Abstract

Background/Aims

Several rescue therapies have been recommended to eradicate Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with a failure of first-line eradication therapy, but they still fail in more than 20% of cases. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of levofloxacin, metronidazole, and lansoprazole (LML) triple therapy relative to quadruple therapy as a second-line treatment.

Methods

In total, 113 patients who failed first-line triple therapy for H. pylori infection were randomly assigned to two groups: LML for 7 days and tetracycline, bismuth subcitrate, metronidazole and lansoprazole (quadruple) for 7 days.

Results

According to intention-to-treat analysis, the infection was eradicated in 38 of 56 patients (67.9%) in the LML group and 48 of 57 (84.2%) in the quadruple group (p=0.042). Per-protocol analysis showed successful eradication in 38 of 52 patients (73.1%) from the LML group and 48 of 52 (92.3%) from the quadruple group (p=0.010). There were no significant differences in the adverse effects in either treatment group.

Conclusions

LML therapy is less effective than quadruple therapy as a second-line treatment for H. pylori infection. Therefore, quadruple therapy should be considered as the primary second-line strategy for patients experiencing a failure of first-line H. pylori therapy in Korea.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Therapeutics, Failure, Levofloxacin, Metronidazole

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori infection is recognized as an important contributor to nonulcer dyspepsia, peptic ulcer disease, gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric cancer. Eradication of H. pylori significantly reduces the relapse rate of peptic ulcer disease.1,2 A triple therapy, comprising amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), is the first-line treatment suggested by international guidelines.3-5 However, several large clinical trials have shown that this standard triple therapy for 7 to 14 days fails to eradicate H. pylori infection in up to 20% to 25% of patients.6,7

Many factors, including lack of compliance, age, sex, smoking, and concurrent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use can effect treatment failure.8 However, antibiotic resistance has been identified as a major factor affecting cure of H. pylori infections, and the antibiotic resistance rate has been increasing in many areas, including Korea.8-10 Several consensus meeting reports (including the Asia-Pacific Consensus Conference11 and the Maastricht III Consensus Report4) recommend the use of quadruple therapy for 1 or 2 weeks as a second-line therapy. However, this quadruple therapy requires the administration of four drugs with a complex regimen (bismuth and tetracycline are usually prescribed every 6 hours) and is associated with relatively high incidence of adverse effects.12 Furthermore, this quadruple regimen still fails to eradicate H. pylori in approximately 20% to 30% of patients.12,13

Recently, it has been suggested that a levofloxacin-based rescue therapy constitutes an encouraging second-line strategy, representing an alternative to quadruple therapy in patients with previous amoxicillin-clarithromycin-PPI failure, with the added advantages of efficacy, simplicity, and safety.14-16 The satisfactory eradication rate of levofloxacin-based triple therapy has been confirmed by an open-labeled study in the United States.17 However, most studies pertaining to levofloxacin-based therapy used a combination with amoxicillin.18-20 To our knowledge, the combination of levofloxacin and metronidazole as a second-line treatment has not been reported before. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a triple therapy containing levofloxacin and metronidazole in comparison to quadruple therapy as a second-line treatment of H. pylori infections.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

This open, randomized, prospective study was performed at two medical centers (Pusan National University Hospital and Good Samsun Hospital, Busan, Korea). The study population consisted of 113 patients in whom a first-line triple therapy (amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and lansoprazole) for 7 days had failed between January 2008 and December 2010. In all patients, H. pylori eradication failure was confirmed by a positive 13C-urea breath test. Exclusion criteria were 1) age below 18 years, 2) severe cardiopulmonary, liver or renal disease, 3) known drug allergy to study drugs, 4) pregnancy and lactation, or 5) previous gastric surgery.

This study was performed in accordance with good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki Guidelines. The Institutional Review Board of the Pusan National University Hospital approved this study, and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

2. Therapy

Patients who failed first-line triple therapy were randomized to undergo one of the following treatments: 1) levofloxacin (500 mg) once, metronidazole (500 mg) three times, and lansoprazole (30 mg) twice daily for 7 days (levofloxacin, metronidazole, and lansoprazole [LML] therapy), or 2) tetracycline (500 mg) four times, bismuth subcitrate (120 mg) four times, metronidazole (500 mg) three times, and lansoprazole (30 mg) twice daily for 7 days (quadruple therapy).

H. pylori eradication was defined as a negative 13C-urea breath test performed 8 weeks after completion of treatment. The patients were interviewed during their first visit to the clinic after completion of therapy in order to evaluate their compliance with the therapy and any adverse effects. Poor compliance was defined as taking less than 80% of the medication prescribed.

3. Statistical analysis

On the basis of previous data in Korea,13 the H. pylori eradication rate following quadruple therapy was expected to be 70%. To detect a 25% difference in efficacy of the tested regimen with a power of 80% and an α-error of 5%, at least 43 patients per group were required. Considering a dropout rate of 20%, the final required sample size was calculated to be 52 patients per group. Categorical variables were compared with the chi-square tests, and quantitative variables with Student t-test. The primary outcome was eradication of H. pylori infection. Analysis of H. pylori eradication efficacy was performed on an "intention-to-treat (ITT)" basis (including all eligible patients enrolled into the study, regardless of compliance with the study protocol; patients with unevaluable data were assumed to have been unsuccessfully treated) and on a "per-protocol (PP)" basis (excluding patients with poor therapy compliance, and those with unevaluable data after therapy). A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical calculations were performed using SPSS version 12.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

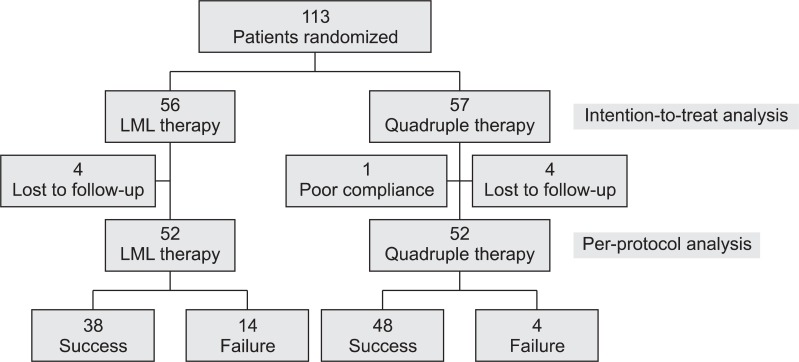

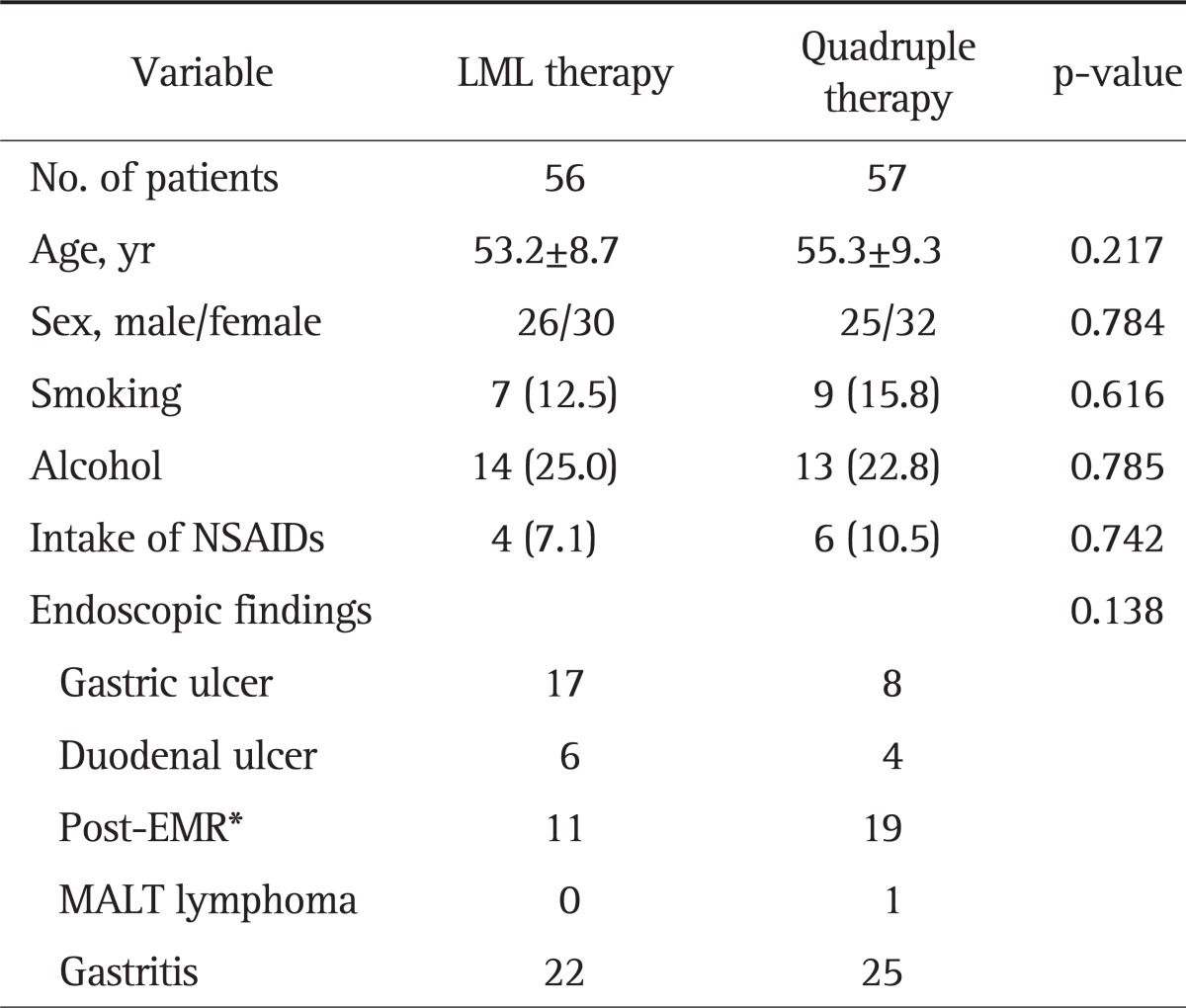

One hundred and thirteen patients (51 men, aged 26 to 74 years) were included in this study. Patient demographic and clinical data, at the time of study entry, are summarized in Table 1. Of the 113 patients, 56 were enrolled in the LML group and 57 in the quadruple group. Overall, 104 patients (92%) completed the study's therapeutic regimen. One patient in the quadruple group dropped out due to noncompliance for personal reasons. An additional four patients from each group did not appear at the first visit after completion of therapy and were lost to follow-up (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Who Were Randomly Assigned to Levofloxacin, Metronidazole, and Lansoprazole Therapy or Quadruple Therapy

Data are presented as mean±SD or number (%).

LML, levofloxacin, metronidazole, and lansoprazole; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; MALT, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

*Patients who had received endoscopic treatment for early gastric cancer or adenoma.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diaphragm of the subjects' progress through the phases of the study.

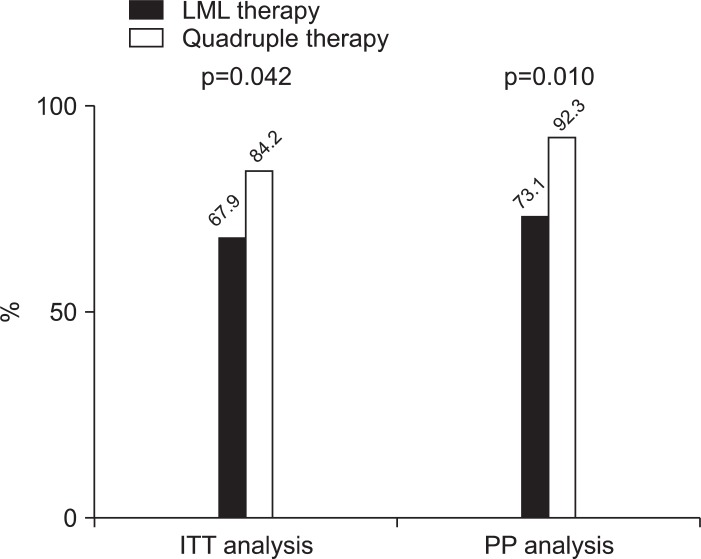

After the completion of therapy, 86 of 104 patients (82.7%) tested negative for H. pylori by the 13C-urea breath test. According to ITT analysis, the infection was eradicated in 38 of 56 patients (67.9%) from the LML group and in 48 of 57 (84.2%) from the quadruple group (p=0.042) (Fig. 2). PP analysis showed successful eradication in 38 of 52 patients (73.1%) from the LML group and in 48 of 52 (92.3%) from the quadruple group (p=0.010).

Fig. 2.

Intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analysis of Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients randomly assigned to levofloxacin, metronidazole, and lansoprazole (LML) therapy or quadruple therapy.

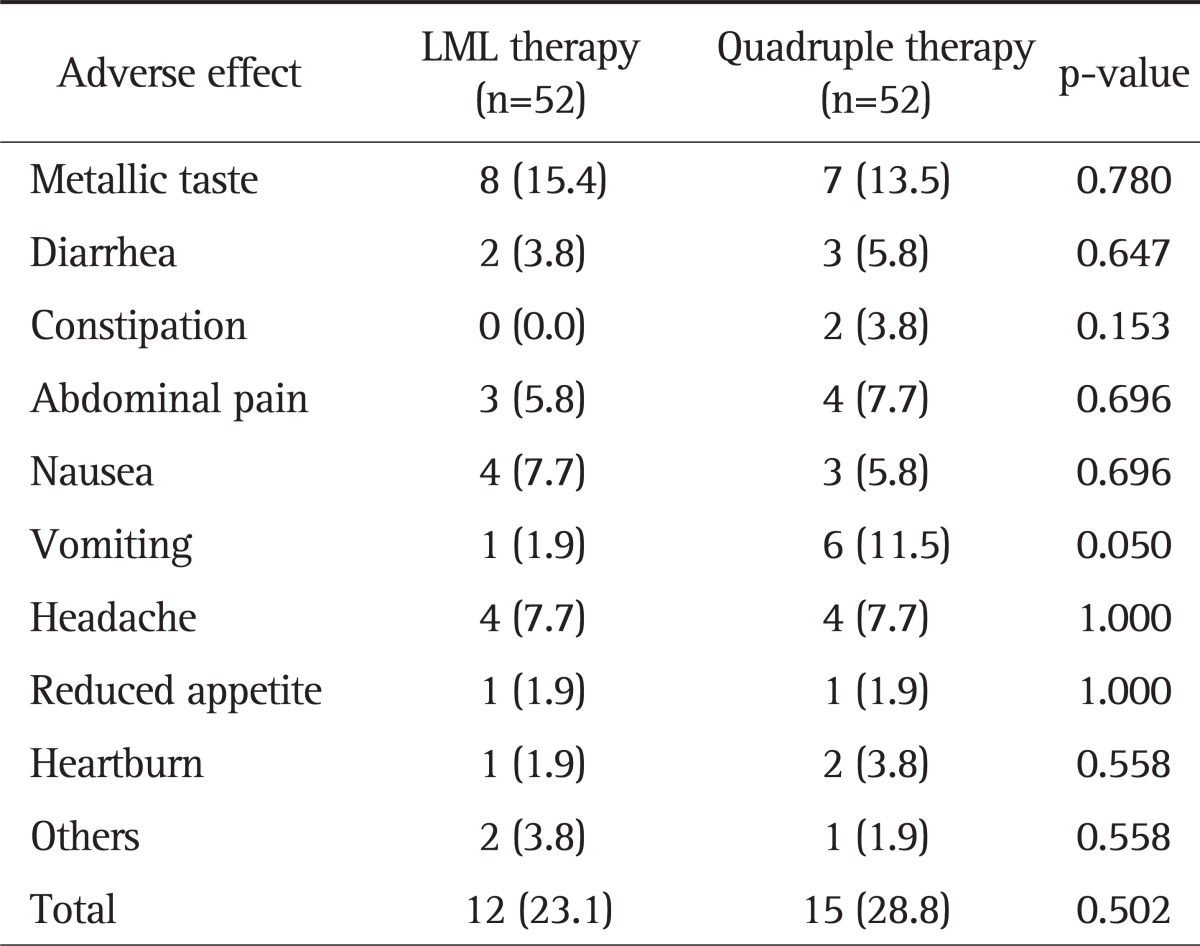

There were no significant differences in the adverse effects experienced by the patients in either treatment group (Table 2); 12 of 52 patients (23.1%) in the LML group and 15 of 52 patients (28.8%) in the quadruple group reported adverse events (p=0.502). A metallic taste was the most common adverse effect reported by patients from both groups. More patients in the quadruple group complained of vomiting than those in the LML group. All adverse effects were self-limiting and disappeared once therapy was terminated.

Table 2.

Patients with Self-Reported Adverse Effects during Levofloxacin, Metronidazole, and Lansoprazole Therapy and Quadruple Therapy

Data are presented as number (%).

LML, levofloxacin, metronidazole, and lansoprazole.

DISCUSSION

This study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of LML therapy, compared to quadruple therapy, as a second-line treatment for H. pylori infections. The H. pylori eradication rate for the LML therapy was 67.9% and 73.1% in the ITT and PP analyses, respectively. This regimen was well tolerated, and compliance was good. Although the eradication rate of LML therapy was not particularly low, it was lower than that of the quadruple therapy (84.2% and 92.3% in the ITT and PP analyses, respectively).

Levofloxacin-based therapies represent an encouraging strategy for cases of H. pylori eradication failure. In one study involving a 10-day treatment regimen consisting of amoxicillin, levofloxacin, and PPI in patients following standard triple therapy failure, the eradication rate was 85%.21 Other studies have also shown exciting results with eradication rates in excess of 75%.22,23 In a study conducted in Italy involving 280 patients who failed to respond to standard triple therapy, the eradication rate of the patients treated with levofloxacin and tinidazole (90%) was higher than that of those treated with the standard quadruple therapy (63%), and the side effects were less frequent in the levofloxacin and tinidazole group than in the quadruple group.24

Most previous studies have used amoxicillin in combination with a quinolone as a second-line regimen. However, in this study, we chose metronidazole instead of amoxicillin for two reasons. First, because pretreatment antibiotic resistance is an important factor for treatment failure, it would be reasonable not to choose the same antibiotics used in the failed first-line treatment. Even though it is generally known that the resistance rate of H. pylori to amoxicillin is low, the amoxicillin resistance rate is increasing in Korea (9.1% to 13.8%).25,26 Second, metronidazole remains a major drug for eradication therapy, despite a relatively high resistance rate. Although metronidazole resistance can affect the successful eradication of H. pylori in metronidazole-containing salvage therapy, some studies have shown that metronidazole resistance is not a major determinant of the failure rate.15,24 Moreover, Gerrits et al.27 reported that metronidazole-resistant H. pylori isolates can reduce the efficacy of metronidazole containing regimens, but does not make them completely ineffective. This discrepancy between in vitro metronidazole resistance and treatment outcome may be partially explained by changes in the oxygen pressure in the gastric environment, as metronidazole-resistant H. pylori isolates can become metronidazole susceptible under low oxygen conditions in vitro. These combined results suggested that the LML therapy used in the present study could overcome metronidazole resistance to some degree.

Generally, resistance to quinolones is easily acquired and, in countries with a high consumption of these drugs (like Korea), the resistance rate is increasing particularly rapidly.14 For example, in Korea, the resistance rate to quinolones was approximately 5% in 2003;25 it increased to 23.2% to 25.7% in only 5 to 7 years.26,28 Similar to metronidazole, the success rate of levofloxacin-based second-line therapies is affected by the levofloxacin resistance rate.1 Some studies have shown a marked decrease in the effectiveness of the quinolone-based regimen, which is further supported by the recent bacterial culture data.21,23 Even though a sensitivity test was not conducted in this study to determine the frequency and extent of H. pylori quinolone resistance, the higher quinolone resistance rate in Korea could explain the lower eradication rate achieved with LML therapy in this study.

The H. pylori eradication rate of the quadruple therapy, in this study, was relatively high compared to other studies. The eradication rate of 7-day quadruple therapy in Korea is reported to be 63% to 81%,13 but, in the present study, the eradication rate was 92.3% by PP analysis. This high eradication rate of quadruple therapy might accentuate the difference in eradication rates between the two groups.

Our study has some limitations. First, we did not examine the antibiotic sensitivity of patient H. pylori strains, precluding the analysis of the eradication rate according to the sensitivity of the bacteria to each antibiotic. Second, the duration of the LML therapy was only 7 days. Other studies have shown better results following more than 10 days of eradication therapy, rather than 7 days.22,24,29 This suggests that the outcome of the present study may have been different if the LML therapy had been conducted for 10 to 14 days.

In conclusion, 7-day LML therapy as a second-line treatment for H. pylori infection is safe but less effective than the standard quadruple therapy. Although further studies based on the antibiotic susceptibility tests are needed, the results of the present study indicate that quadruple therapy would be considered as the primary second-line strategy for patients experiencing first-line H. pylori therapy failure in Korea.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry for Health, Welfare and Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (0920050) and by a clinical research grant from Pusan National University Hospital 2012.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Wong WM, Gu Q, Chu KM, et al. Lansoprazole, levofloxacin and amoxicillin triple therapy vs. quadruple therapy as second-line treatment of resistant Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:421–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopkins RJ, Girardi LS, Turney EA. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori eradication and reduced duodenal and gastric ulcer recurrence: a review. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1244–1252. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zullo A, De Francesco V, Manes G, Scaccianoce G, Cristofari F, Hassan C. Second-line and rescue therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication in clinical practice. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:131–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain C, et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772–781. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.101634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fock KM, Katelaris P, Sugano K, et al. Second Asia-Pacific Consensus Guidelines for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1587–1600. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gisbert JP, González L, Calvet X, et al. Proton pump inhibitor, clarithromycin and either amoxycillin or nitroimidazole: a meta-analysis of eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1319–1328. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2000.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuccio L, Minardi ME, Zagari RM, Grilli D, Magrini N, Bazzoli F. Meta-analysis: duration of first-line proton-pump inhibitor based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:553–562. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee JH, Hong SP, Kwon CI, et al. The efficacy of levofloxacin based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;48:19–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lamouliatte H, Samoyeau R, De Mascarel A, Megraud F. Double vs. single dose of pantoprazole in combination with clarithromycin and amoxycillin for 7 days, in eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with non-ulcer dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1523–1530. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wurzer H, Rodrigo L, Stamler D, et al. ACT-10 Study Group. Short-course therapy with amoxycillin-clarithromycin triple therapy for 10 days (ACT-10) eradicates Helicobacter pylori and heals duodenal ulcer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1997;11:943–952. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam SK, Talley NJ. Report of the 1997 Asia Pacific Consensus Conference on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gisbert JP, Pajares JM. Review article: Helicobacter pylori "rescue" regimen when proton pump inhibitor-based triple therapies fail. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1047–1057. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SY, Jung SW. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;58:67–73. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2011.58.2.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gisbert JP. Second-line rescue therapy of helicobacter pylori infection. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2009;2:331–356. doi: 10.1177/1756283X09347109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y, Huang X, Yao L, Shi R, Zhang G. Advantages of Moxifloxacin and Levofloxacin-based triple therapy for second-line treatments of persistent Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta analysis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2010;122:413–422. doi: 10.1007/s00508-010-1404-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watanabe Y, Aoyama N, Shirasaka D, et al. Levofloxacin based triple therapy as a second-line treatment after failure of helicobacter pylori eradication with standard triple therapy. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:711–715. doi: 10.1016/s1590-8658(03)00432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Caro S, Zocco MA, Cremonini F, et al. Levofloxacin based regimens for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:1309–1312. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200212000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gisbert JP, Gisbert JL, Marcos S, Jimenez-Alonso I, Moreno-Otero R, Pajares JM. Empirical rescue therapy after Helicobacter pylori treatment failure: a 10-year single-centre study of 500 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:346–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bilardi C, Dulbecco P, Zentilin P, et al. A 10-day levofloxacin-based therapy in patients with resistant Helicobacter pylori infection: a controlled trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:997–1002. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00458-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto Y, Miki I, Aoyama N, et al. Levofloxacin- versus metronidazole-based rescue therapy for H. pylori infection in Japan. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:821–825. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Di Caro S, Franceschi F, Mariani A, et al. Second-line levofloxacin-based triple schemes for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:480–485. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gisbert JP, Morena F. Systematic review and meta-analysis: levofloxacin-based rescue regimens after Helicobacter pylori treatment failure. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo CH, Hu HM, Kuo FC, et al. Efficacy of levofloxacin-based rescue therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection after standard triple therapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:1017–1024. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nista EC, Candelli M, Cremonini F, et al. Levofloxacin-based triple therapy vs. quadruple therapy in second-line Helicobacter pylori treatment: a randomized trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:627–633. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim N, Kim JM, Kim CH, et al. Institutional difference of antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori strains in Korea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:683–687. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200609000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JY, Kim NY, Kim SJ, et al. Regional difference of antibiotic resistance of helicobacter pylori strains in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;57:221–229. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2011.57.4.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gerrits MM, van der Wouden EJ, Bax DA, et al. Role of the rdxA and frxA genes in oxygen-dependent metronidazole resistance of Helicobacter pylori. J Med Microbiol. 2004;53(Pt 11):1123–1128. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45701-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JY, Kim N, Park HK, et al. Primary antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori strains and eradication rate according to gastroduodenal disease in Korea. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011;58:74–81. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2011.58.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saad RJ, Schoenfeld P, Kim HM, Chey WD. Levofloxacin-based triple therapy versus bismuth-based quadruple therapy for persistent Helicobacter pyori infection: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:488–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00637.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]