Abstract

Full mouth rehabilitation with fixed prosthodontics can be a time- and labor-intensive process. The use of provisional restorations allows the treating clinician to determine the functional and esthetic requirements of the definitive prostheses. However, in the case of full mouth rehabilitation, the individual preparation of provisional restorations for multiple teeth may complicate the provisional phase and increase the treatment time. This article describes a method to simplify the indirect fabrication of provisional restorations for full mouth reconstruction. Provisional restorations may be easily achieved by splinting the provisional restorations in sextants, trimming them according to red pencil marks around the prepared margins as guidelines, and fitting them in the laboratory, utilizing a second set of solid casts for the prepared teeth.

Keywords: Fabrication of provisional, Fixed prosthodontics, Indirect technique, Provisional restorations, Full mouth rehabilitation

1. Introduction

The use of provisional restorations is considered mandatory during fixed prosthodontic therapy. The importance of providing interim treatment with provisional restorations becomes critical in cases of full mouth reconstruction, in which multiple teeth are prepared. In these situations, provisional restorations will typically be used for relatively long periods of time (6–12 weeks) to monitor patient comfort and satisfaction and to allow for any necessary adjustments (Rivera-Morales and Mohl, 1992). Provisional restorations, when used for such long periods of time, must fulfill biological and mechanical requirements (Bral, 1989). For example, provisional restorations must maintain the health of the pulpal and periodontal tissues of the tooth (Bral, 1989; Gratton and Aquilino, 2004).

To protect the exposed dentinal tubules of the vital teeth and to prevent the microleakage contamination of endodontically treated teeth, it is important to maintain the marginal integrity of provisional restorations for prepared teeth (Gratton and Aquilino, 2004). In addition to providing pulpal protection, proper marginal integrity helps to maintain the health of the surrounding gingival tissues (Gratton and Aquilino, 2004). Appropriately adapted provisional restorations have a proper marginal extension at the finish line and an adequate emergence profile from the gingival margin to the axial contour height (Gratton and Aquilino, 2004; Vahidi, 1987). Overextended margins of provisional restorations may lead to gingival recession, and underextended margins may cause gingival inflammatory proliferation and overgrowth (Vahidi, 1987). Therefore, treating clinicians should make every effort to produce biologically acceptable and properly fabricated provisional restorations.

This article describes a unique method for transferring the exact marginal location of the prepared teeth to the acrylic materials of provisional restorations during the use of an indirect fabrication technique for multiple single teeth in the full mouth reconstruction case.

2. Laboratory procedure

After the teeth preparation process was completed and finalized, an impression of the prepared teeth was made with polyvinyl siloxane impression materials (Aquasil Ultra Extra; Dentsply Int., York, PA) loaded onto a stock tray (Rim-Lock; Dentsply Int.). The impression was poured twice in a fast-setting plaster (Snap-Stone Whip Mix Corp.) to obtain two sets of casts. A matrix from elastomeric impression materials (Reprosil Dentsply Caulk Putty; Dentsply Int.) was made by duplicating the diagnostic wax-up (Fig. 1a and b). Provisional restorations were fabricated from duplicates of the diagnostic wax-up, to ensure the suitability of the proposed treatment parameters, such as the centric relation, vertical dimension of occlusion, occlusal scheme of posterior teeth, anterior tooth position, and lip support (Rivera-Morales and Mohl, 1992; Gratton and Aquilino, 2004).

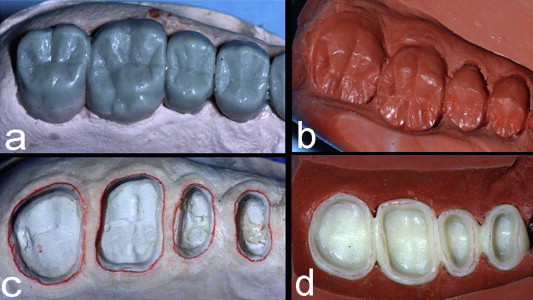

Figure 1.

(a) and (b) Close-up views of the wax-up and the matrix for a posterior sextant. (c) Close-up view showing the red pencil marks outlining the margins of the prepared teeth. (d) Close-up view of the fully polymerized (sectioned in sextants) and trimmed provisional restorations. Note that the transferred pencil marks were an excellent guide for proper trimming.

On the two obtained casts, the margins of all the prepared teeth were marked with a red Colorbrite pencil (Fig. 1c). Two coats of die spacer material (Rubber Sep; George Taub Products and Fusion Co., Inc., Jersey City, NJ) were painted on all of the prepared teeth and the adjacent tissues on the cast. The die spacer acted as a relief for the provisional materials. The advantage of the die spacer over the other commonly used separating media (e.g., petroleum jelly and tin foil substitute) is that it allows the transfer of the red line mark at the marginal areas to the completely polymerized provisional materials. Thus, the clinician can very clearly identify the margin locations after polymerization.

After the desired shade was selected, the polymethyl methacrylate provisional material (ALIKE; GC America Inc., Alsip, IL) was mixed according to manufacturer’s instructions and loaded into the matrix. The provisional material was monitored very carefully. As soon as it became dull (early doughy stage), the matrix was immediately seated firmly onto one of the obtained casts. The matrix was stabilized by an elastic band, and the cast was placed in a pressure pot (Acri-Dense III, GC Dental, Scottsdale, AZ) containing warm water for 10 min at 20 p.s.i., to improve the density and physical properties of the polymerized provisional restorations (Gratton and Aquilino, 2004; Vahidi, 1987). The cast was retrieved from the pressure pot, and the matrix was removed to recover the completely polymerized provisional restorations. At this stage, the restorations were recovered as a single unit, and the breakage of the dies was inevitable (the second obtained cast was utilized for the final fitting of the restorations).

Single unit provisional restorations were sectioned into three pieces, and each sextant was splinted individually (right and left posterior and anterior sextants). Excess materials were trimmed, and the restorations were contoured, by using the red mark lines indicating the marginal area of the prepared teeth as guidelines (Fig. 1d). This laboratory step is crucial because proper adaptation and contouring of the provisional restorations help to ensure adequate retention and resistance in the prepared teeth (Aquilino, 2004).

After the trimming, contouring, and finishing steps were completed, the restorations were fitted onto the second cast. The embrasure areas of the splinted restorations were kept accessible for cleaning and adequate hygiene maintenance (Fig. 2). As needed, special characterization and staining were performed with Minute Stain material (Minute Stain; George Taub Products and Fusion Co., Inc.) (Figs. 3 and 4).

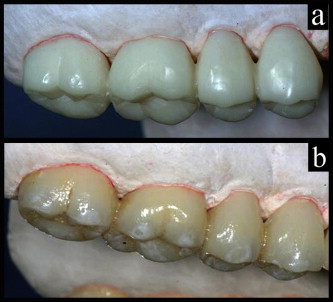

Figure 2.

Close-up buccal view of a single splinted sextant of provisional restorations. Note proper marginal integrity and embrasures. (a) After finishing. (b) After special characterization and glazing.

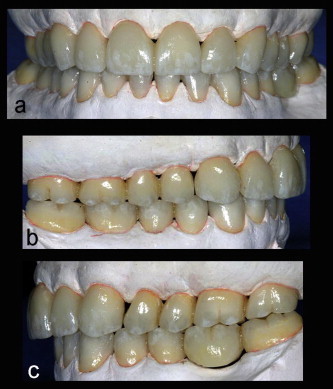

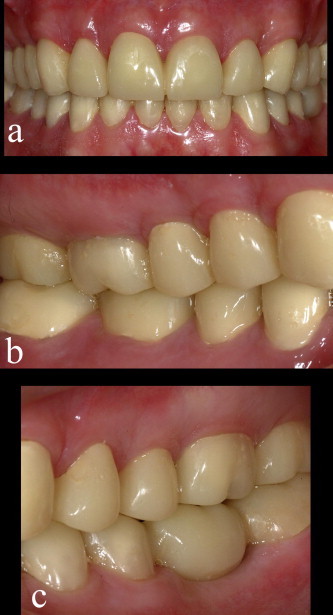

Figure 3.

Buccal views of provisional restorations after trimming, finishing, fitting and final characterization. (a) Frontal view. (b) Right lateral buccal view. (c) Left lateral buccal view.

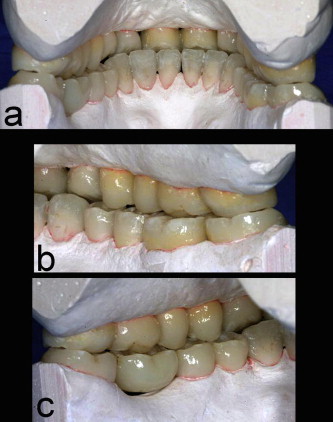

Figure 4.

Lingual views of provisional restorations after trimming, finishing, fitting and final characterization. (a) Lingual view. (b) Right lateral lingual view. (c) Left lateral lingual view.

3. Discussion

Gingival inflammation resulting in recession or overgrowth may be caused by the splinting of multiple prepared teeth with a single provisional restoration (Newman et al., 2006), if proper contour and embrasures with highly polished plaque-resistant surfaces are not achieved. However, multiple prepared teeth may be splinted if the biological requirements for the provisional restorations are met and if the patient practices adequate oral hygiene (Bral, 1989).

An indirect fabrication method of individual (nonsplinted) provisional restorations for multiple prepared teeth was previously presented (Hansen et al., 2009). However, when a prosthodontist is confronted by a full mouth rehabilitation case requiring restorations of individual teeth with crowns, the creation of single provisional restorations may not be practical. Complex situations, such as full mouth rehabilitation, often require cementation, removal, and recementation of provisional restorations several times before the final crowns are delivered. Performing cementation and recementation procedures with six pieces rather than 24 or 28 pieces is more practical for the prosthodontist and the patient; fewer pieces mean lesser time and lower treatment cost.

An additional advantage of the suggested technique is that the provisional restorations may be fitted on two sets of the maxillary and mandibular casts. Normally, clinicians make an impression of the prepared teeth from irreversible hydrocolloid impression materials that may be poured only once (Gratton and Aquilino, 2004; Vahidi, 1987). This procedure does not allow the opportunity for proper trimming, finishing, and final fitting of the provisional restorations on another cast (set of dies) after the completely polymerized provisional restorations are retrieved from the pressure pot. The indirect fabrication of provisional restorations is advantageous because it enhances the accuracy of the margins and reduces the need for intraoral reline (Small, 1999; Crispin et al., 1980). However, when the fully polymerized acrylic is recovered from a cast, the margins typically are not visible to the clinician or technician during the trimming and finishing steps. The main advantage of the proposed technique is that the exact location of the prepared margin is transferred to the completely polymerized acrylic resin, which allows for more accurate trimming and finishing. Intraorally, this process may eliminate the need for the treating clinician to add acrylic or to reline the restorations, as shown in Fig. 5 (note that the clinical photos in Fig. 5 are different from those presented in the manuscript; however, they were fabricated according to the same laboratory procedures described in this report).

Figure 5.

Intraoral views at maximum intercuspation for a full mouth rehabilitation case. The presented indirect laboratory technique had been utilized to fabricate the provisional restorations. It required no further intraoral relining, trimming and/or adjustment at the time of cementation and delivery of provisional restorations. (a) Frontal view. (b) Right lateral view. (c) Left lateral view.

4. Conclusions

Direct techniques for the fabrication of provisional restorations have been limited to single crowns and up to 3- or 4-unit fixed partial dentures (Gratton and Aquilino, 2004; Burns et al., 2003). For full mouth rehabilitation situations, indirect fabrication is considered to be the most suitable technique for the fabrication of provisional restorations. The technique suggested in this report involves indentifying and marking the margin areas accurately on polymerized provisional restorations and splinting them according to sextants of the mouth. This process may eliminate the need for intraoral relining and may facilitate the whole treatment course.

Ethical statement

This laboratory study did not require the approval of the institution’s ethics committee and was prepared in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflict of interest

The author has no financial interests associated with the aforementioned materials used in this study and declares no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

This manuscript was presented in the 62nd annual meeting of the American academy of fixed prosthodontics on April 24–25, 2012, Chicago, USA. (Abstract #27)

References

- Bral M. Periodontal considerations for provisional restorations. Dent. Clinic. North Am. 1989;33(3):457–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns D.R., Beck D.A., Nelson S.K. A review of selected dental literature on contemporary provisional fixed prosthodontic treatment: report of the committee on research in fixed prosthodontics of the academy of fixed prosthodontics. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2003;90(5):474–497. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(03)00259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispin B.J., Watson J.F., Caputo A.A. The marginal accuracy of treatment restorations: a comparative analysis. J. Proshet. Dent. 1980;44(3):283–290. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(80)90012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratton D.G., Aquilino S. Interim restorations. Dent. Clinic. North Am. 2004;48(2):487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen P.A., Sigler E., Husemann R.H. Making multiple predictable single-unit provisional restorations using an indirect technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2009;102(4):260–263. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(09)60167-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman M.G., Takai H., Klokkevold P.R., Carranza F.A. 10th ed. Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2006. Carranza’s Clinical Periodontology. pp. 1050–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Morales W., Mohl N. Restoration of the vertical dimension of occlusion in the severely worn dentition. Dent. Clinic. North Am. 1992;36(3):651–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small B. Indirect provisional restorations. Gen. Dent. 1999;47(2):140–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vahidi F. The provisional restorations. Dent. Clinic. North Am. 1987;31(3):363–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]