Abstract

Infection with influenza virus induces severe pulmonary immune pathology that leads to substantial human mortality. While antiviral therapy is effective in preventing infection, no current therapy can prevent or treat influenza-induced lung injury. Previously, we reported that influenza-induced pulmonary immune pathology is mediated by inflammatory monocytes trafficking to virus-infected lungs via CCR2, and that influenza-induced morbidity and mortality are reduced in CCR2-deficient mice. Here, we evaluated the effect of pharmacologically blocking CCR2 with a small molecule inhibitor (PF-04178903) on the entry of monocytes into lungs and subsequent morbidity and mortality in influenza-infected mice. Subcutaneous injection of mice with PF-04178903 was initiated one day prior to infection with influenza strain PR8. Compared to vehicle controls, PF-04178903-treated mice demonstrated a marked reduction in mortality (75% vs. 0%), and had significant reductions in weight loss and hypothermia during subsequent influenza infection. Drug-treated mice also displayed significant reductions in bronchial alveolar lavage fluid (BALF) total protein, albumin, and lactose dehydrogenase (LDH) activity. Administration of PF-04178903 did not alter viral titers, severity of secondary bacteria infections (S. pneumonae), or levels of anti-influenza neutralizing Abs. Drug-treated mice displayed an increase in influenza nucleoprotein-specific cytotoxic T cell activity. Our results suggest that CCR2 antagonists may represent an effective prophylaxis against influenza-induced pulmonary immune pathology.

Introduction

High mortality among humans infected with highly pathogenic influenza viruses, including the 1918 pandemic virus and H5N1 avian flu virus, is caused by the propensity of these viruses to induce high levels of proinflammatory cytokines, and the consequent severe immune pathology (1, 2). Such infections are characterized by toxemia, hypoxemia, and severe hemorrhagic inflammatory edema of the lungs (3). Autopsies of H5N1 victims show alveolar damage with the infiltration of macrophages, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, and hemophagocytic syndrome, a disorder characterized by excessive activation of mononuclear phagocytosis, which is thought to be cytokine-driven (4-6). Currently marketed antiviral neuraminidase (NA) inhibitors are able to control viral infections if given early to patients (7, 8), but there is no therapy available to reduce the hypercytokinemia and immune pathology induced by highly pathogenic influenza viruses. The clinical use of corticosteroids in H5N1-infected patients has been tested, but disease outcome has not been improved with this treatment (7).

The accumulation of monocytes and macrophages during infections is typically beneficial, especially during bacterial infections (9, 10), and increasing the number of these cells can reduce the severity of bacterial pneumonia (11). However, monocyte/macrophage accumulation has also been associated with the development of lung injury in several inflammatory pulmonary diseases (12-14). In the case of influenza, monocyte accumulation appears to be primarily pathological, as CCR2 deficient mice display reduced influenza-induced pneumonitis (15). We have recently shown that influenza-induced pulmonary immune pathology is caused by specific cells derived from inflammatory monocytes, which enter lungs using the chemokine receptor CCR2 (16). CCR2-deficient mice display markedly decreased influenza-induced morbidity and mortality (16). Inflammatory monocytes that enter lungs in response to influenza infection initially differentiate into CD11cintMHCIIint transitional cells, then mature into either CD11b+ dendritic cells or exudate macrophages (16). These monocyte-derived cells produce high levels of TNF-α and nitric oxide (NO), which meditate tissue damage but contribute very little to viral clearance (17-19). A subsequent study suggested that TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) expressed on mononuclear phagocytes induces epithelial cell apoptosis and immune pathology (20). The data derived from CCR2-deficient mice suggest that blocking the entry of inflammatory monocytes into lungs by CCR2 antagonism may reduce morbidity and mortality caused by highly pathogenic influenza infections. However, effects seen in knockout mice may not guarantee the efficacy of CCR2 antagonist treatment during influenza infections because the knockout mice may have abnormal compensatory effects in other aspects of biology. Hence, pharmacological vs. genetic manipulation of CCR2 activity remained to be evaluated directly in vivo.

Monocyte-derived cells play important roles not only in innate responses to pathogens, but also in the polarization and expansion of lymphocytes (21). This raises concerns that CCR2 inhibition may result in decreased immune responses to influenza infection. Published studies disagree as to whether CCR2-deficient mice have increased viral titers after influenza infection (11, 20). These mice are also more susceptible to some bacterial infections (9, 10). Therefore, influenza viral titers and bacterial load in the lungs after secondary bacteria infections were examined here to assess possible side effects caused by CCR2 inhibitor treatment. Viral neutralizing Abs and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses were also assessed, as they comprise two of the most effective arms of immunity against influenza virus (2).

Here we administered a small molecule CCR2 inhibitor (PF-04178903) in an attempt to modulate lung injury during influenza infection in a murine model. We used the H1N1A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (PR8) strain to mimic the lung injury seen during highly pathogenic flu infection. This strain causes high mortality in mice, induces severe immune pathology, and localizes to the lungs. We found that PF-04178903-treated mice had reduced pathology, morbidity, and mortality during influenza infection when the drug was administered prior to infection, and that this prophylaxis did not impact immune responses against influenza virus or secondary bacterial infections.

Materials and Methods

Mice, drug treatment, and influenza infection

C57BL/6 mice and CD45.1 mice were purchased from Charles River (Wilmington, MA) or The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). All mice used in these experiments were 10 to 14 weeks old females. The CCR2 antagonist utilized for these studies (1,5-anhydro-2,3-dideoxy-3-{[(1R,3S)-3-isopropyl-3-({4-[4-(trifluoromethyl)pyridin-2-yl]piperazin-1-yl}carbonyl)cyclopentyl]amino}-4-O-methylpentitol) was provided by Pfizer and is designated PF-04178903. This compound exhibits nanomolar potency in ligand competition binding or in vitro chemotaxis assays against murine CCR2, with approximately 10-fold less potency observed for murine CCR5 in comparable assays. Prior to use, compound was dissolved in PBS at 8.3 mg/ml and injected s.c. twice daily at a dose of 50 mg/Kg. For influenza infection, mice were anesthetized one day following initiation of compound dosing with ketamine (100mg/kg) / xylazine (10mg/kg) i.p. and then infected with H1N1 influenza virus strain A/Puerto Rico/8/34 (PR8) (ATCC, Manassas, VA, VR-95) intranasally. For flow cytometric analysis, mortality, lung injury and viral titer studies, mice were infected with a high viral dose: 30 μl of 5 × 107 TCID50/ml. For studies of secondary bacteria pneumonia, serum antibody titers, and in vivo CTL assays, mice were infected with low dose: 30 μl of 1.6 × 107 TCID50/ml. Body weights and rectal temperatures of infected mice were monitored daily. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at Duke University.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and lung parenchyma cell isolation

BAL cells were collected as described previously (22). Tracheas of euthanized mice were cannulated with an 18 gauge angiocath connected to a 1 ml syringe and the lungs flushed with 0.6∼0.8 ml PBS 5 times. BAL cells were washed once with HBSS. To obtain lung parenchymal cells, lungs were perfused with 3 ml HBSS-collagenase (1 mg/ml), incubated in 5 ml HBSS-collagenase (1mg/ml) and DNase (1μg/ml) at 37°C for 40 min, minced, dissociated through a 70um mesh strainer, and centrifuged at 450g at RT for 20 min over a 18% Nycodenz (Accurate Chemical and Scientific, Westbury, New York) cushion. Low-density cells were collected, washed in PBS with 1% BSA and 10mM EDTA, and subjected to Ab staining.

Flow cytometric analysis

Abs used included anti-IA/IE-FITC, anti-Ly6G-PE, and anti-Gr-1-APC (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA); anti-CD11b-APC/Cy7, anti-CD11c-PECy5.5 (eBioscience, San Diego, CA). Cells were stained in PBS containing 10 mM EDTA, 10 mM Hepes, 1% BSA, 5% normal mouse serum, 5% normal rat serum, and 1% Fc block (eBioscience) at 4°C for 30 min, washed 3 times, then analyzed using a BD LSRII™ flow cytometer.

Total BAL protein, albumin concentration, and LDH activity

Influenza-infected mice were treated with PF-04178903 starting at day -1, and sacrificed on day 5, 7, or 9, along with PBS-injected control mice. Three ml of BAL fluid was obtained as described above and cells were removed by centrifugation. Protein concentrations in the supernatant fluid were determined via Bradford™ assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL) according to manufacturer's instructions. Albumin concentrations in BAL fluid were measured using a mouse albumin ELISA kit (Immunology Consultants Laboratory, Newberg, OR). Lactate dehydrogenase activities in BAL fluid were measured using an LDH based toxicology assay kit (Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Viral titer measurements

Lungs from control or influenza-infected mice at selected times post infection were perfused with PBS and homogenized by rubbing lung tissues between frosted microscope slides (Fisher Scientific). Influenza viral titers in lung homogenates were quantified by viral plaque assay (16). Briefly, lung homogenates were serially diluted in PBS containing Ca++ and Mg++ and 0.1% BSA, plated on confluent monolayers of MDCK cells, and allowed to adsorb for 1 hour at 37°C in a tissue culture incubator. Inocula were then removed and the monolayer was overlayed with 1× MEM containing agar and TPCK trypsin (Sigma) at a final concentration of 0.1μg/ml. Plates were incubated two days in a tissue culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO2) to allow plaques to form. When plaques were clearly visible, agar was removed and the plates were stained with 1% crystal violet in methanol to aid in enumeration of PFUs.

Secondary bacterial pneumonia infection assays

Type 3 S. pneumoniae (ATCC 6303) was rehydrated and grown in Bacto™ Todd-Hewitt broth (BD bioscience) overnight at 37°C. One ml of overnight culture was diluted 1:10 in fresh media and incubated 6 hours at 37°C to attain log phase. On day 5 following infection (day 6 after initiation of PF-04178903 treatment), mice were anesthetized by i.p. injection of ketamine and xylazine and inoculated with 104 CFU (colony forming units) of S. pneumoniae intranasally. Two days after S. pneumoniae inoculation (day 7), mice were euthanized and their lungs were harvested and homogenized as described above for viral PFU assays. Lung homogenates were serially diluted 1:10 and plated on Columbia agar with 5% sheep blood (BD Bioscience) to determine lung bacteria CFU.

Serum viral neutralizing Ab titers

Mice were treated with PF-04178903 starting on day -1, and infected with influenza on day 0. Serum samples were collected on days 21 and 28, heat-inactivated, serially-diluted ten-fold in MEME containing 5% FBS into 96-well plates, and incubated with influenza virus (10 TCID50/μl) for 1 hour at 37°C. MDCK cells (104) were added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37°C. Culture media was changed 48h later to MEME with 2% BSA and incubated an additional 72 hours. Next, 0.5% chicken red blood cells (CRBC) were added to all wells. Plates were incubated at 4°C for one hour, and observed for agglutination. The serum viral neutralizing titer is defined as the reciprocal of the highest dilution of serum where wells show no agglutination of CRBCs.

In vivo CTL assays

CTL assays were performed as previously described (23) with some modifications. Briefly, target cells were prepared by lysing RBCs from naive CD45.1 splenocytes. The remaining cells were then washed and split into two populations. One population was pulsed with 2 × 10-6 M influenza nucleoprotein peptide (366∼374) (AnaSpec, San Jose, CA), incubated at 37°C for 45 min, and labeled with 4 μM CFSE (CFSEhigh cells). The second control target population was pulsed with control OVA peptide and was labeled with 0.4 μM CFSE (CFSElow cells). For i.v. injection, 4 × 106 cells from each population were mixed together in 200 μl of PBS and injected into recipient C57BL/6 mice that had been infected with influenza PR8 virus 9 days earlier, and treated with PF-04178903 or vehicle. Six hours later, recipient mice were sacrificed, and mediastinal lymph nodes and spleens were harvested. Cell suspensions were analyzed by flow cytometry and each target population identified by their specific CFSE fluorescence intensity. Up to 4000 CD45.1+CFSE+ cells were collected for analysis. To calculate specific lysis, the following formula was used: percentage specific lysis = [1 - (ratio NP-primed/ratio OVA-primed) × 100].

Statistics

All numerical data are presented as mean ± SD. The comparison between survival curves was performed by logrank test in Graph Pad Prism® software (San Diego, CA). This test is equivalent to the Mantel-Haenszel test. All the other data were analyzed by ANOVA or unpaired student t test using Prism® software as indicated in the figure legends.

Results

Inhibition of influenza-induced cell accumulation in the lungs of mice by PF-04178903

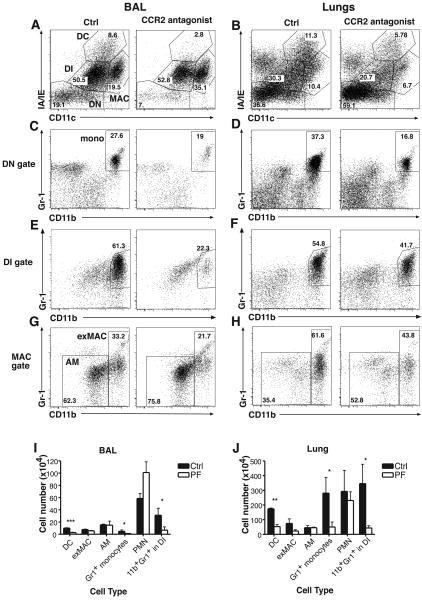

The decrease in lung inflammation and mortality seen in CCR2-deficient mice during influenza infection (16, 20) motivated us to investigate whether the murine reactive small molecule CCR2 antagonist PF-04178903 could reduce monocytic cell infiltration into influenza-infected lungs, and ultimately decrease the mortality in infected mice. To test the effect of the drug on reducing monocytic cell infiltration, mice were infected with PR8 (H1N1) and then injected with PF-04178903 starting on day 0. On day 5, lungs of infected mice were harvested and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. The cell populations in BAL and lung digests were gated as in our previous publication (16) and shown in Figure 1A-H. The forward and sideward scatter characteristics of the various cell populations are shown in supplementary figure 1.

Figure 1.

Monocytes, dendritic cells, and CD11b+Gr-1+ DI cells are decreased in the lungs of PF-04178903-treated mice during influenza infection. Mice were treated with PF-04178903 or PBS starting immediately after virus inoculation. On day 5 of influenza infection, mice were sacrificed. Cells from BAL (A, C, E, G) and lung digests (B, D, F, H) were harvested from PF-04178903-treated and PBS-treated mice and analyzed by flow cytometry. Gate labels: DC, dendritic cells; DN, double negative (CD11c- MHCII-) cells; DI, double intermediate (CD11cintMHCIIint); MAC, total macrophages; AM, alveolar macrophages; exMAC, exudate macrophages; mono: Gr-1+ monocytes. Results shown are from individual mice representative of two separate experiments. Numbers shown represent the percentage of cells within the gates. (I&J) Total cell numbers (per mouse) of individual cell types obtained from BAL (I) or lung digests (J) of PF-04178903-treated and PBS-treated mice were calculated. Bars represent the mean ± SD for 3 mice per group. *, p < 0.05; **, p<0.005; ***, p<0.0005 by student's t test.

As anticipated, PF-04178903-treated mice exhibit a marked reduction in the percentage of inflammatory (Gr-1+) monocytes present in both BAL and lung parenchyma (Fig. 1C&D). This is mirrored by a similar reduction in CD11b+Gr-1+CD11cintMHCIIint double-intermediate (DI) cells (Fig. 1E&F ), CD11c+MHCIIhi dendritic cells (DC) (Fig. 1A&B), and CD11chiMHCIIloCD11b+ exudate macrophages (ExMACs) (Fig. 1A, B, G, &H). The CD11b+Gr-1+cells in the DI gate are transitional cells that arise as inflammatory monocytes develop into DC or macrophages and increase expression of CD11c and MHCII (16). In BAL fluid, PF-04178903 reduced by 75% the numbers of Gr1+ monocytes, DC, and CD11b+Gr-1+ DI cells (Fig. 1I). In lungs, DC numbers were reduced 70%, and the numbers of Gr1+ monocytes and CD11b+Gr-1+ DI cells were reduced 80% in compound-treated mice (Fig. 1J). As expected, the number of neutrophils (PMN, CD11b+CD11cloLy6G+, Suppl. Fig. 1) and alveolar macrophages (AM, CD11c+MHCIIloCD11blo, Fig. 1A&G) were not significantly different between control and PF-04178903-treated mice (Fig. 1I&J). There was an observed trend toward reduction in the number of exMACs in the lungs after PF-04178903 treatment (70%), but it did not reach statistical significance. The extent of reduction in the numbers of monocytes and monocyte-derived cells in PF-04178903-treated lungs (70%∼80%) is slightly lower than was seen in CCR2-deficient lungs (80∼85%) (16). We also examined inflammatory cell populations in the lungs of mice treated with PF-04178903 beginning one day prior to influenza infection (day -1). We found no significant differences on day 3 between lung cell populations in mice treated on day -1 and mice treated on day 0 with PF-04178903 (data not shown).

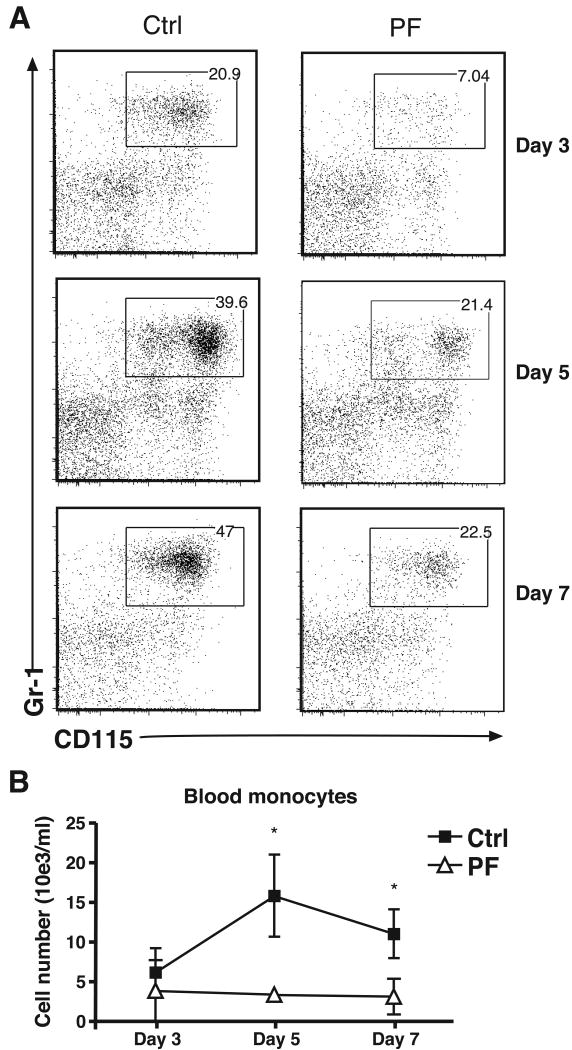

CCR2 is required both for the migration of inflammatory monocytes from the bone marrow into the blood and for the extravasation of these cells from the blood into tissues (24). In mice treated with PF-04178903 starting on day -1, the number of blood monocytes did not display the increase that typically occurs during influenza infection (Fig. 2). This finding suggests that the reduced accumulation of monocytes and monocyte-derived cells seen in the lungs of PF-04178903 treated mice is due, at least in part, to a reduction in inflammatory monocyte mobilization from the bone marrow.

Figure 2.

The number of inflammatory monocytes in the blood of control or PF-treated mice after influenza infection. Mice were treated with PF-04178903 (PF) or PBS (Ctrl) starting one day before influenza virus inoculation. On days 3, day 5, and day 7 of influenza infection, mice were sacrificed and their blood collected and subjected to flow cytometric analysis. (A) The profile of CD115 vs. Gr-1 staining of blood CD11b+Ly6G- cells is shown. (B) Total cell number of blood inflammatory monocytes in PF-treated and Ctrl mice. Data is representative of two independent experiments. Bars represent mean ± SD for 4 mice per group. *, p < 0.05 by student's t test.

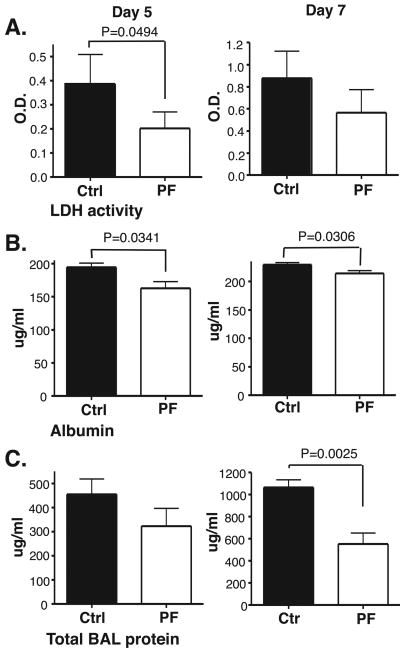

Inhibition of influenza-induced lung injury by PF-04178903

The finding that CCR2 antagonist treatment reduced the number of inflammatory monocytic cells in influenza-infected lungs suggested that it might also reduce lung injury after influenza infection. Initial studies examined prophylactic use of the CCR2 antagonist. Mice were injected with the drug one day before influenza infection (two injections before intra-nasal viral infection). On days 5 and 7 after influenza infection, BAL fluid was collected from control and PF-04178903-treated mice and assayed for markers of lung injury. On day 5, lactose dehydrogenase (LDH) activity and albumin concentrations in BALF were significantly decreased in PF-04178903-treated mice (Fig. 3A&B), while on day 7, albumin and total protein concentration in BALF were significantly decreased (Fig. 3B&C). These data indicate that PF-04178903 prophylaxis can effectively reduce pulmonary pathology in flu-infected lungs. However, these parameters were not reduced in PF-04178903-treated mice to the full extent seen earlier in CCR2-deficient mice (16). CCR2-deficient mice average 60% reductions in total BAL protein and LDH activity on day 5 of influenza infection vs 40% (total BAL protein) and 50% (LDH activity) for PF-04178903-treated mice.

Figure 3.

Influenza-induced lung injury is reduced in PF-04178903-treated mice. Mice were treated with PF-04178903 (PF) or PBS (Ctrl) starting one day before influenza virus inoculation. On day 5 and 7 of influenza infection, mice were sacrificed and their BAL fluid collected and assayed for LDH activity (A), albumin concentration (B), and total protein concentration (C). The value of albumin in BALF from naïve mice is 150 mu;g/ml. The values of LDH activity and total protein concentration for naïve BALF are both near zero. Data is representative of two independent experiments. Bars represent the mean ± SD for 4 or 5 mice per group. p value is calculated by student's t test.

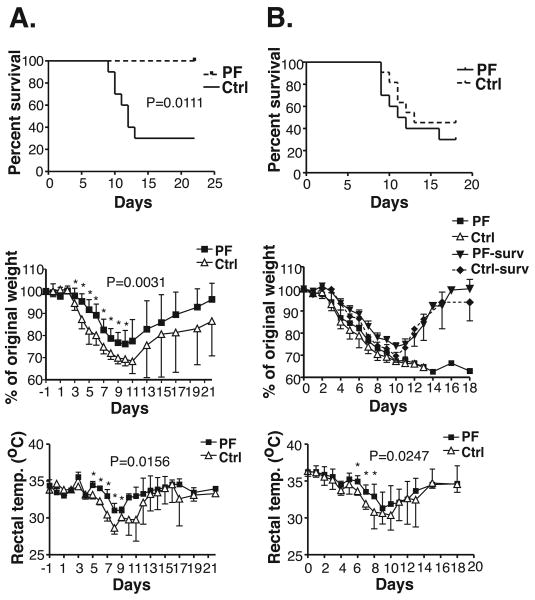

Inhibition of influenza-induced morbidity and mortality by CCR2 antagonist

To determine if the prophylactic use of PF-04178903 could reduce morbidity and mortality in influenza-infected mice, mice were injected with drug one day before influenza infection, twice per day until day 10 after viral inoculation. Mice were weighed and rectal temperatures were measured daily until day 18. This dosing regimen resulted in no influenza-induced mortality, compared to 75% mortality seen in the vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 4A). Drug-treated mice also displayed a significant reduction in weight loss and hypothermia compared to control mice throughout the course of infection (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Influenza-induced morbidity and mortality are reduced by PF-04178903 prophylaxis. Mice were treated s.c. with PF-04178903 or PBS starting one day before (A), or immediately following (B), influenza inoculation and treated twice per day until day 10. Mortality, weight loss, and rectal temperature was monitored daily until day 22. Data is representative of two independent experiments. n = 6∼10 mice. Value of p for the survival curve is calculated by log rank test. P values for overall weight loss and temperature curves were calculated by ANOVA repeated measures. *, p < 0.05 by student's t test comparing individual time points.

To determine if PF-04178903 is effective in reducing mortality when given after influenza infection, mice were treated and monitored as described above except that they were injected with PF-04178903 starting on day 0, immediately after inoculation with influenza virus. PF-04178903 treatment starting on day 0 prolonged mean survival time by about two days but overall mortality was not significantly different between treated and control mice (Fig. 4B). This dosing regimen decreased hypothermia in animals between days 4 and 8 (Fig. 4B). Patterns of weight loss in both control and day 0 treated mice were dependent whether the mice ultimately survived but were not altered by drug treatment in either survivor or non-survivors (Fig. 4B). These data indicate that treatment with PF-04178903 has to be initiated before influenza infection in order to prevent influenza-induced mortality in mice.

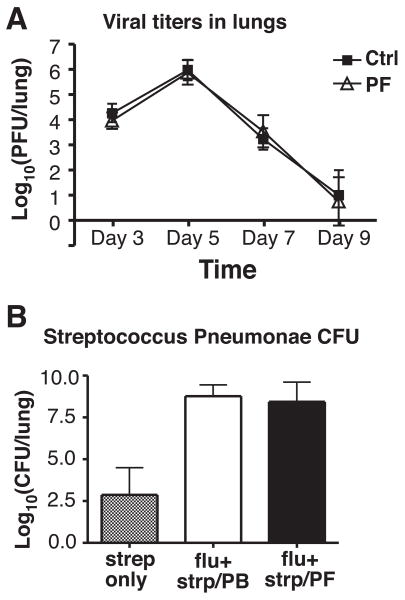

CCR2 antagonist treatment does not increase viral burden or secondary pneumonia infections

To examine whether CCR2 blockade would increase viral burden in infected mice, mice were treated with PF-04178903 starting on day -1, infected with influenza virus on day 0, and whole lungs from infected mice were collected and homogenized on days 3, 5, 7, and 9. As shown in figure 5A, lung viral titers peaked on day 5 and then rapidly decreased to almost undetectable levels on day 9 in both PF-04178903-treated and control (PBS injected) mice. Lung viral titers did not differ significantly between PF-04178903-treated and control mice at any time (Fig. 5A), demonstrating that prophylactic use of a CCR2 inhibitor does not impair viral clearance.

Figure 5.

Neither influenza viral titers nor bacterial loads during secondary streptococcus pneumonae infection are increased in PF-04178903-treated mice. Mice were treated with PF-04178903 or PBS starting one day before influenza inoculation. (A) On infection days 3, 5, 7, and 9, mice were sacrificed and their lung homogenates harvested and subjected to virus plaque forming assays. (B) On day 5 of influenza infection, control and PF-04178903-treated mice were infected with S. pneumonae intranasally, and sacrificed 2 days later. Lung homogenates were serially diluted and plated on agar with sheep blood, and the number of colonies counted. Data is representative of two independent experiments. Bars represent the mean ± SD for 4∼5 mice per group.

Although influenza infection can be lethal itself, many post-influenza deaths are caused by secondary bacterial pneumonias (25). To examine if CCR2 inhibition aggravates secondary bacterial infection with Streptococcus pneumonae, PF-04178903 treatment was started on day -1, and mice were infected with a sublethal dose of H1N1 PR8 strain on day 0, and then inoculated with S. penumoniae intranasally on day 5. Two days later, lung homogenates of infected mice were assayed for bacterial burden. As previously reported (25, 26), influenza infection results in a marked increase in lung bacterial titers (Fig. 5B). However, there was no difference in bacterial burden between PF-04178903-treated and control mice (Fig. 5B), showing that use of a CCR2 antagonist in mice infected with highly pathogenic influenza does not affect the severity of secondary bacterial infection.

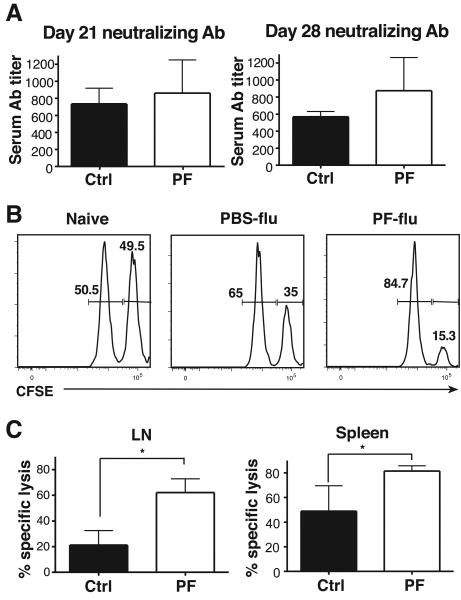

CCR2 antagonist treatment does not decrease viral neutralizing Ab titers or cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses

CCR2-deficient mice, which have decreased numbers of LN monocyte-derived DC, display decreased T helper 1 responses in response to infections (27-30). To determine if CCR2 inhibition results in reduced adaptive immune responses to influenza, we examined anti-influenza neutralizing Ab titers and cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses in PF-04178903-treated mice. Mice were infected with influenza on day 0 and treated with PF-04178903 from day -1 to day 10. Sera were collected for Ab titers on days 21 and 28. As shown in figure 6A, levels of serum anti-influenza neutralizing Abs were comparable in PF-04178903-treated and control mice, suggesting that CCR2 antagonism does not impact the production of viral neutralizing Abs.

Figure 6.

Adaptive immune responses to influenza virus are not impaired in PF-04178903-treated mice. Mice were treated with PF-04178903 or PBS starting one day before influenza inoculation. (A) For virus neutralization assays, mice were treated twice per day until day 10 of infection. Sera from infected mice was collected on days 21 and 28, and assayed for viral neutralizing antibodies. (B&C) For in vivo CTL assays, recipient mice were treated twice per day until day 9 when they received CD45.1 donor splenocytes pulsed with virus nucleoprotein (NP) peptide (labeled CFSEhigh) or OVA peptide (labeled CFSElow). Recipient mice were euthanized 6 hours after adoptive transfer and their spleens and LN harvested. Naïve mice were used as controls. Cells from draining mediastinal LN and spleens were analyzed for the presence of CFSEhigh and CFSElow target cell populations. The flow data from spleens is shown in (B). To quantify in vivo cytotoxicity, the elimination of the NP-pulsed CFSEhigh population was monitored and the percentage of specific lysis (C) was determined as described in materials and methods. Data is representative of two independent experiments. Bars represent the mean ± SD for 4∼5 mice per group. *, p < 0.05 by student's t test.

For in vivo CTL assays, recipient mice were treated with PF-04178903 and infected with influenza as above. On day 9, donor splenocytes were pulsed with viral nucleoprotein peptide or an unrelated peptide, the two cell populations differentially labeled with CFSE, and the labeled cells transferred to recipient mice. Six hours later, the mice were sacrificed and the presence of donor cells in mediastinal LNs and spleens was assessed. A greater proportion of NP-pulsed (CSFEhi) cells were eliminated from the spleens (Fig. 6B) and mediastinal LNs (data not shown) in PF-04178903-treated mice than in control mice, leading to a significantly increased calculated CTL activity in PF-04178903-treated mice (Fig. 6C). Interestingly, NP-specific CTL activity was higher in spleens than in mediastinal LNs (Fig. 6C), demonstrating that antigen-specific CD8+ T cells distribute systematically after generation, and that this is not inhibited by CCR2 antagonism. We conclude that CCR2 inhibition with small molecule inhibitors does not reduce CTL activity against influenza virus, but actually enhances it.

Discussion

Infection with highly pathogenic influenza virus causes significant pulmonary immune pathology. To date, no drugs have been reported as being effective in preventing or treating this pathology. In this report, we demonstrate that CCR2 inhibition in adult mice can decrease influenza-induced pulmonary immune pathology and mortality. The small molecule CCR2 inhibitor PF-04178903 used prophylactically to treat mice with severe influenza infection results in decreased recruitment/accumulation of monocyte-derived cells in the lungs and reduced lung injury as measured by LDH activity, albumin concentration, and total protein concentration in BALF. PF-01478903 treatment also results in decreased weight loss, decreased hypothermia, and a 100% survival rate, a marked improvement when compared to control mice. These results are consistent with earlier influenza infection studies conducted in CCR2-deficient mice (16, 20). The correlation of a decreased number of inflammatory monocytic cells in the lungs and reduced pulmonary damage suggests that CCR2 inhibition diminishes morbidity and mortality by blocking the accumulation of inflammatory monocytes in influenza-infected lungs.

Prophylactic use of the CCR2 inhibitor PF-04178903 does not result in any apparent side effects. We find no decrease in immunity against influenza virus or increase in severity of secondary bacterial infection. Drug-treated mice exhibit comparable levels of viral titers, influenza-specific neutralizing Ab titers, and bacteria loads after secondary bacteria infections when compared with control mice. Unexpectedly, the prophylactic dosing of PF-04178903 results in increased CTL activity against influenza virus protein-loaded cells. Multiple DC subsets have been shown to present viral antigen to CD4 T cells (31). CD8+ DC and CD103+ migrating lung DC are specifically implicated in the induction of CD8+ virus-specific T cells (32, 33). Thus, although moDC are likely to play a role in T cell activation during influenza infection, it appears that other DC subsets that are not CCR2-dependent are sufficient to perform this function. We speculate that the high levels of cytokines produced by monocyte-derived DC and ExMACs during influenza infection may interfere with normal T cell activation. It has been shown that overproduction of NO during viral infections can suppress Th1 responses, leading to Th2-biased immune responses (18, 34-36). This may result in fewer cytotoxic T cells being primed (37, 38). Decreased iNOS expression was seen in CCR2-deficient mice (16), and is likely to occur in PF-04178903-treated mice. This may explain the increased CTL activity in drug-treated mice.

We observed that drug-treated mice do not have increased bacterial burdens after secondary S.pnuemococcus infection. This finding was somewhat unexpected because CCR2-deficient mice have been shown to have decreased resistance to some bacterial infections, an effect that is probably due to a decreased number of macrophages in infected tissues (9, 10). However, macrophages in influenza-infected lungs appear to be dysfunctional and therefore of little benefit in the clearance of bacteria. This would explain the markedly increased susceptibility of influenza-infected mice to bacterial infection (25). It appears that reducing the numbers of such dysfunctional cells has little effect on bacterial clearance. Macrophage dysfunction may be caused by the abnormal elevation of both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines elicited by influenza infections (25). IL-10 has been proposed to be the key mediator for this dysfunctional process: inhibiting IL-10 in flu-infected mice improves the survival rate from secondary bacteria infections (39, 40). Moreover, others have reported that the decreased migration of neutrophils, along with the reduced phagocytosis and reactive oxygen species generation in neutrophils during influenza infections, contribute to the failure to clear secondary bacteria infections (26, 41, 42). It seems that, with limited neutrophil functions, the bacteria infection is difficult to control with or without the help of macrophages.

Interestingly, administration of PF-04178903 after influenza infection of mice did not reduce either overall mortality or morbidity. The reason that PF-04178903 failed as a therapeutic is not clear. The most obvious cause of decreased efficacy in mice treated after infection would be a decrease in the inhibition of inflammatory monocyte accumulation in lungs. However, we found no significant differences in inflammatory cell accumulation in the lungs of mice treated at day -1 versus those treated at day 0 (data not shown). Still, we cannot rule out the possibility that a small number of monocytes, capable of inducing injury, enter lungs vey early in the course of infection in day 0 treated mice but fall below the limits of our detection. It is also possible treatment with PF-04178903 inhibits the function or activation of inflammatory monocytes at baseline but that this effect is lost once these cells are activated by influenza virus. Such “timing” effects would be due to fundamental aspects of CCR2 biology and would be expected with any CCR2 antagonist. Alternatively, it is possible that the lack of efficacy of PF-04178903 treatment after infection is due to some unrecognized characteristic of this specific compound and that some other CCR2 antagonist may perform better when used as a treatment. We are currently examining these possibilities.

Small molecule CCR2 antagonists have been tested in several murine models of inflammatory diseases, including experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), adjuvant arthritis, dry eye disease, and hepatic steatosis and lipoatrophy (44-46). In these models, CCR2 antagonist treatment reduces the accumulation of monocyte-derived cells in target organs, decreases inflammation, and maintains organ functions. Here, we show that prophylactic CCR2 inhibition reduces the excessive immune responses that occur during influenza infection. To our knowledge, this is the first instance in which CCR2 antagonists have been used to reduce infection-induced immune pathology. Our results suggest that CCR2 inhibition may be useful in other infection-induced inflammatory diseases.

Although current antiviral drugs can be effective in treating highly pathogenic influenza infection, they must be used early in the course of infection (7). The CCR2 inhibitor used in our study also has to be administered early to prevent subsequent mortality. In our model, mortality was not caused by high viral load. Viral titers actually dropped before inflammation peaked. In contrast, human H5N1 avian flu infections are often associated with continued high viral loads in alveolar epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages and blocking viral replication appears to be critical for patient survival (7, 8). It is possible that the combined use of anti-viral drugs and CCR2 inhibitors would be more successful in blocking immune pathology later in the course of influenza infection, since combined therapy would block viral replication and inflammation at the same time. Therefore, while CCR2 inhibition has a potential to be used as prophylaxis, it should also be evaluated in the later course of infection along with antiviral drugs.

Supplementary Material

Suppl.Figure 1. FSC/SSC of Cell populations in the lungs of influenza-infected mice. Mice were infected by inoculating influenza virus PR8 intranassally. After 5 days, the lungs were digested and processed for flow analysis. FSC/SSC of each cell populations is shown.

Acknowledgments

We thank Philip Morton and Pfizer Inc. for the generous gift of compound PF-04178903, and the Duke Human Vaccine Institute Flow Cytometry Facility for their continued support.

Nonstandard abbreviations

- DC

dendritic cells

- exMAC

exudative macrophage

- AM

alveolar macrophage

- PMN

polymorphonuclear cells neutrophils

- NO

nitric oxide

- BAL

bronchoalveolar lavage

- LDH

lactose dehydrogenase

- NP

influenza nucleoprotein peptide

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH grant U01AI074529.

References

- 1.La Gruta NL, Kedzierska K, Stambas J, Doherty PC. A question of selfpreservation: immunopathology in influenza virus infection. Immunol Cell Biol. 2007;85:85–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Doherty PC, Turner SJ, Webby RG, Thomas PG. Influenza and the challenge for immunology. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:449–455. doi: 10.1038/ni1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patterson S. The pathology of influenza in France. The medical journal of Australia. 1920;1 [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Jong MD, Simmons CP, Thanh TT, Hien VM, Smith GJ, Chau TN, Hoang DM, Chau NV, Khanh TH, Dong VC, Qui PT, Cam BV, Ha do Q, Guan Y, Peiris JS, Chinh NT, Hien TT, Farrar J. Fatal outcome of human influenza A (H5N1) is associated with high viral load and hypercytokinemia. Nat Med. 2006;12:1203–1207. doi: 10.1038/nm1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peiris JS, Yu WC, Leung CW, Cheung CY, Ng WF, Nicholls JM, Ng TK, Chan KH, Lai ST, Lim WL, Yuen KY, Guan Y. Re-emergence of fatal human influenza A subtype H5N1 disease. Lancet. 2004;363:617–619. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15595-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.To KF, Chan PK, Chan KF, Lee WK, Lam WY, Wong KF, Tang NL, Tsang DN, Sung RY, Buckley TA, Tam JS, Cheng AF. Pathology of fatal human infection associated with avian influenza A H5N1 virus. J Med Virol. 2001;63:242–246. doi: 10.1002/1096-9071(200103)63:3<242::aid-jmv1007>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdel-Ghafar AN, Chotpitayasunondh T, Gao Z, Hayden FG, Nguyen DH, de Jong MD, Naghdaliyev A, Peiris JS, Shindo N, Soeroso S, Uyeki TM. Update on avian influenza A (H5N1) virus infection in humans. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:261–273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maines TR, Szretter KJ, Perrone L, Belser JA, Bright RA, Zeng H, Tumpey TM, Katz JM. Pathogenesis of emerging avian influenza viruses in mammals and the host innate immune response. Immunol Rev. 2008;225:68–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peters W, Scott HM, Chambers HF, Flynn JL, Charo IF, Ernst JD. Chemokine receptor 2 serves an early and essential role in resistance to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7958–7963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131207398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurihara T, Warr G, Loy J, Bravo R. Defects in macrophage recruitment and host defense in mice lacking the CCR2 chemokine receptor. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1757–1762. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.10.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winter C, Taut K, Srivastava M, Langer F, Mack M, Briles DE, Paton JC, Maus R, Welte T, Gunn MD, Maus UA. Lung-specific overexpression of CC chemokine ligand (CCL) 2 enhances the host defense to Streptococcus pneumoniae infection in mice: role of the CCL2-CCR2 axis. J Immunol. 2007;178:5828–5838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matthay MA, Zimmerman GA. Acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome: four decades of inquiry into pathogenesis and rational management. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:319–327. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.F305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rose EJ, Sung S, Fu S. Significant involvement of CCL2 (MCP-1) in inflammatory disorders of the lung. Microcirculation. 2003;10:273–288. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okuma T, Terasaki Y, Kaikita K, Kobayashi H, Kuziel WA, Kawasuji M, Takeya M. C-C chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) deficiency improves bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis by attenuation of both macrophage infiltration and production of macrophage-derived matrix metalloproteinases. J Pathol. 2004;204:594–604. doi: 10.1002/path.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dawson TC, Beck MA, Kuziel WA, Henderson F, Maeda N. Contrasting effects of CCR5 and CCR2 deficiency in the pulmonary inflammatory response to influenza A virus. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1951–1959. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65068-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lin KL, Suzuki Y, Nakano H, Ramsburg E, Gunn MD. CCR2+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells and exudate macrophages produce influenza-induced pulmonary immune pathology and mortality. J Immunol. 2008;180:2562–2572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis I, Matalon S. Reactive species in viral pneumonitis: lessons from animal models. News Physiol Sci. 2001;16:185–190. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2001.16.4.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akaike T, Maeda H. Nitric oxide and virus infection. Immunology. 2000;101:300–308. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peper RL, Van Campen H. Tumor necrosis factor as a mediator of inflammation in influenza A viral pneumonia. Microb Pathog. 1995;19:175–183. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1995.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herold S, Steinmueller M, von Wulffen W, Cakarova L, Pinto R, Pleschka S, Mack M, Kuziel WA, Corazza N, Brunner T, Seeger W, Lohmeyer J. Lung epithelial apoptosis in influenza virus pneumonia: the role of macrophage-expressed TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. J Exp Med. 2008;205:3065–3077. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geissmann F, Auffray C, Palframan R, Wirrig C, Ciocca A, Campisi L, Narni- Mancinelli E, Lauvau G. Blood monocytes: distinct subsets, how they relate to dendritic cells, and their possible roles in the regulation of T-cell responses. Immunol Cell Biol. 2008;86:398–408. doi: 10.1038/icb.2008.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunn MD, Nelken NA, Liao X, Williams LT. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 is sufficient for the chemotaxis of monocytes and lymphocytes in transgenic mice but requires an additional stimulus for inflammatory activation. J Immunol. 1997;158:376–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coles RM, Mueller SN, Heath WR, Carbone FR, Brooks AG. Progression of armed CTL from draining lymph node to spleen shortly after localized infection with herpes simplex virus 1. J Immunol. 2002;168:834–838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsou CL, Peters W, Si Y, Slaymaker S, Aslanian AM, Weisberg SP, Mack M, Charo IF. Critical roles for CCR2 and MCP-3 in monocyte mobilization from bone marrow and recruitment to inflammatory sites. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:902–909. doi: 10.1172/JCI29919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCullers JA. Insights into the interaction between influenza virus and pneumococcus. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:571–582. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00058-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shahangian A, Chow EK, Tian X, Kang JR, Ghaffari A, Liu SY, Belperio JA, Cheng G, Deng JC. Type I IFNs mediate development of postinfluenza bacterial pneumonia in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1910–1920. doi: 10.1172/JCI35412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luther SA, Cyster JG. Chemokines as regulators of T cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:102–107. doi: 10.1038/84205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Traynor TR, Kuziel WA, Toews GB, Huffnagle GB. CCR2 expression determines T1 versus T2 polarization during pulmonary Cryptococcus neoformans infection. J Immunol. 2000;164:2021–2027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sato N, Ahuja SK, Quinones M, Kostecki V, Reddick RL, Melby PC, Kuziel WA, Ahuja SS. CC chemokine receptor (CCR)2 is required for langerhans cell migration and localization of T helper cell type 1 (Th1)-inducing dendritic cells. Absence of CCR2 shifts the Leishmania major-resistant phenotype to a susceptible state dominated by Th2 cytokines, b cell outgrowth, and sustained neutrophilic inflammation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:205–218. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters W, Dupuis M, Charo IF. A mechanism for the impaired IFN-gamma production in C-C chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) knockout mice: role of CCR2 in linking the innate and adaptive immune responses. J Immunol. 2000;165:7072–7077. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.7072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mount AM, Smith CM, Kupresanin F, Stoermer K, Heath WR, Belz GT. Multiple dendritic cell populations activate CD4+ T cells after viral stimulation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belz GT, Smith CM, Kleinert L, Reading P, Brooks A, Shortman K, Carbone FR, Heath WR. Distinct migrating and nonmigrating dendritic cell populations are involved in MHC class I-restricted antigen presentation after lung infection with virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:8670–8675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402644101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim TS, Braciale TJ. Respiratory dendritic cell subsets differ in their capacity to support the induction of virus-specific cytotoxic CD8+ T cell responses. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei XQ, Charles IG, Smith A, Ure J, Feng GJ, Huang FP, Xu D, Muller W, Moncada S, Liew FY. Altered immune responses in mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase. Nature. 1995;375:408–411. doi: 10.1038/375408a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor-Robinson AW, Liew FY, Severn A, Xu D, McSorley SJ, Garside P, Padron J, Phillips RS. Regulation of the immune response by nitric oxide differentially produced by T helper type 1 and T helper type 2 cells. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:980–984. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karupiah G, Chen JH, Mahalingam S, Nathan CF, MacMicking JD. Rapid interferon gamma-dependent clearance of influenza A virus and protection from consolidating pneumonitis in nitric oxide synthase 2-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1541–1546. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mehrotra PT, Wu D, Crim JA, Mostowski HS, Siegel JP. Effects of IL- 12 on the generation of cytotoxic activity in human CD8+ T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1993;151:2444–2452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simon MM, Hochgeschwender U, Brugger U, Landolfo S. Monoclonal antibodies to interferon-gamma inhibit interleukin 2-dependent induction of growth and maturation in lectin/antigen-reactive cytolytic T lymphocyte precursors. J Immunol. 1986;136:2755–2762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van der Sluijs KF, van Elden LJ, Nijhuis M, Schuurman R, Pater JM, Florquin S, Goldman M, Jansen HM, Lutter R, van der Poll T. IL-10 is an important mediator of the enhanced susceptibility to pneumococcal pneumonia after influenza infection. J Immunol. 2004;172:7603–7609. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Poll T, Marchant A, Keogh CV, Goldman M, Lowry SF. Interleukin-10 impairs host defense in murine pneumococcal pneumonia. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:994–1000. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McNamee LA, Harmsen AG. Both influenza-induced neutrophil dysfunction and neutrophil-independent mechanisms contribute to increased susceptibility to a secondary Streptococcus pneumoniae infection. Infect Immun. 2006;74:6707–6721. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00789-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sprenger H, Meyer RG, Kaufmann A, Bussfeld D, Rischkowsky E, Gemsa D. Selective induction of monocyte and not neutrophil-attracting chemokines after influenza A virus infection. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1191–1196. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Serbina NV, Pamer EG. Monocyte emigration from bone marrow during bacterial infection requires signals mediated by chemokine receptor CCR2. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:311–317. doi: 10.1038/ni1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang SJ, IglayReger HB, Kadouh HC, Bodary PF. Inhibition of the chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2/chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 2 pathway attenuates hyperglycaemia and inflammation in a mouse model of hepatic steatosis and lipoatrophy. Diabetologia. 2009;52:972–981. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goyal S, Chauhan SK, Zhang Q, Dana R. Amelioration of murine dry eye disease by topical antagonist to chemokine receptor 2. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:882–887. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brodmerkel CM, Huber R, Covington M, Diamond S, Hall L, Collins R, Leffet L, Gallagher K, Feldman P, Collier P, Stow M, Gu X, Baribaud F, Shin N, Thomas B, Burn T, Hollis G, Yeleswaram S, Solomon K, Friedman S, Wang A, Xue CB, Newton RC, Scherle P, Vaddi K. Discovery and pharmacological characterization of a novel rodent-active CCR2 antagonist, INCB3344. J Immunol. 2005;175:5370–5378. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Suppl.Figure 1. FSC/SSC of Cell populations in the lungs of influenza-infected mice. Mice were infected by inoculating influenza virus PR8 intranassally. After 5 days, the lungs were digested and processed for flow analysis. FSC/SSC of each cell populations is shown.