelines.

Keywords: Foreign body, Canal, Instrument, Swallowing, Rubber dam, Isolation, K-file, Endoscopy, Accidental ingestion, Endodontic procedure, Dental materials, Aspiration, Caries, Dental care for disabled children, Radiography, Dental prostheses, Dental restoration, Emergencies, Endodontic files, Endodontics, Dental instruments, Foreign bodies

1. Introduction

Accidental foreign body ingestion is a common clinical problem especially in children. Although complications are higher with sharp implements, reported rates of gastrointestinal perforation still remain rare at less than 1%. Dentures and small orthodontic appliances (73%) account for the majority of accidental sharp objects ingestion in normal adults. Other commonly ingested sharp objects also include sewing needles, tooth picks, chicken and fish bones, straightened paper clips and razor blades. Most foreign bodies pass through the gastrointestinal tract uneventfully. The majority of the reported literature describe the management of ingested blunt objects. However, ingestion of sharp objects can still occur with a higher rate of perforation corresponding to treatment dilemmas (Dhandapani et al., 2009).

There are at present no clear guidelines whether foreign body ingestion in the gastrointestinal tract should be managed conservatively, endoscopically or surgically (Kürkciyan et al., 1996).

An important point to note here is that endoscopic or surgical intervention is indicated if significant symptoms develop or if the object fails to progress through the gastrointestinal tract (Uyemura, 2006a).

1.1. Systematic review of literature

1.1.1. Incidence

Foreign body ingestion is a commonly seen accident in emergencies, usually in children (80%), elderly, mentally impaired, or alcoholic individuals, whereas it may occur intentionally in prisoners or psychiatric patients (Pavlidis et al., 2008).

Fixed prosthodontic therapy had the highest number of incidents of adverse outcomes. Ingestion was a more prevalent outcome than aspiration. Dental procedures involving single-tooth cast or prefabricated restorations involving cementation have a higher likelihood of aspiration (Kürkciyan et al., 1996).

For the endodontic instruments: the incidence of aspiration was 0.001 per 100,000 root canal treatments and the incidence of ingestion was 0.12 per 100,000 root canal treatments. The aspirated endodontic instruments and dental items required statistically more frequent hospitalization than the ingested items (P < 0.0001). The endodontic instruments did not require more frequent hospitalization than other dental items when aspirated (ns) and when ingested (ns). No fatal outcome was reported (Susini et al., 2007).

Neuhauser suggested that patients in a supine position are more or less prevented from swallowing foreign objects (Neuhauser, 1997).

Barkmeier et al. stated that supine position increases the risk of swallowing (Barkmeier et al., 1978).

The percentage of endodontic instruments aspirated or ingested were 2.2% and 18%, respectively. For the endodontic instruments, the prevalence for aspiration was 0.0009 per 100,000 root canal treatments and the prevalence for ingestion was 0.08 per 100,000 root canal treatments. All aspiration cases (100%) required hospitalization compared to 36% for ingestion (Susini and Camps, 2007) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of endodontic instruments or dental items involved and the percentage of occurrence of either aspiration or ingestion (Susini and Camps, 2007).

| Aspiration | Ingestion | |

|---|---|---|

| Endodontic file | 1 | 57 |

| Barbed broach | – | 27 |

| Bur | – | 125 |

| Temporary crown | 5 | 15 |

| Prosthesis | 27 | 136 |

| Matrix band | – | 14 |

| Piece of amalgam | 2 | 17 |

| Screw post | 3 | 9 |

| Extracted tooth | – | 7 |

| Orthodontic bracket | – | 8 |

| Inlay core | 7 | 49 |

| Total | 44 | 464 |

1.1.2. Complications

Complications usually occur with sharp, thin, stiff, pointed and long objects.

Dental procedures involving single-tooth cast or prefabricated restorations involving cementation have a higher likelihood of aspiration (Tiwana et al., 2004).

The risk of complications is increased with long sharp metal objects and animal bones, and may be higher in patients with adhesions due to prior abdominal surgery. Pre-existing intestinal disease such as Crohn’s or intestinal stenosis may predispose to complications. The use of overtubes has made endoscopic removal of sharp objects safer. In patients at increased risk for complications, it is recommended to employ early endoscopic retrieval of ingested foreign objects (Henderson et al., 1987).

Other complications and sequelae include post-obstructive pneurnonitis, pulmonary abscess, and bronchiectasis (E1Badrawy, 1985).

1.1.3. Management

Early location of an inhaled or ingested foreign body facilitates appropriate and timely treatment management and referral. When a foreign body passes into the gastrointestinal tract, clinical symptoms and signs should be monitored closely until it is excreted or removed. An endodontic file can pass through the gastrointestinal tract asymptomatically and apparently atraumatically within 3 days (Kuo and Chen, 2008).

The majority of these dental instruments are radiopaque. An immediate attempt should be made to remove a risky object by gastroscopy after the initial radiograph has been taken. If this fails, clinical follow-up with serial abdominal radiographs should be obtained. If the anatomical position of the object appears not to change and, most commonly, remains in the right lower abdominal quadrant, an attempt at colonoscopic removal is indicated (where a long, flexible, lighted tube called a colonoscope, or scope, is inserted into the anus and slowly guides it through the rectum and into the colon). If this is unsuccessful, laparoscopic exploration with fluoroscopic guidance should be carried out to localize and remove the objects either by ileotomy, colotomy, or by appendectomy (Klingler et al., 1998).

Noninvasive procedures for managing airway obstruction include back blows in infants, the Heimlich maneuver, abdominal or chest thrusts in pregnant or obese patients, and finger sweeps when the object is located in the oral cavity in unconscious adults (Hoekelman et al., 1992).

Foreign bodies lodged in the esophagus should be removed endoscopically, but some small, blunt objects may be pulled out using a Foley catheter (The technique for Foley catheter extraction of an esophageal foreign body is fairly simple. With the patient in a sitting position, a Foley catheter, is passed orally. The patient is then placed in a prone lateral Trendelenburg position to reduce the risk of tracheal or nasopharyngeal obstruction during foreign body removal. The balloon is filled with a water-soluble contrast medium, and the catheter is withdrawn with steady, slow traction, making certain there is no hesitation when the hypopharynx is encountered. When the foreign body reaches the pharynx, it may be retrieved with forceps or expelled with a forceful cough. If the first pass of the catheter is unsuccessful, the procedure may be repeated once, but multiple attempts are not recommended.) or pushed into the stomach using bougienage. Once they are past the esophagus, large or sharp foreign bodies should be removed if reachable by endoscope. Small, smooth objects and all objects that have passed the duodenal sweep should be managed conservatively by radiographic surveillance and inspection of stool. Endoscopic or surgical intervention is indicated if significant symptoms develop or if the object fails to progress through the gastrointestinal tract (Uyemura, 2006b).

The first order of business is ensuring that the airway is not compromised and explaining the patient of the problem. Immediate referral (with escort) to a medical facility for appropriate radiographs and determination of required medical action is mandatory, regardless of how well the patient looks. According to the literature, all aspirated foreign objects and approximately one-third of ingested items require the patient to be hospitalized. Proper documentation also is important to reduce liability in the event of litigation (Hill and Rubel, 2008).

Measures used to prevent aspiration during dental care include: using a rubber dam during all restorative and endodontic procedures; using floss ligature on objects such as rubber dam clamps, cast crowns and bridges, elastic separators and space maintainer appliances; and using a gauze net barrier to protect the airway during extractions and other procedures in which rubber dam and ligatures are not appropriate (Wandera et al., 1993).

Because many patients who have swallowed foreign bodies are asymptomatic, physicians must maintain a high index of suspicion. The majority of ingested foreign bodies pass spontaneously, but serious complications, such as bowel perforation and obstruction, can occur. Foreign bodies lodged in the esophagus should be removed endoscopically, but some small, blunt objects may be pulled out using a Foley catheter or pushed into the stomach using bougienage [corrected] Once they are past the esophagus, large or sharp foreign bodies should be removed if reachable by endoscope. Small, smooth objects and all objects that have passed the duodenal sweep should be managed conservatively by radiographic surveillance and inspection of stool.

2. Case report

2.1. Day 1

A 5 year old boy reported to the Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry, D.A. Pandu Memorial R.V. Dental College, Bangalore, India, with the chief complaint of pain and swelling in the lower right back tooth (Numbers 84, 85) region since 3 days.

Pulp Therapy was planned. Rubber dam isolation was not possible (owing to considerable loss of tooth structure & presence I/O swelling). Endodontic K-files of 21 mm length (6 Nos.) were inserted into 84, 85 (3 in each). When the files were inserted, the child had a bout of cough prompting the operator to try to retrieve the instrument. Parents help was sought immediately as he was in attendance. Parent’s hand insertion into the mouth spontaneously and the patient’s uncontrolled movement resulted in accidental passage of the instrument into the mouth. The operator tried unsuccessfully to retrieve the instrument by making the patient spit and by patting the child on the back.

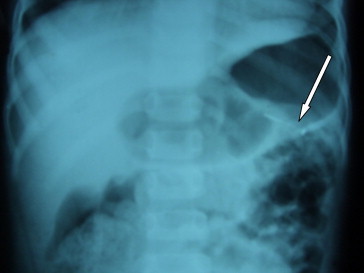

The patient was rushed to the college hospital immediately. The case was attended to by a Pediatrician and General surgeon. Chest X-ray was taken (Fig. 1). On the surgeons’ advice a endoscopy was planned. Since the gastroenterologist was not available, the child was admitted in the hospital. The child passed motion by around 11.30 am. Parent did not examine the stools.

Figure 1.

X-ray I (taken immediately after the ingestion).

Endoscopy was performed at 3.30 pm and a repeat endoscopy at 7.30 pm, but the instrument could not be located during both the attempts. Surgical gastroenterologist suggested a possible scenario of the instrument having perforated the intestinal mucosa and gone into other tissue planes. So a CT scan was planned the following day and a surgical opinion sought. The patient slept uneventfully.

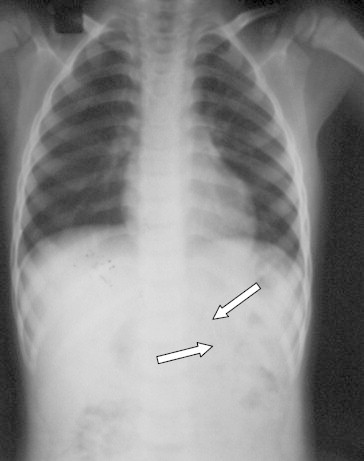

2.2. Day 2

A repeat X-ray was taken (Fig. 2) and both the X-rays were examined by a General surgeon after assessing the child and suggested that the child can start taking regular food. The child was given medication to improve gastric motility and was advised to be kept under observation for the following 48 h. Patient passed motion at 10 pm but the instrument was not found. The child remained asymptomatic.

Figure 2.

X-ray (taken on day 2) showing the instrument having descended further down.

2.3. Day 3

In the morning the child passed stools from which the unbroken instrument was finally retrieved. A confirmatory lower abdomen X-ray (Fig. 3) was taken and was found to be normal.

Figure 3.

Post operative radiograph.

2.4. Suggested recommendations

-

(1)

Early location of an aspirated or ingested foreign body facilitates appropriate and timely treatment management and referral (Kuo and Chen, 2008).

-

(2)

Whenever a foreign body passes into the gastrointestinal tract, clinical symptoms and signs should be monitored closely until it is excreted or removed. Clinical follow-ups with serial abdominal radiographs should be obtained (Kuo and Chen, 2008; Klingler et al., 1998).

-

(3)

Noninvasive procedures for managing airway obstruction include back blows in infants, the Heimlich maneuver, abdominal or chest thrusts in pregnant or obese patients, and finger sweeps when the object is located in the oral cavity (Hoekelman et al., 1992).

-

(4)

Foreign bodies lodged in the esophagus should be removed endoscopically, but some small, blunt objects may be pulled out using a Foley catheter or pushed into the stomach using bougienage (Uyemura, 2006b).

-

(5)

Once they are past the esophagus, large or sharp foreign bodies should be removed if reachable by endoscope (Uyemura, 2006b).

-

(6)

Conservative management should include radiographic surveillance and periodic stool inspection (Uyemura, 2006b).

-

(7)

Endoscopic or surgical intervention is indicated if significant symptoms develop or if the object fails to progress through the gastrointestinal tract (Uyemura, 2006a).

-

(8)

Thorough Isolation (Like Rubber Dam Application) should be done during any Endodontic Procedure.

-

(9)

Signs and symptoms of a child becoming uncooperative should be observed and necessary modification to be performed.

-

(10)

A post operative radiograph should be taken to confirm that the ingested instrument has been excreted or removed (Uyemura, 2006a).

Ethical clearance

As this article is a review article, there is no need to get an ethical clearance.

References

- Barkmeier W.W., Cooley R.L., Abrams H. Prevention of swallowing or aspiration of foreign objects. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1978:97. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1978.0316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhandapani Ramyia G., Kumar Susim, O’Donnell Mark E., McNaboe Ted, Cranley Brian, Blake Geoff. Cases J. 2009;2:117. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-117. Dental root canal treatment complicated by foreign body ingestion: a case report. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1Badrawy H.E. Aspiration of foreign bodies during dental procedures. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 1985;51:145–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C.T., Engel J., Schlesinger P. Foreign body ingestion: review and suggested guidelines for management. Endoscopy. 1987;19(2):68–71. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1018238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill E.E., Rubel B. A practical review of prevention and management of ingested/aspirated dental items. Gen Dent. 2008;56(7):691–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoekelman R.A., Friedman S.B., Nelson N.M., Seidel H.M. 2nd ed. CVMosbYear Book; St. Louis: 1992. Primary Pediatric Care. pp 263–263, 1249–1251. [Google Scholar]

- Klingler Paul, Seelig Matthias, DeVault Kenneth, Wetscher Gerold, Floch Neil, Branton Susan, Hinder Ronald. Ingested Foreign Bodies within the Appendix: A 100-Year Review of the Literature. Dig. Dis. 1998;16:308–314. doi: 10.1159/000016880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo S.-C., Chen Y.-L. Accidental swallowing of an endodontic file. Int. Endod. J. 2008;41(7):617–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2008.01392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kürkciyan I., Frossard M., Kettenbach J., Meron G., Sterz F., Röggla M., Laggner A.N., Department of Emergency Medicine, General Hospital of Vienna, University of Vienna, Austria Z. Gastroenterol. 1996;34(3):173–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhauser W. Swallowing of a temporary bridge by a reclining patient being treated by a seated dentist. Quintessence Int. Dent. Dig. 1997;6:9–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlidis T.E., Marakis G.N., Triantafyllou A., Psarras K., Kontoulis T.M., Sakantamis A.K. Management of ingested foreign bodies: how justifiable is a waiting policy? Surg. Laparosc. Endosc. Percutan. Tech. 2008;18(3):286–287. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31816b78f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susini G., Camps J. Accidental ingestion and aspiration of root canal instruments and other dental items in a French population. European Cells and Materials. 2007;13(Suppl. 1):34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01249.x. ISSN 1473-2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susini G., Pommel L., Camps J. Accidental ingestion and aspiration of root canal instruments and other dental foreign bodies in a French population. Int. Endod. J. 2007;40(8):585–589. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2591.2007.01249.x. Epub 2007 May 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwana Karen K., Morton T., Tiwana P.S. Aspiration and ingestion in dental practice: a 10-year institutional review. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2004;135(9):1287–1291. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyemura M.C. Wray; Colorado, USA: 2006. Wray Rural Training Tract Family Medicine Residency Program. Foreign body ingestion in children. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Apr 15;73(8):1332. [Google Scholar]

- Uyemura M.C. Foreign body ingestion in children. Am. Fam. Physician. 2006;73(8):1332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandera Angela, John M.S., Conry P. Aspiration and ingestion of a foreign body during dental examination by a patient with spastic quadriparesis: case report. Pediatr. Dent. 1993;15(5) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]