Highlights

► Laser-assisted transcutaneous immunotherapy is equally efficient as classical SCIT. ► TCIT is a painless alternative to SCIT for the treatment of allergic diseases. ► CpG ODN suppress induction of TH2 reactions via the skin.

Abbreviations: SIT, Allergen-specific immunotherapy; Th, T helper; SCIT, Subcutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy; SLIT, Sublingual allergen-specific immunotherapy; P.L.E.A.S.E.®, Precise laser epidermal system; TCIT, Transcutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy; TCI, Transcutaneous immunization; BAL, Bronchoalveolar lavage; BALF, Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

Keywords: Type I allergy, Immunotherapy, Transcutaneous, Laser microporation, Skin immunization, CpG oligodeoxynucleotides

Abstract

Background

Two main shortcomings of classical allergen-specific immunotherapy are long treatment duration and low patient compliance. Utilizing the unique immunological features of the skin by transcutaneous application of antigen opens new approaches not only for painless vaccine delivery, but also for allergen-specific immunotherapy. Under certain conditions, however, barrier disruption of the skin favors T helper 2-biased immune responses, which may lead to new sensitizations.

Methods

In a prophylactic approach, an infra-red laser device was employed, producing an array of micropores of user-defined number, density, and depth on dorsal mouse skin. The grass pollen allergen Phl p 5 was administered by patch with or without the T helper 1-promoting CpG oligodeoxynucleotide 1826 as adjuvant, or was subcutaneously injected. Protection from allergic immune responses was tested by sensitization via injection of allergen adjuvanted with alum, followed by intranasal instillation. In a therapeutic setting, pre-sensitized mice were treated either by the standard method using subcutaneous injection or via laser-generated micropores. Sera were analyzed for IgG antibody subclass distribution by ELISA and for IgE antibodies by a basophil mediator release assay. Cytokine profiles from supernatants of re-stimulated lymphocytes and from bronchoalveolar lavage fluids were assessed by flow cytometry using a bead-based assay. The cellular composition of lavage fluids was determined by flow cytometry.

Results

Application of antigen via micropores induced T helper 2-biased immune responses. Addition of CpG balanced the response and prevented from allergic sensitization, i.e. IgE induction, airway inflammation, and expression of T helper 2 cytokines. Therapeutic efficacy of transcutaneous immunotherapy was equal compared to subcutaneous injection, but was superior with respect to suppression of already established IgE responses.

Conclusions

Transcutaneous immunotherapy via laser-generated micropores provides an efficient novel platform for treatment of type I allergic diseases. Furthermore, immunomodulation with T helper 1-promoting adjuvants can prevent the risk for new sensitization.

1. Introduction

Effective allergen-specific immunotherapy (SIT), regardless if performed by subcutaneous injections (SCIT) or sublingual application using droplets or tablets (SLIT), is perceived as an intervention to redirect inappropriate and exaggerated TH2 responses against allergens. Crucial events for this immune deviation are the preferential production of TH1 cytokines such as IFN-γ, and the induction of IL-10/TGF-β secretion by T regulatory cells in blood and inflamed airways [1]. Furthermore, suppression of allergen-specific IgE and induction of IgG4, and suppression of mast cells, basophils, and eosinophils contribute to the control of allergen-specific immune responses associated with SIT [2]. Despite its verifiable clinical success [3,4], only a small percentage of patients prefer this therapy to symptomatic treatment [5,6], and drop-out rates are considerable [7,8], mainly due to therapy duration of 3-5 years and local (SLIT) and/or systemic (SCIT) side effects [9,10]. The ideal SIT approach should therefore (i) target a tissue rich in immunocompetent cells to increase efficacy, thereby reducing the number of required doses, (ii) employ a needle-free administration method, and (iii) avoid contact with the circulation to minimize the risk of systemic side effects. Cutaneous delivery perfectly fulfills these prerequisites as the skin is easily accessible, harbors high numbers of antigen presenting cells, provides non-vascularized superficial layers, and delivery techniques avoiding needle and syringe have become available. In our current study, we used one of these platforms, the P.L.E.A.S.E® (Precise Laser Epidermal System) device for fractional ablation of superficial skin layers and the creation of micropores. This novel technology employs a diode-pumped Er:YAG laser, which emits light at 2.94 μm, corresponding to a major absorption peak of water molecules. Their excitation and evaporation leads to formation of aqueous micropores with a diameter of approx. 150 μm. Due to extremely short energy pulses, heat transfer to neighboring tissue is negligible. Using a scanning laser technology, an array of several hundred identical micropores of pre-defined number, density and depth can be sequentially created within a few seconds. In contrast to other transcutaneous vaccination methods, the P.L.E.A.S.E® laserporation system is easily adaptable to target appropriate skin layers in different species/individuals by adjusting the number of pulses per pore. Originally intended for increased delivery of small molecular weight compounds [11–13], in vivo transport of functionally intact proteins, such as antibodies, via P.L.E.A.S.E® -generated micropores has also been demonstrated [14].

Epicutaneous immunotherapy performed by application of allergen extracts to an area at the volar forearm, which had been pre-treated by needle scarification, was already described more than 50 years ago [15]. Recently, studies in mice and humans revisited this approach replacing needle scarification by adhesive tape stripping [16,17] or application of an occlusive chamber to increase skin permeability by hydration [18,19]. However, epicutaneous immunization on barrier-disrupted skin has been linked with the induction of TH2-biased responses [20,21], and sensitization to allergens [22,23]. Similarly, we also found that cutaneous delivery of different antigens via laser-generated micropores can lead to the generation of TH2-driven immunity[24]. Triggering of this immune response type would render transcutaneous immunotherapy (TCIT) problematic for treatment of type I allergy. Especially when using poorly defined allergen extracts, even a minimal risk for new sensitizations against previously unrecognized components has to be avoided. Therefore, the use of proper adjuvants, which can suppress TH2 responses in the skin, has to be considered. It has been previously shown that topical application of adjuvant to the site of vaccination leads to activation and migration of antigen presenting cells to skin draining lymph nodes [25]. In our present work we used a major timothy grass pollen allergen adjuvanted with CpG oligodeoxynucleotides (ODN) 1826, which are known for their TH1-promoting immunomodulatory capacity [26]. Furthermore, we compared the efficacy of TCIT with subcutaneous injection, which is the standard application in SIT.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

BALB/c females, aged 6-8 weeks, were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Sulzfeld, Germany) and maintained at the animal facility of the University of Salzburg. All animal experiments were conducted according to local guidelines approved by the Austrian Ministry of Science (Permit Number: GZ 66.012/0004-II/10b/2010), and in accordance with EU Directive 2010/63/EU.

2.2. Laser microporation

The day before laser microporation, mice were shaved on their back with a clipper, and depilatory cream was used to remove residual hair keeping the animals under inhalational anesthesia with isoflurane. Micropores were generated using the P.L.E.A.S.E.® device (Pantec Biosolutions AG, Ruggell, Liechtenstein) by placing mice, anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of ketamine/xylazine (80 mg ketamine, 7.5 mg xylazine per kg body weight), with their back at the focal length of the laser. Laser parameters, i.e. number of pores/cm2, number of pulses per pore, and fluence (energy applied per unit area) were pre-programmed using the device software. For vaccination as well as immunotherapy, 4 pulses with a fluence of 1.9 J/cm2 per pulse were applied, and 500 pores/cm2 (circular area, 1 cm diameter) were generated. With these settings a pore depth of approximately 30-40 μm penetrating well into the dermis was achieved, as previously described [24]. Antigen with or without adjuvant was applied by a patch consisting of a 10 mm × 10 mm piece of gauze (Aluderm®, W. Soehngen, Taunusstein-Wehen, Germany) soaked with the antigen solution and an adhesive tape (OpSite Flexifix, Smith&Nephew, Schenefeld, Germany). The patch was removed after 24 h.

2.3. Vaccination

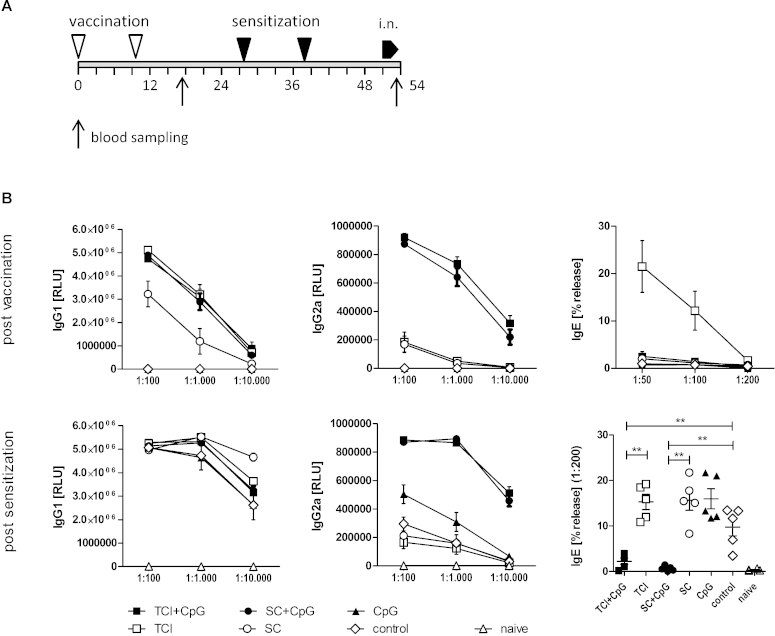

Immunizations were performed twice (day 0 and day 10) by application of 10 μg recombinant Phl p 5 (Biomay AG, Vienna, Austria) in 80 μL PBS, with or without additional 100 μg CpG ODN 1826 (Biomers, West-Ulm, Germany), onto a single laserporated skin area, or by s.c. injection of the same amount of antigen with or without adjuvant. Starting on day 28, immunized animals (5 animals per group) and untreated controls (n = 5) were sensitized by two intraperitoneal injections with 1 μg Phl p 5 in 100 μL PBS adjuvanted with 100 μL Al(OH)3, followed by 3 intranasal instillations on 3 consecutive days of 1 μg Phl p 5 in 40 μL PBS. On day 54, animals were sacrificed and bronchoalveolar lavages (BALs) were performed. Blood samples were drawn on days 17 and 53. A detailed experimental schedule is presented in Fig. 1A.

Fig. 1.

Prophylactic vaccination. (A) BALB/c mice (n = 5) were vaccinated transcutaneously via laser-generated micropores (TCI) or by subcutaneous injection (SC) with or without CpG ODN (“vaccination”), or with CpG ODN alone (CpG; applied transcutaneously) and subsequently sensitized by intraperitoneal injection of alum-adsorbed allergen (“sensitization”), followed by intranasal allergen challenge (“i.n.”). Non pre-vaccinated, but sensitized animals (“control”) and naïve animals served as controls. (B) Serum samples post vaccination and post sensitization were analyzed for allergen-specific IgG1, IgG2a, and IgE by ELISA or RBL release assay at the indicated serum dilutions. Data are shown as means ± SEM or individual data points. ELISA data are shown as relative light units (RLU) and RBL data as percentage of maximal release (% release). **P < 0.01. Post-vaccination data of panel 1B has been previously published [24].

2.4. Specific immunotherapy

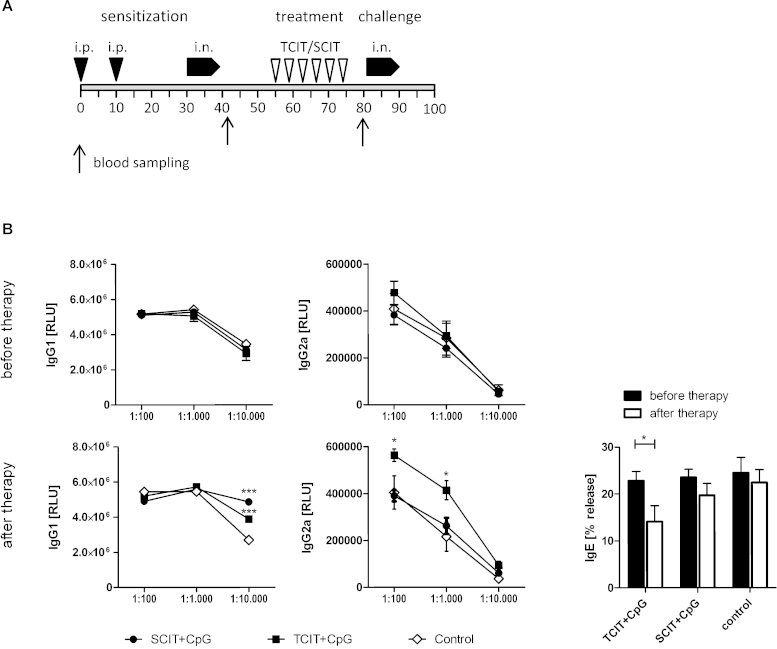

For therapy, mice were sensitized twice within 10 days by intraperitoneal injections with 1 μg Phl p 5 in 100 μL PBS adjuvanted with 100 μL Al(OH)3, followed by two series of 3 intranasal instillations on 3 consecutive days of 1 μg Phl p 5 in 40 μL PBS. Specific immunotherapy was performed twice a week for three weeks with 50 μg recombinant Phl p 5 adjuvanted with 100 μg CpG ODN, applied as skin patch onto microporated skin areas (one non-overlapping area per treatment) or by s.c. injection (7 animals per group). Control animals (n = 6) were left untreated. Mice were challenged with another 2 series of intranasal instillations, and sacrificed on day 90. Blood samples were collected on days 41 (after sensitization), and 80 (after therapy). An overview of the experimental schedule is given in Fig. 4A.

Fig. 4.

Allergen-specific immunotherapy. (A) BALB/c mice (n = 7; control group: n = 6) were sensitized by intraperitoneal injection of alum-adsorbed allergen, followed by intranasal allergen challenge (“sensitization”). Subsequently, animals were treated by transcutaneous immunotherapy via laser-generated micropores (TCIT) or subcutaneous injections (SCIT) with CpG-adjuvanted allergen, followed by a final intranasal challenge (i.n.). (B) Allergen-specific serum IgG1, IgG2a, and IgE was assessed before and after specific immunotherapy. Data are shown as means ± SEM or individual data points. ELISA data are shown as relative light units (RLU) and RBL data as percentage of maximal release (% release). *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

2.5. Serology and cytokines

Sera were analysed for Phl p 5-specific IgG1 and IgG2a by a luminescence-based ELISA at indicated serum dilutions lying within the linear range of the assay. Biologically functional IgE was determined by an in vitro basophil release assay as described [27]. Briefly, rat basophil leukemia cells (RBL-2H3) were incubated with sera at indicated dilutions for 2 h followed by addition of recombinant allergen, leading to cross-linking of FcɛR-bound IgE and mediator release from the cells. Beta-hexosaminidase in supernatants thereof was determined by addition of 4-MUG, a substrate forming stable complexes with the enzyme, which can be detected by fluorescence spectroscopy (λex360 nm/λem465 nm). Splenocytes were cultured in the presence or absence of 10 μg/mL recombinant Phl p 5 for 3 days and cytokine profiles in supernatants thereof were assessed via mouse TH1/TH2/TH17/TH22 13plex FlowCytomix multiplex kit combined with the mouse GM-CSF FlowCytomix simplex kit (eBioscience, San Diego, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Additionally, TGF-β1 was measured using a human/mouse TGF-β1 ELISA Ready-SET-Go! kit (eBioscience, San Diego, USA).

2.6. Analysis of bronchoalveolar lavages

At the end of the experimental schedule, animals were sacrificed and bronchoalveolar lavages were performed as described [28]. Cells were stained with CD45-FITC, CD4-APC/Cy7, CD19-PE, Gr1-APC (Biolegend or eBioscience, San Diego USA). Eosinophils were distinguished from other leukocyte populations by their CD45med Gr1low side-scatterhigh phenotype. Cytokine profiles of lavage fluids were established using the mouse TH1/TH2/TH17/TH22 13plex FlowCytomix multiplex kit (eBioscience, San Diego, USA). Neutrophil derived peroxidase activity in BALF was determined by mixing 50 μL of BALF with 50 μL of BM Chemiluminescence ELISA Substrate (POD) (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and measuring the resulting luminescence on an Infinite 200 PRO reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland).

3. Statistical analysis

Statistical significance between groups was assessed by unpaired Student's t-test (alpha = .05) using SigmaStat 2.0. Groups that failed normality test were compared using Mann-Whitney rank sum test. Multiple comparisons of serum titrations were performed by two-tailed ANOVA as indicated in the text. Correlation analysis was done using Spearman's Rank Correlation.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Effects of transcutaneous immunization on subsequent sensitization to allergens

We previously found that similar to other methods of cutaneous antigen delivery, transcutaneous immunization (TCI) via laser-generated micropores can lead to induction of a TH2-biased serological profile including the secretion of IgE and generation of IL-4 secreting TH2 cells, both of which can be suppressed by the addition of TLR agonists including CpG ODN[24]. In a first set of experiments employing the major timothy grass pollen allergen Phl p 5, we investigated the effect of TCI with and without CpG ODN on the resulting immune response and its impact on subsequent allergic sensitization by alum-adsorbed protein followed by airway provocation (see Fig. 1A for experimental schedule).

4.1.1. CpG ODN prevent transcutaneous IgE induction and protect from subsequent alum-induced sensitization

As shown in Fig. 1B (post vaccination), TCI in the absence of adjuvant was more potent in inducing antigen specific IgG1 compared to s.c. injection (P < 0.01; ANOVA) while no differences in the IgG2a levels were observed. However, only TCI also induced IgE as measured by basophil release assay. This TH2 priming effect via the skin has been recently associated to stress-induced activation of dendritic epidermal T cells (DETC) and NKT cells producing TH2 promoting cytokines such as IL-13, IL-25, and IL-33 [29]. Skin barrier disruption also activates keratinocytes to secrete TSLP which promotes survival, maturation, and migratory properties of freshly isolated Langerhans cells and the production of pro-allergic cytokine profiles in co-cultured CD4+ T cells [30]. High expression of TSLP in keratinocytes has been found in patients with atopic dermatitis, as well as in activated mast cells [31].

Addition of CpG ODN restored the IgG1 levels after s.c. injection to the levels obtained by TCI and boosted IgG2a for both application methods (P < 0.0001 vs. non-adjuvanted delivery; ANOVA) and also completely suppressed IgE induction after TCI, confirming previous data demonstrating that CpG ODN can shift skin vaccination induced TH2 responses towards TH1 [32]. Moreover, addition of CpG ODN during vaccination suppressed the subsequent sensitization by alum-adsorbed allergen (Fig. 1B, post sensitization) in an antigen specific manner (P < 0.01 vs. control; t-test). Although pre-treatment with CpG alone (antigen unspecific) also induced elevated levels of IgG2a after sensitization (P < 0.05 vs. control; ANOVA), indicating the persistence of a TH1 modulating milieu at the time-point of sensitization, this effect was not sufficient to prevent the induction of allergen-specific IgE. Despite the induction of IgE by TCI without adjuvant during the primary immune response, IgE levels after sensitization were comparable to those observed in the s.c. injected group.

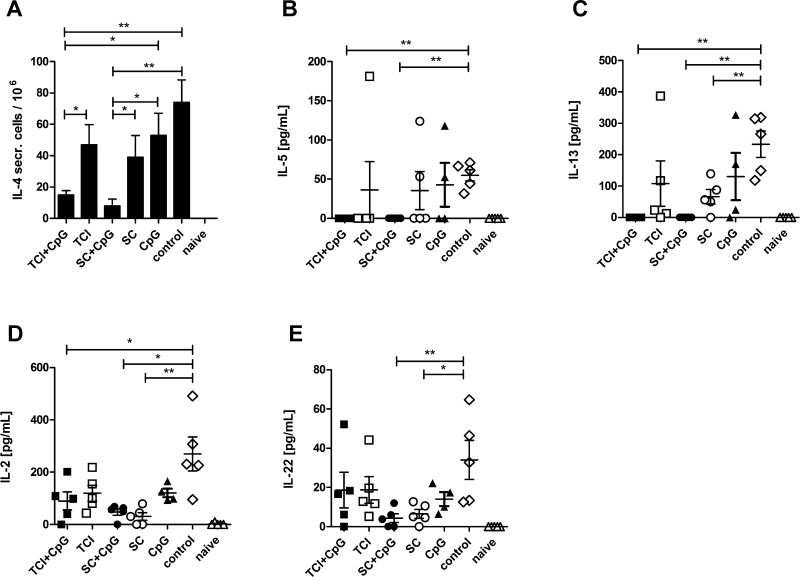

4.1.2. CpG ODN are necessary for suppression of TH2 cytokines but not IL-22

When evaluating the cytokine profile of re-stimulated splenocytes at the end of the experiment, we found a clear suppression of IL-4 (Fig. 2A), IL-5 (Fig. 2B), and IL-13 (Fig. 2C) by CpG adjuvanted vaccination by either the transcutaneous or subcutaneous route, although s.c. injection and TCI alone also (to a lesser degree) suppressed IL-13. Surprisingly, we found no induction of IFN-γ or TNF-α (not shown), indicative of a TH1 response; on the contrary, pre-vaccination with or without CpG suppressed IL-2 (Fig. 2D) compared to sensitization controls. Finally, s.c. injection suppressed the TH17/TH22 cytokine IL-22 (Fig. 2E), which may play a role in the early onset of allergic lung inflammation [33] but also has been implicated as immunosuppressive during early immune responses [34]. Although we could not detect IL-17, sensitization with alum-adsorbed allergen may lead to inflammasome activation and generation of IL-22 secreting TH17 cells [35]. Both, TH1 or TH2 responses primed by pre-vaccination could suppress the TH17 responses [36] induced by the sensitization protocol and therefore explain the observed reduction in IL-22.

Fig. 2.

Cytokine profile of pre-vaccinated animals. Cytokine production of splenocytes from pre-vaccinated and control animals was analyzed after sensitization. The number of IL-4-secreting cells was determined by ELISPOT (A) and IL-5, IL-13, IL-2, and IL-22 was measured in supernatants of re-stimulated splenocytes. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 5; CpG only group: n = 4) or individual data points. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

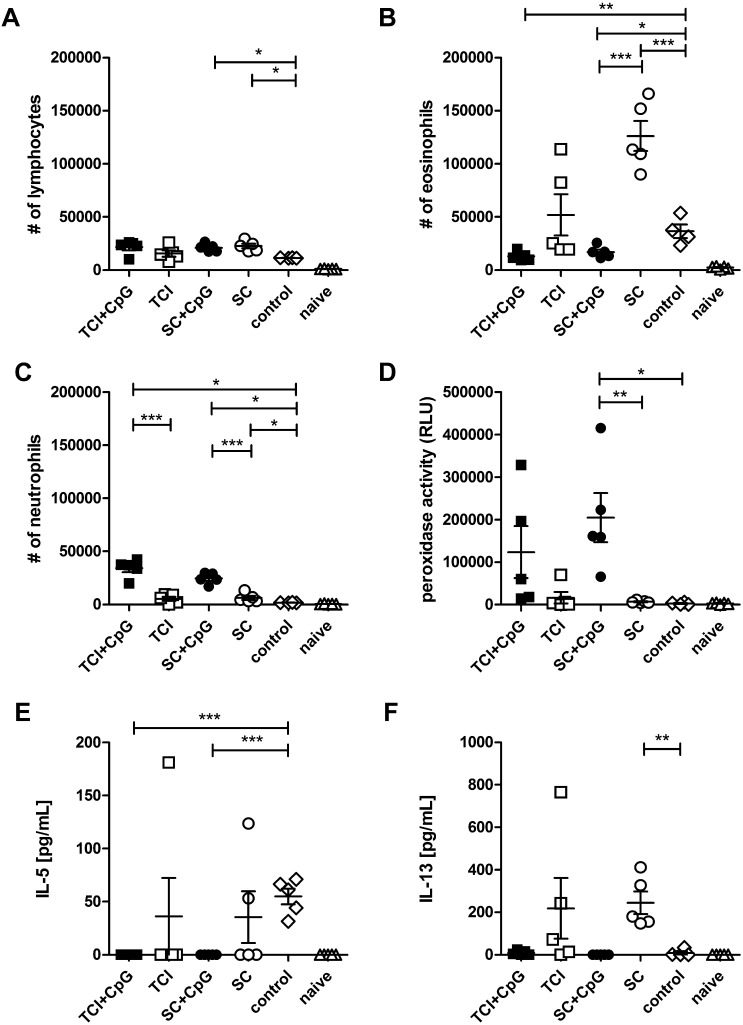

4.1.3. Pre-vaccination prevents or exacerbates eosinophilic inflammation of the airways depending on the presence of CpG ODN

As shown in Fig. 3, transcutaneous and subcutaneous vaccination mildly elevated the number of BAL lymphocytes independent of CpG co-administration (Fig. 3A), but only CpG ODN adjuvanted allergen abrogated sensitization induced BAL eosinophilia (Fig. 3B) which correlated with reduced levels of IL-5 (Fig. 3E, P < 0.01; Spearman) and IL-13 (Fig. 3F, P < 0.0001; Spearman) in BALF. On the contrary, pre-vaccination without adjuvant exacerbated inflammation as indicated by increased numbers of eosinophils and highly elevated levels of IL-13. These data show that both, TCI as well as s.c. injection of recombinant allergen into naïve animals can have a negative impact on later acquired allergic sensitization and this has to be taken into consideration with regards to prophylactic vaccination strategies against allergy. In contrast to Haapakoski et al., CpG ODN co-administration did not induce enhanced levels of IFN-γ in BALF (not shown) [37], but similar to Duechs et al. [38], we found elevated levels of BAL neutrophils (Fig. 3C) which were associated with increased levels of neutrophil derived peroxidase activity in BALF (Fig. 3D). However, at least with a protective approach using RNA vaccines, we previously found that this increase in neutrophils in vaccinated mice is only present during the acute phase of lung inflammation, while after repeated airway exposures, the levels of neutrophils return to baseline while protection from eosinophila is maintained (unpublished observations).

Fig. 3.

Lung infiltration of pre-vaccinated animals. The number of BAL infiltrating leukocytes in pre-vaccinated and control animals were analyzed after sensitization. The number of total lymphocytes (A), eosinophils (B), neutrophils (C) per BAL are shown. Peroxidase activity in BALF is displayed as relative light units (D), and IL-5 (E) and IL-13 (F) concentrations in BALF were measured by FlowCytomix assay. Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 5; control group: n = 4) and individual data points. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

4.2. Transcutaneous immunotherapy of allergy is equally efficient compared to standard SCIT

As our previous data indicated that both, s.c. as well as transcutaneous application of allergen in a prophylactic setting may have detrimental side effects in the absence of a TH2 blocking adjuvant, we next investigated a CpG-adjuvanted therapeutic approach, comparing the transcutaneous with the subcutaneous route. For that purpose, mice were sensitized and airway inflammation was induced, followed by a therapeutic intervention and a final re-challenge via the airways. The experimental schedule is shown in Fig. 4A. Before the start of the therapy, IgG1, IgG2a (Fig. 4B – top panel), and IgE levels (Fig. 4B – bottom right panel) were similar in all groups.

4.2.1. TCIT, but not SCIT, shifts the serological profile towards TH1 and suppresses established IgE responses

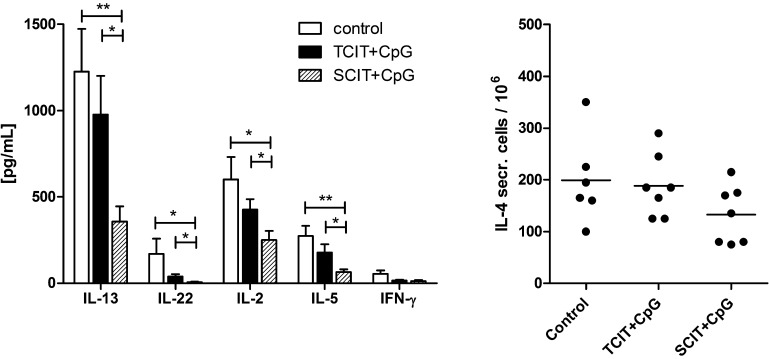

TCIT and SCIT with CpG-adjuvanted allergen significantly increased the levels of IgG1, but only TCIT also elevated IgG2a, indicating a shift towards TH1 at least on the serological level. This is in accordance with the observation that only TCIT significantly reduced allergen-specific IgE (Fig. 4B). However, cytokine responses of in vitro re-stimulated splenocytes showed a stronger reduction of TH2 (IL-4, IL-5, IL-13), TH1 (IL-2, IFN-γ) and TH17 (IL-22) cytokines after SCIT (Fig. 5). As IFN-γ is the pivotal switch factor for IgG2a, the lack of IFN-γ (and the modest suppression of TH2/TH17 cytokines) suggests, that TCIT induced TH1 cells are either short-lived and no longer present, or more likely do not primarily home into the spleen but to the skin. Recent findings implicating the importance of locally residing effector memory T cells after skin immunization have been reviewed in [39].

Fig. 5.

Splenic cytokine profile after specific immunotherapy. Cytokine levels were measured in supernatants of re-stimulated splenocytes (A) or by ELISPOT assay (B). Data are shown as means ± SEM (n = 7; control group: n = 6) or individual data points. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

4.2.2. Specific immunotherapy successfully downregulates established inflammation of the lung

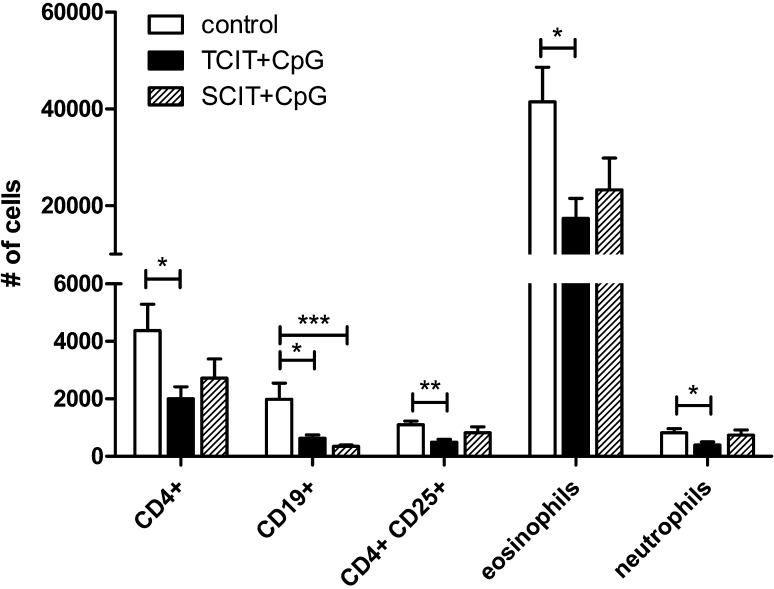

As demonstrated in Fig. 6, TCIT downregulates the numbers of infiltrating cells in BALF. Compared to the untreated control animals, TCIT significantly reduced the number of CD4+ T-cells, CD19+ B-cells, as well as eosinophils. In contrast to the acute inflammation seen in the prophylactic situation (Fig. 3C), in the therapeutic setting CpG-adjuvanted immunotherapy did not increase the number of neutrophils in the lung, but on the contrary, TCIT even significantly decreased them. Therapeutic efficacy of TCIT at least equaled that of SCIT and was independent of the influx of CD4 + CD25+ regulatory T cells into the lung, as their percentage of total CD4+ cells in BAL remained constant in all groups and therefore their absolute number simultaneously decreased.

Fig. 6.

Effect of specific immunotherapy on lung infiltration. After an intranasal re-challenge (post therapy), BAL infiltrating leukocytes were assessed. The numbers of different leukocyte subsets per BAL are shown as means ± SEM (n = 7; control group: n = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

5. Conclusions

Only recently, skin immunization has been put into the focus of intense research due to increasing knowledge about the immunological functions of various skin resident cell types and their complex interplay thus contributing to innate as well as adaptive immunity [40]. Although one has to keep in mind that murine skin differs from humans not only in thickness but also in cellular composition [41] and TLR distribution [40], remarkable similarities in the functionality of the skin DC network exist [42]. Allergen-specific immunotherapy via the skin has been re-visited as an attractive alternative to current therapeutic practices. Although recent clinical trials [16,17] and pre-clinical data from our own group [43] have shown safety and therapeutic efficacy of unadjuvanted epicutaneous or transcutaneous immunotherapy, in this work we demonstrate that on a naïve background, TCI with allergen can potentially induce allergic sensitization or exacerbate subsequently acquired allergic disease. In this context, application of poorly defined extracts containing allergenic components against which a patient may still be naïve, has to be considered with caution. In our current work, we demonstrate that co-application of CpG can increase the safety of the therapy by abrogating the TH2 polarizing potential of skin immunization. In a clinical study, house dust mite allergen adjuvanted with CpG ODN packaged into virus-like particles was used for SCIT and found to be safe and well tolerated [44]. Although we also observed no CpG-associated side effects, future studies will be needed to identify adjuvants for epi/transcutaneous administration with an optimal risk/benefit ratio.

Author contributions

MH performed experiments and did data acquisition. EW oversaw the conduct of the study and participated in data interpretation. RW and SS designed the study, performed data analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. CB gave technical assistance and took part in study conception. JT performed study conception, data interpretation and manuscript drafting. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript and approved the final version.

Disclosure statement

MH, EW, and SS have received funding from the Austrian Science Fund. RW and JT have received research support from the Christian Doppler Research Association and from Biomay AG, Vienna, Austria. CB is CEO of Pantec Biosolutions AG.

Funding

This work was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), Project # P21125, Project # W1213, the Christian Doppler Research Association, and Biomay AG, Vienna, Austria. The funders had no role in study design, in collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

References

- 1.Maggi E., Vultaggio A., Matucci A. T-cell responses during allergen-specific immunotherapy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12(February (1)):1–6. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32834ecc9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akdis C.A., Akdis M. Mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(January (1)):8–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.11.030. [18-27; quiz] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eifan A.O., Shamji M.H., Durham S.R. Long-term clinical and immunological effects of allergen immunotherapy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;11(December (6)):586–593. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32834cb994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobsen L., Niggemann B., Dreborg S., Ferdousi H.A., Halken S., Host A. Specific immunotherapy has long-term preventive effect of seasonal and perennial asthma: 10-year follow-up on the PAT study. Allergy. 2007;62(August (8)):943–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox L., Calderon M.A. Subcutaneous specific immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a review of treatment practices in the US and Europe. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(December (12)):2723–2733. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2010.528647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Werfel T. Epicutaneous allergen administration: a novel approach for allergen-specific immunotherapy? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(November (5)):1003–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.More D.R., Hagan L.L. Factors affecting compliance with allergen immunotherapy at a military medical center. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;88(April (4)):391–394. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senna G., Lombardi C., Canonica G.W., Passalacqua G. How adherent to sublingual immunotherapy prescriptions are patients? The manufacturers’ viewpoint. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(September (3)):668–669. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frew A.J., Sublingual immunotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(May (21)):2259–2264. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0708337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frew A.J., Allergen immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(February (2 Suppl. 2)):S306–S313. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bachhav Y.G., Heinrich A., Kalia Y.N. Using laser microporation to improve transdermal delivery of diclofenac: increasing bioavailability and the range of therapeutic applications. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2011;78(August (3)):408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2011.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachhav Y.G., Summer S., Heinrich A., Bragagna T., Bohler C., Kalia Y.N. Effect of controlled laser microporation on drug transport kinetics into and across the skin. J Control Release. 2010;146(August (1)):31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu J., Bachhav Y.G., Summer S., Heinrich A., Bragagna T., Bohler C. Using controlled laser-microporation to increase transdermal delivery of prednisone. J Control Release. 2010;148(November (1)):e71–e73. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu J., Kalaria D.R., Kalia Y.N., Erbium: YAG fractional laser ablation for the percutaneous delivery of intact functional therapeutic antibodies. J Control Release. 2011;156(November (1)):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2011.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blamoutier P., Blamoutier J., Guibert L. Traitement de la pollinose avec extraits de pollens par la méthode des quadrillages cutanés. Treatment of pollinosis with pollen extracts by the method of cutaneous quadrille rulingPresse Med. 1959;67(December):2299–2301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senti G., Graf N., Haug S., Ruedi N., von Moos S., Sonderegger T. Epicutaneous allergen administration as a novel method of allergen-specific immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(November (5)):997–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senti G., von Moos S., Tay F., Graf N., Sonderegger T., Johansen P. Epicutaneous allergen-specific immunotherapy ameliorates grass pollen-induced rhinoconjunctivitis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled dose escalation study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(January (1)):128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dupont C., Kalach N., Soulaines P., Legoue-Morillon S., Piloquet H., Benhamou P.H. Cow's milk epicutaneous immunotherapy in children: a pilot trial of safety, acceptability, and impact on allergic reactivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(May (5)):1165–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mondoulet L., Dioszeghy V., Ligouis M., Dhelft V., Dupont C., Benhamou P.H. Epicutaneous immunotherapy on intact skin using a new delivery system in a murine model of allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2010;40(April (4)):659–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strid J., Callard R., Strobel S. Epicutaneous immunization converts subsequent and established antigen-specific T helper type 1 (Th1) to Th2-type responses. Immunology. 2006;119(September (1)):27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Strid J., Hourihane J., Kimber I., Callard R., Strobel S. Disruption of the stratum corneum allows potent epicutaneous immunization with protein antigens resulting in a dominant systemic Th2 response. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34(August (8)):2100–2109. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.He R., Kim H.Y., Yoon J., Oyoshi M.K., MacGinnitie A., Goya S. Exaggerated IL-17 response to epicutaneous sensitization mediates airway inflammation in the absence of IL-4 and IL-13. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(October (4)):761–770.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strid J., Hourihane J., Kimber I., Callard R., Strobel S. Epicutaneous exposure to peanut protein prevents oral tolerance and enhances allergic sensitization. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35(June (6)):757–766. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiss R., Hessenberger M., Kitzmuller S., Bach D., Weinberger E.E., Krautgartner W.D. Transcutaneous vaccination via laser microporation. J Control Release. 2012;162(September (2)):391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2012.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guebre-Xabier M., Hammond S.A., Epperson D.E., Yu J., Ellingsworth L., Glenn G.M. Immunostimulant patch containing heat-labile enterotoxin from Escherichia coli enhances immune responses to injected influenza virus vaccine through activation of skin dendritic cells. J Virol. 2003;77(May (9)):5218–5225. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5218-5225.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bode C., Zhao G., Steinhagen F., Kinjo T., Klinman D.M. CpG DNA as a vaccine adjuvant. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2011;10(April (4)):499–511. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hartl A., Weiss R., Hochreiter R., Scheiblhofer S., Thalhamer J. DNA vaccines for allergy treatment. Methods. 2004;32(March (3)):328–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabler M., Scheiblhofer S., Kern K., Leitner W.W., Stoecklinger A., Hauser-Kronberger C. Immunization with a low-dose replicon DNA vaccine encoding Phl p 5 effectively prevents allergic sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(September (3)):734–741. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strid J., Sobolev O., Zafirova B., Polic B., Hayday A. The intraepithelial T cell response to NKG2D-ligands links lymphoid stress surveillance to atopy. Science. 2011;334(December (6060)):1293–1297. doi: 10.1126/science.1211250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ebner S., Nguyen V.A., Forstner M., Wang Y.H., Wolfram D., Liu Y.J. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin converts human epidermal Langerhans cells into antigen-presenting cells that induce proallergic T cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(April (4)):982–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soumelis V., Reche P.A., Kanzler H., Yuan W., Edward G., Homey B. Human epithelial cells trigger dendritic cell mediated allergic inflammation by producing TSLP. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(July (7)):673–680. doi: 10.1038/ni805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beignon A.S., Briand J.P., Muller S., Partidos C.D. Immunization onto bare skin with synthetic peptides: immunomodulation with a CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotide and effective priming of influenza virus-specific CD4+ T cells. Immunology. 2002;105(February (2)):204–212. doi: 10.1046/j.0019-2805.2001.01357.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Besnard A.G., Sabat R., Dumoutier L., Renauld J.C., Willart M., Lambrecht B. Dual role of IL-22 in allergic airway inflammation and its cross-talk with IL-17A. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(May (9)):1153–1163. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201008-1383OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakagome K., Imamura M., Kawahata K., Harada H., Okunishi K., Matsumoto T. High expression of IL-22 suppresses antigen-induced immune responses and eosinophilic airway inflammation via an IL-10-associated mechanism. J Immunol. 2011;187(November (10)):5077–5089. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Besnard A.G., Togbe D., Couillin I., Tan Z., Zheng S.G., Erard F. Inflammasome-IL-1-Th17 response in allergic lung inflammation. J Mol Cell Biol. 2012;4(February (1)):3–10. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjr042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrington L.E., Hatton R.D., Mangan P.R., Turner H., Murphy T.L., Murphy K.M. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(November (11)):1123–1132. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haapakoski R., Karisola P., Fyhrquist N., Savinko T., Wolff H., Turjanmaa K. Intradermal cytosine-phosphate-guanosine treatment reduces lung inflammation but induces IFN-gamma-mediated airway hyperreactivity in a murine model of natural rubber latex allergy. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44(May (5)):639–647. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0355OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Duechs M.J., Hahn C., Benediktus E., Werner-Klein M., Braun A., Hoymann H.G. TLR agonist mediated suppression of allergic responses is associated with increased innate inflammation in the airways. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2011;24(April (2)):203–214. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Clark R.A. Skin-resident T cells: the ups and downs of on site immunity. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(February (2)):362–370. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bal S.M., Ding Z., van Riet E., Jiskoot W., Bouwstra J.A. Advances in transcutaneous vaccine delivery: do all ways lead to Rome? J Control Release. 2010;148(December (3)):266–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mestas J., Hughes C.C. Of mice and not men: differences between mouse and human immunology. J Immunol. 2004;172(March (5)):2731–2738. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guilliams M., Henri S., Tamoutounour S., Ardouin L., Schwartz-Cornil I., Dalod M. From skin dendritic cells to a simplified classification of human and mouse dendritic cell subsets. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40(August (8)):2089–2094. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bach D., Weiss R., Hessenberger M., Kitzmueller S., Weinberger E.E., Krautgartner W.D. Transcutaneous immunotherapy via laser-generated micropores efficiently alleviates allergic asthma in Phl p 5-sensitized mice. Allergy. 2012;67(November (11)):1365–1374. doi: 10.1111/all.12005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Senti G., Johansen P., Haug S., Bull C., Gottschaller C., Muller P. Use of A-type CpG oligodeoxynucleotides as an adjuvant in allergen-specific immunotherapy in humans: a phase I/IIa clinical trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39(April (4)):562–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]