Abstract

Although nearly half of today’s major pharmaceutical drugs target human integral membrane proteins (hIMPs), only 30 hIMP structures are currently available in the Protein Data Bank, largely owing to inefficiencies in protein production. Here we describe a strategy for the rapid structure determination of hIMPs, using solution NMR spectroscopy with systematically labeled proteins produced via cell-free expression. We report new backbone structures of six hIMPs, solved in only 18 months from 15 initial targets. Application of our protocols to an additional 135 hIMPs with molecular weight <30 kDa yielded 38 hIMPs suitable for structural characterization by solution NMR spectroscopy without additional optimization.

About 30% of the human protein-coding genes encode IMPs, which have critical roles in metabolism, regulation, transport and intercellular signaling. hIMPs are the targets of 50% of approved therapeutic drugs; however, difficulties with the manipulation of hIMPs have impeded the detailed functional and structural studies required to expedite drug development and discovery. These difficulties are associated with hIMP expression, purification, crystallization for X-ray structural studies, and isotopic labeling and resonance assignment for solution NMR spectroscopy studies. Notably, cellular prokaryotic expression systems generally lack compatible translocation machineries for hIMPs, and eukaryotic systems are expensive and difficult to handle. Consequently, only 30 structures of hIMPs are currently deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

Recently, Escherichia coli–derived cell-free expression systems have proven effective in overcoming many limitations inherent to in vivo expression in prokaryotic hosts1. In the absence of compartmentalization in a hydrophobic milieu, IMPs produced in a cell-free expression system form precipitates that can be subsequently solubilized in mild detergents. We named this mode of expression precipitating cell-free (P-CF) expression1. Alternatively, inclusion of a detergent or a lipid can effect direct expression of solubilized IMPs2–5. We have extensively optimized P-CF expression for IMP production and had demonstrated efficient production of natively folded protein6. Other studies have also shown cell-free expression of fully functional G protein– coupled receptors and transporters7–11.

Transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy (TROSY)-based experiments have expanded the applicability of three-dimensional (3D) structure determination by solution NMR spectroscopy to large systems12, including micelle-bound membrane proteins13–17. The tremendous adaptability of cell-free expression makes it ideally suited to the isotopic labeling strategies used for these experiments. In particular, the cell-free combinatorial dual-labeling (CDL) strategy6 has greatly facilitated the usually laborious sequential assignment of IMP resonances. Furthermore, technological limitations in the acquisition of the requisite long-range distance constraints for 3D structure determination have been overcome thanks to the measurements of paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) caused by an exogenous or covalently bound paramagnetic group18–21 and the measurements of long-range nuclear Overhauser effects (NOE) for deuterated and selectively protonated proteins22 solubilized in deuterated detergents. Here we describe an application of a highly effective and fast strategy, which combines NMR spectroscopy and cell-free expression, to determine the structure of six hIMPs.

RESULTS

Expression screening and NMR spectroscopy

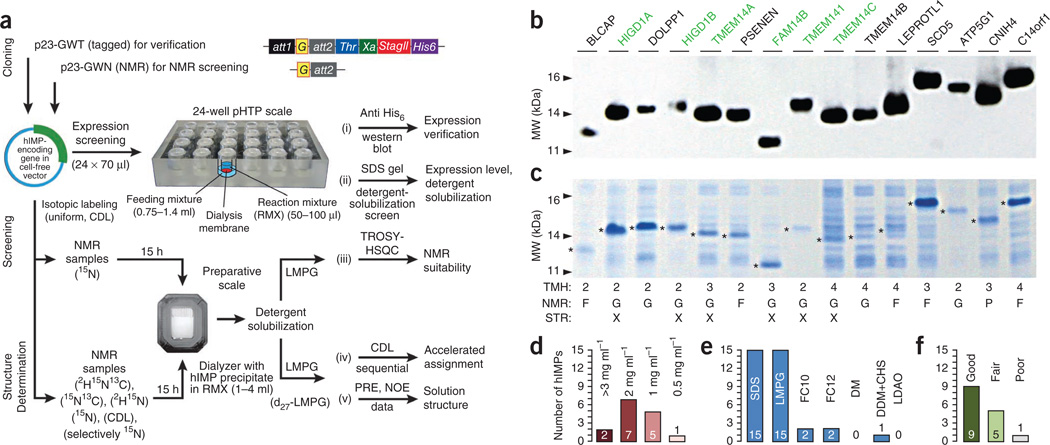

We surveyed the hIMP proteome for favorable targets for solution NMR spectroscopy structural studies (Fig. 1a) and initially selected 15 moderately sized (<20 kDa), polytopic (two or more membrane crossings) hIMPs (Fig. 1b–f). We expressed all but one of these in our E. coli–derived P-CF system at high levels (>1 mg per 1 ml of reaction mixture) (Fig. 1c,d). The proteins were suitable for subsequent characterizations without additional purification. The lipid-derived detergent 1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)] (LMPG) was the most effective of the seven detergents screened for solubilizing the protein precipitates produced by P-CF expression (Fig. 1e). We measured [1H-15N]TROSY–heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra from the solubilized, uniformly 15N-labeled hIMPs and evaluated their quality (good, fair or poor; Fig. 1c,f) according to the number of visible glycine backbone and tryptophan indole H-N resonances, the total number of cross-peaks, the chemical shift dispersion and the uniformity of line shapes.

Figure 1.

Workflow for screening and evaluation of 15 selected hIMPs for structural studies. (a) hIMP genes (G) are cloned into suitable Gateway-adapted cell-free vectors (Online Methods). P-CF expression is screened using a 24-well preparative high-throughput (pHTP) setup, followed by verification of expression, efficiency of detergent solubilization and suitability for NMR spectroscopy. Structure determination involves P-CF expression of uniformly or selectively labeled sample, protein solubilization, assignment using CDL and standard approaches, and collection of PRE and NOE data for structure calculation. (b,c) Western blot (b) and Coomassie stain gel (c) of indicated proteins (hIMPs with determined structures are labeled in green). TMH, numbers of predicted transmembrane helices; NMR, NMR spectral quality information labeled as good (G), fair (F) or poor (P); structure, 'X' marks hIMPs with determined solution structure. Asterisks indicate the position of expressed proteins. (d–f) Summary of evaluation for the 15 proteins. Expression of all 15 proteins was verified by western blot. Number of proteins classified according to cell-free expression levels (d). Number of proteins solubilized with each of the tested detergents: 70 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 42 mM 1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)] (LMPG), 100 mM n-decylphosphocholine (FC10), 100 mM n-dodecylphosphocholine (FC12), 250 mM n-decyl-β-d-maltoside (DM), mixture of 196 mM n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM) with 41 mM cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS) and 100 mM lauryldimethylamine-N-oxide (LDAO) (e). Number of proteins classified according to NMR spectral quality (f).

Characterization and NMR signal assignment of six hIMPs

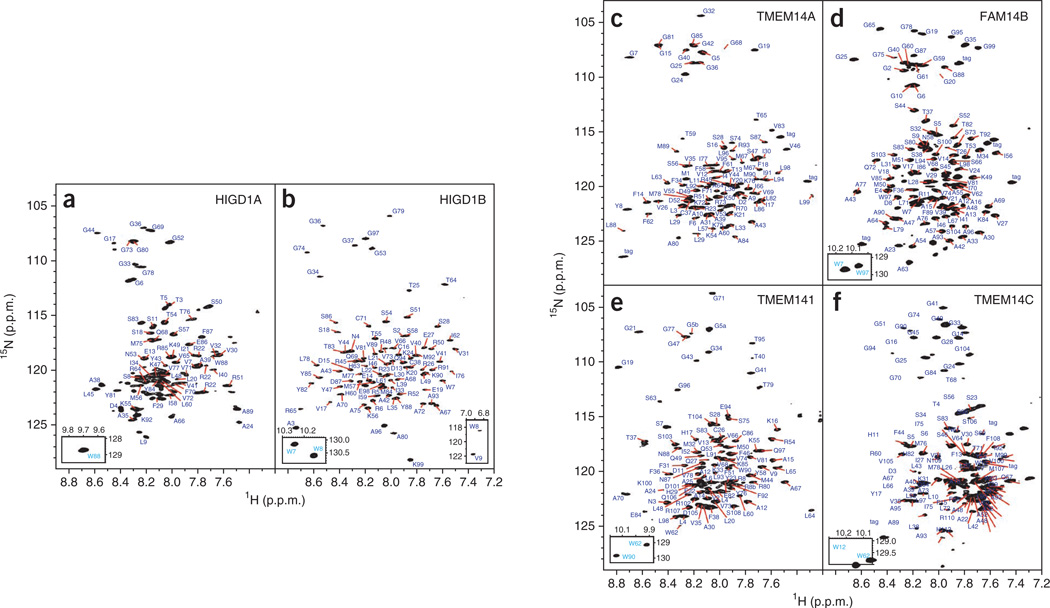

From our initial 15 hIMP preparations, nine produced good [1H-15N]TROSY-HSQC spectra and were suited for comprehensive NMR spectroscopy studies. For six of these nine hIMPs, we assigned resonances (Fig. 2) using the CDL strategy6 (Supplementary Table 1) and conventional sequential assignment. The percentages of resonances assigned for backbone and side-chain atoms for the six proteins are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Static light scattering coupled with size-exclusion gel chromatography and refracting index measurements revealed that these hIMPs were monomeric in LMPG micelles (Supplementary Fig. 1). We verified that H1GD1B was also monomeric in three different detergents: LMPG, dodecylphosphocholine (FC12) and n-dodecyl beta-maltoside (DDM) (Supplementary Fig. 2). We also verified that proteins were micelle-embedded and determined the regions of the target proteins embedded into the LMPG micelle by analyzing the PRE effect caused by the hydrophilic spin-labeled probe (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

NMR spectral quality and N-H backbone assignment for six hIMPs. (a–f) [1H,15N]TROSY-HSQC spectra with assignment of NH cross-peaks for six hIMPs (Online Methods). Insets, tryptophan indole NH cross-peaks (bottom left), and high-field shifted backbone NH cross-peaks (bottom right).

NMR spectroscopy structure determination of hIMPs

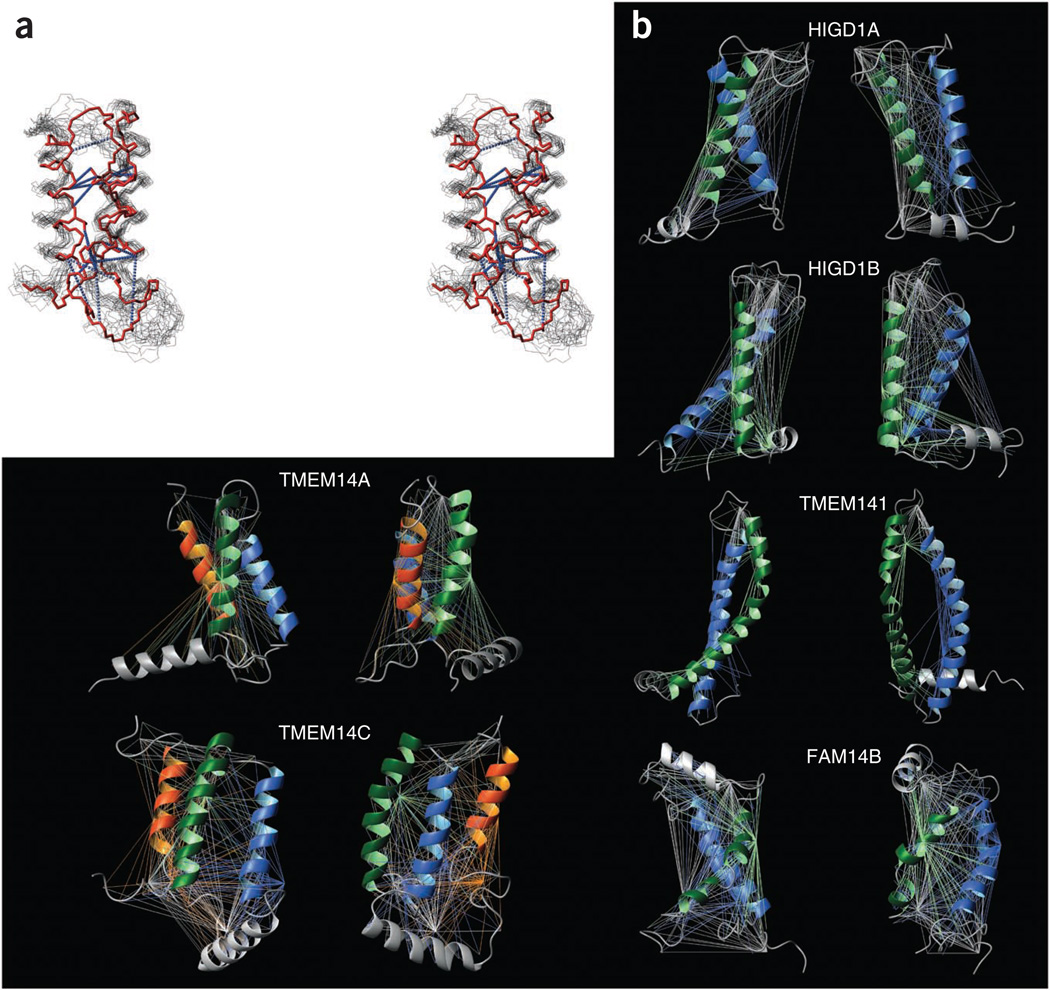

We used the chemical shift index calculated for 13Cα, 13Cβ and 13CO atoms to localize the helical regions of the proteins. We calculated backbone structures of the six hIMPs based on long-range distance constraints obtained from PRE measurements of the spin-labeled proteins using single cysteine mutants (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5 and Supplementary Table 3). To validate the PRE-based structure calculations, we calculated the spatial structure of TMEM14A using PRE and independently using long-range distance constraints obtained from NOEs. The structures were similar, with average r.m.s. deviation between the backbone atoms of the transmembrane helical regions in the PRE- and NOE-based structures equal to 3.05 Å (Fig. 3a). The NOE-based structure of TMEM14A comprised a more tightly packed helical bundle than the PRE-based structure, whereas the orientation and topology of the transmembrane helices were very similar. The reason for the less tight packing of the bundle in the PRE-based structure lies in the impossibility of calculating short (<12 Å) PRE constraints using nitroxide paramagnetic spin label and in the lower precision of this type of constraints as compared to NOE-based constraints (Online Methods). To determine whether the helical orientation can be unambiguously determined from the PRE data, we calculated the PRE constraints error for generic structures with transmembrane helices rotated around the helical axes. The structures with the low cumulative error function (smaller than 1 Å2) calculated for PRE constraints were located within a 20° rotation range from the starting structure (angles 0, 0) (Supplementary Fig. 6). PRE distances quality factor did not exceed 13.6% among the calculated hIMP structures (Table 1), which shows good agreement between PRE-derived distances used in structure calculation and distances back-calculated from the structures. NMR spectroscopy experimental data, including structural and refinement statistics for the calculated structures, are summarized in Table 1. The long-range distance constraints used for structure calculation are illustrated in Figure 3b.

Figure 3.

Solution NMR spectroscopy structures and long-distance constraints used in structure calculations. (a) Stereo view of the TMEM14A structures calculated using separate sets of NOE- and PRE-based long-range distance constraints. The best structure calculated using NOE constraints (red) was superimposed with the best 20 structures calculated using PRE-based constraints (black). Long-range NOE constraints are shown with blue dotted lines between heavy atoms (instead of attached protons) for clarity of the figure. The structures are superimposed by backbone atoms of transmembrane helical regions. The backbone of the region Gly24–Leu98 is shown. Side chains with the long-range NOE contacts are also shown for NOE-based structure. (b) Ribbon representation of solution NMR spectroscopy structures of six hIMPs and long-distance constraints used in structure calculation. The long-range distance constraints obtained from PREs measurements are indicated by straight lines colored according to the color of the spin-labeled transmembrane helix (first is colored in green, second in blue and third in orange). Additional non-transmembrane helices and PRE constraints obtained with the spin labels located outside the transmembrane regions are colored in gray. The structures are shown in pairs with 90° vertical rotation.

Table 1.

Summary of NMR spectroscopy data and statistics for the calculated sets of 20 lowest-energy structures

| TMEM14A |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIGD1A | HIGD1B | NOE | PRE | FAM14B | TMEM141 | TMEM14c | |

| Protein size (amino acids) | 93 | 99 | 99 | 104 | 108 | 112 | |

| Transmembrane segments (predicteda) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 3 (3) | 2 (3) | 2 (2) | 3 (4) | |

| Global rotational correlation timeb (ns) | 25.1 | 28.8 | 25.5 | 21.6 | 20.7 | 25.5 | |

| Cysteine mutants | 6 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 9 | |

| NMR constraints | |||||||

| NOE (long-range NOEd) | 40c | 47c | 651 (18d) | 0 | 49c | 153 | 55c |

| PRE: upper/lower | 156/186 | 224/240 | 0 | 334/467 | 195/389 | 162/235 | 283/479 |

| Number of PRE per restrained residue: upper/total restrained distances | 3.63/5.23 | 4.07/6.34 | 0 | 4.64/7.38 | 3.98/8.39 | 1.80/2.61 | 4.56/8.76 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 41 | 44 | 44 | 44 | 51 | 60 | 58 |

| Dihedral angle: Phi/Psi | 43/43 | 53/55 | 72/72 | 72/72 | 45/49 | 86/90 | 62/61 |

| Structure statisticse | |||||||

| Violations (mean ± s.d.) | |||||||

| Distance, sum (Å) | 2.80 ± 0.10 | 1.35 ± 0.11 | 2.53 ± 0.39 | 2.42 ± 0.18 | 3.11 ± 0.16 | 1.15 ± 0.07 | 3.29 ± 0.36 |

| Distance, average (Å) | 0.19 ± 0.03 | 0.17 ± 0.04 | 0.15 ± 0.06 | 0.13 ± 0.06 | 0.26 ± 0.14 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.21 ± 0.06 |

| Maximum distance violation (Å) | 0.24 ± 0.01 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 0.31 ± 0.04 |

| Dihedral angle, sum (°) | 1.36 ± 0.55 | 1.02 ± 0.67 | 3.78 ± 1.24 | 2.11 ± 0.60 | 4.87 ± 0.72 | 3.73 ± 1.37 | 4.78 ± 1.39 |

| Maximum dihedral angle violation (°) | 0.56 ± 0.13 | 0.51 ± 0.30 | 0.90 ± 0.29 | 0.84 ± 0.32 | 0.75 ± 0.19 | 0.48 ± 0.10 | 0.73 ± 0.21 |

| PRE distances Q-factor (%) | 12.3 | 13.4 | NA | 12.1 | 13.6 | NA | 13.1 |

| Average backbone r.m.s. deviation (Å) | 1.52 ± 0.59 | 0.73 ± 0.19 | 1.72 ± 0.65 | 1.82 ± 0.48 | 1.11 ± 0.42 | 3.52 ± 1.51 | 1.42 ± 0.37 |

| Ramachandran plot statisticse,f | |||||||

| Most favored regions (%) | 71.6 | 67.3 | 73.0 | 70.6 | 70.7 | 80.9 | 71.9 |

| Additionally/generously allowed (%) | 19.6/6.2 | 23.1/7.1 | 17.6/7.1 | 22.4/4.9 | 21.9/4.8 | 15.2/2.8 | 17.8/7.2 |

| Disallowed (%) | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 1.1 | 3.1 |

| Deviations from idealized geometryg | |||||||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.013 | 0.010 | 0.012 | 0.013 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| Equivalent resolutionf,g (Å) | 3.3 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.0 | 3.1 |

Number of predicted transmembrane helices is given in parentheses.

Calculated for total mass of protein-detergent complex using the Stokes-Einstein equation.

Inter-residue sequential (|i – j| = 1) constraints only.

Number of long-range (|i – j| > 4) NOE constraints is given in parentheses.

Calculated for transmembrane bundles.

Calculated by Procheck program31.

Based on Ramachandran plot quality assessment.

NA, not applicable.

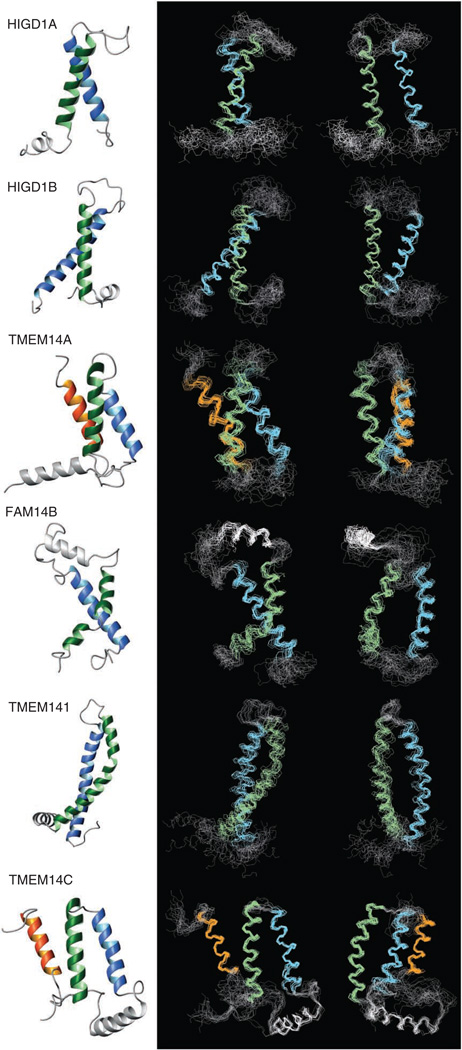

NMR spectroscopy structures of six hIMPs

All six hIMP structures were helical bundles with helix lengths and exposed hydrophobic faces consistent with the bilayer-embedded localization of these proteins (Fig. 4). In agreement with the numbers of predicted transmembrane helices (Fig. 1c), HIGD1A, HIGD1B and TMEM141 had two transmembrane crossings, whereas TMEM14A had three transmembrane crossings. compared to the prediction of three and four transmembrane helices, FAM14B and TMEM14C had two and three transmembrane crossings, respectively (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 7). The first transmembrane helix of both FAM14B and TMEM141 was severely kinked (by about 50°; Supplementary Table 4). For HIGD1A, HIGD1B, TMEM141 and TMEM14A, the first transmembrane helix was preceded by an amphiphilic N-terminal helix; this helix is presumably located at the micelle-water interface, but we could not define its exact orientation relative to the transmembrane helical bundles. The connecting loops between the transmembrane helices of FAM14B and second and third transmembrane helices of TMEM14C contain an amphiphilic helix, which lies roughly perpendicular to the preceding transmembrane helix. As a moderate PRE effect caused by the soluble paramagnetic agent was detected for backbone amides of the amphiphilic helices (Supplementary Fig. 3), we can assume that the helices are located close to the surface of the LMPG micelle. TMEM141 has remarkably elongated transmembrane helices of 34 and 33 amino acids. The N-terminal part of the first transmembrane helix and C-terminal part of the second one protruded from the micelle as confirmed by a moderate PRE effect from the soluble paramagnetic agent (Supplementary Fig. 3d). The three-helical bundles of TMEM14A and TMEM14C were tightly packed with interhelical distances less than 8 Å, whereas the two-helical bundles of HIGD1A, HIGD1B, FAM14B and TMEM141 were more loosely packed with interhelical distances exceeding 8 Å and relatively few interhelical van der Waals contacts localized close to the ends of the helices. The parameters describing packing of the helices (pair-wise angles between the transmembrane helices and bending angles of the transmembrane helices) are listed in Supplementary Table 4. The backbone structures of HIGD1A, HIGD1B, FAM14B, TMEM141, TMEM14A and TMEM14C reported here account for 20% of hIMP entries currently in PDB.

Figure 4.

Solution NMR spectroscopy structures of six hIMPs. Structures were calculated by Cyana using distance information obtained from NOE and PRE measurements. The first transmembrane helix is in green, second in blue and third in orange. Additional non-transmembrane helices are in gray. Shown are ribbon structures (left), superposition of the best 20 backbone structures (middle) and their 90° vertical rotation (right).

The structures of these proteins could immediately serve as a model for a substantial portion of the membrane proteome. A search of the UniProtKB database of all known protein sequences identified 609 unique protein sequences with sequence identity greater than 30% to at least one of the six hIMPs. Based on the determined structures, we calculated structural models for these 609 unique protein sequences. Additional lower accuracy structural information is provided for additional 380 protein sequences at sequence identities below 30% (Supplementary Table 5).

hIMP-specific antibody generation by a P-CF product

We demonstrated that the P-CF–expressed hIMP elicit the production of highly specific polyclonal antibodies. A rabbit polyclonal antibody (Eton Bioscience) was generated to P-CF–expressed and detergent-solubilized HIGD1A. The anti-HIGD1A antibody preparation recognized an overexpressed HIGD1A-GFP fusion in HEK293T cells and endogenously expressed HIGD1A in both HEK293T cells and hippocampal neurons but did not recognize the homologous (43% sequence identical) protein HIGD1B (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Screening a broad range of hIMPs

The success of our preliminary studies spurred a more extensive coverage of the hIMP proteome. From a library of 3,270 hIMPs23, we selected an additional 135 targets in the 10–30 kDa range for P-CF expression, solubilization screening and preliminary NMR spectroscopy analysis (Supplementary Fig. 9). Overall, 111 (74%) of 150 targets expressed at considerably high levels (>1 mg ml−1 of cell-free reaction mixture; Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 6), and we used LMPG to solubilize all of them. From an analysis of [1H-15N]TROSY-HSQC spectra, we found that 38 of 100 evaluated by NMR spectroscopy targets, including the six hIMPs with solved structure, were adequate for structural studies without additional optimization (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12).

DISCUSSION

The described structural studies of hIMPs demonstrate the technological synergy between cell-free expression and CDL-aided NMR spectroscopy analysis. It has been shown previously that PRE-based constraints can be used for structure determination of β-barrel membrane proteins19 and small single-crossing helical membrane proteins18. They also have been used as additional long-range distance constraints for structure determination of multihelical membrane proteins14,24,25. Our results demonstrate that PRE-derived distances can be used as a single source of long-range constraints for structure determination of multihelical membrane proteins. A careful design of the mutants for spin labeling and a meticulous analysis of PRE data, however, are necessary because changes in protein conformation induced by mutation, high mobility of the spin-labeled residue and sparse net of long-range PRE data may affect accuracy of the structures.

The biological functions of the six hIMPs we characterized here have not yet been fully defined, and we do not know whether their structures are in the functionally relevant state. Nevertheless, knowledge of the backbone scaffolds of the proteins may provide structural insights for, for example, site-specific mutagenesis, which would help understand the fundamental functional roles of these proteins. HIGD1A and HIGD1B are likely associated with response to hypoxia26. HIGD1A has been found to be upregulated in hypoxia27; HIGD1B in prolactinomas is speculated to be associated with increased tumor hypoxia tolerance, angiogenesis and drug resistance28. FAM14B, a member of the FAM14 family encoded by interferon-stimulated gene 12c is localized in the mitochondria and may influence cellular sensitization to apoptotic stimuli via mitochondrial membrane destabilization29. Distinct from TMEM141 and TMEM14A, TMEM14C belongs to an uncharacterized protein family UPF0136_TM that is presumably involved in heme biosynthesis30. Consistently with our earlier speculation6, we predict that IMPs with tightly packed helices (TMEM14A and TMEM14C) may have a structural or transport role in the membrane, whereas IMPs with loosely packed helices (HIGD1A, HIGD1B and TMEM141) could be involved in signal transduction across the membrane.

We believe that efficient production of hIMPs by cell-free expression in combination with robust structural analysis by NMR spectroscopy has broader applications. In addition to facilitating 3D structure determination of membrane proteins by solution NMR spectroscopy, it will benefit functional and biochemical characterization of hIMPs, including individual antibody generation against hIMPs for proteomic and cell biological studies. Engineered hIMPs could also constitute a building block in biomaterial and nanoscience research.

ONLINE METHODS

Expression vector design

To enable cloning of hIMPs from a library of 3,270 hIMPs in Gateway entry vectors23, the pIVEX2.3d vector (Roche Applied Science) was Gateway-adapted and optimized. We designed two vectors, one containing several tags that allow detection and purification and one without tag, which was used for NMR spectroscopy sample preparation. pIVEX 2.3d was supplemented with a 5′ attR1 site (5′-ACAA GTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTA-3′) and a 3′ attR2 site (5′-GACCCAGCTTTCTTGTACAAAGTGGTT-3′), a thrombin cleavage site (5′-GCTGCCACGCGGCACCAG-3′), a factor Xa cleavage site (5′-ATCGAGGGCCGT-3′) and a StrepII tag (5′-TGGAGCCACCCGCAGTTCGAAAAA-3′) using suitable oligoonucleotide primers with suitable restriction sites and standard polymerase chain reaction techniques with Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolab (NEB)) following standard protocols for Gateway destination vector creation (Invitrogen). The resulting pIVEX2.3d-Gateway-tag vector (p23-GWT) encodes a protein with an N-terminal Gateway sequence (MTSLYKKVG) and a C-terminal tag (Y(or C)PTFLYKVVLVPRGSHMIEGRWSHPQ FEKYRAPGGGSHHHHHH) (Fig. 1a). For Gateway cloning of nontagged hIMPs for NMR spectral quality evaluation, a second vector pIVEX2.3d–Gateway-NMR (p23-GWN) was derived from p23-GWT by introducing a stop codon (TAA) after the 5′ att site, resulting in translation of a short 9-amino-acid C-terminal att-derived sequence (Y(or C)PTFLYKVV).

Cloning procedures

One hundred fifty hIMP targets in Gateway entry vectors (Supplementary Table 6) were cloned into p23-GWT and p23-GWN destination vectors using LR Clonase (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol with optimizations. In particular, 1 µl entry clone (150 ng/µl), 1 µl destination vector (150 ng/µl), 2 µl 5× LR Clonase reaction buffer, 4 µl TE buffer (pH 8.0) and 2 µl Gateway LR Clonase II enzyme mix (Invitrogen) were mixed and incubated for 60 min at 25 °C. Subsequently, 1 µl proteinase K solution was added and LR reaction mixture was incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. One microliter of LR reaction was transformed into 10 µl of DH5α chemically competent cells (Invitrogen) and plated on LB plates containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin. Single colonies were picked and grown overnight in 5 ml TB medium with 0.1 mg/ml ampicillin and purified using a Miniprep kit (Qiagen). The manufacturer’s protocol was optimized to enhance plasmid yield and purity. In particular, cells from 5-ml overnight cultures in TB medium were resuspended in 250 µl buffer P1, and 350 µl buffer P2 was added and mixed by gentle inversion. After 5 min, 450 µl of buffer N3 was added, mixed and centrifuged for 10 min at 20,000g. The supernatant was transferred to the QIAprep spin column connected to a vacuum manifold (Qiagen). The column was washed with 500 µl buffer PB and 750 µl buffer PE and subsequently centrifuged for 1 min at 20,000g to remove residual ethanol. Plasmid DNA was eluted with 75 µl buffer EB. Plasmids were checked by DNA sequencing and used for cell-free expression.

Expression constructs for NMR spectroscopy structural studies of HIGD1A, HIGD1B, TMEM14A, FAM14B, TMEM141 and TMEM14C were obtained by site-directed mutagenesis, introducing a stop codon (TAA) after the hIMP-encoding genes in corresponding p23-GWN vectors. Cysteine residues in HIGD1A, HIGD1B, TMEM14A, FAM14B, TMEM141 and TMEM14C as well as serine residues in HIGD1B, TMEM14A and TMEM141 for different cysteine constructs, were introduced by site-directed mutagenesis. In particular, primers were designed as described elsewhere32 and quick-change reactions were carried out using 1 µl HotStar polymerase (Qiagen), 1 × HotStar buffer, 2% DMSO, 0.2 µM primers and 3–5 µg/ml template DNA in 50 µl of reaction volume. PCR was set up in a thermocyler (Techne) at 95 °C for 0.5 min and cycled 18 times at 95 °C for 0.5 min, 55 °C for 100 s, 68 °C for 10 min with the final extension time of 30 min at 68 °C. Parental DNA was digested with DpnI (NEB) by adding 1 µl enzyme, incubated for 3 h at 37 °C and subsequently purified by a Nucleotide purification kit (Qiagen) with elution in 30 µl H2O. Seven microliters of DNA was used to transform 25 µl of DH5α chemically competent cells (Invitrogen).

For transient expression of HIGD1A-GFP and HIGD1B-GFP in HEK293T cells, the pTT5 expression vector33 was Gateway-adapted with suitable oligonucleotide primers as described above, resulting in the pTT5-Gateway destination vector encoding an N-terminal Human IgG κ signal peptide (METDTLLLWVLLLW VPGSTGAGS) followed by a His9 tag and C-terminal translated GFP. Sequences encoding HIGD1A and HIGD1B in Gateway-entry vectors were cloned into pTT5-Gateway as described above. Plasmids were checked by DNA sequencing and amplified by HighSpeed Plasmid Maxi Kit (Qiagen).

Cell-free expression

We established, optimized and fine-tuned for expression of IMPs a preparative high-throughput E. coli–based cell-free expression system. Chemicals for cell-free expression were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Stable isotope–labeled amino acids and amino acid mixtures were purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories unless otherwise stated. hIMPs were produced in an individual continuous exchange cell-free system according to previously described protocols with additional optimization. In short, cell-free extracts were prepared from the E. coli strain A19 as described previsously1,34, T7 RNA polymerase was expressed using the pT7–911Q plasmid35 and purified as described previously36. Analytical-scale reactions were performed in 20 kDa molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) Mini Slide-A-Lyzers (Thermo Scientific) using 70 µl of reaction mixture and 1 ml of feeding mixture. Mini Slide-A-Lyzers were placed in a custom made 24-well plastic block holding the feeding mixture and incubated in a shaker (New Brunswick Scientific) (Fig. 1a) for ∼15 h at 30 °C at 160 r.p.m. Preparative scale cell-free reactions were performed in 20-kDa MWCO Slide-A-Lyzers (Thermo Scientific) using 2–4 ml of reaction mixture set with the 1:17 volume ratio between reaction and feeding mixture. Slide-A-Lyzers were placed in a suitable plastic box holding the feeding mixture and incubated in a shaker (New Brunswick Scientific) for ∼15 h at 30 °C at 140 r.p.m. The conditions for the cell-free reaction were as follows: reaction mixture and feeding mixture contained 230 mM potassium acetate, 13 mM magnesium acetate, 100 mM Hepes-KOH pH 8.0, 3.5 mM Tris-acetate pH 8.2, 0.2 mM folinic acid, 0.05% sodium azide, 2% polyethyleneglycol 8000, 2 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl) phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP) (Thermo Scientific), 1.2 mM ATP, 0.8 mM each of CTP, UTP and GTP, 20 mM acetyl phosphate (Fluka), 20 mM phosphoenol pyruvate (AppliChem), 1 tablet per 50 ml complete protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science), 1 mM each amino acid, 40 µg/ml pyruvate kinase (Roche Applied Science), 500 µg/ml E. coli tRNA mix (Roche Applied Science), 0.3 unit/µl RNase inhibitor (SUPERase-In, Ambion), 0.5 unit/µl T7 RNA polymerase, 40% S30 extract and 10 µg/ml of pIVEX2.3d–derived plasmid DNA. For cell-free uniform 15N labeling, reaction mixture and feeding mixture were supplemented with 0.5 mM of [15N]algal amino acid mixture and 0.5 mM of 15N-labeled amino acids Asn, Cys, Gln and Trp. For cell-free uniformly 15N-13C, 2H-15N, 2H-15N-13C labeling, reaction mixture and feeding mixture were supplemented with 0.5 mM of correspondingly labeled amino acid mixtures. For combinatorial labeling of HIGD1A, HIGD1B and FAM14B combinations of 15N-labeled Ala, Cys, Asp, Glu, Phe, Gly, Ile, Lys, Leu, Met, Asn, Gln, Arg, Ser, Thr, Val, Trp and Tyr or 1-13C-labeled Ala, Cys, Asp, Glu, Phe, Gly, Ile, Lys, Leu, Met, Pro, Gln, Ser, Val, Trp and Tyr, and nonlabeled amino acids were used according to the schemes given in Supplementary Table 1. Uniform 2H-15N and 2H-15N-13C labeling was efficiently done in H2O.

Protein characterization

The Invitrogen gel electrophoresis system was used for all SDS-gel analyses following the manufacturer’s protocol, using 12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels in 2-(N-morpholino) ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer stained with Coomassie blue or InstantBlue (Expedeon Protein Solutions).

The expression yield was quantified by estimating expression based on Coomassie-stained protein band intensities for all 150 hIMPs. These intensities were compared to Coomassie-stained standard bands of a known protein concentration. For western blot analysis of cell-free expressed hIMPs, the gels were blotted on a 0.45 µm Immobilon-P poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane (Millipore) using Invitrogens Xcell IITM Blot Module for 1 h at 35 V. The membrane was then blocked for 1 h in blocking-buffer (1× PBS, 7% milk powder and 0.1% (w/v) Tween-20) and subsequently incubated for 1 h with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated His6-tag antibody (ab1187, Abcam) using 1: 2,000 dilution in washing buffer (1× PBS and 0.1% Tween-20). After extensive washing in washing buffer, the blots were analyzed by chemiluminescence (ECL western blot substrate, Thermo Scientific) on X-ray film (CL-XPosure, Thermo Scientific) using exposure times of 10–60 s.

For western blot analysis of HIGD1A and HIGD1A-GFP, we used polyclonal anti-HIGD1A antibody raised in rabbit (Eton Biosciences) from P-CF–expressed and LMPG-solubilized HIGD1A, or rabbit anti-GFP (full-length) antibody (sc-8334, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The gels were blotted and blocked as described above with subsequent 1 h incubation with anti-HIGD1A-IgG using 1:2,000 dilution or anti-GFP-IgG using 1:1,000 dilution in washing buffer containing 7% milk powder. After incubation with primary antibody, the membrane was washed 5 times with 100 ml washing buffer for 5 min each time, and subsequently incubated for 1 h with secondary bovine anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (sc-2370, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) using 1:3,000 dilution in washing buffer supplemented with 7% milk powder. After five 5-min washes with 100 ml washing buffer, the blots were analyzed by chemiluminescence on X-ray film using exposure of 0.5–5 min.

All cell-free expressed hIMPs were characterized by SDS-PAGE (Supplementary Fig. 10). HIGD1A, HIGD1B, TMEM14A, FAM14B, TMEM141 and TMEM14C were analyzed by light scattering coupled with size-exclusion chromatography and refracting index measurements (SEC-UV/LS/RI) (Supplementary Fig. 1). SEC-UV/LS/RI analysis of hIMP-LMPG complexes was performed by measuring the relative refractive index signal (Optilab rEX, Wyatt Technology), static light scattering signals from three angles (45°, 90° and 135°) (min-iDAWN TREOS, Wyatt Technology), and UV-light extinction at 280 nm (Waters 996 Photoiode Array Detector, Millipore) during size-exclusion chromatography (HPLC, Waters 626 Pump, 600S Controller, Millipore) with polymer column (Shodexfi Protein KW-802.5). hIMPs were analyzed by injecting 100 µl of 200 µM hIMP solubilized in LMPG into high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) buffer (20 mM MES-Bis-Tris pH 6.0 and 150 mM NaCl) supplemented with 0.01% LMPG at 0.8 ml/min. The fractions, containing target proteins, were concentrated in 5 kDa MWCO Vivaspin2 concentrators (Sartorius Stedim Biotech) to 20–50 µl and reloaded on the column. The oligomeric state of HIGD1B in FC12, DDM and DM micelles was analyzed by SEC-UV/LS/RI. HIGD1B was solubilized in 100 µl of a buffer (20 mM MES-Bis-Tris pH 6.0 and 150 mM NaCl) containing selected detergent (20 mM, 30 mM and 75 mM for FC12, DDM and DM, respectively). The final protein concentration was 150–200 µM. The samples were injected into HPLC buffer supplemented with 1.6 mM FC12. The data were collected and analyzed using the Astra V 5.3.2.12 Software (Wyatt Technology Corp.). The average molar weights of the protein-detergent complex, the protein and the detergent fraction in the complex (Supplementary Fig. 1 and 2) were calculated by the Protein Conjugate module of the Astra program. The oligomeric state of HIGD1B in DDM and DM could not be derived by the Astra V Software from SEC-UV/LS/RI data due to the overlap of protein-detergent micelles with empty detergent micelles as shown for HIGD1B in the presence of DDM (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Nevertheless the elution volumes of the HIGD1B protein peak in the four detergents (Supplementary Fig. 2) are nearly identical, which suggests that HIGD1B in the presence of DDM and DM is most likely monomeric.

Detergent solubilization

All 150 P-CF-expressed hIMPs were analyzed for detergent solubilization in seven different detergents. Detergent solubilization was tested in 70 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), 42 mM 1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)] (LMPG), 100 mM n-decylphosphocholine (FC10), 100 mM n-dodecylphosphocholine (FC12), 250 mM n-decyl-β-d-maltoside (DM), mixture of 196 mM n-dodecyl-β-d-maltoside (DDM) with 41 mM cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHS) and 100 mM lauryldimethylamine-N-oxide (LDAO). Seven samples of 7 µl of P-CF precipitate resuspended in buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.4 and 150 mM NaCl) were centrifuged for 10 min at 20,000g. The supernatant was removed, and 7 µl of SDS, LMPG, FC10, FC12, DM, DDM/CHS and LDAO were added to the respective precipitate samples. The precipitate was resuspended by pipetting 10–20 times and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The residual precipitate was pelleted by centrifugation for 15 min at 20,000g and 1–4 µl of the supernatant, depending on hIMP expression, was loaded with 5 µl of 2× SDS sample buffer on a 12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen) and run in MES buffer for 52 min at 200 V. The gel was stained with InstantBlue and analyzed for expression based on band intensity.

NMR spectroscopy sample preparation

All hIMPs were expressed as precipitate (P-CF) in the absence of detergents1. The only gene expressing in the cell-free system is the target protein gene; therefore, the only labeled protein is the target protein. This, in combination with the fact that the SEC-UV/LS/RI data showed our target proteins to be homogeneous protein-detergent complexes, allows us to conclude that co-precipitated endogenous cell-free extract proteins will not influence NMR structural studies. Therefore, additional purification of the proteins is not crucial. Precipitated recombinant proteins were removed from the reaction mixture by centrifugation at 20,000g for 15 min and washed in two steps. First, to remove co-precipitated RNA, precipitates were suspended in 50% volume equal to the reaction mixture volume in 20 mM MES-Bis-Tris buffer pH 6.0, 0.01 mg/ml RNase A and shaken at 900 r.p.m. and 37 °C for 30 min. After incubation, precipitates were collected by centrifugation at 20,000g for 10 min and suspended in 100% volume equal to the reaction mixture volume in NMR buffer (20 mM MES-Bis-Tris pH 6.0). NMR spectroscopy samples were prepared from washed precipitate of 1–4 ml reaction mixture by solubilization in 300 µl 3% (wt/vol) LMPG in NMR buffer for all tested hIMPs except HIGD1A, HIGD1B and TMEM141, which were solubilized in 2% LMPG (wt/vol) in NMR buffer. The suspension was sonicated in a water bath sonicator (Bransonic) for 1 min and subsequently incubated for 15 min with shaking at 900 r.p.m. and 37 °C, followed by centrifugation at 20,000g for 10 min. NMR spectroscopy samples were pH-adjusted and supplemented with 5% D2O and 0.5 mM 4,4-dimethyl-4-silapentane-1-sulfonic acid (DSS). For 13C and 15N NOESY NMR spectroscopy experiments requiring deuterated detergent, hIMP NMR spectroscopy samples were prepared by solubilization in 2% d27-LMPG (wt/vol) (FBReagents). D27-LMPG was used to minimize the spectral distortion and the impact from 1H signals of the detergent in 13C-NMR spectroscopy experiments with HIGD1B, TMEM14A and TMEM141. Shigemi NMR tubes were used for solution NMR measurements. ‘Fingerprint’ spectra of the cell-free-expressed hIMPs, categorized as good, are shown in Figure 2 and Supplementary Figures 11 and 12.

Cysteine mutagenesis and spin-labeling

For PRE experiments, 5–9 single-cysteine mutants were prepared for HIGD1A, HIGD1B, TMEM14A, FAM14B, TMEM141 and TMEM14C. Cysteine-free mutants were prepared for HIGD1B, TMEM14A and TMEM141 (Supplementary Table 3). The single cysteine mutants prepared for each of the six selected hIMPs are listed in Supplementary Table 3 and illustrated in Supplementary Figure 4. Positions for cysteine introduction were chosen based on the following criteria: mutations were located in regions containing helices, which were predicted by chemical shifts, and 3–4 residues adjoining the helix; each helix was labeled in at least two positions close to its ends; mutated residues had minimal structural and/or functional importance; the preferred amino acids for cysteine mutagenesis were serine, threonine and alanine; in the case there were no appropriate serine, threonine or alanine; residues close to the region of interest, valine, leucine, glutamine and aromatic tyrosine and phenylalanine residues were the second choice. Preservation of the structure in single-cysteine mutants was tested by TROSY-HSQC experiments as disruption of helical packing by the spin label would provide strong changes in chemical shifts and would diminish the overall quality of the TROSY spectra. All single-cysteine mutants gave minimal changes in TROSY-HSQC spectra upon introduction of the mutations. Even though we followed the selection procedure described above, we still had few single-cysteine mutants for which satisfactory PRE data were not obtained. For example, PRE effect in 1-oxyl-(2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-Δ3-pyrroline-3-methyl)methanethiosulfonate (MTSL)-labeled TMEM14A(S74C) affected only amide groups from neighboring residues (not more than 10 amino acids away from the labeled cysteine in the protein sequence). Other than that, PRE data from the paramagnetic label attached to a cysteine in non-transmembrane terminal helices require careful analysis, because of high mobility of the helix and attached label. The 15N-labeled single-cysteine mutants were prepared from 2–4 ml cell-free reaction mixture. To eliminate problems with (i) incomplete reduction of the spin-label in a detergent-solubilized protein and (ii) changes in chemical shifts caused by incorporation of a label, we used parallel labeling with structurally similar paramagnetic and diamagnetic labels as suggested in ref. 19. Every cysteine mutant was labeled with paramagnetic spin-label MTSL and with diamagnetic label 1-acetyl-(2,2,5,5-tetrametyl Δ3-pyrroline-3-methyl)methanethiosulfonate (DML) (both from Toronto Research Chemicals). The cysteine-free mutants or cysteine-free wild-type proteins were used as a control of nonspecific MTSL binding to the protein and/or detergent and were ‘labeled’ with MTSL only. For the labeling, the 15N-labeled NMR spectroscopy samples were split in half and supplemented with 5 mM MTSL or DML, solubilized in acetonitrile. After overnight incubation at room temperature, the excess of MTSL and DML was removed by washing in 5-kDa MWCO Vivaspin 2 concentrators (Sartorius Stedim Biotech). Labeled samples were washed 3 times by concentrating to 100 µl, resuspending in 2 ml NMR buffer and concentrating to 100 µl. After the third wash the samples were concentrated to 300 µl, supplemented with 5% D2O and 0.5 mM DSS and measured in a Shigemi NMR tube.

NMR spectroscopy experiments

NMR spectra of hIMPs were recorded at 37 °C on a Bruker AVANCE 700 MHz spectrometer equipped with five radiofrequency channels and a triple-resonance cryoprobe with a shielded z-gradient coil. For the combinatorial assignment, [15N,1H]TROSY-HSQC and 15N,1H plane of the TROSY-HNCO12,37 were measured for each selectively 15N,13C-labeled sample. For the traditional assignment of backbone 1H, 15N and 13C resonances TROSY-based experiments, HNCA, HNCO38, HNCACB, HNCOCA, HNCOCACB and HNCACO39 as well as gradient-enhanced 3D 1H-15N-NOESY-TROSY (mixing time, 120 ms) were used. Partial side chain assignment was performed using 3D 1H-15N-NOESY-TROSY and 3D 1H-13C-HSQC-NOESY–1H-15N-HSQC40 experiments. The PRE effect was measured using [15N,1H]TROSY-HSQC spectra collected for all cysteine mutants before spin labeling and after MTSL and DML labeling. Protein localization within LMPG micelles was checked by detection of a relaxation effect on [15N,1H]TROSY-HSQC spectra of the hIMPs from water-soluble relaxation agent Gd3+-DOTA (Molecular Probes)41. HIGD1B was measured with different concentrations of Gd3+-DOTA (0 mM, 2.5 mM, 5.0 mM and 10 mM). After analysis of the relaxation effect using ratios of intensities in original (0 mM Gd3+-DOTA) and paramagnetic samples (Supplementary Fig. 3a), the 5.0 mM concentration was chosen to test the other hIMPs. The detected Gd3+-DOTA effect (Supplementary Fig. 3) confirmed the transmembrane topologies for the calculated hIMPs structures. Protein-detergent NOEs were derived using 3D 1H-15N-NOESY-TROSY experiments. The spectra were collected with 200-ms mixing time for the 15N,2H-labeled proteins (to achieve full protonation of amides, the proteins were expressed and samples were prepared using H2O) in protonated LMPG.

NMR signal assignment and spectra analysis

NMR spectra were transformed using Topspin (Bruker Biospin) and ProSA programs. Spectra analysis and assignment were performed using the CARA program. Combinatorial assignment using CDL strategy6 was used to accelerate assignment procedure. Built on the established principles of combinatorial assignment42,43, the CDL strategy generates a sequence-dependent labeling scheme for 5–8 samples6. The samples are expressed in the P-CF mode and selectively 15N,13C-labeled according to this scheme (see, for example, schemes for hIMPs in Supplementary Table 1). Analysis of the cross-peaks in paired TROSY-HSQC and 2D HNCO experiments allowed unambiguous assignment of those NH cross-peaks that correspond to unique amino acid pairs in the protein sequence. Other cross-peaks, with two or more possible assignments, are assigned to an amino acid type. The schemes for CDL assignment were calculated using MCCL program6 and consisted of 6, 6 and 5 samples for HIGD1A, HIGD1B and FAM14B, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). The selectivity of isotope labeling in cell-free reaction can be affected by amino acid scrambling. The most prominent examples are the pairs Gly-Ser, Asn-Gln, Asp-Glu and Asp-Asn. To avoid possible problems and facilitate CDL assignment, we modified the MCCL algorithm (http://sbl.salk.edu/combipro/) by incorporating user-defined identical labeling for any selected group of amino acids. In case of any uncertainty, the assignment can be verified using conventional sequential assignment methods.

Calculation of PRE-based distance constraints

PRE distance constraints were introduced for distances between an amide proton and Cβ atom of residue, mutated to a cysteine for the paramagnetic labeling. Distance constraints were derived from the measured PRE effect using the procedures described in19,21,44,45. All the spectra were transformed in the same way and the intensities of 15N-1H cross-peaks in the MTSL (Ip) and DML (Id) samples were measured using the CARA program. The ratios of intensities (Ip/Id) were normalized against a set of 8–12 highest Ip/Id ratios, which were assumed to belong to cross-peaks unaffected by PRE. For TMEM141, the PRE distance constraints were derived by qualitative assessment of the Ip/Id ratios and were categorized based on intra- or inter-helical contacts between the spin label and the affected amide group as described45. PRE distance constraints for HIGD1A, HIGD1B, TMEM14A, FAM14B and TMEM14C were calculated using the modified Solomon-Bloembergen equation (equation (5) in ref. 21). The transverse relaxation rate enhancement was obtained from normalized intensity ratios (Ip/Id) as previously described, and the correlation time for the electron-nuclear spin interaction was estimated as the global rotational correlation time of the protein-detergent complex calculated using the Stokes-Einstein equation (Table 1). Such rough estimation of the correlation time is sufficient enough because, as mentioned earlier21, even moderate 20% error in estimation of the correlation time gives only ∼0.5 Å error in calculated distance. For cross-peaks with the ratios below 0.15, no lower distance constraints were used, whereas upper constraints were set to 12 Å for distances between stable regions and to 15 Å if a spin label or amide group were located in flexible regions. For cross-peaks with the ratios above 0.9, only lower distance constraints equal to 25 Å were introduced. The upper distance constrains between flexible or unstructured regions were excluded from calculation. The upper and lower distance constraints for the peaks with Ip/Id ratios between 0.15 and 0.9 were generated from PRE-calculated distances using ± 4 Å margins. During structure calculation the margins were reduced to ± 3 Å for constraints between structured transmembrane regions if this change did not increase the Cyana penalty function. We assumed that the initial ± 4 Å margins in distance constraints are sufficient to cover the possible errors resulting from the use of a uniform correlation time, the uncertainty of the estimation of the intrinsic relaxation rates and the ‘r−6’-averaging of the nitroxide group motion. It was shown that the whole side chain of cysteine with attached MTSL (R1) has reduced mobility in both water-soluble and membrane proteins46,47. In the studied membrane leucine transporter46, the nitroxide rings interact with the hydrophobic protein surface, thus fixing the whole R1 side chain.

We found that PRE-derived lower distance constraints are important for the calculation of helical bundle structures and especially for the determination of relative orientations of the transmembrane helices. As the only physical constraints of an α-helical bundle are van der Waals interactions, it has to have additional lower limit constrains from experimental data to prevent collapsing of the bundle. In contrast, others had reported that lower constraints were insignificant in the calculation of the β-barrel structure of OmpA19. This is not surprising because a β-barrel is restrained by the local geometry of inter-strand contacts and by the constant network of these contacts.

As precision of the PRE-derived distance constraints is low, for successful structure calculation it is important to obtain as many meaningful constraints as possible. In theory, for every HN group from a given helical region the number of PRE-based distance constraints should be equal to the number of cysteine mutants used for spin-labeling. In reality, this number is lower due to signal overlapping and meaningless constraints like those between neighboring atoms within the same transmembrane helices. The average number of upper distance constraints per restrained residue ranged from 3.63 (HIGD1A) to 4.64 (FAM14B) for the studied hIMPs. According to ref. 48, approximate global fold can be determined with as few as 1.4 constraints per residue, whereas at least 3 constraints per residue are required for low- to medium-resolution NMR spectroscopy structures.

Structure calculation and analysis

The 13Cα, 13Cβ and 13CO chemical shift deviations from random coil values were used to define backbone torsion angle restraints49. Sequential distance constraints were derived from the integral intensities of NOE cross-peaks measured in 3D 15N-resolved TROSY-[1H;1H]-NOESY (mixing time 120 ms). The hydrogen bond constraints were generated for the helical regions defined by chemical shift analysis. An interactive procedure, which included structure calculation by the CYANA program50 followed by the distance constraints refinement, was used to calculate the backbone spatial structures of the hIMPs. The structures were calculated using a simulated annealing protocol (1,000 high-temperature steps followed by 9,000–11,000 cooling down steps and 1,300 steps of a conjugate gradient minimization) and the default CYANA force field. The summary of the constraints used in the calculation of the structures is presented in Table 1. Long-distance constraints used in structure calculation are shown in Figure 3b. The 20 conformers with the lowest target function of the last CYANA calculation cycle were selected from 200 calculated structures. The helical packing parameters, such as interhelical crossing angles and helical kinks, were derived for the final sets of 20 structures with the Helix Packing Pair51 and Molmol52 programs. The structures were visualized and analyzed in Molmol program; statistics for interatomic distances (average value and deviation) in the sets of structures were calculated using atomDistancer program.

Cell culture

Human embryonic kidney cells HEK293T were grown in DMEM medium (Mediatech) supplemented with 10% FCS in humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Primary cultures of hippocampal neurons were prepared from 0–2-d-old Sprague Dawley rat pups using a modification of a previously described method53. Briefly, the hippocampi were dissected from brain and dissociated with papain (Worthington), and the neurons were plated at 25,000 cells/cm2 onto 12-mm glass cover slips (Warner Instruments) coated with 0.2 mg/ml poly-d-lysine (BD). Hippocampal neurons were cultured in Neurobasal medium supplement with B27, 100 U/ml streptomycin and 100 µg/ml penicillin (Invitrogen) at 37 °C and in 5% CO2 for 10–14 d. The medium was replaced the day after plating and twice weekly thereafter. All the procedures were approved by the Salk Institute’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Heterologous expression of hIMP proteins in human cell line

HEK293T cells were grown to 90–95% confluence and transiently transfected with DNA encoding for the indicated proteins using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Forty-eight hours after transfection, cell culture medium was aspirated, and cells were washed twice with PBS. Cell were then placed on ice and lysed with mild lysis solution (Immunocatcher kit, CytoSignal Research Products) supplemented with protein inhibitors (Complete, Mini, Roche Applied Science).

Immunofluorescence and imaging

Culture medium was aspirated from cell cultures, followed by a brief wash with PBS. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, washed and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton-X in PBS (10 min). Unspecific binding was blocked by 30 min incubation with 3% BSA solution in PBS. Cells were then incubated with primary rabbit anti-HIGD1A antibody diluted 1:5,000 in blocking solution for 1 h, washed thoroughly with PBS and incubated over 1 h with secondary anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated antibody (1:400 dilution, A-21244, Invitrogen). After the final wash with PBS, cells were mounted using ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen) and imaged with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 710) using a 63× objective with oil immersion. The differential image contrast (DIC) was corrected using ImageJ Pseudoflatfield Filter followed by adjustment of brightness and contrast.

Pictures of live HEK293T cell transfected with vectors encoding GFP fusion proteins were taken using a Nikon Eclipse TE300 inverted microscope equipped with a high-pressure mercury lamp and a GFP set of filters and beam splitters (Excitation filter HQ480/40x; dichroic mirror Q505LP, Emission filter HQ525/ 50m, Chroma) and a Nikon D70 digital camera.

Modeling leverage calculations

The modeling leverage of the six hIMP NMR spectroscopy structures was estimated by the ModPipe, comparative modeling pipeline54 accessible through the ModWeb web server (http://salilab.org/modweb/) (Supplementary Table 5). We relied on the ModWeb option that accepts a protein structure as input, calculates a multiple sequence profile and identifies all homologous sequences in the UniProtKB database55, followed by modeling these homologs based on the user-provided structure. These models are available in ModBase through a summary page (http://modbase.compbio.ucsf.edu/modbase-cgi/model_leverage.cgi?type=master_salk). On average, each structure allowed us to model with relatively high accuracy 171 related unique protein sequences, based on more than 30% sequence identity and using at least 50% of the residues in the structures as templates. Another 114 protein sequences on average could also be modeled, but at lower accuracy, primarily because of the target-template alignment errors.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank G. Louie for comments in preparation of the manuscript, A.S. Arseniev for suggestions on the spin-labeling procedure and S. Maslennikov for writing the atomDistancer program. C.K. thanks the Pioneer Foundation for a Pioneer Fund Postdoctoral Scholar Award. This work has been partly supported by US National Institutes of Health (S.C.: GM098630, GM095623; A.S. and U.P.: GM094662, GM094625 FDP, and GM54762), Incheon Free Economic Zone and the World Class University Program (Korea).

Footnotes

Accession codes. PDB: HIGD1A, 2LOM; HIGD1B, 2LON; FAM14B, 2LOQ; TMEM141, 2LOR; TMEM14A, 2LOO and 2LOP; and TMEM14C, 2LOS.

Note: Supplementary information is available in the online version of the paper.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.K., I.M., W.K., R.R. and S.C. designed experiments, C.K., E.J.C.C., L.E. and J.H.J.K. cloned hIMP targets, performed cell-free expression, evaluated protein expression levels and detergent solubilization; C.K. and E.J.C.C. created single cysteine mutants for PRE experiments, prepared isotopically labeled NMR spectroscopy samples and samples for PRE measurements. C.K. and I.M. recorded NMR spectra and evaluated NMR spectral quality of tested hIMPs; C.K., I.M., M.B., C.E., N.V., E.J.C.C. and K.B. collected and assigned NMR spectra and analyzed data; I.M., M.B. and C.E. calculated the structures. C.K., E.J.C.C., B.B. and P.A.S. analyzed HIGD1A antibody specificity by western blot and by immunostaining; U.P. and A.S. calculated modeling leverage based on hIMP structures; C.K., I.M., W.K. and S.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Klammt C, et al. High level cell-free expression and specific labeling of integral membrane proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:568–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2003.03959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wuu JJ, Swartz JR. High yield cell-free production of integral membrane proteins without refolding or detergents. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1778:1237–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Katzen F, et al. Insertion of membrane proteins into discoidal membranes using a cell-free protein expression approach. J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:3535–3542. doi: 10.1021/pr800265f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalmbach R, et al. Functional cell-free synthesis of a seven helix membrane protein: in situ insertion of bacteriorhodopsin into liposomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;371:639–648. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klammt C, et al. Evaluation of detergents for the soluble expression of alpha-helical and beta-barrel-type integral membrane proteins by a preparative scale individual cell-free expression system. FEBS J. 2005;272:6024–6038. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maslennikov I, et al. Membrane domain structures of three classes of histidine kinase receptors by cell-free expression and rapid NMR analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:10902–10907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001656107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klammt C, et al. Polymer-based cell-free expression of ligand-binding family B G-protein coupled receptors without detergents. Protein Sci. 2011;20:1030–1041. doi: 10.1002/pro.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Junge F, et al. Modulation of G-protein coupled receptor sample quality by modified cell-free expression protocols: a case study of the human endothelin A receptor. J. Struct. Biol. 2010;172:94–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keller T, et al. Cell free expression and functional reconstitution of eukaryotic drug transporters. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4552–4564. doi: 10.1021/bi800060w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klammt C, et al. Functional analysis of cell-free-produced human endothelin B receptor reveals transmembrane segment 1 as an essential area for ET-1 binding and homodimer formation. FEBS J. 2007;274:3257–3269. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishihara G, et al. Expression of G protein coupled receptors in a cell-free translational system using detergents and thioredoxin-fusion vectors. Protein Expr. Purif. 2005;41:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pervushin K, Riek R, Wider G, Wuthrich K. Attenuated T2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gautier A, et al. Structure determination of the seven-helix transmembrane receptor sensory rhodopsin II by solution NMR spectroscopy. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010;17:768–774. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Horn WD, et al. Solution nuclear magnetic resonance structure of membrane-integral diacylglycerol kinase. Science. 2009;324:1726–1729. doi: 10.1126/science.1171716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Pielak RM, McClintock MA, Chou JJ. Solution structure and functional analysis of the influenza B proton channel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:1267–1271. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hiller S, et al. Solution structure of the integral human membrane protein VDAC-1 in detergent micelles. Science. 2008;321:1206–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.1161302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bayrhuber M, et al. Structure of the human voltage-dependent anion channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:15370–15375. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808115105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Page RC, et al. Backbone structure of a small helical integral membrane protein: A unique structural characterization. Protein Sci. 2009;18:134–146. doi: 10.1002/pro.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang B, Bushweller JH, Tamm LK. Site-directed parallel spin-labeling and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement in structure determination of membrane proteins by solution NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:4389–4397. doi: 10.1021/ja0574825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iwahara J, Schwieters CD, Clore GM. Ensemble approach for NMR structure refinement against (1)H paramagnetic relaxation enhancement data arising from a flexible paramagnetic group attached to a macromolecule. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:5879–5896. doi: 10.1021/ja031580d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Battiste JL, Wagner G. Utilization of site-directed spin labeling and high-resolution heteronuclear nuclear magnetic resonance for global fold determination of large proteins with limited nuclear overhauser effect data. Biochemistry. 2000;39:5355–5365. doi: 10.1021/bi000060h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kay LE. Solution NMR spectroscopy of supra-molecular systems, why bother? A methyl-TROSY view. J. Magn. Reson. 2011;210:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rual JF, et al. Human ORFeome version 1.1: a platform for reverse proteomics. Genome Res. 2004;14:2128–2135. doi: 10.1101/gr.2973604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sobhanifar S, et al. Structural investigation of the C-terminal catalytic fragment of presenilin 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:9644–9649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000778107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Y, et al. NMR solution structure of the integral membrane enzyme DsbB: functional insights into DsbB-catalyzed disulfide bond formation. Mol. Cell. 2008;31:896–908. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bedo G, et al. Characterization of hypoxia induced gene 1: expression during rat central nervous system maturation and evidence of antisense RNA expression. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2005;49:431–436. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.041901gb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kasper LH, Brindle PK. Mammalian gene expression program resiliency: the roles of multiple coactivator mechanisms in hypoxia-responsive transcription. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:142–146. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.2.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jiang Z, Gui S, Zhang Y. Analysis of differential gene expression by fiber-optic BeadArray and pathway in prolactinomas. Endocrine. 2010;38:360–368. doi: 10.1007/s12020-010-9389-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheriyath V, Leaman DW, Borden EC. Emerging roles of FAM14 family members (G1P3/ISG 6–16 and ISG12/IFI27) in innate immunity and cancer. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:173–181. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nilsson R, et al. Discovery of genes essential for heme biosynthesis through large-scale gene expression analysis. Cell Metab. 2009;10:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng L, Baumann U, Reymond JL. An efficient one-step site-directed and site-saturation mutagenesis protocol. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shi C, et al. Purification and characterization of a recombinant G-protein-coupled receptor, Saccharomyces cerevisiae Ste2p, transiently expressed in HEK293 EBNA1 cells. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15705–15714. doi: 10.1021/bi051292p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klammt C, Schwarz D, Dotsch V, Bernhard F. Cell-free production of integral membrane proteins on a preparative scale. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;375:57–78. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-388-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ichetovkin IE, Abramochkin G, Shrader TE. Substrate recognition by the leucyl/phenylalanyl-tRNA-protein transferase. Conservation within the enzyme family and localization to the trypsin-resistant domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:33009–33014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.52.33009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savage DF, et al. Cell-free complements in vivo expression of the E. coli membrane proteome. Protein Sci. 2007;16:966–976. doi: 10.1110/ps.062696307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riek R, et al. Solution NMR techniques for large molecular and supramolecular structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12144–12153. doi: 10.1021/ja026763z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salzmann M, et al. TROSY in triple-resonance experiments: new perspectives for sequential NMR assignment of large proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:13585–13590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salzmann M, et al. TROSY-type triple-resonance experiments for sequential NMR assignments of large proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:844–848. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Diercks T, Coles M, Kessler H. An efficient strategy for assignment of cross-peaks in 3D heteronuclear NOESY experiments. J. Biomol. NMR. 1999;15:177–180. doi: 10.1023/A:1008367912535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hilty C, Wider G, Fernandez C, Wuthrich K. Membrane protein-lipid interactions in mixed micelles studied by NMR spectroscopy with the use of paramagnetic reagents. ChemBioChem. 2004;5:467–473. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yabuki T, et al. Dual amino acid-selective and site-directed stable-isotope labeling of the human c-Ha-Ras protein by cell-free synthesis. J. Biomol. NMR. 1998;11:295–306. doi: 10.1023/a:1008276001545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kainosho M, Tsuji T. Assignment of the three methionyl carbonyl carbon resonances in Streptomyces subtilisin inhibitor by a carbon-13 and nitrogen-15 double-labeling technique. A new strategy for structural studies of proteins in solution. Biochemistry. 1982;21:6273–6279. doi: 10.1021/bi00267a036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Horn WD, Beel AJ, Kang C, Sanders CR. The impact of window functions on NMR-based paramagnetic relaxation enhancement measurements in membrane proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Roosild TP, et al. NMR structure of Mistic, a membrane-integrating protein for membrane protein expression. Science. 2005;307:1317–1321. doi: 10.1126/science.1106392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kroncke BM, Horanyi PS, Columbus L. Structural origins of nitroxide side chain dynamics on membrane protein alpha-helical sites. Biochemistry. 2010;49:10045–10060. doi: 10.1021/bi101148w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Langen R, Oh KJ, Cascio D, Hubbell WL. Crystal structures of spin labeled T4 lysozyme mutants: implications for the interpretation of EPR spectra in terms of structure. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8396–8405. doi: 10.1021/bi000604f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clore GM, Robien MA, Gronenborn AM. Exploring the limits of precision and accuracy of protein structures determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Mol. Biol. 1993;231:82–102. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lubingbuhl P, Szyperski T, Wuthrich K. Statistical basis for the use of 13Ca chemical shifts in protein structure determination. J. Magn. Reson. B. 1995;109:229–233. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guntert P. Automated NMR structure calculation with CYANA. Methods Mol. Biol. 2004;278:353–378. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-809-9:353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dalton JA, Michalopoulos I, Westhead DR. Calculation of helix packing angles in protein structures. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1298–1299. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Koradi R, Billeter M, Wuthrich K. MOLMOL: a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:51–55. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brewer GJ, Torricelli JR, Evege EK, Price PJ. Optimized survival of hippocampal neurons in B27-supplemented Neurobasal, a new serum-free medium combination. J. Neurosci. Res. 1993;35:567–576. doi: 10.1002/jnr.490350513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pieper U, et al. ModBase, a database of annotated comparative protein structure models, and associated resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D465–D474. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bairoch A, et al. The Universal Protein Resource (UniProt) Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D154–D159. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.