Abstract

Background/Aims

The use of self-expandable metallic stents (SEMS) is an established palliative treatment for malignant stenosis in the gastrointestinal tract; therefore, its application to benign stenosis is expected to be beneficial because of the more gradual and sustained dilatation in the stenotic portion. We aimed in this prospective observational study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of temporary SEMS placement in benign pyloric stenosis.

Methods

Twenty-two patients with benign stenosis of the prepylorus, pylorus, and duodenal bulb were enrolled and underwent SEMS placement. We assessed symptom improvement, defined as an increase of at least 1 degree in the gastric-outlet-obstruction scoring system after stent insertion.

Results

No major complications were observed during the procedures. After stent placement, early symptom improvement was achieved in 18 of 22 patients (81.8%). During the follow-up period (mean 10.2 months), the stents remained in place successfully for 6 to 8 weeks in seven patients (31.8%). Among the 15 patients (62.5%) with stent migration, seven (46.6%) showed continued symptomatic improvement without recurrence of obstructive symptoms.

Conclusions

Despite the symptomatic improvement, temporary SEMS placement is premature as an effective therapeutic tool for benign pyloric stenosis unless a novel stent is developed to prevent migration.

Keywords: Benign pyloric stenosis, Self-expandable metallic stent

INTRODUCTION

Benign stricture of the alimentary tract is caused by peptic ulcer, postsurgical healing of an anastomosis, or ingestion of corrosive agents, and involves various sites including the esophagus, pylorus, duodenum, and colon. Pyloric stenosis due to benign causes has been treated with endoscopic balloon dilatation as an alternative to surgery.1-4 However, although its short-term clinical outcome is favorable, the long-term results are often disappointing, with 51% of patients requiring subsequent surgery, 33% experiencing recurrent obstructions, and there is an associated risk of bleeding or perforation.2-4

The use of self-expandable metallic stents (SEMS) is an established palliative treatment to relieve the obstructive symptoms of inoperable gastrointestinal (GI) tract malignancy with stenotic change. Newly-developed SEMS that are flexible and can maintain patency on a severely curved pylorus or duodenal bulb, combined with use of a delivery system for through-the-scope (TTS) placement with a large working channel, enable endoscopists to insert stents under the inspection of targeted sites.5-10 Obstruction of the stomach or duodenum may cause nausea, vomiting, or cachexia, which can lead to malnutrition and clinical deterioration.11 SEMS have some benefits over gastrostomy including a higher convenience for use and fewer complications, and can be considered as the first option for palliative treatment of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction in patients with poor performance status and life expectancies of less than 6 months.7,12

Given this background, SEMS application in benign stenosis can be expected to be beneficial due to more gradual and sustained dilatation in the stenotic portion, no need to repeat procedures, and fewer major complications other than stent migration. However, there have been a few small studies and case experiences on the treatment of benign pyloric stricture by temporary placement of endoscopic stent.13,14 Therefore, in this study we evaluated the efficacy and safety of temporary SEMS placement in benign pyloric stenosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients

From May 2003 to March 2012, 22 patients with benign stenosis of the prepylorus, pylorus, and duodenal bulb, or of an anastomosis site were enrolled and underwent SEMS insertion. All of the enrolled patients met the following criteria: 1) had suffered from obstructive symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal bloating, and pain that were not improved after conservative treatment; 2) showed succussion splash; and 3) had findings of pyloric stenosis on upper GI imaging after oral contrast opacification through which an endoscopic tip could not be passed. All of the patients received upper GI imaging after oral contrast, and the degree and site of stenosis were evaluated before the endoscopic procedure. We excluded patients if they had only mild obstructive symptoms and the endoscope could pass through the stenosis, or if there was evidence of multiple strictures or obstructions. Informed consent was obtained from each patient and the study was a designed as prospective observational series. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Korea University Guro Hospital.

2. Equipment

We used covered pyloric SEMS that were 18 or 20 mm in diameter and 70, 80, 90, or 100 mm in length. The stent was tightly mounted on a delivery system with an outer diameter of 10 to 11 Fr and overall length of 180 cm. We deployed the stent by inserting the delivery system through the working channel of the endoscope. We used a forward-viewing endoscope with a working channel of 3.7 mm (GIF-2T 240; Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan), and a standard 5 Fr biliary catheter and a flexible 0.035 inch biliary guidewire (MET-II-35; Wilson-Cook, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) to guide and negotiate through the stenosis.

3. Endoscopic technique

All procedures were performed under endoscopic and fluoroscopic guidance. After identification of the stenosis, a standard biliary catheter was passed through the working channel, following a biliary guidewire. When the catheter was then passed through the stenosis, a water soluble contrast liquid was injected and the distal end of the stenosis was monitored under fluoroscopic control. The length of the stenosis was estimated by the distance the catheter traveled over the guidewire. After this, a stiff guidewire (Jagwire™; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) was inserted through the catheter, which was then able to be removed.

We selected a covered stent that had 1 to 2 cm of free margin proximal and distal to the stenosis. An undeployed SEMS delivery system was inserted through the working channel of the endoscope over the guidewire, and the stent was slowly deployed from the distal to the proximal end. Repositioning of the proximal end of the stent was performed as needed. After placement of the stent, the stiff guidewire and endoscope were withdrawn and the position of stent was confirmed by abdominal plain radiography.

4. Assessment of clinical outcomes and follow-ups

We evaluated the clinical outcomes such as symptomatic improvement, recurrence of obstructive symptoms, and stenosis after SEMS insertion. Degree of obstructive symptoms before and after SEMS application was assessed using gastric outlet obstruction scoring system (GOOSS),15 as 4-point scale: 0, no oral intake; 1, liquids only; 2, soft solids only; 3, low reside or full diet. GOOSS was assessed before and 3 days after the procedure. Follow-up endoscopy was performed 24 hours after the procedure to evaluate the position and patency of the stent and to identify any early complications. After the initial follow-up, oral intake was permitted beginning with liquids and progressing to a soft diet if there was no major complication. Further follow-up endoscopic examinations were performed 1, 2, 4, and 6 weeks after SEMS application. If symptoms had improved and the previously inserted SEMS was in place, 6 to 8 weeks into the follow-up period, the SEMS was removed through an endoscopic procedure using a polypectomy snare or a rat tooth. After elective removal of SEMS, patients were given upper GI endoscopy at 3- to 6-month intervals or when obstructive symptoms recurred. If migration of the SEMS occurred, patients were subdivided into early migration (migration within 8 days of the procedure) and late migration (migration after the 8th day) groups and their clinical courses were compared.

RESULTS

1. Baseline characteristics of patients

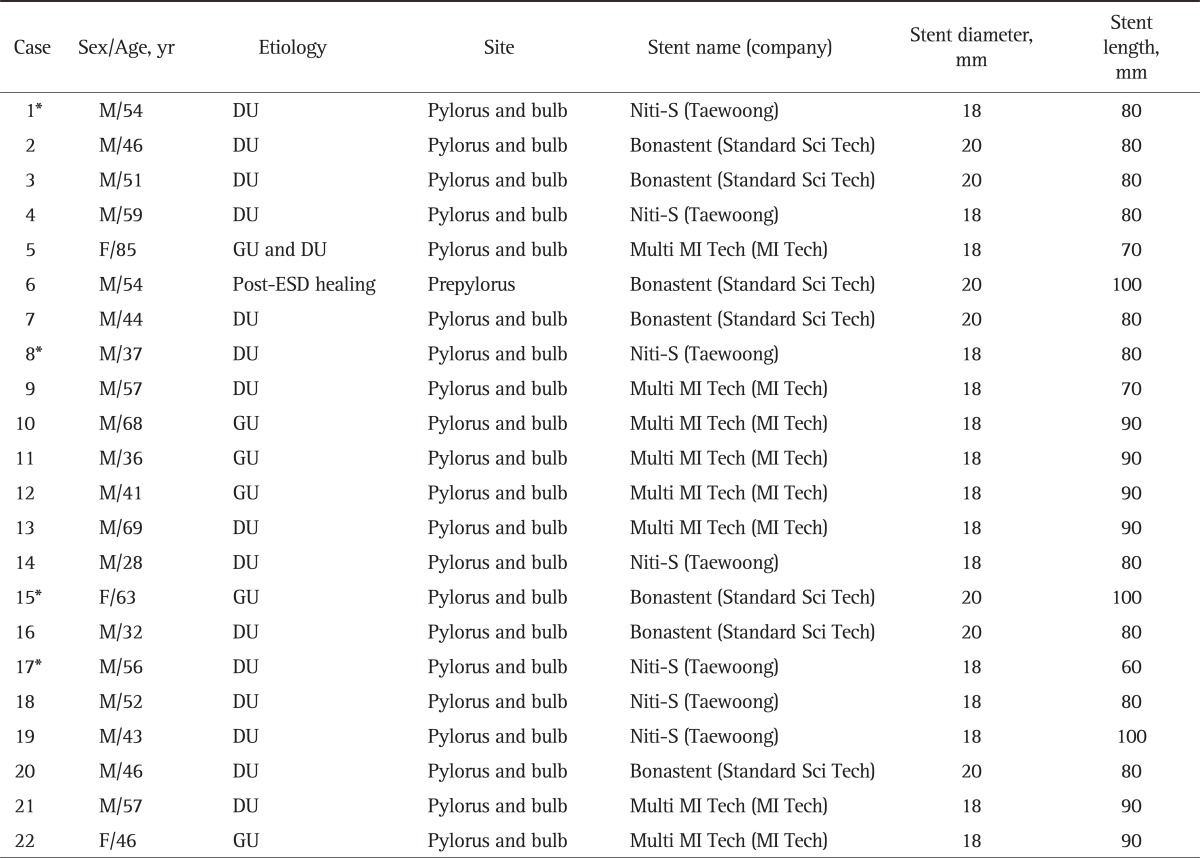

Of the 22 patients, 19 were male and three were female, with a mean age of 51.1 years (range, 28 to 85 years). The causes of benign stenosis were duodenal ulcer in 15 patients (68.2%), gastric ulcer in five patients, both gastric and duodenal ulcers in one patient, and prepyloric stenosis after endoscopic submucosal dissection in one patient. Four of them underwent endoscopic balloon dilation therapy prior to SEMS insertion (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of the Patients Who Underwent Self-Expandable Metallic Stent Insertion because of Benign Pyloric Stenosis

M, male; DU, duodenal ulcer; F, female; GU, gastric ulcer; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection.

*Prior endoscopic balloon dilation therapy.

2. Clinical outcomes and complications

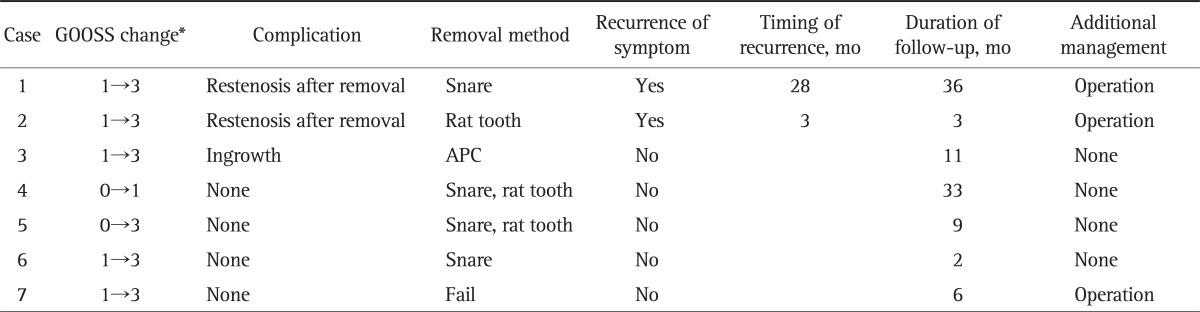

During the SEMS insertion procedure there were no major complications such as serious bleeding or bowel perforation or procedure-related mortality. After SEMS placement, early symptomatic improvement, defined as an increase of GOOSS by at least 1 degree within 3 days of the procedure,6 was achieved in 18 of 22 patients (81.8%) whereas no improvement was noted in four patients. Regarding the degree of GOOSS, five patients with GOOSS 1 and one patient with score 0 were improved to 3 after the procedure, which meant that the patients could digest solid meals. Eleven patients of score 1 were increased to 2 and one patient of 0 was increased to 1 (Tables 2 and 3). Among the 18 patients whose symptoms improved early after SEMS insertion and who were followed for more than 6 weeks, 12 (66.7%) were maintained without recurrence of obstructive symptoms, while six (33.3%) suffered from symptom recurrence.

Table 2.

Clinical Outcomes and Complications after Placement of the Self-Expandable Metallic Stent in the Nonmigration Group

GOOSS, gastric outlet obstruction scoring system; APC, argon plasma coagulation.

*Assessed by GOOSS: 0, no oral intake; 1, liquids only; 2, soft solids only; 3, low reside or full diet.

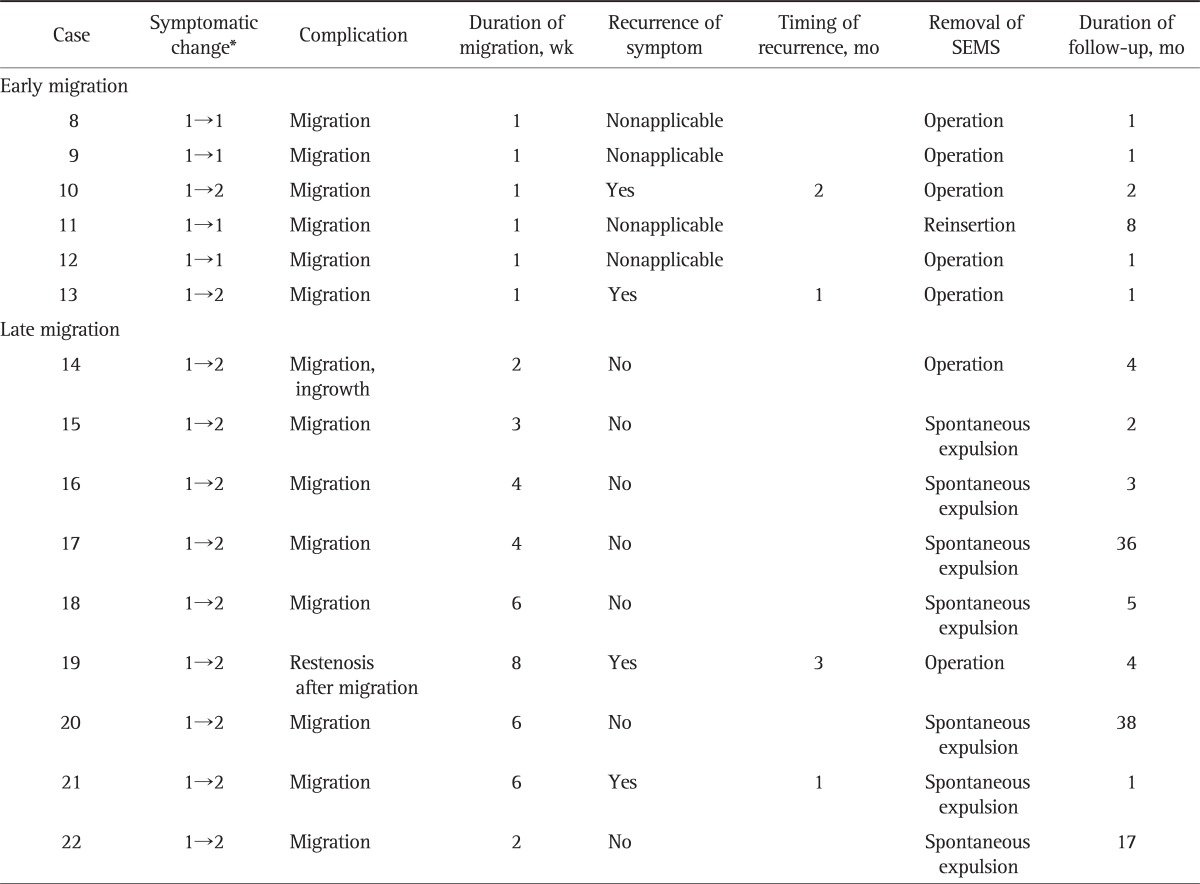

Table 3.

Clinical Outcomes and Complications after Placement of the Self-Expandable Metallic Stent in the Migration Group

SEMS, self-expandable metallic stent.

*Assessed by gastric outlet obstruction scoring system (GOOSS): 0, no oral intake; 1, liquids only; 2, soft solids only; 3, low reside or full diet.

Complications after intervention were evaluated during the endoscopic follow-ups. Migration of the SEMS was observed in 15 of 22 patients (68.2%), and among them, six cases occurred within 1 week, two within 2 weeks, three between 3 and 4 weeks, and four between 6 and 8 weeks of the procedure. Therefore, early migration occurred in six of 15 patients and nine cases were corresponding to late migration. Five patients with early migration suffered from continuation or recurrence of obstructive symptoms and received bypass surgery with concomitant removal of the SEMS and one patient reinserted the SEMS. In seven of nine patients with late migration, SEMS was unable to retrieve endoscopically because they had already passed through beyond the reach of endoscopy; however, they were expelled outside of the GI tract naturally without symptomatic occurrence. One patient did not suffer recurrent obstructive symptoms, but he underwent surgery because the SEMS could not be removed endoscopically or spontaneously, and another one patient underwent surgery due to symptomatic recurrence after migration. In brief, seven of 15 patients (46.7%) were maintained without symptomatic recurrence despite migration of the SEMS, and all six patients with early migration suffered continued or recurrent symptoms. However, seven of nine patients (77.7%) with late migration did not suffer recurrent obstructive symptoms (Table 3).

The major complication of stent ingrowth or overgrowth occurred in two patients in our study; however, they did not experience symptomatic recurrence. Restenosis of the pylorus developed in three patients: one case occurred after migration and the other two after elective removal of the SEMS; all three patients underwent surgery due to recurrent obstructive symptoms.

3. Removal of SEMS

During the follow-up period (range, 1 to 38 months; median, 10.2 months), SEMS remained in place for 6 to 8 weeks in seven of 22 patients (31.8%). Among these patients, six underwent successful elective removal of the SEMS via the endoscopic approach using a polypectomy snare or rat tooth, and one patient was operated on due to a failed endoscopic removal. In one patient who underwent endoscopic removal, the SEMS was impacted within the proximal or distal end of the overriding mucosa and was removed successfully using argon plasma coagulation (APC). Of the six patients who underwent endoscopic removal of the SEMS, restenosis of the pylorus occurred in two patients, who both received additional surgeries, whereas the other four patients were well managed without obstructive symptoms or pyloric restenosis through more than 2 months of follow-up (Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Palliative use of SEMS has been established as a standard treatment for GI tract malignancy, and there are a large number of data describing its palliative use and clinical outcome. However, the application of SEMS in benign stenosis has rarely been reported. Several reports have suggested temporary use of SEMS in benign stenosis of the GI tract,16,17 although the majority of the data is limited to esophageal lesions including an anastomosis site stricture or achalasia.18,19 According to previous studies, temporary placement of SEMS in benign esophageal stenosis improved dysphagia symptoms in the majority of patients and reduced the frequency of symptom recurrence to approximately 10% to 20% of patients. However, despite this improvement, 40% to 50% of patients showed delayed complications involving new strictures or stent migrations; this result warrants further investigation into the temporary placement of a retrievable covered stent in certain cases.18,19 Furthermore, there have been several reports concerning the temporary implantation of SEMS in benign colonic strictures with near total or total obstruction caused by diverticular/inflammatory disease, postsurgical anastomosis, radiation, or Crohn disease. In such cases, SEMS could offer medium-term symptom relief and might effectively decompress the high-grade benign colonic obstruction, thereby allowing for elective surgery.20,21 Recently, several studies reported the use of SEMS in benign pyloric stenosis; however, the majority included small numbers of benign pyloric stenosis and large numbers of other GI tract lesions or malignant pyloric/duodenal strictures.8,13,18,22

This clinical study evaluated the effects of a temporary insertion of SEMS for benign pyloric stenosis only. Immediate symptomatic improvement within 3 days of the procedure was achieved in 18 of the 22 enrolled patients (81.8%), and the majority of these could ingest solid foods comfortably. In 12 of 18 patients (66.7%), this clinical effect continued for 6 to 8 weeks and was well maintained without symptomatic recurrence during the 6 months of follow-up. Moreover, the technical success rate of 100% indicated that it may be possible to use TTS, which enables endoscopists to inspect the stenotic lesion via endoscopy and place SEMS at the targeted position. TTS has some additional advantages, such as convenience for clinicians and reduced discomfort and higher compliance for patients.

Considering major complications after the procedure, migration of the SEMS was the most common complication. We used covered SEMS to allow for elective removal at regular intervals, which may have contributed to the higher rate of migration. In our study, 15 of 22 patients (68.2%) experienced migration of the SEMS, and this occurred within 2 weeks in eight patients (53.3%) and between 3 and 8 weeks in seven patients (46.7%). These results are compatible with other studies of SEMS in benign esophageal stricture, which reported migration as one of the most common complications, with the majority of migrations occurring within 1 to 8 weeks.18,19 From a different perspective, in our study, all five patients were without symptomatic recurrence despite migration of the SEMS between 2 to 4 weeks, whereas, two of four patients were maintained between 5 to 8 weeks. Thus, it would be considerable to remove the stent 4 weeks after stent insertion. Or possibly, placement of clip on the upper edge of the stent would also be helpful to prevent migration. A recent observational study demonstrated that anchoring the fully covered SEMS with the endoscopic clip is feasible and significantly reduces esophageal stent migration.23 Although this mentioned study is a positive study about clipping of SEMS, still there are few studies mentioning about antral stenting and because of the peristalsis of the stomach, the clinical condition of the esophagus and stomach might be different.

Interestingly, symptomatic improvement continued in seven of 15 patients (46.7%) who experienced SEMS migration, and the majority of them corresponded to late migration. This suggests that at least 1 week of SEMS placement may guarantee gradual dilatation of the stenotic portion and an appropriate therapeutic effect despite subsequent migration. The migrated SEMS was eliminated spontaneously without major complications such as perforation or obstruction in six of the seven patients who had continued clinical benefit. However, in the best scenario, the implanted SEMS should remain in place for 6 to 8 weeks until the elective removal with an endoscopic procedure, which could be performed using a snare, rat tooth, or even APC in the case of ingrowth within the SEMS. It seems to bear some risks of operation for removal of migrated SEMS, especially in case of early migration.

For optimal application of SEMS, partially covered or completely covered (including the outer layer) SEMS should be used for benign GI stricture. Cwikiel et al.24 reported an experimental study of SEMS in the treatment of benign esophageal strictures in pigs. In this study, granulation tissue grew and merged with the uncovered area of SEMS after 1 week, resulting in difficulties in removal. Another serious problem is that bile or gastric acid may dissolve the membrane of the SEMS leading to ingrowth. It is therefore necessary to develop a novel SEMS with reduced migration and increased durability. To prevent long-term complications, newly developed biodegradable SEMS have been tested for the treatment of benign esophageal stricture,25,26 and clinical outcomes of large scale studies should be accumulated to apply these findings to benign pyloric stenosis.

In conclusion, temporary SEMS placement in benign pyloric stenosis had some effects on symptom improvement and gradual repeated dilation for stenotic lesions; however, it seems premature to consider it as an alternative therapeutic tool for surgery or endoscopic balloon dilation due to its frequent migration. To overcome major complications such as migration or stent ingrowth, it is necessary to develop novel SEMS and perform more clinical studies to assess the optimal timing for the placement of SEMS and the selection of patients. Ultimately, a randomized controlled trial should be performed to compare and evaluate the clinical benefits of temporary SEMS placement with other treatment modalities for benign pyloric stenosis.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Griffin SM, Chung SC, Leung JW, Li AK. Peptic pyloric stenosis treated by endoscopic balloon dilatation. Br J Surg. 1989;76:1147–1148. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800761112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lau JY, Chung SC, Sung JJ, et al. Through-the-scope balloon dilation for pyloric stenosis: long-term results. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43(2 Pt 1):98–101. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(06)80107-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Misra SP, Dwivedi M. Long-term follow-up of patients undergoing ballon dilation for benign pyloric stenoses. Endoscopy. 1996;28:552–554. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1005553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solt J, Bajor J, Szabó M, Horváth OP. Long-term results of balloon catheter dilation for benign gastric outlet stenosis. Endoscopy. 2003;35:490–495. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-39664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiori E, Lamazza A, Volpino P, et al. Palliative management of malignant antro-pyloric strictures. Gastroenterostomy vs. endoscopic stenting. A randomized prospective trial. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:269–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JH, Song HY, Shin JH, et al. Metallic stent placement in the palliative treatment of malignant gastroduodenal obstructions: prospective evaluation of results and factors influencing outcome in 213 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:256–264. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittal A, Windsor J, Woodfield J, Casey P, Lane M. Matched study of three methods for palliation of malignant pyloroduodenal obstruction. Br J Surg. 2004;91:205–209. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Profili S, Meloni GB, Bifulco V, Conti M, Feo CF, Canalis GC. Self-expandable metal stents in the treatment of antro-pyloric and/or duodenal strictures. Acta Radiol. 2001;42:176–180. doi: 10.1080/028418501127346477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stawowy M, Kruse A, Mortensen FV, Funch-Jensen P. Endoscopic stenting for malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:5–9. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e31803125b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uno Y, Obara K, Kanazawa K, Sasaki Y, Fukuda S, Munakata A. Stent implantation for malignant pyloric stenosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:552–555. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bessoud B, de Baere T, Denys A, et al. Malignant gastroduodenal obstruction: palliation with self-expanding metallic stents. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16(2 Pt 1):247–253. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000145227.90754.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeurnink SM, van Eijck CH, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. Stent versus gastrojejunostomy for the palliation of gastric outlet obstruction: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dormann AJ, Deppe H, Wigginghaus B. Self-expanding metallic stents for continuous dilatation of benign stenoses in gastrointestinal tract: first results of long-term follow-up in interim stent application in pyloric and colonic obstructions. Z Gastroenterol. 2001;39:957–960. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han HW, Lee IS, Park JM, et al. Self-expandable metallic stent therapy for a gastrointestinal benign stricture. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;37:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piesman M, Kozarek RA, Brandabur JJ, et al. Improved oral intake after palliative duodenal stenting for malignant obstruction: a prospective multicenter clinical trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2404–2411. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Acunas B, Poyanli A, Rozanes I. Intervention in gastrointestinal tract: the treatment of esophageal, gastroduodenal and colorectal obstructions with metallic stents. Eur J Radiol. 2002;42:240–248. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(02)00031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laasch HU, Martin DF, Maetani I. Enteral stents in the gastric outlet and duodenum. Endoscopy. 2005;37:74–81. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-826103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng YS, Li MH, Chen WX, Chen NW, Zhuang QX, Shang KZ. Comparison of different intervention procedures in benign stricture of gastrointestinal tract. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:410–414. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i3.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Song HY, Park SI, Do YS, et al. Expandable metallic stent placement in patients with benign esophageal strictures: results of long-term follow-up. Radiology. 1997;203:131–136. doi: 10.1148/radiology.203.1.9122381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paul L, Pinto I, Gómez H, Fernández-Lobato R, Moyano E. Metallic stents in the treatment of benign diseases of the colon: preliminary experience in 10 cases. Radiology. 2002;223:715–722. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2233010866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Small AJ, Young-Fadok TM, Baron TH. Expandable metal stent placement for benign colorectal obstruction: outcomes for 23 cases. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:454–462. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9453-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim HJ, Park JJ, Kang CD, et al. Effect of the temporary placement of stent in benign pyloric stenosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:P153. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanbiervliet G, Filippi J, Karimdjee BS, et al. The role of clips in preventing migration of fully covered metallic esophageal stents: a pilot comparative study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:53–59. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1827-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cwikiel W, Willén R, Stridbeck H, Lillo-Gil R, von Holstein CS. Self-expanding stent in the treatment of benign esophageal strictures: experimental study in pigs and presentation of clinical cases. Radiology. 1993;187:667–671. doi: 10.1148/radiology.187.3.8497612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fry SW, Fleischer DE. Management of a refractory benign esophageal stricture with a new biodegradable stent. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:179–182. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanaka T, Takahashi M, Nitta N, et al. Newly developed biodegradable stents for benign gastrointestinal tract stenoses: a preliminary clinical trial. Digestion. 2006;74:199–205. doi: 10.1159/000100504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]