Abstract

Background:

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) syndrome is an established and modifiable but under recognized risk factor for common disorders like stroke and hypertension.

Objective:

To assess awareness level of health care practitioners and medical students about OSA as a risk factor for stroke and hypertension.

Methods:

Questionnaire based survey with multiple response type and fill in the blanks type questions. The data was compiled and analyzed using SPSS version 19.

Results:

180 participants completed the survey questionnaire. Only 24 (13.3%) identified OSA as a reversible risk factor for ischemic stroke. 11 (6%) participants only could answer OSA as an identified risk factor for hypertension as per Seventh Joint National Committee report.

Conclusion:

This study reveals dismal level of awareness, among health professionals and medical students, about OSA being an established and modifiable risk factor for hypertension and ischemic stroke.

Keywords: Awareness, health professionals, hypertension, ischemic stroke, obstructive sleep apnoea

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is associated with hypertension, metabolic syndrome, diabetes, heart failure, coronary artery disease, arrhythmias, stroke, pulmonary hypertension, and neurocognitive and mood disorders.[1] The seventh report of joint national committee (JNC -7) on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure recognizes OSA as an identifiable risk factor for hypertension.[2] Studies have shown untreated OSA to be an independent risk factor for stroke and cardiovascular diseases.[3–9] Besides, co-existent OSA also has a negative impact on recovery of neurological functions and the survival of patients with stroke.[10] Poor awareness of OSA can lead to non-recognition of this modifiable risk factor. We report the finding of a survey conducted among healthcare professionals and medical students regarding the awareness of obstructive sleep apnea as vascular risk factor.

Methods

The study was conducted at Jawaharlal institute of postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Pondicherry, India, a tertiary care academic center in Southern India. The Ethics committee of the institute approved the study.

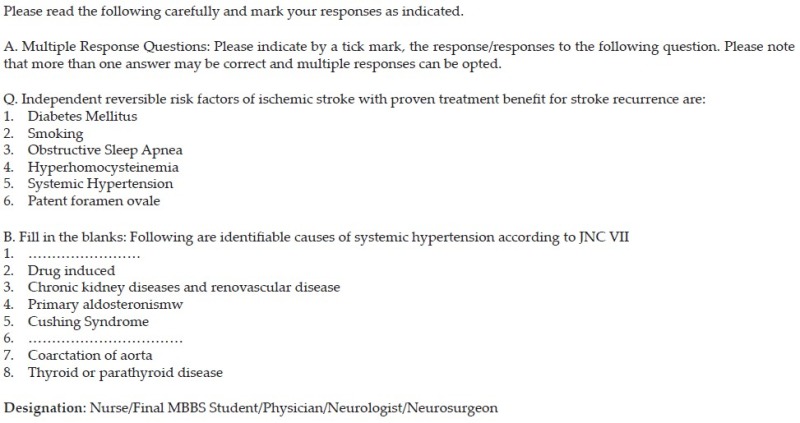

The study was conducted as a part of a pre-test survey done prior to Continuing medical education (CME) program conducted on the occasion of world stroke day during the year 2009 and 2011. The survey question consisted of a multiple response question and a fill in the blanks question (Appendix). The multiple response questions required the respondents to indicate what they considered reversible, independent risk factors for stroke. The options included conventionally recognized risk factors such as hypertension, smoking, and diabetes mellitus and putative factors such as patent foramen ovale and hyperhomocysteinemia, where evidence is less certain. These multiple options were kept as fillers to deemphasize the option of interest, obstructive sleep apnea. The second question involved the entire list of conditions listed in JNC-7 report as the identifiable causes of hypertension. This included sleep apnea, drug induced, chronic kidney disease, primary aldosteronism, Cushing’s syndrome, pheochromocytoma, coarctation of the aorta, and thyroid or parathyroid disease. The item number one, sleep apnea and item number six, pheochromocytoma were kept as blanks, which the respondents were instructed to fill-up. While the item number one formed the subject of interest, the item number six served as a “cue-deflector.” All participants filled the questions within a stipulated time of 20 min, under direct supervision of the investigators, before the start of the proceedings of the CME program. The data were compiled and analyzed using SPSS version 19.

Results

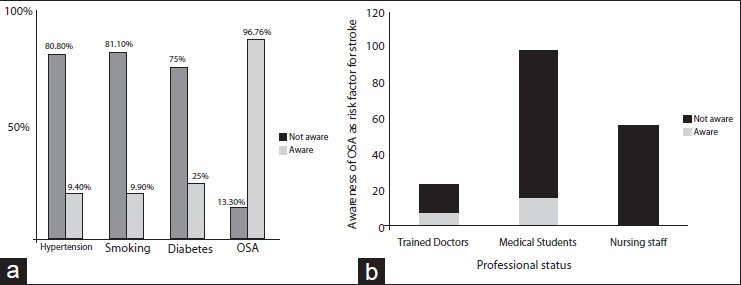

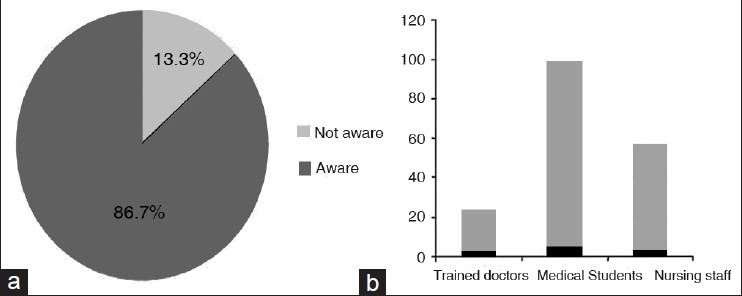

A total of 180 participants, consisting of specialist doctors (General Physicians, Neurologists, and Neurosurgeons), final year MBBS students, and qualified nursing staff completed the questionnaire. Among modifiable risk factor for ischemic stroke, OSA was identified by 24 (13.3%) participants. In the same category, hypertension was correctly identified by 145 (80.6%), smoking by 146 (81%), and diabetes mellitus by 135 (75%) participants [Figure 1a]. These responses were further analyzed according to type of participants, divided into categories [Figure 1b], as category 1: Trained doctors, category 2: Final MBBS students, and category 3: Nursing staff. On the second question of identifiable causes for hypertension as per JNC VII report, OSA was correctly identified by 11 (6.1%) participants only [Figure 2a]. The category wise distribution of this response is depicted in Figure 2b.

Figure 1.

Awareness of modifiable risk factors for ischemic stroke (hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus, obstructive sleep apnea [OSA]) in study participants (a) and Category wise distribution of awareness of OSA as established reversible risk factor for ischemic stroke (b) n = 180

Figure 2.

Awareness of obstructive sleep apnea as an identified risk factor for hypertension as per JNC-VII report: Among all participants (a) and as per categories of participants (b) n = 180

Discussion

This study reveals dismal level of awareness about OSA being an established and modifiable risk factor for hypertension and ischemic stroke among health professionals and medical students in a tertiary care academic institute in South India. Poor awareness of OSA was found at all levels of healthcare providers, from undergraduate students to specialist doctors and nursing staff. A similar study, conducted in Israel to assess the awareness level of primary care physicians about OSA, found that majority of primary care physicians did not ask relevant questions that could identify OSA, and most of them do not discuss the cardiovascular complication associated with disorder.[11] Other surveys, in Singapore and Croatia, on medical students’ and physicians’ behavior, attitude, and knowledge about sleep medicine revealed that sleep medicine knowledge is generally low in these groups.[12,13]

The lack of emphasis on OSA in undergraduate medical education curriculum and lack of formal training and continuing medical education programs on OSA at residency and practicing specialists’ level could be the most plausible explanations for the poor awareness of the consequences of this entity. It has been shown that teaching 3rd year medical students about OSA using a lecture and case-based discussion makes a difference to a clerkship objective-structured clinical examination assessing these competencies.[14] A complete undergraduate curriculum in chronobiology and sleep disorders should not only establish a knowledge base but also train students in clinical applications of this knowledge base, recognize the effects of sleep problems on professional training, and emphasize the public health implications of sleep disorders.[15] At residency level, case presentations and grand rounds should be seen as opportunities to present the concepts of sleep medicine and the recognition of sleep disorder. In addition, insertion of topics on sleep into routine clinical assessments of medical student performance, in both theory and practical examinations, could result in greater awareness about sleep-related disorders.[16] This is relevant for many specialties and subspecialties, such as general medicine, neurology, neurosurgery, psychiatry, family medicine, otorhinolaryngology, and anesthesiology. Besides nurses can contribute to knowledge about sleep and health promotion, provide primary care, disseminate information to patients, and enhance patient compliance with treatment[17] Hence, it is imperative that teaching curriculum for nurses at undergraduate and postgraduate levels should include the hitherto neglected fields of OSA and other sleep disorders.

Conclusion

There is a need to create a greater awareness, among medical fraternity, of OSA as a modifiable risk factor for stroke and hypertension. Such awareness can potentially translate into greater diagnostic suspicion, averting the non-diagnosis of OSA, with far reaching implications on prevention and treatment of morbidity and mortality associated with this syndrome.

Appendix: Questionnaire used for the survey

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

References

- 1.Mannarino MR, Di Filippo F, Pirro M. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23:586–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichtman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2034–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, Lee ET, Newman AB, Nieto FJ, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: Cross-sectional results of the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:19–25. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.1.2001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: An observational study. Lancet. 2005;365:1046–53. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arzt M, Young T, Finn L, Skatrud JB, Bradley TD. Association of sleep-disordered breathing and the occurrence of stroke. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1447–51. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200505-702OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parra O, Arboix A, Montserrat JM, Quintó L, Bechich S, García-Eroles L. Sleep-related breathing disorders: Impact on mortality of cerebrovascular disease. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:267–72. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00061503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez-García MA, Galiano-Blancart R, Román-Sánchez P, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Cabero-Salt L, Salcedo-Maiques E. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment in sleep apnea prevents new vascular events after ischemic stroke. Chest. 2005;128:2123–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.4.2123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1378–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dumitrascu R, Tiede H, Rosengarten B, Schulz R. Obstructive sleep apnea and stroke. Pneumologie. 2012;66:476–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reuveni H, Tarasiuk A, Wainstock T, Ziv A, Elhayany A, Tal A. Awareness level of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome during routine unstructured interviews of a standardized patient by primary care physicians. Sleep. 2004;27:1518–25. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahendran R, Subramaniam M, Chan YH. Medical students’ behaviour, attitudes and knowledge of sleep medicine. Singapore Med J. 2004;45:587–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kovaciæ Z, Marendiæ M, Soljiæ M, Pecotiæ R, Kardum G, Dogas Z. Knowledge and attitude regarding sleep medicine of medical students and physicians in Split, Croatia. Croat Med J. 2002;43:71–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Papp KK, Strohl KP. The effects of an intervention to teach medical students about obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Med. 2005;6:71–3. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2004.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strohl KP, Veasey S, Harding S, Skatrud J, Berger HA, Papp KK, et al. Competency-based goals for sleep and chronobiology in undergraduate medical education. Sleep. 2003;26:333–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strohl KP. Sleep medicine training across the spectrum. Chest. 2011;139:1221–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee KA, Landis C, Chasens ER, Dowling G, Merritt S, Parker KP, et al. Sleep and chronobiology: Recommendations for nursing education. Nurs Outlook. 2004;52:126–33. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]