Abstract

Objectives

This article examines the antecedents and consequences of bullying victimization among a sample of Hispanic high school students. Although cultural and familial variables have been examined as potential risk or protective factors for substance use and depression, previous studies have not examined the role of peer victimization in these processes. We evaluated a conceptual model in which cultural and familial factors influenced the risk of victimization, which in turn influenced the risk of substance use and depression.

Design

Data were collected as part of a longitudinal survey study of 9th and 10th grade Hispanic/Latino students in Southern California (n=1167). The student bodies were at least 70% Hispanic/Latino with a range of socioeconomic characteristics represented. We used linear and logistic regression models to test hypothesized relationships between cultural and familial factors and depression and substance and a meditational model to assess whether bullying victimization mediated these associations.

Results

Acculturative stress and family cohesion were significantly associated with bullying victimization. Family cohesion was associated with depression and substance use. Social support was associated with alcohol use. Acculturative stress was associated with higher depression. The associations between acculturative stress and depression, family cohesion and depression, and family cohesion and cigarette use were mediated by bullying victimization.

Conclusion

These findings provide valuable information to the growing, but still limited, literature about the cultural barriers and strengths that are intrinsic to the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood among Hispanic youth. Our findings are consistent with a mediational model in which cultural/familial factors influence the risk of peer victimization, which in turn influences depressive symptoms and smoking, suggesting the potential positive benefits of school based programs that facilitate the development of coping skills for students experiencing cultural and familial stressors.

Keywords: Hispanic, acculturation, family cohesion, bullying victimization, depression, substance use

Introduction

Violent and/or aggressive peer victimization, especially bullying in schools by other students, has been a significant public health issue for several decades in the United States. (Department of Health and Human Services, 2008). In the 2010 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (CDC, 2010), approximately 32% of high school students reported being bullied during the previous academic year, with girls reporting somewhat higher incidences (17.8% ) than boys (13.3%). Bullying is generally perpetrated by individual students or groups of students against someone they perceive to be weaker and more isolated than themselves (Crick & Grotpeter, 1995). Bullying victimization includes a wide range of behaviors: rumors, exclusion from group play, name-calling, and more direct physical aggression such as hitting, pushing, or shoving (Olweus, 1994). Victimization has been classified into two broad categories: direct and indirect or overt and relational (Bjorkqvist, 1994; Craig, 1998). Direct or overt victimization involves an adolescent being the target of systematic physical aggression perpetrated by peers, such as kicking, slapping, pushing, and verbal harassment. Indirect or relational victimization refers to students becoming the topic of rumors and lies that aim to undermine social relationships and damage reputations.

Students who experience repeated victimization tend to respond with an outward display of distress and often submit to the demands of bullies; some adolescents, if this victimization is persistent, may become more aggressive and hostile themselves (Finkelhor, Ormrod, Turner, & Hamby, 2005) or may experience adverse psychological or physical health consequences. Research has linked peer victimization to a variety of unfavorable health outcomes such as depression, suicidal ideation, other internalizing psychosomatic problems, and risky behaviors such as substance use (Kim, 2005; Klomek, Marrocco, Kleinman, Schonfeld, & Gould, 2008; Ramya & Kulkarni, 2010; Reijntjes et al., 2011; Seals & Young, 2003; Weiner, Sussman, Sun, & Dent, 2005). However, the antecedents and consequences of peer victimization have not been sufficiently studied in immigrant and/or minority student populations (Swendsen & Merikangas, 2000; Luk, Wang, & B. G. Simons-Morton, 2010; Tharp-Taylor, Haviland, & D’Amico, 2009). It is important to understand the relationship between peer victimization and unfavorable health outcomes for adolescents from diverse backgrounds in order to develop effective and appropriate interventions that can decrease the sequelae of bullying victimization.

Bullying and victimization among Hispanic adolescents

Bullying occurs within a specific sociocultural context. The increasing ethnic diversity in much of the United States, especially in western states, has produced rapid demographic shifts that create a unique set of conditions impacting rates of victimization and perpetration, influencing resource distribution, and informing coping styles. In the western United States, Hispanics are the largest and most rapidly growing minority group. Between 2000 and 2010, the Hispanic population grew by 43 percent—four times the growth in the total population. Forty-one percent of Hispanic Americans live in Western States, where Hispanics account for 29% of the population, as compared with 16% nationally (US Census Bureau 2010).

Ethnicity and acculturation play a central role in health-related behaviors and overall health outcomes of adolescents (Graham, 2000; Bauman & Summers, 2009; Unger et al., 2006). Cultural orientation refers to an individuals understanding of his or her own cultural self-definition while acculturation refers to changes in practices, values, and identification that occurs as a result of contact with multiple cultures (Schwartz, Montgomery,& Briones, 2006; Schwartz, Zamboanga, Rodr guez & Wang, 2007). This process is bi-dimensional and occurs as individuals adapt to life within a dominant culture while concomitantly balancing the conflicting cultural practices and perspectives of their family, country of origin, and host culture (Berry, 1998; Schwartz et al., 2010). Acculturative stress (stress that occurs as a result of the acculturation process) has been linked to an increase in feelings of isolation and anxiety that in turn can lead to an increase in substance use and aggression (Finch et al., 2001; Le & Stockdale, 2008; Schwartz et al., 2007). Some studies have reported that compared with non-Hispanic whites, Hispanic students are more likely to report being in fights, being injured in a fight, and being threatened with a weapon at school (Kaufman et al., 2001;Youth Risk Behavior Survey, 2010). However, other studies have found no significant differences between Latino and non-Latino youth in levels of either victimization or perpetration of violence and/or bullying (Bacallao & Smokowski, 2007; Bird et al., 2006). Too few have focused on the relationships among sociocultural factors, victimization, and negative health outcomes among Hispanic adolescents.

Theoretical perspectives

Ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979) posits that the development of a child occurs within five systems and involves the relationships and events that occur within them. These systems include the microsystem (family, school, neighborhood) mesosystem (relationships that connect the microsystems), exosystem (larger social system), macrosystem (cultural norms, laws,) and chronosystem (time continuum). The personal resources, exchanges, and conflict that take place in one domain will affect functioning within other domains as well. Within this dynamic, the psychological and tangible assets that are provided to a child in one system will influence how a child meets the demands and challenges of his/her role in another (Voydanoff, 2004). The relationships within the microsystem are the most proximal and interactive and therefore exert the strongest influence on psychosocial development and behavior.

From a developmental and cultural perspective, the family factors associated with the acculturation process are also linked to behavioral and health outcomes. It is highly probable that adolescents’ reactions to bullying and the development or presence of coping skills are influenced by family practices and beliefs. Family cohesion, the emotional bonding and support among family members, has been shown to protect adolescents from psychological distress, substance use, and violence (Olson, Russell, & Sprenkle, 1982; Hovey & King, 1996). Among Hispanic immigrant families, cohesion can decrease with acculturation to the U.S. culture and/or loss of Hispanic cultural values such as familism (Vega, 1990; Hill, Bush, & Roosa, 2003). Acculturative stress may have several sources and can arise as a result of the discrepant rate and directions between parent and child acculturation, language conflict, and cultural incompatibilities (Gil & Vega, 1998 Szapocnik, 1988).

To what degree children develop the ability to maximize their own potential and achieve positive health outcomes is contingent upon the various environments in which they interact. When examining bullying victimization from an ecological systems approach, individual characteristics, influential relationships, family and school environments, and societal norms all may contribute to increase or decrease the risk of victimization

Cultural orientation has been linked to health compromising and health promoting behaviors such as substance use, risky sexual behavior, violence/violence victimization, and depression (De La Rosa, M., 2002; Bethel & Schenker, 2005; Gonzales et al, 2006; Unger et al, 2006; Smokowski & Bacallo, 2006; Afable-Munsuz & Brindia, 2006; Szapocnik et al., 2007; Afable-Munsuz & Brindia, 2006). Although research has shown that immigrant populations experience a variety of stressors that may play an important role in health behavior and health outcomes, to date results have been inconclusive in establishing direct links between specific risk factors and outcomes. Several studies have concluded that orientation to the US culture and/or loss of the culture of origin is a risk factor for violence perpetration and victimization and substance use, whereas others have found that indicators of low integration into the US culture, such as acculturative stress and language difficulties are risk factors for experiencing interpersonal violence (Bureil et al., 1982; DHHS, 2009; Sommers et al., 1993; Vega et al., 1995; Luk, Wang, & Simons-Morton, 2010).

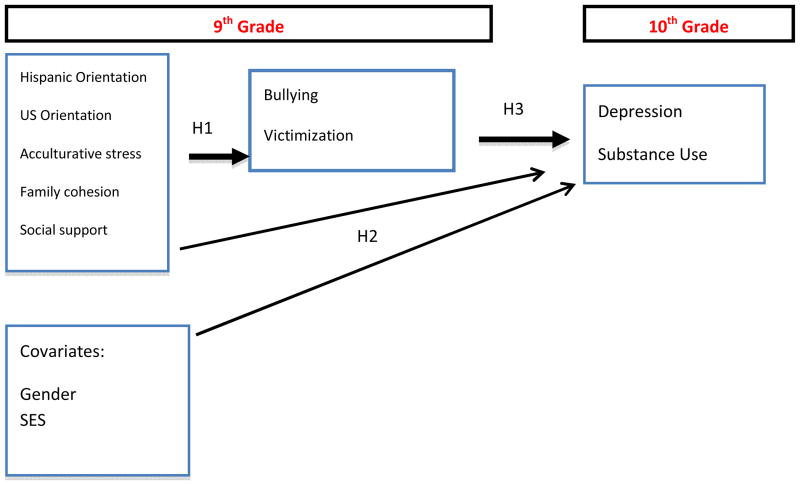

This article examines the antecedents and consequences of victimization among a sample of Hispanic students in Los Angeles, California, who completed surveys in 9th and 10th grade. We evaluated a conceptual model (shown in Figure 1) in which cultural and familial factors influenced the risk of victimization, which in turn influenced the risk of substance use and depression. The specific hypotheses were the following:

Figure 1.

Hypothesized Mediating Model

-

H1

Cultural and familial factors in 9th grade will be associated with vulnerability towards victimization in 9th grade:

-

We anticipated that acculturative stress would be associated with higher levels of victimization (H1a) while greater family cohesion and social support would predict lower levels of victimization (H1b,c).

We also theorized that cultural orientation would be associated with peer victimization (H1d) although we did not hypothesize the direction of association for either US or Hispanic-Latino orientation due to limited research on this subject within a population of Hispanic students attending a predominately Hispanic school.

-

-

H2

Cultural and familial factors in 9th grade will predict substance use and depression in 10th grade.

-

We expected that higher acculturative stress would be associated with higher levels of both substance use and depression and that (H2a) higher family cohesion (H2b) and social support (H2c) would be associated with lower levels of substance use and depression.

We hypothesized that cultural orientation would be associated with substance use and depression (H2d). Again, due to inconclusive findings in the literature, we did not hypothesize about the direction of the associations between cultural orientation (US orientation and Hispanic-Latino orientation) and depression or substance use outcomes.

-

-

H3

Bullying victimization will be associated with increased substance use and depression.

-

H4

Bullying victimization will mediate the associations between cultural/familial variables and both substance use and depression.

Methods

Data were collected as part of Project RED (Reteniendo y Entendiendo Diversidad para Salud), a three-year longitudinal study of the role of acculturation patterns and substance use among Hispanic/Latino students in Southern California. Data from the first and second year of collection, in Fall 2005 and 2006 respectively, were used for the current analysis. A detailed description of data collection procedures is provided elsewhere (Unger, Ritt-Olson, Wagner, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2007).

Participants were initially enrolled when they were in the 9th grade. They were recruited from seven public high schools in the Los Angeles school district. The schools included in our study had a student body of at least 70% Hispanic/Latino as reported by the California Board of Education. The overall sampling strategy was designed to sample schools with a wide range of socioeconomic characteristics: the range of median household incomes in the zip codes within the schools selected was $29,000 and $73,000 according to the US Census data. In 2005 all 9th grade students in the schools were invited to participate in the survey if they provided written or verbal parental consent and student assent. The University of Southern California Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

A total of 3,218 students were invited to participate. Of those, 2,420 (75%) provided parental consent and student assent. Of the 2,222 students who completed the 9th grade survey (92%), 1,963 (88%) self-identified as Hispanic or Latino or reported a Latin American country of origin. Their countries of origin included Mexico (84%), the United States (29%), El Salvador (9%), Guatemala (6%), and Honduras (1%); respondents could select more than one country of origin. Of the 1,963 Hispanic/Latino students, 1,708 (87%) completed surveys again in 10th grade. We eliminated 532 who had missing or incomplete data on variables used in this analysis. We excluded students who did not have survey data for year 2 and/or did not provide responses on bullying victimization (287) or depression measures (180). We retained 1,167 who identified themselves as Hispanic or Hispanic-mixed descent and provided responses on all survey items of interest. Our analytic sample did not vary from those lost to attrition on acculturative stress (p=0.64), family cohesion (p=0.67), SES (p=.75), gender (p =.09), or Hispanic-Latino orientation (p=.64). The analytic sample had a slightly lower rate of bullying victimization (p=.02), US orientation (p=.025), and was slightly higher in depressive symptoms ( p = .0319). It did not differ in alcohol use (p= .0749) marijuana use (p=.9902), or cigarette use (p = .6745). Substance use outcomes were examined with chi-square, depression with t-test.

Measures

Demographics

Gender was measured using a single self-report item. Ethnicity was assessed with one question that asked participants to “choose all those that apply” from a list of 15 possible ethnic identifications. Any endorsement of Hispanic/Latino or Hispanic-mixed was considered as Hispanic. SES was assessed using the ratio of rooms in the home to the number of individuals living in the house (Myers, Baer & Choi, 1996).

Cultural orientation

was measured with a brief version of the Acculturation Rating Scale for Mexican-Americans-II (Cuellar, Arnold & Gonzales, 1995). The ARSMA-II is a widely used measure designed for use with Mexican Americans but has also been used with other Hispanic/Latino groups. The ARSMA-II assesses the extent to which individuals are oriented toward the US culture, the Hispanic culture, or both cultures. Items assess language use and preference, ethnic identity, cultural heritage and ethnic interaction. Cronbach’s alphas in this sample were .81 for the US orientation scale and .72 for the Hispanic orientation scale.

Family cohesion

(Cronbach’s alpha = 0.79) was assessed with 11 items, including “Family members feel very close to each other.” “In our family, everyone shares responsibility.” “Family members like to spend their free time with each other.” “Family members go along with what the family decides to do.” Responses were reported on a scale from Almost Never (1) to Almost Always (5). These items were selected from the FACES-II scale (Olson, Portner, & Bell, 1982), because they had the highest factor loadings and best psychometric properties in a similar sample of adolescents who were enrolled in the pilot for the current study.

Acculturative stress

(Cronbach’s alpha = 0.67) Participants responded to a modified version of the Acculturative Stress Scale (Gil & Vega, 1993). The items selected for our study consisted of questions that focused on overall cultural strain and parent-child discrepancies. The questions asked, “How often do you….” “Feel uncomfortable when you have to choose between doing things like Americans or non-Americans?” “Have problems with your family because you like to do things the American way?” “Get upset with your parents because they don’t understand the American lifestyle?” Response options ranged from Never (1) to Very Often (4).

Social support

(Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90) Social support was assessed using the Zimet, Dahlem, Zimet & Farley Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (1988). This instrument is a twelve-item measure with ratings made on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4).

Bullying victimization

(Cronbach’s alpha = 0.64) Bullying victimization was measured by averaging responses to self-reported frequency of events in the past 12 months. These items are part of the California Healthy Kids Survey (California Department of Education, 2006), the largest statewide survey of resiliency, protective factors, and risk behaviors among adolescents. Direct and indirect victimization was assessed using a subset of this questionnaire distinguishing between physical and nonphysical forms of harassment. Questions about indirect/verbal victimization included, “During the past 12 months how many times have mean rumors or lies been spread about you?” and “How many times have you been made fun of because of your looks or the way that you talk?” Questions about direct/physical victimization included how many times respondents had been shoved, hit, or threatened because of their race, ethnicity, religion or gender over the last 12 months while on at school. Response options ranged from 0 times to 4 or more times.

Substance use

The outcomes of interest in the current analyses were current substance use and depressive symptoms. Substance use items included past 30-day use of alcohol, cigarettes, and marijuana, and were based on items used in the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2005). Survey items were multiple-choice, but due to skewed distribution, the variables were dichotomized as used in the past 30 days or have not used in the past 30 days. Each of the three substances was used as a separate outcome variable.

Depressive symptoms

(Cronbach’s Alpha =0.89) Depressive symptomatology was measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a reliable and validated self-report measure (Radloff, 1977). A continuous composite score of all items on the CES-D was calculated and used in analyses.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables used in analyses. All continuous variables were standardized to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1. To evaluate H1, we conducted a linear multiple regression analysis with acculturative stress, family cohesion, cultural orientation and social support as the predictor variables and victimization as the outcome variable. To evaluate H2, we conducted regression analyses with acculturative stress, family cohesion, cultural orientation, and social support in 9th grade as the predictor variables and substance use (logistic regression models) and depression (linear regression model) as the outcome variables in 10th grade. To evaluate H3, we conducted regression analyses with victimization in 9th grade as the predictor variable and substance use (logistic regression models) and depression (linear regression model) in 10th grade as the outcome variables. To assess mediation, (H4), we followed the criteria set by Baron and Kenny (Baron & Kenny, 1986). We ran separate regression analyses for acculturative stress, family cohesion, cultural orientation, and social support predicting depression and these factors predicting substance use and depression while controlling for peer victimization. We used the PRODCLIN program (MacKinnon, D.P., Fritz, M.S., Williams, J., & Lockwood, C.M., 2007) to determine the significance of the mediated effect. A Sobel test was done to obtain the test statistic (Preacher & Leonardelli, 2010). All of these linear and logistic models controlled for gender, SES and clustering in schools. SAS PROC GLIMMIX was used for regression analyses.

Results

Descriptive statistics for demographic characteristics and variables of interest are presented in Table 1. Our study sample was 53.8% female and 46.2 % male with 88.9% indicating that they were born in the US. Eighty six percent of participants were 14 years old with approximately 8% between 12 and 13 and 6% between 15 and 16 years old. Nearly 30% of respondents stated they spoke either only or mostly English at home, 55% spoke English and another language and 16% indicated that they spoke mostly or only another language. When amongst their friends, over seventy percent of students spoke English or mostly English, 27% spoke English and another language and less than 2% spoke only or mostly another language.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Mean (SD)/ % | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics: | ||

| Age | 13.99 (.38) | |

| Gender | Male = 46.2% | __ |

| Female = 53.8% | ||

| Birth Country | United States = 88.9% | __ |

| Other = 11.1% | ||

| Language (in Home) | Only English = 12.1% | __ |

| Mostly English = 16.3% | ||

| English/Other equally = 55.7% | ||

| Mostly other language = 12.9% | ||

| Only another language = 3.0% | ||

| Language (w/ Friends) | Only English = 32.8% | __ |

| Mostly English = 38.4% | ||

| English/Other equally = 27.2% | ||

| Mostly other language = 1.4% | ||

| Only another language = 0.3% | ||

| Year one: | ||

| Bullying Victimization | 1.38 (.46) | 1–4 |

| US Orientation | .33 (.29) | 0–1 |

| Hispanic-Latino | .10 (.17) | 0–1 |

| Orientation | ||

| Family Cohesion | 3.52 (.64) | 1.36–5 |

| Social Support | 3.23 (.52) | 1–4 |

| Socioeconomic Status | 1.78 (.88) | .29–7 |

| Acculturative Stress | 1.46 (.57) | 1–4 |

| Year two: | ||

| Depressive symptoms | 1.78 (.54) | 1–3.9 |

| Cigarette use | 8.1 % | |

| Alcohol Use | 86.7% | |

| Marijuana Use | 13.7% | |

Note. N = 1167

H1: Associations between cultural / familial variables and victimization

The results of the linear regression predicting victimization are shown in Table 2. As hypothesized, acculturative stress was associated with higher levels of victimization, and family cohesion was associated with lower levels of victimization. However, social support and cultural orientation were not significantly associated with victimization.

Table 2.

Regression Coefficients for linear regression model predicting bullying victimization

| Predictors | Outcome |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Peer Victimization

|

|

| Standardized Beta | |

| US Orientation | -.05 |

| Hispanic-Latino Orientation | .03 |

| Acculturative Stress | .18*** |

| Family Cohesion | -.12*** |

| Social Support | -.003 |

| SES | .04 |

| Gender | .06 |

Note. All significant findings are in bold.

indicates p <.05,

indicates p <.01, and

indicates p <.001

H2: Associations between cultural / familial variables and substance use and depression

The results of the logistic regression models predicting substance use and the linear regression model predicting depression are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Odds Ratios for models predicting substance use outcomes and linear regression standardized betas for depression

| Predictors | Outcome | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Marijuana | Cigarette | Depression | |||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | Std. beta | ||||

| US Orientation | .84 | .70 | 1.01 | 1.04 | .86 | 1.24 | .93 | .73 | 1.18 | -.01 |

| Hispanic-Latino Orientation | 1.04 | .85 | 1.28 | 1.00 | .83 | 1.21 | 1.21 | .99 | 1.48 | -.02 |

| Acculturative Stress | .86 | .73 | 1.01 | .96 | .80 | 1.14 | 1.08 | .89 | 1.33 | .11*** |

| Family Cohesion | 1.22* | 1.00 | 1.47 | .70** | .58 | .85 | .65*** | .53 | .79 | -.18*** |

| Social Support | 1.24* | 1.01 | 1.51 | .97 | .80 | 1.18 | .91 | .72 | 1.16 | -.001 |

| SES | 1.31* | 1.06 | 1.62 | .89 | .74 | 1.08 | .89 | .70 | 1.13 | .02 |

| Gender | .67* | .46 | .97 | .61** | .43 | .88 | .80 | .51 | 1.25 | .40*** |

Note. All significant findings are in bold.

indicates p <.05,

indicates p <.01, and

indicates p <.001

Substance use

Family cohesion was protective against cigarette and marijuana use, but was a risk factor for alcohol use. Social support was significantly associated with higher alcohol use, but was not associated with cigarette or marijuana use. Girls were significantly less likely to report use of all three substances. Neither cultural orientation nor acculturative stress was significantly associated with substance use.

Depression

As hypothesized, acculturative stress was a risk factor for depression, and family cohesion was protective against depression. Cultural orientation and social support were not significantly associated with depression. Girls, consistent with the extant literature, were more likely to report depressive symptoms than boys.

H3: Associations between victimization and substance use and depression

Cigarette use was significantly associated with bullying victimization (OR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.04, 1.52), as was depression (β = .25, SE = .03, p< .0001). Neither alcohol use (OR=.87, 95% CI = .74, 1.03), nor marijuana use (OR=1.06, 95% CI = .89, 1.26) was significantly associated with bullying victimization.

H4: Mediation

Since acculturative stress was significantly associated with victimization and depression and family cohesion was associated with victimization and substance use, we examined evidence for mediational models involving these variables.

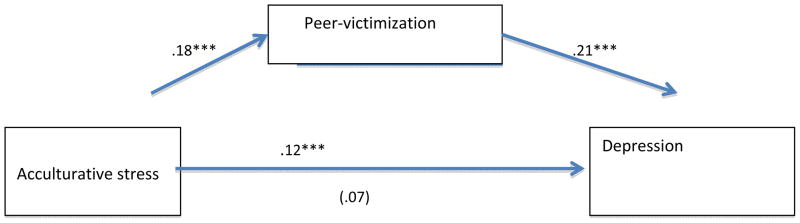

The conditions of mediation were met for our models; acculturative stress and family cohesion were significant predictors of depression and of peer victimization, and peer victimization was a significant predictor of depression while controlling for acculturative stress and family cohesion. Because family is the primary social system in which children learn interpersonal communication techniques and these processes precede victimization in high school, we assumed that bullying victimization would mediate the relationship between family processes and depression or substance use. We used Mackinnon’s asymmetric distribution of products test (McKinnon et al., 2007). This test constructs a 95% CI around the indirect effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable through the mediator, using standard errors calculated with the Sobel formula (Sobel, 1982). If the zero value is not included in the confidence interval it signifies a statistically significant indirect effect and is evidence of partial mediation. As Figure 2 illustrates, the standardized regression coefficient for acculturative stress predicting depression decreased substantially when controlling for bullying victimization (the standardized regression coefficient for acculturative stress predicting depression and controlling for peer victimization and other covariates are in parentheses). The statistical significance of the relationship between acculturative stress and depression disappeared when the association was examined through our mediating variable bullying victimization. Therefore, our statistically significant observed relationship between acculturative stress and bullying in turn predicting depression suggests an important mediational effect of bullying victimization; approximately 58% of the variance in depression attributed to acculturative stress may actually be related to victimization (95% CI = .01-.08, Sobel test statistic =4.88, p < 0.001)). Our model examining the influence of bullying victimization in the association between family cohesion and depression yielded a smaller but significant reduction in the negative in the beta coefficient predicting depression. Nearly 24% of that relationship may be partially due to bullying victimization (95% CI = -.06,-.01, β=-.12, Sobel test statistic = -4.74, p<0.001).

Figure 2.

Mediation Model

Victimization was significantly associated with cigarette smoking, but not with alcohol or marijuana use. Family cohesion, but not the other cultural/family variables, was significantly associated with cigarette smoking. Therefore, a mediation analyses was conducted to determine whether the association between family cohesion and cigarette smoking was mediated by victimization (Figure 2). Again, we found significant partial mediation with nearly 17% of the relationship between family cohesion and smoking explained by bullying victimization (β=-.13, Sobel test statistic =-4.73, p<0.001).

Discussion

Ethnic minority youth may face significant challenges and life stressors, including peer victimization, that place them at high risk for behavioral and psychological problems such as substance use and depression. Although cultural and familial variables such as acculturation, acculturative stress, family cohesion, and social support have been examined as potential risk or protective factors for substance use and depression, previous studies have not examined the role of peer victimization in these processes. Our findings indicate that acculturative stress and family cohesion were associated not only with depression and substance use, but also with peer victimization. Because victimization has also been linked to higher levels of depression and substance use, we examined victimization as a mediator of the associations between cultural/familial variables and substance use and depression. Our findings are consistent with a mediational model in which acculturative stress and lower family cohesion increase the risk of peer victimization, which in turn increases depressive symptoms and smoking. Therefore, it is likely that school based prevention/intervention programs, which are more cost-efficient and feasible than family interventions, can serve important functions. Peer victimization probably occurs exclusively in situations and under conditions present outside the home; therefore efforts on campuses and in the broader community are likely to attenuate the detrimental effects of peer bullying. Some promising areas for school based prevention strategies, to effectively reduce the incidents of peer victimization, are programs that teach negotiation skills to diffuse antagonistic interactions, enhance cross-cultural tolerance and enforce anti-bullying measures. There are interesting preliminary results emerging from research examining how, and if, anti-racist, socially inclusive attitudes and behaviors can be promoted and modeled by students- deemed by peers to be important members of social networks- to shift social norms towards less tolerant attitudes of bullies and harassers on school campuses (Lun, Sinclair, Glenn, & Whitchurch, 2007; Paluck, 2011). Since cultural stressors, family processes and peer interactions all influence the likelihood of bullying victimization, depression and substance use the most beneficial prevention programs should be multi-level approaches. From an ecological perspective these programs would account for cultural stressors alongside strategies that initiate peer norm changes and the development of intrapersonal skills. The design of these comprehensive school based programs, and evaluations of the extent to which they reduce bullying and ethnic prejudices, may substantially advance health promotion efforts for Hispanic adolescents.

Similarly, we found an association between family cohesion, victimization and smoking; although this relationship needs further exploration and may be due to individual and structural factors (not assessed in this study), which could be addressed through education, clinical and policy interventions.

Most of the significant direct effects were in the hypothesized directions. Consistent with previous research, acculturative stress was a risk factor for victimization, and family cohesion was protective against victimization. Peer victimization, acculturative stress, and lower family cohesion were risk factors for depression.

Our findings that family cohesion, a proximal variable, is protective and that more distal variables such as acculturative stress, cultural orientation, and gender norms play influential roles in risk behavior and victimization outcomes are consistent with our ecological theoretical assumption; that the interaction of micro and macro level influences are involved in adolescent health behavior. For this study it appears that family processes may affect a child’s capacity to withstand bullying victimization and integrate with pro-social and protective peers, however, one should be careful to attribute too much to family practices as they are not the sole source of negative outcomes, but rather interact with larger structural and social processes on individual outcomes. We found that peer victimization significantly influences the degree of depressive symptoms after controlling for family cohesion and acculturative stress, suggesting the potential positive benefits of school based programs that facilitate the development of coping skills for students experiencing cultural and familial stressors. However, it should be noted that in addition to developing students’ capacity for healthy adjustment, it also is essential to emphasize the appreciation of diversity among all students to protect immigrant and minority students from being bullied.

Acculturative stress may be an important antecedent to some risk behavior, as it has been linked to isolation and alienation that can impede healthy psychological adjustment as young people transition from adolescence to adulthood (Hovey, 1998; Vega et al., 1995; Hovey & King, 1996). Because adolescence is a critical period of development, it is of considerable importance to better understand the psychological and behavioral manifestations of acculturative stress among ethnic minority adolescents, as well as ways to help them cope with acculturative stress. These findings provide valuable information to the growing, but still limited, literature about the cultural barriers and strengths that are intrinsic to the transition from adolescence to emerging adulthood among Hispanic youth.

However, some unexpected associations emerged. Although victimization, depression, and substance use all comprise a larger class of health compromising outcomes, it is not surprising to find different mechanisms and pathways contributing to their expression. Victimization occurs because of other students’ externalizing behaviors, whereas depression is largely an internal process that can also be affected by external events such as bullying. Substance use is a behavioral manifestation of complex combinations of internal and external factors (e.g., genetic vulnerability, outcome expectancies, availability). Balancing the values and beliefs of two cultures demands significant inter and intrapersonal skill that can be facilitated by the tools and resources that promote resilience and coping. Schools are uniquely positioned to provide these tools and encourage self and other acceptance that can substantially reduce the anxiety and isolation felt by Hispanic youth as they traverse the challenges of adolescence.

Interestingly, higher family cohesion was a risk factor for alcohol use. This finding is consistent with Soto et al. ’s (2011) finding that high levels of familism were predictive of greater alcohol use (Soto et al., 2011). These authors suggest that at large extended family events (which may be quite frequent), where adults use alcohol to celebrate, teen drinking may not be considered dangerous when occurring in the presence of parents and other relatives. It is also conceivable that those students who reported more frequent alcohol use, come from bonded families where drinking is prevalent and acceptable. Future studies using qualitative methods may reveal more about why we found a relationship between family cohesion and alcohol use among these teens.

The multifaceted nature of cultural orientation and bullying victimization poses a complex problem for prevention research. This issue is exacerbated for immigrant youth due to the confluence of familial, social, and cultural factors that increase risk. Moreover, how can prevention programs address the duality of maintaining traditional values and norms while also satisfying the wish/pressure to adapt to more US oriented peers? Secondly, how do these programs address gender differences while also facilitating healthy coping for youth of similar backgrounds with contradictory needs?

In this analysis, US orientation and Hispanic orientation were not significantly associated with substance use. This finding is not consistent with previous studies that have identified US orientation as a risk factor for substance use (Szapocznik et al., 2007:Lau et al., 2005). However, the findings of those previous studies could have been confounded by variables such as acculturative stress, family cohesion, and social support. Previous studies by many of these same researchers have shown that when adolescents are very US-oriented and their parents are not, family functioning worsens. Therefore, including family cohesion, acculturative stress, and social support in our models may have obscured associations between cultural orientation and outcomes that would have been significant had these confounding variables not been included.

Overall these results highlight the importance of proximal level factors and speak to the importance of providing youth with tools that address how to maintain strength of family relationships that are challenged by cultural disparities between children and adults. Our study suggests that Hispanic youth face unique challenges when they navigate two distinct cultures while also considering their own personal identity and behaviors. Practitioners need to consider the ramifications for a child attempting to balance the divergent cultural and gender perceptions of their family, those expressed by peers and those espoused in American society.

Limitations

Several limitations to the present study should be noted. First, the generalizability of our findings is limited to students of predominantly Mexican decent living in urban settings similar to that of Southern California. Second, although our results are consistent with the hypothesized mediational model (acculturative stress increasing the risk of victimization, which in turn increases the risk of depression and substance use), other interpretations are also plausible. For example, it is possible that adolescents who are bullied tend to attribute the bullying to their ethnicity, and therefore perceive higher levels of acculturative stress. It is also possible that depressed adolescents are more likely to be bullied or perceive their levels of acculturative stress to be high. Although the longitudinal data used in this study provide some evidence for temporal precedence, reciprocal causation is certainly plausible.

Interpretations of self-report data should be taken with some caution as responses were not corroborated or verified. Studies relying on self-report data may be biased by participants under or over reporting some behaviors or feelings in an effort to present themselves in ways perceived to be more desirable to researchers, peers, and themselves. While under or over reporting may also be a function of recall and attribution bias, studies that rely on self reports have yielded reliable results (Bradburn, 1983; Rutherford, 2000).

These findings are based on a sample of Hispanic adolescents attending schools that were at least 70% Hispanic necessitating additional research to determine whether these results will generalize to adolescents of other ethnic groups living in other cultural contexts.

Bullying victimization is a growing concern on school campuses nationwide and has long-term consequences particularly in the areas of social functioning and school performance. Because adolescence is a period when identity exploration is extremely salient (Arnett, 2000) future research should clarify how these cultural factors and stressors effect long term social and academic adjustment for Hispanic youth. There is mounting evidence that a one size fits all approach to prevention programming in racially/ethnic diverse communities will be ineffective. Continued research among immigrant youth will provide culturally relevant prevention and treatment information for heterogeneous urban communities.

Key Message.

Our study explores the influences of cultural and familial factors that serve as either risk or protective factors for bullying victimization, depression and substance use. Acculturative stress and low family cohesion were significantly associated with bullying victimization, which in turn mediated the relationship between these factors, depression and tobacco use. School based prevention programs tailored to address these issues and provide students with the necessary skills and resilience to cope with cultural and familial stressors may substantially reduce their vulnerability of peer victimization. Developing cultural tolerance among students and introducing coping skills to address bicultural stress to school based curricula, are a few strategies that may improve Hispanic adolescents’ psychological and social functioning.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grant # DA016310.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest related to the submission of this manuscript.

Works Cited

- Afable-Munsuz A, Brindis CD. Acculturation and the sexual and reproductive health of Latino youth in the United States: a literature review. Perspectives on Sex and Reproductive Health. 2006;38(4):208–19. doi: 10.1363/psrh.38.208.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A period of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacallao ML, Smokowski PR. The Costs of Getting Ahead: Mexican Family System Changes After Immigration. Family Relations. 2007;54(1):52–66. [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman S, Summers J. Peer Victimization and Depressive Symptoms in Mexican American Middle School Students: Including Acculturation as a Variable. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2009;13(4) [Google Scholar]

- Bethel JW, Schenker MB. Acculturation and smoking patterns among Hispanics: a review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;29(2):143–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird H, Davies M, Duarte CS, Shen S, Loeber R, Canino GJ. A Study of Disruptive Behavior Disorders in Puerto Rican Youth: II. Baseline Prevalence, Comorbidity, and Correlates in Two Sites. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(9):1042–1053. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000227879.65651.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkqvist K, et al. Sex differences in covert aggression among adults. Journal of Aggressive Behavior. 1994;20(1):27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- The California Healthy Kids Survey(CHKS) California Department of Education. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance Survey, youth online: Comprehensive results. 2010 Retrieved from http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/yrbss/

- Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development. 1995;66(3):710–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Rosa M. Acculturation and Latino adolescents’ substance use: a research agenda for the future. Substance Use and Misuse. 2002;37 (4):429–56. doi: 10.1081/ja-120002804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch BK, Hummer AH, Kol B, Vega WA. The Role of Discrimination and Acculturative Stress in the Physical Health of Mexican-Origin Adults. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2001;23 (4):399–429. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, Hamby SL. The victimization of children and youth: a comprehensive, national survey. Child Maltreatment. 2005;10(1):5–25. doi: 10.1177/1077559504271287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick KM, Dulin A, Piko B. Bullying and Depressive Symptomatology Among Low-Income, African–American Youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;39(6):634–645. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming LC, Jacobsen KH. Bullying and symptoms of depression in chilean middle school students. The Journal of School Health. 2009;79(3):130–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.0397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill NE, Bush KR, Roosa WM. Parenting and Family Socialization Strategies and Children’s Mental Health: Low–Income Mexican–American and Euro–American Mothers and Children. Child Development. 2003;74(1):189–204. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey JD, King CA. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation among immigrant and second-generation Latino adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:1183–1192. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199609000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey JD, King Ca. Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation among Mexican American adolescents: Implications for the development of suicide prevention programs in schools. Psychological Reports. 1998;83:249–250. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.83.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YS. School Bullying and Suicidal Risk in Korean Middle School Students. PEDIATRICS. 2005;115(2):357–363. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klomek AB, Marrocco F, Kleinman M, Schonfeld IS, Gould MS. Peer victimization, depression, and suicidiality in adolescents. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38(2):166–180. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, McCabe KM, Yeh M, Garland AF, Wood PA, Hough RL. The acculturation gap-distress hypothesis among high-risk Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2005;19:367–375. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Thao N, Stockdale Gary. Acculturative dissonance, ethnic identity, and youth violence. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14 (1):1–9. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk JW, Wang J, Simons-Morton BG. Bullying Victimization and Substance Use Among U.S. Adolescents: Mediation by Depression. Prevention Science. 2010;11(4):355–359. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0179-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lun J, Sinclair S, Glenn C, Whitchurch E. (Why) do I think what you think? Epistemic social tuning and implicit prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:957–972. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fritz MS, Williams J, Lockwood CM. Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods. 2007;39:384–389. doi: 10.3758/bf03193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers D, Baer WC, Choi SY. The changing problem of overcrowded housing. Journal of the American Planning Association. 1996;62:66–84. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil KA, Conner BT, Kendall PC. Internalizing disorders and substance use disorders in youth: Comorbidity, risk, temporal order, and implications for intervention. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011;31(1):104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson DH, Russell CS, Sprenkle DH. Circumplex model of marital and family systems: VI. Theoretical update. Family Process. 1983;22:69–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1983.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palluck LP. Peer pressure against prejudice: A high school field experiment examining social network change. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2011;(47):350–358. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus D. Bullying at school: Basic facts and an effective intervention programme. Promotion & Education. 1994;1(4):27–31. 48. doi: 10.1177/102538239400100414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramya SG, Kulkarni ML. Bullying Among School Children: Prevalence and Association with Common Symptoms in Childhood. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2010;78(3):307–310. doi: 10.1007/s12098-010-0219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, Boelen PA, van der Schoot M, Telch MJ. Prospective linkages between peer victimization and externalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis. Aggressive Behavior. 2011;37(3):215–222. doi: 10.1002/ab.20374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seals D, Young J. Bullying and victimization: prevalence and relationship to gender, grade level, ethnicity, self-esteem, and depression. Adolescence. 2003;38(152):735–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga Byron L, Jarvis Lorna H. Ethnic identity and acculturation in Hispanic early adolescents: Mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behaviors, and externalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13 (4):364–373. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Rodriguez L, Wang SC. The structure of cultural identity in an ethnically diverse sample of emerging adults. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 2007;29:157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist. 2010;65:237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski P, Bacallo M. Acculturation and Aggression in Latino Adolescents; A Structured Model Focusing on Cultural Risk Factors and Assets. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 34(5):757–671. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel M. Assymptotic Confidence Intervals for Indirect Effects in Strutural Equation Models. Sociological Methods. 1982;13:290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Soto C, Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto DW, Black SD, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Culutural Values Associated With Substance Use Among Hispanic Adolescents in Southern California. Substance Use and Misuse. 2011;46:1223–1233. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.567366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendsen JD, Merikangas KR. The comorbidity of depression and substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20(2):173–189. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Prado G, Burlew AK, Williams RA, Santisteban D. Drug abuse in African American and Hispanic adolescents: Culture, development, and behavior. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:77–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szapocznik J, Perez-Vidal A, Brickman AL, Foote FH, Santisteban D, Hervis O, Kurtines WM. Engaging adolescent drug abusers and their families in treatment: A strategic structural systems approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988;56(4):552–557. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.56.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Shakib S, Gallaher P, Ritt-Olson A. Cultural/interpersonal values and smoking in an ethnically diverse sample of Southern California adolescents. Journal of cultural diversity. 2006;13 (1):55–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Wagner K, Soto D, Baezconde-Garbanati L. A Comparison of Acculturation Measures Among Hispanic/Latino Adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36(4):555–565. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9184-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA. Hispanic Families in the1980’s: A Decade of Research. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1990;54(4):1015–1024. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Khoury EL, Zimmerman RS, Gil AG, Warheit GJ. Cultural Conflicts and problem behaviors in Latino Adolescents in home and school environments. Journal of Community Psychology. 1995;23:167–179. [Google Scholar]

- Vega WA, Gil A. Drug use and ethnicity in early adolescents. New York: Plenum; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Voydanoff P. Toward a Conceptualization of Perceived Work-Family Fit and Balance: A Demands and Resources Approach. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2004;67( 4):822–836. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KD, Ritt-Olson A, Chou C-P, Pokhrel P, Duan L, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Soto DW, et al. Associations between family structure, family functioning, and substance use among Hispanic/Latino adolescents. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(1):98–108. doi: 10.1037/a0018497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Nansel TR, Iannotti RJ. Cyber and Traditional Bullying: Differential Association With Depression. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2011;48(4):415–417. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 52(1):30–42. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]