Abstract

This study investigated fast mapping in late-talking (LT) toddlers and toddlers with normal language (NL) development matched on age, nonverbal cognition, and maternal education. The fast mapping task included novel object labels and familiar words. The LT group performed significantly worse than the NL group on novel word comprehension and production, as well as familiar word production. For both groups, fast mapping performance was associated with concurrent language ability and later language outcomes. A post hoc analysis of phonotactic probability (PP) and neighborhood density (ND) suggested that the majority of NL toddlers displayed optimal learning of the nonword with low PP/ND. The LT group did not display the same sensitivity to PP/ND characteristics as the NL group.

Child language researchers have a long standing interest in investigating the mechanisms by which children are able to learn new words following only a limited amount of exposure. To empirically investigate the earliest stages of children’s novel word learning, researchers have commonly employed tasks of fast mapping ability. The process of lexical fast mapping refers to the incomplete, initial phase of word learning that occurs when a child is first exposed to an unknown word and its referent (Carey & Bartlett, 1978). Traditional fast mapping tasks have involved exposure to a new word or words, followed by comprehension and production probes used to track children’s learning. In this way, researchers have been able to investigate the quality and quantity of information that children retain after they are first exposed to a novel word.

Studies of fast mapping in typical populations have revealed that many young children are able to comprehend and produce new words after hearing them only once. Dollaghan (1985) found that when provided with one exposure to a novel word and its referent during a structured play activity, 81% of typically developing preschool children correctly comprehended the word and 45% of children accurately produced the novel word in subsequent probes. In addition to investigating the performance of typically developing children on fast mapping tasks, a number of studies in recent years have focused on the performance of children with language delays or disorders. Because these children follow a delayed course of language development, researchers have been interested in the ways in which they learn novel words compared to their typically developing peers.

A population of particular interest is toddlers who are late to talk compared to their peers with normal language around 24 months of age. Late-talking (LT) toddlers are those children who demonstrate delayed expressive language skills, typically indexed by a limited expressive vocabulary or limited two-word combinations relative to their peers. Research has shown that the majority of LT toddlers demonstrate language skills within the normal range by kindergarten on standardized tests, but that as a group they continue to score below normal language peers matched on socioeconomic status (SES) and nonverbal cognitive level (Ellis Weismer, 2007; Paul, 1996; Rescorla, 2002, 2009).

Importantly, late talker status is not an issue of clinical diagnosis. When children are identified as late to talk at an early age, they simply represent the lower end of the normal distribution in terms of their expressive language skills. However, those children who do not score within the normal range by preschool or early school age form a subgroup of children who may be diagnosed with specific language impairment (SLI). SLI involves the presence of a language disorder that is not attributable to other developmental disabilities, frank sensory or motor deficits, or acquired brain injury. Because LT toddlers are at risk for SLI, investigating their word learning abilities may provide information about the early bases for subsequent language learning problems. There is a lack of prior fast mapping research focused on LT toddlers, but there is a body of research that has examined fast mapping abilities in somewhat older children diagnosed with SLI.

Fast mapping in children with language delays or language impairment

To our knowledge, there are no prior investigations that have examined fast mapping in LT toddlers (though brief preliminary/overview findings for the current fast mapping study have been reported by Ellis Weismer and Evans (2002) and Ellis Weismer (2007) within descriptions of their larger longitudinal investigation of language development in late talkers). Despite the lack of fast mapping studies with LT toddlers, there are two studies that have explored related aspects of word learning in this population. Jones (2003) conducted an investigation of novel word extension in LT toddlers. In that study, LT toddlers (ages 2 to 3 years) were identified as those whose productive vocabulary fell at or below the 30th percentile on the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory: Words and Sentences (CDI; Fenson et al., 1993). Jones found that NL toddlers and LT toddlers did not differ significantly in the number of trials to criterion required to comprehend novel words based on the overall similarity of their referents. In contrast to the NL group, however, the LT group did not show the typical shape bias in word learning, such that the LTs did not consistently generalize a novel name to a referent of the same shape but instead tended to generalize novel names by texture similarity. This finding led Jones to conclude that shape bias may aid NL children in the early stages of novel word learning. Based on findings from another study, Jones and Smith (2005) concluded that LT children may have a broader deficit related to recognition of abstract shapes and that these children may not be learning lexical categories as “deeply” as the NL children.

A number of studies have investigated fast mapping in children with language impairment. Dollaghan (1987) investigated the production and comprehension of a single novel word (koob) in preschoolers with SLI and age-matched children with normal language (NL). The fast mapping task, which was presented in the context of a structured play activity with a puppet, involved an initial exposure to the novel word followed by a probe for comprehension and a probe for production. The NL and SLI groups showed no differences in comprehension accuracy, but significantly fewer children with SLI correctly produced the target word. Dollaghan interpreted these results as indicating that children with SLI may store adequate information about a new word to allow for successful comprehension but that they have deficits in storing and accessing phonological information that make production of new words more difficult.

Gray (2003, 2004) examined children’s fast mapping of two-syllable uncommon English words as part of an investigation of extended word learning in preschoolers with SLI and those with NL. Children were presented with four familiar words and four unfamiliar words in a task involving exposure, comprehension, and production phases. In both studies, children with SLI performed similarly to age-matched peers with NL on the production of the unfamiliar words after limited exposure. Comprehension findings were mixed, in that group differences were present in one study (2004) but not the other (2003). Even when comprehension accuracies were similar following limited exposure, differences emerged after several days of more protracted word learning (2003). These results were interpreted as suggesting that children with NL and SLI perform similarly when given limited exposures to a new word, but that the children with NL are able to demonstrate more robust learning when provided with explicit teaching and feedback over a longer period of time. Gray conducted two subsequent studies (2005, 2006) that revealed no differences in the fast mapping abilities of preschool children with and without SLI for all but 5-year-old age groups, which Gray suggested may have been explained by the more severe language deficit in the 5-year-old children (Gray, 2006).

Alt, Plante, and Creusere (2004) investigated the ways in which children with SLI (4-6 years old) fast map lexical labels and semantic features of novel objects and actions compared to their age-matched NL peers. A computer program presented children with nonword labels for 12 novel objects and 12 novel actions, which each had four associated features (e.g., color and pattern for objects, and sound and shape change for verbs). On both the identification of lexical labels and the recognition of semantic features, the SLI group performed significantly less accurately than their NL peers. Actions (verbs) were more difficult to fast map than object labels (nouns) for both groups. In a subsequent study, Alt and Plante (2006) replicated the finding that children with SLI have difficulty mapping lexical labels and semantic features of objects compared to their peers and concluded that children with SLI have a deficit not only at the level of the object label, but also at the conceptual level involved in encoding semantic features of novel objects. In this study half of the nonwords were composed of common sound sequences and half of uncommon sound sequences. Results indicated that in their responses to lexical label probes, children with NL appeared to be sensitive to the phonology of word labels, whereas the group of children with SLI did not demonstrate the same pattern of sensitivity.

In a series of naturalistic word learning studies, Rice and colleagues examined the ability of preschoolers with SLI to fast map new words without explicit exposure, prompting or instruction, a process described as quick incidental learning (QUIL; Rice, Buhr, & Nemeth, 1990; Rice, Buhr, & Oetting, 1992; Rice, Oetting, Marquis, Bode, & Pae, 1994). Children were exposed to uncommon English target words embedded in short, animated video clips and were subsequently probed for comprehension of the target words. In these studies, children with SLI showed some evidence of fast mapping comprehension but consistently performed similarly to a younger, MLU-matched group of children, significantly below the level of their NL peers. Rice and colleagues attributed the decreased comprehension in the SLI group to the task demands of the QUIL paradigm, which requires children to fast map novel words without an explicit exposure and clear association with a tangible referent. After ten exposures to the embedded target words, the children with SLI performed as well as their NL peers, something they were not able to do following three exposures (Rice et al., 1994). Rice et al. interpreted this finding as indicating that children with SLI require additional exposures of a new word to establish a more stable lexical representation, which then allows them to perform at a level equal to that of their NL peers.

Purpose of the current study

Vocabulary deficits are a hallmark of LT toddlers. Fast mapping abilities are posited to play a crucial role in word learning, yet prior research has not investigated fast mapping in late talkers. This is an important area of investigation because LT toddlers are at risk for SLI and the bulk of the evidence indicates that children with SLI exhibit deficits in fast mapping. Furthermore, since toddlers with a history of late onset of language development tend to have less proficient language abilities than their cognitive and SES matched peers through adolescence (even when they do not have a clinical language disorder), it would be informative to explore early language learning mechanisms and their association with later language abilities. This study investigated the comprehension and production performance of LT and NL toddlers on a fast mapping task and examined correlations between fast mapping and scores on other language measures, both concurrently and at a three-year follow-up assessment. We focused on two main questions: First, do late talking toddlers demonstrate limitations in comprehension or production on a fast mapping task compared to children with typically developing language? Second, is there a relationship between children’s performance on a fast mapping task and performance on other language measures, either concurrently or across time?

Methods

Participants

Thirty toddlers identified as late talkers (LT) and 32 toddlers with normal language (NL) development participated in this study. These children were part of a larger sample of childrenparticipating in a longitudinal investigation of specific language delay from age 2 years, 6 months, to age 5 years, 6 months. Approximately 40% of the participants in the present study were included in a report of preliminary findings for the fast mapping task (Ellis Weismer & Evans, 2002); there was approximately 80% overlap in participants for this study and a brief overview of fast mapping findings included within a chapter describing the larger longitudinal investigation (Ellis Weismer, 2007). In the current study we focused on children’s first visit when they were approximately 30 months of age, and their final visit when they were approximately 66 months of age. Participants were seen in a playroom assessment suite at the Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and were administered a variety of measures at both visits, as described below.

The MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory: Words and Sentences (CDI; Fenson et al., 1993) was completed by parents when toddlers were 24 months of age and was used to assess initial language status as indexed by productive vocabulary. The 10th percentile for total productive vocabulary was used as a cutpoint for the purposes of initially classifying children as late talkers (Ellis Weismer & Evans, 2002). This criterion for identification of late talkers also has been used in prior research (Ellis Weismer, Murray-Branch, & Miller, 1994; Thal, Bates, Goodman, & Jahn-Samilo, 1997; Thal & Tobias, 1992, 1994). Children in the NL group performed above the 20th percentile for productive vocabulary on the CDI at 24 months. Separate gender-based norms were used to classify boys and girls in relation to the 10th percentile cutoff, which allowed for developmental differences across gender. Parents completed the CDI a second time at the initial laboratory visit to obtain a current measure of vocabulary at 30 months of age. At that visit, children in the NL group performed above the 20th percentile and children in the LT group performed at or below the 15th percentile.

Each toddler identified as late to talk was matched with a toddler with typically developing language based on chronological age within one month, nonverbal cognition within two points on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development, Second Edition (BSID; Bayley, 1993), and socioeconomic status within two years of mother’s education. The additional two children in the NL group were matched to children in the LT group who already had one other match. The nonverbal items from the BSID were used to match the NL and LT groups on nonverbal cognitive abilities (see Rescorla, 2002, 2009; Spitz, Tallal, Flax, & Benasich, 1997). Maternal education level was used as an index of SES (Chapman, Schwartz, & Kay-Raining Bird, 1991). T-tests confirmed that the NL and LT groups did not differ significantly on mean chronological age, non-verbal cognition, or SES. The sex distribution was similar across groups, with males comprising at least two-thirds of the NL and LT groups. Both groups were comprised of mostly Caucasian children, with only a small number of children from other racial/ethnic backgrounds. Table 1 provides a summary of participant characteristics.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| NL (N=32) | LT (N=30) | |

|---|---|---|

| CA | ||

| M (SD) | 30.56 (0.76) | 30.40 (0.81) |

| Range | 30-33 | 29-33 |

| Bayley | ||

| M (SD) | 7.75 (1.14) | 7.17 (1.68) |

| Range | 5-10 | 4-10 |

| SES | ||

| M (SD) | 15.75 (1.81) | 15.28 (2.00) |

| Range | 12-19 | 12-19 |

| Gender | 24M / 8F | 20M / 10F |

| Heritage | 31 White/1 African American | 26 White/ 2 African American 1 Asian American |

Note. CA = chronological age in months; Bayley = nonverbal items from the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (Bayley, 1993); SES = socioeconomic status as indexed by number of years of maternal education.

Parents completed a background information form and brief developmental screening form. This information was used to determine that all toddlers were developing typically in areas other than language and that they came from monolingual English-speaking homes. Several measures were used to verify toddlers’ developmental status and perceptual/motor abilities at the 30-month evaluation. In order to be eligible to participate in the study, all toddlers were required to: 1) score within normal range on the Denver II (Frankenburg et al., 1990), a measure of general development; 2) exhibit normal hearing as assessed according to ASHA 1997 guidelines for pediatric hearing screening; and 3) demonstrate normal oral and speech motor abilities as evaluated by the pediatric clinical assessment tool developed by Robbins and Klee (1987).

Expressive and receptive language abilities were assessed at the initial 30-month visit by the Preschool Language Scale—Third Edition (PLS-3; Zimmerman, Steiner, & Pond, 1992). The PLS-3 assesses receptive and expressive language with the Auditory Comprehension (AC) subscale and Expressive Communication (EC) subscale, respectively. At the final visit, children were given the Test of Language Development-Primary, Third Edition (TOLD-P:3; Newcomber & Hammill, 1997). Based on their performance on several subtests of the TOLD-P:3, children were assigned a Listening Quotient for receptive language and a Speaking Quotient for expressive language.

A language sample was collected at both the initial and final visit. A minimum of ten minutes was collected within an examiner-child interaction using a standard set of toys in a free-play context. The samples were videotaped and were later transcribed using the Systematic Analysis of Language Transcripts (SALT; Miller & Chapman, 2002). Each child’s mean length of utterance (MLU) was calculated as a measure of the average number of morphemes per utterance in each child’s spontaneous speech.

The performance of both groups on all language measures is summarized in Table 2. The two groups exhibited non-overlapping numbers of words produced and percentile ranges on the CDI at both 24 months (when initially recruited) and at 30 months (when the fast mapping task was administered). T-tests confirmed that the mean performance on all language measures at 30 months was significantly different for the two groups. However, there was some overlap for individual children’s scores on overall measures of lexical and grammatical production (PLS EC and MLU). There was considerable overlap in PLS AC scores, which is not surprising given that late talkers typically have normal range receptive language or only mild comprehension delays.

Table 2.

Performance on language measures

| NL | LT | |

|---|---|---|

| CDI-WP (24 mo) | ||

| M (SD) | 393.19 (141.49) | 46.62 (27.77) |

| Range | 159-678 | 3-116 |

| CDI-Percentile (24 mo) | ||

| M (SD) | 0.65 (0.22) | 0.03 (0.04) |

| Range | 0.23-0.99 | 0.00-0.10 |

| CDI-WP (30 mo) | ||

| M (SD) | 572.55 (79.93) | 197.68 (85.85) |

| Range | 409-680 | 6-334 |

| CDI-Percentile (30 mo) | ||

| M (SD) | 0.63 (0.26) | 0.07 (0.05) |

| Range | 0.23-0.99 | 0.00-0.15 |

| PLS-3 AC (30 mo) | ||

| M (SD) | 123.59 (16.07) | 107.43 (20.53) |

| Range | 86-105 | 73-144 |

| PLS-3 EC (30 mo) | ||

| M (SD) | 116.63 (12.74) | 88.10 (8.68) |

| Range | 90-145 | 69-104 |

| MLU (30 mo) | ||

| M (SD) | 2.82 (0.56) | 1.68 (0.46) |

| Range | 1.36-3.90 | 1.07-3.33 |

| Listening Quotient (66 mo) | ||

| M (SD) | 124.55 (10.25) | 119.63 (12.03) |

| Range | 106-142 | 94-139 |

| Speaking Quotient (66 mo) | ||

| M (SD) | 113.14 (7.79) | 103.00 (11.94) |

| Range | 94-130 | 82-127 |

| MLU (66 mo) | ||

| M (SD) | 5.58 (1.78) | 5.24 (1.58) |

| Range | 2.36-8.91 | 2.13-7.83 |

Note. CDI-WP and CDI-Percentile = Communicative Development Inventory, number of words produced and percentile rank. PLS-3 AC and PLS-3 EC = Preschool Language Scale, Third Edition, Auditory Comprehension and Expressive Communication subscales. MLU = Mean length of utterance. Listening and Speaking Quotients are from the TOLD-P:3.

Procedure

Fast Mapping Task

The experimental task assessed the toddlers’ fast mapping abilities within a puppet play activity. Children were exposed to two novel words (koob and tade) and two familiar words (apple and cookie). The familiar words were included to maintain children’s interest in the task by allowing them to accurately name and identify common objects successfully. The novel words referred to two unusual plastic objects with low codability, similar to objects for which adult judges were unable to provide a single-word label in a prior novel word learning study (Ellis Weismer & Hesketh, 1996). Plastic toy replicas of two real food items were used as referents for the familiar words. Both of the novel words consisted of consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) monosyllables composed of early developing sounds typically present in the phonetic repertoire of 30-month-old toddlers (Stoel-Gammon, 1991). The novel words followed English phonotactic rules regarding allowable sound sequences.

The task was comprised of three trials, with each trial consisting of an exposure, production, and comprehension phase. Children initially were shown a toy puppet and instructed to help the puppet pack a picnic with “all kinds of things” to eat, including “silly things.” In order to teach children which words should be paired with a particular object, the examiner produced each word while showing the child its referent during the exposure phase. During the exposure phase, the examiner told the child, “Here’s a _. Put it in the basket.” Examiners were instructed not to repeat the target word during the exposure phase. Once all four objects (2 familiar and 2 novel) were labeled, the examiner proceeded to the testing phase of the task. During the testing phase, no feedback on identification or naming accuracy was provided. After the initial trial, the task again was carried out identically for the same puppet, and a third time with a different puppet, for a total of three trials.

Following each exposure phase, children were probed for production of the two novel words and two familiar words. The examiner picked up the target object and asked, “What’s this?” After completion of the production probes, two foil objects (i.e., two additional unusual plastic objects with low codability) were added to the picnic basket. After saying, “Let’s put some more things in too” and adding two foil novel objects, the examiner told the child which item the puppet wanted. She said, “He wants to taste them. Can you get the _?” Items were replaced in the basket after each comprehension probe, and the foil objects remained the same throughout the task. Children were not asked to choose either of the foil objects. During the comprehension probes children selected from among six objects (i.e., two familiar objects, 2 novel word referent objects, and 2 unnamed foil objects), such that overall chance performance was 1/6 or 17%. However, if it is assumed that children knew the names for the familiar objects and therefore would exclude them, the probability of choosing the correct novel object from the two target objects (koob and tade) and two foil objects during the comprehension phase was 1/4 or 25%. We observed that children in both groups incorrectly selected foil items on occasion, indicating that they were not restricting their choices only to the two named novel objects but instead were choosing among the four unusual objects.

Scoring

Comprehension accuracy was based on children’s correct selection of the target referent. Production accuracy for each novel word was based on children’s production of at least two phonemes (of three) in the appropriate sequence (Dollaghan, 1985, 1987; Ellis Weismer & Hesketh, 1993). For example, /ku/ would be scored as correct for /kub/. The decision to use the criterion of two out of three phonemes in the correct sequence was based on prior fast mapping and novel word learning research that had used this approach; by using the same criterion the production results of the current study could be compared to those studies. Furthermore, given the young age of the sample (M=30 mo) a number of children in both groups exhibited phonological processes such as final consonant deletion. We did not want to penalize children for applying routine immature phonological processes to their production of the new CVC nonwords by requiring exact adult production for a correct response. Note that the maximum score for production across the task was six for novel words or familiar words. Likewise, the highest possible score for comprehension was six for either novel or familiar words.

Reliability and Interrater Agreement

Production and comprehension accuracy data from four NL toddlers and three LT toddlers (11% of the sample) were randomly selected from each of the two groups and scored a second time by a different observer. Each judge could rate the response of a participant as correct, incorrect, or no response. Interrater agreement between the two examiners for production of novel words was 85.71%. Interrater agreement for comprehension of novel words and comprehension and production of familiar words was 100%. Cohen’s kappa (Cohen, 1960) was used to assess measurements of agreement that were not at 100%. The kappa value for production of novel words was .671, which is widely considered to indicate substantial agreement.

Procedural Reliability

All examiners were trained in administering the experimental task by watching videotapes of the procedure and by engaging in practice sessions with at least two toddlers who were not participants in the study. Additionally, we assessed fidelity to the experimental protocol/script. To measure procedural reliability, an individual with no previous knowledge of the experimental task watched three of the sessions completed with late talkers and four of the sessions completed with typically developing children, for an overall total of 7/62. A binary coding system was used, where a score of “1” meant the category in question had been completed according to the experimental script. A score of “0” was given for any variation from the script. The following categories were scored: examiner instructions for the exposure, production, and comprehension phases, and lack of feedback during the test trials.

Results of these analyses indicated that procedural reliability was at or above .90 for each of the above categories. The average score for “no feedback” across the 12 test trials was 1.0 (SD=0), indicating that examiners were successful 100% of the time in refraining from providing feedback for correct or incorrect responses. For the exposure and production phase, the average of scores was .989 (SD=.003), while the average of scores for the comprehension phase was .906 (SD=112). All instances of “0” scores were for multiple prompts given to the child. These usually occurred because the child was distracted or because parents repeated the prompts to their child.

Results

Group Differences

Our first research question related to group differences in comprehension and production accuracy on the fast mapping task. Due to the limited number of possible responses (two words across three trials, yielding a maximum score of six) and to the possibility of ceiling and/or floor effects, the familiar and novel data were examined for evidence of non-normality. Visual inspection of the data plotted against a normal curve suggested that familiar comprehension and production were positively skewed and that novel production was negatively skewed, while novel comprehension data approximated a normal distribution. To confirm visual inspection of the distributions, Kolgomorov-Smirnov tests were conducted to provide further information regarding the extent to which outcome data differed from a normal distribution. Familiar comprehension, familiar production, and novel production all differed significantly from the normal distribution (all ps=.00), while novel comprehension did not (p=.09). Because a majority of the variables did not meet the assumption of normally distributed outcome variables that is necessary to perform parametric tests, nonparametric analyses were used in all analyses.

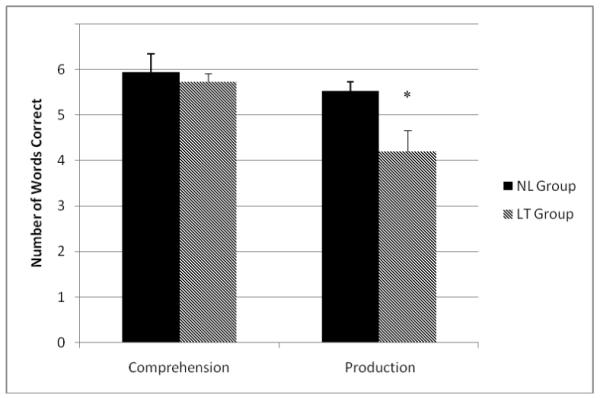

Mann-Whitney U tests were conducted to analyze group differences in familiar comprehension, familiar production, novel comprehension, and novel production. Familiar comprehension scores ranged from 5 to 6 for the NL group and 3 to 6 for the LT group. The mean rank for familiar comprehension in the NL group was 33.69 and the mean rank for the LT group was 29.17, a difference that was nonsignificant (Mann-Whitney U = 410.00, p = 0.09). Familiar production scores ranged from zero to six for both groups; the mean rank for the NL group was 36.50 and the mean rank for the LT group was 26.17, indicating a significant group difference (Mann-Whitney U = 320.00, p < .01). The NL group comprehended between one and six novel words and the LT group comprehended between zero and six novel words, and the NL and LT mean ranks were 37.56 and 25.03, respectively. The group difference for novel comprehension was significant, (Mann-Whitney U = 286.00, p<.01). Novel production scores ranged from zero to six for the NL group and from zero to four for the LT group. The mean rank of the NL group was 36.28 and the mean rank of the LT group was 26.40, indicating that the group difference in novel production was significant (Mann-Whitney U = 327.00, p<.001). In sum, the NL and LT groups demonstrated similar levels of performance only for familiar comprehension; the NL group outperformed the LT group on familiar production, novel comprehension, and novel production. Figure X presents a visual display of group performance on the fast mapping task. Although group differences were analyzed on the basis of mean ranks, means are presented in the figure for ease of interpretation.

Association between Fast Mapping Performance and Language Skills

We were also interested the relationship between children’s performance on the fast mapping task and their language abilities, both concurrently and across time. To address this question, we calculated Spearman Rank correlation coefficients between novel comprehension and production on the fast mapping task and several language measures at 30 months and at 66 months. Because we hypothesized that relationships may differ for the NL and LT groups, we conducted separate correlations for each group. We found that for the NL group, novel production was significantly associated with performance on the AC subscale of the PLS-3 at 30 months (ρ = .39, p<.05). As expected, the correlation between novel comprehension and novel production on the fast mapping task was significant (ρ = .66, p<.01). Novel production was not significantly correlated with the EC subscale of the PLS-3, number of words produced on the CDI, or MLU (all ps > 0.44), and no significant correlations involving novel comprehension were identified in the NL group (all ps > 0.10). For the LT group, a concurrent association was identified between novel word production and number of words produced on the CDI at 30 months (ρ = .44, p<.05). The association between novel comprehension and novel production for the LT group approached, but did not reach, statistical significance (p=.054). Novel word production was not significantly associated with either subscale of the PLS-3 or MLU (all ps > .16), and no significant correlations involving novel comprehension were identified in the LT group (all ps>.09).

Next, we examined the relationship between novel comprehension and production, and language outcomes at 66 months. In the NL group, novel production at 30 months was significantly correlated with the Listening Quotient on the TOLD-P:3 at 66 months (ρ = .44, p<.01). Novel production was not significantly associated with the Speaking Quotient on the TOLD-P:3 or MLU (all ps > .15), and no significant correlations involving novel comprehension were identified in the NL group (all ps > .21). In the LT group, novel comprehension was significantly correlated with the Listening Quotient on the TOLD-P:3 (ρ = .43, p<.01). Novel comprehension was not significantly associated with the Speaking Quotient on the TOLD-P:3 or MLU (all ps > .51), and no significant associations were identified involving novel production in the LT group(all ps > .71). It is interesting to note that vocabulary abilities at 30 months as measured by the CDI were not significantly correlated with outcomes on the TOLD-P:3 at 66 months for either group (all ps>.33).

Effects of Novel Word Composition: A Post Hoc Analysis

Although the phonotactic characteristics of the novel words koob and tade were not manipulated a priori, a post hoc analysis revealed that they differed in terms of their phonotactic probability (PP) and neighborhood density (ND). Phonotactic probability (PP) refers to the frequency with which sound sequences occur in specific word positions; words with high PP consist of phonemes and phoneme sequences that are common in a particular language. Neighborhood density (ND) refers to the number of words that differ from a target word by adding, substituting, or deleting a single phoneme; words with high ND have many close neighbors (sat: cat, at, spat, sit, site, sad, sack), whereas those with low ND have few neighbors (beige). Research has shown that PP and ND influence children’s word learning in both natural (Storkel, 2009) and experimental settings (Hoover, Storkel, & Hogan, 2010; Storkel, 2001; Storkel and Rogers, 2000). Therefore, this task provided a valuable opportunity to examine the effects of these characteristics on the fast mapping performance of LT toddlers, which has not been investigated previously.

The phonotactic probability (PP) of the two novel words was calculated using the MHR database (Moe, Hopkins, & Rush, 1982). The MHR database consists of a list of pronunciations of 6,366 most frequently occurring words in the spontaneous speech of first grade children (see Edwards, Beckman, & Munson, 2004 for more details). Based on biphone type and token probabilities in the MHR database, koob has an overall type probability of −12.7 and a token probability of −15.5, whereas tade has a type probability of −9.9 and a token probability of −11.6. Note that these probabilities are expressed as natural logarithms; they indicate that koob is less probable than tade, due in large part to the low probability of the /ub/ sequence. The nonword tade has 11 phonological neighbors in the MHR database – laid, made, stayed, tail, take, tape, Ted, toad, Todd, trade, and wade – such that the sum of their individual frequencies is 824 occurrences. On the other hand, koob has 4 neighbors – coo, cool, cub, and tube – and the sum of their individual frequencies is 18 occurrences. This indicates that tade has many more neighbors than koob, with nearly a 3:1 ratio for raw neighborhood density and nearly a 46:1 ratio for neighborhood frequency. Since PP and ND were correlated (i.e., tade had high PP and ND, and koob had low PP and ND), we examined the effects of these related characteristics together; in other words, it is beyond the scope of the present study to tease apart the independent effects of PP and ND.

To explore the effects of PP/ND on fast mapping performance, we examined the accuracy levels for each word—tade, which had a high PP/ND, and koob, which had a low PP/ND. Because the comprehension condition yielded greater variability in performance as opposed to production which resulted in low performance by both groups, we focused on the effects of PP/ND on comprehension of the novel words. In the NL group, 56% of children showed a low PP/ND advantage, compared to 25% who showed a high PP/ND advantage and 19% who showed no advantage for either word. In the LT group, 30% of children demonstrated a low PP/ND advantage, compared to 23% who showed a high PP/ND advantage and 47% showed no advantage for either word. A multiplicative binomial test of group proportions revealed that significantly more children in the NL group than the LT group demonstrated a low PP/ND advantage (χ2 = 4.34, p<.05).

Next, we were interested in whether LT children who showed a low PP/ND advantage demonstrated better performance than LT children who did not show that advantage (i.e., showing no advantage or showing a high PP/ND advantage). We hypothesized that the LT toddlers who demonstrated the low PP/ND advantage, similar to the majority of children with NL, might outperform those LT toddlers who did not show that same advantage on various language measures. At 30 months, 9 LTs had a low PP/ND advantage and 21 did not. A Mann-Whitney U test revealed that LT toddlers with a low PP/ND advantage (mean rank = 20.39) scored significantly higher on the PLS-3 AC subscale than the LTs who did not show a low PP/ND advantage (mean rank = 13.40; Mann-Whitney U = 50.50, p<.05). The two LT groups did not differ for concurrent performance on the CDI, MLU, or the EC subscale of the PLS-3 (all ps > .10). At 66 months, LT toddlers with a low PP/ND advantage had significantly higher MLUs than those who did not demonstrate that advantage (Mann-Whitney U = 26.50, p<.05). The mean ranks for MLU were 16.21 for the low PP/ND advantage group and 10.16 for the LTs who did not show that advantage. LT toddlers with a low PP/ND advantage also outperformed those LT toddlers not showing the advantage on the Speaking Quotient of the TOLD-P:3 (Mann-Whitney U = 27.00, p<.04, low PP/ND mean rank = 17.14, non-low PP/ND mean rank = 10.59). There were no group differences for LTs with and without low PP/ND advantages for the Listening Quotient of the TOLD-P:3 (p=.15).

Discussion

Group Differences

The results of the present study indicated that children who were initially identified as late to talk at 24 months of age performed significantly below the level of their normal language peers (matched on age, nonverbal cognition, and SES) on a fast mapping task at 30 months. Overall findings from the fast mapping task revealed that the LT group comprehended significantly fewer novel words than those in the NL group, though the LT group was not significantly poorer than the NL group in comprehending familiar words. The NL group outperformed the LT group on production of novel words as well as familiar words. As expected, both groups of children were more adept at comprehending novel words than producing them.

Considering that LT toddlers are identified on the basis of their limited expressive language, our finding of decreased production abilities for both familiar and novel words was not unexpected. The finding of decreased novel word production in the LT group suggests that they not only show limited expression of previously acquired words, but that they also have difficulties with fast mapping processes involved in the initial stages of word learning. At first glance it may seem surprising that the LT group also comprehended significantly fewer novel words than the NL group – in addition to exhibiting decreased production – because their comprehension level was within age level expectations on standardized measures and there was not a significant group difference for familiar word comprehension on the fast mapping task. Upon further consideration, however, it is apparent that the LT group was not as proficient as the NL group in comprehension of familiar words as evidenced by the significant group difference on the auditory comprehension scale of the PLS-3 at 30 months (even though both groups scored within normal range) and by the fact that group differences in familiar word comprehension approached significance (p=.09) on the fast mapping task. Taken together, these results suggest that late talkers’ limitations in expressive language do not just stem from lexical retrieval problems, but appear to be related to more fragile phonological, lexical and semantic representations that are reflected in subtle comprehension difficulties that, in turn, result in more substantive deficits in vocabulary production.

The finding of decreased comprehension and production of novel words by LT toddlers compared to children with NL is consistent with the results of several previous studies of children with SLI. Alt and Plante (2006) and Alt et al. (2004) found that children with SLI identified fewer lexical labels and recognized fewer semantic features than children with NL in a fast mapping task. Using an incidental fast mapping paradigm, Rice and colleagues (1990, 1992, 1994) found that children with SLI comprehended novel words less accurately than their NL peers and performed similarly to younger, MLU-matched children. Rice and colleagues hypothesized that poor performance of children with SLI might be due to the increased challenge of incidental fast mapping, but the current finding of decreased comprehension is consistent with findings from the QUIL tasks despite the explicit nature of the task and the limited number of words to which the children were exposed.

Although our results are consistent with the majority of previous findings of fast mapping in SLI, there are several studies that do not align completely with the current results. Dollaghan’s (1987) investigation of fast mapping skills revealed that when preschool children with SLI were provided with one exposure to a single novel word, they correctly produced that novel word less often than NL children but there were no group differences in comprehension. In the current study, we found group differences in both comprehension and production after three exposures to two novel words. Results from the series of word learning studies by Gray (2003, 2004, 2005, 2006) showed that in some tasks, children with NL and SLI do not differ in terms of fast mapping abilities with respect to either comprehension or production. Exceptions to this general finding consisted of comprehension group effects in one study (Gray, 2004) and both production and comprehension differences for the 5-year-old age group in two other studies (Gray 2005, 2006). It is important to keep in mind that in addition to focusing on SLI rather than LT toddlers, these prior investigations also differed from the present study along a number of methodological dimensions which may have played a role in the different findings.

Association between Fast Mapping and Language Abilities

Performance on the fast mapping task was associated with children’s performance on select concurrent and subsequent language measures. In the NL group there was a significant concurrent association between novel production and scores on the PLS-3 AC subscale at 30 months, as well as between novel word production and the Listening Quotient of the TOLD-P:3 at 66 months. In the LT group novel production was significantly correlated with number of words produced on the CDI at 30 months, and novel comprehension was correlated with the Listening Quotient on the TOLD-P:3 at 66 months. It is noteworthy that performance on such a short and seemingly simple task showed an association with standardized receptive language scores for both groups, and with productive vocabulary for the LT group. For the NL group significant associations involved cross-domain associations (novel production – language comprehension) whereas only within-domain associations were observed for the LT group (novel word production – language production at 30 months and novel word comprehension – language comprehension at 66 months). In the case of the LT group, the size of their current productive vocabulary as measured by parental report was correlated with their ability to produce novel words. This finding appears to be consistent with the phonological sensitivity hypothesis proposed by Edwards and colleagues (2004) in that late talkers’ restricted vocabulary and difficulties in learning new words may stem from less robust phonological representations that are formed as a result of their smaller vocabularies and more limited speech production experience (e.g., Stoel-Gammon, 1989).

Effects of Novel Word Characteristics

We examined, in a post hoc fashion, how phonotactic probability and neighborhood density of the novel stimuli affected nonword learning. The majority of children in the NL group demonstrated a fast mapping advantage for the low PP/ND nonword (koob) on the comprehension phase of the fast mapping task, whereas almost half of the LT group showed no advantage for either the low PP/ND or the high PP/ND nonword (tade). Thus, a significantly higher proportion of the children in the NL group displayed a clear low PP/ND advantage for fast mapping of novel words than in the LT group. Results of a study by Alt and Plante (2006) suggested that children with SLI might not show the same sensitivity or awareness of the phonological composition of words that NL children show. Similarly, the current findings suggest that LTs, as a group, demonstrated less sensitivity to PP/ND cues than did their peers with typical language development.

Our exploration of children’s sensitivity to the PP and ND of the novel words also helped to shed light on the issue of language outcomes for LT toddlers. Because a majority of NL toddlers showed a low PP/ND advantage in novel word learning, we were interested in the subset of LT toddlers who also displayed this advantage. We found that LT toddlers who demonstrated a low PP/ND advantage for novel word comprehension had higher PLS-3 AC scores at 30 months, and higher MLUs and Speaking Quotients on the TOLD-P:3 at 66 months than LT toddlers who did not exhibit this pattern of word learning. Although the vast majority of the children in the LT group performed within the normal range on the TOLD-P:3 by 66 months, late talkers as a group display less proficient language abilities than their cognitive and SES matched peers (Ellis Weismer, 2007; Rescorla, 2009). Fast mapping tasks may be useful in providing information about subtle language learning difficulties that could reflect later inefficiencies in language processing.

Recall that PP and ND are highly correlated but distinct word form characteristics, though they were not manipulated independently in the present study. Results from the current study indicated that the NL group displayed a learning advantage for the nonword with low PP/ND, which is generally consistent with recent findings for typically developing infants and young children (Hoover et al., 2010; Storkel, 2009). Strokel (2009) found that 16- to 30-month-old infants learned known vocabulary words with low PP earlier than words with high PP as indexed by parental report from the CDI. In addition to the low PP advantage that was found, children also learned words with high ND earlier than those with low ND. Results from two studies conducted by Hoover et al. (2010) revealed that preschool children’s learning of novel words within story contexts was facilitated by a convergence of word form characteristics, such that young children learned nonwords with low PP and low ND better than nonwords with high PP and low ND. These investigators concluded that – in contrast to adult word learning (Strokel, Armbrüster, & Hogan, 2006) – a convergence of low PP and low ND is optimal to trigger word learning in young children. When a nonword has low PP it is more salient because of the uniqueness of the sound combinations while low ND activates fewer existing lexical representations; together, these form characteristics are assumed to signal that the word is novel and trigger faster word learning. In the present study, the majority of NL toddlers appeared to follow this pattern, whereas the LT toddlers did not display a dominant pattern of sensitivity to PP and ND characteristics.

Limitations and Future Directions

A limitation of the current study is that the fast mapping task included only two novel words. Because we did not systematically manipulate PP/ND and had only one novel word of each type (high vs. low PP/ND), our ability to draw broader conclusions about the effect of these variables on young children’s novel word learning was limited to post hoc analysis of these particular form characteristics of the words. Although inclusion of multiple words may have been preferable, it is important to note that this study investigated fast mapping in young toddlers whose working memory skills limit the amount of information they are able to store and access in a short period of time. Pilot testing indicated that asking 30-month-old LT children to fast map more than two novel words within the context of the present task resulted in floor effects, which guided our decision to use two novel exemplars in the current study. Even though the number of novel words was restricted, the young children in both the NL and LT groups demonstrated low performance on the production phase of this fast mapping task. Children’s low accuracies limited the variability in production performance and may therefore have obscured findings that might have been detected on a more sensitive measure of fast mapping production.

Additional studies are needed to investigate the performance of LT toddlers on fast mapping and extended word-learning tasks to further characterize the nature of word-learning deficits in this population. Studies that manipulate PP and ND independently across a series of nonwords could help to uncover where the breakdown in word learning is occurring for late talkers. Based on recent investigations that have differentiated PP and ND, Storkel and colleagues (Hoover et al., 2010; Storkel, 2009; Storkel et al,, 2006) have espoused a model of word learning based on Gaskell and Dumay (2003) in which three processes are identified as critical for word learning. The first process, which initiates word learning, consists of the recognition that the word is novel. Second, a representation of the novel word is formed. In the third process the newly formed representation is integrated with existing representations. According to this view, PP is hypothesized to trigger the initial learning of novel words while ND to thought to affect integration of representations. Further investigation is needed to identify which of these processes are deficient in late talkers.

Future investigations are warranted to explore the nature and extent of differences in word learning by children who are late to talk and to further examine whether having early limitations in fast mapping is predictive of later language abilities. The ability to identify which LT toddlers will later be diagnosed with SLI continues to be a perplexing problem. Considering the difficulties that the LT group demonstrated on the fast mapping task in the present study and the finding that fast mapping performance was correlated with language comprehension scores three years later, it may be worthwhile to consider whether fast mapping abilities might help to inform diagnostic and prognostic decisions concerning these children. Other investigators have similarly suggested that processing-based measures such as fast mapping tasks might be useful in discerning whether children - particularly those from culturally or linguistically diverse backgrounds - are developing language typically. Johnson and deVilliers (2009) reported that performance on a fast mapping verb task was helpful in distinguishing school-age children with language impairment from those with typical language. These researchers argued that, in conjunction with a traditional test of acquired vocabulary, their fast mapping task provided information about whether delayed vocabulary might be related to limited exposure to new words, syntactic difficulties, or overall word learning difficulties based in a true language delay or disorder. For younger children, less complex noun and verb fast mapping tasks might perform a similar function in assisting with the identification of children who are at risk for persistent language learning difficulties. That is, these types of dynamic language measures may be useful in ascertaining children’s language learning facility as a supplement to information derived from standard measures of extant language knowledge.

Figure 1.

Familiar word accuracy. * Indicates a significant group difference at p<.05

Figure 2.

Novel word accuracy. * Indicates a significant group difference at p<.05.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this research was provided by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant 5R01 DC03731, “Linguistic Processing in Specific Language Delay” (S. Ellis-Weismer, PI, J.L. Evans & R.S. Chapman, Co-PIs) and support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development P30 core grant awarded to the Waisman Center. Support for the second author was provided by a T32 Training Grant T32 DC05359-06, “Interdisciplinary Research Training in Speech-Language Disorders” (S. Ellis-Weismer, PI & G. Weismer, Co-PI). Special thanks is extended to all the children and families who made this research possible. We would like to thank Benjamin Munson for his assistance in phonotactic probability and neighborhood density calculations. We would also like to acknowledge the work of the students in the Language Processes Laboratory at the Waisman Center who assisted with transcription and reliability.

References

- Alt M, Plante E. Factors that influence lexical and semantic fast mapping of young children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2006;49:941–954. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/068). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alt M, Plante E, Creusere M. Semantic features in fast-mapping: Performance of preschoolers with specific language impairment versus preschoolers with normal language. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:407–420. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/033). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N. Bayley scales of infant de velopment. 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Carey S, Bartlett E. Acquiring a single new word. Papers and Reports on Child Language Development. 1978;15:17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1960;20(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman RS, Schwartz SE, Kay-Raining Bird E. Language skill of children and adolescents with Down Syndrome: I. Comprehension. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1991;34:1106–1120. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3405.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollaghan C. Child meets word: ‘Fast mapping’ in preschool children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1985;28:449–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollaghan CA. Fast mapping in normal and language-impaired children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1987;52:218–222. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5203.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J, Beckman ME, Munson B. The interaction between vocabulary size and phonotactic probability effects on children’s production accuracy and fluency in nonword repetition. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:421–436. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/034). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Weismer S. Typical talkers, late talkers, and children with specific language impairment: A language endowment spectrum? In: Paul R, editor. Language disorders and development from a developmental perspective: Essays in honor of Robin S. Chapman. 2007. pp. 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Weismer S, Evans JL. The role of processing limitations in early identification of specific language impairment. Topics in Language Disorders. 2002;22:15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Weismer S, Hesketh LJ. The influence of prosodic and gestural cues on novel word acquisition by children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1993;36:1013–1025. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3605.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Weismer S, Hesketh LJ. Lexical learning by children with specific language impairment: Effects of linguistic input presented at varying speaking rates. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1996;39:177–190. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3901.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Weismer S, Murray-Branch J, Miller J. A prospective longitudinal study of language development in late talkers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1994;37:852–867. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3704.852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Resznick S, Thal D, Bates E, Hartung J, Pethick S, Reilly J. The MacArthur Communicative Developmental Inventory. Singular Publishing Group; San Diego, CA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Frankenburg W, Dodds J, Archer P, Bresnick B, Maschka P, Edelman N, et al. Denver Screening Test II. Denver Developmental Materials; Denver, CO: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gaskell MG, Dumay N. Lexical competition and the acquisition of novel words. Cognition. 2003;89:105–132. doi: 10.1016/s0010-0277(03)00070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. Word-learning by preschoolers with specific language impairment: What predicts success? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2003;46:56–67. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2003/005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. Word learning by preschoolers with specific language impairment: Predictors and poor learners. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:1117–1132. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/083). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. Word learning by preschoolers with specific language impairment: Effect of phonological or semantic cues. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2005;48:1452–1467. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/101). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray S. The relationship between phonological memory, receptive vocabulary, and fast mapping in young children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2006;49:955–969. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/069). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoover J, Storkel H, Hogan T. A cross-sectional comparison of the effects of phonotactic probability and neighborhood density on word learning by preschool children. Journal of Memory and Language. 2010;63:100–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JF, Chapman RS. SALT: Systematic analysis of language transcripts [Computer software] University of Wisconsin—Madison, Waisman Center, Language Analysis Laboratory; Madison: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Moe S, Hopkins M, Rush L. A vocabulary of first-grade children. Charles C. Thomas; Springfield, IL: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer PL, Hammill DD. Test of Language Development-Primary. Third Edition Pro-Ed., Inc.; Austin, TX: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VE, deVilliers JG. Syntactic frames in fast mapping verbs: effect of age, dialect, and clinical status. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52:610–622. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0135). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SS. Late talkers show no shape bias in a novel name extension task. Developmental Science. 2003;6:477–483. [Google Scholar]

- Jones SS, Smith LB. Object name learning and object perception: A deficit in late talkers. Journal of Child Language. 2005;32:223–240. doi: 10.1017/s0305000904006646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R. Clinical implications of the natural history of slow expressive language development. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 1996;5:5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L. Language and reading outcomes to age 9 in late-talking toddlers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002;45:360–371. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2002/028). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla L. Age 17 language and reading outcomes in late-talking toddlers: Support for a dimensional perspective on language delay. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009;52:16–30. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2008/07-0171). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ML, Buhr JC, Nemeth M. Fast mapping word-learning abilities of language-delayed preschoolers. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1990;55:33–42. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5501.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ML, Buhr JC, Oetting JB. Specific-language-impaired children’s quick incidental learning of words: The effect of a pause. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1992;35:1040–1048. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3505.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice ML, Oetting JB, Marquis J, Bode J, Pae S. Frequency of input effects on word comprehension of children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1994;37:106–122. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3701.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins J, Klee T. Clinical assessment of oropharyngeal motor development in young children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1987;52:271–277. doi: 10.1044/jshd.5203.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitz RV, Tallal P, Flax J, Benasich AA. Look who’s talking: A prospective study of familial transmission of language impairments. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1997;40:990–1001. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4005.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoel-Gammon C. Prespeech and early speech development of two late talkers. First Language. 1989;9:207–224. [Google Scholar]

- Stoel-Gammon C. Normal and disordered phonology in two-year-olds. Topics in Language Disorders. 1991;11:21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Storkel HL. Learning new words: Phonotactic probability in language development. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2001;44:1321–1337. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2001/103). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storkel HL. Developmental differences in the effects of phonological, lexical and semantic variables on word learning by infants. Journal of Child Language. 2009;36:291–321. doi: 10.1017/S030500090800891X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storkel HL, Armbrüster J, Hogan TP. Differentiating phonotactic probability and neighborhood density in adult word learning. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2006;49:1175–1192. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/085). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storkel HL, Rogers MA. The effect of probabilistic phonotactics on lexical acquisition. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 2000;14:407–425. [Google Scholar]

- Thal DJ, Bates E, Goodman J, Jahn-Samilo J. Continuity of language abilities: A exploratory study of late- and early-talking toddlers. Developmental Neuropsychology. 1997;13:239–273. [Google Scholar]

- Thal D, Tobias S. Communicative gestures in children with delayed onset of oral expressive vocabulary. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1992;35:1281–1289. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3506.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thal D, Tobias S. Relationships between language and gesture in normally developing and late-talking toddlers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1994;37:157–170. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3701.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman I, Steiner V, Pond R. Preschool Language Scale-3. Psychological Corporation; Chicago, IL: 1992. [Google Scholar]