Abstract

Congenital heart diseases are one of the most common human birth defects. Though some congenital heart defects can be surgically corrected, treatment options for other congenital heart diseases are very limited. In many congenital heart diseases, genetic defects lead to impaired embryonic heart development or growth. One of the key development processes in cardiac development is chamber maturation, and alterations in this maturation process can manifest as a variety of congenital defects including noncompaction, systolic dysfunction, diastolic dysfunction, and arrhythmia. During development, to meet the increasing metabolic demands of the developing embryo, the myocardial wall undergoes extensive remodeling characterized by the formation of muscular luminal protrusions called cardiac trabeculae, increased cardiomyocyte mass, and development of the ventricular conduction system. Though the basic morphological and cytological changes involved in early heart development are clear, much remains unknown about the complex biomolecular mechanisms governing chamber maturation. In this review, we highlight evidence suggesting that a wide variety of basic signaling pathways and biomechanical forces are involved in cardiac wall maturation.

Keywords: Cardiac chamber maturation, Cardiac trabeculation, Conduction, Cardiomyocyte Proliferation, Left Ventricular Non-Compaction (LVNC), Neuregulin, Notch, Ephrin, BMP, Semaphorin, FGF, Retinoic Acid, Endothelin, Extracellular Matrix Signaling

Introduction

Cardiovascular malformation is one of the leading causes of human birth defects [Parker et al., 2010], and cardiovascular diseases are the number one cause of adult morbidity and mortality in the developed world [Go et al., 2013]. During development, in order to increase cardiac output, the vertebrate embryonic heart undergoes a series of complex morphogenic processes known collectively as cardiac chamber maturation. Alterations in these processes are linked to many cardiac diseases such as noncompaction cardiomyopathy (also known as hypertrabeculation), diastolic dysfunction, and arrhythmias [Teekakirikul et al., 2013] Monogenic alterations that lead to human congenital heart defects have been valuable in identifying key regulators of heart development [Teekakirikul et al., 2013]. Yet, these rare mutations do not explain the heterogeneity in cardiovascular defects observed clinically in both children and adults. Clearly, genetic mutations that completely impair heart development do not appear clinically. Advancements in our understanding of the mechanisms that govern cardiac chamber maturation and patient-specific genetic information are necessary for developing improved and personalized therapeutics for these congenital defects. In this review, we present evidence that collectively suggest a wide range of signaling pathways are involved in orchestrating cardiac chamber maturation.

Left Ventricular Non-Compaction

One of the most widely recognized disorders of cardiac maturation is left ventricular non-compaction (LVNC) [Jenni et al., 2007]. LVNC is characterized by prominent trabeculae and large recesses/sinuses between trabeculae, [Jenni et al., 2001, Stöllberger and Finsterer, 2004]. Patients with LVNC may be symptomatic or asymptomatic, and LVNC leads to heart failure, thromboembolic events, arrhythmias and/or sudden cardiac death [Bhatia et al., 2011, Paterick and Tajik, 2012, Ichida et al., 1999]. LVNC can occur as an isolated disease (called isolated left ventricular noncompaction or ILVNC) or in conjunction with other congenital defects [Peters 2012, and Stanton, 2009], suggesting multiple etiologies for LVNC. Due in large part to variable diagnostic criteria [Paterick and Tajik, 2012, Thavendiranathan et al., 2012], the true burden of LVNC is unknown, but is estimated to be 0.014%–1.3% of children referred to echocardiography laboratories [Oechslin et al., 2000].

The morphology of LVNC hearts closely resembles early embryonic hearts. Because of this resemblance, frequent comorbidity with other congenital cardiac malformations, and prevalence in infants, LVNC is widely considered to be caused by the embryonic arrest of cardiac wall maturation [Angelini et al., 1999, Chin et al., 1990, Sedmera and Thompson, 2000]. However, this hypothesis has been challenged recently [Ichida et al., 1999] given the identification of LVNC in adults [Oechslin et al., 2000, Murphy 2005, Stöllberger and Finsterer, 2004] and observation that some of the morphological features of LVNC are distinct from the embryonic heart [Wessels and Sedmera, 2003, Stanton et al., 2009]. Nevertheless, whether LVNC is strictly congenital, acquired, or both, there is a clear genetic component to LVNC [Teekakirikul et al., 2013, Oechlin and Jenni, 2011]. Indeed, the American Heart Association classifies LVNC as a genetic cardiomyopathy [Maron et al., 2006]. LVNC is associated with mutations in sarcomere-encoding genes, calcium handling genes, genes that encode proteins of the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex (DTNA), nuclear lamina, Nkx2.5 and with mutations that cause compromised mitochondrial function [reviewed in Teekakirikul et al., 2013]. Although the genetic studies of LVNC and other trabecular disorders have identified some genes associated with LVNC, we know little about how mutations in these genes lead to altered cardiac morphogenesis.

Basic Research in Cardiac Chamber Maturation Biology

Over the past 2 decades, though we have seen substantial progress in our understanding of the formation of the cardiovascular system, improvements in this understanding are necessary to develop therapies for non-compaction/trabecular diseases. Much of our understanding of cardiac ontology is derived from study of human, mouse, and chicken embryos. However, direct observation of heart development is limited in these organisms. The zebrafish (Dano rerio) has recently emerged as a powerful vertebrate model organism for studying early heart development [Beis and Stainier, 2006, Liu and Stainier, 2012]. The zebrafish heart is simpler than that of higher vertebrates, but recapitulates early cardiac development. Moreover, accumulating evidence suggests that genes responsible for essential steps of cardiovascular development and morphogenesis are conserved throughout vertebrates [Moorman and Christoffels, 2003]. Unlike the mouse or chicken, the zebrafish embryo develops entirely externally, and the transparency of the embryos enables direct, noninvasive observation of heart development at a cellular resolution. External development also makes it highly accessible for forward genetic approaches and for screening drug targets. Zebrafish embryos are particularly useful for studying developmental cardiac defects because they do not initially require a functioning cardiovascular system. Since their early oxygen needs can be met by passive diffusion, phenotypes that are lethal in other model systems can be studied in greater detail in zebrafish. In addition, technologies for creating zebrafish knockout, transgenic, and reporter lines are readily available.

EMBRYONIC CARDIAC CHAMBER MATURATION

During development, in order to increase cardiac output, the vertebrate embryonic heart undergoes a series of complex morphogenic changes known collectively as cardiac chamber maturation. The early embryonic heart is a smooth, two-layered linear heart tube composed of a luminal endocardial endothelial layer and an immature myocardial layer (Fig 1A). This tube later undergoes extensive growth and topological remodeling to generate the mature vertebrate heart. Though the ultimate cardiac wall topology is somewhat different between cardiac chambers and between species, the patterning and processes of wall maturation is well conserved [Sedmera et al., 2000]. Alterations in these processes are linked to many cardiac diseases such as non-compaction cardiomyopathy, diastolic dysfunction, and arrhythmias. A basic understanding of these processes is necessary to appreciate the morphological defects observed in non-compaction and trabecular disease and to identify how mutations in genes regulating these processes can lead to non-compaction phenotypes.

Figure 1. Cardiac chamber maturation.

Figure 1A–D features a schematized cross-section of a theoretical ventricle wall with the developing atrio-ventricular canal represented as the open break in the ventricle wall, such that the outer curvature is on the left and the inner curvature is on the right. (A) Early in development, the cardiac chamber wall is smooth and consists of endocardial cells and myocardial cells. (B) Emergence: Myocardial protrusions called trabeculae begin to appear in the outer curvature of the ventricle, projecting into to the lumen. The trabeculae are lined by a continuous layer of endocardium. (C) Trabeculation: Trabeculae increase in length and the chamber wall becomes topologically more complex as additional trabeculae form throughout the outer curvature, creating a meshwork network of interconnected trabeculae. The compact myocardium does not thicken appreciably. A third layer of cells, the epicardium, surrounds the developing heart. (D) Compaction/Remodeling. Trabeculae cease luminal growth, thicken radially, and their base coalesces to form part of the solid myocardial wall. The compact myocardium increases in mass concomitant with the coronary vessel formation in the myocardial wall. The compact myocardium is shown in dark blue, trabecular cardiomyocytes in cerulean, endocardial cells in green, and epicardial cells in purple. The developing cardiac vasculature is represented by gray circles outlined in green.

Cardiac chamber maturation can be separated into three interrelated processes—formation of myocardial projections called trabeculae, establishment of the conduction system, and thickening of the compact myocardium. Each of these processes has been well described historically, and our description reflects the published current views of leaders in the field. In the following sections, we will briefly describe the anatomical changes in the cardiac chamber associated these processes. In the sections following these descriptions, we will then discuss known regulators of chamber maturation and propose future directions for research in chamber maturation.

Trabeculation

We direct interested readers to the reviews by and references in Sedmera et al., [2000] and Moorman and Christoffels [2003] for in depth presentation of the morphological changes associated with trabeculation. Cardiac trabeculation begins after the cardiac looping stage to form a network of luminal projections called trabeculae which consist of myocardial cells covered by the endocardial layer. Trabeculae increase cardiac output and permit nutrition and oxygen uptake in the embryonic myocardium prior to coronary vascularization without increasing heart size [Liu et al., 2010, Minot, 1901, Rychter and Ostadal,1971]. As the cardiac wall matures, the trabeculae undergo extensive remodeling concomitant with compact myocardial proliferation, formation of the coronary vasculature and maturation of the conduction system. In humans, infants born with either hypotrabeculated or hypertrabeculated ventricles have impaired function [Weiford et al., 2004 and Breckenridge et al., 2007]. The anatomical changes associated with trabeculation can be divided into three distinct steps—emergence, trabeculation, and remodeling.

Emergence

In the human at Carnegie stage 12, chicken at stage 16/16, mouse at E9.5 and zebrafish around 60 hpf (hour post fertilization), myocardial protrusions begin to appear extending into the lumen [Sedmara et al., 2000, Moorman and Christoffels, 2003, Peshkovsky et al., 2011] (Figure 1B). Recent work using zebrafish embryos have described this process in greater detail [Peshkovsky et al., 2011]. Trabeculae begin to develop in the outer curvature of the ventricle in a stereotypical manner starting on the outer curvature ventrally across from the AV nodes. It is not clear whether these protrusions form by buckling of the myocardial wall, active invagination of cardiomyocytes into the lumen, active evagination of the endocardium into the myocardial layer, or some combination of these actions [Icardo and Fernandez-Teran, 1987, Marchionni 1995, Sedmera and Thomas, 1996] though Peshkovsky et al.’s work would suggest active invagination of the myocardium as the primary mechanism. In support of this idea, Liu et al. demonstrated that cardiac trabeculation is primarily driven by delamination of the cardiomyocytes from the compact myocardium [Liu et al., 2010].

Trabeculation

After the initial trabecular ridges form, trabecular projections propagate radially to form a network of trabeculae and also increase in length [Peshkovsky et al., 2011; Sedmera et al, 2000]. During this stage, the majority of the myocyte mass is contained within trabeculae rather than within the compact wall (Fig 1C). Cells along the longitudinal axis of each trabecula are more differentiated at the luminal side and less differentiated at the mural side [Sedmera and Thompson, 2011]. Defects at this stage manifest as either over or under trabeculated myocardial walls populated by thin trabeculae, and this stage is considered complete when the first signs of trabecular remodeling begin.

Remodeling

The final stage of trabecular growth is a period of remodeling also known as consolidation or compaction (independent of expansion of the compact myocardial layer discussed below). Species and cardiac chamber-specific differences in adult trabecular morphology are generally attributed to differences in remodeling. This stage is characterized by trabeculae ceasing growth in the luminal direction and thickening radially (Fig 1D). The bases of the trabeculae thicken and/or collapse to the point that they are indistinguishable from the myocardial wall proper. As the trabeculae compact, the spaces between trabeculae are transformed into capillaries. This compaction stage is considered complete when a “mature” trabeculated network is evident at Carnegie stage 22, chicken stage 34, and mouse at E14.5 [Sedmera et al., 2000]. Defects at this stage manifest as overly long, thin trabecular projections that are separated by deep invaginations in the wall.

Compact Myocardium Proliferation

Though consolidation and compaction of trabeculae increases myocytes mass, the compact myocardium ultimately provides most of the myocardial mass in the mature heart (Fig 1D). We direct interested readers to the reviews by and references in Risebro and Riley [2006] and Sedmera and Thompson [2011] for review of compact layer cardiomyocyte proliferation and related formation of coronary circulation. Initially, the linear heart tube is comprised of the endocardial and myocardial layers. Around the same time as the initiation of trabeculation, cells of the proepicardial organ migrate to the post-looped heart to form its outermost layer, the epicardium (Fig 1C). As the endocardium and part of the myocardium generate trabeculae, the more distal portion of the myocardial layer proliferates slowly. Interestingly, it is well accepted that these cells are less differentiated than the trabecular myocardium, and by that reasoning should have a greater proliferative capacity than the trabecular myocytes. Temporally, around the remodeling/compaction step of trabeculation (above), the epicardium invades the myocardial wall, forming the coronary vasculature and contributing cardiac fibroblasts to the myocardial wall. The appearance of coronary vasculature is accompanied by rapid proliferation of the compact layer.

As the compact layer grows in size and complexity, it supplants trabeculae myocardium as the major contractile force [Wessels and Sedmera, 2003]. This proliferation is concomitant with trabecular remodeling, so it is often difficult to distinguish whether altered myocardial wall structure is from maladaptive trabecular compaction or compact myocardium proliferation. Factors modulating the spatial and temporal growth of the compact layer are reviewed in Sedmera and Thompson [2011] and include FGFs, Wnts, RA, and erythropoietin [Merki et al., 2005, Pennisi 2003, Chen et al., 2002, and Stuckmann et al., 2003]. Further growth and rearrangement of the compact myocardium occur in post-natal development.

Conduction System

Non-compaction and trabecular diseases are often associated with arrhythmias, suggesting a role for altered cardiac action potential conduction in these disorders [Ichida et al., 1999]. Morphological development of the cardiac conduction system and the gene networks involved have been recently reviewed by Munshi et al [2012], Miquerol et al. [2011], and Christoffels and Moorman [2009]. In the normal adult vertebrate heart, the cardiac action potential (AP) is initiated in the atrial sinoatrial node then spreads through the atria, inducing atrial contraction. The AP is delayed in the atrioventriclar node which allows for completion of atrial contraction before initiation of ventricular contraction. The AP then travels through the atrioventriclar bundle and bundle branches and ultimately terminates in the Purkinje fibers of the arborized peripheral ventricular conduction system (PVCS). The PVCS, also called the His-Purkinje network, is responsible for depolarizing ventricular cardiomyocytes in a rapid, coordinated fashion. Clearly, the proper development of the cardiac conduction system is very complex and involves coordinated growth and differentiation processes. Due to its physical proximity within the cardiac wall and early embryonic function, the Purkinje fiber network/PVSC is directly impacted by altered wall maturation observed in noncompaction and trabecular diseases. Thus, we will restrict our discussion of the conduction system to the anatomical development of the Purkinje fiber network (PFN) in this section and the signaling networks involved in a later section.

The mature PVCS consist of Purkinje fibers (PFs) of myogenic origin, insulating fibers, and nervous input and is located within trabeculae in the subendocardial space between the endocardial cells and underlying differentiated cardiomyocytes. PFs do not require the insulating fibers and or external innervation as they can propagate the cardiac AP when trabeculae have just been formed [Christoffs and Moorman, 2009]. The morphological appearance of the PFs varies somewhat across vertebrates, but are generally characterized by underdeveloped sarcomeres, sarcoplasmic reticulum, and mitochondrial network; insulation by connective tissue (mature fibers only); and connected as an electrically excitable network detectable by retrograde tracing [reviewed in Munshi, 2012]. Based on lineage tracing data using different markers in different species, conduction cells are derived from cardiac progenitor cells and not from endocardial or epicardial cells [reviewed in Miquerol et al., 2011]. There is some debate as to whether conduction cells arise from direct progenitor differentiation into conduction cells, from cardiomyocyte differentiation into conduction cells, or if both derivations are possible [reviewed in Munshi, 2012]. Christoffels and Moorman [2009] have suggested a model of PF development in which differentiation of cardiomyocytes on the epicardial side of trabeculae into working cardiomyocytes is opposed by differentiation of cardiomyocytes on the endocardial side into working PF cells.

SIGNALING PATHWAYS IN CARDIAC CHAMBER MATURATION

Vertebrate small animal models including mouse, chicken and zebrafish have been used to study the basic cell signaling involved in cardiac wall maturation. Much of what we do know is from reverse genetic loss of function approaches in which removal of a gene results in a cardiac chamber maturation phenotype. While gene networks governing general cell survival and proliferation are essential for cardiac development, at the molecular level, cardiac maturation requires specific signaling networks including Notch, Neuregulin, Ephrin, BMP, FGF, Semaphorin, Retinoic acid, Endothelin, and extracellular matrix signaling (ECM). As of yet, no comprehensive model has emerged describing the specific molecular regulators of chamber maturation. In the following section, we will review the evidence implicating each of these pathways in wall maturation.

Notch

The Notch signaling pathway plays multiple roles during vertebrate cardiac differentiation and development, including regulation of valve formation, outflow tract development and cardiac chamber maturation. Upon binding of DELTA or JAGGED family ligands, the extracellular portion of NOTCH is cleaved by ADAM17 (ADAM metallopetidase domain 17) and the intracellular portion is cleaved by a γ-secretase. This releases the NOTCH intracellular domain (NICD) into the cytoplasm there it translocates into the nucleus and associates with transcription factors to activate downstream target genes [MacGrogan et al., 2010] (Fig 2A). Notch activation is upstream of Ephrin and Neuregulin-based modulation of trabeculation and BMP10 modulation of cardiomyocyte proliferation (Fig 2A).

Figure 2. Signaling pathways in cardiac chamber maturation.

Several signaling pathways have been identified as key regulators of cardiac chamber morphogenesis. Please see below for abbreviations. (A) Canonical NOTCH ligands including Delta and Jagged family members bind to NOTCH family receptors. Upon binding, ADAM17 cleaves the extracellular domain of NOTCH and γ-secretase cleaves the intracellular domain of NOTCH, releasing the NICD into the cytoplasm. NICD translocates into the nucleus and modulates gene transcription. NOTCH activation leads to stimulation of EphrinB2 signaling through EPH4 and NRG1 signaling through ERBB2/4, both of which are essential for trabeculation. NOTCH activation also leads to activation of BMP signaling through BMP10/BMPR interactions and FGF signaling through FGFR. BMP and FGF signaling are essential for cardiomyocyte proliferation and expansion of the compact myocardium. (B) Other signaling pathways essential for cardiac chamber maturation. SEMA6D signaling though PLXNA1 activates the enabled homolog MENA, modulating both trabeculation and compact myocardium proliferation/expansion. Vitamin A is oxidized into retinoic acid. Retinoic acid family members, RXRs, bind retinoic acid and translocate into the nucleus where they influence gene transcription involved in compact cardiomyocyte proliferation. Pro-endothelin secreted into extracellular space is converted into ET-1 by ECE1. ET-1 binding activates the G-protein coupled receptor EDNRA, leading to downstream signaling and gene transcription essential for Purkinje Fiber formation. Diverse extracellular matrix molecules collectively referred to as ECM, either whole or after proteolysis by MMPs, interact with α/β integrin heterodimers. This induces conformation changes in the integrin heterodimer that activate downstream signal transduction that ultimately modulates all elements cardiac chamber maturation. Abbreviations: NRG1; Neuregulin-1: ERBB2/4; heterodimer with ErbB2 (v-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 2) and ErbB4 (v-erb-a erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 4): EFNB2; Ephrin-B2: EPHB4; EPH receptor B4: ADAM17; ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17: NOTCH; NOTCH family receptors: γ-secretase; gamma-secretase: NICD; NOTCH intracellular domain: BMP10; Bone Morphogenic Protein 10: BMPR2; Bone morphogenic Protein receptor, type II: SMAD; SMAD family transcription factors: FGF; Fibroblast Growth Factors: FGFR; Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptors: SEMA6D; Semaphorin 6D: PLXNA1; Plexin A1: MENA; Enabled homolog (mammalian): RXR; Retinoic Acid Receptor family: Pro-ET; Pro-endothelin: ECE1; Endothelin-converting enzyme 1: ET-1; Endothelin 1: EDNRA; Endothelin receptor type A: ECM; Extra Cellular Matrix components: MMP; Matrix Metalloprotease.

Consistent with the involvement of Notch signaling in multiple aspects of cardiac development, components of the Notch pathway show dynamic spatial and temporal expression patterns in the developing vertebrate heart and both endocardial and myocardial expression have been described [reviewed by MacGrogan et al., 2010]. The endocardium expresses DELTA4, NOTCH1, and NOTCH4 [Krebs et al., 2000, Del Amo et al., 1992, Uyttendaele et al., 1996] while the myocardium expresses JAGGED1 and NOTCH2 [Loomes 1999, McCright et al., 2002]. NOTCH1 is expressed in the endocardium and its activated form shows strongest expression at the base of the ventricular trabeculae. In addition, Notch1 or RBPjk (effector transcription factor) deficient mice display deficient cardiac wall maturation including failure of cardiac trabeculation, reduced marker genes expression, and decreased cardiomyocyte proliferation [Grego-Bessa et al., 2007]. The myocardially expressed NOTCH2 2 has also been shown to play a role in chamber maturation. NOTCH2 is down-regulated in the compact myocardium layer during mouse cardiac development. Overexpression of Notch2 in the myocardium leads to hypertrabeculation, reduced compaction, and septal defects [Yang et al., 2012]. Double knockout of Numb and Numblike (suppressors of NOTCH2) leads to a comparable phenotype as NOTCH2 overexpression and increases BMP10 expression which modulates trabeculation (discussed below) [Yang et al., 2012].

Neuregulin/ErbB

Neuregulin-1 (NRG1) is a Type 1 transmembrane protein and a member of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) family of ligands. It is highly expressed in the cardiovascular system and has been implicated in heart development and disease [Odiete et al., 2012]. Transmembrane NRG1 acts as a paracrine ligand. In the heart, binding of NRG-1 to the ERBB family receptor ERBB4 promotes formation of ERBB4/ERBB2 heterodimeric signaling complex. ERBB2 tyrosine kinase activity phosphorylates the C-terminal domains, leading to downstream signaling modulation of gene expression through (Fig 2A)[Yarden and Sliwkowski, 2001].

In the heart, endocardial derived Neuregulin signaling through ERBB2/4 heterodimers in the myocardium is essential for proper chamber maturation [reviewed in Fuller et al., 2008]. Mice lacking NRG1 [Meyer 1995] or functional NRG1 Ig-like domain 1 [Kramer et al., 1996], die before birth due to defective cardiac trabeculation. Likewise, mice lacking either ERBB2 [Lee et al., 1995] or ErbB4 [Gassmann et al. 1995] also die in early gestation due to defective trabeculation. Similar to mice, zebrafish devoid of functional ERBB2 protein [Liu 2010] or with ERBB activity pharmacologically inhibited [Peshkovsky et al., 2011] do not form trabeculae [Liu et al., 2010]. Detailed lineage tracing and transplantation studies in zebrafish embryo has suggested that initiation of trabeculation is driven by directional migration of cardiomyocytes regulated by ERBB2 signaling [Liu et al., 2010].

Since NRG1, ERBB2, and ERBB4 deficiency results in embryonic lethality in multiple model organisms, it is unlikely that complete loss-of-function mutations are present in the human populace with congenital heart malformations. However, it is possible that partial loss of function in these genes or in the up or downstream mediators of Neureglin signaling could manifest within the cardiac wall malformation disease etiology.

EphrinB2/B4

Ephrin signaling is essential for normal endothelial cell function and thus heart development. In the heart, Ephrin-B2 (EFNB2) and one of its receptors, EPHB4, are expressed in the endothelial cells lining trabeculae [Wang et al., 1998]. Eph4 tyrosine kinase activity leads to downstream signaling that modulates cell shape, migration, and adhesion [Salvucci and Tosato, 2012] (Fig 2A). In mice, trabeculae fail to form in the absence of EFNB2 [Wang et al., 1998] or EPHB4 [Gerety et al., 1999].

BMP

Bone morphogenic protein-10 (BMP10) signaling plays an important role in modulating heart development [Lowery et al., 2010]. BMP10 expression is restricted to cardiomyocytes in the developing and post-natal heart [Neuhaus et al., 1999]. BMP10 is part of the TGF-β superfamily of ligands with specificity for ALK1, ALK6, and BMPR2 receptors. Ligand-receptor binding initiates SMAD signal transduction to modulate gene transcription [Lowery et al., 2010] (Fig 2A). Global deletion of BMP10 is embryonic lethal with severely reduced cardiomyocyte proliferative capacity [Chen et al., 2004]. BMP10 appears to modulate cardiomyocyte differentiation through activation of transcription factors Nkx2.5, Mef2c [Chen et al., 2004], and Tbx20 [Zhang et al., 2011].

FGF

Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family of secreted ligands binds to fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR) in either a cell autonomous or non-cell autonomous manner, leading to complex, cell and context-specific intracellular signaling (Fig 2A). Proliferation of the compact myocardium requires FGF signaling [Mikawa 1995, Mima et al., 1995]. In mouse embryos, the FGF9 family members FGF9, FGF16, and FGF20 are expressed in both the endocardium and epicardium and are important regulators of regulate cardiomyocyte proliferation [Lavine et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2008].

Semaphorins

Semaphorin signaling through Plexin receptors modulate cell behavior and gene transcription through complex intracellular signaling cascades [Zhou et al., 2008] (Fig 2B). Though Semaphorins are more typically known for their role in axonal migration, members of the semaphorin family, such as SEMA6D (Semaphorin-6D) have been shown to play a role cardiac patterning, and SEMA6D loss-of-function leads to trabeculation phenotypes [Toyofuku et al., 2004a, b]. In mouse and chicken embryos, knockdown of SEMA6D or its receptor PLXNA1 (PlexinA1) in mouse and chicken embryos leads to the typical noncompaction phenotype with a thin compact myocardium and expansive spongy trabeculated myocardium [Toyofuku et al., 2004a, b].

Retinoic Acid

Retinoic acid (RA) is derived from Vitamin A. Both Vitamin A deficiency [Wilson and Warkany, 1949; Wilson et al., 1953] and exposure of embryos to excess Vitamin A leads to cardiac defects [Morriss-Kay, 1992]. Canonically, lipophilic RA diffuses into cells and binds to the retinoic acid receptor RXRs on the nuclear membrane (Fig 2B). RXRs directly bind DNA to regulate gene transcription [Duester, 2008]. Genetic ablation of the retinoic acid receptor RXRα is embryonic lethal in mice due to failed proliferation of the compact myocardium [Sucov et al., 1994]. This arrest of cardiomyocyte proliferation is not directly attributable to RA signaling on cardiomyocytes. Rather, RA appears to induce the epicardium to secrete trophic factor(s) that mediate cardiomyocyte proliferation [Chen et al., 2002, Stuckmann et al., 2003].

Endothelin

In the developing heart, cardiomyocyte differentiation into Purkinje fibers is regulated in part by endothelin signaling [Takebayashi-Suzuki, 2000]. Pro-endothelin (Pro-ET), the precursor of active endothelin-1 (ET1), is produced by endothelial cells in response to shear stress (the force of fluid flow parallel to the endocardial surface). Presumably due to higher levels of shear stress, in the heart endocardial and arterial endothelial cells, but not venous endothelial cells or cardiomyocytes, produce the endothelin-converting enzyme-1 (ECE1) necessary to convert Pro-ET into ET1. ET1 interacts with the G-protein coupled receptor EDNRA (endothelin receptor type A) to induce cardiomyocytes to differentiate into Purkinje fibers [Gourdie et al., 1998, Takebayashi-Suzuki, 2000] (Fig 2B). ECE1 is required for normal Purkinje fiber formation [Hall et al., 2004].

Extracellular Matrix Molecule Signaling

Each of the cardiac layers—endocardial, myocardial, and epicardial—are separated by layers of extracellular matrix (ECM). ECM-cell interactions are coupled cell signaling though transmembrane proteins called integrins which, upon binding undergon conformational changes that lead to complex cell and context-depending cell signaling (Fig 2B). Integrins modulate intracellular signaling cascades to modulate many cellular processes including growth, migration, survival, and differentiation. Integrins exist as heterodimers, and ligand specificity is conferred by different combinations α and β subunit isoforms. The α4 integrin is essential for cell adhesion during cardiac development [Yang et al., 1995]. The exact composition of cardiac ECM is important for normal cardiac development. Though there are many ECM proteins present in the developing heart, collagen [Tahkola et al., 2008], versician [Cooley et al., 2012] and nephronectin [Patra et al., 2011] have emerged as important ECM components. During cardiac morphogenesis, the ECM is broken down by matrix metalloproteases to facilitate cell migration. ECM composition is regulated at least in part by the matrix metalloprotease ADAMTS1, which is necessary for trabeculation [Stankunas et al., 2008].

BIOMECHANICAL FORCES IN CARDIAC WALL MATURATION

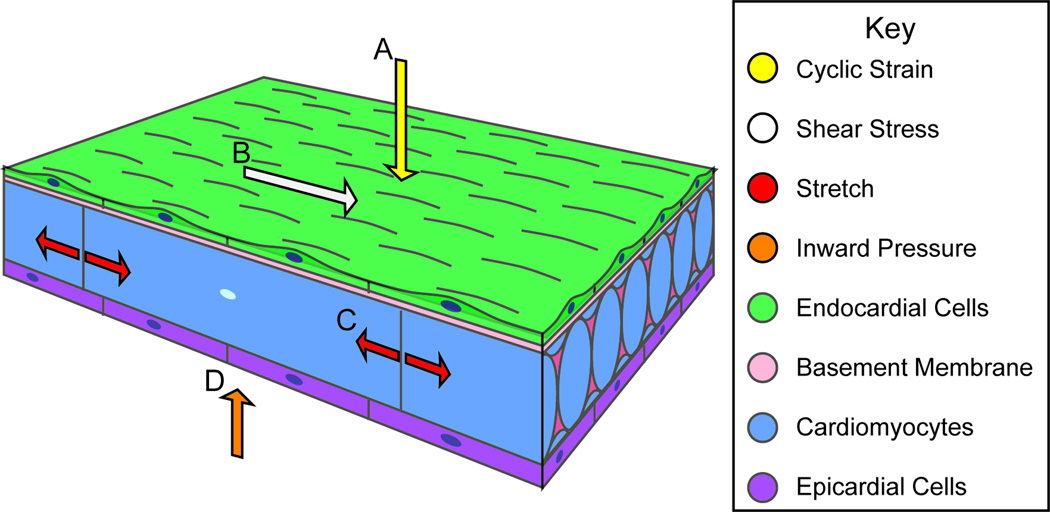

Though genes regulating cell signaling are clearly essential for cardiac chamber maturation, epigenetic factors such as the biomechanical forces influence heart development. We direct interested readers to a recent review by Granados-Riveron and Brook [2012] for an analysis of mechanical forces in heart development [Granados-Riveron and Brook, 2012]. During development, the heart is exposed to many biomechanical forces including those exerted on the wall by blood flow (shear stress), by fluid pressure (cyclic strain), within the wall by cell-cell attachments, and on the wall by extracardiac pressures (Fig 3). In general, the signaling mechanisms through which cells translate biomechanical forces into changes in the signaling events that modulate cardiac wall patterning are poorly understood.

Figure 3. Biomechanical forces in Cardiac Wall Maturation.

Biomechanical forces are important for normal developmental patterning. Forces exerted on the wall from blood flow include (A) cyclic strain, a force perpendicular to the vessel wall, and (B) shear stress, the frictional force parallel to the vessel wall. (C) Force from cardiac contraction exerts strain on myocardial and endothelial cell-cell junctions. (D) The splachnopleural membrane interacts with the myocardial wall during development and may exert an inward pressure on the myocardial wall.

Flow

Fluid flow plays an important role in trabeculation, cardiomyocyte proliferation, and establishment of the cardiac conduction system. While flow exerts a force parallel to the vessel wall called shear stress, fluid pressure exerts force on the developing heart to the vessel wall. This pressure, also known as mechanical load, can be manipulated ex vivo in developing hearts. Reduced mechanical load is mimicked by maintaining hearts in normal atmospheric pressure, while increased mechanical load is mimicked by filling the ventricles to end diastolic volume by injection of silicon oils. In chick, changing the mechanical load leads to altered development of the conduction system, impaired growth, and disorganized trabeculae [Sankova et al., 2010].

Likewise, zebrafish carrying an atrial sarcomere mutation, the Wea mutant, have weak blood flow in the ventricles [Berdougo et al., 2003]. Wea mutants exhibit reduced trabeculation [Peshkovsky et al., 2011>]. One way that cells sense flow is through the bending of primary cilia. Primary cilia are sensory organelles that protrude from the normal plane of the cell membrane and are found on nearly every cell type, including endothelial cells. Interestingly, mice that do not have primary cilia have decreased cardiac trabeculation and abnormal outflow tract development [Clement et al., 2009], suggesting a role for shear stress sensing in chamber maturation.

Stretch

During the cardiac cycle, individual cardiomyocytes are subjected to stretch. When stretched, endothelial cells produce Pro-ET which is converted by ECE1 into ET1, and ET1 signaling is essential for Purkinje fiber differentiation [Takebayash-Suzuki, 2000] Pharmacological inhibition of stretch responsive channels leads to decreased expression of ECE1 in the endocardium and decreased expression of the Purkinje fiber specific marker connexin40 in the developing chick ventricle [Hall et al., 2004]. Conversely, pressure overload by truncal banding increases Purkinje fiber formation [Hall et al., 2004]. Thus, mechanical forces play a role in Purkinje fiber development at least in part through modulation of ET1 signaling.

Inward forces

The developing heart in its entirety is contained within the splanchnopleural cavity. Advances in four-dimensional optical coherence tomography (OCT) have permitted study of the complex interrelationship between cardiac layers during the cardiac cycle. Garita et al. [2009] used OCT imaging in chick and mouse embryos to demonstrate that the splanchnopleural membrane interacts with the myocardial wall. This study is the first to demonstrate a direction interaction of the developing heart interacts with its boundaries, suggesting that inward transduction of this mechanical interaction could play a role in final positioning of the heart.

NEW AREAS FOR INVESTIGATION

Though a few genes have been implicated as necessary for trabeculation, much work remains to fully characterize cardiac trabeculation. Greater understanding of the normal morphogenesis of the heart will inform treatment efforts and could play a role in developing personalized therapeutics.

The first question which remains to be addressed is how the spatial pattern of cardiac trabeculation is generated. NRG-1 and its receptors appear to be expressed uniformly in the ventricular endocardium and myocardium respectively; however, it is not clear whether Neuregulin/ErbB signaling is spatially activated to select certain cardiomyocytes to initiate cardiac trabeculation. Alternatively the spatial regulation of cardiac trabecular initiation can be achieved by the interplay of multiple signaling pathways, such as the Neuregulin/ErbB and Semaphorin/Plexin pathways. In addition, the initiation of cardiac trabeculation appears to be driven by cardiomyocytes delamination, but little is known about the cellular basis of cardiomyocyte delamination. It is also conceivable that once certain cardiomyocytes are selected to initiate cardiac trabeculation, they might inhibit their neighbors from adopting a trabecular cardiomyocyte fate. It will be interesting to determine whether and how such lateral inhibition mechanism is employed to maintain the homeostasis of the compact myocardium. Mechanical force also plays an important role in trabeculation. Cardiac trabeculation is significantly reduced in zebrafish wea mutant embryos with reduced blood flow in the ventricle. Likewise, in human, mutations in sarcomere –encoding genes can cause trabecular non-compaction in the left ventricles, suggesting in humans mechanical force associated with cardiac contraction can also have an effect on embryonic heart development as well. Thus, it will be important to study how the heart senses and responds to mechanical force to regulate cardiac chamber maturation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by an NIH R00 award (HL109079) and a startup package from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill to J.L. We thank Didier Stainier for critical reading of this manuscript.

Biographies

Jiandong Liu is an assistant professor at the University of North Carolina, Chapel hill. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor and he performed his postdoctoral training at University of California, San Francisco. His laboratory is using zebrafish as a model system to study cardiac development and function.

Leigh Ann Samsa is a graduate student at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. She completed her B.S. degree in Biology at Duke University. Her graduate research is focused on understanding genetic and epigenetic regulation of cardiac development.

Besty Yang is an undergraduate student majoring in biology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- Angelini A, Melacini P, Barbero F, Thiene G. Evolutionary persistence of spongy myocardium in humans. Circulation. 1999;99:2475–2475. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.18.2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beis D, Stainier DYR. In vivo cell biology: Following the zebrafish trend. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;16:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdougo E, Coleman H, Lee DH, Stainier DYR, Yelon D. Mutation of weak atrium/atrial myosin heavy chain disrupts atrial function and influences ventricular morphogenesis in zebrafish. Development. 2003;130:6121–6129. doi: 10.1242/dev.00838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia NL, Tajik AJ, Wilansky S, Steidley DE, Mookadam F. Isolated noncompaction of the left ventricular myocardium in adults: A systematic overview. J Card Fail. 2011;17:771–778. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckenridge RA, Anderson RH, Elliott PM. Isolated left ventricular non-compaction: The case for abnormal myocardial development. Cardiol Young. 2007;17:124–129. doi: 10.1017/S1047951107000273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckenridge RA, Anderson RH, Elliott PM. Isolated left ventricular non-compaction: The case for abnormal myocardial development. Cardiol Young. 2007;17:124–129. doi: 10.1017/S1047951107000273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Shi S, Acosta L, Li W, Lu J, Bao S, Chen Z, Yang Z, Schneider MD, Chien KR, Conway SJ, Yoder MC, Haneline LS, Franco D, Shou W. BMP10 is essential for maintaining cardiac growth during murine cardiogenesis. Development. 2004;131:2219–2231. doi: 10.1242/dev.01094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen TH-, Chang T, Kang J, Choudhary B, Makita T, Tran CM, Burch JBE, Eid H, Sucov HM. Epicardial induction of fetal cardiomyocyte proliferation via a retinoic acid-inducible trophic factor. Dev Biol. 2002;250:198–207. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin TK, Perloff JK, Williams RG, Jue K, Mohrmann R. Isolated noncompaction of left ventricular myocardium. A study of eight cases. Circulation. 1990;82:507–513. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffels VM, Moorman AFM. Development of the cardiac conduction system: Why are some regions of the heart more arrhythmogenic than others? Circulation: Arrhythmia and Electrophysiology. 2009;2:195–207. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.829341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement CA, Kristensen SG, Mollgard K, Pazour GJ, Yoder BK, Larsen LA, Christensen ST. The primary cilium coordinates early cardiogenesis and hedgehog signaling in cardiomyocyte differentiation. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3070–3082. doi: 10.1242/jcs.049676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooley MA, Fresco VM, Dorlon ME, Twal WO, Lee NV, Barth JL, Kern CB, Iruela-Arispe ML, Argraves WS. Fibulin-1 is required during cardiac ventricular morphogenesis for versican cleavage, suppression of ErbB2 and Erk1/2 activation, and to attenuate trabecular cardiomyocyte proliferation. Dev Dyn. 2012;241:303–314. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.23716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Amo FF, Smith DE, Swiatek PJ, Gendron-Maguire M, Greenspan RJ, McMahon AP, Gridley T. Expression pattern of motch, a mouse homolog of drosophila notch, suggests an important role in early postimplantation mouse development. Development. 1992;115:737–744. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.3.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duester G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 2008;134:921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller SJ, Sivarajah K, Sugden PH. ErbB receptors, their ligands, and the consequences of their activation and inhibition in the myocardium. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:831–854. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.02.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garita B, Jenkins MW, Han M, Zhou C, Vanauker M, Rollins AM, Watanabe M, Fujimoto JG, Linask KK. Blood flow dynamics of one cardiac cycle and relationship to mechanotransduction and trabeculation during heart looping. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H879–H891. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00433.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann M, Casagranda F, Orioli D, Simon H, Lai C, Klein R, Lemke G. Aberrant neural and cardiac development in mice lacking the ErbB4 neuregulin receptor. Nature. 1995;378:390–394. doi: 10.1038/378390a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerety SS, Wang HU, Chen Z, Anderson DJ. Symmetrical mutant phenotypes of the receptor EphB4 and its specific transmembrane ligand ephrin-B2 in cardiovascular development. Mol Cell. 1999;4:403–414. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Magid D, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Schreiner PJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke Statistics—2013 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourdie RG, Wei Y, Kim D, Klatt SC, Mikawa T. Endothelin-induced conversion of embryonic heart muscle cells into impulse-conducting purkinje fibers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1998;95:6815–6818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granados-Riveron JT, Brook JD. The impact of mechanical forces in heart morphogenesis. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2012;5:132–142. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.961086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grego-Bessa J, Luna-Zurita L, del Monte G, Bolos V, Melgar P, Arandilla A, Garratt AN, Zang H, Mukouyama YS, Chen H, Shou W, Ballestar E, Esteller M, Rojas A, Perez-Pomares JM, de la Pompa JL. Notch signaling is essential for ventricular chamber development. Dev Cell. 2007;12:415–429. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall CE, Hurtado R, Hewett KW, Shulimovich M, Poma CP, Reckova M, Justus C, Pennisi DJ, Tobita K, Sedmera D, Gourdie RG, Mikawa T. Hemodynamic-dependent patterning of endothelin converting enzyme 1 expression and differentiation of impulse-conducting purkinje fibers in the embryonic heart. Development. 2004;131:581–592. doi: 10.1242/dev.00947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertig CM, Kubalak SW, Wang Y, Chien KR. Synergistic roles of neuregulin-1 and insulin-like growth factor-I in activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway and cardiac chamber morphogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37362–37369. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icardo JM, Fernandez-Teran A. Morphologic study of ventricular trabeculation in the embryonic chick heart. Acta Anat (Basel) 1987;130:264–274. doi: 10.1159/000146455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icardo JM, Fernandez-Teran A. Morphologic study of ventricular trabeculation in the embryonic chick heart. Acta Anat (Basel) 1987;130:264–274. doi: 10.1159/000146455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichida F, Hamamichi Y, Miyawaki T, Ono Y, Kamiya T, Akagi T, Hamada H, Hirose O, Isobe T, Yamada K, Kurotobi S, Mito H, Miyake T, Murakami Y, Nishi T, Shinohara M, Seguchi M, Tashiro S, Tomimatsu H. Clinical features of isolated noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium: Long-term clinical course, hemodynamic properties, and genetic background. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:233–240. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenni R, Oechslin EN, van der Loo B. Isolated ventricular non-compaction of the myocardium in adults. Heart. 2007;93:11–15. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.082271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenni R, Oechslin E, Schneider J, Jost CA, Kaufmann PA. Echocardiographic and pathoanatomical characteristics of isolated left ventricular non-compaction: A step towards classification as a distinct cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2001;86:666–671. doi: 10.1136/heart.86.6.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer R, Bucay N, Kane DJ, Martin LE, Tarpley JE, Theill LE. Neuregulins with an ig-like domain are essential for mouse myocardial and neuronal development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:4833–4838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.10.4833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs LT, Xue Y, Norton CR, Shutter JR, Maguire M, Sundberg JP, Gallahan D, Closson V, Kitajewski J, Callahan R, Smith GH, Stark KL, Gridley T. Notch signaling is essential for vascular morphogenesis in mice. Genes & Development. 2000;14:1343–1352. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavine KJ, Yu K, White AC, Zhang X, Smith C, Partanen J, Ornitz DM. Endocardial and epicardial derived FGF signals regulate myocardial proliferation and differentiation in vivo. Developmental Cell. 2005;8:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K, Simon H, Chen H, Bates B, Hung M, Hauser C. Requirement for neuregulin receptor erbB2 in neural and cardiac development. Nature. 1995;378:394–398. doi: 10.1038/378394a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Bressan M, Hassel D, Huisken J, Staudt D, Kikuchi K, Poss KD, Mikawa T, Stainier DY. A dual role for ErbB2 signaling in cardiac trabeculation. Development. 2010;137:3867–3875. doi: 10.1242/dev.053736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Stainier DYR. Zebrafish in the study of early cardiac development. Circulation Research. 2012;110:870–874. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.246504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loomes KM, Underkoffler LA, Morabito J, Gottlieb S, Piccoli DA, Spinner NB, Scott Baldwin H, Oakey RJ. The expression of Jagged1 in the developing mammalian heart correlates with cardiovascular disease in alagille syndrome. Human Molecular Genetics. 1999;8:2443–2449. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.13.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowery JW, de Caestecker MP. BMP signaling in vascular development and disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu SY, Sheikh F, Sheppard PC, Fresnoza A, Duckworth ML, Detillieux KA, Cattini PA. FGF-16 is required for embryonic heart development. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;373:270–274. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacGrogan D, Nus M, de la Pompa JL. Notch signaling in cardiac development and disease. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;92:333–365. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(10)92011-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron BJ, Towbin JA, Thiene G, Antzelevitch C, Corrado D, Arnett D, Moss AJ, Seidman CE, Young JB. Contemporary definitions and classification of the cardiomyopathies: An american heart association scientific statement from the council on clinical cardiology, heart failure and transplantation committee; quality of care and outcomes research and functional genomics and translational biology interdisciplinary working groups; and council on epidemiology and prevention. Circulation. 2006;113:1807–1816. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.174287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCright B, Lozier J, Gridley T. A mouse model of alagille syndrome: Notch2 as a genetic modifier of Jag1 haploinsufficiency. Development. 2002;129:1075–1082. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.4.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merki E, Zamora M, Raya A, Kawakami Y, Wang J, Zhang X, Burch J, Kubalak SW, Kaliman P, Belmonte JCI, Chien KR, Ruiz-Lozano P. Epicardial retinoid X receptor α is required for myocardial growth and coronary artery formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:18455–18460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504343102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D, Birchmeier C. Multiple essential functions of neuregulin in development. Nature. 1995;378:386–390. doi: 10.1038/378386a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mima T, Ueno H, Fischman DA, Williams LT, Mikawa T. Fibroblast growth factor receptor is required for in vivo cardiac myocyte proliferation at early embryonic stages of heart development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1995;92:467–471. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minot CS. On a hitherto unrecognised circulation without capillaries in the organs of Vertebrata. Proc Boston Soc Nat Hist. 1901;29:185–215. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miquerol L, Beyer S, Kelly RG. Establishment of the mouse ventricular conduction system. Cardiovascular Research. 2011;91:232–242. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman AFM, Christoffels VM. Cardiac chamber formation: Development, genes, and evolution. Physiological Reviews. 2003;83:1223–1267. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00006.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morriss-Kay G. Retinoic acid and development. Pathobiology. 1992;60:264–270. doi: 10.1159/000163733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munshi NV. Gene regulatory networks in cardiac conduction system development. Circulation Research. 2012;110:1525–1537. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.260026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus H, Rosen V, Thies RS. Heart specific expression of mouse BMP-10 a novel member of the TGF-beta superfamily. Mech Dev. 1999;80:181–184. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00221-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odiete O, Hill MF, Sawyer DB. Neuregulin in cardiovascular development and disease. Circ Res. 2012;111:1376–1385. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.267286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oechslin EN, Attenhofer Jost CH, Rojas JR, Kaufmann PA, Jenni R. Long-term follow-up of 34 adults with isolated left ventricular noncompaction: A distinct cardiomyopathy with poor prognosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36:493–500. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00755-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oechslin E, Jenni R. Left ventricular non-compaction revisited: A distinct phenotype with genetic heterogeneity? European Heart Journal. 2011;32:1446–1456. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker SE, Mai CT, Canfield MA, Rickard R, Wang Y, Meyer RE, Anderson P, Mason CA, Collins JS, Kirby RS, Correa A for the National Birth Defects Prevention Network. Updated national birth prevalence estimates for selected birth defects in the united states, 2004?2006. Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 2010;88:1008–1016. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterick TE, Tajik AJ. Left ventricular noncompaction: A diagnostically challenging cardiomyopathy. Circ J. 2012;76:1556–1562. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-12-0666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterick TE, Umland MM, Jan MF, Ammar KA, Kramer C, Khandheria BK, Seward JB, Tajik AJ. Left ventricular noncompaction: A 25-year odyssey. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2012;25:363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patra C, Diehl F, Ferrazzi F, van Amerongen MJ, Novoyatleva T, Schaefer L, Muhlfeld C, Jungblut B, Engel FB. Nephronectin regulates atrioventricular canal differentiation via Bmp4-Has2 signaling in zebrafish. Development. 2011;138:4499–4509. doi: 10.1242/dev.067454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peshkovsky C, Totong R, Yelon D. Dependence of cardiac trabeculation on neuregulin signaling and blood flow in zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:446–456. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Risebro CA, Riley PR. Formation of the ventricles. Scientificworldjournal. 2006;6:1862–1880. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rychter Z, Ostadal B. Fate of “sinusoidal” intertrabecular spaces of the cardiac wall after development of the coronary vascular bed in chick embryo. Folia Morphol. 1971;19:31–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvucci O, Tosato G. Advances in cancer research. Academic Press; Essential roles of EphB receptors and EphrinB ligands in endothelial cell function and angiogenesis; pp. 21–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankova B, Machalek J, Sedmera D. Effects of mechanical loading on early conduction system differentiation in the chick. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1571–H1576. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00721.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedmera D, Pexieder T, Vuillemin M, Thompson RP, Anderson RH. Developmental patterning of the myocardium. Anat Rec. 2000;258:319–337. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(20000401)258:4<319::AID-AR1>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedmera D, Thomas PS. Trabeculation in the embryonic heart. Bioessays. 1996;18:607–607. doi: 10.1002/bies.950180714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedmera D, Thompson RP. Myocyte proliferation in the developing heart. Developmental Dynamics. 2011;240:1322–1334. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankunas K, Hang CT, Tsun ZY, Chen H, Lee NV, Wu JI, Shang C, Bayle JH, Shou W, Iruela-Arispe ML, Chang CP. Endocardial Brg1 represses ADAMTS1 to maintain the microenvironment for myocardial morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2008;14:298–311. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton C, Bruce C, Connolly H, Brady P, Syed I, Hodge D, Asirvatham S, Friedman P. Isolated left ventricular noncompaction syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:1135–1138. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stöllberger C, Finsterer J. Left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2004;17:91–100. doi: 10.1016/S0894-7317(03)00514-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuckmann I, Evans S, Lassar AB. Erythropoietin and retinoic acid, secreted from the epicardium, are required for cardiac myocyte proliferation. Dev Biol. 2003;255:334–349. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucov HM, Dyson E, Gumeringer CL, Price J, Chien KR, Evans RM. RXR alpha mutant mice establish a genetic basis for vitamin A signaling in heart morphogenesis. Genes & Development. 1994;8:1007–1018. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahkola J, Rasanen J, Sund M, Makikallio K, Autio-Harmainen H, Pihlajaniemi T. Cardiac dysfunction in transgenic mouse fetuses overexpressing shortened type XIII collagen. Cell Tissue Res. 2008;333:61–69. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0617-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebayashi-Suzuki K, Yanagisawa M, Gourdie RG, Kanzawa N, Mikawa T. In vivo induction of cardiac purkinje fiber differentiation by coexpression of preproendothelin-1 and endothelin converting enzyme-1. Development. 2000;127:3523–3532. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.16.3523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teekakirikul P, Kelly MA, Rehm HL, Lakdawala NK, Funke BH. Inherited cardiomyopathies: Molecular genetics and clinical genetic testing in the postgenomic era. The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics. 2013;15:158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AThavendiranathan P, Dahiya A, Phelan D, Desai MY, Tang WHW. Isolated left ventricular non-compaction controversies in diagnostic criteria, adverse outcomes and management. Heart. 2012 doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-302816. Published Online First: 26 November 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyofuku T, Zhang H, Kumanogoh A, Takegahara N, Yabuki M, Harada K, Hori M, Kikutani H. Guidance of myocardial patterning in cardiac development by Sema6D reverse signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2004a;6:1204–1211. doi: 10.1038/ncb1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyofuku T, Zhang H, Kumanogoh A, Takegahara N, Suto F, Kamei J, Aoki K, Yabuki M, Hori M, Fujisawa H, Kikutani H. Dual roles of Sema6D in cardiac morphogenesis through region-specific association of its receptor, Plexin-A1, with off-track and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor type 2. Genes Dev. 2004b;18:435–447. doi: 10.1101/gad.1167304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyttendaele H, Marazzi G, Wu G, Yan Q, Sassoon D, Kitajewski J. Notch4/int-3, a mammary proto-oncogene, is an endothelial cell-specific mammalian notch gene. Development. 1996;122:2251–2259. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.7.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HU, Chen ZF, Anderson DJ. Molecular distinction and angiogenic interaction between embryonic arteries and veins revealed by ephrin-B2 and its receptor eph-B4. Cell. 1998;93:741–753. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiford BC, Subbarao VD, Mulhern KM. Noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium. Circulation. 2004;109:2965–2971. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000132478.60674.D0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels A, Sedmera D. Developmental anatomy of the heart: A tale of mice and man. Physiological Genomics. 2003;15:165–176. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00033.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JG, ROTH CB, Warkany J. An analysis of the syndrome of malformations induced by maternal vitamin A deficiency. effects of restoration of vitamin A at various times during gestation. Am J Anat. 1953;92:189–217. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000920202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JG, Warkany J. Aortic-arch and cardiac anomalies in the offspring of vitamin A deficient rats. Am J Anat. 1949;85:113–155. doi: 10.1002/aja.1000850106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Bucker S, Jungblut B, Bottger T, Cinnamon Y, Tchorz J, Muller M, Bettler B, Harvey R, Sun QY, Schneider A, Braun T. Inhibition of Notch2 by Numb/Numblike controls myocardial compaction in the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;96:276–285. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JT, Rayburn H, Hynes RO. Cell adhesion events mediated by alpha 4 integrins are essential in placental and cardiac development. Development. 1995;121:549–560. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–137. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Chen H, Wang Y, Yong W, Zhu W, Liu Y, Wagner GR, Payne RM, Field LJ, Xin H, Cai CL, Shou W. Tbx20 transcription factor is a downstream mediator for bone morphogenetic protein-10 in regulating cardiac ventricular wall development and function. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:36820–36829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.279679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Gunput RF, Pasterkamp RJ. Semaphorin signaling: Progress made and promises ahead. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:161–170. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]