Abstract

The small intestine is capable of taking up peptide nutrients of two or three amino acid residues, but the mechanism of intestinal assimilation of larger oligopeptides has not been established. The amino-oligopeptidase of the intestinal brush border possesses high specificity for oligopeptides having bulky side chains and is a candidate for a crucial role in the overall assimilation of dietary protein.

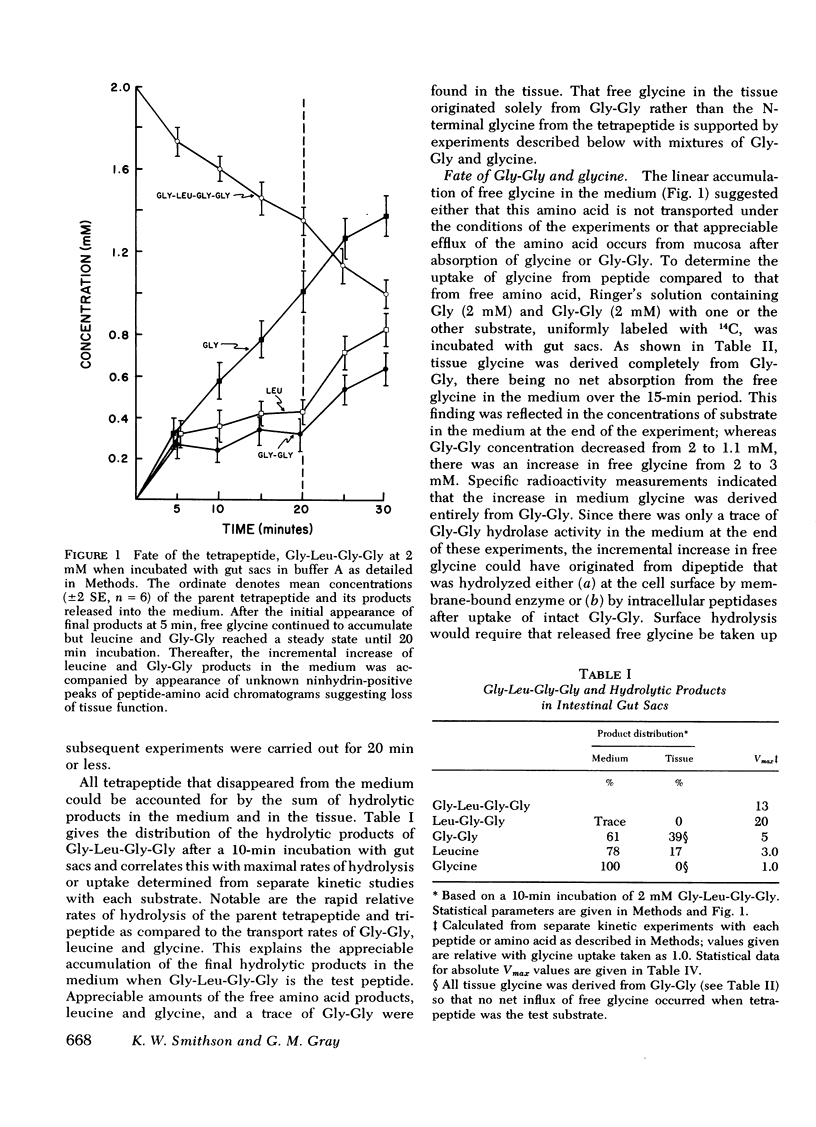

Rat jejunum was used for in vitro gut sac and in vivo perfusion experiments with Gly-l-Leu-Gly-Gly (2 mM) as the test substrate with analysis of parent peptide and products by automatic ion-exchange chromatography. In these experiments, the tetrapeptide disappeared rapidly from the test solution (20 μmol/s per cm2 in vitro; 17 μmol/s per cm2 in vivo) by sequential removal of amino acid residues from the N-terminus to yield amino acids and the C-terminal dipeptide. In gut sac experiments, 61-100% of these products of hydrolysis appeared in the incubation medium and the remainder in the tissue. In contrast, only small amounts of hydrolytic products were found within intestinal lumen in vivo.

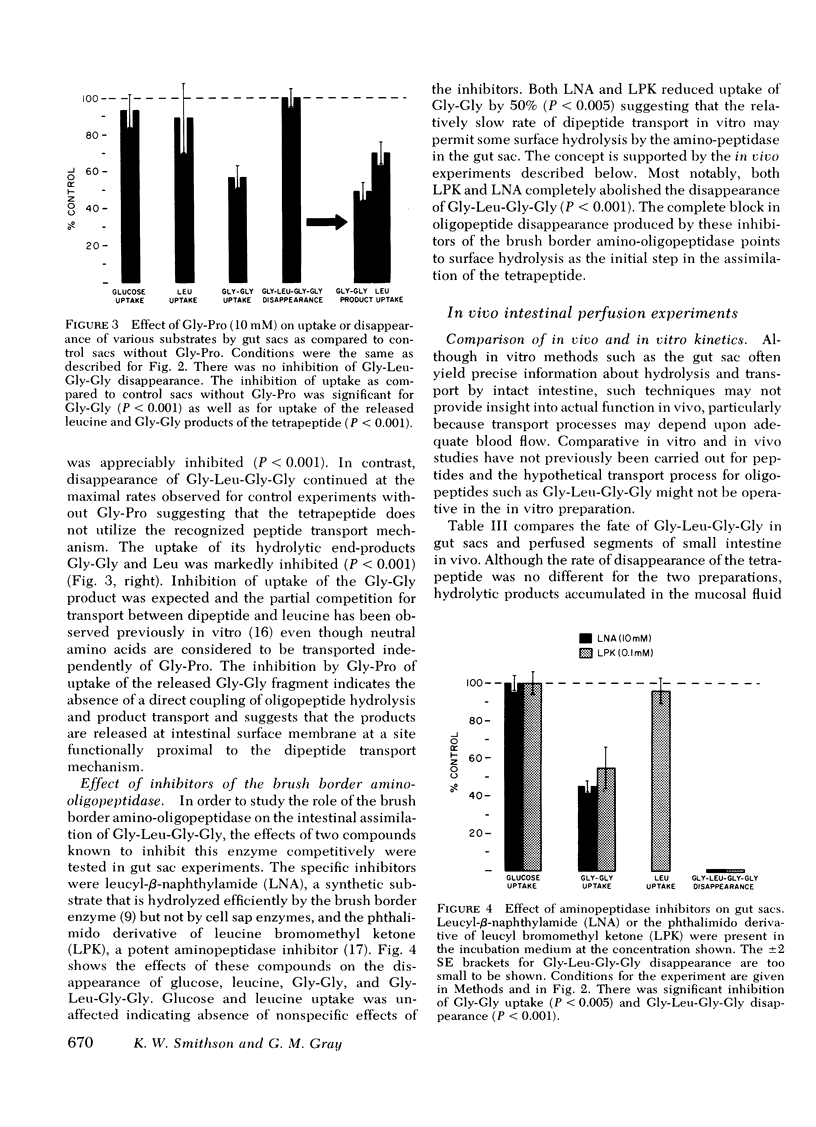

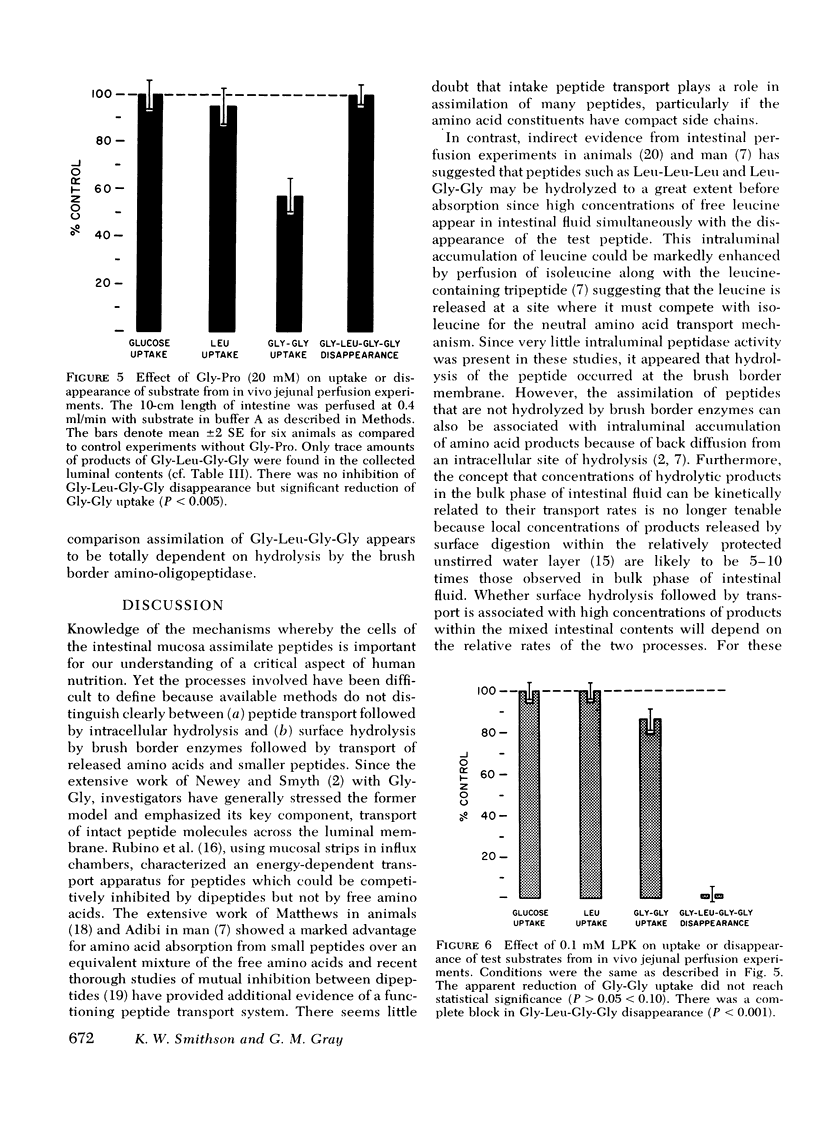

Gly-l-Pro (10 mM), a peptide known to be transported intact but not to be hydrolyzed by the brush border aminopeptidase, failed to inhibit Gly-l-Leu-Gly-Gly disappearance suggesting that the tetrapeptide does not utilize the known intact transport mechanism.

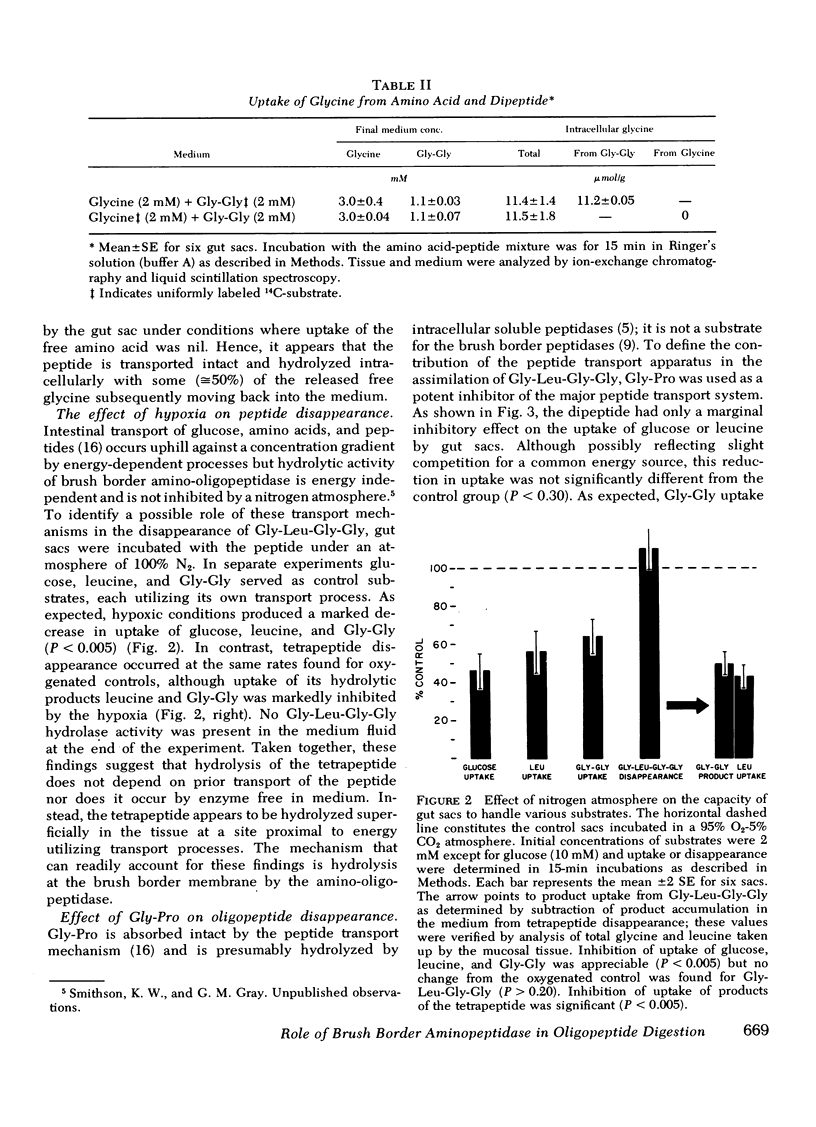

Hypoxic conditions (N2 atmosphere) in vitro markedly inhibited transport of glucose, leucine, and Gly-Gly but failed to impair Gly-l-Leu-Gly-Gly disappearance suggesting that the first step in assimilation of the tetrapeptide does not involve a transport process.

Disappearance of the tetrapeptide was completely blocked by l-leucyl-β-naphthylamide (10 mM), a specific substrate for brush border aminopeptidase and by the phthalimido derivative of l-leucine bromomethyl ketone, a potent peptidase inhibitor. Hence, the amino-oligopeptidase at the intestinal surface appears to be essential for the initial stages of assimilation of this model tetrapeptide.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adibi S. A. Intestinal transport of dipeptides in man: relative importance of hydrolysis and intact absorption. J Clin Invest. 1971 Nov;50(11):2266–2275. doi: 10.1172/JCI106724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adibi S. A., Morse E. L., Masilamani S. S., Amin P. M. Evidence for two different modes of tripeptide disappearance in human intestine. Uptake by peptide carrier systems and hydrolysis by peptide hydrolases. J Clin Invest. 1975 Dec;56(6):1355–1363. doi: 10.1172/JCI108215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvanitakis C., Ruhlen J., Folscroft J., Rhodes J. B. Digestion of tripeptides and disaccharides: relationship with brush border hydrolases. Am J Physiol. 1976 Jul;231(1):87–92. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.231.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asatoor A. M., Cheng B., Edwards K. D., Lant A. F., Matthews D. M., Milne M. D., Navab F., Richards A. J. Intestinal absorption of two dipeptides in Hartnup disease. Gut. 1970 May;11(5):380–387. doi: 10.1136/gut.11.5.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin K. A., Yamashiro K. M., Gray G. M. Human intestinal sucrase-isomaltase. Identification of free sucrase and isomaltase and cleavage of the hybrid into active distinct subunits. J Biol Chem. 1975 Aug 10;250(15):5735–5741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M., Radhakrishnan A. N. Glycyl-L-leucine hydrolase, a versatile 'master' dipeptidase from monkey small intestine. Biochem J. 1973 Dec;135(4):609–615. doi: 10.1042/bj1350609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das M., Radhakrishnan A. N. Studies on a wide-spectrum intestinal dipeptide uptake system in the monkey and in the human. Biochem J. 1975 Jan;146(1):133–139. doi: 10.1042/bj1460133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Femfert U., Cichocki P. Hydrophobic areas at the active site of aminopeptidase M. Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1974 Oct;355(10):1332–1334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heizer W. D., Kerley R. L., Isselbacher K. J. Intestinal peptide hydrolases differences between brush border and cytoplasmic enzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972 May 16;264(3):450–461. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(72)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettner C., Glover G. I., Prescott J. M. Kinetics of inhibition of Aeromonas aminopeptidase by leucine methyl ketone derivatives. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1974 Dec;165(2):739–743. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(74)90302-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews D. M., Craft I. L., Geddes D. M., Wise I. J., Hyde C. W. Absorption of glycine and glycine peptides from the small intestine of the rat. Clin Sci. 1968 Dec;35(3):415–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews D. M. Intestinal absorption of peptides. Physiol Rev. 1975 Oct;55(4):537–608. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1975.55.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEWEY H., SMYTH D. H. Cellular mechanisms in intestinal transfer of amino acids. J Physiol. 1962 Dec;164:527–551. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1962.sp007035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters T. J., MacMahon M. T. The absorption of glycine and glycine oligopeptides by the rat. Clin Sci. 1970 Dec;39(6):811–821. doi: 10.1042/cs0390811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes J. B., Eichholz A., Crane R. K. Studies on the organization of the brush border in intestinal epithelial cells. IV. Aminopeptidase activity in microvillus membranes of hamster intestinal brush borders. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1967;135(5):959–965. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(67)90065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubino A., Field M., Shwachman H. Intestinal transport of amino acid residues of dipeptides. I. Influx of the glycine residue of glycyl-L-proline across mucosal border. J Biol Chem. 1971 Jun 10;246(11):3542–3548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILSON T. H., WISEMAN G. The use of sacs of everted small intestine for the study of the transference of substances from the mucosal to the serosal surface. J Physiol. 1954 Jan;123(1):116–125. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1954.sp005036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson F. A., Dietschy J. M. The intestinal unstirred layer: its surface area and effect on active transport kinetics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1974 Aug 21;363(1):112–126. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(74)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojnarowska F., Gray G. M. Intestinal surface peptide hydrolases: identification and characterization of three enzymes from rat brush border. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975 Sep 22;403(1):147–160. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(75)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]