Abstract

km23-1 was previously identified as a TGFß-receptor interacting protein that was phosphorylated on serines after TGFß stimulation. In the current report, we examined the role of km23-1 phosphorylation in the downstream effects of TGFß/ protein kinase A (PKA) signaling. Using phosphorylation site prediction software, we found that km23-1 has two potential PKA consensus phosphorylation sites. In vitro kinase assays further demonstrated that PKA directly phosphorylates km23-1 on serine 73 (S73). Moreover, our results show that the PKA-specific inhibitor H89 diminishes phosphorylation of km23-1 on S73 after TGFß stimulation. Taken together, our results demonstrate that TGFß induction of PKA activity results in phosphorylation of km23-1 on S73. In order to assess the mechanisms underlying PKA phosphorylation of km23-1 on S73 (S73-km23-1) after TGFß stimulation, immunoprecipitation (IP)/blot analyses were performed, which demonstrate that TGFß regulates complex formation between the PKA regulatory subunit RIß and km23-1 in vivo. In addition, an S73A mutant of km23-1 (S73A-km23-1), which could not be phosphorylated by PKA, inhibited TGFß induction of the km23-1-dynein complex and transcriptional activation of the activin-responsive element (ARE). Furthermore, our results show that km23-1 is required for cAMP-responsive element (CRE) transcriptional activation by TGFß, with S73-km23-1 being required for the CRE-dependent TGFß stimulation of fibronectin (FN) transcription. Collectively, our results demonstrate for the first time that TGFß/PKA phosphorylation of km23-1 on S73 is required for ARE- and CRE-mediated downstream events that include FN induction.

Keywords: TGFß, km23-1, protein kinase A, phosphorylation, signal transduction

Introduction

The transforming growth factor (TGFß) superfamily is a large family of structurally related cell regulatory proteins that are differentially expressed and regulates diverse cellular processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, fibrosis, wound repair, and inflammation in a wide range of target cells (Kang et al., 2009; Mu et al., 2012; Padua and Massague, 2009; Yue and Mulder, 2001). To initiate signaling, TGFß binds to and brings together type I (TßRI) and type II (TßRII) TGFß serine/threonine kinase receptors on the cell surface, followed by transphosphorylation of TßRI. The activated receptor complex stimulates intracellular mediators of TGFß signaling, including receptor-activated Smads (RSmads). These activated RSmads can form a complex with the common partner Smad4 and translocate to the nucleus, where they regulate transcription of a wide range of target genes (Kang et al., 2009; Padua and Massague, 2009). Besides the Smad-dependent pathway, TGFß signaling involves the activation of a number of other signaling pathways, including Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/ AKT, and PKA (Kang et al., 2009; Mu et al., 2012; Mulder, 2000; Padua and Massague, 2009; Yue and Mulder, 2001; Zhang, 2009).

PKA is a cytosolic, tetrameric holoenzyme that is composed of two regulatory subunits associated with two catalytic subunits in its inactive state (Taylor et al., 1990; Zhang et al., 2012). PKA signaling has been shown to play an important role in multiple physiological processes, including growth, differentiation, extracellular matrix production, cell motility, and apoptosis (Howe, 2011; Kotani, 2012; Walsh and Van Patten, 1994). TGFß also regulates many of these cellular processes, and there are several lines of evidence demonstrating interactions between TGFß signaling pathways and PKA. For example, previous results have shown that TGFß stimulates PKA signaling events in both mesangial and mink lung epithelial (Mv1Lu) cells that involve TGFß stimulation of cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) phosphorylation and fibronectin (FN) induction (Wang et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2004). In addition, TGFß induction of a Smad3/Smad4 complex has been shown to directly activate PKA independent of increased cAMP in Mv1Lu cells (Zhang et al., 2004). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the interaction of TGFß and PKA signaling pathways are still not fully understood.

We have previously identified km23-1 as a TGFß receptor-interacting protein in a novel screen (Tang et al., 2002). km23-1, also termed km23 (Campbell et al., 2006; Kang et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2002), Robl1 (Nikulina et al., 2004), DNLC2A (Jiang et al., 2001), mLC7-1 (Tang et al., 2002), DYNLRB1, (Pfister et al., 2005) has been shown to interact with Rab6 (Wanschers et al., 2008), the human reduced folate carrier (Ashokkumar et al., 2009), dynein intermediate chain (DIC) (Susalka et al., 2002; Tang et al., 2002), and LIN-5 and GPR-1/2 in C. elegans (Couwenbergs et al., 2007). We have shown that km23-1 undergoes rapid phosphorylation on serine residues after TßR activation, in keeping with the kinase specificity of the TßRs (Tang et al., 2002). Moreover, overexpression of km23-1 in TGFß-responsive Mv1Lu cells induced specific TGFß responses, such as Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation and c-Jun phosphorylation (Jin et al., 2005). Furthermore, blockade of km23-1 decreased cellular responses to TGFß, including induction of FN expression and inhibition of cell cycle progression (Jin et al., 2005). Additional studies demonstrated that km23-1 can be a signaling mediator for Smad2-dependent TGFß signaling in mammalian cells (Jin et al., 2007). However, the mechanisms underlying km23-1's regulatory role in these major TGFß events is unclear. In the current report, we examined whether PKA could phosphorylate km23-1 in response to TGFß, and further, whether this phosphorylation could regulate specific TGFß/PKA pathway targets such as CRE and FN transcription.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

TGFß1 was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The FuGENE 6 transfection reagent was from Roche Applied Science. The Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (E1960) was purchased from Promega (Madison, MI). The QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit was from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). The mouse IgG was from Sigma-Aldrich, and the rabbit IgG was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The anti-DIC monoclonal antibody (Ab) (MAB1618) was from Chemicon (Temecula, CA). The anti-FLAG M2 (F3165) Ab was from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). γ-[32P]ATP (BLU002H) was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA). The PKA inhibitor H89 was from Calbiochem. The anti-PKA RIß Ab was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). The rabbit hkm23-1 (1-15) and hkm23-1(27-43)w Abs were described previously (Jin et al., 2007; Jin et al., 2005). Pathdetect CRE-Luc cis-reporter plasmid was from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA, USA).

Constructs

The Flag-tagged serine mutants of km23-1, S32A-km23-1 and S73A-km23-1, were produced using the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene) from Flag-tagged km23-1 (Tang et al., 2002) following the manufacturer's protocols. His-tagged S32A-km23-1 and S73A-km23-1 constructs were produced using the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit from His-tagged km23-1 (Ilangovan et al., 2005). The Flag-tagged ΔS32A-km23-1 construct was produced using the QuickChange Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit from Flag-tagged Δkm23-1 (Jin et al., 2007). The V5-tagged RI construct was generated by inserting the Alk-5 RI cDNA fragment (provided by Dr. K. Miyazono), University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan), which was prepared by NotI and XhoI restriction enzyme digestion, into pcDNA3.1/V5-His (V-810-20; Invitrogen). The HA-tagged RII construct was provided by Dr. J. Wrana (Samuel Lunenfeld Res. Institute, Toronto, Canada). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing in both directions.

Cell culture

Mv1Lu (CCL-64) and 293T cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and were grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium with 10% (v/v) heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. Cells were maintained in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Cultures were routinely screened for mycoplasma using Hoechst 33258 staining.

Antibody production

The anti-serine-73 phospho-specific Ab (S73-P-km23-1) was custom-generated in rabbits by Anaspec (San Jose, CA), prepared against the phosphospecific serine-73 peptide (TFLRIR (pS) KKNE-NH2) conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH). The S73-P-km23-1 was further purified by positive-selection affinity chromatography using the phospho-peptides and by negative-depletion using nonphospho-peptides (TFLRIR S KKNE-NH2). Transient transfections, in vivo phosphorylation assays, immunoprecipitation (IP)/blot, and Westerns were performed essentially as described previously (Jin et al., 2007; Jin et al., 2005; Jin et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2002).

In vitro kinase assays

To measure in vitro km23-1 phosphorylation by PKA, 12 ug of purified His-km23-1 fusion protein and 10 μCi of γ-32P ATP (from PerkinElmer) were added to buffer provided by a PKA assay kit (Upstate). For PKA assays, three different concentrations (10 ng, 20 ng, or 40 ng) of the catalytic subunit of PKA (Upstate) were examined. 5 μM of PKA inhibitory peptide (PKI) (Bachem) was included in one reaction with 20 ng of PKA as a negative control. Kinase reactions were conducted at 30°C for 30 min and terminated by the addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer. The proteins were subjected to 15% SDS-PAGE and 32P-labled fusion proteins were detected by autoradiography.

Luciferase reporter assays

For ARE-Lux assays, Mv1Lu cells were co-transfected with ARE-Lux and FAST-1 (Felici et al., 2003; Jin et al., 2007; Piek et al., 2001; Yeo et al., 1999). TGFß-dependent SBE2-Luc, CRE-Luc, and pFN-Luc reporter assays were performed as described previously (Jin et al., 2007) using either FuGene 6 (Roche, Cat# 11814443001) or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Renilla was used to normalize transfection efficiencies. 24 h after transfection, the cells were washed once with serum-free (SF) medium and incubated in SF medium for 1 h prior to TGFß1 (10 ng/ml) treatment for an additional 18 h. Luciferase activity was measured using Promega's Dual-luciferase Reporter Assay System following the manufacturer's instructions. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analyses were by Student's t test. Triplicate samples were analyzed and mean ± SE plotted unless otherwise indicated.

Results

Our previous results have shown that km23-1 is a TGFß signaling component that associates with the activated TGFß receptor (TßR) complex endogenously, and is phosphorylated on serine residues (Tang et al., 2002). In order to identify other putative kinases that may phosphorylate km23-1, besides the TßR kinase, we used NetPhosK 1.0 to predict the potential phosphorylation sites in the km23-1 sequence. Previous studies have shown that for a given specificity level, NetPhosK-PKA achieves a higher sensitivity rate compare to other prediction methods (Blom et al., 2004). Using NetPhosK1.0, two potential PKA consensus phosphorylation sites were identified in the km23-1 sequence. One of the PKA consensus sites covers serine 13 (S13) (0.52, with the maximum of 1) and the other starts with serine 73 (S73) (0.76, with the maximum of 1). The maximum values indicate best overall prediction performance (Blom et al., 2004). Thus, the prediction results suggest that PKA might be another potential kinase for km23-1 besides the TßRs.

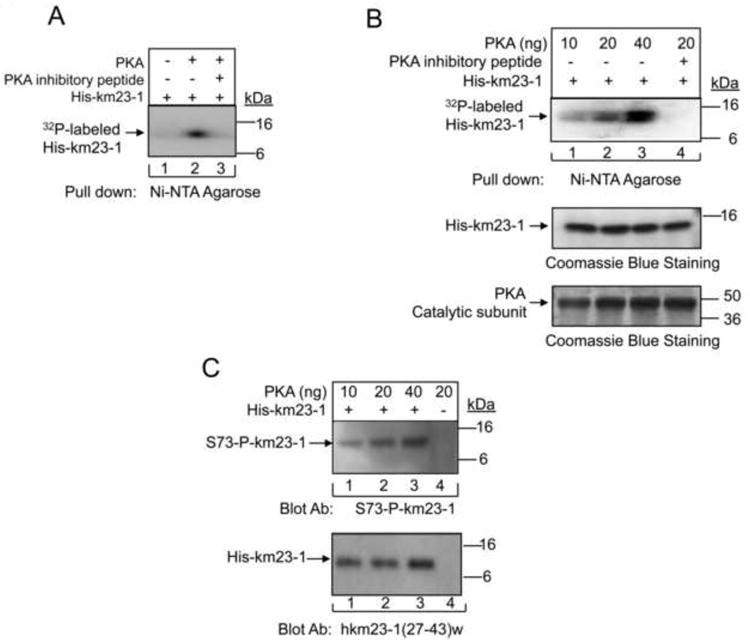

In order to determine whether PKA is a direct kinase of km23-1, we performed in vitro kinase assays with the catalytic subunit of PKA as the kinase, and purified His-km23-1 protein as the substrate. As shown in Fig. 1A, PKA directly phosphorylated km23-1 in vitro (lane 2). A PKA inhibitory peptide completely blocked the phosphorylation of km23-1 by PKA (lane 3). No signal was detected in the absence of both PKA and PKA inhibitory peptide (lane 1). Similarly, the top panel of Fig. 1B further shows the direct phosphorylation of km23-1 by PKA in a dose-dependent manner (top panel, lanes 1-3). As expected, the PKA inhibitory peptide (5 μM) completely blocked the phosphorylation of km23-1 by PKA (top panel, lane 4). Lower panels show Coomassie blue staining of the expression of His-km23-1 fusion proteins and equal loading of the PKA catalytic subunit. Thus, our results demonstrate that PKA is able to directly phosphorylate km23-1 in vitro. Our previous results and those of others have shown that both S13 and S73 are conserved and are located on the surface (Hall et al., 2010; Ilangovan et al., 2005), which suggested that they might play important roles in protein function. Since the prediction results indicated that S73 scored higher than S13, we hypothesized that S73 was the major PKA phosphorylation site in km23-1.

Fig. 1. PKA directly phosphorylates km23-1 on S73 in vitro.

A: Purified His-km23-1 fusion proteins were used as substrates in an in vitro kinase reaction with the recombinant catalytic subunit of PKA in the presence of [γ-32P] ATP. B: Similar studies were performed as for A except with increasing amounts of the recombinant catalytic subunit of PKA used. Equal loading of His-km23-1 fusion proteins and of the catalytic subunit of PKA were revealed by Coomassie blue staining in the lower panels. C: After pull-down using Ni-NTA agarose followed by SDS-PAGE as for A, the His-fusion proteins were detected by blotting with the S73 phospho-specific km23-1 Ab. Lower panel, Western blot analysis showing equal loading of His-km23-1 using km23-1 (27-43)w Ab. The results are representative of triplicate experiments.

In order to determine whether PKA could directly phosphorylate km23-1 at S73, we generated a S73 phospho-specific Ab (S73-P-km23-1) against the phospho-S73 peptide (TFLRIR (pS) KKNE-NH2). Furthermore, we performed in vitro kinase assays as described for Fig. 1B, and then blotted the membrane with the S73 phospho-specific anti-km23-1 Ab (S73-P-km23-1). As shown in Fig. 1C, phosphorylation detected by the S73-P-km23-1 Ab is also dependent upon the dose of PKA. It is clear that the level of S73-km23-1 phosphorylation was increased with the addition of the PKA catalytic subunit over the concentration range of 0.01 - 0.04 μg (lanes 1-3, top panel). Collectively, our results demonstrate that PKA directly phosphorylates km23-1 on S73.

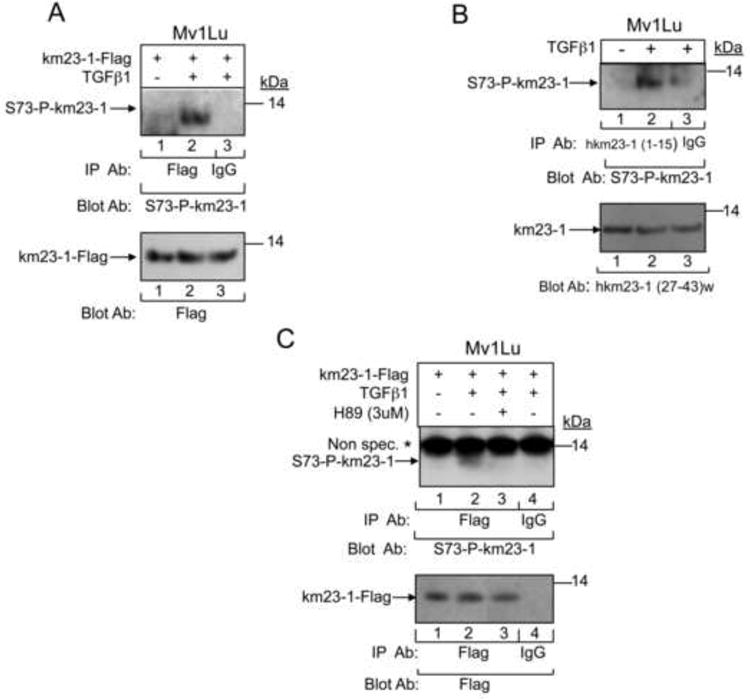

Previous studies have shown that PKA plays important roles in TGFß signaling (Wang et al., 1998; Yang et al., 2008). In addition, our results have shown that km23-1 is directly phosphorylated by PKA on S73 in vitro. Therefore, it was of interest to determine whether PKA could phosphorylate km23-1 on S73 in response to TGFß receptor activation in Mv1Lu cells. Accordingly, we performed IP/blot analyses using a Flag Ab as the IP Ab and an anti-S73 phospho-km23-1 Ab as the blotting Ab, in the absence and presence of TGFß. As shown in Fig. 2A, TGFß treatment affected the phosphorylation of km23-1, in contrast to no detectable phosphorylation in the absence of TGFß. Our results in Fig. 2B further confirmed that endogenous km23-1 is phosphorylated on S73 after TGFß treatment. To determine whether TGFß induction of km23-1 phosphorylation on S73 was PKA-specific, the cells were treated with the PKA-specific inhibitor H89 (Fig. 2C). H89 has been used in recent reports from other laboratories to implicate PKA in various signaling events (Maymo et al., 2012; Park et al., 2012). While phosphorylated km23-1-Flag was detectable with the S73-P-km23-1 Ab by 30 min after TGFß treatment (top panel, lane 2), no corresponding band was observed with H89 treatment (top panel, lane 3). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that PKA phosphorylates km23-1 on S73 in vivo in response to TGFß.

Fig. 2. TGFß induces PKA phosphorylation of km23-1 on S73 in vivo, which is inhibited by H89.

A: Mv1Lu cells were transfected with km23-1-Flag. 24h later cells were changed to SF conditions for 1 h prior to TGFß1 (10 ng/ml) treatment for 30 min. Cell lysates were subjected to IP using a Flag Ab, and blotted using the S73 phospho-specific anti-km23-1 antibody (S73-P-km23-1). Lower panel, Western blot analysis showing equal expression of km23-1-Flag using anti-Flag. The results are representative of triplicate experiments. B: Endogenous km23-1 was IP'd using hkm23-1 (1-15) Ab, and blotted using S73-P-km23-1. Lower panel, Western blot analysis showing equal expression of endogenous km23-1 using km23-1(27-43)w Ab. C: Mv1Lu cells were transfected with km23-1-Flag, and treated with TGFß1 as for A. For lane 3, cells were treated with H89 for 30 min prior to TGFß1 treatment for 30 min. Cell lysates were treated and analyzed as for A. Lane 4 is the IgG control. The results are representative of triplicate experiments.

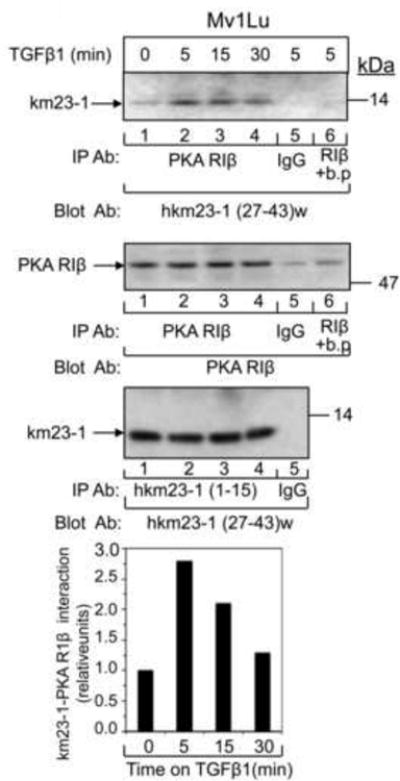

Regulation by PKA usually involves localization of the PKA regulatory complex in direct proximity to its substrates. Since our results have shown that PKA directly phosphorylates km23-1 on S73 in response to TGFß, it was of interest to determine whether km23-1 interacts with the PKA regulatory subunit in the absence and presence of TGFß. Accordingly, we performed IP/blot analyses using an Ab against the RIß regulatory subunit of PKA, and blotted with a rabbit anti human km23-1 [hkm23-1(27-43)w] Ab. The RIß isoform was used since it was previously shown to bind Smads following TGFß activation in Mv1Lu cells (Zhang et al., 2004). As shown in Fig. 3, endogenous km23-1 was observed to be present in a complex with PKA RIß in a TGFß-dependent manner, as early as 5 min after TGFß (top panel, lane 2), with a decrease at 30 min (top panel, lane 4). This time course is similar to that for the TGFß-induced PKA-Smad interaction (5-30 min) (Yang et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2004), suggesting that the formation of the complex between km23-1 and PKA R1ß occurs during the time when PKA is activated by TGFß.

Fig. 3. km23-1 interacts with the R1ß regulatory subunit of PKA in a TGFß-dependent manner.

Mv1Lu cells were washed once with SF medium and incubated in SF medium for 1 h prior to TGFß1 (10 ng/ml) treatment for the indicated times. Cell lysates (500 μg) were used for IP with 1 μg of anti-PKA RIß subunit Ab, and were then blotted with an anti-hkm23-1 (27-43)w Ab (top panel). The same membrane was then blotted with the PKA RIß subunit Ab to show equal IP'd proteins (1st middle panel, lane 1-4). Lane 6 is the negative control for the IP Ab in which an RIß blocking peptide (b.p.) was added to the cell lysates during the IP incubation. 2nd middle panel, equal expression of endogenous km23-1 protein was demonstrated by IP/blot analysis using the hkm23-1(1-15) as the IP Ab, and the hkm23-1(27-43)w as the blotting Ab. Bottom panel, the blots were scanned and quantified by using Image J software. The results are representative of triplicate experiments.

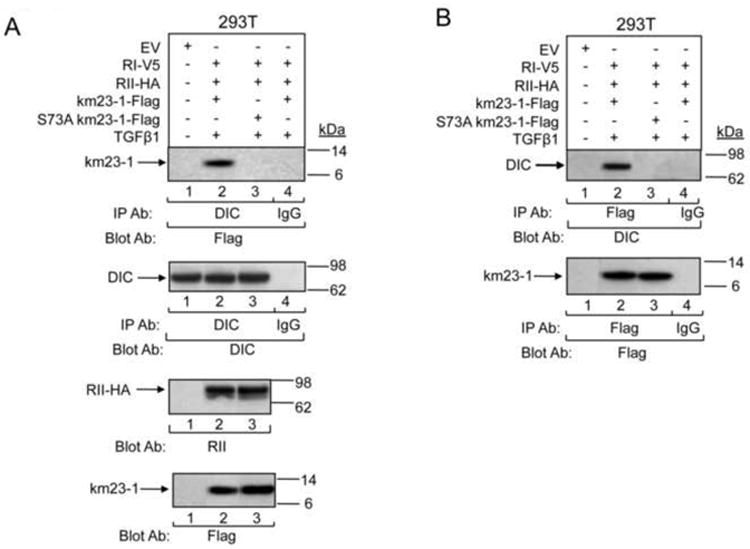

Our previous results (Tang et al., 2002) have shown that TGFß induces the interaction between km23-1 and the DIC subunit of the dynein motor complex over a time frame similar to that for TGFß induction of the PKA-Smad complex (Zhang et al., 2004). Further, disruption of the dynein complex inhibits TGFß induction of both nuclear translocation of Smad2 and Smad2-dependent transcriptional activation (Jin et al., 2007). These findings suggest that the km23-1-dynein complex is important for downstream TGFß/Smad2 signaling. Consequently, here we examined whether an S73A mutant of km23-1 would disrupt the km23-1 interaction with DIC. For these studies, we performed IP/blot analyses in 293T cells using anti-DIC as the IP antibody, and anti-Flag as the blotting antibody, after transient expression of either wt-km23-1 or S73A-km23-1 together with the TßRs. As shown in Fig. 4A, TGFß activation induced the recruitment of km23-1 to the DIC (lane 2), whereas the S73A-km23-1 mutant significantly blocked this interaction (lane 3). No specific bands were detectable in the EV (lane 1) and IgG (lane 4) control lanes. Other panels in Fig. 4A depict equal expression and loading for DIC, TßRII, and km23-1 proteins. In addition, performing IP/blot analyses in the opposite direction revealed the same disruption of the km23-1-dynein complex by the S73A-km23-1 mutant (Fig. 4B). Thus, our results suggest that the S73 site in km23-1 is important for downstream TGFß/Smad2 signaling.

Fig. 4. S73 is required for TGFß induction of the km23-1-DIC complex.

A: 293T cells were transiently co-transfected with the indicated plasmids. 24 h after transfection, cells were incubated in SF medium for 60 min before addition of TGFß1 (10 ng/ml) for 0, or 15 min. Cell lysates were then IP'd with an anti-DIC Ab and were then blotted with an anti-Flag Ab (top panel). The same membrane was then blotted with the DIC Ab to show equal IP'd proteins (1st middle panel). Equal inputs and expression of RII-HA, and Flag-tagged proteins were verified by Western blotting (bottom two panels). B: The IP/blot analysis using the samples from A was performed in the opposite direction with Flag as the IP Ab. Results are representative of two experiments.

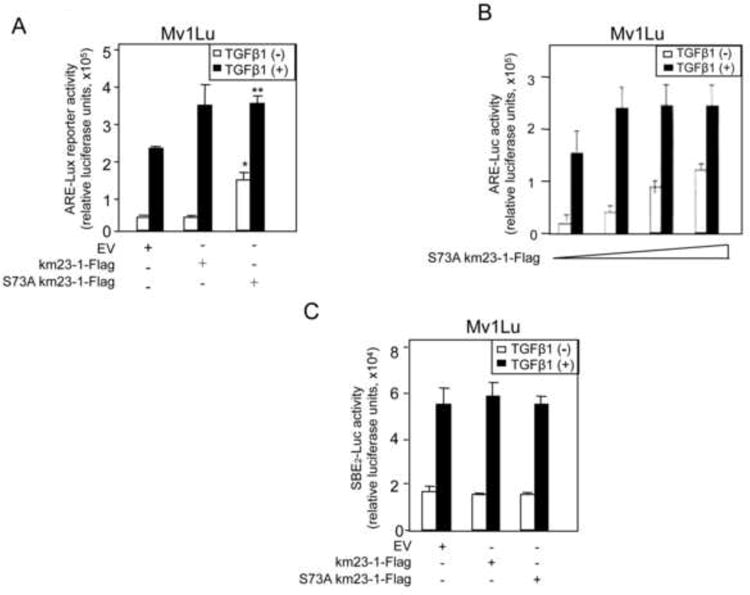

TGFß is known to activate the ARE-Lux reporter via complex formation of FAST-1 with Smad2 (Chen et al., 1997). Since we have previously shown that km23-1 knockdown reduced TGFß /Smad2 signaling (Jin et al., 2007), we tested the effect of the S73 mutant of km23-1 on Smad2-driven ARE-Lux reporter activity (Fig. 5A). km23-1, which by itself has no DNA binding or transactivation properties, did not significantly stimulate ARE-Lux beyond that detected for empty vector (EV). In contrast, the inactivating S73A mutant of km23-1 reduced the fold induction of ARE activity by TGFß. Interestingly, S73A-km23-1 also stimulated basal levels of ARE-Lux, and the increase was statistically significant (p<0.01). In order to more clearly define the effects of the S73A-km23-1 mutant on both basal and TGFß-stimulated ARE-lux, we expressed the S73A-km23-1-Flag at increasing concentrations. As shown in Fig. 5B, S73A-km23-1 displayed a dose-dependent decrease in the fold induction of ARE-Lux activity by TGFß with increasing doses of S73A-km23-1-Flag. Further, basal ARE-lux activity was increased in a dose-dependent manner. Our results demonstrate that phosphorylation on S73 of km23-1 is required for TGFß-dependent regulation of the ARE promoter. In contrast, inactivation of km23-1 phosphorylation at S73 stimulated ligand-independent ARE-lux activation. Our findings are consistent with the contention that S73A-km23-1 relieves an autoinhibitory effect on the ARE, suggesting that autocrine regulation of S73-km23-1 normally represses Smad2/FAST-1/ARE activity in the absence of exogenous TGFß.

Fig. 5. S73-km23-1 inhibits TGFß induction of TGFß/Smad2-dependent transcription in ARE reporter assays, but has no effect on TGFß/Smad3-dependent transcriptional activation.

A: Mv1Lu cells were transfected with EV, km23-1-Flag, or S73A km23-1-Flag, along with 0.2 μg of ARE-Lux reporter and 0.2 μg of FAST-1. To normalize transfection efficiencies, 0.2 μg of Renilla was co-transfected as an internal control. Luciferase reporter assays were performed as described in “Materials and Methods.” Error bars represent the SEM. The results are representative of at least two experiments, each performed in triplicate. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (p< 0.01) of the fold increase between the km23-1-Flag-transfected Mv1Lu cells and the EV-transfected in the absence of TGFß. Double asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (p< 0.01) in the fold changes for +/-TGFß between km23-1-Flag-transfected Mv1Lu cells and S73A km23-1-Flag-transfected Mv1Lu cells. B: Mv1Lu cells were transfected with increasing amounts of S73A km23-1-Flag, along with 0.2 μg of ARE-Lux reporter and 0.2 μg of FAST-1. C: Mv1Lu cells were transfected with either EV, km23-1, or S73A-km23-1, along with 0.2 μg of SBE2-Luc. The results are representative of three similar experiments, each performed in triplicate.

To determine whether S73A-km23-1 would also modulate TGFß/Smad3-dependent Smad binding element (SBE) promoter reporter activity, we performed similar luciferase reporter assays using the SBE2-Luc previously described (Jin et al., 2007; Zawel et al., 1998). In this regard, the SBE2-Luc reporter has been used previously to demonstrate Smad3/4-dependent responses induced by TGFß (Felici et al., 2003). As shown in Fig. 5C, S73A-km23-1 had no effect on TGFß-inducible SBE2-Luc. Thus, our results demonstrate that phosphorylation on S73 of km23-1 is specifically required for TGFß-dependent regulation of the Smad2-dependent ARE, but not for Smad3-dependent SBE reporter activity.

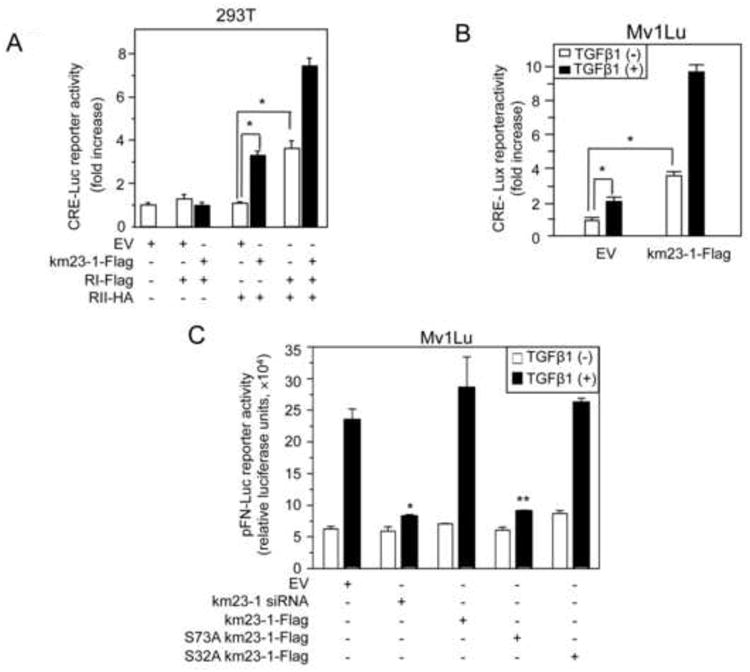

It is known that PKA activation is required for TGFß stimulation of fibronectin expression (Singh et al., 2004; Wang et al., 1998), and that blockade of km23-1 also significantly decreased induction of fibronectin expression (Jin et al., 2005). Therefore, it was of interest to investigate whether phosphorylation of S73-km23-1 by PKA modulates this key TGFß response. Fibronectin gene stimulation by TGFß is considered to be controlled, at least in part, by CRE sites located in the fibronectin promoter (Dean et al., 1988). Therefore, we first examined whether TGFß regulation of a CRE reporter would be affected by km23-1 over-expression in the absence or presence of TGFß. As shown in Fig. 6A, co-expression of RII-HA with km23-1 resulted in an increase in CRE-Luc luciferase activity (closed bars, 3rd set), relative to that observed after expression of EV alone (1st set), or after co-expression of RI-Flag with either EV or km23-1 (2nd set), or after co-expression of RII-HA with EV (open bars, 3rd set). Since co-expression of both TßRs is known to result in heteromeric complex formation and receptor activation in the absence of ligand (Ventura et al., 1994), as expected, expression of both I and TßRII without km23-1 stimulated CRE-Luc luciferase activity (open bars, 4th set). More significantly, co-expression of km23-1 with both TGFß receptors strongly enhanced CRE-Luc reporter activity in 293T cells (closed bars, 4th set). Thus, our results demonstrate that km23-1 is required for CRE transactivation, which is enhanced by TßR activation. Similarly, we performed CRE-Luc luciferase reporter assays after transiently transfecting Mv1Lu cells (having endogenous TßRs) with either EV or km23-1-Flag in the absence and presence of TGFß. As shown in Fig. 6B, over-expression of km23-1 resulted in a significant increase in trans-activation of the CRE-Luc in the absence and presence of TGFß. Thus, our results demonstrate that km23-1 can synergize with TßR activation and with TGFß to stimulate CRE luciferase reporter activity.

Fig. 6. km23-1 induces CRE transcriptional activation by TGFß, and S73-km23-1 is required for TGFß stimulation of CRE-dependent FN transcription.

A: 293T cells were transiently transfected with 0.2 μg CRE-Luc, 0.05 μg Renilla, and 0.1 μg of either RI-Flag, RII-HA and km23-1-Flag as indicated. 48h later, cells were lysed and the luciferase reporter assays were performed as described in “Materials and Methods.” Open bars, -km23-1-Flag; closed bars, +km23-1-Flag. The results are representative of triplicate experiments. *p<0.01. B: Mv1Lu cells were transfected with 0.4 μg of km23-1 or EV, 0.4 μg of CRE-Luc and 0.08 μg of Renilla. 21h later, cells were changed to SF conditions for 1h, followed by treatment with TGFß1 (10 ng/ml) for 24h. Luciferase reporter assays were performed as for A. The results are representative of triplicate experiments. *p<0.01. C: Mv1Lu cells were transfected with EV, km23-1 siRNA, km23-1, S32 km23-1-Flag or S73A-km23-1-Flag, along with 0.4 μg of pFN-Luc, 0.1 μg of Renilla. Luciferase reporter assays were performed as described in A. The results are representative of at least two experiments, each performed in triplicate. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (p< 0.001) of the fold changes between +/-TGFß for km23-1 siRNA-transfected Mv1Lu cells compared to EV-transfected Mv1Lu cells. Double asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (p< 0.001) of the fold changes comparing +/-TGFß between S73A km23-1-Flag-transfected Mv1Lu cells and EV-transfected Mv1Lu cells. The results are representative of at least two experiments, each performed in triplicate.

To further explore the functional significance of km23-1 in TGFß/PKA signaling downstream to FN, we performed pFN-Luc luciferase reporter assays after transient transfection with either S73 km23-1-Flag or the other indicated plasmids, along with the pFN-Luc reporter, in the absence or presence of TGFß. The pFN-Luc luciferase reporter has been described previously (Michaelson et al., 2002). As shown in Fig. 6C, TGFß induced pFN-Luc luciferase activity in the EV and km23-1 cells. In contrast, S73A-km23-1 resulted in a significant inhibition of TGFß induction of FN-Luc reporter activity, while S32A-km23-1 had no effect. As expected, siRNA depletion of km23-1 significantly decreased pFN-luc luciferase reporter activation. Thus, our results demonstrate that phosphorylation of km23-1 on S73 by PKA is required for TGFß induction of FN transcriptional activity, a major downstream response of both PKA and TGFß.

Discussion

In the current report, we demonstrate for the first time that PKA kinase activity was required for km23-1 functions involving the direct phosphorylation of S73-km23-1. This is consistent with predictions from NetPhos K whereby S73 is located within a PKA consensus site. The PKA and S73-km23-1 relationship was further characterized, and revealed that km23-1 and the PKA R1ß regulatory subunits are present in the same complex after TGFß treatment. The S73A mutant that could not be phosphorylated by PKA resulted in diminished TGFß-dependent regulation of both ARE and FN transcriptional activity. Collectively, our results demonstrate for the first time that phosphorylation of S73-km23-1 by PKA is required for activation of downstream TGFß signaling events.

Our findings also reveal a novel TGFß/PKA/km23-1/CRE effector pathway, mediated by km23-1 phosphorylation at S73, and leading to FN transcriptional activation. Along these lines, the mechanism(s) by which TGFß induces FN expression are still unclear. The FN promoter contains three CRE sites (Bowlus et al., 1991), one of which (CRE-170) has been shown to be occupied by c-Jun-ATF-2 (van Dam et al., 1993). It is also known that PKA activation is required for TGFß stimulation of FN gene expression, with both CREB and ATF-1 binding to the CRE site (Wang et al., 1998). Howe and co-workers (Hocevar et al., 1999; Hocevar et al., 2005) have reported that TGFß induction of FN expression requires the JNK pathway. We have shown that blockade of km23-1 significantly decreased induction of FN expression, demonstrating that km23-1 is also required for FN expression (Jin et al., 2005). Further, overexpression of km23-1 induced JNK activation (Tang et al., 2002), whereas km23-1 depletion reduced TGFß activation of JNK (Jin et al., 2012a). Altogether, the evidence suggests that the TGFß/km23-1 induction of FN also requires JNK activation.

In addition to the TGFß/PKA/km23-1/CRE pathway mediating FN induction, it is possible that the S73-P-km23-1 effects on Smad2/ARE contribute to FN induction. The FN promoter also contains an activator protein-2 (AP-2) consensus phosphorylation site (Kornblihtt et al., 1996). More recently, Smad2 has been shown to interact in a complex with AP-2 to regulate TGFß signaling activity (Koinuma et al, 2009). Further, CREB biding protein (P300/CBP), which is known to bind to Smad2 transcriptional complexes (Braganca et al., 2003; Janknecht et al., 1998), was shown to bind to AP-2 promoter regulatory sites to enhance transcription (Braganca et al., 2003). Since FN represents one of these AP-2-regulated genes, the S73-P-km23-1 regulation of Smad2/ARE may ultimately activate transcription from the AP-2 site in the FN promoter, mediated by AP-2/Smad2/p300CBP complexes. According to this model, PKA phosphorylation of km23-1 would permit cross-talk between the JNK/Jun/CRE and Smad2/ARE/AP-2 effector pathways, providing tight control of FN transcription. Along these lines, TGFß/Smad2-dependent regulation of FN has been reported for other cell types, although the mechanism was not elucidated (Lai et al., 2006).

Our results also show that PKA phosphorylation of km23-1 on S73 was detectable at 30 min after TGFß addition, at a time when the PKA R1ß regulatory subunit starts to dissociate from km23-1. This is in keeping with previous reports showing that PKA is activated by TGFß as soon as 15 min after TGFß treatment, often regulated by a Smad3/4 complex (Wang et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2004). Thereafter, the PKA catalytic subunits may be released from the holoenzyme and move into nucleus to regulate gene transcription (Wang et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2004). With regard to Smad signaling, here we show that S73-km23-1 is required for TGFß/Smad2 transcriptional events, but not for TGFß/Smad3 SBE transactivation. This is in contrast to previous reports, which implicate Smad3, but not Smad2, as a major component of the TGFß-stimulated complex with the regulatory subunit of PKA (Chowdhury et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2004). In addition, the PKA/S73-P-km23-1 regulation of Smad2/ARE transcription observed here (Fig. 5A) likely occurs downstream from the TGFß-regulated TßRII-km23-1-Smad2 complex that we have previously described (Jin et al., 2007). Moreover, the finding that the S73A-km23-1 mutant inhibited the km23-1-dynein complex, which is important for subsequent Smad2 nuclear translocation, suggests that the PKA phosphorylation of km23-1 at S73 occurs prior to TGFß-mediated nuclear translocation of Smad2. Consequently, our findings support a role for km23-1 at multiple levels in the regulation of these critical signaling complexes, further demonstrating the importance of unraveling each of the unique steps at which km23-1 can function.

While this is the first report of a positive regulatory role for PKA in km23-1-dependent TGFß signaling, several studies regarding PKA have revealed roles for this kinase in TGFß signaling. A bioinformatics study identified a TßR binding domain in the sequence for a specific adaptor protein of PKA, one of the A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs). It was suggested that the PKA holoenzyme is probably targeted to an AKAP complex, which includes the hetero-tetramer of TßRs (Herrgard et al., 2000). Another study has suggested that AKAPs are required for the subcellular localization of PKA and for its interaction with Smads (Zhang et al., 2004). A more recent study demonstrated that the specific AKAP149 is a novel TGFß/PKA signaling transduceome, which has a critical role in TGFß-mediated PKA activation (Chowdhury et al., 2011). Here we have found that PKA phosphorylation of S73-km23-1 can regulate both TGFß-dependent and independent events, further illustrating the importance of this signaling intermediate in modulating cell phenotype. Along these lines, we have recently shown that km23-1 plays a critical role in RhoA/actin-based cell migration (Jin et al., 2012b). Since PKA is known to regulate RhoA (Tkachenko et al., 2011), future studies will address the mechanisms linking km23-1's effects on these critical components.

In summary, here we show that km23-1 interacts with the R1ß regulatory subunit of PKA. It is phosphorylated both in vitro and in vivo by PKA at S73, with the S73A-km23-1 mutant resulting in a significant inhibition of TGFß induction of FN transcriptional activity. In addition, km23-1 can synergize with the TGFß receptor complex and with TGFß to stimulate CRE-Lux luciferase reporter activity. Collectively, our results demonstrate that phosphorylation of km23-1 on S73 by PKA is required for TGFß induction of FN transcription, which is a CRE-mediated physiological response of both PKA and TGFß. In addition, the S73 phosphorylation site in km23-1 regulates Smad2/ARE activity, which may also play a role in induction of FN expression. Overall, it is likely that km23-1 functions as a novel mediator of signaling cross-talk between the PKA, JNK/Jun/CRE, and Smad2 pathways in the induction of FN by TGFß.

Highlights.

km23-1 is phosphorylated by PKA at serine 73 both in vitro and in vivo

TGFß regulates km23-1 interaction with the R1ß regulatory subunit of PKA

km23-1 synergizes with the TGFß ligand-receptor complex to stimulate the CRE

PKA phosphorylation of km23-1 is required for TGFß induction of FN transcription

km23-1 mediates signaling cross-talk between PKA, JNK/ CRE, and Smad2 pathways

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Scott E. Kern (Johns Hopkins Oncology Center, Baltimore, MD) for SBE2-Luc, and Dr. Malcolm Whitman (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) for the ARE-Lux and FAST-1. We also thank Dr. Kohei Miyazono (University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan) for the V5-tagged RI construct, and Dr. Jeffrey L. Wrana (Samuel Lunenfeld Res. Institute, Toronto, Canada for the HA-tagged RII construct).

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health to K. M. M.

Grant Numbers: CA090765, CA092889 and CA092889-08S1

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: The authors have no conflicts of interests to declare with the work presented herein.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashokkumar B, Nabokina SM, Ma TY, Said HM. Identification of dynein light chain road block-1 as a novel interaction partner with the human reduced folate carrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;297(3):G480–487. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00154.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom N, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Gupta R, Gammeltoft S, Brunak S. Prediction of post-translational glycosylation and phosphorylation of proteins from the amino acid sequence. Proteomics. 2004;4(6):1633–1649. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlus CL, McQuillan JJ, Dean DC. Characterization of three different elements in the 5′-flanking region of the fibronectin gene which mediate a transcriptional response to cAMP. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(2):1122–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braganca J, Eloranta JJ, Bamforth SD, Ibbitt JC, Hurst HC, Bhattacharya S. Physical and functional interactions among AP-2 transcription factors, p300/CREB-binding protein, and CITED2. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(18):16021–16029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208144200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell IG, Phillips WA, Choong DY. Genetic and epigenetic analysis of the putative tumor suppressor km23 in primary ovarian, breast, and colorectal cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(12):3713–3715. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Weisberg E, Fridmacher V, Watanabe M, Naco G, Whitman M. Smad4 and FAST-1 in the assembly of activin-responsive factor. Nature. 1997;389(6646):85–89. doi: 10.1038/38008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S, Howell GM, Rajput A, Teggart CA, Brattain LE, Weber HR, Chowdhury A, Brattain MG. Identification of a novel TGFbeta/PKA signaling transduceome in mediating control of cell survival and metastasis in colon cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couwenbergs C, Labbe JC, Goulding M, Marty T, Bowerman B, Gotta M. Heterotrimeric G protein signaling functions with dynein to promote spindle positioning in C. elegans. J Cell Biol. 2007;179(1):15–22. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200707085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean DC, Newby RF, Bourgeois S. Regulation of fibronectin biosynthesis by dexamethasone, transforming growth factor beta, and cAMP in human cell lines. J Cell Biol. 1988;106(6):2159–2170. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.6.2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felici A, Wurthner JU, Parks WT, Giam LR, Reiss M, Karpova TS, McNally JG, Roberts AB. TLP, a novel modulator of TGF-beta signaling, has opposite effects on Smad2- and Smad3-dependent signaling. Embo J. 2003;22(17):4465–4477. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J, Song Y, Karplus PA, Barbar E. The crystal structure of dynein intermediate chain-light chain roadblock complex gives new insights into dynein assembly. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(29):22566–22575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.103861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrgard S, Jambeck P, Taylor SS, Subramaniam S. Domain architecture of a Caenorhabditis elegans AKAP suggests a novel AKAP function. FEBS Lett. 2000;486(2):107–111. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocevar BA, Brown TL, Howe PH. TGF-beta induces fibronectin synthesis through a c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent, Smad4-independent pathway. Embo J. 1999;18(5):1345–1356. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocevar BA, Prunier C, Howe PH. Disabled-2 (Dab2) mediates transforming growth factor beta (TGFbeta)-stimulated fibronectin synthesis through TGFbeta-activated kinase 1 and activation of the JNK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(27):25920–25927. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501150200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe AK. Cross-talk between calcium and protein kinase A in the regulation of cell migration. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23(5):554–561. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilangovan U, Ding W, Zhong Y, Wilson CL, Groppe JC, Trbovich JT, Zuniga J, Demeler B, Tang Q, Gao G, Mulder KM, Hinck AP. Structure and dynamics of the homodimeric dynein light chain km23. J Mol Biol. 2005;352(2):338–354. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janknecht R, Wells NJ, Hunter T. TGF-beta-stimulated cooperation of smad proteins with the coactivators CBP/p300. Genes Dev. 1998;12(14):2114–2119. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Yu L, Huang X, Chen X, Li D, Zhang Y, Tang L, Zhao S. Identification of two novel human dynein light chain genes, DNLC2A and DNLC2B, and their expression changes in hepatocellular carcinoma tissues from 68 Chinese patients. Gene. 2001;281(1-2):103–113. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00787-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q, Ding W, Mulder KM. Requirement for the dynein light chain km23-1 in a Smad2-dependent transforming growth factor-beta signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(26):19122–19132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609915200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q, Ding W, Mulder KM. The TGFbeta Receptor-interacting Protein km23-1/DYNLRB1 Plays an Adaptor Role in TGFbeta1 Autoinduction via Its Association with Ras. J Biol Chem. 2012a;287(31):26453–26463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.344887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q, Ding W, Staub CM, Gao G, Tang Q, Mulder KM. Requirement of km23 for TGFbeta-mediated growth inhibition and induction of fibronectin expression. Cell Signal. 2005;17(11):1363–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q, Gao G, Mulder KM. Requirement of a dynein light chain in TGFbeta/Smad3 signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2009;221(3):707–715. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Q, Pulipati NR, Zhou W, Staub CM, Liotta LA, Mulder KM. Role of km23-1 in RhoA/actin-based cell migration. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012b doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.10.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HC, Kim IJ, Kim K, Yoon HJ, Jang SG, Park JG. km23, a transforming growth factor-beta signaling component, is infrequently mutated in human colorectal and gastric cancers. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2007;175(2):173–174. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JS, Liu C, Derynck R. New regulatory mechanisms of TGF-beta receptor function. Trends Cell Biol. 2009;19(8):385–394. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornblihtt AR, Pesce CG, Alonso CR, Cramer P, Srebrow A, Werbajh S, Muro AF. The fibronectin gene as a model for splicing and transcription studies. Faseb J. 1996;10(2):248–257. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.2.8641558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotani T. Protein kinase A activity and Hedgehog signaling pathway. Vitam Horm. 2012;88:273–291. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394622-5.00012-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L, Chen J, Hao CM, Lin S, Gu Y. Aldosterone promotes fibronectin production through a Smad2-dependent TGF-beta1 pathway in mesangial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;348(1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maymo JL, Perez Perez A, Maskin B, Duenas JL, Calvo JC, Sanchez Margalet V, Varone CL. The Alternative Epac/cAMP Pathway and the MAPK Pathway Mediate hCG Induction of Leptin in Placental Cells. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e46216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaelson JE, Ritzenthaler JD, Roman J. Regulation of serum-induced fibronectin expression by protein kinases, cytoskeletal integrity, and CREB. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282(2):L291–301. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00445.2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu Y, Gudey SK, Landstrom M. Non-Smad signaling pathways. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347(1):11–20. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder KM. Role of Ras and Mapks in TGFbeta signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2000;11(1-2):23–35. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00026-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikulina K, Patel-King RS, Takebe S, Pfister KK, King SM. The Roadblock light chains are ubiquitous components of cytoplasmic dynein that form homo- and heterodimers. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2004;57(4):233–245. doi: 10.1002/cm.10172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padua D, Massague J. Roles of TGFbeta in metastasis. Cell Res. 2009;19(1):89–102. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park MH, Lee HS, Lee CS, You ST, Kim DJ, Park BH, Kang MJ, Heo WD, Shin EY, Schwartz MA, Kim EG. p21-Activated kinase 4 promotes prostate cancer progression through CREB. Oncogene. 2012:1–8. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfister KK, Fisher EM, Gibbons IR, Hays TS, Holzbaur EL, McIntosh JR, Porter ME, Schroer TA, Vaughan KT, Witman GB, King SM, Vallee RB. Cytoplasmic dynein nomenclature. J Cell Biol. 2005;171(3):411–413. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piek E, Ju WJ, Heyer J, Escalante-Alcalde D, Stewart CL, Weinstein M, Deng C, Kucherlapati R, Bottinger EP, Roberts AB. Functional characterization of transforming growth factor beta signaling in Smad2- and Smad3-deficient fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(23):19945–19953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102382200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh LP, Green K, Alexander M, Bassly S, Crook ED. Hexosamines and TGF-beta1 use similar signaling pathways to mediate matrix protein synthesis in mesangial cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286(2):F409–416. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00007.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susalka SJ, Nikulina K, Salata MW, Vaughan PS, King SM, Vaughan KT, Pfister KK. The roadblock light chain binds a novel region of the cytoplasmic Dynein intermediate chain. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(36):32939–32946. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205510200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q, Staub CM, Gao G, Jin Q, Wang Z, Ding W, Aurigemma RE, Mulder KM. A novel transforming growth factor-beta receptor-interacting protein that is also a light chain of the motor protein dynein. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(12):4484–4496. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-05-0245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SS, Buechler JA, Yonemoto W. cAMP-dependent protein kinase: framework for a diverse family of regulatory enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:971–1005. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.004543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tkachenko E, Sabouri-Ghomi M, Pertz O, Kim C, Gutierrez E, Machacek M, Groisman A, Danuser G, Ginsberg MH. Protein kinase A governs a RhoA-RhoGDI protrusion-retraction pacemaker in migrating cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(6):660–667. doi: 10.1038/ncb2231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dam H, Duyndam M, Rottier R, Bosch A, de Vries-Smits L, Herrlich P, Zantema A, Angel P, van der Eb AJ. Heterodimer formation of cJun and ATF-2 is responsible for induction of c-jun by the 243 amino acid adenovirus E1A protein. Embo J. 1993;12(2):479–487. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05680.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura F, Doody J, Liu F, Wrana JL, Massague J. Reconstitution and transphosphorylation of TGF-beta receptor complexes. Embo J. 1994;13(23):5581–5589. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06895.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DA, Van Patten SM. Multiple pathway signal transduction by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. Faseb J. 1994;8(15):1227–1236. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.15.8001734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhu Y, Sharma K. Transforming growth factor-beta1 stimulates protein kinase A in mesangial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(14):8522–8527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.14.8522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanschers B, van de Vorstenbosch R, Wijers M, Wieringa B, King SM, Fransen J. Rab6 family proteins interact with the dynein light chain protein DYNLRB1. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2008;65(3):183–196. doi: 10.1002/cm.20254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Lee CJ, Zhang L, Sans MD, Simeone DM. Regulation of transforming growth factor beta-induced responses by protein kinase A in pancreatic acinar cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;295(1):G170–G178. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00492.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo CY, Chen X, Whitman M. The role of FAST-1 and Smads in transcriptional regulation by activin during early Xenopus embryogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(37):26584–26590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yue J, Mulder KM. Transforming growth factor-beta signal transduction in epithelial cells. Pharmacol Ther. 2001;91(1):1–34. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(01)00143-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zawel L, Dai JL, Buckhaults P, Zhou S, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Kern SE. Human Smad3 and Smad4 are sequence-specific transcription activators. Mol Cell. 1998;1(4):611–617. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Duan CJ, Binkley C, Li G, Uhler MD, Logsdon CD, Simeone DM. A transforming growth factor beta-induced Smad3/Smad4 complex directly activates protein kinase A. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(5):2169–2180. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.5.2169-2180.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Smith-Nguyen EV, Keshwani MM, Deal MS, Kornev AP, Taylor SS. Structure and allostery of the PKA RIIbeta tetrameric holoenzyme. Science. 2012;335(6069):712–716. doi: 10.1126/science.1213979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YE. Non-Smad pathways in TGF-beta signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19(1):128–139. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]