Abstract

Objective

Although exposure to potentially traumatic experiences (PTEs) is common among US youths, information on posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) risk associated with PTEs is limited. We estimate lifetime prevalence of exposure to PTEs and PTSD, PTE-specific risk of PTSD, and associations of sociodemographics and temporally-prior DSM-IV disorders with PTE exposure, PTSD given exposure, and PTSD recovery among US adolescents.

Method

Data were drawn from 6,483 adolescent–parent pairs in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A), a national survey of adolescents aged 13–17. Lifetime exposure to interpersonal violence, accidents/injuries, network/witnessing, and other PTEs was assessed along with DSM-IV PTSD and other distress, fear, behavior, and substance disorders.

Results

A majority (61.8%) of adolescents experienced a lifetime PTE. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV PTSD was 4.7% and was significantly higher among females (7.3%) than males (2.2%). Exposure to PTEs, particularly interpersonal violence, was highest among adolescents not living with both biological parents and with pre-existing behavior disorders. Conditional probability of PTSD was highest for PTEs involving interpersonal violence. Predictors of PTSD among PTE-exposed adolescents included female gender, prior PTE exposure, and pre-existing fear and distress disorders. One-third (33.0%) of adolescents with lifetime PTSD continued to meet criteria within 30 days of interview. Poverty, U.S. nativity, bipolar disorder, and PTE exposure occurring after the focal trauma predicted nonrecovery.

Conclusions

Interventions designed to prevent PTSD in PTE-exposed youths should be targeted at victims of interpersonal violence with pre-existing fear and distress disorders, whereas interventions designed to reduce PTSD chronicity should attempt to prevent secondary PTE exposure.

Keywords: adolescent, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), trauma, violence

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiological data show that adolescence is the developmental period of highest risk of exposure to many types of potentially traumatic events (PTEs), including interpersonal violence, accidents, injuries, and numerous traumatic network events (i.e., PTEs occurring to loved ones).1–3 Public health efforts to prevent adolescent traumatic event (TE) exposure require accurate risk factor data. National surveys have examined sociodemographic variation in exposure to child-adolescent PTEs involving interpersonal violence,2,4 and basic correlates of other child-adolescent PTEs have been reported in community studies.5–8 These studies indicate that PTE exposure varies by basic sociodemographics (e.g., age, sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status),2,4,7–9 although most studies have examined a relatively narrow range of both risk factors and PTEs. Recent evidence from 2 cohort studies suggests that externalizing, but not internalizing, psychopathology also predicts child-adolescent PTE exposure, particularly interpersonal violence,10,11 although neither study was based on a broadly representative sample.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can develop following PTE exposure.12 PTSD is associated with substantial role impairment and heightened risk of secondary mental and physical disorders.13,14 Although numerous studies have examined youth PTSD in relation to specific types of PTEs, no data exist on the associations of a full range of sociodemographic factors, PTE characteristics, and prior psychopathology with PTSD risk in a U.S. national sample of youths. It is consequently unknown whether PTSD prevalence, distribution, and vulnerability factors follow the same population patterns among youths as adults. Although useful data on PTSD risk factors exist in focused studies of youths exposed to specific types of PTEs, like natural disaster,15 terrorism,16 and war,17 methodological differences across studies make comparisons across different types of PTEs difficult. Community studies have produced mixed findings regarding risk factors for PTSD in youths, with both sociodemographics and pre-existing mental disorders only inconsistently associated with PTSD. For example, after controlling for TEs some studies find higher PTSD risk for females than males8,9 and others no gender difference.6 Among youths exposed to PTEs, heightened PTSD risk has inconsistently been linked to prior externalizing10 and internalizing11 disorders.

Roughly 50% of cases of PTSD become chronic and persist for many years.18,19 Much of the public health burden of PTSD is consequently associated with chronic cases, highlighting the importance of identifying predictors of chronic course. However, we are aware of only one population-based study examining patterns and predictors of PTSD persistence among youths.19

The current report uses data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A), a population-based sample of U.S. adolescents, to describe the epidemiology of PTE exposure and PTSD among youths, including prevalence and correlates of PTE exposure, variation in conditional probability of PTSD given PTE exposure, and PTSD recovery. The predictors considered here include type of PTE, sociodemographics, and temporally prior mental disorders.

METHOD

Sample

As described in more detail elsewhere,20,21 the NCS-A was based on a national dual-frame household and school sample of adolescents ages 13–17. Face-to-face interviews were administered to adolescents and self-administered questionnaires (SAQs) to 1 parent or guardian of each adolescent. Data were collected between February 2001 and January 2004. Written informed consent was obtained from parents before approaching adolescents. Written adolescent assent was then obtained before surveying either adolescents or parents. Both adolescents and parents were paid $50 for participation. Recruitment and consent procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan.

The NCS-A household sample included adolescents recruited from households that participated in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R), a national household survey of adult mental disorders.22 A total of 879 school-attending adolescents participated in the household survey, with a conditional (on adult NCS-R participation, which had a 72.6% response rate) response rate of 86.8%. An additional 9,244 adolescents were recruited from a representative sample of schools in NCS-R sample areas. The adolescent response rate in the school sample (conditional on school participation) was 82.6%. Although the proportion of initially selected schools that participated in the NCS-A was low (28.0%), replacement schools were carefully matched to the original schools. Comparison of household sample respondents from nonparticipating schools with school sample respondents from replacement schools found no evidence of bias in estimates of either prevalence or correlates of mental disorders.20 The total NCS-A sample, combining household and school samples, included 10,123 adolescents.

The conditional (on adolescent response) response rate of the parent SAQ, which asked about developmental history and mental health of the participating adolescent, was 82.5–83.7% in the household-school samples. The 8,470 parents who completed SAQs included 6,483 who completed the long-form (which took approximately 1 hour to complete) and 1,987 the short-form (which took approximately 30 minutes to complete). An initial attempt was made to obtain a long-form SAQ from all participating parents. The short-form was obtained, often by telephone, only when it was not possible to obtain the long-form SAQ.

The current report focuses on the 6,483 adolescent–parent pairs for whom data were available from both adolescent interviews and long-form SAQs. Cases were weighted for variation in within-household probability of selection in the household sample and then separately in the household and school samples for differential nonresponse based on available data about non-respondents as well as for residual discrepancies between sample and population sociodemographic and geographic distributions. Sociodemographic information on the NCS-A sample is provided in Table S1, available online. The weighted household and school samples were merged with sums of weights proportional to relative sample sizes adjusted for design effects in estimating disorder prevalence. These weighting procedures are detailed elsewhere.20 The weighted sociodemographic distributions of the composite sample closely approximate those of the Census population.21

Measures

Diagnostic Assessment

Adolescents were administered a modified version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), a fully-structured interview administered by trained lay interviewers that assesses lifetime and past-year DSM-IV disorders.23 CIDI PTSD assessment began with questions about lifetime exposure to 19 PTEs that qualify for the DSM-IV A1 criterion, including 9 types of interpersonal violence (e.g., physical abuse by caregiver, rape, kidnapping by stranger or caregiver), 5 types of accidents (e.g., automobile accident, man-made or natural disaster), 3 types of network and witnessing events (unexpected death of loved one, witnessing death or serious injury), and 2 open-ended questions about other PTEs not explicitly included in the list as well as about PTEs that respondents did not want to describe concretely. (See Table 1 for all PTE categories.) Additional questions asked about age at first exposure and number of lifetime occurrences of each endorsed PTE.

Table 1.

Prevalence of Exposure to Potentially Traumatic Experiences (PTEs) and of DSM-IV/CIDI Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) (n=6,483).

| Lifetime PTE exposurea | Proportion of times the PTE was chosen as worst among those exposedb | Risk of lifetime PTSD among all those exposed to the PTEc | Lifetime PTSD among all who chose the PTE as worstd | 30-day PTSD among lifetime casese | 30-day PTSD among lifetime cases who chose the PTE as worstf | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Any PTE | 61.8 | (0.9) | 100.0 | (0.0) | 7.6 | (0.6) | 7.6 | (0.6) | 33.0 | (4.6) | 33.0 | (4.6) |

| PTE type | ||||||||||||

| I. Interpersonal violence | ||||||||||||

| Kidnapped | 0.6 | (0.2) | 13.7 | (5.7) | 37.0 | (13.5) | — | —g | — | —g | — | —g |

| Physical abuse by caregiver | 2.0 | (0.3) | 39.3 | (8.1) | 25.2 | (6.0) | 31.0 | (9.8) | 45.8 | (14.8) | 53.6 | (25.8) |

| Physical assault by romantic partner | 1.3 | (0.4) | — | —g | 29.1 | (12.5) | — | —g | 30.2 | (12.2) | — | —g |

| Other physical assault | 5.2 | (0.4) | 40.2 | (6.0) | 11.5 | (2.9) | — | —g | 50.5 | (16.8) | — | —g |

| Mugged/threatened with weapon | 7.6 | (0.7) | 29.7 | (2.3) | 11.5 | (2.1) | — | —g | 38.6 | (11.0) | 88.2 | (6.6) |

| Rape | 2.5 | (0.3) | 36.7 | (5.7) | 39.3 | (5.5) | 41.1 | (7.4) | 44.7 | (9.0) | 48.9 | (10.2) |

| Sexual assault | 3.8 | (0.4) | 38.8 | (4.4) | 31.3 | (4.2) | 30.8 | (7.5) | 29.2 | (7.5) | — | —g |

| Stalked | 4.4 | (0.5) | 29.1 | (4.9) | 19.7 | (4.4) | 9.2 | (3.7) | 24.0 | (7.1) | — | —g |

| Witnessed domestic violence | 7.5 | (0.5) | 42.8 | (3.0) | 15.6 | (2.3) | 7.1 | (2.5) | 40.1 | (10.3) | — | —g |

| II. Accidents | ||||||||||||

| Automobile accident | 7.8 | (0.6) | 52.8 | (2.6) | 13.0 | (2.6) | 7.1 | (2.5) | 24.0 | (9.1) | — | —g |

| Other life-threatening accident | 7.9 | (0.5) | 42.6 | (3.1) | 10.3 | (2.2) | 3.7 | (1.6) | 47.1 | (12.7) | — | —g |

| Man-made/natural disaster | 14.8 | (0.9) | 47.1 | (2.4) | 6.5 | (1.5) | — | —g | — | —g | — | —g |

| Life-threatening illness | 6.2 | (0.4) | 44.0 | (3.0) | 11.4 | (2.7) | — | —g | 29.7 | (11.9) | — | —g |

| Accidentally harmed others | 1.0 | (0.2) | 20.0 | (8.3) | — | —g | — | —g | — | —g | . | . |

| III. Network/witnessing | ||||||||||||

| Unexpected death of loved one | 28.2 | (0.8) | 63.0 | (1.8) | 10.3 | (1.2) | 8.7 | (1.4) | 34.9 | (6.3) | 36.6 | (6.5) |

| Traumatic event to loved one | 8.9 | (0.5) | 36.6 | (2.8) | 15.8 | (2.8) | — | —g | 42.3 | (8.3) | — | —g |

| Witnessed death/injury | 11.7 | (0.9) | 44.6 | (3.2) | 10.6 | (2.3) | 7.1 | (2.7) | 26.6 | (7.4) | — | —g |

| IV. Other | ||||||||||||

| Other event | 7.0 | (0.5) | 48.9 | (4.5) | 13.3 | (1.9) | 7.5 | (2.4) | 24.9 | (7.2) | 40.9 | (15.7) |

| Private event | 5.8 | (0.5) | 41.9 | (4.7) | 17.8 | (3.0) | 13.8 | (4.1) | 45.0 | (9.5) | 56.8 | (16.4) |

| χ217h = 329.8* | χ217h = 430.8* | χ210h = 64.3* | χ215h = 43.8* | χ25h = 31.5* | ||||||||

Note:

Prevalence estimates reported are the percent of the 6,483 youths in the total sample who ever experienced each of the PTEs

Respondents with a lifetime PTE were asked to select the worst PTE (i.e., the PTE associated with the worst symptoms). PTSD was queried in relation to this worst PTE. Respondents with only one PTE were asked about that PTE; respondents with multiple PTEs who were unable to identify a worst were assigned one using a random number generator.

Proportion of respondents that meet criteria for lifetime PTSD among those exposed to each PTE.

Proportion of respondents that meet criteria for lifetime PTSD among those who selected a PTE as their worst.

Proportion of respondents with 30-day PTSD among lifetime cases exposed to each PTE.

Proportion of respondents with 30-day PTSD among lifetime cases who selected a PTE as their worst.

Estimate not reported due to low precision.

χ2 tests were used to evaluate the significance of differences across PTEs in the probability that a given PTE would be chosen as worst among those exposed, in risk of lifetime PTSD among all those exposed to the PTE, and in 30-day prevalence of PTSD among lifetime cases, as information about lifetime exposure to all PTEs was used in these equations whether or not the PTE was selected as worst.

Significant at the .05 level, 2-sided test

Respondents who reported ever experiencing 1 or more PTEs were asked a screening question about whether any of these experiences was associated with symptoms such as upsetting memories or dreams, feeling emotionally distant or depressed, having trouble sleeping or concentrating, and feeling jumpy or easily startled. Respondents who answered affirmatively and had more than one lifetime PTE were asked to identify the one associated with the largest number of these symptoms. Individual PTSD symptoms were assessed for that “worst” PTE. Respondents unable to identify a worst PTE were assigned one at random from those they experienced, while respondents with only one PTE were asked about symptoms associated with that PTE. Questions assessed DSM-IV Criteria A2 (fear, helplessness, shock, horror at the time of the event), B (re-experiencing), C (avoidance-numbing), D (arousal), E (duration), and F (distress and impairment). Respondents who met DSM-IV criteria were asked about whether they still had symptoms and the number of months or years symptoms persisted. A clinical reappraisal study that blindly reinterviewed a subsample of NCS-A respondents with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children Lifetime Version (K-SADS)24 found that the 44% of respondents who endorsed the PTSD screening question accounted for 85% of clinically confirmed cases of PTSD.

Additional lifetime DSM-IV/CIDI disorders assessed in the survey included fear disorders (panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without history of panic disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, and intermittent explosive disorder), distress disorders (major depressive disorder [MDD]/dysthymia, generalized anxiety disorder, and separation anxiety disorder), behavior disorders (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], oppositional defiant disorder [ODD], and conduct disorder [CD]), substance disorders (alcohol abuse with or without dependence and drug abuse with or without dependence) and bipolar I-II and subthreshold bipolar disorder. Parents provided information about adolescent symptoms of MDD/dysthymia, ADHD, ODD, and CD. Parent and adolescent reports for these disorders showed generally good concordance and were combined at the symptom level using an “or” rule, such that a symptom was considered present if it was endorsed by either respondent.

As reported elsewhere,25 the K-SADS clinical reappraisal study mentioned above found good concordance between lifetime CIDI/SAQ and K-SADS diagnoses, with area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of .79 for PTSD, .80–.87 for other distress disorders, .81–.94 for fear disorders, .78–.98 for behavior disorders, .56–.98 for substance disorders, and .87 for any disorder.

Analysis Method

Prevalence was estimated with cross-tabulations (for number of respondents with PTE exposure and PTSD see Table S2, available online). Cumulative lifetime age-at-onset (AOO) curves for PTE exposure were calculated using the actuarial method.26 Correlates of first exposure to each lifetime PTE, PTSD among those exposed to PTEs, and PTSD recovery were examined using discrete-time survival analysis with person-year (onset) or person-month (recovery) as the unit of analysis and a logistic link function.27 Sociodemographic factors considered in the analysis included sex, person-year (<5, 5–10, 11–13, 14–15, ≥16), race-ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other), parent education (high school graduate or less vs. any postsecondary schooling), poverty (household income less than 3 times vs. more than 3 times the poverty line), number of biological parents living with the respondent, urbanicity (major metropolitan or other urban area vs. rural), and nativity (U.S. born vs. non-U.S. born). Sociodemographic factors were based on adolescent-report with the exception of poverty, which was based on parent-report. Models also included counts of the number of lifetime DSM-IV disorders the respondent had prior to age of the focal PTE. Disorders were grouped according to the results of a previous factor analysis that found NCS-A lifetime disorders to cluster into fear, distress, behavior, substance, and bipolar disorders.28

The models examining PTE exposure were initially estimated for each of the 19 PTEs, but inspection of coefficients led to collapsing the PTEs into a smaller set of 14 to combine those with similar correlates (e.g., rape and sexual assault) for purposes of the current report. (Results of models for the larger set of 19 are available on request.)

A series of progressively more complex multivariate survival models examined factors associated with PTSD onset beginning with sociodemographics (Model 1) and then adding counts of temporally prior mental disorders (Model 2) in the total sample. Subsequent models were estimated in the sub-sample of respondents with at least one lifetime PTE, including a model with only sociodemographics (Model 3), then adding type of worst event (Model 4), exposure to prior PTEs (Model 5), and DSM-IV disorders with onsets prior to PTSD (Model 6). Factors associated with PTSD recovery were examined in a similar set of progressively more complex survival models based on retrospective reports by respondents with lifetime PTSD about the duration of their episodes. Only sociodemographics were included in Model 1. Model 2 added type of worst event. Model 3 added variables for prior PTEs. Model 4 added information about PTEs that occurred in the same year or after the worst event. Model 5 added variables for number of DSM-IV disorders with onsets prior to PTSD. Information about disorders with onsets subsequent to PTSD was not examined based on concerns that these temporally secondary disorders could be PTSD severity markers. Survival coefficients and their standard errors were exponentiated and are reported as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All significance tests were evaluated using .05-level 2-sided tests. The design-based Taylor series method implemented in the SAS software system29 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina) was used to estimate standard errors.

RESULTS

Prevalence of Potentially Traumatic Experiences and PTSD

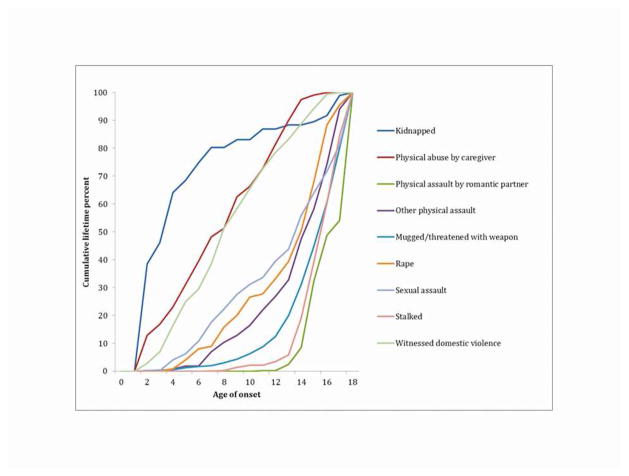

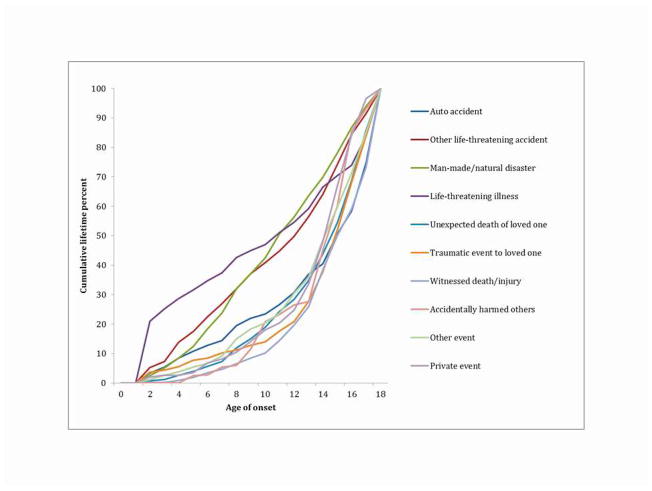

Most adolescents (61.8%) reported at least one lifetime PTE (29.1% one, 14.1% two, 18.6% three or more). The most common PTEs were unexpected death of a loved one (28.2%), man-made/natural disasters (14.8%), and witnessing death/serious injury (11.7%). (Table 1) Median age of first PTE exposure among those exposed was earliest for kidnapping, physical abuse by caregiver, and witnessing domestic violence and latest for stalked, mugged, automobile accident, and beaten up by romantic partner (Figures 1 and 2). Probability of a PTE type being selected as worst varied significantly across types (χ217=329.8, p<.001), due largely to variation in prevalence. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV PTSD was 7.6% among the 61.8% of respondents exposed to a PTE (4.7% in the total sample; 7.3% among females and 2.2% among males) and varied significantly by PTE type both when considering all lifetime PTEs (χ217=430.8, p<.001) and in considering only worst PTEs (χ210=64.3, p<.001). Rape was associated with the highest conditional probability of PTSD (39.3%) followed by kidnapping (37.0%), sexual assault (31.3%), physical assault by romantic partner (29.1%), and physical abuse by caregiver (25.2%) in the analysis of all lifetime PTEs, with similar variation in the analysis of worst PTEs. PTSD persistence also varied across PTEs (χ215=43.8, p<.001), with highest 30-day persistence for physical assault (50.5%), other life-threatening accident (47.1%), physical abuse by caregiver (45.8%), private events (45.0%), and rape (44.7%).

Figure 1.

Age of first exposure to interpersonal violence potentially traumatic experiences (PTEs) in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) among adolescents exposed to each PTE (n=6,483).

Figure 2.

Age of first exposure to other potentially traumatic experiences (PTEs) in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) among adolescents exposed to each PTE (n=6,483).

Correlates of PTE Exposure

PTE exposure varied by age, with network/witnessing events, most types of interpersonal violence, disasters, and automobile accidents most likely to occur for the first time in later adolescence than in childhood or earlier adolescence, whereas kidnapping, physical abuse by caregiver, witnessing domestic violence, and life-threatening accidents/illness all had highest odds of first occurring in childhood or early adolescence. (Figures 1 and 2) Most PTEs also varied in prevalence by gender (Tables 2 and 3). Females had higher odds than males of experiencing physical assault by romantic partner, stalking, rape/sexual assault, unexpected death of loved one, and PTE occurring to a loved one (ORs=1.4–13.6). Males had higher odds than females of experiencing accidents and physical assault and witnessing death/injury (ORs=1.4–3.3).

Table 2.

Associations (Odds Ratios) of Sociodemographics and Prior Mental Disorders With Exposure to Interpersonal Violence Potentially Traumatic Experiences (PTEs) in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A)a (n=6,483)

| Kidnapped | Physical abuse by caregiver | Physical assault by romantic partner | Other physical assault/Mugged/threatened with weaponb | Rape/Sexual assaultb | Stalked | Witnessed domestic violence | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Females | 1.1 | (0.4–2.9) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.6) | 7.0* | (2.3–21.5) | 0.3* | (0.2–0.4) | 13.6* | (8.1–22.7) | 4.5* | (2.5–8.2) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.7) |

| Males | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ21 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 11.7* | 50.1* | 97.7* | 24.3* | 1.4 | |||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.6 | (0.1–2.7) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.8) | 6.1* | (2.0–18.9) | 1.7* | (1.1–2.6) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.6) | 2.3* | (1.2–4.4) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.2* | (0.1–0.8) | 0.3* | (0.1–0.8) | 0.3 | (0.1–1.6) | 0.9 | (0.6–1.2) | 0.5* | (0.3–0.9) | 1.9* | (1.1–3.3) | 0.6* | (0.4–0.9) |

| Other | 0.7 | (0.2–2.4) | 1.0 | (0.4–2.6) | 0.8 | (0.2–3.2) | 1.8* | (1.1–3.0) | 1.4 | (0.6–3.0) | 1.5 | (0.6–3.5) | 1.8 | (0.9–3.4) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ23 | 5.6 | 5.4 | 13.5* | 21.4* | 6.0 | 7.6 | 13.3* | |||||||

| Urbanicity | ||||||||||||||

| Metro/other urban | 0.8 | (0.3–2.4) | 1.7* | (1.1–2.7) | 1.1 | (0.3–3.5) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.6) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) | 1.0 | (0.6–1.5) | 1.4 | (1.0–1.9) |

| Rural | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ21 | 0.1 | 5.3* | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 3.3 | |||||||

| Biological parents in home | ||||||||||||||

| ≤1 | 24.2* | (8.9–65.8) | 8.1* | (3.4–19.8) | 0.5 | (0.2–1.6) | 1.7* | (1.3–2.4) | 3.1* | (2.0–4.7) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.1) | 4.5* | (2.4–8.5) |

| 2 | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ21 | 39.0* | 21.5* | 1.2 | 12.4* | 26.5* | 1.9 | 22.9* | |||||||

| Prior mental disordersc | ||||||||||||||

| Fear | 0.9 | (0.4–2.2) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.8) | 1.4 | (1.0–2.1) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.7) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.4) | 1.2 | (1.0–1.5) | 1.3* | (1.0–1.6) |

| Distress | 1.5 | (0.7–3.1) | 1.1 | (0.6–1.8) | 2.1* | (1.1–3.7) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.6) | 1.5* | (1.1–1.9) | 1.4* | (1.1–1.8) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.8) |

| Behavior | 0.8 | (0.5–1.3) | 1.6* | (1.1–2.4) | 3.4* | (1.9–5.9) | 1.5* | (1.3–1.7) | 1.8* | (1.4–2.3) | 2.3* | (1.8–3.0) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.4) |

| Substance | 3.5* | (1.0–11.9) | 0.5 | (0.1–2.9) | 2.5* | (1.2–5.0) | 2.0* | (1.4–2.8) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.5) | 1.9* | (1.4–2.7) | 1.5 | (0.5–4.0) |

| Bipolar | 3.4* | (1.0–11.1) | 0.7 | (0.1–4.7) | 0.7 | (0.2–3.2) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.8) | 2.1* | (1.1–4.0) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.5) | 1.7 | (0.7–3.9) |

| χ25 | 7.3 | 13.8* | 83.4* | 145.2* | 81.3* | 102.6* | 18.3* | |||||||

Note:

Models were estimated using discrete-time survival analysis with person-years as the unit of analysis.

Based on preliminary analysis showing similar patterns of association of predictors with specific PTEs, PTEs were combined for analysis. To do so, we created a consolidated data file that stacked each of the separate PTE-specific person-year data arrays and included dummy variables to distinguish among the files, thereby forcing the estimated slopes of PTE exposure on predictors to be constant across the combined PTEs in each file. Results are based on these consolidated data arrays.

Variables represent counts of fear, distress, behavior, substance, and bipolar disorders with onsets prior to first occurrence of each PTE.

Significant at the .05 level, 2-sided test.

Table 3.

Associations (Odds Ratios) of sociodemographics and Prior Mental Disorders With Exposure to Other Potentially Traumatic Experiences (PTEs) in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A)a (n=6,483)

| Auto accident/Accidentally harmed othersb | Other life-threatening accident/Life- threatening illnessb | Man-made/natural disaster | Unexpected death of a loved one | PTE to loved one | Witnessed injury or death | Other/private event | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Females | 0.6* | (0.5–0.8) | 0.6* | (0.5–0.7) | 0.7* | (0.6–0.9) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.5) | 1.7* | (1.3–2.2) | 0.6* | (0.5–0.7) | 1.3 | (1.0–1.8) |

| Males | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ21 | 20.8* | 23.5* | 8.2* | 24.1* | 12.4* | 41.1* | 3.8 | |||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 1.4* | (1.0–1.9) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.4) | 1.1 | (0.8–1.6) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.5) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.6) | 1.6* | (1.2–2.1) | 1.1 | (0.8–1.7) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.4* | (1.0–1.8) | 0.8 | (0.6–1.1) | 1.3 | (0.9–1.8) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.7) | 1.1 | (0.8–1.5) | 2.1* | (1.6–2.8) | 1.7* | (1.2–2.3) |

| Other | 2.0 | (0.8–4.6) | 1.5 | (0.9–2.5) | 1.4 | (0.9–2.2) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.3) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.6) | 1.7* | (1.1–2.7) | 1.3 | (0.9–2.0) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ23 | 6.0 | 4.0 | 3.2 | 19.5* | 2.2 | 50.7* | 10.4* | |||||||

| Urbanicity | ||||||||||||||

| Metro/other urban | 0.7* | (0.5–0.9) | 1.2 | (1.0–1.5) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.5) | 1.0 | (0.9–1.1) | 1.4* | (1.0–1.9) | 1.4 | (1.0–2.0) | 1.5 | (1.0–2.2) |

| Rural | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ21 | 8.5* | 3.7 | 1.8 | 0.0 | 5.2* | 3.8 | 3.5 | |||||||

| Biological parents in home | ||||||||||||||

| ≤1 | 1.5 | (0.9–2.3) | 1.3 | (1.0–1.6) | 1.3 | (1.0–1.7) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.6) | 1.3* | (1.0–1.7) | 1.3 | (0.9–1.7) | 1.2* | (1.0–1.5) |

| 2 | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ21 | 2.3 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 9.4* | 4.4* | 2.4 | 4.1* | |||||||

| Prior mental disordersc | ||||||||||||||

| Fear | 1.2 | (1.0–1.6) | 1.2 | (1.0–1.4) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.6) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.5) | 1.2* | (1.0–1.4) | 1.3* | (1.1–1.6) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.4) |

| Distress | 1.2 | (0.9–1.6) | 1.6* | (1.3–2.1) | 0.8 | (0.6–1.0) | 1.0 | (0.8–1.2) | 1.4* | (1.1–1.8) | 1.4* | (1.1–1.7) | 1.3* | (1.0–1.6) |

| Behavior | 1.1 | (0.9–1.3 | 1.3* | (1.1–1.5) | 1.1 | (0.8–1.5) | 1.2* | (1.1–1.4) | 1.4* | (1.2–1.8) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.4) | 1.5* | (1.3–1.9) |

| Substance | 1.7* | (1.2–2.4) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.2) | 1.2 | (0.5–2.7) | 1.1 | (0.9–1.3) | 1.2 | (0.9–1.7) | 1.7* | (1.2–2.5) | 2.2* | (1.6–3.2) |

| Bipolar | 0.7 | (0.4–1.5) | 1.2 | (0.6–2.6) | 1.5 | (0.6–4.1) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.4) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.9) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.3) | 1.5 | (1.0–2.3) |

| χ25 | 26.3* | 61.1* | 21.8* | 33.5* | 59.9* | 35.8* | 167.1* | |||||||

Note:

Models were estimated using discrete-time survival analysis with person-years as the unit of analysis.

Based on preliminary analysis showing similar patterns of association of predictors with specific PTEs, PTEs were combined for analysis. To do so, we created a consolidated data file that stacked each of the separate PTE-specific person-year data arrays and included dummy variables to distinguish among the files, thereby forcing the estimated slopes of PTE exposure on predictors to be constant across the combined PTEs in each file. Results are based on these consolidated data arrays.

Variables represent counts of fear, distress, behavior, substance, and bipolar disorders with onsets prior to first occurrence of each PTE.

Significant at the .05 level, 2-sided test

Race/ethnicity was inconsistently associated with PTE exposure, with some PTEs more common among non-Hispanic Whites (e.g., witnessing domestic violence) and others among non-Hispanic Blacks (e.g., unexpected death of loved one), Hispanics (e.g., physical assault by romantic partner), or Others (e.g., other physical assault). Adolescents in urban areas had higher odds of physical abuse by caregiver and trauma to a loved one (ORs=1.4–1.7) and lower odds of automobile accidents (OR=0.7) than those in rural areas. Adolescents living with fewer than 2 biological parents experienced elevated odds of numerous events, including most types of interpersonal violence and network/witnessing events as well as other/private events (ORs=1.2–24.2). We also examined 3 sociodemographic factors not shown in the tables—nativity, parent education, and family income—all of which were for the most part unrelated to PTE exposure (see Table S3–S4, available online).

Pre-existing behavior disorders were associated with elevated ORs of two-thirds of PTEs including most types of interpersonal violence (ORs=1.2–3.4). Fear (ORs=1.2–1.3) and distress (ORs=1.3–2.1) disorders were associated with approximately half of PTEs each, particularly network/witnessing events. Substance disorders were associated with nearly half of PTEs (ORs=1.7–3.5). Other/private events were associated with all 4 classes of mental disorder. Bipolar disorder was associated only with rape/sexual assault and kidnapping (ORs=2.1–3.4).

PTSD Onset

Sociodemographic factors associated with PTSD in the total sample included female gender (OR=3.5), living with fewer than two biological parents (OR=2.0), and PTE exposure in early-late adolescence (ORs=1.4–1.6) compared to early childhood (Model 1; Table 4; detailed results for all correlates are in Table S5, available online). Prior mental disorders explained the association of age with PTE exposure (Model 2) due to significant associations of fear, distress, substance, and bipolar disorders with PTSD onset in the total sample (ORs=1.5–2.0).

Table 4.

Associations (Odds Ratios) of Sociodemographics, Prior Mental Disorders, and Potentially Traumatic Experience (PTE) Types With DSM-IV/CIDI PTSD Onset in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A)a (n=6,483)

| Total Sample (n=6,483)

|

Trauma-Exposed Adolescents (n=3,898)

|

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Sociodemographics | Model 2: Sociodemographics, Prior mental disorders | Model 3: Sociodemographics | Model 4: Sociodemographics, Worst event | Model 5: Sociodemographics, Worst event, Prior PTEs | Model 6: Sociodemographics, Worst event, Prior PTEs, Prior mental disorders | |||||||

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

|

|

|

|||||||||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Females | 3.5* | (2.2–5.6) | 3.6* | (2.2–5.8) | 3.6* | (2.3–5.5) | 2.8* | (1.6–4.7) | 2.8* | (1.7–4.6) | 2.5* | (1.4–4.3) |

| Males | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ21 | 27.7* | 26.5* | 34.1* | 14.3* | 16.0* | 10.7* | ||||||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||

| Hispanic | 0.6 | (0.4–1.1) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.1) | 0.5* | (0.3–0.9) | 0.6 | (0.3–1.1) | 0.6 | (0.3–1.2) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.2) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.7 | (0.3–1.5) | 0.8 | (0.4–1.6) | 0.7 | (0.4–1.4) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.5) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.6) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.4) |

| Other | 1.0 | (0.5–2.2) | 0.8 | (0.4–2.0) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.9) | 0.9 | (0.3–2.6) | 0.9 | (0.3–2.5) | 0.8 | (0.3–2.3) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ23 | 3.8 | 2.5 | 5.1 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 2.5 | ||||||

| Urbanicity | ||||||||||||

| Metro/other urban | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) | 1.3 | (0.9–1.8) | 1.1 | (0.7–1.7) | 1.2 | (0.8–1.8) | 1.4 | (0.9–2.0) |

| Rural | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ21 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 1.1 | 2.5 | ||||||

| Biological parents in home | ||||||||||||

| ≤1 | 2.0* | (1.3–3.0) | 1.8* | (1.2–2.6) | 1.8* | (1.2–2.7) | 1.8* | (1.1–2.8) | 1.5 | (1.0–2.4) | 1.5 | (0.9–2.3) |

| 2 | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ21 | 10.9* | 9.2* | 8.2* | 6.5* | 3.3 | 2.9 | ||||||

| Prior mental disordersc | ||||||||||||

| Fear | 1.5* | (1.1–1.9) | 1.7* | (1.4–2.2) | ||||||||

| Distress | 1.8* | (1.4–2.4) | 1.8* | (1.3–2.4) | ||||||||

| Behavior | 1.1 | (0.8–1.5) | 0.8 | (0.5–1.2) | ||||||||

| Substance | 1.5* | (1.0–2.2) | 1.7 | (0.9–3.2) | ||||||||

| Bipolar | 2.0* | (1.1–3.5) | 1.6 | (0.7–3.8) | ||||||||

| χ25 | 152.3* | 51.8* | ||||||||||

| Worst Evente | ||||||||||||

| χ219 | 499.0* | 557.1* | 602.1* | |||||||||

| Prior PTEsf | ||||||||||||

| χ219 | 279.7* | 93.9* | ||||||||||

Note: PTSD=posttraumatic stress disorder.

Models were estimated using discrete-time survival analysis with person-years as the unit of analysis.

Variables represent counts of fear, distress, behavior, substance, and bipolar disorders with onsets prior to occurrence of respondents’ self-reported worst PTE.

19 dummy variables included to indicate the respondents’ self-reported worst event and any other PTEs occurring in the same year as the worst.

Variables represent counts of PTEs occurring prior to respondents’ self-reported worst PTE.

Significant at the .05 level, 2-sided test

Subsequent models of PTSD onset focused on the subsample of adolescents exposed to a PTE. Sociodemographic factors associated with PTSD in that subsample (gender, living with fewer than 2 biological parents, PTE exposure in early-late adolescence) (Model 3) were compared in magnitude to those in Model 1 to determine which factors continued to be associated with PTSD onset after controlling for PTE exposure. Consistent with the unadjusted results in Table 1, PTSD risk varied significantly depending on type of worst PTE (χ219=499.0, p<.001) (Model 4). Controls for worst PTE explained the association of age with PTSD but did not explain the associations involving female gender or number of biological parents in the home. The latter demonstrates that the associations of female gender and number of biological parents with PTSD in the total sample are due to differential vulnerability to PTSD among youths exposed to PTEs rather than to differential likelihood of PTE exposure. History of prior PTE exposure was associated with PTSD onset in a subsequent model (χ219=279.7, p<.001) (Model 5), and prior PTE exposure explained the vulnerability associated with number of biological parents. A final model (Model 6) showed that prior fear (OR=1.7) and distress (OR=1.8) disorders were also significantly associated with vulnerability to PTSD but did not explain the association of female gender with PTSD.

PTSD Recovery

As shown in Table 1, 33.0% of lifetime PTSD cases met criteria for PTSD in the 30 days prior to the interview. Among those that recovered, mean time to recovery (SE) was 14.8 months (3.4). Sociodemographic factors associated with recovery (Model 1) included being born outside the U.S, which was associated with high odds of recovery (OR=11.9), and high poverty, which was associated with low odds of recovery (OR=0.3; Table 5; detailed results for all correlates are in Table S6, available online). These associations were unchanged when controls were introduced for worst PTE types, as worst PTEs were unrelated to recovery (χ23=1.0, p=.80) (Model 2). Associations of sociodemographics and worst PTEs with PTSD recovery were unchanged when prior PTEs (Model 3) and PTEs occurring after the worst event (Model 4) were included; neither prior (χ24=3.6, p=.46) nor subsequent (χ24=5.6, p=.24) PTEs predicted recovery. However, when counts of temporally prior mental disorders were added (Model 5), PTEs occurring after the worst event were significantly associated with low odds of PTSD recovery (ORs=0.2–1.1; χ24=12.6, p=.013). Bipolar disorder was also associated with low odds of recovery (OR=0.0).

Table 5.

Associations (Odds Ratios) of Sociodemographics, Potentially Traumatic Experience (PTE) types, and Prior Mental Disorders With DSM-IV/CIDI PTSD Recovery in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A)a (n=259)

| Model 1: Sociodemographics | Model 2: Sociodemographics, Worst event type | Model 3: Sociodemographics, Worst event type, Prior PTEs | Model 4: Sociodemographics, Worst event type, Prior PTEs, Subsequent PTEs | Model 5: Sociodemographics, Worst event type, Prior PTEs, Subsequent PTEs, Prior mental disorders | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |||

|

| ||||||||||

| Age of PTSD onset | ||||||||||

| Early childhood (<5) | 3.1* | (1.0–9.5) | 2.9 | (0.8–10.7) | 2.2 | (0.7–7.1) | 1.8 | (0.5–6.3) | 2.6 | (0.5–13.1) |

| Middle/late childhood (5–10) | 2.3 | (0.9–5.6) | 2.2 | (0.9–5.6) | 1.8 | (0.7–4.6) | 1.6 | (0.6–4.2) | 2.9 | (0.9–9.4) |

| Early adolescence (11–13) | 2.2 | (0.9–5.7) | 2.4 | (0.9–6.0) | 1.9 | (0.7–5.1) | 1.9 | (0.7–5.3) | 2.4 | (0.8–7.2) |

| Adolescence (14+) | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ23 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 2.5 | |||||

| Time since PTSD onset (months) | ||||||||||

| 1–3 | 2.1 | (0.7–6.4) | 2.1 | (0.7–6.1) | 2.2 | (0.7–6.5) | 1.9 | (0.6–5.6) | 2.2 | (0.8–6.1) |

| 4–6 | 0.3 | (0.1–1.3) | 0.3 | (0.1–1.2) | 0.3 | (0.1–1.3) | 0.3 | (0.1–1.2) | 0.3 | (0.1–1.2) |

| 7–12 | 1.2 | (0.3–5.0) | 1.2 | (0.3–4.9) | 1.2 | (0.3–5.1) | 1.1 | (0.3–4.2) | 1.2 | (0.3–4.6) |

| 13–24 | 4.1* | (1.4–12.1) | 4.1* | (1.4–12.0) | 4.1* | (1.4–11.6) | 3.7* | (1.4–10.1) | 4.1* | (1.7–10.1) |

| 25+ | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ24 | 18.7* | 18.7* | 18.4* | 18.2* | 18.4* | |||||

| Povertyb | ||||||||||

| High poverty | 0.3* | (0.1–0.7) | 0.3* | (0.1–0.6) | 0.3* | (0.1–0.7) | 0.3* | (0.1–0.7) | 0.3* | (0.1–0.7) |

| Low poverty | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ21 | 8.6* | 9.0* | 7.5* | 8.1* | 7.5* | |||||

| Nativity | ||||||||||

| Foreign-born | 11.9* | (2.5–56.0) | 11.1* | (2.4–51.5) | 10.5* | (2.2–50.5) | 10.9* | (1.6–74.1) | 13.0* | (2.5–69.0) |

| U.S. born | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] | 1.0 | [Reference] |

| χ21 | 9.9* | 9.4* | 8.6* | 6.0* | 8.6* | |||||

| Prior mental disordersc | ||||||||||

| Fear | 0.7 | (0.4–1.2) | ||||||||

| Distress | 1.6 | (1.0–2.7) | ||||||||

| Behavior | 1.5 | (0.9–2.5) | ||||||||

| Substance | 2.5 | (0.6–10.3) | ||||||||

| Bipolar disorder | 0.0* | (0.0–0.3) | ||||||||

| χ25 | 17.0* | |||||||||

| Worst event categoryd | ||||||||||

| χ24 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | ||||||

| Prior PTEse | ||||||||||

| χ24 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 4.7 | |||||||

| Subsequent PTEsf | ||||||||||

| χ24 | 5.6 | 12.6* | ||||||||

Note: PTSD=posttraumatic stress disorder.

Models were estimated using discrete-time survival analysis with person-years as the unit of analysis. Only respondents with lifetime PTSD were included in the analysis.

Poverty was defined using household family income for the past-year relative to the federally defined poverty line based on family size. Poverty was defined as less than three times the poverty line and low poverty (reference group) as 3 or more times the poverty level.

Variables represent counts of fear, distress, behavior, substance, and bipolar disorders with onsets prior to occurrence of respondents’ self-reported worst PTE.

Variables represent worst event type: interpersonal violence, accidents, network/witnessing, and other PTEs.

Variables represent counts of PTEs occurring prior to respondents’ self-reported worst event within each of the four PTE categories: interpersonal violence, accidents, network/witnessing, and other PTEs.

Variables represent counts of PTEs occurring after the respondents’ self-reported worst event within each of the four PTE categories: interpersonal violence, accidents, network/witnessing, and other PTEs.

Significant at the .05 level, 2-sided test

DISCUSSION

Nearly two-thirds of US adolescents report experiencing one or more PTEs by age 17, indicating substantial exposure to PTEs during childhood and adolescence, and 4.7% of U.S. adolescents meet lifetime criteria for PTSD. This prevalence estimate falls in the middle of those from previous U.S. surveys5,30 and is higher than the estimate in a recent European study.31 Our results on PTE exposure document clearly that PTEs do not occur at random, as the majority of PTEs occurred initially during adolescence and were associated with not living with both biological parents. This pattern may reflect lower parental supervision in the absence of both parents in the home, a possibility consistent with prior studies indicating that family structure is an important determinant of child-adolescent trauma exposure,32,33 or greater risk of maltreatment or exposure to other PTEs due to the presence of step-parents or other nonrelated adults in the home. The finding that females are exposed to more network/witnessing events than males is consistent with previous evidence of greater female than male emotional involvement in the stressors that occur in their social networks.34

Our finding that child-adolescent behavior disorders are associated with elevated risk of most PTEs is consistent with findings from previous studies.10,11 Behavior disorders are associated with impulsivity, risk-taking behaviors,35,36 and involvement with deviant peer groups35 that may select youths into environments where violence is common. Behavior disorders are also associated with heightened risk for exposure to maltreatment by caregivers.37,38 Fear disorders are associated primarily with network/witnessing events, whereas distress disorders are associated with violence that commonly occurs in the context of intimate relationships. One possible explanation of the former finding is that adolescents with fear disorders are more likely to attend to PTEs occurring in their social network than other adolescents39 and are therefore more likely to recall or report them. The latter finding is consistent with previous research identifying depression as a risk factor for intimate partner violence victimization.40 Substance disorders are associated with elevated risk of automobile accidents, presumably reflecting effects of intoxication on accident-proneness.

The comparatively high conditional probability of adolescent PTSD associated with PTEs involving interpersonal violence is consistent with adult studies1,18,41 and might reflect the fact that these events are associated with high perceived life threat, which has been consistently identified as one of the strongest predictors of PTSD.42,43 We find a notable gender difference in lifetime PTSD onset, with females more likely to develop the disorder than males. This elevated PTSD risk among females compared to males is also consistent with adult studies,1,18,44 although previous adolescent studies have reported mixed findings in this regard.6,8,9 Factors explaining this differential vulnerability are unknown, but may include differences in limbic and physiological stress response system reactivity to stress45,46 or fear conditioning.47

Our finding that prior PTE exposure is associated with heightened vulnerability to adolescent PTSD is also consistent with adult studies.48–50 Previous research suggests that this might be due to earlier PTEs causing heightened emotional and physiological reactivity to subsequent stressors.50,51 Although we have no way to evaluate this possibility directly, it is noteworthy that the association of prior PTEs with vulnerability to PTSD attenuated considerably when controls were introduced for prior DSM-IV disorders. This pattern is similar to recent findings suggesting that prior exposure to PTEs is associated with heightened PTSD risk only among those who developed a mental disorder following the previous PTEs.52 Finally, our finding that pre-existing fear and distress disorders were associated with elevated vulnerability to PTSD is consistent with adult studies.11,53

Some of our findings are unique to adolescents. Included here is the developmental variation in PTSD risk between childhood and adolescence, which we found to be due to age-related differences in PTE exposure, and our failure to find racial/ethnic differences in PTSD risk, which contrasts with findings of elevated PTSD risk among non-Hispanic Black adults.41 The strong association between not living with both biological parents and vulnerability to PTSD among adolescents exposed to a PTE has not to our knowledge been examined in studies of adults and might be unique to children-adolescents. This association was predominantly explained by differential exposure to prior PTEs, suggesting that not living with both biological parents increases risk of cumulative PTE exposure.

Our finding that approximately two-thirds of child/adolescent PTSD cases recovered is consistent with prior findings,1,18,19 although a number of predictors of recovery among adults, including gender, history of psychopathology, and race/ethnicity,54,55 were not significant among adolescents. Instead, low family income, nativity, exposure to temporally secondary PTEs, and bipolar disorder are significantly associated with low PTSD recovery in adolescents. Only one of these factors, exposure to secondary PTEs, has to our knowledge been examined in a previous study of adolescents, where the pattern was consistent with our findings.19 Nativity, although not examined in previous studies of youth PTSD, is known to be a significant correlate of common mental disorders due to low prevalence among first-generation U.S. immigrants compared to those born in the U.S.56 Psychopathology risk among immigrants increases with greater time in the U.S. within a single generation and across successive generations,57 potentially due to increasing exposure to acculturative stressors or to environmental factors underlying higher U.S. prevalence of mental disorders. Factors explaining high PTSD recovery among immigrant youth specifically, though, remain to be identified in future research.

A limitation of this study is that PTSD was assessed with a fully-structured lay interview with a single screening question rather than with a more sensitive semi-structured clinical interview. Our clinical reappraisal study suggests that this led to some underestimation of PTSD. As a result, the prevalence of PTSD in adolescents may in reality be more similar to adult prevalence. Another limitation is that PTSD was assessed only in relation to each respondent’s self-reported worst PTE. This is likely to have led to only a small under-estimation of lifetime PTSD prevalence, as previous research has shown that people who fail to meet criteria for PTSD for symptoms associated with a “worst” PTE only rarely meet these criteria for some other PTE.1 However, the focus on worst events could have inflated estimates of conditional probability of PTSD among people exposed to particular PTEs due to the fact that risk was estimated for a nonrepresentative sample of PTEs, although evidence suggests that bias associated with assessing PTSD in relation to worst events is minimal.58 Reporting biases are also possible with regard to worst events, particularly for situations involving multiple PTEs occurring simultaneously (e.g., a car accident involving the death of a loved one). A preferable approach in this regard would have been to assess PTSD in relation to a randomly selected PTE in order to obtain unbiased estimates of conditional risk. Such an approach was used recently in the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health Surveys59,60 before that in an epidemiological study in Detroit,49 but we are unaware of any comparable study among youths. This is an important goal for future epidemiological studies of child and adolescent PTSD.

Another limitation is that adolescents who were homeless, non-English speaking, or living in the juvenile justice system or residential treatment facilities were not included in the NCS-A. In addition to recall failure and hesitance to report PTEs, this limitation suggests that our prevalence estimates of PTE exposure and PTSD are conservative, as PTE exposure is more common in the segments of the adolescent population excluded from the sampling frame. An additional potential assessment bias is that mood-congruent recall may have led distressed respondents to report more PTEs, although prospective evidence suggests that PTE reports are largely free of over-reporting bias.61 One pattern in the NCS-A consistent with the possibility of differential recall bias is that a significantly higher proportion of females than males reported unexpected death of a loved one. As noted earlier, though, this well-known gender difference could be due to a tendency for females to have more extensive social networks than males.34 Another limitation is that a number of important factors that might predict susceptibility to PTSD were not assessed here, including temperament, parenting, and social support. In addition, because PTSD symptoms often wax and wane over time, our definition of PTSD recovery may have included adolescents still experiencing PTSD symptoms. Finally, our models examining PTSD recovery had low statistical power due to a small sample size. Cohort studies of youths with PTSD are needed to address that problem.

Despite these limitations, the results reported here document clearly that adolescence is a period of high risk of PTE exposure as well as high vulnerability to PTSD among those exposed to PTEs. We have the opportunity to reduce the population burden of PTSD both by delivering timely preventive interventions in the wake of PTEs to those most at risk of PTSD and by providing treatment to those with PTSD least likely to recover spontaneously. Effective interventions have been developed to prevent the onset of PTSD in PTE-exposed adults62 and more recently in PTE-exposed children and adolescents.63 Our findings suggest that these interventions would most usefully be targeted at youths who are victims of interpersonal violence and those with pre-existing fear and distress disorders. Effective interventions have also been developed to treat children and adolescents with PTSD.64 Our findings suggest that these interventions should specifically target adolescents living in poverty and those with comorbid bipolar disorder. Our results also suggest that these clinical interventions should be augmented with efforts to reduce onset of temporally secondary PTEs based on the fact that these later PTEs are associated with significantly reduced odds of recovery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220 and R01-MH66627) with supplemental support from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; 044780), and the John W. Alden Trust. Additional support for the preparation of this paper was provided by NIMH R01-MH093621 (K.C.K.) and K01-MH092526 (K.A.M.). The NCS-A is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. The WMH Data Coordination Centres have received support from NIMH (R01-MH070884, R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, R01-MH077883), NIDA (R01-DA016558), the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health (FIRCA R03-TW006481), the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, and the Pan American Health Organization. The WMH Data Coordination Centres have also received unrestricted educational grants from Astra Zeneca, BristolMyersSquibb, Eli Lilly and Co., GlaxoSmithKline, Ortho-McNeil, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Wyeth. We thank the staff of the World Mental Health Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis.

Mr. Hill and Drs. Petukhova, Zaslavsky, and Kessler served as the statistical experts for this research.

Footnotes

A complete list of NCS-A publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs. A public-use version of the NCS-A data set is available for secondary analysis. Instructions for accessing the data set can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/index.php. As noted above, the NCS-A is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. A complete list of World Mental Health Survey Initiative publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or US government.

Supplemental material cited in this article is available online.

Disclosure: Dr. Kessler has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca, Analysis Group, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cerner-Galt Associates, Eli Lilly and Co., GlaxoSmithKline Inc., HealthCore Inc., Health Dialog, Hoffman-LaRoche, Inc., Integrated Benefits Institute, John Snow Inc., Kaiser Permanente, Matria Inc., Mensante, Merck and Co., Inc., Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, Pfizer Inc., Primary Care Network, Research Triangle Institute, Sanofi-Aventis Groupe, Shire US Inc., SRA International, Inc., Takeda Global Research and Development, Transcept Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Wyeth-Ayerst; has served on advisory boards for Appliance Computing II, Eli Lilly and Co., Mindsite, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs, Johnson and Johnson, Plus One Health Management and Wyeth-Ayerst; has received research support for his epidemiological studies from Analysis Group Inc., Bristol- Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Co., EPI-Q, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson and Johnson Pharmaceuticals, Ortho-McNeil Janssen Scientific Affairs., Pfizer Inc., Sanofi-Aventis Groupe, Shire US, Inc., and Walgreens Co., and owns share in DataStat, Inc. Drs. McLaughlin, Koenen, Petukhova, and Zaslavsky, Mr. Hill, and Ms. Sampson report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner HA. The developmental epidemiology of childhood victimization. J Interpers Violence. 2009;24:711–731. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Census Bureau. Licensed drivers and number in accidents by age: 2009. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. The effect of lifetime victimization on the mental health of children and adolescents. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslau N, Wilcox HC, Storr CL, Lucia VC, Anthony JC. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder: a study of youths in urban America. J Urban Health: Bull N Y Acad Med. 2004;81:530–544. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ. Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:577–584. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Fairbank JA, Angold A. The prevalence of potentially traumatic events in childhood and adolescence. J Trauma Stress. 2002;15:99–112. doi: 10.1023/A:1014851823163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, Silverman AB, Pakiz B, Frost AK, Cohen E. Traumas and posttraumatic stress disorder in a community population of older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1369–1380. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199510000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuffe SP, Addy CL, Garrison CZ, et al. Prevalence of PTSD in a community sample of older adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:147–154. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199802000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koenen KC, Moffit TE, Poulin R, Martin J, Caspi A. Early childhood factors associated with the development of post-traumatic stress disorder: results from a longitudinal birth cohort. Psychol Med. 2007;37:181–192. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Storr CL, Ialongo N, Anthony JC, Breslau N. Childhod antecedents of exposure to traumatic events and posttraumatic stress disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:119–125. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler RC. Posttraumatic stress disorder: the burden to the individual and to society. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubzansky LD, Koenen KC, Spiro A, III, Vokonas PS, Sparrow D. Prospective study of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and coronary heart disease in the Normative Aging Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:109–116. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrison CZ, Bryant ES, Addy CL, Spurrier PG. Posttraumatic stress disorder in adolescents after Hurricane Andrew. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:1193–1201. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199509000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pynoos RS, Frederick C, Nader K, et al. Life threat and posttraumatic stress in school-age children. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:1057–1063. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800240031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khamis V. Post-traumatic stress disorder among school age Palestinian children. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29:81–95. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perkonigg A, Pfister H, Stein MB, et al. Longitudinal course of posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescents and young adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1320–1327. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, et al. Design and field procedures in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009;18:69–83. doi: 10.1002/mpr.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, et al. National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): II. Overview and design. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:380–385. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181999705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Üstun TB. The World Mental Health (WHM) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Green JG, et al. The National Comorbidity Survey Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A): III. Concordance of DSM-IV/CIDI diagnoses with clinical reassessments. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48:386–399. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819a1cbc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halli SS, Rao KV. Advanced Techniques of Population Analysis. New York, NY: Plenum; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willett JB, Singer JD. Investigating onset, cessation, relapse, and recovery: why you should, and how you can, use discrete-time survival analysis to examine event occurrence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:952–965. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, McLaughlin KA, et al. Lifetime co-morbidity of DSM-IV disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) Psychol Med. 2012;42:1997–2010. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® Software, Version 9.2 for Unix. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, Best CL. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:692–700. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.4.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perkonigg A, Kessler RC, Storz S, Wittchen HU. Traumatic events and post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: prevalence, risk factors and comorbidity. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101:46–59. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.101001046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. Family structure variations in patterns and predictors of child victimization. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2007;77:282–295. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lauritsen JL. How families and communities influence youth victimization. Washington, DC: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kessler RC, McLeod JD. Sex differences in vulnerability to undesirable life events. Am Sociol Rev. 1984;49:620–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burke JD, Loeber R, Birmaher B. Oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: a review of the past 10 years, part II. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:1275–1293. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200211000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schaeffer CM, Petras H, Ialongo N, Poduska J, Kellam S. Modeling growth in boys’ aggressive behavior across elementary school: links to later crime involvement, conduct disorder, and antisocial personality disorder. Dev Psychol. 2003;39:1020–1035. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.6.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ge X, Conger RD, Cadoret RJ, Neiderhiser JM, Yates W, Troughton E. The developmental interface between nature and nurture: a mutual influence model of child antisocial behavior and parent behavior. Dev Psychol. 1996;32:574–589. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moffit TE. 2005 The new look of behavioral genetics in developmental psychopathology: Gene-environment interplay in antisocial behaviors. Psychol Bull. 2005;131:533–554. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vasey MW, Daleiden EL, Williams LL, Brown LM. Biased attention in childhood anxiety disorders: a preliminary study. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1995;23:267–279. doi: 10.1007/BF01447092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smith SM, Smith DB, Penn CE, Ward DB, Tritt D. Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: a meta-analytic review. Aggress Violent Behav. 2004;10:65–98. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, Koenen KC. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychol Med. 2011;41:71–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:748–766. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ozer EJ, Best SR, Lipsey TL, Weiss DS. Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:52–73. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Breslau N, Davis GC, Andreski P, Peterson EL. Sex differences in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:1044–1048. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830230082012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stroud LR, Papandonatos GD, Williamson D, Dahl R. Sex differences in the effects of pubertal development on responses to corticotropinreleasing hormone challenge. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1021:348–351. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang J, Korczykowski M, Rao H, et al. Gender differences in neural response to psychological stress. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2007;2:227–239. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inslicht SS, Metzler TJ, Garcia NM, et al. Sex differences in fear conditioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Kessler RC, Davis GC. Previous exposure to trauma and PTSD effects of subsequent trauma: results from the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:902–907. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bromet E, Sonnega A, Kessler RC. Risk factors for DSM-III-R posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:353–361. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLaughlin KA, Conron KJ, Koenen KC, Gilman SE. Childhood adversity, adult stressful life events, and risk of past-year psychiatric disorder: a test of the stress sensitization hypothesis in a population-based sample of adults. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1647–1658. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709992121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McLaughlin KA, Kubzansky LD, Dunn EC, Waldinger R, Vaillant G, Koenen KC. Childhood social environment, emotional reactivity to stress, and mood and anxiety disorders across the life course. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:1087–1094. doi: 10.1002/da.20762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Breslau N, Peterson EL, Schultz LR. A second look at prior trauma and the posttraumatic stress disorder effects of subsequent trauma: a prospective epidemiological study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:431–437. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.4.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Koenen KC, Moffit TE, Caspi A, Gregory A, Harrington H, Poulton R. The developmental mental-disorder histories of adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a prospective longitudinal birth cohort study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117:460–466. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.2.460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Breslau N, Davis CG. Posttraumtic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults: risk factors for chronicity. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:671–675. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.5.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koenen KC, Stellman JM, Stellman SD, Sommer JF., Jr Risk factors for course of posttraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans: a 14-year follow-up of American Legionnaires. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:980–986. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Borges G, Kendler KS, Su M, Kessler RC. Risk for psychiatric disorder among immigrants and their US-born descendants: evidence from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2007;195:189–195. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243779.35541.c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vega WA, Kolody B, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alderete E, Catalano R, Caraveo-Anduaga J. Lifetime prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders among urban and rural Mexican Americans in California. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:771–778. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Breslau N, Peterson EL, Poisson LM, Schultz LR, Lucia VC. Estimating post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: lifetime perspective and the impact of typical traumatic events. Psychol Med. 2004;34:889–898. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Karam EG, Andrews G, Bromet E, et al. The role of criterion A2 in the DSM-IV diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stein DJ, Koenen KC, Friedman MJ, et al. Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence from the World Mental Health Surveys. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;73:302–312. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dohrenwend BP, Turner JB, Turse NA, et al. The psychological risks of Vietnam for U.S. veterans: a revisit with new data and methods. Science. 2006;313:979–982. doi: 10.1126/science.1128944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Foa EB, Hearst-Ikeda D, Perry KJ. Evaluation of a brief cognitive-behavioral program for the prevention of chronic PTSD in recent assault victims. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:948–955. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.6.948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berkowitz SJ, Stover CS, Marans SR. The Child and Family Traumatic Stress Intervention: secondary prevention for youth at risk of developing PTSD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:676–685. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cohen JA, Deblinger E, Mannarino AP, Steer RA. A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:393–402. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200404000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.