Abstract

Screening for subclinical HSV-2 may be a useful adjunct in HIV care. However, HSV-2 serologic tests have been suggested to perform less well in HIV-infected populations. We compared HerpeSelect® HSV-2 ELISA to the Sure-Vue® Rapid HSV-2 Test for HSV-2 screening of sera from 310 HIV-infected persons receiving care at an HIV-dedicated clinic in the Southeastern United States. We determined assay agreement and whether performance of both tests, rather than 1 test alone, would improve screening accuracy. Overall percent test agreement was 96%. Negative percent agreement was best at a HerpeSelect® index value < 0.90 and positive percent agreement was best at a HerpeSelect® index value ≥ 3.0 (97% and 100%, respectively). Using the manufacturer’s established cutoffs for a HerpeSelect® positive versus negative test result discordant results between assays occurred in 4% of cases and the majority of these occurred when the HerpeSelect® index value was between 0.9 and 2.9. These data suggest good correlation between HerpeSelect® and the Sure-Vue® HSV-2 Rapid Test in a U.S. HIV-infected population and suggest that confirmatory testing may not help in HSV-2 diagnosis except in cases where HerpeSelect® index values are between 0.9–3.0.

Keywords: Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2, HIV, HerpeSelect®, Sure-Vue®

INTRODUCTION

Herpes Simplex Virus type 2 (HSV-2) is common in HIV-infected populations with prevalence ranging from 50–95%(1). Because higher rates of HSV-2 shedding occur in HIV/HSV-2 co infected persons and treatment of co infected persons with acyclovir has been shown to reduce both HIV and HSV-2 viral shedding, many experts endorse screening for HSV-2 in HIV-infected populations(2–4). The majority of persons with HSV-2 have subclinical or unrecognized infection(5). Thus, diagnosis depends on the use of HSV-2 specific serologic tests. Several serologic assays are FDA approved for HSV-2 testing in the U.S. The laboratory-based HerpeSelect® HSV-2 IgG is a widely available enzyme linked immunoassay that recognizes antibodies to the HSV-2 specific glycoprotein G2 (gG2) (6). Antibodies to gG2 are highly specific and allow for discrimination between HSV-2 and HSV-1 infection. High sensitivity and specificity are reported for the HerpeSelect® HSV-2 ELISA in various populations(7). However, in African populations, especially HIV-infected African populations, false positive test results are substantially higher than those reported in U.S. populations(8). The Sure-Vue® Rapid HSV-2 Test is another serologic assay based on purified gG2. It allows for direct patient testing of blood from a finger stick as well as laboratory-based testing of patient sera. It also has high sensitivity and specificity but like HerpeSelect®, accuracy of SureVue® may be reduced in HIV-infected populations(8–10). To improve accuracy in HSV-2 screening in both HIV-infected and uninfected populations, some authors suggest screening with HerpeSelect® followed by confirmation with the Sure-Vue® Rapid HSV-2 Test(9, 11). This strategy implies that in cases of a false positive or false negative result that the second HSV-2 test will produce a discordant result leading to further investigation of the patient’s HSV-2 serostatus. Certain populations, such as those with HIV, might be expected to have higher rates of false positives and false negatives since immune dysregulation may alter the reactivity of sera from HIV-infected patients with the assays’ substrates, a phenomenon observed with other serologic tests in HIV-infected populations(12, 13).

In this study, we compared HerpeSelect® ELISA to the Sure-Vue® Rapid HSV-2 test in an HIV-infected population attending an urban U.S. HIV clinic. Our goal was to determine test agreement and disagreement between HerpeSelect® and SureVue® to understand the potential utility of performing 1 versus both tests for screening in the HIV clinical setting.

METHODS

Study Population

Patients without a history of ano-genital herpes receiving care at a dedicated HIV clinic in Birmingham, Alabama were approached for HSV-2 screening between July 2009 and May of 2011. Medical record review followed by direct patient interview was used to identify persons without a history of genital herpes. To reduce the potential influence of immunosuppression on test performance, only patients with a CD4 count of ≥250 cells/mm3 during the preceding 6 months were eligible for study participation. Clinic patients meeting these criteria were approached at regularly scheduled, HIV follow-up appointments. Subjects provided written informed consent for participation. A total of 403 patients were approached to participate, of which 93 declined. The most common reason for declining HSV-2 serologic testing was distance from the primary study site since HSV-2 screening was part of an ongoing study requiring multiple study visits. The remainder declined due to busy schedules or no desire to know their HSV-2 status. Blood was drawn and appropriately stored at −80°C until serologic testing. This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board.

HSV-2 Serologic Testing and Western Blot

Focus Diagnostics HerpeSelect® HSV-2 ELISA IgG (Cypress, CA) and the Sure-Vue® Rapid HSV-2 Test (Fischer Scientific, previously named the POCkit) were used to screen for HSV-2 antibodies. Both are serologic tests that recognize the HSV-2 specific protein gG2. HerpeSelect® HSV-2 ELISA IgG was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The average index value from 2 separate assays is presented. The Sure-Vue® Rapid HSV-2 Test was performed on the same day for each serum sample according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Per the manufacturer’s recommendation, the Sure-Vue® Rapid HSV-2 Test was reported as positive when the test spot was clearly colored red or pink. The test was reported as negative when there was no spot or only a very faint spot. HSV-2 type specific western blot was performed on sera with discordant results at the University of Washington as previously described(14). Western blot readers were blinded to the results of the HerpeSelect-2® HSV-2 ELISA and Sure-Vue® Rapid HSV-2 test results.

Collection of Patient Data

At the time of HSV-2 screening, basic demographic information was collected for each participant. In most cases, CD4 lymphocyte count/mm3 and HIV viral copy number/μl were performed on the same day that sera were collected for HSV-2 serologic screening. CD4 lymphocyte count/mm3 and HIV copy number/μl were performed by the University of Alabama Hospital laboratory and reported in the electronic medical record. When not available on the same day, CD4 lymphocyte count/mm3 and HIV copy number/μl obtained closest to the date on which sera was collected for HSV-2 screening were used (±90 days from the date of HSV-2 screening).

Statistical Analysis

To compare HerpeSelect® results to the Sure-Vue® results, the estimate of agreement was calculated. The overall test agreement was determined through summation of samples in which there was agreement for both positive and negative results between tests divided by the total number of samples. To differentiate agreement for positive and negative results, we also calculated the positive percent agreement and the negative percent agreement. This method was chosen because it allows comparison of tests in which neither is established as the reference standard(15, 16). Percent agreement and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the Fisher’s Exact mid-P method.

RESULTS

A total of 310 HIV-infected patients denying a history of genital herpes were screened for HSV-2. The study population characteristics are presented in Table 1. Consistent with the demographic characteristics of the clinic, the majority of participants were male, Caucasian, and had a median age of 43. HIV-related variables were available for 308/310 participants. Almost all participants (97%; 300/308) were prescribed ART with 72% (221/308) having an undetectable viral load and 88% (207/308) having a viral load of <500 copies/μl. Median CD4 lymphocyte count was 563 cells/mm3. While inclusion criteria required that all participants have a CD4 lymphocyte count ≥250 cells/mm3 during the 6 months preceding HSV-2 screening, on the date that HSV-2 serologies were obtained, 11 had CD4 counts ≤250 cells/mm3.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics and HSV-2 results*

| Gender** | |

| Male | 260 (84) |

| Female | 48 (16) |

| Race** | |

| African American | 132 (43) |

| Caucasian | 174 (57) |

| Other | 2 (<1) |

| Age*** | 43 (19–72) |

| Prescribed antiretroviral therapy** | 300 (97) |

| CD4 count/mm3*** | |

| Absolute | 563 (116–1603) |

| Percent | 30 (10–59) |

| HIV copies/μl** | |

| <50 copies | 221 (72) |

| <500 copies | 270 (88) |

| HSV-2 Positive by HerpeSelect®*# | 189 (61) |

| HSV-2Positive by Sure-Vue®* | 187 (60) |

N = 308 Demographic and HIV-related data missing for 2 participants. Serologic tests performed on sera from all 310 participants.

N (%)

Median (Range)

Using the package insert’s cutoffs

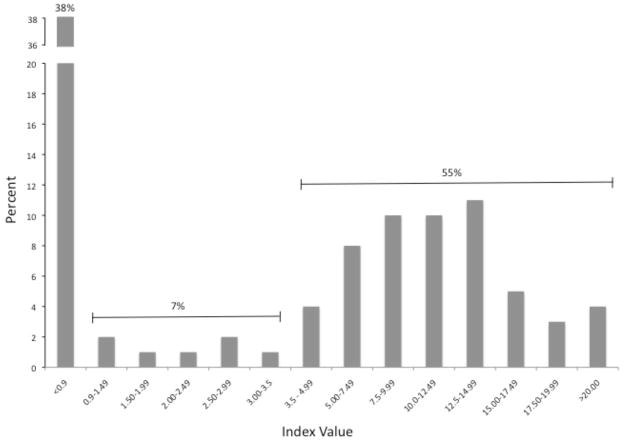

HerpeSelect® ELISA was performed per the manufacturer’s package insert. Index values in the study population ranged from 0 to 27.66. The percent of samples per index value range is presented in Figure 1. Overall, there was a bimodal distribution with most index values <0.9 or >3.5. Only 7% (22/310) of index values by HerpeSelect® were ≥0.9 and ≤3.5. Using the manufacturer’s recommended cutoffs, 61% (189/310) and 60% (187/310) of the study population was HSV-2 positive by HerpeSelect® and Sure-Vue®, respectively (Table 1). To determine test agreement between these 2 tests, we compared the Sure-Vue® results to increasing HerpeSelect® index value cut-offs. An index value of 0.9 was used as the initial cut-off for a negative readout. Incrementally increasing index values to a maximum value of ≥3.5 were then compared to the Sure-Vue® result. As demonstrated in Table 2, the overall percent agreement was 95–96% between the two tests, regardless of the HerpeSelect® index value designated as the cutoff between a positive and negative test result. However, the optimal negative percent agreement occurred at an index value of 0.9 (97%; 95% CI: 93.2 – 99.4) and the optimal positive percent agreement occurred at an index value of ≥ 3.0 (100%; 95% CI: 98.3–100).

Figure 1.

Sera from 310 HIV-infected participants were analyzed by HerpeSelect®. The average of 2 tests were calculated and presented above as the percent (Y-axis) of sera with index values within each range (X-axis).

Table 2.

Percent agreement between HerpeSelect® and Sure-Vue® HSV-2 serologic tests using increasing index value cutoffs for a negative and positive test result*

| HerpeSelect® Index Value | Overall Percent Agreement | Negative Percent Agreement | Positive Percent Agreement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.9 | 96.1 (93.5–97.9) | 97.5 (93.2 – 99.4) | 95.3 (91.6–97.7) |

| 1.5 | 96.1 (93.5–97.9) | 95.9 (91.2–98.5) | 97.3 (92.7 – 98.4) |

| 2.0 | 96.1 (93.5–97.9) | 94.4 (89.3–97.5) | 97.3 (94.1–99.0) |

| 2.5 | 96.1 (93.5–97.9) | 93.1 (87.7–96.6) | 98.3 (95.5 – 99.6) |

| 3.0 | 96.1 (93.5–97.9) | 91.2 (85.5–95.1) | 100 (98.3 – 100.0) |

Data presented as Percent (95% Confidence Intervals).

When using the manufacturer’s recommended HerpeSelect® index value interpretation of <0.9 as negative, ≥0.9 to <1.1 as indeterminate and ≥1.1 as positive and comparing results to the Sure-Vue® HSV-2 Rapid test readout, 4% (13/310) of sera gave discordant test results. Two samples fell in the range defined by the manufacturer of HerpeSelect® as indeterminate (index value between 0.9 and 1.1) (Table 3). All discordance between tests occurred when the HerpeSelect® index value was < 2.9, and 77% occurred between 0.9 and 2.9. To further evaluate the 13 specimens with discordant HerpeSelect®/Sure-Vue® test results, western blot was performed at the University of Washington. Western blot more often agreed with the HerpeSelect® result than with the Sure-Vue® result (6 of 9 versus 3 of 9). In 4 other samples with discordant results, western blot was unable to provide a definitive result. In addition to HSV-2 serologic results, patient characteristics in cases of test discordance are presented in Table 3. Caucasian men demonstrated a high prevalence of discordance between tests. In addition, atypical western blot results (i.e. banding pattern partially but incompletely characteristic of infection), may represent early infection (17). However, size of the population with discordant results limits analysis for any statistical relationship between patient characteristics and test discordance.

Table 3.

Characteristics and western blot results from patients with discordant HSV-2 results

| Sera # | HerpeSelect® Index Value | HerpeSelect® Interpretation | Sure-Vue® HSV-2 | Western Blot | Patient Age | Patient Race | Patient Gender | Patient HIV viral load | Patient CD4 count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.026 | N | P | A | 55 | C | M | 49 | 914 |

| 2 | 0.579 | N | P | A | 56 | C | M | <48 | 689 |

| 3 | 0.747 | N | P | P | 63 | C | F | 58 | 292 |

| 4 | 0.990 | I | N | N | 40 | C | M | 745 | 671 |

| 5 | 1.047 | I | P | A | 43 | C | M | <48 | 699 |

| 6 | 1.142 | P | N | A | 44 | C | M | <48 | 929 |

| 7 | 1.295 | P | N | P | 37 | C | M | <48 | 205 |

| 8 | 1.968 | P | N | N | 30 | C | M | <48 | 515 |

| 9 | 2.178 | P | N | P | 30 | C | M | 3,328 | 402 |

| 10 | 2.500 | P | N | P | 45 | AA | M | <48 | 340 |

| 11 | 2.572 | P | N | P | 59 | C | M | <48 | 607 |

| 12 | 2.670 | P | N | P | 34 | C | M | <48 | 1,163 |

| 13 | 2.837 | P | N | P | 60 | C | M | 10,800 | 1,151 |

N = Negative, P = Positive, I = Indeterminate, A = Atypical (may represent early seroconversion)(17).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine test agreement between HerpeSelect® HSV-2 ELISA and the Sure-Vue® HSV-2 Rapid Test to better understand the utility of confirmatory testing for HSV-2 screening in a U.S. HIV-infected population. Overall, test agreement between the HerpeSelect® HSV-2 assay and the Sure-Vue® HSV-2 Rapid Test was high (96%). Negative percent agreement between tests was best at HerpeSelect® index values < 0.90 and positive percent agreement was best at HerpeSelect® index values ≥ 3.0 (97% and 100%, respectively). Most cases of discordance between tests occurred in a narrow range of HerpeSelect® index values including the manufacturer’s designated equivocal range of 0.9–1.1 as well as the range of 1.1–3.0. Taken together, these data suggest that in our population, confirmation of HerpeSelect® with a second serologic test may offer little benefit. However, in cases in which HerpeSelect® index values fall between 0.9–3.0, confirmation testing may identify samples in need of further analysis. For HIV-infected persons in the U.S., a screening algorithm that focuses confirmation testing to only a small subset of HerpeSelect® index values may represent a strategy to ensure accuracy while minimizing overall cost in the clinical setting.

In our HIV-infected population, HerpeSelect® index values fell into a bimodal distribution with the majority <0.9 or >3.5 and only 7% of sera falling into a range of ≥0.9 to ≤3.5 (Figure 1). Of note, this pattern mirrors our experience with HerpeSelect® in an HIV-uninfected geographically and racially/ethnically similar population (7.3% of index values ranged from ≥0.9 to ≤3.5; data no shown). In contrast to data from sub-Saharan Africa, these data suggest similar performance of HerpeSelect® in HIV-infected and uninfected persons and support previous research supporting the superior performance of HerpeSelect® in U.S and European populations when compared to African populations(8). The reduced performance of HerpeSelect® HSV-2 ELISA in sub-Saharan Africa may result from operator error, genetic variation in African compared to U.S. populations, inappropriate specimen storage or processing, or cross-reactivity of sera due to unidentified infections more common in sub-Saharan Africa (8, 10, 17). Specific to HIV, our study included mostly participants on ART with well-controlled HIV and stable CD4 lymphocyte counts. Thus, our population might be considered potentially more immune competent than HIV-infected populations screened in other studies including those performed in sub-Saharan Africa. With a median CD4 lymphocyte count of 532 cells/mm3, our results may not apply to HIV-infected persons with lower CD4 lymphocyte counts. Further work is needed to determine how immune status as reflected by CD4 lymphocyte count might influence HerpeSelect® test accuracy and test agreement with Sure-Vue® or other HSV-2 confirmatory tests.

The best approach to making an accurate HSV-2 diagnosis when HerpeSelect® index values fall between 0.9 and 3.5 remains unclear. In this study, of sera with index values in this range there was only 50% agreement with SureVue®. HSV-2 specific western blot was performed on sera with discordant results and provided a definitive diagnosis in 9 of 13 cases. Although western blot remains the reference standard in HSV-2 serologic testing, it is relatively expensive and inaccessible to most clinical settings. A more reasonable option for sera with test values in this range may be to repeat HSV-2 screening at a later date as currently recommended for HerpeSelect® HSV-2 ELISA index values in the equivocal range of 0.9 to 1.1. Broadening the range to include index values up to 3.0 may help to clarify serostatus in cases of early seroconversion, artifact, or lab error. Yet clinically practical diagnostic strategies for patients with sera remaining in this range on repeat testing are needed.

We acknowledge the limitations of this study. The study included a geographically narrow population. Comparison to the reference standard western blot was not performed on sera in which there was agreement between HerpeSelect® and Sure-Vue®. This means that we may have misclassified a proportion of dually false negative or false positive sera. Furthermore, both assays measure antibodies to gG2 and might be expected to give concordant results even in cases of false positive or false negative results. However, based on the recently published work of Lingappa et al, we expect true negative and true positive rates to be high in cases of test agreement(9). We did not include HIV-infected participants with very low CD4 counts. Further analysis of HerpeSelect® performance based on CD4 count is an important next step in operationalizing its use in this clinical setting.

Based on our findings, there may be limited utility to confirmation testing of HerpeSelect® with the SureVue® Rapid HSV-2 test in HIV infected U.S. populations in most cases. However, HerpeSelect® index values between 0.9 and 3.0 remain suspect and warrant further investigation to establish the patient’s HSV-2 status.

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This work was supported by GlaxoSmithKline. N.J. Van Wagoner was supported in part by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Infectious Diseases Training Grant (T32 – A152069-07).

ABBREVIATIONS

- HSV-2

Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- gG2

glycoprotein G2

- Ig

Immunoglobulin

- N

Negative

- P

Positive

- I

Indeterminate

- A

Atypical

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Van Wagoner, Dr. Lee, and Ms. Dixon have no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Hook has received research support and honoraria from Becton Dickinson. Dr. Morrow’s laboratory has received grants for laboratory testing, consulting fees, or honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, Roche Diagnostics and DiaSorin over the past 3 years.

References

- 1.Gupta R, Warren T, Wald A. Genital herpes. Lancet. 2007 Dec 22;370(9605):2127–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61908-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strick LB, Wald A, Celum C. Management of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection in HIV type 1-infected persons. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Aug 1;43(3):347–56. doi: 10.1086/505496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guerry SL, Bauer HM, Klausner JD, Branagan B, Kerndt PR, Allen BG, et al. Recommendations for the selective use of herpes simplex virus type 2 serological tests. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Jan 1;40(1):38–45. doi: 10.1086/426438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Workowski KA, Berman S. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010 Dec 17;59(RR-12):1–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu F, Sternberg MR, Kottiri BJ, McQuillan GM, Lee FK, Nahmias AJ, et al. Trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 seroprevalence in the United States. JAMA. 2006 Aug 23;296(8):964–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.8.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wald A, Ashley-Morrow R. Serological testing for herpes simplex virus (HSV)-1 and HSV-2 infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2002 Oct 15;35(Suppl 2):S173–82. doi: 10.1086/342104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashley RL. Performance and use of HSV type-specific serology test kits. Herpes. 2002 Jul;9(2):38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biraro S, Mayaud P, Morrow RA, Grosskurth H, Weiss HA. Performance of commercial herpes simplex virus type-2 antibody tests using serum samples from Sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Dis. 2011 Feb;38(2):140–7. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181f0bafb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lingappa J, Nakku-Joloba E, Magaret A, Friedrich D, Dragavon J, Kambugu F, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of herpes simplex virus-2 serological assays among HIV-infected and uninfected urban Ugandans. Int J STD AIDS. 2010 Sep;21(9):611–6. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.008477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Dyck E, Buve A, Weiss HA, Glynn JR, Brown DW, De Deken B, et al. Performance of commercially available enzyme immunoassays for detection of antibodies against herpes simplex virus type 2 in African populations. J Clin Microbiol. 2004 Jul;42(7):2961–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.7.2961-2965.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrow RA, Friedrich D, Meier A, Corey L. Use of “biokit HSV-2 Rapid Assay” to improve the positive predictive value of Focus HerpeSelect HSV-2 ELISA. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rompalo AM, Cannon RO, Quinn TC, Hook EW., 3rd Association of biologic false-positive reactions for syphilis with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis. 1992 Jun;165(6):1124–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/165.6.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savige JA, Chang L, Horn S, Crowe SM. Anti-nuclear, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic and anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies in HIV-infected individuals. Autoimmunity. 1994;18(3):205–11. doi: 10.3109/08916939409007997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashley RL, Militoni J, Lee F, Nahmias A, Corey L. Comparison of Western blot (immunoblot) and glycoprotein G-specific immunodot enzyme assay for detecting antibodies to herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 in human sera. J Clin Microbiol. 1988 Apr;26(4):662–7. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.4.662-667.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feinstein AR, Cicchetti DV. High agreement but low kappa: I. The problems of two paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(6):543–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90158-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cicchetti DV, Feinstein AR. High agreement but low kappa: II. Resolving the paradoxes. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43(6):551–8. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90159-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gamiel JL, Tobian AA, Laeyendecker OB, Reynolds SJ, Morrow RA, Serwadda D, et al. Improved performance of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays and the effect of human immunodeficiency virus coinfection on the serologic detection of herpes simplex virus type 2 in Rakai, Uganda. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008 May;15(5):888–90. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00453-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]