Abstract

Introduction

The Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (HDSI) was designed as an instrument for the screening of hypersexuality by the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5 taskforce.

Aim

Our study sought to conduct a psychometric analysis of the HDSI, including an investigation of its underlying structure and reliability utilizing Item Response Theory (IRT) modeling, and an examination of its polythetic scoring criteria in comparison to a standard dimensionally-based cutoff score.

Methods

We examined a diverse group of 202 highly sexually active gay and bisexual men in New York City. We conducted psychometric analyses of the HDSI, including both confirmatory factor analysis of its structure and item response theory analysis of the item and scale reliabilities.

Main Outcome Measures

We utilized the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory.

Results

The HDSI adequately fit a single-factor solution, although there was evidence that two of the items may measure a second factor that taps into sex as a form of coping. The scale showed evidence of strong reliability across much of the continuum of hypersexuality and results suggested that, in addition to the proposed polythetic scoring criteria, a cutoff score of 20 on the severity index might be used for preliminary classification of HD.

Conclusion

The HDSI was found to be highly reliable and results suggested that a unidimensional, quantitative conception of hypersexuality with a clinically relevant cutoff score may be more appropriate than a qualitative syndrome comprised of multiple distinct clusters of problems. However, we also found preliminary evidence that three clusters of symptoms may constitute an HD syndrome as opposed to the two clusters initially proposed. Future research is needed to determine which of these issues are characteristic of the hypersexuality and HD constructs themselves and which are more likely to be methodological artifacts of the HDSI.

Keywords: hypersexual disorder, gay and bisexual men, sexual compulsivity, item response theory, confirmatory factor analysis

Introduction

Hypersexual disorder (HD) is a newly proposed construct that was under consideration for inclusion in the American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-5 as a non-paraphilic sexual disorder for the clinical diagnosis of excessive sexual thoughts and behaviors accompanied by clinically significant distress.1 Although research on HD is still in its infancy, similar constructs such as sexual compulsivity (SC) have been researched more extensively. Similar to HD, SC is characterized by “sexual fantasies and behaviors that increase in intensity and frequency over time so as to interfere with personal, interpersonal, or vocational pursuits.”2–9 These sexual issues are regarded as a growing problem in the United States and have received considerable attention from clinicians and researchers about their prevalence,2,4,10–12 comorbidity with psychiatric and substance use disorders,1,3,13–18 and associated health risks such as HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).5,6,9,19–28

Estimates indicate that rates of hypersexuality are higher among gay and bisexual men (GBM) compared to heterosexual men, ranging from 14–28% among community samples.8,29–32 Although not the defining features of hypersexuality, high frequency of sexual behavior and high numbers of sexual partners are common and often associated with marathon sex, recent STI incidence, lower condom self-efficacy, and lower likelihood of HIV status disclosure, which have been reported as typical experiences of GBM experiencing hypersexuality.6,19,22–28 The proposal to include HD as a distinct diagnosis in the DSM-5 is in response to these data, with proponents arguing for a need to have a unified operational definition with a common set of diagnostic criteria for clinicians who treat individuals seeking mental health care for HD-related symptomology.1

The proposed classification of HD has been met with controversy due to concerns about the validity of labeling sexual thoughts, practices and behaviors as pathological without considering the various contexts in which they are situated.33–38 Concern has been expressed by some about the utility of making a clinical diagnosis that they perceive as being based solely on level of sexual activity, given the wide variability in frequency and types of sexual practices people engage in, as well as a lack of consensus about what constitutes a healthy sexual appetite or lifestyle.33–38 Thus, it is important to establish good operational criteria for HD and to develop psychometrically-sound measures as clinical tools to diagnose and treat individuals seeking care for distress and other psychosocial adverse consequences resulting from excessive sexual thoughts and behaviors.

In a seminal review of the empirical data on hypersexual behavior, Kafka argued that the operational criteria for HD should be defined in such a way that encompasses the available evidence across the various theoretical dimensions studied (i.e., impulsivity, compulsivity, addiction).1 In doing so, HD can better serve as a diagnostic designation for this condition in spite of efforts to identify the presentation of symptoms as a behavioral addiction or comprised of features of impulse control or compulsivity disorder.1 The term hypersexual was chosen because it is thought to be the most atheoretical term that can best characterize this phenomenon as an increased intensity or frequency of normophilic sexual behaviors.36 Thus, HD has been defined as “a repetitive and intense preoccupation with sexual fantasies, urges, and behaviors, leading to adverse consequences and clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning”39 (p. 30; also see Kaplan & Krueger, 2010 for a review on the various HD subtypes36).

Although the board of the American Psychiatric Association ultimately decided not to include HD in the DSM-5,40 the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (HDSI) was the measure proposed for the clinical screening of HD by the DSM-5 work group.41 Reid and colleagues have recently demonstrated the validity and inter-rater reliability of the HD syndrome within a clinical sample utilizing a clinician-administered diagnostic interview.42 Given that the HDSI has not yet been utilized in nonclinical samples and that the utility of HD as a diagnostic taxon remains in question, research is needed regarding the psychometric properties and their implications for hypersexuality itself, particularly among individuals who engage in similar levels of sexual activity that may place them at higher risk for experiencing problematic hypersexuality.43 Further, questions remain regarding whether HD is best viewed as a quantitative, dimensional disorder differing in degree or a qualitative syndrome in which people experience multiple distinct patterns of symptoms.44 As such, it remains important to determine whether the assessment of hypersexuality is best assessed utilizing a continuous score with an established cutoff indicative of severity of symptomology or a scoring guide based on endorsement of distinct patterns of symptomology.

We conducted a psychometric analysis of the HDSI, including an investigation of its underlying dimensional structure and reliability utilizing Item Response Theory (IRT) modeling, and an examination of its polythetic scoring criteria in comparison to a standard dimensionally-based cutoff score. These analyses were conducted using data from a sample of highly sexually active GBM recruited in New York City. IRT modeling offers a strong technique for examining how well a measure captures the underlying latent construct that it purports to measure,45,46 and can be used to examine the reliability of each item on the HDSI in identifying and distinguishing individuals across the underlying continuum of hypersexuality.47

Method

Analyses for this paper were conducted on data from The Pillow Talk Project, a study of highly sexually active GBM in New York City (NYC). The primary goal of the study was to enroll GBM who are similar with regard to number of casual sexual partners but who differ in the extent to which their sexual thoughts and behaviors are causing problems in their lives – the defining feature of HD. Project enrollment is ongoing and analyses for this paper focused on the first 202 men enrolled in the project.

Participants and Procedures

Beginning in February of 2011, we enrolled participants utilizing the following recruitment strategies: 1) respondent-driven sampling; 2) internet-based advertisements on social and sexual networking websites; 3) email blasts through NYC sex party listservs; and 4) active recruitment in NYC venues such as gay bars/clubs and sex parties. Potential participants completed a phone-based screening interview to assess preliminary eligibility, which was defined as: 1) at least 18 years of age; 2) biologically male and self-identified as male; 3) nine or more male sexual partners in the prior 90 days, with at least 2 in the prior 30 days; 4) self-identification as gay, bisexual, or some other non-heterosexual identity (e.g., queer); and 5) daily access to the Internet in order to complete Internet-based assessments. We operationalized highly sexually active as having at least 9 male sexual partners in the 90 days prior to enrollment based on prior research with both community-based and probability-based samples of MSM.5,26,48–50 Sexual partners were defined as any partner with whom the participant engaged in sexual activity that had the potential to lead to orgasm.

Participants who met preliminary eligibility were emailed a link to an Internet-based computer-assisted self-interview (CASI), which included informed consent procedures. Men completed a one-hour survey at home via the Internet, before being scheduled for an in-person baseline appointment. This paper focuses exclusively on the Internet-based CASI data. Final eligibility was determined at the in-person appointment, with sexual partner criteria confirmed using a timeline follow-back (TLFB) interview. Only GBM confirmed eligible at the in-person baseline were included in the current analyses. GBM were excluded if, at the baseline interview, they demonstrated evidence of serious cognitive or psychiatric impairment that would interfere with their participation or limit their ability to provide informed consent. Overall, 79% of participants who pre-screened over the phone were eligible for the study, and of those, 62% completed an in-person appointment and enrolled into the study. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the City University of New York.

Measures

Demographics

Participants were asked to report several demographic characteristics including sexual identity, age, race/ethnicity, educational background, and relationship status. Participants self-reported their HIV status in the Internet survey. Men who reported being HIV-positive were asked to provide proof of their HIV status during their in person baseline appointment, and men who reported being HIV-negative or status unknown received a free, confidential, rapid HIV test as part of their baseline appointment. Three participants received a preliminary HIV positive result and were referred for confirmatory testing and linkage to care – data from these three participants were not included in these analyses.

Hypersexual disorder

Participants completed the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (HDSI), a measure developed by the DSM-5 Workgroup committee41 that consists of a total of 7 items split into two sections. Respondents reported based on the prior 6 months. Section A consists of five items measuring recurrent and intense sexual fantasies, urges, and behaviors, and Section B contains two items measuring distress and impairment as a result of these fantasies, urges, and behaviors (see Table 1). For each of the two blocks, which were displayed separately, participants were instructed to, “Please rate how often each item is true or how accurately it describes your sexual behavior during the last 6 months”. Responses were scored from 0 (Never true) to 4 (Almost always true) and were summed to provide a dimensional severity index score ranging from 0 to 28. No threshold for the severity index has been proposed as being diagnostically informative for the scale. Polythetic diagnostic criteria have been proposed that require recoding responses into dichotomies whereby responses of 3 or 4 are coded as endorsement and all others are coded as non-endorsement. Following the recoding, a a preliminary positive screening for HD has been operationalized as the endorsement of at least four items in section A and at least one item in section B.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for HDSI Item Responses

| Item | Median Response | IQR |

|---|---|---|

| A1. I have spent a great amount of time consumed by sexual fantasies and urges as well as planning for and engaging in sexual behavior | 3.0 | 2.0 – 3.0 |

| A2. I have used sexual fantasies and sexual behavior to cope with difficult feelings (for example, worry, sadness, boredom, frustration, guilt, or shame) | 2.0 | 2.0 – 3.0 |

| A3. I have used sexual fantasies and sexual behavior to avoid, put off, or cope with stresses and other difficult problems or responsibilities in my life | 2.0 | 2.0 – 3.0 |

| A4. I have tried to reduce or control the frequency of sexual fantasies, urges, and behavior but I have not been very successful | 2.0 | 1.0 – 3.0 |

| A5. I have continued to engage in risky sexual behavior that could or has caused injury, illness, or emotional damage to myself, my sexual partner(s), or a significant relationship | 2.0 | 1.0 – 3.0 |

| B1. Frequent and intense sexual fantasies, urges and behavior have made me feel very upset or bad about myself (for example, feelings of shame, guilt, sadness, worry, or disgust) or I tried to keep my sexual behavior a secret | 2.0 | 1.0 – 3.0 |

| B2. Frequent and intense sexual fantasies, urges and behavior have caused significant problems for me in personal, social, work, or other important areas of my life | 1.0 | 1.0 – 2.0 |

Note. N = 202. IQR = Interquartile Range.

Although it is not a primary focus of this manuscript, an ddditional section of the scale includes an assessment of which types of behaviors are causing the problems assessed in sections A and B. When provided with a set list of behaviors, the average number of problematic behaviors reported by participants was 3.9 (Mdn = 3.0, SD = 2.2, IQR = 2.0 – 6.0). A majority (80%) of participants reported problems with sexual behavior with consenting adults and nearly half experienced problems with masturbation (48.5%) and pornography (49.0%). Approximately one-third experienced problems with cybersex (32.3%), phone or text message sex (28.2%), adult bookstores or video booths (30.2%), bathhouses (30.2%), sex parties (36.6%), and public cruising (38.1%). Using a free-response option, 18 men indicated other problems, most of whom (n = 10) described difficulties with searching or “cruising” for partners on the internet or mobile phone “apps.” A follow-up version of the scale is available for completion by those who screen positive on the HDSI. This version assesses symptoms within the prior two weeks. Only sections A and B of the HDSI were included in these analyses.

Data Analysis Plan

We utilized four broad analytic procedures: (1) descriptive examination of item endorsement and bivariate associations with screening positive on the HDSI; (2) examination of factor structure of the HDSI; (3) IRT analyses of the HDSI; and (4) an examination of potential cutoff scores for the dimensional severity index.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate associations

Because item responses were considered ordinal, we calculated the median response and the interquartile range (IQR) of responses for each of the seven HDSI items. We then examined demographic differences by classification on the HDSI. Next, we conducted a series of analyses to examine the association between endorsement of each individual item and screening positive for HD based on the proposed scoring criteria. First, we calculated the percentage of men who screened negative for HD and endorsed each item. These values are equal to 1 minus specificity and those close to 0% suggest that an item has good specificity (i.e., men who screened negative were unlikely to endorse the item). Second, we calculated the percentage of men who screened positive for HD and endorsed each item. Values close to 100% suggest that an item has good sensitivity for distinguishing HD (i.e., men who screened positive were likely to endorse the item).

In a third analysis we aggregated the two prior percentages and calculated the number of men who endorsed the item and screened positive for HD. If both sensitivity and specificity were high, this number would be similarly high – a sensitivity and specificity of 100% each (or 0% when using 1 minus specificity) would yield a 100% on this index (i.e., all men who did not endorse the item screened negative for HD and all men who did endorse the item screened positive).

Examination of factor structure

Factor analyses were conducted for two purposes. First, we sought to statistically examine the existence of two related but distinct areas that were proposed to constitute hypersexuality as measured by the HDSI – “recurrent and intense sexual fantasies, sexual urges, and sexual behavior” (Section A) and “clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning” (Section B).1 We utilized confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to compare the proposed polythetic two-factor syndrome underlying the HDSI with a single-factor alternative. Evidence for the latter would suggest a single dimension comprises hypersexuality. Results are presented using the ordinal response options rather than the dichotomous indicators of item endorsement, though results were consistent regardless of how the items responses were coded.

Second, factor analysis was used to test the two primary assumptions of unidimensional IRT models. Specifically, the assumption is that a single latent construct is responsible for the patterns of responses to the scale items and, after adjusting for the variance resulting from the latent construct, the responses to the scale items are independent of each other (i.e., the assumption of local independence). In other words, these assumptions are that the items are all measuring the same construct, and that this construct is the only construct they share in common. To examine assumptions of local independence, we calculated the residual correlation matrix from CFA. Any residual correlations between two items that exceed the absolute value of .20 were considered indicative of local dependence. An examination of the assumption of unidimensionality was done based on the results of a CFA in which a single factor was specified and an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Within the CFA, we examined standard indicators of model fit,47,51–56 which included comparative fit index (CFI) greater than 0.95, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than 0.06, Tucker Lewis index (TLI) greater than 0.95, and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) less than 0.08. We next conducted an EFA in order to obtain estimates of the factor eigenvalues and percent of variance accounted for by each factor. The first factor having an eigenvalue that is at least 4 times greater than that of the second factor and accounting for at least 20% of the variance were considered evidence for unidimensionality.57

All factor analyses were conducted using Mplus software version 6.12 using weighted least squares estimation. All factor indicators (HDSI items) were specified as ordered categorical variables. Modification indices were requested for CFA models. Comparisons of nested models were conducted using the DIFFTEST option which produces chi-square statistics of change in model fit in which a statistically significant result suggests the more restricted model (that with higher degrees of freedom) is a significantly worse fit to the data, while a non-significant result suggests improvement in model fit with the added restrictions.

Item response theory analyses

We modeled participants’ responses to the seven HDSI items using Samejima’s polytomous graded response model.58 In classical approaches to reliability, a signal reliability estimate is made for across levels of the trait being measured. This approach obscures the fact that scales often are more reliable at some levels of trait than others. In contrast, IRT methods estimate the precision of individual items and the scale as a whole across all levels of the trait being measured. We conducted IRT analyses using IRTPRO version 2.1.59 Fit statistics provided from this software package are S-χ2, which are Pearson χ2-based fit statistics that express the degree of fit or misfit between observed and expected values in the data.59

Alternative scoring analyses

The last set of analyses were intended to follow-up on the question of whether the scale showed evidence of unidimensionality by examining two different methods for obtaining screening results. Specifically, we examined whether the polythetic scoring criteria (based on experiencing two distinct types of symptoms) differed from using a standard cutoff on the dimensional severity score index (indicating greater overall distress across items). Establishing correspondence between the dimensional score and the polythetic scoring criteria would suggest that individual differences in hypersexuality might exist along a continuum rather than being a syndrome comprised of different kinds of symptoms.44 To examine this, we conducted receiver operating curve (ROC) analyses. These analyses take each point on a scale as a potential cutoff and compare them with a dichotomous outcome in order to produce sensitivity and specificity statistics for each – in this case, we were comparing cutoff points for the dimensional score with overall screening results based on the polythetic scoring criteria. A cutoff score with sensitivity and specificity estimates that were close to 100% would suggest that the dimensional cutoff had strong correspondence with the polythetic scoring criteria.

Results

As can be seen in Table 2, the sample was demographically diverse with regards to several factors. We found several demographic differences in preliminary positive screening on the HDSI. We did not have sufficient variation within HDSI screening groups to examine differences across all racial/ethnic groups, but found that a significantly smaller portion of White men (15.8%, n = 18) than men of color (26.1%, n = 23) screened positive for HD, χ2(1) = 3.29, p = .05. Similarly, a higher proportion of HIV-positive (30.9%, n = 25) than HIV-negative (13.2%, n = 16) screened positive for HD, χ2(1) = 9.33, p = .002. There were differences by educational attainment – 43.5% (n = 10) of men with a high school degree or less screened positive for HD, compared with 21.3% (n = 13) of those with some college or an Associate’s degree, 15.2% (n = 10) of those with a 4-year college degree, and 15.4% (n = 8) of those with a graduate degree, χ2(3) = 9.54, p = .02. Among these highly sexually active GBM, we found marginally significant differences between the proportion of men who were in a relationship (30.2%, n = 13) and those who were not (17.6%, n = 28) who screened positive for HD, χ2(1) = 3.33, p = .06. We found no differences in HD screening by employment status and there was insufficient variation in sexual orientation for statistical comparison. Men who screened positive and negative for HD did not differ in terms of average age.

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| Black | 33 | 16.3 |

| Latino | 30 | 14.9 |

| White | 114 | 56.4 |

| Asian/Native Haw./Pac. Islander | 4 | 2.0 |

| Multiracial/Other | 16 | 7.9 |

| Other/Unknown | 5 | 2.5 |

| HIV Status | ||

| Negative | 121 | 59.9 |

| Positive | 81 | 40.1 |

| Sexual Orientation | ||

| Gay, queer, or homosexual | 172 | 85.6 |

| Bisexual | 24 | 11.9 |

| Other non-heterosexual identity | 6 | 2.5 |

| Employment Status | ||

| Full-time | 70 | 34.7 |

| Part-time | 50 | 24.8 |

| On disability | 23 | 11.4 |

| Student (unemployed) | 18 | 8.9 |

| Unemployed | 41 | 20.3 |

| Highest Educational Attainment | ||

| High school diploma/GED or less | 23 | 11.4 |

| Some college or Associate’s degree | 61 | 30.2 |

| Bachelor’s or other 4-year degree | 66 | 32.7 |

| Graduate degree | 52 | 25.7 |

| Relationship Status | ||

| Single | 159 | 78.7 |

| Partnered | 43 | 21.3 |

| M | SD | |

|

|

||

| Age | 37.03 | 11.35 |

Note. N = 202.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate associations

The seven items on the HDSI displayed variability in their typical response patterns (Table 1). Item A1 had the highest median response, while item B2 had the lowest median response. All other items had consistent median responses at the midpoint of the scale. Item A1 had a median of three and item B2 had a median of one, and both had IQRs that spanned two points. All other items had medians of two, with items A2 and A3 having IQRs that spanned two points and items A4, A5, and B1 having IQRs that spanned three points. These findings provide preliminary evidence that the scale had items that tapped into different levels of severity of hypersexuality.

The first set of analyses displayed in Table 3 focused on the associations between the items themselves and screening results on the HDSI using the proposed scoring algorithm. We found that only one item had a specificity value of at least 90%. Only 6.21% of men who were screened negative for HD endorsed item B2, suggesting it accurately discriminated nearly 94% of non-HD men correctly. This suggests that it was uncommon for men who screened negative for HD to endorse this item. Several items had specificity values below 70% – more than one-third of men who screened negative for HD endorsed items A1, A2, and A3. Conversely, these three items had high sensitivity. All men who screened positive for HD endorsed items A2 and A3, and all but 3 (92.68%) endorsed item A1. This suggests that men who screened positive for HD were highly likely to endorse these items. All other items performed fairly well, with the lowest sensitivity value being 73.17%.

Table 3.

Bivariate Associations between Item Endorsement and HDSI Classification

| Item | HDSI Clasification

|

% Classified of Endorsed

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 161)

|

Yes (n = 41)

|

||||

| n | %a | n | %b | ||

| A1. Endorsed | 67 | 41.61 | 38 | 92.68 | 36.19 |

| A2. Endorsed | 59 | 36.65 | 41 | 100.00 | 41.00 |

| A3. Endorsed | 52 | 32.30 | 41 | 100.00 | 44.09 |

| A4. Endorsed | 23 | 14.29 | 30 | 73.17 | 56.60 |

| A5. Endorsed | 41 | 25.47 | 35 | 85.37 | 46.05 |

| B1. Endorsed | 23 | 14.29 | 36 | 87.80 | 61.02 |

| B2. Endorsed | 10 | 6.21 | 31 | 75.61 | 75.61 |

| Block A Criteria Met | 10 | 6.21 | 41 | 100.00 | 80.39 |

| Block B Criteria Met | 26 | 16.15 | 41 | 100.00 | 61.19 |

Note.

This value is the percentage of men who were not classified as hypersexual who endorsed each item (this is equal to 1 – specificity).

This value is the percentage of men who were classified as hypersexual who endorsed each item (this is equal to sensitivity).

There was substantial variation in the correspondence between individual item endorsement and screening results on the HDSI. For the most part, endorsement of individual items in Block A was not strongly associated with screening outcomes – values ranged from 36% to 56% of men endorsing each item who screened positive for HD. On the other hand, Item B2 performed quite well, with nearly 76% of people endorsing item B2 screening positive for HD. With regards to the two blocks of items proposed, 80% of men who met criteria for Block A screened positive for HD, while only 61% of men who met criteria for Block B screened positive for HD. As a result of the scoring criteria, both Blocks A and B had perfect sensitivity, while Block A’s higher specificity led to its better overall performance.

Examination of factor structure

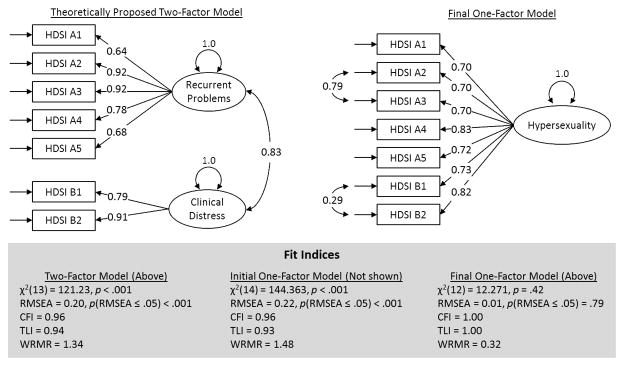

We present the standardized (using the Mplus STDYX standardization) results of the CFA in Figure 1. The two-factor model had only one fit index (CFI > .95) that exceeded the standards for evidence of good fit, and the correlation between the two factors also was quite high. We subsequently tested a single-factor model and found that the restriction of one factor significantly worsened model fit, χ2(1) = 25.75, p < .001. However, upon examining the results for the single factor model, we found evidence for a residual correlation between items A2 and A3. As a result of these findings, we subsequently tested two models – a three factor model (items A1, A4, and A5 on the first factor, items B1 and B2 on the second factor, and items A2 and A3 on a the third factor) and a single-factor solution allowing the residual covariance between items A2 and A3 and items B1 and B1 to be freely estimated. The single factor solution with residual covariances did not differ significantly from the three factor model (not shown), χ2(1) = 1.49, p = .22, suggesting that the more restricted single factor solution was a better fit to the data. As can be seen in Figure 1, the residual covariance between items A2 and A3 is quite high (and both residual covariances were statistically greater than 0), suggesting that the association between these items was greater than the covariance estimated through a single latent factor. The residual correlation in items A2 and A3 was a result of significant overlap in the endorsement of the two items – 33% responded differently to one item than the other, but only 3.9% (n = 8) of these differences were greater than one unit. This overlap is likely to be a result of the content of each item (see Table 1), which refers to using sex as a means of coping.

Figure 1.

Above are the results of a series of three confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) of the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory. In the first model, we tested the proposed structure of the HDSI as consisting of two clusters of symptoms using a two-factor model in which the factors were allowed to correlate. Next, a single-factor model was tested to examine whether a unidimensional model was a better fit to the data. Results from the single-factor model suggested that a single-factor model had similar fit to the two-factor model, but that two items (A2 and A3) shared a highly significant amount of residual covariance, which was freed and estimated within the final model.

Figure 1 displays several fit indices for the one-factor model without allowing for a residual correlation between items A2 and A3. As the figure indicates, this model had poor fit. As described above, accounting for the residual covariation between two pairs of items led to excellent fit of the unidimensional model across all presented indicators. Given that the residual covariation provides evidence that local independence was violated for the two pairs of items, we explored this issue further within the IRT analyses. We conducted EFA using Mplus to confirm that the assumption of unidimensionality had been adequately met for IRT analyses. The first factor extracted had an eigenvalue of 4.15, which was nearly five times as large as the eigenvalue of 0.87 for the second factor. In all, the first factor accounted for 59.2% of the total variation. The results of the EFA supported the notion that sufficient unidimensionality was present within the scale to conduct IRT analyses.57 In contrast to the hypothesized structure of the scale and in line with the results of the CFA, the second factor extracted from the EFA consisted of items A2 and A3 with a correlation of 0.63 with the first factor.

Item response theory analyses

Each of the 7 HDSI items performed well in the analyses using an alpha threshold of .01. The p-values associated with the S-χ2 fit statistics ranged from 0.06 to 0.88, with an average p-value of 0.38 (See Table 4). The final model itself also had adequate fit, with a RMSEA statistic of 0.05. The software also provided some classical test theory statistics, such as the Cronbach’s alpha, which was calculated to be 0.88 for the full scale. Estimates indicated that this estimate of internal consistency would not be improved by the removal of any scale items. With regards to the assumption of local independence, the CFA indicated a significant residual correlation between items A2 and A3 as well as B1 and B2. The IRT analyses produced an LD (i.e., local dependence) statistic60 of 9.9 for items A2 and A3, which falls just below the threshold of 10 used to indicate some violation of local independence, but was low enough to proceed with analyses (the LD statistic of 0.7 for B1 and B2 was low).

Table 4.

Item Response Theory-based parameter estimates and fit statistics for HDSI Items

| Item | Parameter Estimates

|

S-χ2

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope | Threshold 1 | Threshold 2 | Threshold 3 | Threshold 4 | χ2 | p-value | |

| A1 | 1.63 | 4.37 | 2.52 | 0.12 | −2.20 | 51.27 | 0.18 |

| A2 | 2.54 | 4.32 | 2.32 | −0.01 | −2.72 | 37.99 | 0.52 |

| A3 | 2.60 | 4.22 | 2.21 | −0.28 | −2.91 | 52.39 | 0.06 |

| A4 | 2.30 | 2.86 | 0.34 | −1.77 | −4.12 | 29.77 | 0.88 |

| A5 | 1.67 | 2.33 | 0.60 | −0.72 | −2.35 | 52.41 | 0.34 |

| B1 | 1.80 | 2.43 | 0.58 | −1.28 | −3.75 | 46.92 | 0.35 |

| B2 | 2.38 | 2.15 | −0.45 | −2.35 | −4.94 | 37.84 | 0.34 |

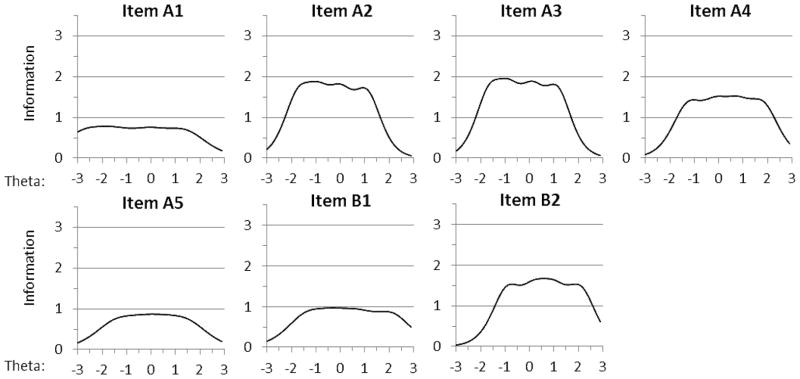

Raw values for slopes and thresholds can be difficult to interpret and are represented graphically in the 7 corresponding item information curves presented in Figure 2. These plots graphically display the amount of information – an IRT term for reliability or precision of measurement – across the continuum of the latent construct, which is referred to as theta and corresponds to the underlying latent trait of hypersexuality. As is common with latent variable modeling software, the latent construct is centered such that its mean is 0 and its standard deviation is one – the plots display values of theta ranging from 3 standard deviations above and below the mean. As can be seen, items A2, A3, A4, and B2 peak at higher levels of information than the other three items. However, it is important to note that some items provide more precision at lower or higher levels of theta than others. For example, item A1 does not provide as much information as other items, but it provides more information for values of theta between −3 and −2 than any other item, making it a useful item for measuring and differentiating those with the lowest levels of hypersexuality. Similarly, items B1 and B2 provide more precision from theta values ranging from 2 to 3, making them better suited to distinguish men with the highest levels of hypersexuality.

Figure 2.

Above are the 7 IRT-based item information curves for the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory. The horizontal axes display the values of theta (the value of the latent construct) ranging from −3 to 3. The vertical axes display the range of item information from 0 to 3.5, which indicates how precisely each item measures the construct (i.e., hypersexuality). Each individual plot shows how much information each item contributes to the scale across the possible values of theta.

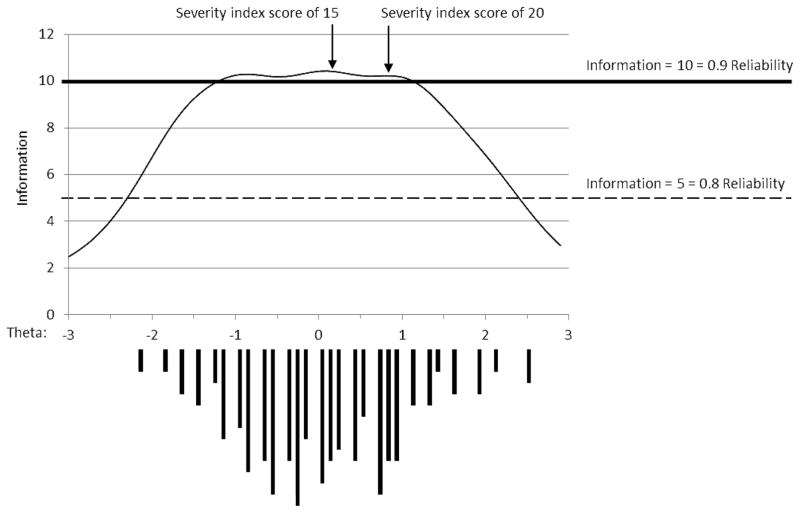

In addition to providing information regarding the contribution of each item on a scale, the IRT analyses provide useful diagnostics for the HDSI scale on the whole. Figure 3 displays the test information curve in the upper portion of the plot. Test information is the sum of information across all items. The test information curve displays the full scale’s information function across the range of the latent construct. The test information curve is shown with two reference lines through it – a test information value of 5 corresponds with a reliability estimate of 0.80 demonstrating good reliability, and a value of 10 corresponds with a reliability estimate of 0.90 suggesting excellent reliability. As can be seen in the plot, the scale measures with at least 90% reliability from theta values of −1.2 to 1.1, which can be converted to corresponding severity index scores of 6 through 22. Similarly, the scale measures hypersexuality with at least 80% reliability across the range of theta values from −2.3 to 2.4, corresponding with severity index scores of 1 to 27. This suggests that the HSDI has less than 80% reliability at only the lowest and highest possible values on the severity index (i.e., 0 and 28). It is worth noting that the minimum severity score that one can receive and screen positive for HD using the proposed scoring criteria is a score of 15 – no severity score threshold has been established, but based on the scoring criteria, a person must endorse at least 5 total items at a score of 3 or higher to qualify for classification. As can be seen in Figure 3, the scale demonstrated strong measurement reliability at this severity index, suggesting it is well-suited for making distinctions between those with slightly lower and slightly higher levels of hypersexuality in this region of the construct. The lower portion of Figure 3 shows that the distribution of scores across the latent construct was relatively normal and was well-distributed from values of theta from −2.0 to 2.0.

Figure 3.

Above is the IRT-based test information curve for the Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory. The horizontal axis displays the values of theta (the value of the latent construct) ranging from −3 to 3. The vertical axis for the upper portion of the plot displays the range of test information from 0 to 12, which indicates how precisely the test measures the latent construct (hypersexuality). For values of theta between −2.3 and 2.4, the scale measures with at least 80% reliability; for values of theta between −1.2 and 1.1, the scale measures with at least 90% reliability (corresponding to severity index scores of 6 to 22). The lower portion of the plot is a histogram that shows the observed distribution of scores within the sample across the continuum of hypersexuality; this shows that the sample had adequate observed variability across much of the continuum from −2.0 to 2.0.

Alternative scoring analyses

The final analysis estimated whether a quantitative view of hypersexuality based on the dimensional score would provide similar results to the more qualitative, polythetic criteria proposed for scoring the HDSI. We compared potential cutoff points on the dimensional score for the HDSI with the screening results of its proposed polythetic scoring criteria. The results of the ROC analyses suggested that there were three potential cutoff values for the dimensional HDSI severity index scores that had high levels of consistency with the polythetic scoring criteria in predicting HD. Although it is typical to display the actual curve produced by the analysis, in this case it almost exclusively followed either the leftmost or topmost axis as a result of its adequacy of prediction and it is not presented. A cutoff of 19 or higher on the severity score was associated with perfect (100%) sensitivity and high (89%) specificity in predicting classification based on the polythetic scoring criteria. Using a cutoff of 20 or higher produced similarly high sensitivity (95%; i.e., 5% rate of false-negatives) and specificity (96%; i.e., a 4% rate of false-positives). A cutoff of 21 or higher produced lower sensitivity (78%) but higher specificity value (98%) – specificity was maximized by using a cutoff of 22 or higher (specificity = 100%), but this compromised the sensitivity value considerably (61%). As can be seen in Figure 3, the scale demonstrated strong reliability of measurement throughout this range of potential cutoff scores within the IRT analyses, suggesting it is well suited to make fine distinctions at these levels of hypersexuality.

For the purposes of this scale, the cutoff of 20 corresponded almost perfectly with the polythetic scoring criteria (it had 95% sensitivity and 96% specificity). In situations where a quantitative, dimensional view of hypersexuality is more desirable than a qualitative, polythetic approach, a score of 20 appeared to be the best potential cutoff value for establishing a positive screening for hypersexuality. Using the cutoff of 20 compared to the proposed scoring algorithm, only 4% (n = 8) of participants were misclassified, 2 of whom were falsely classified as screening negative for HD and 6 of whom were falsely classified as screening positive.

Discussion

Our study was the first to examine the reliability of the HDSI as a diagnostic measure for HD in a community-based sample of highly sexually active GBM. We sought to assess the factor structure of the HDSI and to conduct IRT modeling to test the HDSI’s ability to measure the construct it purports to measure, namely HD. The investigation of this construct and its accompanying diagnostic instrument was critical given the decision to exclude HD from the DSM-5 and the need for ongoing research about the condition and its assessment. We found that the prevalence of screening positive on the HDSI was approximately 20% in a sample of highly sexually active GBM when using the proposed polythetic scoring criteria, as well as when using an alternative to the polythetic scoring criteria – a simple cutoff of 20 on the severity score index.

EFA and CFA indicated sufficient unidimensionality for the IRT analysis, although two of the items seemed to have the potential to be extracted as a separate factor. Statistically, the two items measuring sex as a form of coping (A2 and A3) appeared to measure an additional construct beyond the general factor of hypersexuality. However, these two items were not those which were proposed by the authors of the HDSI to form a distinct symptom block (i.e., items B1 and B2) and therefore, our analyses did not garner support for the two distinct symptom blocks as has been proposed (Sections A and B). It is worth noting that there was evidence suggesting that items A2 and A3 as well as items B1 and B2 might each tap into distinct clusters of symptoms from those of the other items. Based on these data, we believe that there is evidence that more than two subtypes of symptomology might be prevalent. In other words, in addition to the two proposed clusters of symptoms (Section A and B), the use of sex as a coping mechanism could be a third subtype of potential importance. However, we ultimately found that a one factor solution that allowed for association among two pairs of items was a better fit to the data than a three factor solution. More work is needed to determine whether hypersexuality is best characterized as the experience of any of these negative aspects of sexuality (which overlapped highly in their co-occurrence among this sample), or whether subtypes of hypersexuality exist that are characterized differently by the experience of these different types of symptomology.

Results of the IRT modeling showed that the HDSI items performed with high precision along nearly the entire HD continuum. Item information curves indicated that all of the items provided important information across the continuum and that each was precise at specific levels of the hypersexual continuum (low end vs. high end). Internal consistency of the HDSI was high and comparable to that found in a sample of patients who sought treatment for HD.42 Overall, the scale demonstrated good precision in distinguishing between those with lower and higher levels of hypersexuality across the clinical range of the scale; that is, the range that is consistent with the proposed polythetic scoring criteria. Results of analyses suggested that classification with the scale was nearly identical regardless of whether the polythetic scoring criteria were used or a simple cutoff on the continuous severity index. A cutoff score of 20, for example, would classify all but eight participants in the exact same way as the more qualitative, block-based endorsement criteria proposed for the instrument. These findings indicate that, when operationalized using the HDSI with a sample of highly sexually active GBM, there was no evidence that hypersexuality is better measured as consisting of the presence of distinct blocks of symptoms than as high levels of symptoms overall. However, given that the second block of symptoms contains only two items on the measure (compared with five in the first block), this may be at least partially an artifact of the measure itself.

We found that individual items on the HDSI had differing levels of correspondence with the results of the screening instrument as a whole. Three of the HDSI items had sensitivity of 90% or higher in predicting whether or not individuals screened positive for hypersexuality, while only one item had specificity of 90% or higher. These findings suggest that the individual item endorsements were more consistent with the overall results of the screening inventory for men who screened positive than for those who screened negative for hypsersexuality. These findings were consistent with results of IRT analyses that suggested that some items tapped into less severe manifestations of hypersexuality while endorsement of others was typically only done by those who showed evidence of hypersexuality. Given that the proposed polythetic scoring criteria are based on the endorsement of individual items, these findings suggest that some items may influence the scoring criteria more than others.

Limitations

Despite the strengths of our analytic strategy for this study, there are several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Psychometric investigations typically compare a newly developed measure to an existing validated measures or a diagnostic “gold standard.” However, because the HDSI is proposed to be such a “gold standard,” we chose to investigate its psychometric properties with a focus on reliability rather than attempting to establish its diagnostic validity. The HDSI was designed to be a clinician diagnostic tool. However, we relied on self-report using an Internet-based survey. A clinician-administered version of the instrument would also allow for clarifications and follow-ups to confirm whether or not diagnostic criteria were met. Future studies are needed to examine the extent to which the self-administered version of the HDSI produces different results than one that is administered by another person, and particularly a trained clinician. Although a key strength of the study was the sample of highly sexually active GBM, this sample may be qualitatively different from other samples including other GBM who are not highly sexually active. We found some demographic differences in our analyses; however, we were limited by our sample size in conducting further analyses to determine whether these are the result of mean differences across groups or the presence of differential item functioning of the instrument. The current study findings are considered exploratory and continued replication is necessary in order to determine the stability of our findings across different samples.

Conclusion

Despite the limitations of the study, our findings indicate that the HDSI is a reliable instrument among a non-treatment seeking sample of GBM who are highly sexually active. Future research is needed to replicate the current findings in order to determine the stability of the IRT parameters derived from this sample, as well as from clinical and other community-based samples. Contrary to the proposed two-cluster syndrome underlying HD, we found preliminary support for either a unidimensional, quantitative conception of hypersexuality with a clinically relevant cutoff score or that three symptom clusters may underlie the HD syndrome. Such an underlying structure provides preliminary evidence for the scale’s utility as a self-report screening measure for HD with a potentially rapid scoring mechanism based on a single cutoff on a continuous symptom score. Future research is needed to determine which of these issues are characteristic of the hypersexuality and HD constructs themselves and which are simply methodological artifacts of the HDSI. Given the strong sensitivity and specificity of the cutoff scores we found in our investigation, the scale’s freely available nature for administration in clinical settings, and its extreme brevity, it would be useful for clinicians to administer the HDSI as a screening instrument. For GBM patients who express concerns about behaviors consistent with hypersexuality, the HDSI may serve as a useful self-administered tool for gaining a preliminary assessment of their condition. Clinicians have the option of using the polythetic scoring criteria or the newly proposed cutoff score range based on simply summing across the responses for the seven itsems. Such an assessment can serve as an indicator to the clinician that further assessment and possibly treatment are warranted. Additional studies are needed to establish the sensitivity of the measure to treatment effects so that it may be considered as a tool for monitoring treatment progress, which would also be useful in clinical practice. More research is also needed to examine the psychometric properties and particularly to examine the concurrent and discriminant validity of the HDSI in order to ensure its utility as a clinical diagnostic tool.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by a research grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH087714; Jeffrey T. Parsons, Principal Investigator). H. Jonathon Rendina was supported in part by a National Institute of Mental Health Ruth L. Kirchstein Individual Predoctoral Fellowship (F31-MH095622). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the Pillow Talk Research Team: Aaron Breslow, John Pachankis, Pedro Carneiro, Ruben Jimenez, and Sarit Golub. We would also like to thank CHEST staff who played important roles in the implementation of the project: Chris Hietikko, Fran Ferayorni, Joshua Guthals, Kailip Boonrai, Leniere Miley, and Michael Adams, as well as our team of research assistants, recruiters, and interns. Finally, we thank Chris Ryan, Daniel Nardicio, and Stephan Adelson and the participants who volunteered their time for this study.

References

- 1.Kafka MP. Hypersexual disorder: A proposed diagnosis for DSM-V. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39:377–400. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9574-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black DW. Compulsive Sexual Behavior: A Review. Journal of Practical Psychology and Behavioral Health. 1998;4:219–229. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carnes PJ. Sexual Addiction and Compulsion: Recognition, Tretment, and Recovery. CNS Spectrums. 2000;5:63–72. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900007689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman E. Is your patient suffering from compulsive sexual behavior? Psychiatric Annals. 1992;22(6):320–325. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grov C, Parsons JT, Bimbi DS. Sexual compulsivity and sexual risk in gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39(4):940–949. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9483-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalichman SC, Rompa D. Sexual sensation seeking and sexual compulsivity scales: Reliability, validity, and predicting HIV risk behavior. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1995;65(3):586–601. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muench F, Parsons JT. Sexual Compulsivity and HIV: Identification and Treatment. Focus. 2004;19:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parsons JT, Kelly BC, Bimbi DS, Muench F, Morgenstern J. Accounting for the social triggers of sexual compulsivity. Journal of Addictive Diseases. 2007;26(3):5–16. doi: 10.1300/J069v26n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parsons JT, Grov C, Golub SA. Sexual compulsivity, co-occurring psychosocial health problems, and HIV risk among gay and bisexual men: Further evidence of a syndemic. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102(1):156–162. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carnes P. Don’t call it love: Recovery from sexual addiction. New York: Bantam Books; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodman A, et al. Sexual Addiction. In: Lowinson JH, Ruiz P, Millman RB, editors. Substance abuse: a comprehensive textbook. Philadelphia: Williams & Wilkins; 1997. pp. 340–354. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuzma JM, Black DW. Epidemiology, prevalence, and natural history of compulsive sexual behavior. Psychiatr Clin North Am Dec. 2008;31(4):603–611. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Black DW, Kehrberg LLD, Flumerfelt DL, Schlosser SS. Characteristics of 36 subjects reporting compulsive sexual behavior. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154(2):243–249. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kafka MP, Hennen J. A DSM-IV Axis I comorbidity study of males (n=120) with paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment. 2002;14:349–366. doi: 10.1177/107906320201400405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kafka MP, Prentky RA. Preliminary observations of DSM-III-R Axis I comorbidity in men with paraphilias and paraphilia-related disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1994;55:481–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morgenstern J, Muench F, O’Leary A, et al. Non-paraphilic compulsive sexula behavior and psychiatric co-morbidities in gay and bisexual men. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. 2011;18:114–134. doi: 10.1080/10720162.2011.593420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raymond NC, Coleman E, Miner MH. Psychiatric comorbidity and compulsive/impulsive traits in compulsive sexual behavior. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2003;44:370–380. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00110-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wines D. Exploring the applicability of criteria for substance dependence to sexual addiction. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. 1997;4:195–220. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benotsch EG, Kalichman SC, Kelly JA. Sexual compulsivity and substance use in HIV seropositive men who have sex with men: Prevalence and predictors of high-risk behaviors. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24(6):857–868. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dodge B, Reece M, Cole SL, Sandfort TGM. Sexual compulsivity among heterosexual college students. Journal of Sex Research. 2004;41(4):343–350. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dodge B, Reece M, Herbenick D, Fisher C, Satinsky S, Stupiansky N. Relations Between Sexually Transmitted Infection Diagnosis and Sexual Compulsivity in a Community-Based Sample of Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) Sex Transm Infect. 2007 Dec 20; doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.028696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalichman SC, Greenberg J, Abel GG. HIV-seropositive men who engage in high risk sexual behavior. Psychological characteristics and implications for prevention. AIDS Care. 1997;9(4):441–540. doi: 10.1080/09540129750124984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalichman SC, Johnson JR, Adair V, Rompa D, Multhauf K, Kelly JA. Sexual sensation seeking: scale development and predicting AIDS-risk behavior among homosexually active men. J Pers Assess Jun. 1994;62(3):385–397. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6203_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalichman SC, Rompa D. The sexual compulsivity scale: Further development and use with HIV-Positive persons. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2001;76:379–395. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7603_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’leary A, Wolitski RJ, Remien RH, et al. Psychosocial correlates of transmission risk behavior among HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men. AIDS. 2005;19:1–9. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000167353.02289.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parsons JT, Bimbi DS, Halkitis PN. Sexual compulsivity among gay/bisexual male escorts who advertise on the Internet. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2001;8:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reece M. Sexual compulsivity and HIV serostatus disclosure among men who have sex with men. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. 2003;10:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reece M, Plate PL, Daughtry M. HIV prevention and sexual compulsivity: The need for an integrated strategy of public health and mental health. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2001;8(2):157–167. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baum MD, Fishman JM. AIDS, sexual compulsivity, and gay men: A group treatment approach. In: Cadwell SA, Burnham RA Jr, editors. Therapists on the front line: Psychotherapy with gay men in the age of AIDS. Washington, DC, US: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1994. pp. 255–274. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper A, Delmonico DL, Burg R. Cybersex users, abusers, and compulsives: New findings and implications. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity. 2000;7:5–29. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kelly BC, Bimbi DS, Nanín JE, Izienicki H, Parsons JT. Sexual compulsivity and sexual behaviors among gay and bisexual men and lesbian and bisexual women. Journal of Sex Research. 2009;46:1–8. doi: 10.1080/00224490802666225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parsons JT, Severino JP, Grov C, Bimbi DS, Morgenstern J. Internet use among gay, bisexual, and MSM with compulsive sexual behavior. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. 2007;14:239–256. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balon R, Segraves RT, Clayton A. Issues for DSM-V: sexual dysfunction, disorder, or variation along normal distribution: toward rethinking DSM criteria of sexual dysfunctions. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164(2):198–200. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fong TW, Reid RC, Parhami I. Behavioral addictions: where to draw the lines? Psychiatric Clinics in North America. 2012;35(2):279–296. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halpern AL. The proposed diagnosis of hypersexual disorder for inclusion in DSM-5: unnecessary and harmful. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(3):487–488. doi: 10.1007/s10508-011-9727-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaplan MS, Krueger RB. Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of hypersexuality. Journal of Sex Research. 2010;47(2–3):181–198. doi: 10.1080/00224491003592863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moser C. Hypersexual disorder: just more muddled thinking. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2011;40(2):227–229. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9690-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Winters J. Hypersexual disorder: a more cautious approach. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2010;39(3):594–596. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9607-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reid RC, Garos S, Carpenter BN. Reliability, validity, and psychometric development of the Hypersexual Behavior Inventory in an outpatient sample of men. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity. 2011;18:30–51. [Google Scholar]

- 40.American Psychiatric Association. [Accessed December 12, 2012.];American Psychiatric Association board of trustees approves DSM-5 [press release] 2012 Dec; http://www.psych.org/File%20Library/Advocacy%20and%20Newsroom/Press%20Releases/2012%20Releases/12-43-DSM-5-BOT-Vote-News-Release--FINAL--3-.pdf.

- 41.American Psychiatric Association’s . DSM-5 Workgroup on Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders. [Accessed July 26, 2011.];Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory. 2010 http://www.dsm5.org/ProposedRevisions/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx?rid=415#.

- 42.Reid RC, Carpenter BN, Hook JN, et al. Report of findings in a DSM-5 field trial for hypersexual disorder. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2012;9(11):2868–2877. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parsons JT, Kelly BC, Bimbi DS, DiMaria L, Wainberg ML, Morgenstern J. Explanations for the origins of sexual compulsivity among gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sex Behavior. 2008;37(5):817–826. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walters GD, Knight RA, Lågström N. Is hypersexuality dimensional? Evidence for the DSM-5 from general population and clinical samples. Archives of Sex Behavior. 2011;40:1309–1321. doi: 10.1007/s10508-010-9719-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Embretson SE, Reise SP. Item Response Theory for Psychologists. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reeve BB, Fayers P. Applying item response theory modeling for evaluating questionnaire item and scale properties. In: Fayers P, Hays RD, editors. Assessing Quality of Life in Clinical Trials. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reise SP, Haviland MG. Item response theory and the measurement of clinical change. Journal of personality assessment. 2005;84(3):228–238. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8403_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parsons JT, Kelly BC, Bimbi DS, DiMaria L, Wainberg ML, Morgenstern J. Explanations for the origins of sexual compulsivity among gay and bisexual men. Arch Sex Beh. 2008;37(5):817–826. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9218-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stall R, Mills TC, Williamson J, Hart T, Greenwood G, Paul J, et al. Association of co-occurring psychosocial health problems and increased vulnerability to HIV/AIDS among urban men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(6):939–942. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.6.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stall R, Paul JP, Greenwood G, et al. Alcohol use, drug use and alcohol-related problems among men who have sex with men: the Urban Men’s Health Study. Addiction Nov. 2001;96(11):1589–1601. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.961115896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amtmann D, Bamer AM, Cook KF, Askew RL, Noonan VK, Brockway JA. University of Washington self-efficacy scale: A new self-efficacy scale for people with disabilities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, et al. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain. 2010;150(1):173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bentler PM. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological bulletin. 1990;107(2):238. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 56.West SG, Finch JF, Curran PJ. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reeve BB, Hays RD, Bjorner JB, et al. Psychometric evaluation and calibration of health-related quality of life item banks: plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Medical care. 2007;45(5):S22. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000250483.85507.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Samejima F. Estimation of latent ability using a response pattern of graded scores. Psychometrika Monograph Supplement. 1969 [Google Scholar]

- 59.IRTPRO [computer program]. Version 2.1. Skokie, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc; [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen WH, Thissen D. Local dependence indexes for item pairs using item response theory. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1997;22(3):265–289. [Google Scholar]