Abstract

Recent studies have suggested a possible involvement of abnormal tau in some retinal degenerative diseases. The common view in these studies is that these retinal diseases share the mechanism of tau-mediated degenerative diseases in brain and that information about these brain diseases may be directly applied to explain these retinal diseases. Here we collectively examine this view by revealing three basic characteristics of tau in the rod outer segment (ROS) of bovine retinal photoreceptors, i.e., its isoforms, its phosphorylation mode and its interaction with microtubules, and by comparing them with those of brain tau. We find that ROS contains at least four isoforms: three are identical to those in brain and one is unique in ROS. All ROS isoforms, like brain isoforms, are modified with multiple phosphate molecules; however, ROS isoforms show their own specific phosphorylation pattern, and these phosphorylation patterns appear not to be identical to those of brain tau. Interestingly, some ROS isoforms, under the normal conditions, are phosphorylated at the sites identical to those in Alzheimer’s patient isoforms. Surprisingly, a large portion of ROS isoforms tightly associates with a membranous component(s) other than microtubules, and this association is independent of their phosphorylation states. These observations strongly suggest that tau plays various roles in ROS and that some of these functions may not be comparable to those of brain tau. We believe that knowledge about tau in the entire retinal network and/or its individual cells are also essential for elucidation of tau-mediated retinal diseases, if any.

Keywords: tau, neurodegenerative diseases, microtubule-associated proteins, retinal degenerative diseases

1. Introduction

Microtubules (MTs), a major component of the cytoskeleton, participate in numerous cellular processes ranging from cell division, organelle positioning, intracellular transport, to neuronal differentiation. The MT-associated protein tau is the best known for its being essential for the assembly and stabilization of MTs in the neuronal system [1–3]. Thus, it is understandable that tau dysfunction is correlated with a variety of neurodegenerative diseases including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), front-temporal dementia with parkinsonism linked to chromosome (FTDP-17) and Pick’s disease and that these diseases are referred to as ‘tauopathies’ [4–6].

Expression of tau in the neuronal system is extraordinary complicated: Multiple tau isoforms are generated from a single gene through alternative mRNA splicing in a developmental stage-and cell type-specific manner [7]. In human adult brain tau, exons 1, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12 and 13 are constitutive and exons 2, 3, and 10 are alternatively spliced [7, 8]. Exons 4A, 6, and 8 appear not to be transcribed. Exon 14 is transcribed, but not translated. In turn, matured human brain tau primary transcript gives rise to six mRNA: (Δ6,8), (Δ6,8,10), (Δ3,6,8), (Δ3,6,8,10), (Δ2,3,6,8), and (Δ2,3,6,8,10). These tau isoforms contain repetitive regions serving as MT-binding sites in a domain encoded by exons 9–12. Tau isoforms resulting from encoding exon 10 have four repeat regions, whereas those lacking encoding exon 10 have three repeat regions [5–10]. Various factors such as localization of abnormal tau affect the development of neurodegenerative diseases. Here we emphasize that the splicing also appears to play a role(s) in the pathogenesis of these diseases. In AD, all six isoforms of brain tau have been found in the neurofibrillary tangle of paired helical filaments (PHFs), a hallmark of AD [11, 12]. Inclusion bodies in FTDP-17 contain only tau isoforms with four MT-binding regions [13], whereas inclusion bodies in Pick’s disease are entirely made from tau isoforms with three MT-binding regions [14, 15].

Regulation of tau is also highly complicated: Tau is tightly regulated by phosphorylation [2, 10, 16]. Remarkably, phosphorylation can occur at 30–40 different sites in tau [17–20]. Normal human brain tau contains 2–3 moles of phosphate per mole of protein, which appears to be optimal for its interaction with tubulin and promotion of MT assembly [21]. However, the level of tau phosphorylation in AD brain is 3- to 4 times higher than that in normal brain [22, 23], and, to date, ~20 phosphorylation sites have been identified in tau associated with PHFs [17, 24]. Two models have been proposed for the mechanism leading to neurodegenerative diseases by hyperphosphorylation: “toxicity” and “erroneous regulation” [25]. In the former model, hyperphosphorylation leads to formation and accumulation of toxic tau fibers and these fibers cause cell death by virtue of their cytotoxicity [26, 27]. In the latter model, hyperphosphorylation converts normal tau to an inhibitory molecule that sequesters normal MT-associated proteins from MTs and, in turn, leads to cell death [25, 28]. The following enzymes have been identified as major tau protein kinases: cAMP-dependent protein kinase (EC 2.7.11.11), Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (EC 2.7.11.17), cyclin-dependent protein kinase 5 (Cdk5) (EC 2.7.11.22), stress-activated protein kinases (EC 2.7.11.24) and glycogen-synthase kinase-3β (EC 2.7.11.26).

The retina, a part of the visual system, contains both tau [29, 30] and protein kinases responsible for brain tau hyperphosphorylation [31, 32]. Recent studies suggest that abnormal tau may play a role in some retinal degenerative diseases [33–41]. A common viewpoint in these studies is that these retinal diseases may share, at least in part, the mechanism of tau-related brain diseases and that information about these brain diseases may be applied to explain these retinal diseases. This view may use to collectively analyze these retinal diseases. However, the basis of this view may not be strong, i.e., to our understanding, tau in retina (or in individual retinal cells) has not been thoroughly characterized, and the characteristic of retinal tau has not been fully compared with that of brain tau. In addition, the information about retinal tau is based on the tau derived from the whole retina that is composed of various cells, and thus some characteristics may be blurred.

This study collectively examines the common view of these previous studies by characterizing tau in bovine retinal photoreceptor rod outer segments (ROS), i.e., in a single type of retinal cells, and by comparing its characteristics with that of bovine brain tau. We ask three basic questions in the characterization: (1) whether ROS contains tau isoforms identical to those in brain, (2) whether ROS tau shows the phosphorylation pattern similar to that of brain tau, and (3) whether ROS tau interacts with MTs in a manner similar to that of the association of brain tau with MTs. We show that ROS tau is not necessarily similar to brain tau and that the difference from brain tau as well as the similarity with brain tau should be considered in the investigation of tau-related degenerative diseases, if any, in retina.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Dark-adapted frozen bovine retinas were obtained from J. A. Lawson Co. (Lincoln NE). Fresh retinas were isolated from dark-adapted calf eyes obtained from a local slaughterhouse. Bovine brain was obtained from a local slaughterhouse. Alkaline phosphatase (AP) (EC 3.1.3.1) from E. coli was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Immobilon-PSQ transfer membrane was from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Ultra Super Signal chemiluminescent substrate and peroxidase-labeled anti-rabbit IgG and anti-mouse IgG were from Pierce (Rockford, IL). Ampholyte (3–10, 40%), Ampholyte (4–6, 40%), Ampholyte (5–8, 40%), Ampholyte (8–10, 20%) and IPG-strips were obtained from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). All other chemicals were purchased from Sigma unless otherwise indicated.

2.2. Antibodies

Rabbit anti-human tau antibody (A0024, 1:5,000), obtained from Dako (Carpinteria, CA), was regularly used. Phosphorylation site-specific antibodies, PS262 (44750G), PS396 (44752G) and PS404 (44758G), and their blocking peptides were from Biosource (Camarillo, CA). Anti-α-tubulin monoclonal antibody (T5168, 1:5,000) and anti-β-tubulin monoclonal antibody (T5293, 1:200) were from Sigma.

2.3. Preparation of bovine brain and ROS samples

This study used bovine preparations unless otherwise indicated. The reasons for the use of bovine preparations are described in the Discussion. Protein concentration was assayed with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard [42]. Bovine brain (5 g protein) was suspended in 5 volumes of a 1.5 times-concentrated Buffer A (10 mM HEPES, pH 8.2, 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 5 mM MgCl2, 5 μM leupeptin, 5 μM pepstatin A, 0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 9.5 TIU/l aprotinin and 1 μM E-64) and homogenized by using a 18 G needle (x7) and then a 23 G needle (x7). The mixture was divided into 200 μl aliquots per tube and kept at −80 °C. Bovine ROS was obtained from dark-adapted frozen retinas [43] or fresh retinas from dark-adapted calf eyes [44]. After homogenizing in 400 μl of Buffer A, ROS (1.0 mg protein) was centrifuged (350,000 × g, 20 min, 4 °C) to obtain membrane and soluble fractions. The soluble fraction was again centrifuged to remove contamination by membranes. The precipitation was suspended in 400 μl of Buffer A and used as the membrane fraction.

2.4. Identification of tau isoforms

Bovine tau isoforms are generated from a single gene, and their molecular weights (MWs) are distinctive. Therefore, ROS tau proteins having identical MWs to those of brain tau isoforms are regarded as ROS tau isoforms containing the same exon combination as those in brain tau. Here SDS-PAGE was used to obtain these MWs, i.e., their apparent MWs were compared. The SDSPAGE system we used has been proven to be excellent for protein isolation [45].

Brain (1.0 mg protein) and ROS (1.0 mg protein) were separately suspended in 400 μl of Buffer A. Each preparation was divided into two tubes (150 μl), and to each tube, 10 μl of an AP solution (32 unit/ml AP, 0.32 % NaN3 and 1.6 mM ZnCl2) or 10 μl of a phosphatase-inhibitor solution (160 mM NaF, 1.6 μM okadaic acid, 0.32 % NaN3 and 1.6 mM ZnCl2) was added, and these mixtures were incubated for 18 h at 33 °C. After adjusting the volume of ROS and brain mixtures by adding Buffer A to 300 μl and 1200 μl, respectively, 10, 20, 30 and 40 μl of these samples were applied to a 8–16% acrylamide-gradient gel (12 × 17 cm). Proteins were then blotted to a nylon membrane and tau was detected with a rabbit anti-human tau antibody. These proteins are named tau-antibody-sensitive proteins hereafter.

Antibody signal intensities were used for the estimation of tau concentration in ROS, because this allows the concentration to be measured rapidly and simultaneously when multiple tau isoforms are present. However, a linear relationship between the signal intensity and the protein level is difficult to establish. To reduce this ambiguity, four samples containing different protein amounts were applied to a gel and their signal intensities were compared. All experiments were carried out three times and the results were similar. The data shown are representative of these experiments.

2.5. Determination of the phosphorylation status of tau isoforms in ROS

After treatment with or without AP, proteins were separated by regular SDS-PAGE or two-dimensional electrophoresis. The phosphorylation status was then estimated based on the changes in their migration profiles caused by the AP treatment. (1) Regular SDS-PAGE. After isolation, tau proteins were detected with an anti-human tau antibody, as described above. (2) Two-dimensional electrophoresis. ROS (1–5 mg protein) was homogenized in 200 μl of Buffer A and centrifuged (350,000 × g, 20 min, 4 °C). The soluble fraction was again centrifuged to remove contamination by membranes. The membrane fraction was washed with 200 μl of Buffer B (10 mM MOPS, pH 7.5, 1 mM DTT, 5 mM MgCl2, 5 μM leupeptin, 5 μM pepstatin A, 0.1 mM PMSF and 200 mM NaCl) (x2). Then its volume was adjusted to 200 μl by adding Buffer A. These preparations were divided into two tubes (70 μl), and 5 μl of the AP solution or 5 μl of the phosphatase-inhibitor solution was added to each tube. These mixtures were incubated for 18 h at 33 °C. These samples were then subjected to non-equilibrium pH-gradient electrophoresis. In brief, these samples were mixed with 305 μl of 1.26 time-concentrated rehydration buffer {7M urea, 2M Thio-urea, 4% CAHPS, 50 mM DTT, 0.1% Ampholyte (3–10, 40%), 0.1% Ampholyte (4–6, 40%), 0.1% Ampholyte (5–8, 40%), 0.1% Ampholyte (8–10, 20%), and 0.001% bromophenol blue) and applied to IPG-strip (11 cm, pH 3–10), and active rehydration was performed in an IEF Cell (Bio-Rad) as recommended by the manufacture. The proteins were focused at 3400V for 36,000Vh. The strips were equilibrated under reducing conditions (6M urea, 20% glycerol, 2% SDS, 2% DTT, and 0.375M Tris, pH 8.8) for 15 min and then alkylated for 15 min (6M urea, 20% glycerol, 2% SDS, 2.5% iodoacetamide, and 0.375M Tris, pH 8.8). Each strip was then transferred to a vertical SDS-PAGE with an 8–16% acrylamide-gradient gel (12 × 17 cm).

2.6. Detection of tau and tubulins by immunogold electron microscopy

Rat (Wister rat) and frog (Rana catesbiana) retinas isolated freshly were used to avoid possible postmortem changes in bovine retina. Western blotting using the tau antibody sensitive to bovine tau showed that tau-antibody-sensitive proteins in rat and frog retinas were similar, if not identical, to those in bovine retinas although the level of frog proteins appeared to be slightly less. These animal experiments were approved by the Regulatory Committee of Animal Experiments in Nagoya University and conformed to the guidelines outlined in the National Instituted of Health Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Rat retinas were fixed with 1% glutaraldehyde and 4% paraformaldehyde in 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). Frog retinas were also treated in the same way. These retinas were dehydrated through an ascending series of ethanol up to 95 %, and then soaked in a mixture of Lowicryl K4M resin (Polysciences Inc. Warrington, PA) and 95% ethanol for 1hour. Specimens were transferred into fresh Lowicryl K4M resin and keep in refrigerator over night. Retinas were again transferred into gelatin capsules filled with fresh Lowicryl K4M resin and polymerized under UV light for 3 days. Thin sections were obtained in a conventional way and mounted on 200-nickel-grid coated with formval. Protein labeling was then carried out as previously described [46]. In brief, the sections blocked with 4% BSA for 10 min were incubated with anti-tubulin α or β antibodies or anti-tau antibody (final concentration 0.2 mg/ml) in PBS containing 1% BSA for 2 h, rinsed 7 times with PBS, and then incubated on 10 or 15 nm gold-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or -mouse IgG (Amersham, Uppsala, Sweden) at a dilution of 1:30 in 1% BSA/TBS for 1 h. After being washed 8 times with PBS (1 min each), grids were post-fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde for 20 min and washed well with distilled water. Control sections were processed in the same way, except that preimmune serum was substituted for the anti-tubulin and anti-tau protein antibodies. As another control, an excess amount of peptide antigen (2mg/ml: 10 times higher than the antibody concentration) was added during primary antibody incubation. Two controls showed the same images without specific labeling. All sections were stained with 5 % uranyl acetate in distilled water prior to observation.

3. Results

3.1. Bovine brain tau

This study characterizes bovine ROS tau based on information about bovine brain tau. Bovine brain tau isoforms, like human brain tau isoforms, are generated from a single gene through alternative mRNA splicing [7, 47]: Exons 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12 and 13 are found in all tau isoforms, while exons 3, 8 and 10 are alternatively spliced. Isoforms having domains encoded by exons 6 and 14 were reported; however, levels of these isoforms were negligible [47]. Isoforms containing the domain encoded by exon 8 were also present; but their total level was less than 2% of the total tau [48]. Therefore, it has been concluded that bovine brain tau has four major isoforms (Δ6,8), (Δ6,8,10), (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10) (Fig. 1). These four isoforms were actually obtained from bovine brain [8, 49]. Importantly, these isoforms are also present in human brain [4, 10]. In addition, all tau domains, especially domains encoded by exons 9–13, are homologous in these two species (Fig. 1). It is thus expected that the primary property of bovine brain tau is quite similar to that of human brain tau. As an example for the structure similarity, anti-human tau antibodies recognize bovine brain tau isoforms, as shown previously [7, 8] and below.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of bovine tau exons and major tau isoforms exited in bovine brain. (A) Exons. Numbers below each exon indicate the MW of the domain encoded by the exon and the level of its homology with that of human brain tau. These MWs were calculated based on their amino acid sequences. Neither the MW nor the level of homology of polypeptides encoded by exons 6 and 8 is shown because these exons are not transcribed in human brain. Ser269, Ser403 and Ser411 are the phosphorylation sites we focus on in this study. The relative size of these exons is not drawn to scale. (B) Four major tau isoforms in brain. Their calculated MWs were obtained based on their amino acid sequences.

Based on their migration profiles published previously [8], we estimated the apparent MWs of major bovine brain tau isoforms (Fig. 1). Three points should be noted. First, these apparent MWs are much larger than their calculated MWs, i.e., the MWs predicted from their cDNA sequences. This characteristic is also observed in human brain tau and is believed to be due to its hydrophilicity [10, 50]. Second, the apparent MW of isoform (Δ6,8,10) is lager than that of isoform (Δ3,6,8) although the calculated MW of the former isoform is smaller than that of the latter isoform (Fig. 1). This inconsistency is also observed in human brain tau isoforms [8, 51]. These observations imply that the domain encoded by exon 3 and/or 10 is crucial for the structure of tau protein. Third, these apparent MWs were obtained by SDS-PAGE. The SDS-PAGE conditions may not be identical in all experiments, and thus the apparent MW obtained may vary. This study compared apparent MWs of ROS tau isoforms with those of brain isoforms for identification of ROS isoforms. We compare these MWs only when these MWs are obtained under exactly the same conditions for SDS-PAGE.

3.2. Identification of tau isoforms present in bovine ROS

After separation by SDS-PAGE, the migration profile of ROS tau was compared with that of bovine brain tau (Fig. 2). We found that ROS contained tau-antibody-sensitive proteins of which apparent MWs were identical to those of brain major tau isoforms, i.e., ROS contained isoforms (Δ6,8), (Δ6,8,10), (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10). We also found that ROS had seven additional tau-antibody-sensitive proteins (★1–★7). Proteins (★1), (★2), (★6) and (★7) do not have apparent MWs identical to any of brain proteins; but proteins (★3–★5) appear to have apparent MWs identical to those of brain proteins (★b–★d), respectively (Fig. 2B). Among them, levels of isoforms (Δ6,8,10), (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10) and tau-antibody-sensitive protein (★5) and (★7) were evidently large in ROS. Their antibody signal intensities indicates that the order of these levels was: isoform (Δ3,6,8,10) ≥ isoform (Δ3,6,8) > protein (★7) > isoform (Δ6,8,10) > protein (★5). Interestingly, the level of isoform (Δ6,8), one of major isoforms in brain, appears to be negligible in ROS, and protein (★5), one of major isoforms in ROS, seems to be negligible in brain. The result also indicates that apparent MWs of ROS tau isoforms, similarly to brain tau isoforms, were much higher than their calculated MWs.

Figure 2.

Detection of tau isoforms existed in bovine ROS. (A) Comparison of running profiles of bovine ROS tau isoforms with those of bovine brain isoforms. Preparations of ROS and brain (1mg) were suspended in 400 μl of Buffer A. After divided into two tubes (150 μl), each preparation was treated with or without AP. After diluting with the same buffer to 300 and 1200 μl, respectively, these preparations (10, 20, 30 and 40 μl) were applied to a SDS-gel and tau-antibody-sensitive proteins were detected. (B) In-depth comparison of the running profile of ROS tau-antibody-sensitive proteins with that of brain isoforms. A running profile of ROS proteins (lane a in A) is compared with that of brain proteins (lane b in A). Four tau isoforms were identified to be identical to bovine brain isoforms. Unknown are exons encoded following isoforms (*1, – *7 in ROS, and *a – *g in brain).

Treatment with AP entirely dephosphorylates ROS tau isoforms, as shown later (Fig. 3). This AP treatment categorizes these ROS tau-antibody-sensitive proteins into four groups: (1) Proteins detected clearly after the AP-treatment. Proteins (★1), (Δ6,8) and (★2) belong to this group (Fig. 2A). This phenomenon was also seen in membranous tau-antibody-sensitive proteins (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, this phenomenon was observed only with proteins having relatively higher apparent MWs (Figs. 2A and 5A), and clear detection often accompanied an increase in the amount of these proteins (Fig. 5A). The simplest explanation of these observations is that only these proteins had been phosphorylated and thus would diffuse on the SDS-gel and that these proteins, when dephosphorylated, would be concentrated into their own protein-bands and thus appeared to increase their amounts. Alternatively, if all or most of tau-antibody-sensitive proteins had been phosphorylated, the phosphorylation level of these proteins would be much higher than that of other proteins. Importantly, bovine brain proteins did not show the same phenomenon (Fig. 1A). (2) Proteins reducing their quantities with the AP treatment. Isoform (Δ6,8,10) belongs to this group (Fig. 2A). This phenomenon was also observed in membranes (Fig. 5A). The simplest explanation of the observation is that isoform (Δ6,8,10) had been phosphorylated and that dephosphorylation would change its conformation followed by increase in its sensitivity to proteolytic digestion. The proteolytic enzyme should be specific to the isoform because isoforms (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10) did not reduce their quantities under the same conditions. In brain, tau-antibody-sensitive protein (★a) and isoform (Δ6,8) appeared to show this phenomenon (Fig. 2A). (3) Proteins unaffected by the AP treatment. Isoforms (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10) and tau-antibody-sensitive protein (★5) belong to this group. These proteins may not be phosphorylated or if phosphorylated, their conformations may not be affected by dephosphorylation. In brain, isoforms (Δ6,8,10), (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10) belong to this group. (4) Proteins increasing their quantities with the AP-treatment. Tau-antibody-sensitive protein (★7) may belong to this group (Figs. 2A and 5A). Whenever protein (★7) was clearly detected, the level of isoform (Δ6,8,10) was always reduced (Figs. 2A and 5A), suggesting that protein (★7) may be a digested product of isoform (Δ6,8,10). We also note that protein (★7) was sometimes vaguely detected, as shown later (Fig. 4). The simplest explanation of this observation is that the proteolytic digestion of isoform (Δ6,8,10) might be somehow suppressed, and thus protein (★7) might not be produced. All together, we speculate that protein (★7) may be an artifact and not be a tau-antibody-sensitive protein present originally in ROS. In brain, tau-antibody-sensitive protein (★a) and isoform (Δ6,8) appeared to reduce their quantities with AP treatment. However, the protein corresponding to protein (★7) was not detected. These brain proteins might have been further digested and then diffused.

Figure 3.

Running profile of tau-antibody-sensitive proteins present in ROS membranes in the two-dimensional electrophoresis. (A) Use of a relatively large amount of membranes. After homogenization of a ROS preparation (1 mg) in 400 μl of Buffer A, membranous fractions were obtained. The membrane fraction was treated with or without AP, and proteins were separated by a pH gradient and then by their MWs. (B) Use of a relatively small amount of membranes. ROS membranes (100 μg) were subjected to the two-dimensional electrophoresis. Exposure time of the tau/antibody-attached nylon membrane to films was two times longer than that in (A). A part containing the tau-antibody-sensitive proteins belonged to group a is enlarged. Two isoforms (★1) and (★2) are identified as isoforms (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10), respectively.

Figure 5.

Solubility of ROS tau-antibody-sensitive proteins. (A) Tau-antibody-sensitive proteins in membrane and soluble fractions. Soluble and membranous fractions were obtained from ROS (1.0 mg). After adjusting volumes of these fractions to 400 μl by adding Buffer A, each fraction was divided into two portions (150 μl) and treated with or without AP. After diluting with the same buffer to 300 μl, these preparations (10, 20, 30 and 40 μl) were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and then proteins were detected using a tau-specific antibody. (B) Tau-antibody-sensitive proteins in Buffer A containing n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside. ROS membranes (500 μg) were suspended in Buffer A (200 μl) containing 1% n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside and incubated for 1 hour on ice. The mixture was centrifuged, and the precipitate and supernatant were obtained. After adjusting the volume to 150 μl by adding the same buffer, these samples (10, 20, 30 and 40 μl) were applied to a SDS-gel, and proteins were tau detected. (C) Tau-antibody-sensitive proteins in Buffer A containing Triton X-100. ROS membranes (500 μg) were suspended in Buffer A (200 μl) containing 1% of Triton X-100, incubated and centrifuged, as described in (B). After adjusting the volume to 150 μl by adding the same buffer, these samples (50 μl) were applied to a SDS-gel and tau isoforms were detected as described in (B). The tau-antibody-sensitive protein (✶) was identified as protein (★7).

Figure 4.

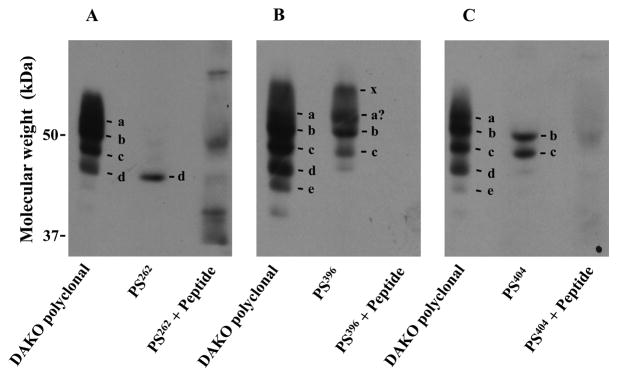

Some of ROS tau isoforms contain phosphorylated sites identical to those in tau isoforms associated with PHFs. Phosphorylation-site-specific antibodies against human tau, PS262 (A), PS396 (B) and PS404 (C), were used to identify bovine isoforms having these phosphorylated sites, Ser269, Ser403 and Ser411, respectively. Membranes were obtained from a ROS preparation (850 μg) and suspended in 640 μl of Buffer A. The suspension, 10 and 50μg protein, were subjected to SDS-PAGE. Then proteins were blotted to an Immobilon-P nylon. ROS tau isoforms in each lane were then detected: lane 1, 10 μg protein and DAKO polyclonal anti-human tau antibody; lane 2, 50 μg protein and a phosphorylation-site-specific antibody; and lane 3, 50 μg protein and a phosphorylation-site-specific antibody pretreated with an antigen-peptide. Pretreatment with antigen-peptides was carried out as recommended by the manufacture. The following tau antibody-sensitive proteins were identified in lane 1: a, isoform (Δ6,8,10); b, isoform (Δ3,6,8); c, isoform (Δ3,6,8,10); d, isoform (★5) and e, tau-antibody-sensitive protein (★7). x is an unidentified protein.

Based on observations described above, we conclude as follows: (1) Bovine ROS contains at least four tau isoforms (Δ6,8,10), (Δ3,6,8), (Δ3,6,8,10) and (★5). This implies that tau isoforms may play a variety of roles in ROS. (2) Isoform (★5) is present in ROS but may not be present or be negligible in brain. The protein may be a ROS-specific (or retina-specific). In addition, the level of isoform (Δ6,8), one of major isoforms in brain, appears to be negligible in ROS. These observations strongly suggest that combination of ROS isoforms is different from that of brain isoforms, i.e., functions of ROS tau may not be comparable to those of brain tau. (3) ROS tau isoforms, at least some, are phosphorylated.

Apparent MWs of bovine brain tau isoforms we obtained (Fig. 2B) were different from those previously reported (Fig. 1). This difference may be due to the different conditions for SDS-PAGE as described above. We also note that the migration profile of ROS tau-antibody-sensitive proteins was not changed even after long incubation (for 18 h at 33 °C), suggesting that these proteins might not be spontaneously dephosphorylated under our conditions. Various phosphatase inhibitors added to the incubation mixture might be functional. Alternatively, their migration profiles would be unchanged even if some of them were spontaneously dephosphorylated. We further note that migration profiles of these ROS proteins obtained freshly from calf eyes were similar, if not identical, to those from frozen retina, implying that biochemical characteristics of these proteins such as their phosphorylation status may be unchanged or their changes may be negligible during storage of these retinas. Similarly, biochemical characteristics of brain tau might not be affected by postmortem changes although we cannot deny the possibility.

3.3. Analysis of ROS tau isoforms with two-dimensional electrophoresis

After treating with or without AP, tau isoforms in ROS membranes were separated first by isoelectric focusing and then by vertical SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A). We found that tau-antibody-sensitive proteins present in ROS membranes were separated into two groups; group a: proteins scattered in a pH range ~6.7–8.3, and group b: proteins concentrated in a narrow range above pH 8.3. We also found that proteins in group a were dominant before the AP treatment, whereas only proteins belonged to group b were present after the AP treatment. These observations strongly suggest that proteins in group a were phosphorylated, while proteins in group b were completely dephosphorylated. We note that spontaneous dephosphorylation on proteins in group a cannot be denied during the long incubation, as discussed above. However, the result (Fig. 3A) clearly indicates that tau-antibody-sensitive proteins are still phosphorylated even after the possible spontaneous dephosphorylation. The soluble fraction was also examined; however, the result was not clear due to a very low content of tau proteins. This low content is due to their tight binding to membranes. This characteristic will be described later (Figs. 5 and Supplementary data).

Proteins in group a were clearly separated from proteins in group b (Fig. 3A). This observation, together with the observation that almost all proteins belonged to group a before the AP treatment (Fig. 3A, -AP), strongly suggests that all tau-antibody-sensitive proteins present in membranes were phosphorylated. Almost all these proteins are membrane-bound, as described above. We therefore conclude that all ROS tau isoforms are phosphorylated. The phosphorylation status of isoforms (Δ3,6,8), (Δ3,6,8,10) and (★5) was not clear in the result depicted in Figure 2. However, this study clearly indicates that these isoforms are also phosphorylated. Phosphatase 2A (EC 3.1.3.16), a major protein phosphatase for dephosphorylation of hyperphosphorylated tau isoforms in human brain [4, 10, 52], is present in ROS [53, 54]. However, the observation (Fig. 3A) suggests that the enzyme activity had been suppressed. Inhibitors we added might deactivate the enzyme. ROS used in this study was obtained from fresh retina of ordinary calf eyes or frozen bovine retina, i.e., the great majority of ROS was obtained from normal retinas. Thus, it is concluded that all tau isoforms present in ROS are phosphorylated under the normal conditions.

The precise migration profile of tau-antibody-sensitive proteins in group a was obtained by using a small amount of ROS membranes (Fig. 3B). In this case, two tau isoforms (★1) and (★2), based on their apparent MWs and quantities, were identified as isoforms (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10), respectively. The migration profile showed that these isoforms lined up as if they were scattered on two parallel curves extended to points with a lower apparent MW and with a higher apparent isoelectric point (pI). A similar profile was also obtained when a large amount of ROS membranes was used, although isoforms were not clearly separated due to the overload of proteins (Fig. 3A, -AP). The simplest explanation of the profile is that each isoform chain consists of the same isoform, that the isoform with the lowest apparent pI is modified with the highest numbers of phosphate and that the phosphate number is reduced stepwise as shifting to the next spot with a higher apparent pI (and a lower apparent MW), but the isoform having the highest apparent pI still contains a phosphate molecule(s). Thus, it is likely that tau isoform, even the isoform having the same structure, is modified with a variable number of phosphate molecules in ROS. In addition, the tau antibody-signal intensities of these spots were not even (Fig. 3B), suggesting that amounts of tau isoforms phosphorylated differently also varied. How complicatedly ROS tau is phosphorylated!

3.4. ROS tau isoforms, at least some, were phosphorylated at the same sites as phosphorylated sites in tau isoforms associated with PHFs

Using phosphorylation site-specific antibodies we examined whether phosphorylated sites in ROS tau isoforms were identical to those in isoforms found in PHFs (Fig. 4). We chose three sites: Ser262, Ser396 and Ser404 in human tau. Phosphorylation at Ser262 attenuates the ability of tau to bind MTs [4, 10, 55–57]. Ser262 is also among the phosphorylation sites that convert tau to an inhibitory molecule that sequesters normal MT-associated proteins from MTs [25, 28]. Phosphorylation at Ser396 and Ser404 promotes self-aggregation of tau into filaments [4, 10, 55–57].

Antibodies PS262, PS396 and PS404 recognize human tau isoforms phosphorylated at Ser262, Ser396, and Ser404, respectively. We expect that these antibodies also recognize bovine tau isoforms phosphorylated at sites corresponding to these sites in human tau, i.e., Ser269, Ser403 and Ser411, for the following reasons: S269 in bovine tau is located in the peptide encoded by exon 9, and the bovine peptide is 96% homologous to the human peptide (Fig. 1). Moreover, the sequences of the Ser269-containing portion, which is composed of 26 amino acids (P256 to K281 in bovine tau, and P249 to K274 in human tau), are identical in these two species. Both Ser403 and Ser411 are located in the domain encoded by exon 13, and the domain is identical in these two species (Fig. 1).

Our results (Fig. 4) showed that phosphorylated Ser269 was detected in isoform (★5), that phosphorylated Ser403 was observed in isoforms (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10), and that phosphorylated Ser411 was detected in isoforms (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10). Phosphorylated Ser403 was also seen in tau isoform x, a tau isoform with an unknown exon combination. Phosphorylated Ser403 also appeared to be present in isoform (Δ6,8,10); however, this identification may not be conclusive because of an imprecise separation of phosphorylated isoforms. Together, we conclude that at least some ROS tau isoforms are phosphorylated at the same site(s) as phosphorylated sites in tau isoforms associated with PHFs. It is unknown now whether these ROS tau isoforms express abnormal characteristics.

We note that these three phosphorylation sites are present in domains encoded by exons 9 or 13 (Fig. 1) and that isoforms (Δ6,8,10), (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10) contain these domains. However, PS262 detected none of them (Fig. 4A), suggesting that Ser269 was not phosphorylated in these isoforms. In addition, the PS396 signal intensity of isoform (Δ3,6,8,10) was clearly less than that of isoform (Δ3,6,8) although the PS404 signal intensity of isoform (Δ3,6,8,10) appeared to be similar to that of isoform (Δ3,6,8). Moreover, PS404 did not recognize isoform (Δ6,8,10). These observations strongly suggest that these isoforms are individually phosphorylated. It is possible that conformation of these isoforms may be different from each other and that each isoform(s) may be phosphorylated by a specific kinase(s).

We also note that several faint bands were detected when PS262 was premixed with the antigen peptide (Fig. 4A). We also occasionally saw similar faint bands even when the sample was pretreated with AP. These faint bands were also observed when other phosphorylation-site specific antibodies were used on AP-pretreated isoforms. These observations imply that these antibodies, at lest some of them, may not be highly specific. However, with antibodies we chose, protein bands described here were consistently and clearly observed, and faint bands, even if detected, were not located in the position identical to that of these clear bands. Therefore, we conclude that these antibodies have a relatively higher specificity to these phosphorylated tau isoforms and are usable to identify them. We use this method because this method is convenient to identify rapidly and simultaneously an isoform when multiple phosphorylated isoforms coexist. However, in future, these phosphorylations should be further studied by using direct methods.

3.5. Solubility of ROS tau isoforms

Human brain tau is enriched in four amino acids: proline, glycine, lysine and serine. It has been reported that the high content of proline and glycine forms a random-coil conformation and that tau adopts this conformation that allows it to be a soluble protein [10, 50]. Bovine brain tau also shows the similar solubility [8, 58]. Here we examine the solubility of ROS tau isoforms by identifying isoforms in membranous and soluble fractions (Fig. 5). We found that the membranous fraction contained almost all tau-antibody-sensitive proteins, while the soluble fraction had only a single type of the protein with a MW ~40 kDa. The ~40 kDa protein also appeared to be present in the membrane fraction (Fig. 5A), suggesting that the ~40 kDa protein is originally membrane-bound; however, the binding to membranes is so weak that the protein is solubilized in part under our experimental conditions. We also found that 10–20% of tau-antibody-sensitive proteins in membranes were solubilized in a buffer containing 1% n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (Fig. 5B), while almost all these proteins were solubilized in the same buffer containing 1% of Triton X-100 (Fig. 5C). All together, it is concluded that all ROS tau isoforms are membrane-bound. This characteristic is clearly different from that of brain tau. We believe that protein (✶) (Figs. 4B and 4C) was protein (★7), but not the ~40 kDa protein, because these supernatants were obtained from membranes washed extensively. The observation suggests that binding of protein (★7) to membranes may be much sensitive to detergents than the binding of other proteins. We have already speculated that that protein (★7) may be an artifact and not be a tau-antibody-sensitive protein present originally in ROS, as described above.

We also investigated whether the binding of ROS tau-antibody-sensitive proteins to membranes was affected by their phosphorylation (Supplementary data). After suspension in Buffer A and treatment with or without AP, ROS membranes were centrifuged to obtain its supernatant and precipitate. We obtained the result identical to that shown in Figure 5A, indicating that the AP-treatment altered neither the amount nor the type of tau protein present in both fractions. We also showed that this lack of the AP effect was not due to the inactivity of AP (Supplementary data). We therefore conclude that dephosphorylation does not affect the binding of these proteins to membranes. The ~40 kDa protein appears to bind so weakly to membranes, as described above; however, the protein belongs to group a (Fig. 3A), indicating that the protein is phosphorylated. These observations also support the conclusion.

3.6. ROS tau isoforms associate, besides MTs, with a cellular component(s) in membranes

The photoreceptor contains a MT-based axoneme, which begins at the basal body in the distal portion of the inner segment, passes through the connecting cilium, and continues into the outer segment for up to 80% of its length. MTs consist of protofilaments, each made up of α/β-tubulin dimmers [59, 60]. Here, using immunogold electron microscopy, we examined the localization of tau and MTs in retinal photoreceptors (Fig. 6). When bovine preparations were used, the shape of photoreceptor sometimes appeared to be slightly collapsed. Therefore, retinas from rat and frog, but not bovine, were used to avoid the possible postmortem changes in bovine retina.

Figure 6.

Localization of tubulin α and tau in ROS. After isolation from rat and frog eyes and blocking with 4% of BSA, thin sections of retina were incubated with mouse anti-tubulin α antibody or a rabbit anti-tau antibody (final concentration 0.2 mg/ml) in PBS containing 1% BSA. These sections were rinsed with PBS, incubated on 10 or 15 nm gold-conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG and washed again with PBS. Grids were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde and washed with distilled water. Then these preparations were analyzed using an electron microscopy. Arrows indicate the MT-based axoneme. Localization of tubulin β was also examined, but the result is not shown. Scale bar, 400 nm.

We found, as expected, that tubulin α was concentrated in the axoneme in both rat and frog photoreceptors (Figs. 6Aa, Ba and Bb). Tubulin β, whether in rat or frog photoreceptors, was also observed only with the axoneme (data not shown). However, the localization of tau is clearly different from that of tubulin α/β. In the case of rat photoreceptors, the tau signal was detected in the entire outer segment (Figs. 6Ab and Ac), while almost no signal was detected with the axoneme (Fig. 6Ab). These results do not deny the possibility that a small amount of tau binds to the axoneme in rat photoreceptors; however, these results clearly show that rat tau is mainly associated with a cellular component(s) other than the axoneme in ROS. In the case of frog photoreceptors, the tau signal was also spread out the entire outer segment (Fig. 6Bc). In this case, the axoneme could not be identified, and thus, whether the frog tau was associated with the axoneme could not be determined. However, the result (Fig. 6Bc) strongly suggests that frog tau, like rat tau, is mostly associated with a cellular component(s) other than the axoneme in ROS. These observations, together with the observation showing that ROS tau is membrane-bound (Fig. 5), imply that that the cellular component is in membranes and that tau isoforms, besides the axoneme, bind to and stay with the component in ROS. The large size of frog photoreceptor results in the reduction in the signal size of both tubulin α and tau (Fig. 6B).

4. Discussion

4.1. Why do we use bovine preparations?

First, we emphasize that bovine preparations appear to be appropriate to study the mechanism of human retinal diseases that may share the mechanism of tau-mediated brain diseases. Bovine brain, like human brain, tends to develop neurofibrillary pathology [8, 61], and the primary property of bovine brain tau isoforms is similar to that of human brain isoforms. These observations suggest that tau-mediated diseases similar to those in human brain may also be developed in bovine brain. In addition, bovine retina has a structure similar to that of human retina. Thus, it can be further speculated that, similarly to the development of human brain diseases in human retina, tau-mediated bovine brain diseases may also be developed in bovine retina. Second, Cdk5, one of the protein kinases responsible for the hyperphosphorylation of human brain tau, is present in bovine retina including ROS [31, 32]. Third, large quantities of bovine preparations are available. Bovine ROS is the only retinal portion that can be obtained in large quantities and purified now. The purity of our ROS preparation is at least more than 90% [43, 44].

Followings are not limited to bovine preparations; however, they are worthy of special mention: First, the tau interaction with MTs can be easily estimated in retinal photoreceptor in situ because of localization of MTs in the axoneme in photoreceptors [59, 60]. Second, an enormous amount of information about ROS biochemistry, cell biology and physiology is available [62, 63]. Finally, we emphasize that ROS is a part of a retinal cell and that the study of ROS tau may reveal the actual behavior of tau in a single type of retinal cells. Previous studies about retinal tau were based on the tau derived from the whole retina. Retina contains various types of cells. Thus, previous observations may blur cellular differences and not reflect the actual tau behavior in a retinal cell.

4.2. Is ROS tau composed of isoforms identical to those of brain tau?

We have shown that bovine ROS contains four isoforms as major tau isoforms: (Δ6,8,10), (Δ3,6,8), (Δ3,6,8,10) and (★5) (Fig. 2). The first three isoforms are also found in brain (Fig. 1). We also found that some of other ROS proteins showed migration profiles identical to those of brain proteins although the amount of these proteins was negligible. These observations support in part the view that ROS tau is composed of isoforms identical of brain tau. However, we also note that the level of isoform (Δ6,8), one of major isoforms in brain, is negligible in ROS and that ROS specifically contains isoform (★5) as a major tau isoform (Fig. 2). These indicate that the combination of ROS tau isoforms (or retinal isoforms) is distinct from that of brain tau. In addition, we emphasize that ROS (or a single type of retinal cell) contains so many different tau isoforms. It is likely that tau has various functions in ROS and that some of these functions may be ROS-specific. These observations do not deny the possibility that a certain type of cells in the brain may have a combination of tau isoforms identical to those in ROS, and that these isoforms may have functions similar to those of ROS isoforms. However, the protein identical to isoform (★5) was negligible in the brain (Fig. 2), implying that these cells may not be abundant in brain tissue. We therefore conclude that ROS tau has a unique set of isoforms and that studying of tau in both the entire retina and individual retinal cells is also crucial to reveal the mechanism of tau-mediated retinal diseases.

4.3. Is ROS tau phosphorylated similarly to brain tau?

Normal human brain tau is phosphorylated with multiple phosphate molecules [21], implying that tau in bovine brain is also modified with multiple phosphate molecules. Here we have suggested that ROS tau isoforms are also modified with multiple phosphate molecules and thus both brain and ROS tau may be regulated in a similar manner. However, we emphasize that some ROS tau isoforms are also phosphorylated in a specific manner. For example, ROS tau isoforms, especially isoforms with high MWs, appear to be highly phosphorylated (Figs. 2 and 5); however, brain isoforms are not (Fig. 2). We also found that some ROS tau isoforms, even isoforms obtained from normal retinas, were phosphorylated at the sites identical to those in PHFs, implying that phosphorylation of ROS tau appears to be specific to each isoform. (Fig. 4). These observations suggest that some ROS tau isoforms are uniquely phosphorylated and that these modifications may be required for normal function of ROS tau. A simple application of the information about brain tau phosphorylation may be inappropriate to explain phosphorylation of tau in ROS (or in other individual retinal cells) and retina.

The phosphorylation status of ROS tau was estimated by the change of its migration profile by AP treatment and detection by antibodies (Figs. 2, 3 and 5), because this procedure is suitable to examine the phosphorylation status of all tau isoforms swiftly and simultaneously under the same conditions. The specificity of the antibody regularly used, Dako rabbit anti-human tau antibody, was confirmed when tau localization in ROS was investigated (Fig. 6). However, this procedure is not straightforward. In addition, phosphorylation site-specific antibodies may not be highly specific, as described above. Thus, observations in experiments using antibodies should also be further investigated by using direct methods such as identification of phosphorylated sites by proteomics, direct incorporation of [32P] into a specific tau isoform by a specific kinase(s), and phosphorylation of site-specific tau mutant forms.

4.5 Does ROS tau bind to MTs in the same manner as brain tau does?

This question is a crucial for tau. Thus, we started this study by asking a basic question: whether ROS tau is soluble or membrane-bound. Bovine brain tau has been reported to be soluble [8, 58]. However, bovine ROS tau isoforms, even isoforms having the same structures as those of brain isoforms, were membrane-bound (Figs. 3 and 5). ROS tau might bind to and stay with MTs and thus appear to be membrane-bound. However, tubulins α/β are concentrated in the axoneme in photoreceptors, but tau is detected in the entire outer segment (Fig. 6). These results indicate that a great part of ROS tau associates with a cellular component(s) other than MTs and that the association results in the tight binding of ROS tau to membranes. Dephosphorylation did not affect the solubility of ROS tau (Supplementary data), suggesting that phosphorylation is not primarily involved in the tau association with the component. These observations do not deny the possibility that a small amount of tau binds to the axoneme in photoreceptors; however, these observations clearly show the uniqueness of ROS tau.

The apparent MWs of brain tau isoforms are much higher than their calculated MWs (Figs. 1 and 2). This phenomenon has been explained by their hydrophilicity [10, 50]. ROS tau isoforms migrate on the SDS-gel in the same manner as brain tau does, but ROS proteins are membrane-bound (Fig. 5). We believe that the increase in the apparent MW of ROS tau isoforms does not directly link to their hydrophilicity, because the hydrophilicity is a property of a native protein, but not a denatured protein, and this study obtained the apparent MW of ROS tau after heating it in a SDS-containing sample buffer. We believe that the denatured form of ROS tau has a tendency to make a large micelle with a large number of SDS molecule under the conditions that the stoichiometry of SDS bound to tau isoforms is relatively uniform. Therefore, apparent MWs of tau isoforms appear to be substantially proportional to calculated MWs, but appear to be much higher than their calculated MWs. We note that running profiles of ROS isoforms (Δ6,8,10) and (Δ3,6,8) did not follow their calculated MWs (Fig. 2). This inconsistency may also be due to a difference in the size of micelles formed by these tau isoforms and SDS molecules, and the domain encoded by exon 3 and/or 10 may be crucial for binding of SDS. Phosphate molecules attached to isoforms increase their apparent MWs. However, the increase appear to be trivial because apparent MWs of isoforms (Δ3,6,8), (Δ3,6,8,10) and (★5) appeared not to be altered by the AP treatment (Figs. 2 and 5).

4.6 Is the cellular component crucial for ROS tau?

The cellular component is not identified in this study. However, it is likely that the component affects both function and regulation of ROS tau, because introduction of the component makes it much easier to explain behavior of ROS tau. For example, ROS tau isoforms having high apparent MWs, but not brain isoforms, were clearly detected and separated only when they were pretreated with AP (Figs. 2 and 5). In this study, we interpret these observations as given below: All ROS tau isoforms have been phosphorylated; however, the phosphorylation level of isoforms with high apparent MWs is much higher than that of other isoforms, and thus these isoforms diffuse on a SDS-gel. In the case of brain isoform, these isoforms may not be phosphorylated or if phosphorylated, their phosphorylation levels may be much less that those of ROS isoforms, and thus, these brain isoforms, whether phosphorylated or not phosphorylated, are concentrated on the SDS-gel. Two problems rise in the explanation: (1) If only ROS tau isoforms are phosphorylated, our explanations do not address why only ROS isoforms are phosphorylated, and (2) if both ROS and brain tau isoforms are phosphorylated, our explanations do not address why only ROS isoforms with high apparent MWs show the phenomenon. However, with the cellular component, these problems may be explained as follows: (a) ROS isoforms, but not brain isoforms, make complexes with components and thus only ROS isoforms are phosphorylated, and (b) ROS isoforms with high MWs make complexes with specific components and thus the phosphorylation level of these isoforms are much higher. We note that explanation 1 is based on the fact that the phosphorylation pattern of bovine brain tau is not clearly known. However, bovine brain tau, like human brain tau, may be modified with multiple phosphate molecules, because structure of bovine brain tau is similar to that of human tau (Fig. 1). Therefore, explanation 1 may be excluded. We have also shown that AP treatment significantly reduces the amount of ROS isoform (Δ6,8,10) under the conditions that amounts of isoforms (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10) are not changed (Figs. 2A and 5A). We have explained the phenomenon as given below: Dephosphorylation of isoform (Δ6,8,10) would change its conformation, and the change would increase its sensitivity to a proteinase(s). However, the AP treatment appears not to reduce the level of brain isoform (Δ6,8,10) (Fig. 2A). Thus, our explanation may not interpret the difference between ROS tau and brain tau. However, with the cellular component, the difference may be explained as follows: ROS isoform (Δ6,8,10), even after dephosphorylation, still keeps its complex with the component (Supplementary data), and only the isoform associated with the component has a high sensitivity to a specific proteinase. Together, these speculations may imply that the cellular component has an important role(s) in regulation and function of ROS tau. Identification of the component and its characterization are urgent.

4.7. Does ROS tau play a role in phototransduction?

Accumulating evidence suggests that tau, in addition to MTs, interacts with various cellular components [4, 10, 64]. This study also shows that a large part of ROS tau interacts with cellular components other than MTs (Fig. 6), implying that ROS tau may have a function other than the interaction with MTs. The function has not been yet studied, because we have focused to examine collectively the current view that tau-mediated retinal degenerative diseases can be explained by using knowledge of tau-mediated diseases in brain, and because the examination, we believe, is important for the progress in the study of tau-mediated retinal diseases. We only speculate, as the function, that ROS tau may be involved in phototransduction, because ROS is the site for phototransduction and the failure of phototransduction causes retina degeneration. ROS tau may be associated with a protein(s) involved in phototransduction and the proteinprotein interaction may be disrupted by hyperphosphorylation of tau. We have shown that Cdk5 phosphorylates Pγ, the inhibitory subunit of cGMP phosphodiesterase (EC 3.1.4.35) (PDE), when rhodopsin is illuminated, i.e., when Pγ is complexed with GTP-Tα (GTP-bound form of the α subunit of retinal G protein), and that PDE function may be altered [31, 65, 66]. Interestingly, tau, like Pγ, has the sequence required for phosphorylation by Cdk5 (S411-P412-R413 in bovine tau) and phosphorylated Ser411 was indeed found in tau isoforms (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10) (Fig. 4C). It is possible that Cdk5 may phosphorylate Ser411 in these tau isoforms and that, with phosphorylation of other sites, function of these tau isoforms in phototransduction may be disrupted. GTP-Tα, similarly to Pγ phosphorylation, may also be involved in the phosphorylation of Ser411. If so, this model is clearly different from the current model for phototransduction. We also expect that the phosphorylation, if any, may be induced only after interaction of isoforms (Δ3,6,8) and (Δ3,6,8,10) with a cellular component(s) specific to these isoforms, because phosphorylated Ser411 is not found in isoform (Δ6,8,10) even though the isoform contains the site (Fig. 4C). In any case, it is of great interest to evaluate the effect of proteins involved in phototransduction on tau regulation or vice versa.

4.8. Conclusion

We show that ROS has a unique combination of tau isoforms and that regulation of these isoforms is not always comparable to those in brain tau. We also suggest that ROS tau associates with, besides the MT-based axoneme, other membranous component(s) and that the interaction may be crucial for its function and regulation. Some of these conclusions are based on indirect observations, and thus further studies are needed. However, observations described here are clear. Thus, we propose that knowledge about tau in the entire retina and/or in individual retinal cells should also be clarified and taken into consideration in the study of tau-mediated retinal diseases.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Bovine retinal photoreceptor tau consists of at least four isoforms.

Retinal photoreceptor tau isoforms are modified with multiple phosphate molecules.

Most of retinal photoreceptor tau interacts with components other than microtubules.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hanayo Honkawa for preliminary work during her tenure at Wayne State University. We also thank Dr. Richard B. Needleman (Wayne State University) for critical reading. This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Health EY09631 (to AY), a grant from National Health Research Institute MG-099-PP-09 (to IM), a grant from National Research Program for Biopharmaceuticals 101HD1006 (to IM), a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 22370056 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (to JU) and an unrestricted grant from College of Osteopathic Medicine, Touro University Nevada (to VB).

Abbreviations

- AP

alkaline phosphatase

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- Cdk5

cyclin-dependent protein kinase 5

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- FTDP-17

front-temporal dementia with parkinsonism liked to chromosome

- MT

microtubule

- MW

molecular weight

- PHF

paired helical filament

- pI

isoelectric point

- PMSF

phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride

- Pγ

the inhibitory subunit of cGMP phosphodiesterase

- PDE

cGMP phosphodiesterase

- ROS

rod outer segments of retinal photoreceptors

- Tα

the α subunit of retinal G protein

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Drubin DG, Feinstein SC, Shooter EM, Kirschner MW. Nerve growth factor-induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells involves the coordinate induction of microtubule assembly and assembly-promoting factors. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:1799–17807. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.5.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goedert M, Crowther RA, Garner CC. Molecular characterization of microtubule-associated proteins tau and MAP2. Trends Neurosci. 1991;14:193–199. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stamer K, Vogel R, Thies E, Mandelkow E, Mandelkow EM. Tau blocks traffic of organelles, neurofilaments, and APP vesicles in neurons and enhances oxidative stress. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:1051–1063. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buée L, Bussière T, Buée-Scherrer V, Delacourte A, Hof PR. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;33:95–130. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee VM, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1121–1159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taipa R, Pinho J, Melo-Pires M. Clinico-pathological correlations of the most common neurodegenerative dementias. Front Neurol. 2012;3:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Himmler A. Structure of the bovine tau gene: alternatively spliced transcripts generate a protein family. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1389–1396. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janke C, Beck M, Stahl T, Holzer M, Brauer K, Bigl V, Arendt T. Phylogenetic diversity of the expression of the microtubule-associated protein tau: implications for neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1999;68:119–128. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(99)00079-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goode BL, Chau M, Denis PE, Feinstein SC. Structural and functional differences between 3-repeat and 4-repeat tau isoforms, Implications for normal tau function and the onset of neurodegenetative disease. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38182–38189. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chun W, Johnson GV. The role of tau phosphorylation and cleavage in neuronal cell death. Front Biosci. 2007;12:733–756. doi: 10.2741/2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Cairns NJ, Crowther RA. Tau proteins of Alzheimer paired helical filaments: abnormal phosphorylation of all six brain isoforms. Neuron. 1992;8:159–168. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(92)90117-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goedert M. Tau protein and the neurofibrillary pathology of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:460–465. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90078-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Spillantini MG, Murrell JR, Goedert M, Farlow MR, Klug A, Ghetti B. Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:7737–7741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sergeant N, David JP, Lefranc D, Vermersch P, Wattez A, Delacourte A. Different distribution of phosphorylated tau protein isoforms in Alzheimer’s and Pick’s diseases. FEBS Lett. 1997;412:578–582. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00859-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delacourte A, Sergeant N, Wattez A, Gauvreau D, Robitaille Y. Vulnerable neuronal subsets in Alzheimer’s and Pick’s disease are distinguished by their tau isoform distribution and phosphorylation. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:193–204. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reiniger L, Lukic A, Linehan J, Rudge P, Collinge J, Mead S, Brandner S. Tau, prions and Aβ: the triad of neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2011;121:5–20. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0691-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morishima-Kawashima M, Hasegawa M, Takio K, Suzuki M, Yoshida H, Titani K, Ihara Y. Proline-directed and non-proline-directed phosphorylation of PHF-tau. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:823–829. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.2.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanger DP, Betts JC, Loviny TL, Blackstock WP, Anderton BH. New phosphorylation sites identified in hyperphosphorylated tau (paired helical filament-tau) from Alzheimer’s disease brain using nanoelectrospray mass spectrometry. J Neurochem. 1998;71:2465–2476. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71062465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong CX, Liu F, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Dysregulation of protein phosphorylation/dephosphorylation in Alzheimer’s disease: a therapeutic target. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2006;2006:1–11. doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/31825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanger DP, Byers HL, Wray S, Leung KY, Saxton MJ, Seereeram A, Reynolds CH, Ward MA, Anderton BH. Novel phosphorylation sites in tau from Alzheimer brain support a role for casein kinase 1 in disease pathogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:23645–23654. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang JZ, Xia YY, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Abnormal hyperphosphorylation of tau: sites, regualtion, and molecualr mechanism of neurofibrillary degeneration. J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;33:S123–S139. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-129031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kenessey A, Yen SH. The extent of phosphorylation of fetal tau is comparable to that of PHF-tau from Alzheimer paired helical filaments. Brain Res. 1993;629:40–46. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)90478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang JZ, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Kinases and phosphatases and tau sites involved in Alzheimer neurofibrillary degeneration. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:59–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Delacourte A, Buée L. Normal and pathological Tau proteins as factors for microtubule assembly. Int Rev Cytol. 1997;171:167–224. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62588-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levy SF, Leboeuf AC, Massie MR, Jordan MA, Wilson L, Feinstein SC. Three- and four-repeat tau regulate the dynamic instability of two distinct microtubule subpopulations in qualitatively different manners. Implications for neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13520–13528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong M, Zhukareva V, Vogelsberg-Ragaglia V, Wszolek Z, Reed L, Miller BI, Geschwind DH, Bird TD, McKeel D, Goate A, Morris JC, Wilhelmsen KC, Schellenberg GD, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VM. Mutation-specific functional impairments in distinct tau isoforms of hereditary FTDP-17. Science. 1998;282:1914–1917. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gamblin TC, King ME, Dawson H, Vitek MP, Kuret J, Berry RW, Binder LI. In vitro polymerization of tau protein monitored by laser light scattering: method and application to the study of FTDP-17 mutants. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6136–6144. doi: 10.1021/bi000201f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jordan MA, Wilson L. Microtubules as a target for anticancer drugs. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:253–265. doi: 10.1038/nrc1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tucker RP, Matus AI. Microtubule-associated proteins characteristic of embryonic brain are found in the adult mammalian retina. Dev Biol. 1988;130:423–434. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90338-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loffler KU, Edward DP, Tso MO. Immunoreactivity against tau, amyloid precursor protein, and beta-amyloid in the human retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1995;36:24–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayashi F, Matsuura I, Kachi S, Maeda T, Yamamoto M, Fujii Y, Liu H, Yamazaki M, Usukura J, Yamazaki A. Phosphorylation by cyclin-dependent protein kinase 5 of the regulatory subunit of retinal cGMP phosphodiesterase, II, Its role in the turnoff of phosphodiesterase in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32958–32965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000703200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saturno G, Pesenti M, Cavazzoli C, Rossi A, Giusti AM, Gierke B, Pawlak M, Venturi M. Expression of serine/threonine protein-kinases and related factors in normal monkey and human retinas: the mechanistic understanding of a CDK2 inhibitor induced retinal toxicity. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:972–983. doi: 10.1080/01926230701748271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bayer AU, Ferrari F, Erb C. High occurrence rate of glaucoma among patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Neurol. 2002;47:165–168. doi: 10.1159/000047976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoneda S, Hara H, Hirata A, Fukushima M, Inomata Y, Tanihara H. Vitreous fluid levels of beta-amyloid (1–42) and tau in patients with retinal diseases. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005;49:106–108. doi: 10.1007/s10384-004-0156-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura H, Kawakami H, Kanamoto T, Kato T, Yokoyama T, Sasaki K, Izumi Y, Matsumoto M, Mishima HK. High frequency of open-angle glaucoma in Japanese patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2006;246:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gupta N, Fong J, Ang LC, Yücel YH. Retinal tau pathology in human glaucomas. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008;43:53–60. doi: 10.3129/i07-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wostyn P, Audenaert K, De Deyn PP. Alzheimer’s disease-related changes in diseases characterized by elevation of intracranial or intraocular pressure. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guo L, Duggan J, Cordeiro MF. Alzheimer’s disease and retinal neurodegeneration. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010;7:3–14. doi: 10.2174/156720510790274491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leger F, Fernagut PO, Canron MH, Léoni S, Vital C, Tison F, Bezard E, Vital A. Protein aggregation in the aging retina. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2011;70:63–68. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31820376cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parnell M, Guo L, Abdi M, Cordeiro MF. Ocular manifestations of Alzheimer’s disease in animal models. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2012/786494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ho WL, Leung Y, Tsang AWT, So KF, Chiu K, Chang RCC. Taupathy in the retina and opitic nerve: does it shadow pathological changes in the brain? Mol Vis. 2012;18:2700–2710. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yamazaki A, Bitensky MW, Casnellie JE. Photoaffinity labeling of high-affinity cGMP-specific noncatalytic binding sites on cGMP phosphodiesterase of rod outer segments. Methods Enzymol. 1988;159:730–736. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)59068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamazaki A, Yamazaki M, Yamazaki RK, Usukura J. Illuminated rhodopsin is required for strong activation of retinal guanylate cyclase by guanylate cyclase-activating proteins. Biochemistry. 2006;45:1899–1909. doi: 10.1021/bi0519396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamazaki A, Tatsumi M, Torney DC, Bitensky MW. The GTP-binding protein of rod outer segments, I, Role of each subunit in the GTP hydrolytic cycle. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:9316–9323. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamazaki A, Tatsumi M, Bondarenko VA, Kurono S, Komori N, Matsumoto H, Matsuura I, Hayashi F, Yamazaki RK, Usukura J. Mechanism for the regulation of mammalian cGMP phosphodiesterase6, 2, isolation and characterization of the transducin-activated form. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;339:235–251. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0404-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kachi S, Yamazaki A, Usukura J. Localization of caveolin-1 in photoreceptor synaptic ribbons. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:850–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Himmler A, Drechsel D, Kirschner MW, Martin DW., Jr Tau consists of a set of proteins with repeated C-terminal microtubule-binding domains and variable N-terminal domains. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1381–1388. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.4.1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen WT, Liu WK, Yen SH. Expression of tau exon 8 in different species. Neurosci Lett. 1994;172:167–170. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90688-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baudier J, Lee SH, Cole RD. Separation of the different microtubule-associated tau protein species from bovine brain and their mode II phosphorylation by Ca2+/phospholipid-dependent protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:17584–17590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hernandez F, Pèrez M, de Barreda EG, Goñi-Oliver P, Avila J. Tau as a molecular marker of development, aging and neurodegenerative disorders. Curr Aging Sci. 2008;1:56–61. doi: 10.2174/1874609810801010056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goedert M, Jakes R. Expression of separate isoforms of human tau protein: correlation with the tau pattern in brain and effects on tubulin polymerization. EMBO J. 1990;9:4225–30. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07870.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sontag E, Nunbhakdi-Craig V, Lee G, Brandt R, Kamibayashi C, Kuret J, White CL, III, Mumby MC, Bloom GS. Molecular interactions among protein phosphatase 2A, tau, and microtubules, Implications for the regulation of tau phosphorylation and the development of tauopathies. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25490–25498. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Palczewski K, Hargrave PA, McDowell JH, Ingebritsen TS. The catalytic subunit of phosphatase 2A dephosphorylates phosphoopsin. Biochemistry. 1989;28:415–419. doi: 10.1021/bi00428a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.King AJ, Andjelkovic N, Hemmings BA, Akhtar M. The phospho-opsin phosphatase from bovine rod outer segments, An insight into the mechanism of stimulation of type-2A protein phosphatase activity by protamine. Eur J Biochem. 1994;225:383–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferrer I, Gomez-Isla T, Puig B, Freixes M, Ribé E, Dalfó E, Avila J. Current advances on different kinases involved in tau phosphorylation, and implications in Alzheimer’s disease and tauopathies. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2005;2:3–18. doi: 10.2174/1567205052772713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alonso AD, Di Clerico J, Li B, Corbo CP, Alaniz ME, Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K. Phosphorylation of tau at Thr212, Thr231, and Ser262 combined causes neurodegeneration. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:30851–30860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.110957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kiris E, Ventimiglia D, Sargin ME, Gaylord MR, Altinok A, Rose K, Manjunath BS, Jordan MA, Wilson L, Feinstein SC. Combinatorial Tau pseudophosphorylation: markedly different regulatory effects on microtubule assembly and dynamic instability than the sum of the individual parts. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:14257–14270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.219311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Volke D, Hoffmann R. Purification of bovine Tau versions by affinity chromatography. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;50:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rohlich P. The sensory cilium of retinal rods is analogous to the transitional zone of motile cilia. Cell Tissue Res. 1975;161:421–30. doi: 10.1007/BF00220009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kaplan MW, Iwata RT, Sears RC. Lengths of immunolabeled ciliary microtubules in frog photoreceptor outer segments. Exp Eye Res. 1987;44:623–32. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(87)80134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nelson PT, Stefansson K, Gulcher J, Saper CB. Molecular evolution of tau protein: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 1996;67:1622–1632. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67041622.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller WH. Dark mimic. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:1659–1673. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burns ME, Baylor DA. Activation, deactivation, and adaptation in vertebrate photoreceptor cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:779–805. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dehmelt L, Halpain S. The MAP2/Tau family of microtubule-associated proteins. Genome Biol. 2005;6:204–213. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-6-1-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matuura I, Bondarenko VA, Maeda T, Kachi S, Yamazaki M, Usukura J, Hayashi F, Yamazaki A. Phosphorylation by cyclin-dependent protein kinase 5 of the regulatory subunit of retinal cGMP phosphodiesterase, I, Identification of the kinase and its role in the turnoff of phosphodiesterase in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:32950–32957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000702200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamazaki A, Moskvin O, Yamazaki RK. Phosphorylation by cyclin-dependent protein kinase 5 of the regulatory subunit (Pγ) of retinal cGMP phosphodiesterase (PDE6): Its implications in phototransduction. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;514:131–153. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0121-3_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.