Abstract

Objective

The relatively modest benefit in vasomotor symptom relief seen in clinical trials of isoflavones may reflect once-daily dosing as well as low percentages of participants able to metabolize daidzein to equol, a potentially more biologically active isoflavone. This pilot study examined whether symptom reduction was greater with more frequent administration as well as with higher daily doses. In addition, we explored possible effect modification by equol producer status.

Methods

We randomized 130 peri- (no menses in past three months) and postmenopausal (12+ months amenorrhea) women with an average of 5+ moderate/severe hot flashes per day to treatment arms with varying total daily isoflavone doses and dosing frequency, separately for equol producers and non-producers. Participants recorded daily frequency and severity of hot flashes. Analyses compared mean daily hot flash intensity scores (sum of hot flashes weighted by severity) by total daily dose and by dosing frequency. Dose- and frequency-related differences also were compared for equol producers and non-producers.

Results

Hot flash intensity scores were lowest in women randomized to the highest total daily dose (100-200mg) and in women randomized to the highest dosing frequency (2-3 times daily), with greater benefits in nighttime than in daytime scores. Dose-related and frequency-related differences were somewhat larger in equol producers than in non-producers.

Conclusions

These results suggest that a 2-3 times per day dosing frequency may improve the benefit of isoflavones for vasomotor symptom relief, particularly in equol producers and for nighttime symptoms. Larger studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords: Vasomotor symptoms, isoflavones, equol producers

Hot flashes occur in an estimated 50-80% of menopausal women in the United States,1-4 and 20-30% of women seek medical treatment for these symptoms.3-5 Exogenous hormone therapy (HT) is highly effective for symptom relief,6-7 but results from recent randomized clinical trials indicate that HT risks may outweigh benefits for many women.8-11 Consequently, HT use has declined sharply since 2002,12-13 and women are seeking alternatives, such as supplements containing isoflavones.14-17

Several recent reviews and meta analyses of randomized clinical trials assessing the effectiveness of isoflavones for vasomotor symptom (VMS) reduction18-21 indicate a beneficial effect overall. However, results across studies are mixed, likely due in part to differences in factors such as participant eligibility criteria, e.g., minimum number of hot flashes, as well as dose and composition of isoflavone treatments. Estimates of improvement in VMS frequency ranged from approximately 20% to 60%, lower than the 80-90% seen with HT,6 and Guttuso19 found that only three of 14 trials demonstrated a clinically meaningful reduction, defined as a decrease of at least two hot flashes per day.

The comparatively modest benefit in VMS reduction from isoflavones may reflect the once-daily dosing frequency used in most trials, despite isoflavones’ relatively short half-life of six-to-12 hours.18,22-23 A recent NIH workshop recommended considering frequency of administration when designing soy intervention trials.24 Several trials have used dosing frequencies higher than once per day,25-30 but to our knowledge, only two trials to date25,30 have examined multiple dosing frequencies simultaneously. In addition, equol, a metabolite of the isoflavone daidzein, may be more biologically active than daidzein,31-34 due to greater affinity for estrogen receptors.35-36 Equol also is cleared more slowly from plasma than daidzein and thus may have longer-lasting effects.35 This suggests that isoflavones’ efficacy for VMS reduction may be higher in those able to produce equol.18 Moreover, in contrast to Asian populations, only about 20-30% of Westerners produce equol,35,37 which could explain the modest effects seen in most trials in Western women. To date, effect modification by equol-producer status is not well-studied and represents an important area for research.18,31,38-39

To provide preliminary data on these questions, we conducted a pilot randomized clinical trial to explore: 1) whether the hot flash intensity score (hot flash frequency × severity) differs depending on isoflavone dosing frequency as well as on total daily dose; and 2) whether the impact of total daily dose or dosing frequency on the hot flash intensity score is greater in equol producers than in non-producers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and eligibility criteria

Participants were late perimenopausal (three to 11 consecutive months of amenorrhea) and postmenopausal women (twelve consecutive months of amenorrhea with no other cause)40 or women with a hysterectomy but at least one ovary, aged 40-69, who reported experiencing an average of five or more moderate or severe hot flashes per day in the past week. This frequency/severity criterion was consistent with other studies,26,41-43 and balanced considerations of participant representativeness44 with the ability to detect a treatment effect,18 e.g., avoiding a floor effect due to low baseline frequency. Additional criteria included willingness to record intensity and time of each hot flash in daily diaries, and to maintain current exercise and dietary patterns during the study. Exclusion criteria included bilateral oophorectomy or other iatriogenically-induced menopause as in prior studies,18,26-27,45-46 medical conditions or medications that may affect VMS or isoflavone metabolism, e.g., use of antibiotics in the past three months, and having a soy allergy or requiring a specialized diet. Women who were non-adherent during the study run-in phase – defined as completing fewer than 80% of daily diary entries or using fewer than 80% of study pills – or had fewer than an average of 5+ moderate or severe hot flashes per day, or changed their medications during the run-in phase, also were ineligible. No women declined to be randomized due to side effects during the run-in phase that were possibly isoflavone-related, such as nausea or rashes.

The goal was to recruit equal numbers of equol producers and non-producers, despite the anticipated higher percentage of non-producers in the population, in order to compare isoflavone effectiveness in producers and non-producers. After the equol non-producer sample size target was met, women determined to be non-producers during the run-in phase were not asked to participate further. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS).

Recruitment and Randomization

Participants were recruited using multiple sources and strategies, including advertising in newspapers, radio, and television, UMMS intranet messages and posters, worksite presentations, a public symposium at UMMS, health fairs and other community events, UMMS provider referrals, Registry of Motor Vehicle Electronic Billboard, and direct mailings. Participants were enrolled between June 2006 and July 2009. After establishing initial eligibility in a telephone interview, women completed an in-person visit at UMMS which included informed consent, confirmation of baseline eligibility, and collection of baseline data. Participants then entered a two-week run-in phase, during which they took placebo capsules in days 1-7 and 100mg isoflavone capsules in days 8-14. This permitted the assessment of adherence to study capsules, isoflavone-related side effects, and equol producer status. Women also completed the daily hot flash diary to confirm eligibility and provide baseline data on hot flash frequency and intensity. Remaining eligible women then underwent a seven-day washout period to eliminate any effects of the isoflavones used during the run-in phase.

Randomization to study arm was stratified by equol producer status. Separately for producers and non-producers, Stata’s ralloc command47 was used to generate a sequence of group assignments randomly permuted in blocks of size nine. The sequences for producers and non-producers were uploaded into two Access databases which were given to the study pharmacist who dispensed study capsules to participants.

Study Treatments

The original study design involved nine treatment cells per equol producer stratum: three total daily doses (placebo, 100mg/day, and 200mg/day), crossed with three dosing frequencies (once, twice, and three times per day). Due to unanticipated recruitment-related challenges, particularly identifying equol producers, midway through recruitment the number of treatment cells per equol producer stratum was reduced to four: placebo (twice per day), 200mg once per day, 100mg twice per day (200mg total daily dose), and 66mg three times per day (200mg total daily dose).

In addition, 42 women in the original protocol inadvertently received one-third of the target dose because of unclear prescription information, which led to inaccurate bottle labeling such that these participants took one tablet instead of the three tablets comprising a dose. As a result, the total daily doses in the study included placebo, 33mg, 66mg, 100mg, and 200mg. Also, equol producer status was not able to be determined in three participants due to inadequate isoflavone consumption during the second run-in week; these women were omitted from analyses of effect modification by equol producer status. The treatment duration was 12 weeks for all cells.

All study capsules, including placebo, were identical in appearance to ensure blinding. Isoflavone capsules contained Novasoy 400, a soy-based isoflavone concentrate extracted to maintain the ratio of isoflavones, and aglycone and glycoside isoforms found in soybeans and unfermented soyfoods, produced under current food Good Manufacturing Practices.48-50 Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) Company manufactured and donated the capsules, and certified that the isoflavone tablets passed tests for quality assurance and control, including total isoflavone content, microbiology, and stability properties. A subsample of capsules, 100 placebo, 300 33mg, and 300 50mg, were sent to an independent lab, Plant Biactives Analytical, for confirmation of total isoflavone amounts (see Table 1 for capsule compositions, including calculated levels of aglycone equivalents) and to check for impurities, including heavy metals, disintegration, and bioactive components. The placebo was assayed for isoflavones and four heavy metals (arsenic, mercury, lead, cadmium). The soy product (33mg and 50mg) was assayed for variability of total isoflavone content with a sample of 36 samples (6 tablets per concentration), as well as the estrogenic compounds estradiol, estrone, estriol, ethynylestradiol, and tamoxifen. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine accepted ADM’s certification of pesticides, heavy metals, and product stability in March 2006.

TABLE 1. Composition of study capsules.

| Aglycone, mg/dose |

Glycoside, mg/tablet |

Glycoside isoflavone, mg/dose |

Aglycone equol isoflavone, mg/tablet |

Aglycone equol isoflavone, mg/dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | 00.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 33 mg | 11.65 | 34.96 | 7.51 | 22.54 |

| 50 mg | 16.59 | 49.76 | 10.69 | 32.06 |

| 66 mg | 21.58 | 64.74 | 13.91 | 41.72 |

| 100 mg | 28.89 | 86.68 | 18.63 | 55.89 |

| 200 mg | 60.39 | 181.17 | 38.95 | 116.86 |

Data are presented as mean.

Determination of equol producer status

At the completion of isoflavone consumption in the second week of the run-in phase, participants provided a first-morning urine sample, which was analyzed to determine equol producer status as follows. Urine samples (4 mL) were analyzed for equol and daidzein by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry as described previously.51 A deuterated internal standard was used for each target compound. The interassay CVs were <15.0 % for equol and daidzein. Limit of quantitation for all isoflavone targets was 5.0 ng/mL in urine. Women with urinary equol concentrations ≥90ng/mL were defined as equol producers.52 Participants who were determined by pill counts not to be compliant were asked to repeat the process.

Measures

After the run-in phase, participants completed daily hot flash diaries for 12 weeks, and repeated in-person assessments at weeks 9 and 15. The outcome measure was hot flash intensity score,53 computed as the weighted sum of hot flashes, weighting each hot flash by its intensity (1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe/very severe). Daytime and nighttime hot flashes (night sweats) were considered separately. Women recorded hot flashes and associated bother (1=not at all to 4=extremely bothered) on a daily basis during the 12 weeks of treatment and returned the diaries by mail each week. Weekly average scores were computed to smooth out day-to-day variability as in a previous study.54

Information on sociodemographic characteristics, menopause status, medication use, health behaviors (smoking, body mass index), dietary soy consumption, perceived stress,55 and menopause-related quality of life was collected at the baseline visit. Scales for the latter included Menopause-Related Quality of Life (MENQOL),56 the Greene climacteric scale,57 and the Hot Flash Related Daily Interference Scale.58 Soy consumption also was measured at the 9-week and 15-week visits. Adherence to study medication was assessed by capsule count at weeks 9 and 15. In addition, participants received at least two safety assessment calls, which also assisted in participant retention. All data collectors and data entry staff were blinded to treatment assignment.

Statistical Methods

Equol producers and non-producers were compared regarding baseline characteristics, using frequencies and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, and means and standard deviations and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous variables.

To assess the effects of isoflavone total daily dose and dosing frequency on hot flashes, weekly hot flash intensity score was modeled using linear mixed modeling59 as a function of week (follow-up weeks 1 through 12, treated as categorical to allow for nonlinear trajectories) and treatment arm, with adjustment for baseline hot flash intensity score to account for possible regression to the mean.60 To examine whether dose- and frequency-related differences varied by equol producer status, we added equol producer status and its interaction with treatment arm to the models. Scores were transformed as log((follow-up score+1) / (baseline score +1)) as in the study by Avis and colleagues61 to obtain normally distributed outcomes, and results were back-transformed to percent change since baseline. for graphical presentation. Daytime and nighttime scores were modeled separately. Parallel models were estimated for absolute change in daytime plus nighttime hot flash frequency, to explore whether clinically meaningful reductions (2+ per day) occurred.

To avoid small cell counts, we collapsed total daily doses 33mg/day and 66mg/day, and total daily doses 100mg/day and 200mg/day, as well as two and three times per day, as indicated by preliminary analyses. In addition, all placebo cells were combined into a single group. We also considered the two dimensions of treatment, total daily dose and dosing frequency, separately rather than jointly in order to increase cell counts. Adjustment for dosing frequency had little effect on dose-related associations with hot flash scores, and vice versa; in addition, including an interaction between dose and frequency did not improve model fit appreciably (data not shown). Consequently, results for dose and frequency are presented separately.

In sensitivity analyses, models were re-run on the subset of adherent participants, defined as those taking 80+% of study pills according to self-report; results were similar (data not shown), likely due to the high rate of adherence (83.6%). Additional sensitivity analyses imputed the last observation carried forward for missing weekly hot flash data; results were similar (data not shown). We also adjusted for several baseline characteristics predictive (p<0.05) of change in daytime or nighttime hot flash intensity score: perceived stress, the MENQOL summary score, bother from hot flashes, and menopause status. Adjusted results were generally similar (data not shown) and were based on a smaller sample size because of missing covariate data; thus, we present primarily unadjusted results. All analyses were intention to treat. Because this was a pilot study, p-values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

RESULTS

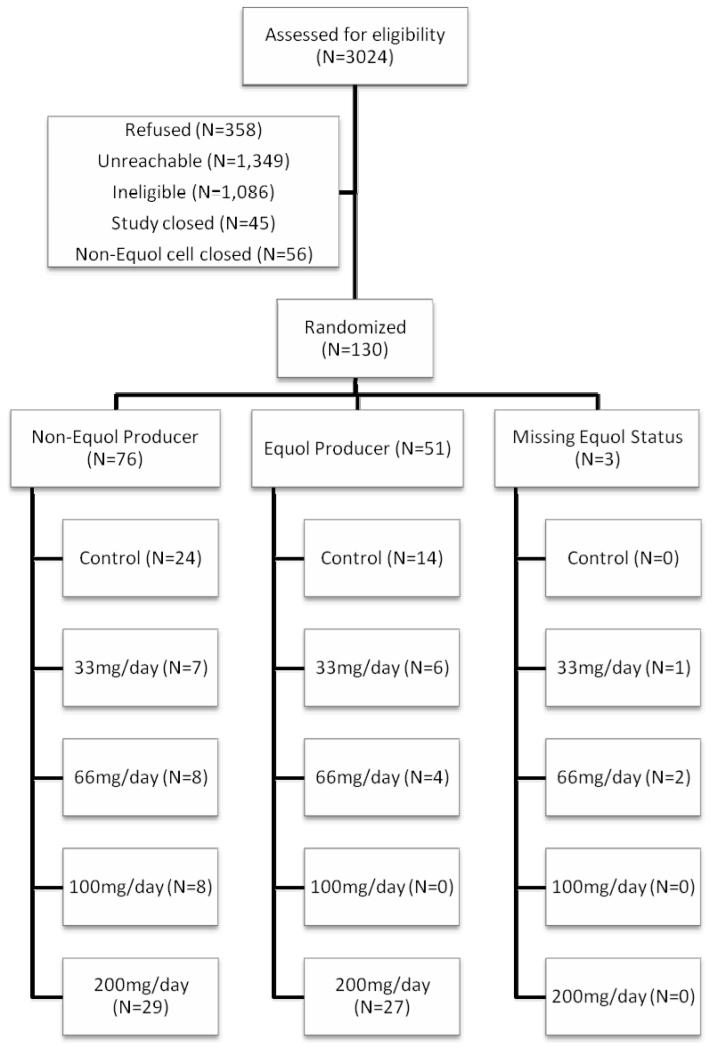

As seen in the CONSORT diagram (Figure 1), 130 eligible women agreed to participate and were randomized, 76 of whom were equol non-producers, 51 of whom were equol producers, and three of whom had unknown equol producer status. Among non-producers, 24 were randomized to placebo; 15 were randomized to a low dose (33-66mg), and 37 to a high dose (100-200mg); and 16 were randomized to once-daily dosing and 36 to more frequent dosing. Among equol producers, 14 were randomized to placebo; 10 were randomized to a low dose and 27 to a high dose; and 12 were randomized to once-daily dosing and 25 to more frequent dosing. Two women did not provide follow-up data and thus were excluded from all primary analyses; both were equol non-producers, both were randomized to 200mg total daily dose, and one was randomized to once per day and the other to twice per day.

FIG. 1.

Consort diagram: flow of participants through the study.

Baseline characteristics by equol producer status are presented in Table 2. Among producers, none were assigned to 100mg/day and a higher percentage were assigned to 200mg/day than among non-producers, because a larger proportion of producers were enrolled after the simplification of the study design. Other statistically significant differences included a lower percentage of producers reporting vasomotor symptom benefit from antidepressant medication, a higher percentage who were late perimenopausal and a corresponding lower mean age, and a lower Greene vasomotor subscale score. None of these characteristics was significantly associated with baseline-adjusted daytime or nighttime hot flash intensity. No other differences between equol producers and non-producers were statistically significant. On average, women reported 7.2 daytime and 2.9 nighttime hot flashes per day, with an average bother level of 3.1 (moderately bothered). Mean soy consumption was low, at under 1.5 servings per week; consumption remained stable over the study period, with a mean within-woman change in number of foods consumed at least twice per month of −0.05 (standard deviation 2.7). Equol producers and non-producers did not differ regarding urinary concentration of daidzein, but as expected, producers had significantly higher concentrations of equol; all equol non-producers in this study had urinary equol concentrations below the level of quantitation (5 ng/ml).

TABLE 2. Baseline characteristics of participants by equol producer status.

| All participants (N = 130)a |

Equol nonproducers (n = 76) |

Equol producers (n = 51) |

P b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily dosing frequency, n (%) |

||||

| Placebo | 38 (29.2) | 24 (31.6) | 14 (27.5) | 0.9672 |

| Once | 30 (23.1) | 16 (21.1) | 12 (23.5) | |

| Twice | 31 (23.9) | 18 (23.7) | 13 (25.5) | |

| Thrice | 31 (23.9) | 18 (23.7) | 12 (23.5) | |

| Total daily dose, n (%) |

||||

| Placebo | 38 (29.2) | 24 (31.6) | 14 (27.5) | 0.0910 |

| 33 mg/d | 14 (10.8) | 7 (9.2) | 6 (11.8) | |

| 66 mg/d | 14 (10.8) | 8 (10.5) | 4 (7.8) | |

| 100 mg/d | 8 (6.2) | 8 (10.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 200 mg/d | 56 (43.1) | 29 (38.2) | 27 (52.9) | |

| Age, mean (SD), y |

54.5 (4.7) | 55.1 (4.9) | 53.4 (4.2) | 0.0397 |

| Menopause status, n (%) |

||||

| Late perimenopausal |

31 (23.9) | 11 (14.5) | 20 (39.2) | 0.0062 |

|

Postmenopausal |

78 (60.0) | 52 (68.4) | 23 (45.1) | |

| Hysterectomy | 21 (16.2) | 13 (17.1) | 8 (15.7) | |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 |

27.9 (4.9) | 27.6 (4.9) | 28.4 (5.0) | 0.2082 |

| Current smoker, n (%) |

4 (3.9) | 1 (1.8) | 3 (6.7) | 0.3211 |

| Total kilocalories, mean (SD) |

1,947 (732) | 2,002 (739) | 1,874 (730) | 0.5095 |

| Any alcohol consumption, n (%) |

91 (70.0) | 54 (71.1) | 35 (68.6) | 0.8441 |

| Alcohol servings per day (drinkers only), mean (SD) |

0.8 (0.8) | 0.9 (0.8) | 0.8 (0.7) | 0.9100 |

| Any physical activity in the past 28 d, n (%) |

98 (83.1) | 60 (82.2) | 35 (83.3) | 1.0000 |

| MET hours (those with any physical activity only), mean (SD) |

2.7 (2.5) | 2.7 (2.7) | 2.7 (2.3) | 0.6438 |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) |

||||

| Non-Hispanic white |

111 (91.7) | 64 (90.1) | 44 (93.6) | 0.9251 |

| African American |

5 (4.1) | 3 (4.2) | 2 (4.3) | |

| Hispanic | 3 (2.5) | 2 (2.8) | 1 (2.1) | |

| Native American |

2 (1.7) | 2 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Perceived stress, mean (SD) |

21.3 (8.0) | 21.1 (7.8) | 21.5 (8.5) | 0.9433 |

| Soy servings per week, mean (SD) |

1.4 (2.6) | 1.0 (2.2) | 1.9 (3.0) | 0.1842 |

| Prescription hormone therapy use in the past year, n (%) |

14 (10.9) | 9 (11.8) | 5 (10.0) | 1.0000 |

| Natural (nonprescription) hormone use in the past year, n (%) |

29 (22.3) | 17 (21.5) | 12 (23.5) | 0.5287 |

| No | 95 (74.8) | 56 (74.7) | 37 (75.5) | |

| Yes, helped | 14 (11.0) | 7 (9.3) | 7 (14.3) | |

| Yes, did not help |

18 (14.2) | 12 (16.0) | 5 (10.2) | |

| Antidepressant medication for hot flashes, n (%) |

||||

| No | 111 (86.7) | 67 (88.2) | 42 (85.7) | 0.0410 |

| Yes, helped | 8 (6.3) | 2 (2.6) | 6 (12.2) | |

| Yes, did not help |

9 (7.0) | 7 (9.2) | 1 (2.0) | |

| Prescription medication for osteoporosis, n (%) |

14 (10.8) | 8 (10.5) | 5 (9.8) | 1.0000 |

| Prescription medication for high cholesterol, hypertension, and diabetes, n (%) |

50 (38.5) | 33 (43.4) | 17 (33.3) | 0.2724 |

| Greene Climacteric Scale |

||||

| Vasomotor score, mean (SD) |

4.3 (1.4) | 4.4 (1.4) | 4.0 (1.3) | 0.0715 |

| Total score, mean (SD) |

21.4 (11.8) | 22.2 (12.3) | 19.8 (11.2) | 0.3562 |

| Menopause- Related Quality of Life |

||||

| Vasomotor score, mean (SD) |

6.5 (1.2) | 6.5 (1.1) | 6.3 (1.3) | 0.3545 |

| Total score, mean (SD) |

5.3 (1.0) | 5.3 (0.9) | 5.2 (1.1) | 0.8489 |

| Hot Flash Related Daily Interference Scale, mean (SD) |

44.0 (20.2) | 44.9 (21.7) | 41.0 (16.8) | 0.5929 |

| Number of hot flashes per day, mean (SD) |

7.2 (3.7) | 6.1 (3.7) | 7.2 (3.3) | 0.3789 |

| Daytime hot flash intensity score, mean (SD) |

17.0 (10.3) | 16.5 (10.5) | 16.6 (8.9) | 0.5945 |

| Number of hot flashes per night, mean (SD) |

2.9 (1.9) | 2.7 (1.7) | 2.9 (1.8) | 0.3182 |

| Nighttime hot flash intensity score, mean (SD) |

7.5 (5.0) | 7.2 (4.9) | 7.5 (4.4) | 0.3896 |

| Bother from hot flashes, mean (SD) |

3.1 (0.5) | 3.1 (0.5) | 3.0 (0.4) | 0.1988 |

| Urinary daidzein, mean (SD), ng/mL |

1,630 (1,250) | 1,720 (1,238) | 1,590 (1,245) | 0.4006 |

| Urinary equol, mean (SD), ng/mL |

– c | – c | 2,220 (1,409) | <0.0001 |

MET, metabolic equivalent of task.

Equol producer status unknown for three participants.

Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables.

Equol concentrations for nonproducers were below the level of quantitation.

Among the 128 women with any follow-up data, retention – defined as returning 80+% of follow-up diaries – was 90.6% overall, ranging from 83.9% in the high-dose group to 97.4% in the placebo group (exact p-value = 0.054), and from 85.3% in the high-frequency group to 97.4% in the placebo group (exact p-value = 0.14). Adherence to study capsules – defined as taking 80+% of capsules according to self-report – ranged from 75.8% in the high-dose group to 92.9% in the low-dose group (exact p-value=0.09), and from 80.3% in the high-frequency group to 89.5% in the placebo group (exact p-value=0.50). On average, 49.6 days (standard deviation 17.2) elapsed between baseline and the start of follow-up, with no statistically significant differences by total daily dose (p=0.59) or by dosing frequency (p=0.92). During the run-in phase, 16 women (12.3%) reported at least one side effect possibly related to isoflavone consumption, including nausea, diarrhea, heartburn, breast tenderness, or rash. The percentage of participants reporting any of these side effects during study follow-up was 34.4% overall, 34.2% for women randomized to placebo, 46.4% for women randomized to 33-66mg/day, and 29.0% for women randomized to 100-200mg/day (exact p-value=0.24), and 41.4% in women randomized to once daily and 31.1% in women randomized to 2-3 times daily (exact p-value=0.62). Also, 18.8% of participants reported an antibiotic prescription during follow-up, with no significant differences by total daily dose or dosing frequency.

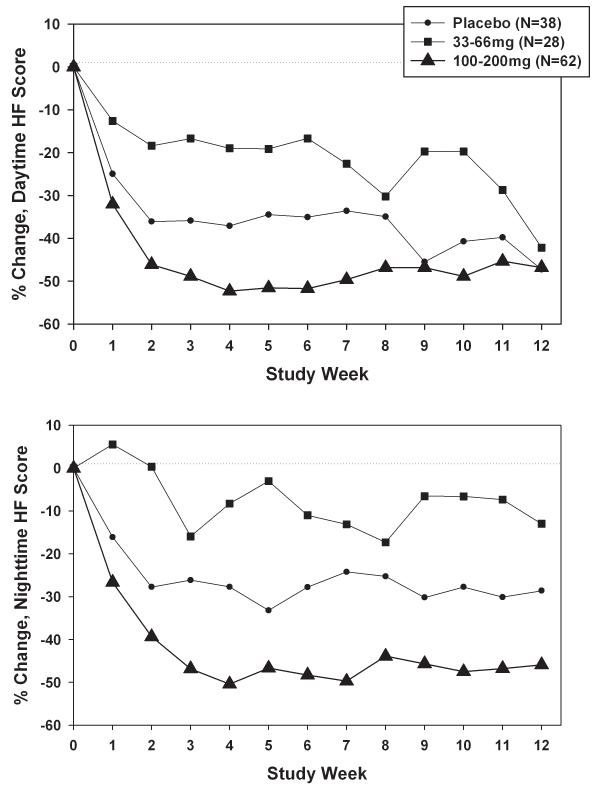

Change in hot flash intensity scores by total daily dose

Figure 2a presents percent change in daytime hot flash intensity scores by total daily dose, accounting for within-woman correlation. Declines tended to be largest for the 100-200mg group, but smallest in the 33-66mg group rather than in the placebo group. Dose-related differences were not statistically significant overall (p=0.19). Corresponding results for nighttime hot flash intensity scores (Figure 2b) showed a similar pattern, with wider and statistically significant (overall p=0.02) differences between the dose groups, particularly the 33-66mg and 100-200mg groups (pairwise difference p=0.006). Mean absolute change in daytime plus nighttime hot flash frequency was −2.4 for placebo, −0.9 for 33-66mg, and −3.3 for 100-200mg, with a mean difference of 2.4 for high versus low dose.

FIG. 2.

A: Percent change in daytime hot flash (HF) intensity, adjusted for baseline daytime HF intensity, by total daily dose weekly during the intervention. B: Percent change in nighttime HF intensity, adjusted for baseline nighttime HF intensity, by total daily dose weekly during the intervention.

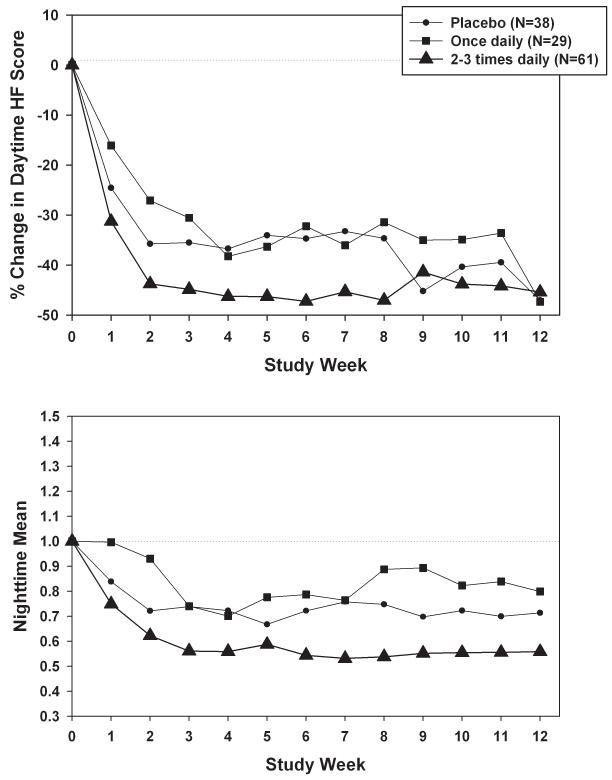

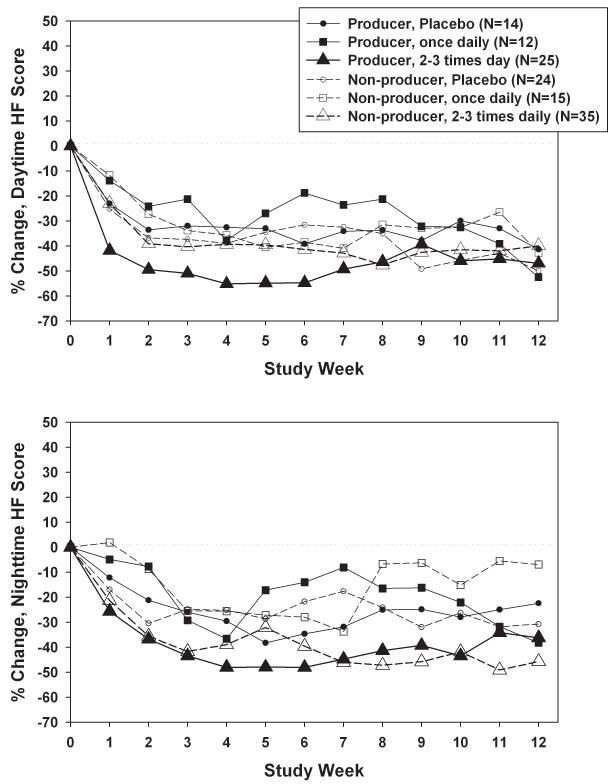

Change in hot flash intensity scores by dosing frequency

Analogous results for dosing frequency versus daytime hot flash intensity scores are presented in Figure 3a. Declines tended to be largest for the 2-3 times daily group, and smallest for the once daily group. Dosing frequency-related differences were not statistically significant (p=0.74), however, and were smaller in magnitude than corresponding differences for total daily dose. Patterns in nighttime hot flash intensity scores (Figure 3b) were consistent, with larger frequency-related differences (p=0.06) than for daytime scores, particularly for the 2-3 times daily group versus the once daily group (p=0.02). Mean absolute change in daytime plus nighttime hot flash frequency was −2.3 for placebo, −2.5 for once daily, and −2.6 for 2-3 times daily.

FIG. 3.

A: Percent change in daytime hot flash (HF) intensity, adjusted for baseline daytime HF intensity, by dosing frequency weekly during the intervention. B: Percent change in nighttime HF intensity, by dosing frequency weekly during the intervention.

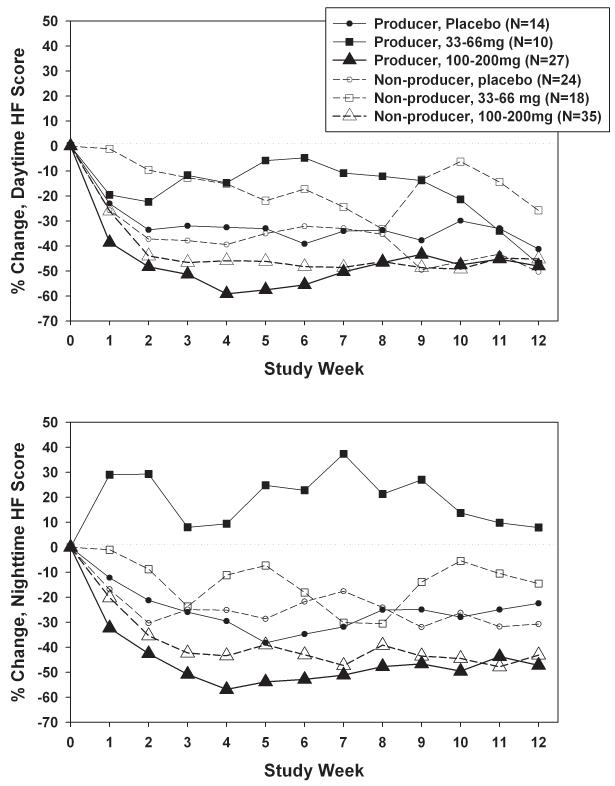

Effect modification by equol producer status

Separation between dose groups in daytime hot flash intensity scores was somewhat larger for equol producers than non-producers (Figure 4a), but effect modification by equol producer status was not statistically significant (p=0.26 for dose × equol producer status). Adjustment for covariates reduced the equol producer-related difference in the highest dose, from −48.1% for producers versus −39.3% for non-producers (p=0.21) to −41.5% for producers versus −42.8% for non-producers (p=0.87; adjusted p=0.99 for dose × equol producer status). The pattern was similar for nighttime hot flash intensity scores (Figure 4b), with greater between-dose differences among equol producers (p=0.02) than non-producers (p=0.40), due in part to the lack of decline among equol producers randomized to 33-66mg. Effect modification by equol producer status was not statistically significant, however (p=0.45). The impact of adjustment for covariates on dose-related differences within equol producer stratum was relatively small (adjusted p=0.28 for equol× dose). For both daytime and nighttime hot flash intensity, equol producers had consistently larger declines than non-producers only in the subset of women randomized to 100-200mg, although these differences by equol producer status were not statistically significant (p=0.21 and 0.53 respectively).

FIG. 4.

A: Percent change in daytime hot flash (HF) intensity, adjusted for baseline daytime HF intensity, by total daily dose and equol producer status weekly during the intervention. B: Percent change in nighttime HF intensity, adjusted for baseline nighttime HF intensity, by total daily dose and equol producer status weekly during the intervention. C: Mean percent change in daytime HF intensity, adjusted for baseline daytime HF intensity, by dosing frequency and equol producer status weekly during the intervention. D: Percent change in nighttime HF intensity, adjusted for baseline nighttime HF intensity, by dosing frequency and equol producer status weekly during the intervention.

Between-group differences in daytime hot flash intensity scores for dosing frequency (Figure 4c) were somewhat larger for equol producers than non-producers, but effect modification was not statistically significant (p=0.23). Adjustment for covariates reduced the equol producer-related difference in the highest frequency, from −49.5% for producers versus −34.1% for non-producers (p=0.04) to −38.0% for producers versus −37.6% for non-producers (p=0.90; adjusted p=0.97 for dose × equol producer status). Results for nighttime hot flash intensity scores (Figure 4d) were similar (p=0.53 for frequency × equol producer status), with little impact from adjustment for covariates.

DISCUSSION

Analyses from this pilot study suggest a greater percent reduction in both daytime and nighttime hot flash intensity scores with a high isoflavone dose, as seen in previous studies.18 A total daily dose of 33-66mg, however, did not confer benefits compared with placebo, consistent with results from Ishiwata and colleagues,30 where the low-dose/low-frequency group had the lowest symptom declines. The average decline in total hot flash frequency was 2.4 per day greater for the 100-200mg dose than for the 33-66mg dose, a clinically meaningful difference.19 For dosing frequency, percent declines in hot flash intensity tended to be largest for the 2-3 times daily group, but smallest for the once daily group, again consistent with Ishiwata and colleagues.30 Moreover, frequency-related differences were smaller than dose-related differences for both daytime and nighttime scores. Differences between frequency groups in terms of absolute decline in total hot flash frequency, however, did not exceed the clinically significant cutoff of 2+/day.19 For both dose and frequency, between-group differences were larger for nighttime scores than for daytime scores. The advantage of being an equol producer rather than non-producer was confined primarily to the high-dose and high-frequency groups, and this effect modification by equol producer status was not large enough to be statistically significant, due in part to small sample sizes.

Almost all prior trials of isoflavones and hot flashes have focused on the role of dose,18 and most of these have used once-daily dosing. Among trials examining dosing frequencies higher than once per day, only two trials have compared multiple frequencies directly. Ishiwata and colleagues30 found improvements in the vasomotor score in women randomized to S-equol three times daily compared with placebo, but no differences versus placebo for women randomized to once daily; total daily dose, however, was confounded with frequency such that women randomized to greater dosing frequency also received a higher dose. Washburn and colleagues25 found greater improvements in hot flash severity for twice daily, but not for once daily, versus placebo. Our results, although not always statistically significant, are consistent. The advantage of more frequent dosing may result from better maintenance of isoflavone or equol levels over time. Pharmacokinetic analyses of equol indicate that twice-daily dosing is sufficient to maintain steady plasma levels.62

Regarding the role of equol, an observational study in Japan noted milder hot flashes among equol producers than non-producers,63 and several trials found that equol administration reduced hot flashes,28-30 including among equol non-producers.28 Ishiwata and colleagues30 also assessed effect modification by equol producer status, and found that receiving equol three times daily reduced vasomotor symptoms compared with placebo, but only in the non-producers. In contrast, two other trials using a supplement with a combination of daidzein, genistein, and glycitein found effect modification in the opposite direction, i.e., larger reductions in hot flashes among equol producers.64-65 The current study, which also administered a combination of daidzein, genistein, and glycitein, found results similar to the latter trials. Differences across studies may reflect both the type of supplementation, i.e., daidzein versus equol, as well as participants’ typical consumption of isoflavones. All three studies of effect modification by equol producer status cited above were conducted in Japanese or Taiwanese women, where isoflavone consumption tends to be relatively high compared with Western populations.66 Another study also suggests that early-life exposure to isoflavones is necessary for later-life equol production capability.67 In combination, however, these results suggest the importance of equol in reducing vasomotor symptoms, either as a result of direct supplementation or through conversion of daidzein to equol.

Limitations of this study include its pilot nature and consequently small sample sizes. Cell sizes were too small for a well-powered examination of the interaction of total daily dose and dosing frequency, e.g., to test whether 100-200mg/day is significantly more effective when spread out over multiple administrations than when taken all at once. In addition, we did not have sufficient numbers of women randomized to placebo to compare different dosing frequencies, and thus cannot examine whether dosing frequency per se, in the absence of isoflavone administration, affects hot flash intensity scores. We also did not measure serum or urinary equol during follow-up. As a result, despite verification of adherence and thus daidzein exposure via capsule counts, safety monitoring calls, and self-reported capsule consumption in diaries, each participant’s actual exposure to equol is unknown due to between-person variability in the efficiency of conversion of daidzein to equol.68-69 Given the likely range in equol levels, the magnitude of exposure in some participants may have been insufficient for hot flash reduction even among equol producers.

The study had a number of strengths, however. We included perimenopausal as well as postmenopausal women, because hot flashes peak in the years near the final menstrual period.70 Hot flash data were collected prospectively using daily diaries, as required by the Food and Drug Administration,19 and daytime and nighttime hot flashes were measured and analyzed separately. The duration of intervention and follow-up was 12 weeks, consistent with prior studies and recommendations.18,71 Innovative features include an examination of both dosing frequency and effect modification by equol producer status. To date, only a few prior trials have compared multiple dosing frequencies. In addition, this was one of the few studies to stratify sampling and randomization by equol producer status, and also one of the few that included non-Asian women, who tend to have low typical and early-life isoflavone consumption.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this pilot study in women with typically low isoflavone consumption provided preliminary evidence that isoflavone administration at least twice per day may provide greater hot flash relief than once daily. Also, any benefit from more frequent dosing – as well as from higher total doses – may occur primarily in equol producers. Larger studies, including an examination of the impact of dosing frequency in the placebo group, are needed to confirm and extend these findings.

Acknowledgments

Funding/support: This study was supported by National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Grant AT002522. The authors also acknowledge Archer Daniels Midland Company (ADM) for their contribution of Novasoy 400 and placebo capsules.

Footnotes

Financial disclosure/conflicts of interest: None

Disclaimers: None

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gold EB, Sternfeld B, Kelsey JL, Brown C, Mouton C, Reame N, Salamone L, Stellato R. Relation of demographic and lifestyle factors to symptoms in a multi-racial/ethnic population of women 40-55 years of age. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:463–73. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kronenberg F. Hot flashes: epidemiology and physiology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1990;592:52–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1990.tb30316.x. discussion 123-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Avis NE, Crawford SL, McKinlay SM. Psychosocial, behavioral, and health factors related to menopause symptomatology. Womens Health. 1997;3:103–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grady D. Management of menopausal symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2338–2347. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp054015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guthrie JR, Dennerstein L, Taffe JR, Donnelly V. Health care-seeking for menopausal problems. Climacteric. 2003 Jun;6(2):112–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crandall C. Low-dose estrogen therapy for menopausal women: a review of efficacy and safety. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12:723–747. doi: 10.1089/154099903322447701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.North American Menopause Society The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–271. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31824b970a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossouw JE, Anderson GL, Prentice RL, et al. Risks and benefits of estrogen plus progestin in healthy postmenopausal women: principal results From the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002 Jul 17;288(3):321–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson GL, Limacher M, Assaf AR, Bassford T, Beresford SA, Black H, et al. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;291:1701–12. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.14.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grady D, Herrington D, Bittner V, et al. Cardiovascular disease outcomes during 6.8 years of hormone therapy: Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study follow-up (HERS II) JAMA. 2002;288(1):49–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hulley S, Furberg C, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Noncardiovascular disease outcomes during 6.8 years of hormone therapy: Heart and Estrogen/progestin Replacement Study follow-up (HERS II) JAMA. 2002;288(1):58–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai SA, Stefanick ML, Stafford RS. Trends in menopausal hormone therapy use of US office-based physicians, 2000-2009. Menopause. 2011;18:385–392. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181f43404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ettinger B, Wang SM, Leslie RS, Patel BV, Boulware MJ, Mann ME, McBride M. Evolution of postmenopausal hormone therapy between 2002 and 2009. Menopause. 2012;19:610–615. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31823a3e5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newton KM, Buist DS, Keenan NL, Anderson LA, LaCroix AZ. Use of alternative therapies for menopause symptoms: results ofa population-based survey. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:18–25. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bair YA, Gold EB, Zhang G, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine during the menopause transition: longitudinal results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Menopause. 2008;15:32–43. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31813429d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gold EB, Bair Y, Zhang G, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of specific complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by racial/ethnic group and menopausal status: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Menopause. 2007;14:612–623. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31802d975f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keenan N, Mark S, Fugh-Berman A, Browne D, et al. Severity of menopausal symptoms and use of both conventional and complementary/alternative therapies. Menopause. 2003;10(6):507–515. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000064865.58809.3E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.North American Menopause Society The role of soy isoflavones in menopausal health: report of The North American Menopause Society/Wulf H. Utian Translational Science Symposium in Chicago, IL (October 2010) Menopause. 2011;18(7):732–53. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31821fc8e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guttuso T., Jr. Effective and clinically meaningful non-hormonal hot flash therapies. Maturitas. 2012;72(1):6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolaños R, Del Castillo A, Francia J. Soy isoflavones versus placebo in the treatment of climacteric vasomotor symptoms: systematic review and meta-analysis. Menopause. 2010;17(3):660–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taku K, Melby MK, Kronenberg F, Kurzer MS. Extracted or synthesized soybean isoflavones reduce menopausal hot flash frequency and severity: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Menopause. 2012;19:776–790. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182410159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Setchell KD, Brown NM, Desai P, et al. Bioavailability of pure isoflavones in healthy humans and analysis of commercial soy isoflavone supplements. J Nutr. 2001;131(4 Suppl):1362S–1375S. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.4.1362S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Setchell KD, Faughnan MS, Avades T, et al. Comparing the pharmacokinetics of daidzein and genistein with the use of 13C-labeled tracers in premenopausal women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003 Feb;77(2):411–419. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.2.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klein MA, Nahin RL, Messina MJ, et al. Guidance from an NIH workshop on designing, implementing and reporting clinical studies of soy interventions. J Nutr. 2010;140:1192S–1204S. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.121830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Washburn S, Burke GL, Morgan T, Anthony M. Effect of soy supplementation on serum lipoproteins, blood pressure, and menopausal symptoms in perimenopausal women. Menopause. 1999;6(1):7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Faure ED, Chantre P, Mares P. Effects of a standardized soy extract on hot flushes: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Menopause. 2002;9:329–334. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200209000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han KK, Soares JM, Haidar MA, Rodrigues de Lima G, Baracat EC. Benefits of soy isoflavone therapeutic regimen on menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:389–94. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01744-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aso T, Uchiyama S, Matsumura Y, Taguchi M, Nozaki M, Takamatsu K, Ishizuka B, Kubota T, Mizunuma H, Ohta H. A natural S-equol supplement alleviates hot flushes and other menopausal symptoms in equol nonproducing postmenopausal Japanese women. J Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(1):92–100. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.2753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenks BH, Iwashita S, Nakagawa Y, Ragland K, Lee J, Carson WH, Ueno T, Uchiyama S. A pilot study on the effects of S-equol compared to soy isoflavones on menopausal hot flash frequency and other menopausal symptoms. J Women’s Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(6):674–82. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2011.3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishiwata N, Melby MK, Mizuno S, Watanabe S. New equol supplement for relieving menopausal symptoms: randomized, placebo-controlled trial of Japanese women. Menopause. 2009;16(1):141–8. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31818379fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lampe JW. Is equol the key to the efficacy of soy foods? Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):1664S–1667S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.26736T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Setchell KDR, Clerici C. Equol: history, chemistry, and formation. J Nutr. 2010;140:1355S–1362S. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.119776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Setchell KDR, Clerici C. Equol: pharmacokinetics and biological actions. J Nutr. 2010;140:1363S–1368S. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.119784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Setchell KD, Cole SJ. Method of defining equol-producer status and its frequency among vegetarians. J Nutr. 2006;136:2188–2193. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.8.2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Setchell KDR, Brown NM, Lydeking-Olsen E. The clinical importance of the metabolite equol – A clue to the effectiveness of soy and its isoflavones. J Nutr. 2002;132:3577–3584. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.12.3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muthyala RS, Ju YH, Sheng S, et al. Equol, a natural estrogenic metabolite from soy isoflavones: convenient preparation and resolution of R- and S-equols and their different binding and biological activity through estrogen receptors α and β. Bioorg Med Chem. 2004;12:1559–1567. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2003.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnes S, Kim H. Cautions and research needs identified at the equol, soy, and menopause research leadership conference. J Nutr. 2010;140:1390S–1394S. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.120626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newton KM, Grady D. Soy isoflavones for prevention of menopausal bone loss and vasomotor symptoms: comment on “Soy isoflavones in the prevention of menopausal bone loss and menopausal symptoms”. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1363–9. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shor D, Sathyapalan T, Atkin SL, Thatcher NJ. Does equol production determine soy endocrine effects? Eur J Nutr. 2012;51(4):389–98. doi: 10.1007/s00394-012-0331-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrott E, et al. Executive summary: Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) Fertil Steril. 2001;76:874–878. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(01)02909-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tice JA, Ettinger B, Ensrud K, Wallace R, Blackwell T, Cummings SR. Phytoestrogen supplements for the treatment of hot flashes: the Isoflavone Clover Extract (ICE) Study: a randomized controlled trial [see comment] JAMA. 2003;290:207–214. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guttuso T, Jr, Kurlan R, McDermott MP, Kieburtz K. Gabapentin’s effects on hot flashes in postmenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:337–345. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02712-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van de Weijer PH, Barentsen R. Isoflavones from red clover (Promensil) significantly reduce menopausal hot flush symptoms compared with placebo. Maturitas. 2002;42:187–193. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(02)00080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Newton KM, Reed SD, Grothaus L, Ehrlich K, Guiltinan J, Ludman E, LaCroix AZ. The Herbal Alternatives for Menopause (HALT) Study: background and study design. Maturitas. 2005;52:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Albertazzi P, Pansini F, Bonaccorsi G, Zanotti l, Forini E, Aloysio DD. The effect of dietary soy supplementation on hot flushes. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:6–11. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(97)00597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Burke GL, Legault C, Anthony M, et al. Soy protein and isoflavone effects on vasomotor symptoms in peri- and postmenopausal women: the Soy Estrogen Alternative Study. Menopause. 2003;10:147–153. doi: 10.1097/00042192-200310020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.StataCorp . Stata Statistical Software: Release 9. StataCorp LP; College Station, TX: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Griffith AP, Collison MW. Improved methods for the extraction and analysis of isoflavones from soy-containing foods and nutritional supplements by reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2001;913:397–413. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)01077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Erdman JW, Jr, Badger TM, Lampe JW, Setchell KDR, Messina M. Not all soy products are created equal: caution needed in interpretation of research results. J Nutr. 2004;134(5):1229S–1233S. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.5.1229S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williamson-Hughes P, Flickinger BD, Messina MJ, Empie MW. Isoflavone supplements containing predominantly genistein reduce hot flash symptoms: a critical review of published studies. Menopause. 2006;13:831–9. doi: 10.1097/01.gme.0000227330.49081.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Frankenfeld CL, McTiernan A, Tworoger SS, et al. Serum steroid hormones, sex hormone-binding globulin concentrations, and urinary hydroxylated estrogen metabolites in post-menopausal women in relation to daidzein-metabolizing phenotypes. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;88:399–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Atkinson C, Newton KM, Bowles EJ, Yong M, Lampe JW. Demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors and dietary intakes in relation daidzein-metabolizing phenotypes among premenopausal women in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:679–87. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.3.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sloan JA, Loprinzi CL, Novotny PJ, Barton DL, Lavasseur BI, Windschitl H. Methodologic lessons learned from hot flash studies. J Clin Oncol. 2001 Dec 1;19(23):4280–4290. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.23.4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Carmody J, Crawford S, Salmoirago-Blotcher E, Leung K, Churchill L, Olendzki N. Mindfulness training for coping with hot flashes: Results of a randomized trial. Menopause. 2011;18(6):611–620. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e318204a05c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hilditch JR, Lewis J, Ross AH, et al. A comparison of the effects of oral conjugated equine estrogen and transdermal estradiol-17β combined with an oral progestin on quality of life in postmenopausal women. Maturitas. 1996;24:177–184. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(96)82007-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greene JG. Constructing a standard climacteric scale. Maturitas. 1998;29:25–31. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5122(98)00025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Carpenter J. The Hot Flash Related Daily Interference Scale: a tool for assessing the impact of hot flashes on quality of life following breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22(6):979–989. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fitzmaurice GM, Laird NM, Ware JH. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chuang-Stein C, Tong DM. The impact and implication of regression to the mean on the design and analysis of medical investigations. Stat Methods Med Res. 1997;6:115–128. doi: 10.1177/096228029700600203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Avis NE, Legault C, Coeytaux RR, et al. A randomized, controlled pilot study of acupuncture treatment for hot flashes. Menopause. 2008;15(6):1070–1078. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e31816d5b03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jackson RL, Greiwe JS, Desai PB, Schwen RJ. Single-dose and steady-state pharmacokinetic studies of S-equol, a potent nonhormonal, estrogen receptor β-agonist being developed for the treatment of menopausal symptoms. Menopause. 2011;18(2):185–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Uchiyama S, Ueno T, Masaki K, Shimizu S, Aso T, Shirota T. The cross-sectional study of the relationship between soy isoflavones, equol and the menopausal symptoms in Japanese women. J Jpn Menopause Soc. 2007;15:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jou HJ, Wu SC, Chang FW, Ling PY, Chu KS, Wu WH. Effect of intestinal production of equol on menopausal symptoms in women treated with soy isoflavones. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2008;102:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uesugi S, Watanabe S, Ishiwata N, Uchara M, Ouchi K. Effects of isoflavone supplements on bone metabolic markers and climacteric symptoms in Japanese women. Biofactors. 2004;22:221–228. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520220145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang M-H, Norris J, Han W, et al. Development of an updated phytoestrogen database for use with the SWAN Food Frequency Questionnaire: intakes and food sources in a community-based, multiethnic cohort study. Nutr Cancer. 2012;64(2):228–44. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2012.638434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hoey L, Rowland IR, Lloyd AS, Clarke DB, Wiseman H. Influence of soya-based infant formula consumption on isoflavone and gut microflora metabolite concentrations in urine and on faecal microflora composition and metabolic activity in infants and children. Br J Nutr. 2004;91:607–16. doi: 10.1079/BJN20031083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rafii F, Davis C, Park M, Heinze TM, Beger RD. Variations in metabolism of the soy isoflavonoid daidzein by human intestinal microfloras from different individuals. Arch Microbiol. 2003;180:11–16. doi: 10.1007/s00203-003-0551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Karr SC, Lampe JW, Hutchins AM, Slavin JL. Urinary isoflavonoid excretion in humans is dose dependent at low to moderate levels of soy-protein consumption. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:46–51. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Avis NE, Stellato R, Crawford S, et al. Is there a menopausal syndrome? Menopausal status and symptoms across racial/ethnic groups. Soc Sci Med. 2001 Feb;52(3):345–356. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Guttuso T, Jr, Evans M. Minimum trial duration to reasonably assess long-term efficacy of nonhormonal hot flash therapies. J Women’s Health(Larchmt) 2010;19(4):699–702. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]