Abstract

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) 2006 report, From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition (In M. Hewitt, S. Greenfield and E. Stovall (Eds.), (pp. 9–186). Washington DC: The National Academies Press, 2006) identifies the key components of care that contribute to quality of life for the cancer survivor. As cancer survivorship care becomes an important part of quality cancer care oncology professionals need education to prepare themselves to provide this care. Survivorship care requires a varied approach depending on the survivor population, treatment regimens and care settings. The goal of this program was to encourage institutional changes that would integrate survivorship care into participating centers. An NCI-funded educational program: Survivorship Education for Quality Cancer Care provided multidiscipline two-person teams an opportunity to gain this important knowledge using a goal-directed, team approach. Educational programs were funded for yearly courses from 2006 to 2009. Survivorship care curriculum was developed using the Quality of Life Model as the core around the IOM recommendations. Baseline data was collected for all participants. Teams were followed-up at 6, 12 and 18 months postcourse for goal achievement and institutional evaluations. Comparison data from baseline to 18 months provided information on the 204 multidiscipline teams that participated over 4 years. Teams attended including administrators, social workers, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, physicians and others. Participating centers included primarily community cancer centers and academic centers followed by pediatric centers, ambulatory/physician offices and free standing cancer centers. Statistically significant changes at p=<0.05 levels were seen by 12 months postcourse related to the effectiveness, receptiveness and comfort of survivorship care in participant settings. Institutional assessments found improvement in seven domains of care that related to institutional change. This course provided education to participants that led to significant changes in survivorship care in their settings.

Keywords: Cancer survivorship education, Institutional change, Quality of life, Institutional survey, Institutional assessment

Introduction

Cancer survivorship care is an emerging and a necessary component of oncology care. Cancer survivors are increasing with over 12 million expected by 2020 (Surveillance Epidemiology and [24] released). Cancer survivors' needs vary dependent upon differences in diseases and treatments and result in long-term consequences to their health and well-being. For example, breast cancer patients who have been treated with anthracyclines may be at an increased risk for cardiac complications in the future, lymphoma survivors risk cardiovascular changes, colorectal cancer patients experience neuropathy and prostate cancer patients may deal with erectile dysfunction [5,16]. All survivors deal with psychosocial issues, fatigue and risks for recurrence or the development of new cancers [6]. Meeting the varied needs of cancer survivors involves institutional changes in survivorship care. Such changes begin with educating health care professionals on the components of survivorship care and recommendations to meet the long-term and late effects cancer patients experience [9]. This article reports on the NCI-funded program: Survivorship Education for Quality Cancer Care.

Background

Research has demonstrated that cancer survivors do not return to prediagnosis status [22]. Cancer survivors experience long-term and late effects of their diagnosis and treatments that combined with comorbidities as they age, impact their quality of life and affect their families and caregivers as well [14,17,25,26]. LiveSTRONG's survey of cancer survivors revealed a lack of support from health care providers resulting in 59% of cancer survivors learning to live with their side effects and 41% taking it upon themselves to try to find the care they needed [21]. Finding appropriate medical care follow-up for patients and their families will require changes in the way care is provided [12,23]. Assisting cancer settings across the nation in providing this care requires staff education and support to help meet this challenge and change institutional priorities. Integrating this care into oncology practice will be necessary to provide the quality of care desired for the cancer survivor.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report [12] provides a key resource for the elements of survivorship care. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition provides a template for the four essential elements of survivorship care: prevention and detection, surveillance, interventions to manage side effects, and coordination of care and information [12]. Survivorship care requires interdisciplinary care, that is, staff from many disciplines work together to meet the needs of the cancer patient. Cancer survivors need coordinated care specific to their individual needs. This care may continue to be organized by the oncology staff or be shifted to the Primary Care Provider (PCP) [15]. Management strategies require physicians, advanced practice nurses, nurses, social workers, psychosocial specialists, rehabilitation, administrators and community resource agencies to work together to provide the orchestrated care necessary to meet those needs. Educating health care professionals on how best to meet the needs of this growing body of patients is essential.

Approximately 5,008 community hospitals in the United States account for 35,527,377 admissions yearly [3]. Almost 85% of cancer patients are cared for in these community hospitals, with academic cancer centers and free-standing cancer centers providing care for the rest of the patients [3]. Within all cancer settings there is a looming health care provider shortage of physicians and nurses that will have a significant impact on the ability to provide care to the growing numbers of cancer survivors [1,4]. The catalyst for the program reported here was recognizing that cancer survivors need support throughout the trajectory of care from diagnosis and continuing throughout their life. Educating health care providers from cancer centers to integrate the components of survivorship care into their practice is essential to meet the growing needs of this population.

Program Aims

Survivorship Education for Quality Cancer Care was designed to provide health care professionals with training to improve quality of care and quality of life for cancer survivors. Project aims included to:

Create the cancer survivorship curriculum for training an interdisciplinary professional audience from cancer centers. Professional audience will include nurses, physicians and administrators as a first tier, and social workers, clergy, pharmacists, psychologists and rehabilitation professionals as a second tier.

Implement the survivorship curriculum in national workshops to competitively selected staff from the National Cancer Institute-designated clinical and comprehensive cancer centers, and community cancer centers as identified through the Association of Community Cancer Centers (ACCC).

Develop a network of course participants to share experiences in dissemination of the survivorship curriculum to the staff of participating cancer centers.

Evaluate the impact of the survivorship curriculum on participants' and cancer center staffs' implementation of individual goals for improved care for cancer survivors in respective cancer centers.

Describe successes and issues related to dissemination of cancer survivorship care in cancer centers in terms of the characteristics of individual course participants, interdisciplinary teams and institutions.

Curriculum Framework and Course Content

Expert faculty from across the country participated in the development and delivery of the curriculum [10]. Institutional change theory and adult learning principles were used to help prepare participants to make meaningful changes in survivorship care in their individual settings.

Using the Quality of Life Model for Cancer Survivors, the curriculum was built around the four domains: physical, psychological, social and spiritual [8]. The State of the Science was included for each domain and faculty members from settings of excellence in survivorship care were invited to present the evidence-based content. Other topics included an overview of issues and trends in survivorship care, needs of pediatric and adolescent/young adult populations (Table 1). Breakout sessions were planned to provide small group interaction and encourage group discussions. These groups addressed topics related to the survivorship movement, and survivors' perspectives, community support and starting a survivorship clinic. Both research needs and institutional change principles were used to help focus content that could be used in individual participant's settings.

Table 1. Course content.

| Survivorship curriculum: Survivorship Education for Quality Cancer Care |

|---|

| Welcome and overview of survivorship care |

| Cancer survivorship issues and trends |

| Living beyond cancer: making survivorship part of the continuum of care |

| Health-related outcomes after pediatric cancer: price of cure |

| Survivorship issues for adolescents and young adults |

| Physical component |

| State of the Science—physical well-being and survivorship |

| Psychological component |

| State of the Science—psychological well-being and survivorship |

| Breakouts |

| National Coalition of Cancer Survivors (NCCS) and survivorship movement |

| Current perspectives from a cancer survivor |

| A model of excellence in community cancer support |

| Starting a survivorship clinic |

| A survivor's perspective |

| Social component |

| State of the Science—social well-being and survivorship |

| Spiritual component |

| State of thes—spirituality and survivorship |

| NCI: the Office of Cancer Survivorship: research agenda and findings |

| Institutional change and support opportunities for survivorship programs |

| Goal refinement/evaluation |

Course Description

A two and a half day course was developed. The program started with a welcome reception to begin participant and faculty networking. Selections from the Lilly Oncology on Canvas art exhibit were on display to encourage socializing. Also available were resources on survivorship care that participants could look at, take or evaluate and consider ordering for their own institutions. Time was allotted for participants to talk with faculty and discuss how they planned to change survivorship care in their own institutions.

Teams/Participants

Four yearly training courses for multidisciplinary, two-person teams that were competitively chosen from cancer settings across the nation attended. Potential teams were assessed using an evaluation form developed for this course that appraised participant support and motivation to attend. Past experience with survivorship care was documented and three goals on what actions participants anticipated when they returned to their institutions were part of the application. These were discussed as part of the course and refined to identify the focus of the team and realistic plans. Team members were required to include one member from Tier One which had to be a physician, nurse, social worker or administrator and the second team member from Tier Two that included any other professional who would help achieve team goals. Tier One participants were selected from these disciplines in anticipation of their ability to implement institutional changes. Courses were limited to 50 teams per course. Settings selected included academic, community-based, physician offices and supportive care centers. A few second teams from previously attended settings were accepted in later courses in an effort to help these settings achieve their goals by expanding the numbers of educated colleagues in survivorship care to support their activities.

Evaluation Methods

Evaluation methods included were a mixed methods approach with both quantitative and qualitative data. Applications were evaluated based on geography, ethnicities, populations served and applicant characteristics. Geography of the centers applying and institutional characteristics were evaluated in an effort to include a broad range of cancer survivor populations. Participant evaluation included professional background and previous experiences related to cancer survivorship. Administrator letters of support were required and evaluated for enthusiasm and support of survivorship activities from an institutional point of view.

Postcourse telephone interviews were conducted at 6, 12 and 18 months to evaluate goal progress and provide motivation and problem solving support. Additional evaluations targeted individual and institutional assessments conducted at baseline, 12 and 18 months. These provided a quantitative method of evaluating the domains of survivorship care provided within each participating setting and measured change over the 18 months postcourse.

An institutional survey focused on staff characteristics at each setting. It was completed by each team at baseline, 6, 12 and 18 months postcourse and included seven questions with five questions rated on a 0–10 scale with 10 being the most positive. These questions, rated by team members, evaluated settings for effectiveness of survivorship care, how comfortable staff was in caring for cancer survivors, how receptive were they in improving survivorship care and how supportive administration was towards improving cancer survivorship care. The survey also included identifying general barriers to improving survivorship care: administrative support, lack of survivorship knowledge, staff philosophy about survivorship and financial constraints. The influence of this course on changes that occurred in their settings regarding survivorship care was also rated.

The institutional assessment was collected at baseline, 12 and 18 months postcourse. It focused on broad characteristics of the participant setting. It evaluated aspects of survivorship care within seven domains: vision and management standards, practice standards, psychosocial and emotional standards, communication standards, quality improvement standards, patient and family education postcancer treatment and community network and partnerships. Items were rated as present/not present. Each domain included several specific items relating to the theme. The institutional survey and assessment tools were adapted from instruments used in the investigators previous programs (Grant et al. [11]).

Course and faculty evaluations were collected each day for each course. Course evaluations were rated on a 1–5 scale with 5 = excellent. Each year, these evaluations were used to further refine the curriculum and assist faculty with updating their course materials.

A key component of evaluation included goal activity, rated at 6, 12 and 18 months for percent of achievement and content. General goal achievements will be discussed here; detailed reports on goal content will be discussed in future publications.

Results

Team Demographics

Two hundred and four multidisciplinary teams participated in four annual courses for 2006–2009 (Table 2). Forty-four states were represented as well as two teams of auditors from Canada. Team composition represented a variety of disciplines primarily, nurses, social workers and administrators. Teams came from a wide range of cancer settings. Thirty of the participating teams were from NCI-designated cancer centers with six from NCI-designated clinical centers and 24 from NCI Comprehensive Cancer Centers. Ethnicity of participants was primarily Caucasian but populations that served in their cancer settings were more diverse. They include: 71.2% Caucasian, African American accounted for 11.2%, Hispanic/Latino 10%, Asian/Pacific Islander 3.4%, American Indian/Alaskan 2% and other 2.2%.

Table 2. Teams, participant and course characteristics for 2006–2009.

| Number | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants (N=408) | ||

| Administrators | 131 | 32 |

| Social workers | 66 | 16 |

| Nurse practitioners | 59 | 15 |

| Registered nurses | 57 | 14 |

| Physicians | 36 | 9 |

| Clinical nurse specialist | 34 | 8 |

| PhD | 13 | 3 |

| Others | 12 | 3 |

| Institutional setting (N=204) | ||

| Community cancer centers | 133 | 65 |

| Academic centers | 54 | 27 |

| Pediatric center | 9 | 4 |

| Ambulatory/physician offices | 4 | 2 |

| Free-standing cancer centers | 4 | 2 |

| Course evaluations (N=408) | Mean | Range |

| Overall opinion | 4.8 | 6.6–5.0 |

| Stimulating information | 4.8 | 3.4–5.0 |

| Objectives met | 4.1 | 4.4–5.0 |

| Faculty clarity | 4.7 | 4.4–4.9 |

| Quality of content | 4.7 | 3.8–4.9 |

| Content value | 4.5 | 3.8–5.0 |

Course and faculty evaluations were consistently high across all 4 years (Table 2). Faculty was available throughout and following the course to all participants for consultation as needed. Some participants commented on overall quality of the course and stated that it was well-planned and well-provided. Some participants stated that it was the best course they ever attended.

Over the 4 years' participation in follow-up, evaluations remained high. Percentage of participant providing institutional follow-up at 6 months over the 4 years averaged 86% and ranged from 75% to 98%. Twelve-month follow-up over the 4 years averaged 75% and ranged from 62% to 88%. The 18-month follow-up averaged 79% and ranged from 67% to 86%.

Institutional Changes

Institutional surveys and institutional assessments were compared from baseline to 18 months. Institutional survey results for the 4-year mean results showed: how effective, how comfortable and how receptive participants believed their settings were in providing survivorship care. Scores started low at 4.51 and 5.79 for effectiveness and comfort of staff with survivorship care. Hence, this was the reasons for participants wanting to attend the course. Scores rose significantly by 18 months to 7.06 and 7.82 (p<0.05). Receptiveness of staff started high at 8.50, but still increased significantly to 8.94 at 18 months. Supportiveness of administration towards improving survivorship care started high at 8.77 but dropped to 8.66 by 18 months (Table 3). Barriers to participating teams documented from baseline to 18 months included a lack of administrative support and financial constraints. Course influence on participants' survivorship activities was rated on a 0 = no influence to 10 = significant influence scale. The 4-year mean influence average was 7.88. When asked if attending the course motivated survivorship care in your setting, 98.1% of the participants said yes.

Table 3. Institutional survey all years baseline to 18 months mean scores.

| Institutional survey years 1–4 | Scale 1–10 | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| BL Score Mean - 18 | Mo. Score Mean | |

| How effective is survivorship care in your setting? | 4.50 | 7.06* |

| How comfortable is your staff with survivorship care? | 5.79 | 7.82* |

| How receptive is your staff to survivorship care?* | 8.50 | 8.94* |

| How supportive is your administration to improving survivorship care? | 8.77 | 8.66 |

P=0.05 (statistically significant change)

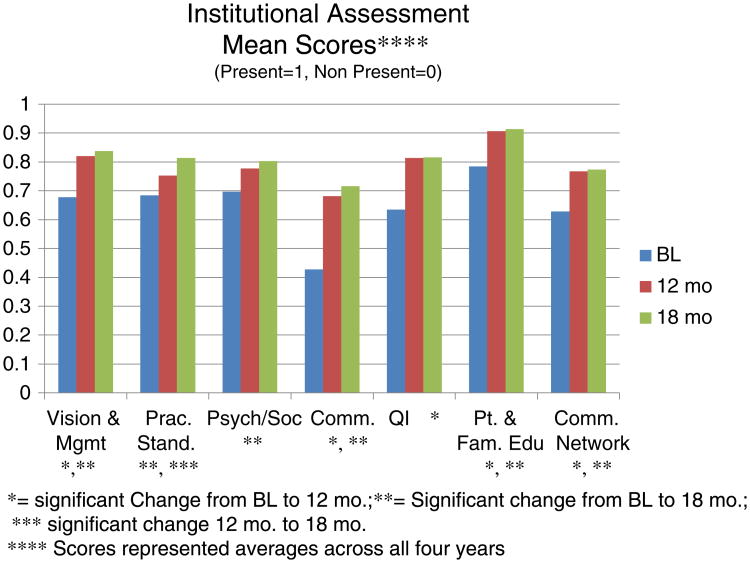

Institutional assessments are presented as mean measures combining all four annual courses. Scores were compared from baseline to 12 months and to 18 months. Percentage of participants providing follow-up averaged for 12 months was 74% and ranged from 60% to 88%, 18-month follow-up averaged 77% and ranged from 67% to 84%. There were significant changes for vision and management standards which showed a change in focus as survivorship goals were implemented into the vision and management statements of the institutions. All domains showed a significant change and improvement between baseline and 18 months with quality improvement changing from baseline to 12 months and maintaining between 12 and 18 months. Changes in the institutional assessment revealed significant changes in the domains of care (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Institutional assessment mean scores (present = 0, nonpresent = 1). Scores represented averages across all 4 years. Asterisk indicates significant change from BL to 12 months; two asterisks indicate change from BL to 18 months; three asterisks indicate significant change 12 months to 18 months

Discussion

Survivorship Education for Quality Cancer Care provided education on survivorship care to 204 teams from across the U.S. Courses were oversubscribed with twice as many applications as positions each year. Faculty was knowledgeable and experienced in survivorship care which was evident by the high evaluation scores received. Health care professionals involved with cancer care recognized the importance of being prepared to meet the needs of this growing cancer survivorship population. Nevertheless, the number of institutions participating compared with the number of cancer institutions in the country illustrates a continued high need for additional educational opportunities.

Minority populations are at the greatest risk for loss to follow-up after cancer treatment due to lack of insurance or lack of communication regarding follow-up care needs. While our participants were mostly female and Caucasian, demographics showed that the populations served were 30% minority. Through education, we can better prepare health care professionals to anticipate the needs of these survivors.

Institutional surveys revealed that supportiveness by administration towards providing survivorship care decreased somewhat by 18 months. Part of the initial application required administrative support letters, and participants found that supportiveness in their institutions decreased when they returned home with lower energy and support than they had anticipated. Barriers were related to financial support and the type of activities the team hoped to achieve. Teams found the need to explore outside community resources, grant support of programs and creative methods in an effort to raise money for their planned activities.

In general, the institutional assessments increased significantly from baseline to 18 months. A few institutions had continued challenges in integrating survivorship care in the institution. A number of settings were building new cancer centers and their resources were consumed by building costs. This limited the participating team's ability to implement new policies and protocols for survivorship care. Psychosocial and emotional standards improved over the time period for all years. This is an important change as the area of psychosocial and emotional care has been shown to be deficient for most cancer survivors. The communication domain improved significantly over the 4 years and may be indicative of the growing focus on treatment summaries and survivorship care plan production and growing development of electronic medical records (EMR).

Changing institutional practice is challenging [7,20]. Competing priorities frequently interfere with the establishment of new programs in survivorship care. If an institution's vision statement included survivorship care as part of their overall vision and mission statements, the setting had a much better chance of being successful and changing care. Building staff support was essential. Without physicians and staff recognizing the necessity of this care within the trajectory of the cancer experience, progress in survivorship care will not occur. Budgets are limited and survivorship care is usually not an income generator by itself.

Promoting health and prevention is a key focus of health education in general and important for the cancer survivor to achieve their highest quality of life and reduce complications and costs of future health care. National health care priorities and evolving standards of health care will have continued influence in establishing cancer survivorship care. The Commission on Cancer (CoC), part of the American College of Surgeons accredits cancer centers [2]. New CoC standards for 2015 will require the use of the survivorship treatment summary and improved navigation for cancer patients posttreatment. These standards will provide an important impetus to many cancer settings seeking this certification to initiate and or provide continued support for cancer survivorship services.

In summary, Survivorship Education for Quality Cancer Care has begun to fill the educational needs of health professionals on survivorship components of care and program models. Education was aimed at settings assessing their own characteristics and identifying deficits in care. This course was successful as illustrated by the excellent rating of curriculum and faculty, significant changes in staff characteristics at participating institutions as well as changes in institutional characteristics that reflect an increased integration of survivorship care.

Additional educational opportunities are needed to prepare oncologists and primary care physicians on the consequences of cancer care in long-term survivors [5,9]. Using advanced practice nurses and physician assistants to assist with this population is an essential component in preparing for this care. Additional courses are currently offered through other institutions such as LiveSTRONG and George Washington University as well as City of Hope. Resources are available through books, journals and online support programs through LiveSTRONG, National Coalition of Cancer Survivors (NCCS) [18], Office of Cancer Survivorship (NCCS; [19]) (“Lance Armstrong Foundation” [13]). Many of the program participants continue to provide education in their individual settings and communities and together are working to improve the care of survivors through integration of services, improved communication and coordination with community resources. Providing education to health care providers is improving survivorship care for the participating teams and continues to impact care today.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NCI-R25CA107109. Authors would like to thank the faculty: Kimlin Ashing-Giwa, PhD; Smita Bhatia, MD; Diane Blum, MSW; Marilyn Bookbinder, RN, PhD; Katherine Brown-Saltzman, RN, MSN; Michael Feuerstein, PhD, MPH; Patricia Ganz, MD; Sheldon Greenfield, MD; Sue Hieney, PhD, FAAN; Melissa Hudson, MD; Linda Jacobs, RN, PhD; Paul Jacobsen, PhD; Diana Jeffery, PhD; Judi Johnson, RN, MPH, PhD, FAAN; Vicki Kennedy, LCSW; Wendy Landier, NP; Susan Leigh, RN, BSN; Mary McCabe, RN, MA; Ruth McCorkle, PhD, FAAN, AOCN; Sandra Millon-Underwood, RN, PhD Shirley Otis-Green, MSW, ACSW, LCSW, OSW-C; Margaret Riley, RN, MN, CNAA; Leslie Robison, PhD; Sheila Santacroce, APRN, PhD; Renee Sevy-Rickles, MSW; and Bradley Zebrack, PhD, MSW, MPH.

Contributor Information

Marcia Grant, Email: mgrant@coh.org, City of Hope, Division of Nursing Research and Education, 1500 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010, USA.

Denice Economou, City of Hope, Division of Nursing Research and Education, 1500 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010, USA.

Betty Ferrell, City of Hope, Division of Nursing Research and Education, 1500 East Duarte Road, Duarte, CA 91010, USA.

Gwen Uman, Vital Research, LLC, 6380 Wilshire Blvd. Suite 1609, Los Angeles, CA 90048, USA.

References

- 1.American Association of Colleges of Nursing (2010, September 20, 2010) Nursing shortage fact sheet. Retrieved November 7, 2011, from http://www.aacn.nche.edu/media-relations/NrsgShortageFS.pdf.

- 2.American College of Surgeons, and Commission on Cancer. Cancer program standards—2012: ensuring patient centered care. 2012 Retrieved November 3, 2011, 2011, from http://www.facs.org/cancer/coc/cocprogramstandards2012.pdf.

- 3.American Hospital Association. Fast facts on U S hospitals. 2010 Retrieved November 7, 2011, 2011, from http://www.aha.org/research/rc/stat-studies/101207fastfacts.pdf.

- 4.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Future supply and demand of oncologists: challenges to assuring access to oncology services. 2011 Retrieved November 7, 2011 from www.asco.org/workforce.

- 5.Aziz NM. Late effects of cancer treatment. In: Ganz PA, editor. Cancer survivorship today and tomorrow. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 54–76. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burkett V, Cleeland CS. Symptom burden in cancer survivorship. [PDF] Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2007;1(2):167–175. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cadmus E. Your role in redesigning healthcare. Nurs Manage. 2011;42(10):32–42. quiz 43. doi: 10.1097/01.NUMA.0000405221.94055.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrell B, Dow KH. Quality of life among long-term cancer survivors. Oncology. 1997;11:565–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant M, Economou D. Building a critical mass of health-care providers, administrators, and services for cancer survivors. In: Feuerstein M, Ganz PA, editors. Health services for cancer survivors. Springer; New York: 2011. pp. 261–274. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant M, Economou D, Ferrell B, Bhatia S. Preparing professional staff to care for cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1(1):98–106. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0008-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant M, Hanson J, Mullan P, Spolum M, Ferrell B. Disseminating end-of-life education to cancer centers: overview of program and of evaluation. J Cancer Educ. 2007;22(3):140–148. doi: 10.1080/08858190701589074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. Institute of Medicine [IOM] From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. The National Academies Press; Washington DC: 2006. pp. 9–186. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lance Armstrong Foundation. Retrieved 2007, from http://www.livestrong.org.

- 14.Lewis FM. The effects of cancer survivorship on families and caregivers. More research is needed on long-term survivors. [PDF] Am J Nurs. 2006a;106(3 Suppl):20–25. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200603003-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mao JJ, Bowman MA, Stricker CT, DeMichele A, Jacobs L, Chan D, Armstrong K. Delivery of survivorship care by primary care physicians: the perspective of breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(6):933–938. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller K, Triano L. Medical issues in cancer survivors—a review. The Cancer Journal. 2008;14(6):375–387. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818ee3dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller KD. Cancer survivors, late and long-term issues. Cancer J. 2008;14(6):358–360. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818f046c00130404-200811000-00003[pii]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.NCCS. National Coalition of Cancer Survivors (NCCS) from www.canceradvocacy.org.

- 19.Office of Cancer Survivorship. Fact sheet. 2006 Retrieved (2006) May 17, 2010, from http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs/

- 20.Periyakoil VS. Change management: the secret sauce of successful program building. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(4):329–330. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.9645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rechis R, Reynolds K, Beckjord EB, Nutt S, Burns RM, Schaefer J. LIVESTRONG; Austin: 2011. “I learned to live with it” is not good enough: challenges reported by post-treatment cancer survivors in the LIVESTRONG surveys. Retrieved from http://livestrong.org/pdfs/3-0/LSSurvivorSurveyReport_final. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowland JH. What are cancer survivors telling us? Cancer J. 2008;14(6):361–368. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e31818ec48e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rowland JH, Stefanek M. Introduction: partnering to embrace the future of cancer survivorship research and care. Cancer. 2008;112(11 Suppl):2523–2528. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Statistical Research and Applications Branch, based on November 2006 SEER data submission. From National Cancer Institute; Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results Program (2007 released) US estimated complete prevalence counts on 1/1/2004. www.seer.cancer.gov. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yancik R. Cancer burden in the aged: an epidemiologic and demographic overview. Cancer. 1997;80(7):1273–1283. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19971001)80:7<1273∷AID-CNCR13>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yancik R, Ganz PA, Varricchio CG, Conley B. Perspectives on comorbidity and cancer in older patients: approaches to expand the knowledge base. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(4):1147–1151. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.4.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]