Abstract

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are multipotent adult stem cells which are recruited to the tumor microenvironment (TME) and influence tumor progression through multiple mechanisms. In this study, we examined the effects of MSCs on the tunmorigenic capacity of 4T1 murine mammary cancer cells. It was found that MSC-conditioned medium increased the proliferation, migration, and efficiency of mammosphere formation of 4T1 cells in vitro. When co-injected with MSCs into the mouse mammary fat pad, 4T1 cells showed enhanced tumor growth and generated increased spontaneous lung metastasis. Using in vivo fluorescence color-coded imaging, the interaction between GFP-expressing MSCs and RFP-expressing 4T1 cells was monitored. As few as five 4T1 cells could give rise to tumor formation when co-injected with MSCs into the mouse mammary fat pad, but no tumor was formed when five or ten 4T1 cells were implanted alone. The elevation of tumorigenic potential was further supported by gene expression analysis, which showed that when 4T1 cells were in contact with MSCs, several oncogenes, cancer markers, and tumor promoters were upregulated. Moreover, in vivo longitudinal fluorescence imaging of tumorigenesis revealed that MSCs created a vascularized environment which enhances the ability of 4T1 cells to colonize and proliferate. In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the promotion of mammary cancer progression by MSCs was achieved through the generation of a cancer-enhancing microenvironment to increase tumorigenic potential. These findings also suggest the potential risk of enhancing tumor progression in clinical cell therapy using MSCs. Attention has to be paid to patients with high risk of breast cancer when considering cell therapy with MSCs.

Introduction

Mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) are adult stem cells that possess multipotent differentiation potential. In addition to progenies of mesodermal lineages including osteoblasts, chondrocytes, adipose cells and muscle cells [1], MSCs are also able to trans-differentiate into endodermal lineages such as hepatocytes [2]. MSCs primarily reside within the bone marrow [3], but also can be isolated from umbilical cord blood, adipose tissue, adult muscle, and the dental pulp of deciduous baby teeth [4], [5]. Recently, it has been reported that MSCs have multiple effects on cancer progression. When MSCs are systemically injected into tumor-bearing animals, they specifically target tumors [6]-[8]. Factors such as stromal cell-derived factor 1 (SDF-1) and its receptor C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR-4), platelet-derived growth factor α (PDGF-α) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) may be involved in MSC targeting to tumors [9], [10]. The recruited MSCs within the tumor microenvironment (TME) may further differentiate into various types of cells, such as fibroblasts, pericytes and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [11], [12] which influence cancer progression. MSCs also promote angiogenesis. Several growth factors and cytokines secreted by MSCs, such as VEGF, angiopoietin, Interleukin 6, Interleukin 8, transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), PDGF, bFGF, and FGF-7 may act on endothelial cells and directly contribute to tumor vessel formation [13]. Interaction of the chemokine CCL5 and its receptor CCR5 between MSCs and breast cancer cells, respectively, has been shown to enhance cancer cell motility, invasion and metastasis of breast cancer cells [14]. Moreover, MSCs enhanced in vitro mammosphere formation by breast cancer cells and reduced the latency time of in vivo tumor formation [15].

The use of fluorescent proteins for in vivo imaging enables cell behavior to be observed within a living subject. More importantly, the interaction between different types of cells can also be visualized by labeling each type of cell with a different colored fluorescent protein [16]. Using this approach, we previously generated a color-coded TME that allowed imaging of the interaction between cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and metastatic colon cancer in the liver [17]. In the present study, we used color-coded imaging to demonstrate how MSCs affect the gross tumor formation of breast cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Cell Isolation and Culture

Isolation of mouse bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells was performed according to previously reported methods [18] with slight modifications. Briefly, hind tibiae and femurs of transgenic mice ubiquitously expressing GFP or RFP were removed after the animals were sacrificed. Both ends were cut and a marrow plug was flushed out with a 27-gauge needle connected to a syringe filled with complete medium. The marrow was washed with PBS twice and then cultured in DMEM (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum in a 37°C incubator. After 48 hours, unattached cells were removed and then the medium was changed regularly every 3 days. The mouse mammary cancer cell lines, 4T1 and JC, purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and BCRC (Bioresource Collection and Research Centre, Hsinchu, Taiwan), respectively were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Thermal Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

4T1 cells were retrovirally infected with a GFP- or RFP-expressing vector as described previously [19]–[22]. Briefly, a RetroXpress vector (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto. CA, USA), expressing either GFP or RFP, was used for virus production. Retroviruses were packaged using PT67, a NIH3T3-derived packaging cell line and then cultured in DMEM (Thermal Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (Gemini Biological Products, Calabasas, CA, USA). At 20%-confluence, the 4T1 cells were cultured in a 1∶1 mixture of fresh medium and precipitated retroviral supernatant from PT67 cells for 72 h. Fluorescent protein-expressing cells were selected by culturing in medium containing G418, with stepwise concentration increases (from 400 to 1,000 µg/ml). In order to produce the MSC-conditioned medium (MSC-CM), medium used for culturing MSCs for 2 days was collected and kept at 4°C for one day if used immediately, or stored at −20°C for long-term use. The MSC-CM was used to culture 4T1 cells for subsequent experiments.

In vitro Cell Proliferation and Colony Formation

To assess cell proliferation, 104 4T1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured in the presence of either regular medium or MSC-CM. At various time points after cell seeding, cells were released completely by trypsin and viable cells were identified by trypan blue exclusion and counted. To assess colony formation, each well of a 6-well plate was seeded with 500 4T1 cells and cultured in the presence of either regular medium or MSC-CM. After 6 days, the colonies were washed twice with ice-cold PBS and fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 5 min. Crystal violet dissolved in distilled water [0.05% (w/v)] was used to stain the pre-fixed colonies for 20 min. After rinsing with tap water and air-drying, the number of colonies was counted. Only colonies consisting of more than 50 cells were counted.

In vitro Wound Healing Assay

4T1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured with RPMI-1640 medium. When the cells reached confluence, gaps were introduced by scratching, using a micro-pipette tip. After two washings with PBS to remove detached cells and debris, the culture medium was replaced by either MSC-CM, regular medium, or a 1∶1 mixture of MSC-CM and regular medium. Gap closure was monitored and photographed at different time points after scratches were made using an Olympus IX-71 microscope equipped with a Hamamatsu color CCD camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu, Japan). The size of the gaps was measured using Image Pro Plus software.

In vitro Mammosphere Formation

4T1 cells were cultured in regular medium or MSC-CM for 1 week with a change of medium every 2 days. After trypsinization, the presence of a single-cell suspension was confirmed by microscopy. Cells were counted and seeded at 2000 cells/100 µl/well in a 96 well ultra-low-attachment plate (Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA) and cultured with DMEM-F12 medium supplemented with 2% B27 (Gibco-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), 20 ng/ml EGF, 20 ng/ml bFGF, 0.5 mg/ml, hydrocortisone and 5 mg/ml insulin. The number of mammospheres present in each well was counted after culture for 1 week.

Messenger RNA Expression Profiling

GeneChip Mouse genome 430 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA), containing probe sets for >45,000 characterized genes and expressed sequence tags, were used. Sample labeling and processing, GeneChip hybridization, and scanning were performed according to Affymetrix protocols. Briefly, total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Next, cDNA synthesis, fragmentation, hybridization, washing, staining and scanning were performed at the National Research Progress for Genomic Medicine Microarray and Gene Expression Analysis Core Facility, National Yang-Ming University VYM Genome Research Center.

Ethics Statement

All animal studies were approved by the AntiCancer Inc. Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and conducted in accordance with the principles and procedures outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Animals under Assurance No. A3873-01. Animals were kept within a barrier under HEPA filtration. Mice were fed autoclaved laboratory rodent diet (Tecklad LM-485, Western Research Products, Orange, CA, USA). All surgical procedures were performed under anesthesia with an intramuscular injection of 100 µl of a ketamine mixture (10 µl ketamine HCL, 7.6 µl xylazine, 2.4 µl acepromazine maleate, and 10 µl PBS). Euthanasia was achieved either by intraperitoneal injection of an overdose of ketamine mixture or by 100% carbon dioxide inhalation, followed by cervical dislocation.

Tumor Growth

Six-week-old female nude mice were used for the tumor growth study. 5×105 4T1 cells alone or premixed with an equal amount of MSCs were injected into the mammary fat pad of nude mice. Tumor volume (L×W×H×0.52 mm3) was measured twice a week using calipers for 3 weeks. The mice were then euthanized by injection of an overdose of the ketamine mixture when the tumor burden exceeded 10 mm in diameter or when they exhibited significant morbidity.

Spontaneous Lung Metastasis

In order to image spontaneous lung metastasis, 5×105 GFP-expressing 4T1 cells alone or premixed with an equal amount of MSCs were injected into the mammary fat pad of mice. After 3 weeks tumor growth, the mice were sacrificed with an overdose of ketamine mixture. After confirming the death of each mouse, the entire lungs of each mouse were excised, washed with PBS and separated into the various lobes. GFP-fluorescent colonies within each lobe were examined and imaged using an Olympus OV100 Imaging System (Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with a constant exposure time and offset.

Tumorigenesis Assay

Either five, ten, or one hundred RFP-4T1 cells were injected subcutaneously into the mammary fat pad, either alone or with 2×105 GFP-expressing MSCs. Each group consisted of at least five mice. Tumor incidence was recorded for up to 2 months and imaged using the OV-100 imaging system (Olympus). Mice were euthanized when the tumor burden exceeded 10 mm in diameter. To image the process of orthotopic mammary tumor formation, a reversible skin flap was raised according to the method described in [23]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with a ketamine mixture via subcutaneous injection. An arc-shaped incision was made in the thoracic and abdominal skin. The subcutaneous connective tissue was separated to free a skin flap without injuring the vessels. The skin flap was spread and fixed on a flat stand. The mammary fat pad was imaged where the cells were injected with the OV-100 at various magnifications over time.

Immunostaining and TUNEL Assay

Tumors were established by orthotopic implantation of 5×105 4T1 cells alone or with equal amount of MSCs as described above. Tumors were excised and immediately soaked in 30% sucrose (in PBS) at 4°C overnight. For cryosectioning, tissues were embedded in OCT compound and stored at −80°C. The sectioned tissue slices were blocked and permeabilized by blocking buffer (5% FBS and 0.03% Triton X 100 in PBS) for 1 hour. Immunofluorescence staining was performed by incubating tissue samples with primary antibodies (diluted in PBS containing 5% PBS) at 4°C overnight. After rinsing with PBS, tissue samples were incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 hr followed by DAPI counterstaining. Samples were viewed and imaged by fluorescence microscopy. Antibodies used in this study included rat anti-CD31 monoclonal Ab (1∶100, ab7388, Abcam); rabbit anti-Ki67 polyclonal Ab (1∶100, ab15580, Abcam); DyLightTM488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Ab (1∶500, 112-175-062, Jackson ImmunoResearch); and CyTM5-conjugated goat anti-rat Ab (1∶500, 111-485-003, Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Results

MSCs Enhance 4T1 Cancer Cell Proliferation and Tumor Growth

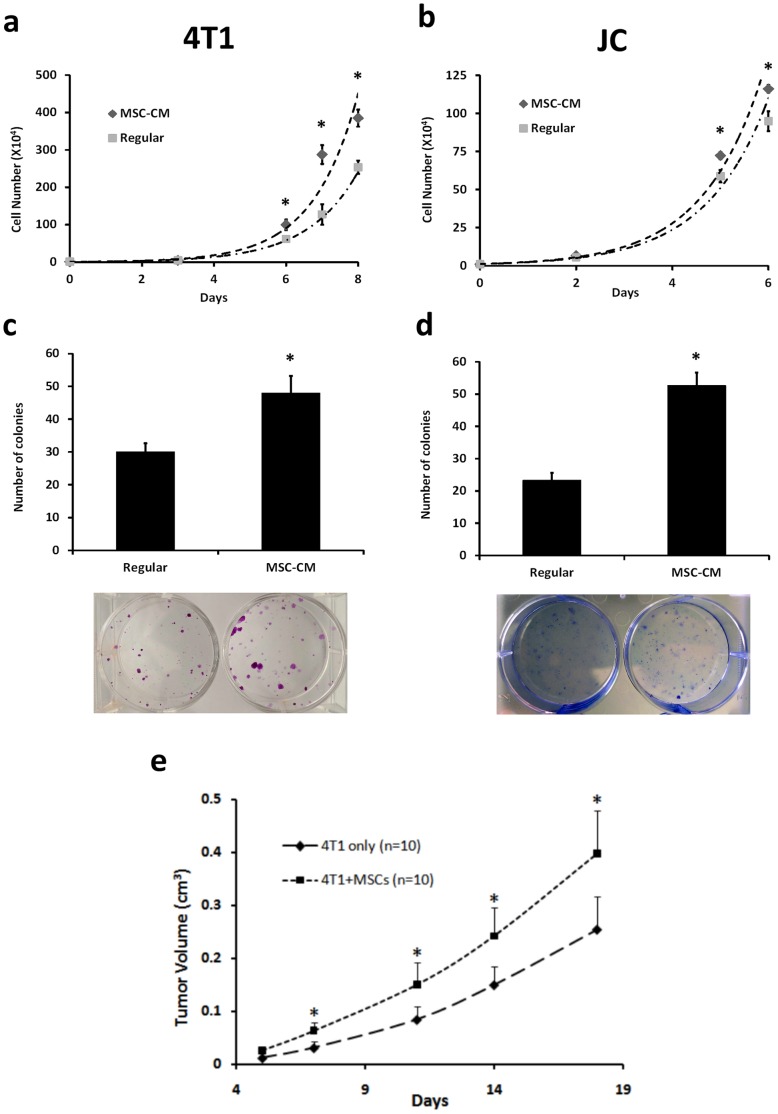

To determine whether MSCs influence cancer cell proliferation, cells were counted at various time points after 4T1 or JC cells were cultured in regular medium or MSC-CM. Cells cultured in MSC-CM proliferated more than cells cultured in regular medium (Fig. 1a and 1b, p<0.05). In addition, using the colony-forming assay, cells cultured in MSC-CM formed more colonies than those in regular medium (Fig. 1c and 1d, p<0.05).

Figure 1. MSC enhances 4T1 cell proliferation and tumor growth.

(a,b) To assess cell proliferation, 4T1 or JC cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium or MSC-CM with the medium changed every 2 days. Cells were counted from 6 wells at each time point after culture at the indicated time points. Cells cultured in CM proliferated more than those cultured in regular medium. (c, d) To carry out the colony forming assay, 500 4T1 or JC cells were seeded and cultured using RPMI-1640 medium or MSC-CM. The colonies were stained with crystal violet after being cultured for 6 days. The cells grown using MSC-CM showed greater potential to form colonies. (c) 5×105 GFP-expressing 4T1 cells alone or premixed with an equal amount of RFP-expressing MSCs were injected subcutaneously into the mammary fat pad of nude mice. Each group consisted of ten mice. Tumor growth was measured twice a week and the data are shown as the mean ± SD. Tumors derived from a mixture of 4T1 cells and MSCs had significantly enhanced growth compared to tumors derived from 4T1 cells alone. All data are shown as the mean ± SD. “*” represents a significant difference of p<0.05.

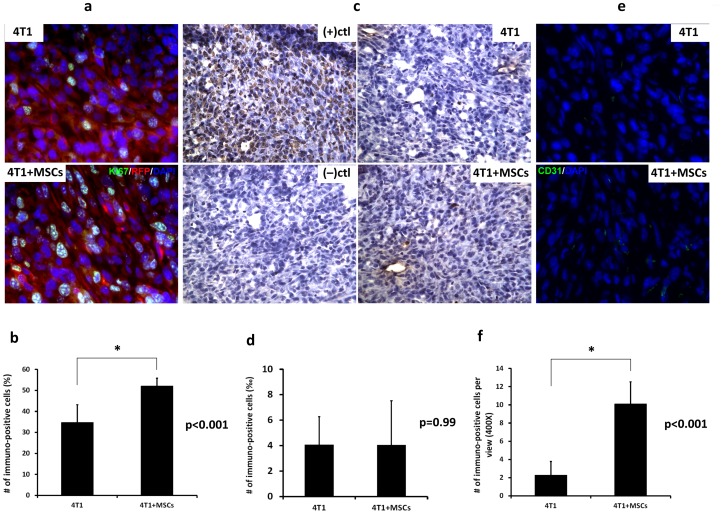

In order to investigate the effect of MSCs on tumor growth, 4T1 cells alone or pre-mixed with MSCs were injected into the mammary fat pad of mice and tumor volume was measured. On day 18, tumors formed from 4T1+MSC cell co-transplantation were 1.5-fold larger than the tumors derived from 4T1 cells alone. There was a significant difference in tumor volume between these two groups from day 7 after cell implantation (Fig. 1e, *p<0.02). Immunostaining of tumor sections also showed that the frequency of Ki67 expression was significantly higher in 4T1 cancer cells derived from 4T1+MSC tumors than those from 4T1 cells (Fig. 2a and 2b). These results indicated that co-implantation with MSCs resulted in the increase of proliferation in 4T1 cells and tumor-growth enhancement.

Figure 2. Tumor immunostaining for proliferation, apoptosis and angiogenesis.

5×105 GFP-expressing 4T1 cells alone or premixed with an equal amount of RFP-expressing MSCs were injected subcutaneously into the mammary fat pad of nude mice. Tumors were excised for subsequent sectioning and immunostaining. Tumor sections from a 4T1 tumor or a 4T1+MSCs tumor were stained with antibody raised against Ki67 (a), CD31 (e) or subjected to TUNEL assay (c). (b, d and f) Quantification of Ki67, CD31 and TUNEL staining of tumor sections from a 4T1 tumor or a 4T1+MSCs tumor. Data represent mean values ±SD (n = 3). “*” represents a significant difference of p<0.001.

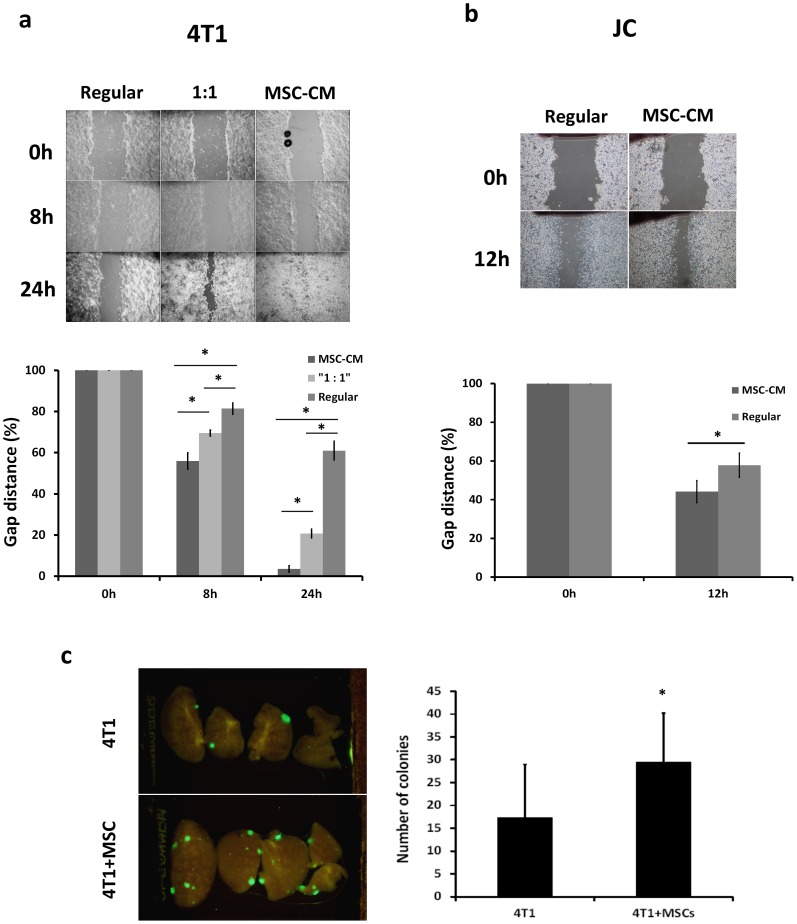

MSCs Promote Cancer Cell Migration in vitro and Lung Metastasis in vivo

To assess the influence of MSCs on cancer cell migration, 4T1 or JC cells cultured in MSC-CM or regular medium were subjected to a wound-healing assay. Higher migration ability was observed when cancer cells were cultured in MSC-CM compared to regular medium (Fig. 3a and 3b) (*p<0.001). For 4T1 cells, the average gap distance in regular medium and MSC-CM narrowed to 81% and 56%, respectively, at 8 hr; and to 61% and 4%, respectively, at 24 hr (Fig. 3a). A similar effect was shown in JC cells, with the gap narrowed to 57% and 44%, respectively, of the original size at 12 hr when cells were in regular medium and MSC-CM, respectively (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3. MSC-CM enhances 4T1 cell migration and lung metastasis.

(a,b) Representative photomicrographs of the gaps of 4T1 and JC cells for each culture condition at different time points after scratching in a wound healing assay (upper). Quantification of wound-healing was assessed by measuring gap distance (lower). The cells showed a higher migratory ability when cultured in MSC-CM compared to cells cultured in RPMI-1640 medium. Data are presented as the percentage change in gap distance relative to 0 hr. Each bar shows mean ± SD of six measurements of each gap. Asterisk indicates a significant difference using the Student’s t test. (*p<0.05) (c) For the in vivo lung metastasis assay, 5×105 GFP-expressing 4T1 cells alone, or premixed with an equal number of MSCs, were injected into the mammary fat pad. Each group contained at least nine mice. Three weeks later, the mice were sacrificed and their lungs excised and then imaged using the Olympus OV100 Imaging System with a constant exposure time and offset. Representative fluorescence images of the various lobes derived from the same lung. Lung tissue was excised from mice bearing 4T1 (right panel, n = 10) or 4T1+MSCs (left panel, n = 9) tumors. (d) Calculated number of GFP-fluorescent lung colonies. The number of colonies present in five lobes per lung, from both lungs was counted. MSCs promote spontaneous lung metastasis of orthotopic 4T1 tumors. Data are presented as mean ± SD with a significant difference (p = 0.03).

MSCs also enhanced spontaneous metastasis of 4T1 tumors. We injected 5×105 GFP-expressing 4T1 cells alone or pre-mixed with 5×105 MSCs into the mammary fat pad of nude mice. GFP-expressing colonies in lung tissue were counted 3 weeks later. The tumors formed by co-injection gave rise to 29.6±11.5 spontaneous lung metastatic colonies, compared to 17.4±10.7 lung colonies produced by 4T1 cells alone (p = 0.03) (Fig. 3c).

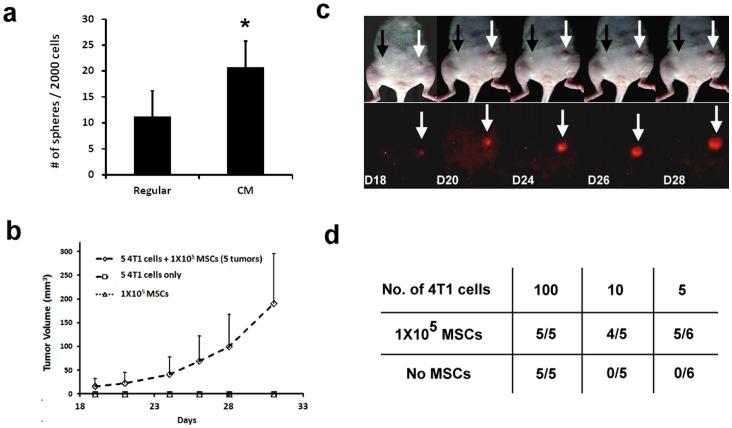

MSCs Promote Mammosphere Formation and Tumorigenesis

Tumor sphere formation may depend on self-renewal of cancer stem cells and correlates with in vivo tumorigenic capacity. To determine whether MSCs influence sphere-forming ability, 4T1 cells were pre-cultured in either regular medium or MSC-CM for 1 week and then subjected to a mammosphere forming assay. 4T1 cells pre-cultured with MSC-CM formed mammospheres more efficiently than cells pre-cultured in regular medium (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4. MSCs enhance 4T1 mammosphere formation and tumorigenicity.

For the mammosphere formation assay, 4T1 cells were cultured in regular medium or MSC-CM for 1 week. After typsinization, a single-cell suspension was confirmed by microscopic observation. The cells were then seeded at 2000 cells/100 µl/well into 96 well ultra-low-attachment plates and cultured in mammosphere-forming medium. The number of spheres formed was counted after 1 week incubation. (a) Number of spheres formed from 2000 cells pre-cultured with RPMI-1640 or MSC-CM and counted from five wells. Cells pre-cultured in MSC-CM formed mammospheres more efficiently than those cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (p = 0.03). Data are presented as the mean ± SD. To evaluate the in vivo tumorigenic potential of 4T1 cell, a total of either 5, 10 or 100 RFP-expressing 4T1 cells alone or premixed with 1×105 GFP-expressing MSCs, were injected into the mammary fat pad. Tumor incidence was observed and imaged. (b) Representative image of tumorigenesis. The white and black arrows indicate the sites where 4T1 cells mixed with MSCs or 4T1 cells alone were injected, respectively. Tumor growth was recorded and is shown in (b). (c) Summary of tumor formation when analyzed using limiting dilution.

We further investigated the effect of MSCs on 4T1 tumorigenesis in vivo. Either 100, 10 or 5 RFP-expressing 4T1 cells alone or pre-mixed with 1×105 GFP-expressing MSC cells were injected subcutaneously into the mammary fat pad. One hundred 4T1 cells gave rise to tumors whether or not co-injected with MSCs. However, when either five or ten cells were injected, 4T1 cells formed tumors only when MSCs were present (Fig. 4). MSCs implanted alone did not result in tumor formation (Fig. 4b). Longitudinal in vivo fluorescence imaging demonstrated that during tumor formation (D18 to D28), only the RFP signal from the 4T1 cells was observed and not the GFP signal from MSCs, which supports the hypothesis that MSCs undergo no or negligible proliferation during the process of 4T1 tumorigenesis (Fig. 4c). These results clearly showed that 4T1 cells increased their ability of self-renewal and tumorigenic potential after modulation by MSCs.

In vivo Imaging of MSC-4T1 Cell-cell Interaction

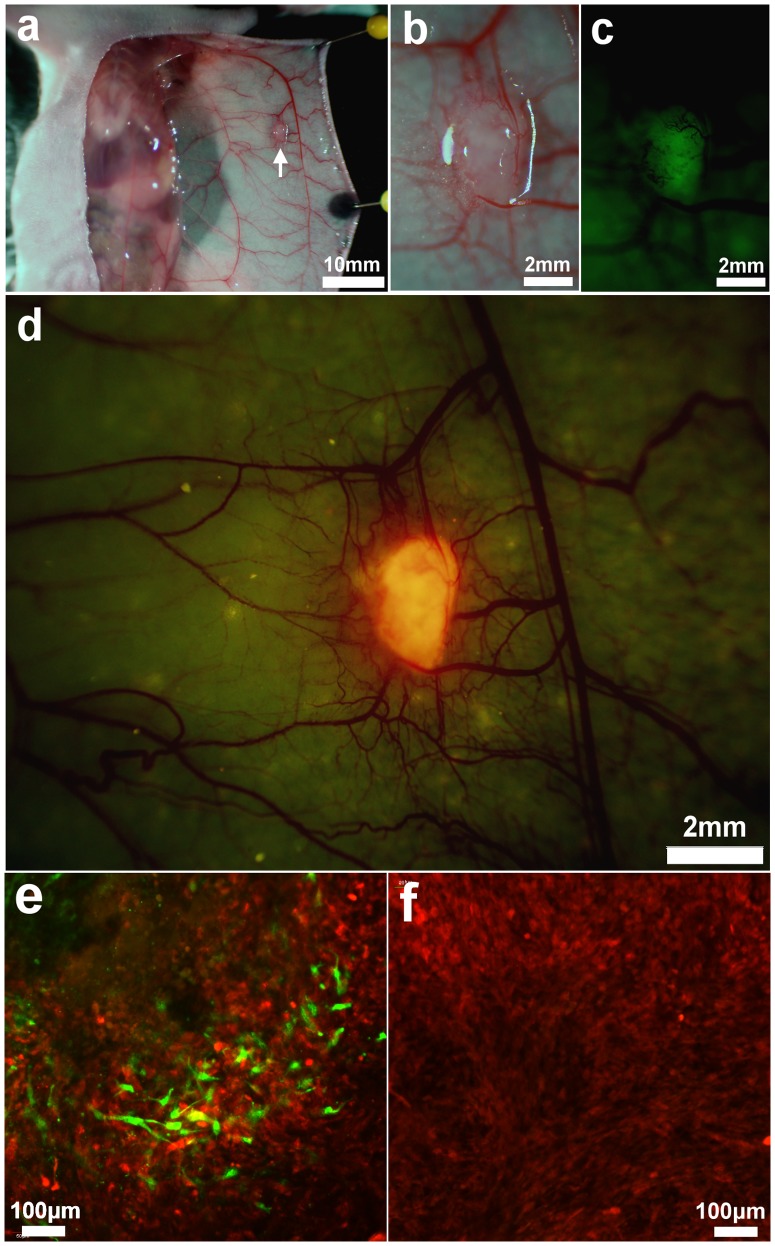

To investigate the cellular interaction between 4T1 cell and MSCs in vivo, RFP-expressing 4T1 cells and GFP-expressing MSCs were co-implanted into the mouse mammary fat pad using 1×105 of each cell type. One week after implantation, an arc-shape incision was made into the abdominal skin. The skin flap was raised above the mammary fat pad and imaged with the OV-100. At 1∼2 mm diameter, the tumor was visualized close to the epigastric cranialis vein, which had a thickened diameter. A dense vessel complex formed at the site of the tumor. Under fluorescence-light excitation, the tumor emitted both GFP and RFP signals from MSCs and 4T1 cells, respectively (Fig. 5a∼c). A cross-section of an excised tumor was immediately imaged using the Olympus IV100 laser-scanning microscope. GFP-expressing MSCs appeared fibroblastic with multiple protrusions which were dispersed among the RFP-expressing 4T1 cells within the tumor. The number of GFP-expressing MSCs was much lower than the RFP-expressing 4T1 cells, even though both types of cells were co-implanted with equal numbers (Fig. 5e). On day 11, when tumor volume was approximately 100 mm3, GFP-MSCs could rarely be seen (Fig. 5f) within the tumor, suggesting that the MSCs were not proliferating.

Figure 5. In vivo imaging of MSC-4T1 cell-cell interaction.

GFP-expressing MSCs and RFP-expressing 4T1 cells (5×105 each) were co-implanted into the mouse thoracic mammary fat pad. (a) 5 days after implantation, an arc shape incision was made in the abdominal skin. A skin flap was lifted above the mammary fat pad and imaged with the OV-100. White arrow indicates the location of tumor. (b–d). GFP and RFP signals were detected from the tumor which was surrounded by a dense vascular network. (e) The excised tumor was cross-sectioned and imaged using the Olympus IV100. GFP and RFP-expressing cells were observed within the tumor. (f) On day 11, GFP-MSCs were rarely observed within the tumor, suggesting MSCs were not proliferating during the growing of tumor.

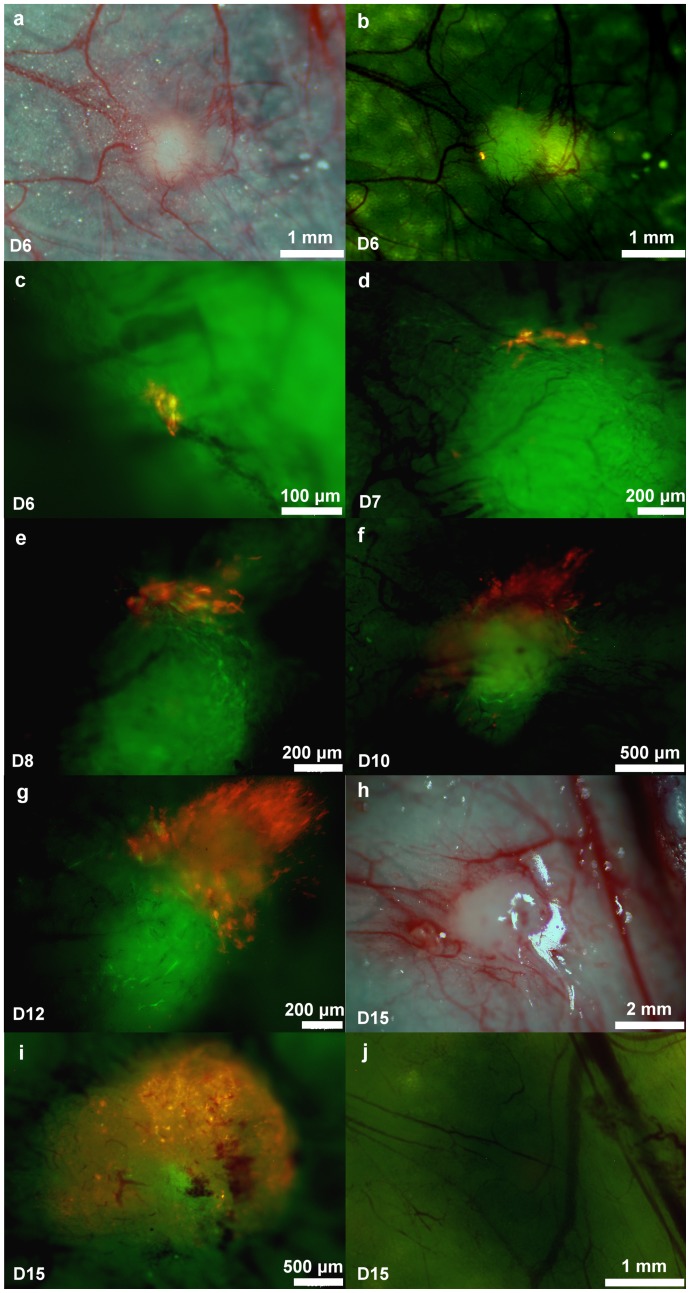

The process of 4T1 tumor initiation in the presence of MSCs was also imaged. Ten RFP-expressing 4T1 cells and 1×105 GFP-expressing MSCs were co-implanted into the mouse mammary fat pad. On day 6 after injection, a GFP fluorescence-emitting MSC spherical mass was observed. Numerous tiny blood vessels stretched from outside the vascular trunk into the mass and formed an initial vessel network. Only a low RFP signal was detected within the mass. At higher magnification, approximately 6 RFP-expressing 4T1 cells were imaged (Fig. 6a∼c). On day 7, more RFP-expressing cells were observed within the sphere (Fig. 6d). After day 8, the number of 4T1 cells increased, and there was significant proliferation of these cells by day 15 (Fig. 6e∼k). When 10 RFP-expressing 4T1 cells were implanted alone, no cells were found later at or near the area of injection (Fig. 6l).

Figure 6. In vivo imaging of 4T1 tumorigenesis.

Ten RFP-expressing 4T1 cells were injected alone or co-injected with 1×105 GFP-expressing MSCs. An arc-shaped incision was made in the thoracic and abdominal skin and imaged with the OV-100 over time. (a∼k) Tumor initiation by ten 4T1 cells in the presence of MSCs was monitored. (l) No tumor incidence was found when 10 4T1 cells without MSCs were injected.

Gene Expression Array Analysis and Immunochemistry

Comparing the relative gene expression levels of 4T1 cells which have been co-cultured with MSCs to 4T1 cells alone, 1270 genes that showed a change greater than two-fold were identified. A total of 684 upregulated genes were analyzed using gene ontology clustering based on DAVID Bioinformatics Resources (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov). The clustered upregulated functional groups included genes encoding proteins related to the positive regulation of apoptosis (n = 22), the negative regulation of apoptosis (n = 14) (Table 1), the positive regulation of proliferation (n = 16), and the negative regulation of proliferation (n = 14) (Table 2). These data suggest that co-culture with MSCs induces opposing effects on both 4T1 cell proliferation and apoptosis at the gene expression level. Despite the complex gene expression pattern induced by MSCs, 4T1 cells or tumors showed enhanced cell proliferation and tumor growth in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2a). Apoptosis was also assessed in tumors derived from implantation of 4T1 with or without MSCs. The result showed no difference between the two groups (Fig. 2c and 2d), suggesting that MSC-induced upregulation of pro-apoptotic genes did not trigger cell apoptosis. Among the upregulated genes, we identified several oncogenes (Ets2, Fyn, Fos, Rab30 and Src), various tumor markers (Cyp1b1, Gpa33, Cd47, Fam129a, st7l, chka, Lgalsbp, Antxr1 and Ly6a) and other genes related to tumor promotion (Cxcl10, Trim25, Grn, Foxc2, Bmp7 and Irs1) (Table 3). These upregulated genes help to partly explain enhanced tumor growth, despite the fact that the 4T1 cells also express higher level of genes related to apoptosis and negative regulation of proliferation. In summary, the gene expression profile of the 4T1 cells suggests that MSCs are able to induce multiple effects on 4T1 cells, including some that oppose each other.

Table 1. Cluster of genes involved in the positive and negative regulation of apoptosis.

| ID | Gene Title | Gene Symbol | Fold Change |

| Positive Regulation of Apoptosis | |||

| 1423315_at | BCL2 binding component 3 | Bbc3 | 2.639015822 |

| 1418901_at | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), beta | Cebpb | 2.639015822 |

| 1417516_at | DNA-damage inducible transcript 3 | Ddit3 | 7.464263932 |

| 1460251_at | Fas (TNF receptor superfamily member 6) | Fas | 5.278031643 |

| 1418242_at | Fas-associated factor 1 | Faf1 | 2 |

| 1416029_at | Kruppel-like factor 10 | Klf10 | 3.482202253 |

| 1450918_s_at | Rous sarcoma oncogene | Src | 2 |

| 1435479_at | bone morphogenetic protein 7 | Bmp7 | 3.031433133 |

| 1449591_at | caspase 4, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase | Casp4 | 9.18958684 |

| 1426955_at | collagen, type XVIII, alpha 1 | Col18a1 | 2.143546925 |

| 1437119_at | endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to nucleus signalling 1 | Ern1 | 3.482202253 |

| 1434831_a_at | forkhead box O3 | Foxo3 | 2.143546925 |

| 1419665_a_at | nuclear protein 1 | Nupr1 | 3.732131966 |

| 1457635_s_at | nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group C, member 1 | Nr3c1 | 2 |

| 1459137_at | promyelocytic leukemia | Pml | 2.462288827 |

| 1423986_a_at | shisa homolog 5 (Xenopus laevis) | Shisa5 | 2.29739671 |

| 1426538_a_at | transformation related protein 53 | Trp53 | 2.828427125 |

| 1416926_at | transformation related protein 53 inducible nuclear protein1 | Trp53inp1 | 3.249009585 |

| 1437277_x_at | transglutaminase 2, C polypeptide | Tgm2 | 8 |

| 1420499_at | GTP cyclohydrolase 1 | Gch1 | 2.091825876 |

| 1419603_at | interferon activated gene 204///myeloid cell nuclear differentiation antigen | Ifi204 | 2.078920986 |

| 1450922_a_at | transforming growth factor, beta 2 | Tgfb2 | 2.016764064 |

| Negative Regulation of Apoptosis | |||

| 1418901_at | CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), beta | Cebpb | 2.639015822 |

| 1425519_a_at | CD74 antigen | Cd74 | 3.249009585 |

| 1460251_at | Fas (TNF receptor superfamily member 6) | Fas | 5.278031643 |

| 1420772_a_at | TSC22 domain family, member 3 | Tsc22d3 | 3.482202253 |

| 1425927_a_at | activating transcription factor 5 | Atf5 | 3.249009585 |

| 1451083_s_at | alanyl-tRNA synthetase | Aars | 2 |

| 1449591_at | caspase 4, apoptosis-related cysteine peptidase | Casp4 | 9.18958684 |

| 1416693_at | forkhead box C2 | Foxc2 | 2.143546925 |

| 1416983_s_at | forkhead box O1 | Foxo1 | 2.143546925 |

| 1454958_at | glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta | Gsk3b | 2.143546925 |

| 1438930_s_at | methyl CpG binding protein 2 | Mecp2 | 2 |

| 1437122_at | B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 | Bcl2 | 2.639015822 |

| 1422601_at | serine (or cysteine) peptidase inhibitor, clade B, member 9 | Serpinb9 | 2.639015822 |

| 1426538_a_at | transformation related protein 53 | Trp53 | 2.828427125 |

Results presented show genes with more than 2-fold increase in expression in 4T1 cells following contact co-culture with MSCs.

Table 2. Cluster of genes involved in the positive and negative regulation of proliferation.

| ID | Gene Title | Gene Symbol | Fold Change | ||

| Positive Regulation of Proliferation | |||||

| 1451021_a_at | Kruppel-like factor 5 | Klf5 | 2.143546925 | ||

| 1418930_at | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 | Cxcl10 | 5.278031643 | ||

| 1426955_at | collagen, type XVIII, alpha 1 | Col18a1 | 2.143546925 | ||

| 1416123_at | cyclin D2 | Ccnd2 | 2.143546925 | ||

| 1422738_at | discoidin domain receptor family, member 2 | Ddr2 | 2.828427125 | ||

| 1435888_at | epidermal growth factor receptor | Egfr | 3.732131966 | ||

| 1448148_at | granulin | Grn | 3.031433133 | ||

| 1423104_at | insulin receptor substrate 1 | Irs1 | 2.143546925 | ||

| 1437303_at | interleukin 6 signal transducer | Il6st | 2.29739671 | ||

| 1438930_s_at | methyl CpG binding protein 2 | Mecp2 | 2 | ||

| 1419123_a_at | platelet-derived growth factor, C polypeptide | Pdgfc | 4.59479342 | ||

| 1437122_at | B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 | Bcl2 | 2.639015822 | ||

| 1454974_at | netrin 1 | Ntn1 | 2.209770534 | ||

| 1437247_at | fos-like antigen 2 | Fosl2 | 2.328358707 | ||

| 1450922_a_at | transforming growth factor, beta 2 | Tgfb2 | 2.016764064 | ||

| 1417500_a_at | transglutaminase 2, C polypeptide | Tgm2 | 7.464263932 | ||

| Negative Regulation of Proliferation | |||||

| 1417394_at | Kruppel-like factor 4 (gut) | Klf4 | 3.031433133 | ||

| 1435479_at | bone morphogenetic protein 7 | Bmp7 | 3.031433133 | ||

| 1440866_at | eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 2 | Eif2ak2 | 4 | ||

| 1454693_at | histone deacetylase 4 | Hdac4 | 2.828427125 | ||

| 1423754_at | interferon induced transmembrane protein 3 | Ifitm3 | 2.639015822 | ||

| 1419665_a_at | nuclear protein 1 | Nupr1 | 3.732131966 | ||

| 1437122_at | B-cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 | Bcl2 | 2.639015822 | ||

| 1459137_at | promyelocytic leukemia | Pml | 2.462288827 | ||

| 1417850_at | retinoblastoma 1 | Rb1 | 2.143546925 | ||

| 1450165_at | schlafen 2 | Slfn2 | 3.031433133 | ||

| 1430526_a_at | SWI/SNF related, matrix associated, actin dependent regulator ofchromatin, subfamily a, member 2 | Smarca2 | 1.611863831 | ||

| 1416168_at | serine (or cysteine) proteinase inhibitor, clade F, member 1 | Serpinf1 | 2.561671254 | ||

| 1426538_a_at | transformation related protein 53 | Trp53 | 2.828427125 | ||

| 1450922_a_at | transforming growth factor, beta 2 | Tgfb2 | 2.016764064 | ||

Results presented show genes with more than 2-fold increase in expression in 4T1 cells following contact co-culture with MSCs.

Table 3. Genes classified into oncogenes, tumor markers and tumor promoters.

| ID | Gene Title | Gene Symbol | Fold Change | |

| Oncogene | ||||

| 1416268_at | E26 avian leukemia oncogene 2, 3′ domain | Ets2 | 2.462288827 | |

| 1417558_at | Fyn proto-oncogene | Fyn | 2.828427125 | |

| 1423100_at | FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene | Fos | 4.28709385 | |

| 1426452_a_at | RAB30, member RAS oncogene family | Rab30 | 2.143546925 | |

| 1450918_s_at | Rous sarcoma oncogene | Src | 2 | |

| Tumor Marker | ||||

| 1416612_at | cytochrome P450, family 1, subfamily b, polypeptide 1 | Cyp1b1 | 2.462288827 | |

| 1419330_a_at | glycoprotein A33 (transmembrane) | Gpa33 | 4 | |

| 1419554_at | CD47 antigen (Rh-related antigen, integrin-associated signal transducer) | Cd47 | 2.143546925 | |

| 1422567_at | family with sequence similarity 129, member A | Fam129a | 6.964404506 | |

| 1448380_at | lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble, 3 binding protein | Lgals3bp | 3.249009585 | |

| 1450264_a_at | choline kinase alpha | Chka | 4 | |

| 1451446_at | anthrax toxin receptor 1 | Antxr1 | 4 | |

| 1417185_at | lymphocyte antigen 6 complex, locus A | Ly6a | 4.924577653 | |

| Tumor Promoter | ||||

| 1418930_at | chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 10 | Cxcl10 | 5.278031643 | |

| 1419879_s_at | tripartite motif-containing 25 | Trim25 | 2.143546925 | |

| 1438629_x_at | granulin | Grn | 2.29739671 | |

| 1416693_at | forkhead box C2 | Foxc2 | 2.143546925 | |

| 1418910_at | bone morphogenetic protein 7 | Bmp7 | 2.29739671 | |

| 1423104_at | insulin receptor substrate 1 | Irs1 | 2.143546925 | |

| 1416016_at | transporter 1, ATP-binding cassette, sub-family B (MDR/TAP) | Tap1 | 6.964404506 | |

| 1441026_at | poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase family, member 4 | Parp4 | 3.249009585 | |

Results presented show genes with more than 2-fold increase in expression in 4T1 cells following contact co-culture with MSCs.

Discussion

MSCs within the tumor microenvironment exert multiple tumorigenic effects such as enhancement of tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis [24]. In this study, we used murine MSCs and 4T1 mammary cancer cells to determine how MSCs affect tumor progression. MSCs enhanced 4T1 tumor growth and lung metastasis when co-injected into the mouse mammary fat pad (Fig. 1 and 3). MSCs significantly increased the tumorigenic potential of 4T1 cells in vivo. When co-injected with MSCs, only five or ten 4T1 cells could form orthotopic tumors.When co-cultured with MSCs, 4T1 cells had upregulated expression of several oncogenes and tumor promoting genes. We propose that MSCs are able to affect the cancer cells, thereby allowing them to become tumorigenic, possibly by modulating their gene expression. These results suggest that through modulation by MSCs, 4T1 cancer cells acquire higher self-renewal ability, which is an important characteristic of cancer stem cells. Other studies have shown that MSCs enhance the cancer stem cell population in vitro [25], [26]. These results indicate a high risk of breast cancer when performing cell therapy with MSCs.

Initiation is a crucial process in tumor formation. Subcutaneous tumors become palpable when the diameter reaches approximately 5 mm and at this time the cell number within the tumor could exceed 1×108. Due to the limited resolution of clinical imaging, the early stage of tumorigenesis is difficult to detect. Fluorescence imaging using color-coded cells, together with an in vivo imaging system, is able to clearly visualize the morphological changes in cancer cells that occur during tumor progression, migration or interaction within the stroma at the single-cell level [27]. In addition to observation of the gross tumor, the imaging technology described in this report enables in vivo single-cell level visualization of response to cancer treatment.

In the present study, we co-injected either 5 or 10 RFP-4T1 cells and 105 GFP-MSCs to monitor the process of 4T1 tumorigenesis in vivo. With longitudinal colored-coded fluorescence imaging, these few RFP-expressing 4T1 cells initially resided in the GFP-expressing MSC-mass and retained their viability, suggesting that MSCs create a microenvironment favoring cancer cell survival and eventual proliferation. The proliferation of RFP-expressing 4T1 cells increased over time and by day 15, the cancer cells had grown and were distributed within the MSC-mass.

The promoting effect of MSCs on tumor growth is related to increased tumor vessel formation [28]. Several factors secreted by MSCs are also known to influence angiogenesis, including FGF, MCP1, PDGF-α and VEGF [29]–[32]. Our results further provide the image-based evidence that MSCs create a vascularized microenvironment. Co-implantation of 105 GFP-expressing MSCs in the mouse mammary fat pad produced a spherical mass of approximately 1 mm in diameter that was comprised mainly of MSCs after 6 days. Surrounding vessels increased and many of them were distributed within the MSCs mass. The vessels become thicker and increased in number over time (Fig. 6a, 6b and 6j). CD31, an endothelial marker, could also be detected to a greater extent in tumors derived from 4T1+MSCs than in tumors from 4T1 alone (Fig. 2e and 2f). These results demonstrated that MSCs increased tumor angiogenesis, suggesting that MSCs affect both cancer cells and the tumor microenvironment.

Conclusions

Our results indicate that MSCs promote mammary tumorigenesis, tumor growth and metastasis, possibly by modifying cancer-related gene expression and generating a vascularized microenvironment. The above findings suggest that MSCs in the tumor microenvironment may be a potential target for developing strategies of cancer therapy in the future. Care must be taken when considering MSC therapy in patients with a high risk of breast cancer.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Taiwan Mouse Clinic, which is funded by the National Research Program for Biopharmaceuticals (NRPB) at the National Science Council (NSC) of Taiwan, for technical support in animal experiments.

Funding Statement

This work was supported in part by the UST-UCSD International Center of Excellence in Advanced Bio-engineering sponsored by the Taiwan National Science Council I-RiCE Program under Grant Number: NSC100-2911-I-009-101. The authors also acknowledge financial support from the Taipei Veterans General Hospital (VGH100E1-010, VGH100C-056, VN100-05,VGH100D-003-2 and V99ER2-013), the National Science Council, Taiwan (NSC100-2120-M-010-001, NSC100-2314-B-010-030-MY3, NSC100-2321-B-010-019, NSC99-3111-B-010-002, NSC98-2314-B-010-001-MY3, NSC 99-2911-I-010-501, NSC 99-3114-B-002-005 and NSC98-2911-I-010-009) and the Department of Health (DOH100-TD-C-111 -007). This study was also supported by a grant from the Ministry of Education, Aim for the Top University Plan, a US National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant CA132971 and a Taipei medical University, Wan-Fang Hospital grant 102swf02.

References

- 1. Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, et al. (1999) Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science 284: 143–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee KD, Kuo TK, Whang-Peng J, Chung YF, Lin CT, et al. (2004) In vitro hepatic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Hepatology 40: 1275–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Phinney DG, Kopen G, Isaacson RL, Prockop DJ (1999) Plastic adherent stromal cells from the bone marrow of commonly used strains of inbred mice: variations in yield, growth, and differentiation. J Cell Biochem 72: 570–585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kern S, Eichler H, Stoeve J, Kluter H, Bieback K (2006) Comparative analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, or adipose tissue. Stem Cells 24: 1294–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee OK, Kuo TK, Chen WM, Lee KD, Hsieh SL, et al. (2004) Isolation of multipotent mesenchymal stem cells from umbilical cord blood. Blood 103: 1669–1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Studeny M, Marini FC, Dembinski JL, Zompetta C, Cabreira-Hansen M, et al. (2004) Mesenchymal stem cells: potential precursors for tumor stroma and targeted-delivery vehicles for anticancer agents. J Natl Cancer Inst 96: 1593–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nakamizo A, Marini F, Amano T, Khan A, Studeny M, et al. (2005) Human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of gliomas. Cancer Res 65: 3307–3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kidd S, Spaeth E, Dembinski JL, Dietrich M, Watson K, et al. (2009) Direct evidence of mesenchymal stem cell tropism for tumor and wounding microenvironments using in vivo bioluminescent imaging. Stem Cells 27: 2614–2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spaeth E, Klopp A, Dembinski J, Andreeff M, Marini F (2008) Inflammation and tumor microenvironments: defining the migratory itinerary of mesenchymal stem cells. Gene Ther 15: 730–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schichor C, Birnbaum T, Etminan N, Schnell O, Grau S, et al. (2006) Vascular endothelial growth factor A contributes to glioma-induced migration of human marrow stromal cells (hMSC). Exp Neurol 199: 301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kidd S, Spaeth E, Klopp A, Andreeff M, Hall B, et al. (2008) The (in) auspicious role of mesenchymal stromal cells in cancer: be it friend or foe. Cytotherapy 10: 657–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mishra PJ, Humeniuk R, Medina DJ, Alexe G, Mesirov JP, et al. (2008) Carcinoma-associated fibroblast-like differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Cancer Res 68: 4331–4339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feng B, Chen L (2009) Review of mesenchymal stem cells and tumors: executioner or coconspirator? Cancer Biother Radiopharm 24: 717–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Karnoub AE, Dash AB, Vo AP, Sullivan A, Brooks MW, et al. (2007) Mesenchymal stem cells within tumour stroma promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature 449: 557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klopp A, Lacerda L, Gupta A, Debeb B, Solley T, et al.. (2010) Mesenchymal stem cells promote mammosphere formation and decrease E-cadherin in normal and malignant breast cells. PLoS One 5, e12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16. Hoffman R (2005) The multiple uses of fluorescent proteins to visualize cancer in vivo. Nature Reviews Cancer 5: 796–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Suetsugu A, Osawa Y, Nagaki M, Saji S, Moriwaki H, et al. (2011) Imaging the recruitment of cancer-associated fibroblasts by liver-metastatic colon cancer. J Cell Biochem 112: 949–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Soleimani M, Nadri S (2009) A protocol for isolation and culture of mesenchymal stem cells from mouse bone marrow. Nat Protoc 4: 102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hoffman RM, Yang M (2006) Subcellular imaging in the live mouse. Nat Protoc 1: 775–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hoffman RM, Yang M (2006) Color-coded fluorescence imaging of tumor-host interactions. Nat Proc 1: 928–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hoffman RM, Yang M (2006) Whole-body imaging with fluorescent proteins. Nat Protoc 1: 1429–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li X, Wang J, An Z, Yang M, Baranov E, et al. (2002) Optically imageable metastatic model of human breast cancer. Clin Exp Metastasis 19: 347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Yamauchi K, Yang M, Jiang P, Xu M, Yamamoto N, et al. (2006) Development of real-time subcellular dynamic multicolor imaging of cancer-cell trafficking in live mice with a variable-magnification whole-mouse imaging system. Cancer Res 66: 4208–4214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dai LJ, Moniri MR, Zeng ZR, Zhou JX, Rayat J, et al. (2011) Potential implications of mesenchymal stem cells in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett 305: 8–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu S, Ginestier C, Ou SJ, Clouthier SG, Patel SH, et al. (2011) Breast cancer stem cells are regulated by mesenchymal stem cells through cytokine networks. Cancer Res 71: 614–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McLean K, Gong Y, Choi Y, Deng N, Yang K, et al. (2011) Human ovarian carcinoma-associated mesenchymal stem cells regulate cancer stem cells and tumorigenesis via altered BMP production. J Clin Invest 121: 3206–3219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yang M, Li L, Jiang P, Moossa AR, Penman S, et al. (2003) Dual-color fluorescence imaging distinguishes tumor cells from induced host angiogenic vessels and stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100: 14259–14262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tian LL, Yue W, Zhu F, Li S, Li W (2011) Human mesenchymal stem cells play a dual role on tumor cell growth in vitro and in vivo. J Cell Physiol 226: 1860–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lai RC, Arslan F, Lee MM, Sze NS, Choo A, et al. (2010) Exosome secreted by MSC reduces myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res 4: 214–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen TS, Lai RC, Lee MM, Choo AB, Lee CN, et al. (2010) Mesenchymal stem cell secretes microparticles enriched in pre-microRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 215–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jin L, Tabe Y, Konoplev S, Xu Y, Leysath CE, et al. (2008) CXCR4 up-regulation by imatinib induces chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) cell migration to bone marrow stroma and promotes survival of quiescent CML cells. Mol Cancer Ther 7: 48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zeng Z, Samudio IJ, Munsell M, An J, Huang Z, et al. (2006) Inhibition of CXCR4 with the novel RCP168 peptide overcomes stroma-mediated chemoresistance in chronic and acute leukemias. Mol Cancer Ther 5: 3113–3121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]