Abstract

Purpose

Sigma receptors (σR) are non-opioid, non-phencyclidine binding sites with robust neuroprotective properties. σR1 is expressed in brain oligodendrocytes, but its expression and binding capacity have not been analyzed in retinal glial cells. This study examined the expression, subcellular localization, binding activity and regulation of σR1 in retinal Müller cells.

Methods

Primary mouse Müller cells (1°MC) were analyzed by RT-PCR, immunoblotting and immunocytochemistry for the expression of σR1 and data were compared to the rat Müller cell line, rMC-1 and rat ganglion cell line, RGC-5. Confocal microscopy was used to determine the subcellular σR1 location in 1°MC. Membranes prepared from these cells were used for binding assays using [3H]-pentazocine (PTZ). The kinetics of binding, the ability of various σR1 ligands to compete with σR1 binding and the effects of nitric oxide (NO) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) donors on binding were examined.

Results

σR1 is expressed in 1°MC and is localized to the nuclear and endoplasmic reticulum membranes. Binding assays showed that in 1°MCs, rMC-1 and RGC-5 cells, the binding of PTZ was saturable. [3H]-PTZ bound with high affinity in RGC-5 and rMC-1 cells and the binding was similarly robust in 1°MC. Competition studies showed marked inhibition of [3H]-PTZ binding in the presence of σR1-specific ligands. Incubation of cells with NO and ROS donors markedly increased σR1 binding activity.

Conclusions

Müller cells express σR1 and demonstrate robust σR1 binding activity, which is inhibited by σR1 ligands and is stimulated during oxidative stress. The potential of Müller cells to bind σR1 ligands may prove beneficial in retinal degenerative diseases such as diabetic retinopathy.

Keywords: sigma receptor, Müller cells, neuroprotection, ganglion cells, nitric oxide, oxidative stress

Introduction

Sigma receptors (σRs) are nonopiate, nonphencyclidine binding sites [1], whose ligands have robust neuroprotective properties. The endogenous ligand and physiological function of σR1 have not been elucidated. σRs consist of several subtypes distinguishable by biochemical and pharmacological means [2]. Among these, type 1 σR (σR1) is best characterized. The cDNA encoding σR1 was cloned originally from guinea pig liver [3] and subsequently from human, mouse and rat [4-7]. The σR1 cDNA predicts a protein of 223 amino acids (Mr 25-28 kD) [3]. Initial hydropathy analysis of the deduced σR1 amino acid sequence suggested a single transmembrane segment [3,4,6]; recently Aydar and colleagues [8] showed that, when expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes, σR1 has two transmembrane segments with the NH2 and COOH termini on the cytoplasmic side of the membrane.

σR1 distribution has been analyzed in brain and its association with neurons is well established [9]. The receptors modulate ion channel activities at the plasma membrane, neuronal firing and release of certain neurotransmitters. These receptors are of interest because of their profound capacity to prevent neuronal cell death. They inhibit ischemia-induced glutamate release [10,11], attenuate postsynaptic glutamate-evoked Ca2+ influx [12,13], depress neuronal responsivity to NMDA receptor stimulation [14-16], and reduce NO production [17].

In retina, the role of σR1 recognition sites in ischemia-reperfusion injury, in controlling intraocular pressure and in protection against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity has been reported [18 – 20]. Binding assays, using bovine retinal membranes, suggested the presence of σRs [21, 22], but the studies did not disclose in which retinal cell types σRs were present, nor did they establish unequivocally the molecular identity of the receptor. Recently, we used molecular and biochemical methods to study σR in mouse retina and reported widespread expression of σR1 [23]. RT-PCR analysis amplified σR1 in neural retina, RPE-choroid complex and lens. In situ hybridization studies revealed abundant expression of σR1 in the ganglion cell layer, inner nuclear layer, inner segments of photoreceptor cells, and RPE cells. Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed these observations. Subsequent studies focused on ganglion cells, owing to their vulnerability in diabetic retinopathy, and revealed that σR1 continues to be expressed under hyperglycemic conditions and during diabetic retinopathy [24], making it a promising target for neuroprotection against cell death. More recent work using the rat ganglion cell line, RGC-5, showed that (+)-pentazocine, a σR1 specific compound, can block RGC-5 cell death induced by homocysteine and glutamate [25].

Despite evidence that σR1 is present in RGCs and other retinal cell types; there have been no studies of σR1 binding activity in isolated retinal cells. In this study, we examined σR1 binding in retinal Müller cells using the rat cell line (rMC-1) and primary Müller cells (1°MCs) and in RGC-5 cells. The rationale for studying σR1 binding activity in Müller cells is that recent studies have demonstrated a possible role for σR in glial cell maintenance. Pharmacological studies showed that C6 glioma cells have σR binding sites [26]. Immunohistochemical studies demonstrated that, in addition to neurons, σR1 is present also in oligodendrocytes [27] and Schwann cells [28]. Hayashi and Su confirmed σR1 presence in oligodendrocytes and localized it to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) forming galactosylceramide-enriched lipid rafts in the myelin sheet of mature oligodendrocytes [29]. They speculated that σRs are important for oligodendrocyte differentiation and may play a role in the pathogenesis of certain demyelinating diseases.

Müller cells, the key retinal glial cell, span the retinal thickness, contacting and ensheathing neuronal cell bodies and processes. They are crucial role for neuronal survival providing trophic substances and precursors of neurotransmitters to neurons [30]. Most retinal diseases are associated with reactive Müller cell gliosis, which may contribute to neuronal cell death; hence, we sought to characterize σRs in these cells. Our earlier work with the rat Müller cell line, rMC-1, suggested that σR1 mRNA was present in these cells [24]. In this study we confirmed that finding and extended the analysis to Müller cells isolated from mouse retina (primary cell culture). We analyzed the subcellular localization of σR in 1°MCs. Additionally, we used rMC-1, RGC-5 and 1°MCs to analyze the binding characteristics of σR1. Our study represents the first comprehensive analysis of σR1 in Müller cells and the first information about the binding characteristics of this receptor in any isolated retinal cell type.

Methods and Materials

Reagents

Reagents were obtained from the following sources: DMEM:F12, TRIzol, penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco-Invitrogen Corp., Grand Island, NY); fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA); [1,3-3H] (+)-pentazocine (specific radioactivity 37 Ci/mmol), [2,3-3H] -(+)-3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)N-(1-propyl)piperidine [3H]-(+)-3-PPP] (specific radioactivity 92.4 Ci/mmol) (DuPont-NEN, Boston, MA); IgG-HRP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); Cy-3 IgG, Alexa Fluor 488-IgG and 568-IgG (In Vitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); monoclonal anti-Lamin A and monoclonal anti-PDI (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA), polyclonal anti-vimentin (Chemicon Intl., Temecula, CA); ECL detection kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford, IL); Bio-Rad Protein Assay Reagent (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA); Power Block (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA); complete Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail tablets, GeneAmp RNA PCR Kit (Applied Biosystems/Roche Molecular System, Branchburg, NJ); TaKaRa Taq™ (Takara Bio Inc, Otsu, Shiga, Japan); sense and antisense primers for rat and mouse σR1 (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc, Coralville, IA); (+)-3-PPP, carbetapentane, 1,3-di-(2-tolyl)guanidine (DTG), haloperidol, and phenytoin (Research Biochemicals, Natick, MA); (+)-pentazocine, anti-β-actin, 3-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP), S-nitrosoglutathione (SNOG), 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1), hydrogen peroxide 30% (W/W) solution, xanthine, xanthine oxidase (X/XO) and all other chemicals (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO); rMC-1 cells and RGC-5 cells were kind gifts, respectively, of Dr. V. P. Sarthy and Dr. N. Agarwal. Anti-CRALBP was a generous gift from Dr. J. Saari.

Animals and isolation of Müller cells

C57Bl/6 mouse breeding pairs, purchased from Harlan Sprague-Dawley, (Indianapolis, IN), were maintained in our colony following the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Müller cells were isolated from 6-7 day mice following our published methods [31], which were adapted from those of Hicks and Courtois [32]. Briefly, eyeballs are removed, placed in DMEM with gentamicin and soaked 3 h at 25°C in the dark. They are rinsed in PBS, incubated in buffer containing trypsin, EDTA and collagenase. Retinas are removed from eyeballs (taking care to avoid contamination by pigmented RPE), and placed in DMEM supplemented with glucose, FBS, penicillin/streptomycin and gently pipetted into small aggregates at a density of 10-16 retinas/dish. Isolated cells are detectable within 1-3 days. By 3-5 days substantial cell growth ensues. Cultures are washed vigorously with medium until only a strongly adherent flat cell population remains. Cells are passaged 1-3 days after washing, seeded into culture flasks (50,000 cells/cm2); culture media is changed three times per week. The purity of the cultures is verified using antibodies that are known markers of Müller cells (CRALBP, vimentin, glutamine synthetase, GLAST). It is noteworthy that GFAP, typically considered a marker of Müller cells under stress, is detected only at a low level [31]. Immunocytochemical studies using markers for neurons (neurofilament-L, a major component of neuronal cytoskeleton) and RPE (RPE-65) show minimal detection.

Cell Culture

Primary mouse Müller cells (1°MC), rMC-1 and RGC-5 cells [31, 33, 34] were cultured in DMEM:F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and were maintained at 37°C in a humidified chamber of 5% CO2. Medium was replaced every other day. Upon confluence, cultures were passaged by dissociation in 0.05% (w/v) trypsin in PBS.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of σR1 mRNA

Total RNA was prepared from confluent 1°MC, rMC-1and RGC-5 cells using TRIzol. For the two cells lines (rMC-1 and RGC-5), which were derived from rat [33,34], RT-PCR was carried out using primer pairs specific for rat σR1 [7]: 5′-GTT TCT GAC TAT TGT GGC GGT GCT G -3′ (sense) and 5′-CAA ATG CCA GGG TAG ACG GAA TAA C -3′ (antisense) (nucleotide position 80-104 and 567-591; expected PCR product size: 512 bp). For the 1°MCs, isolated from mouse, RT-PCR was carried out using primer pairs specific for mouse [6]: 5′- CTC GCT GTC TGA GTA CGT G -3′ (sense) and 5′-AAG AAA GTG TCG GCT GCT AGT GCA A - 3′ (antisense) (nucleotide position 315-333 and 572-593; expected PCR product size: 279 bp). 18S RNA was the internal standard. RT-PCR was done at 35 cycles, with a denaturing phase of 1 min at 94°C, annealing phase of 1 min at 59°C, and an extension of 2 min at 72°C. 20 μl of the PCR products were gel electrophoresed and stained with ethidium bromide.

Immunoblot analysis of σR1

Immunodetection of σR1 in RGC-5, rMC-1, and 1°MCs followed our published methods [24, 35]. Protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were blocked 1.5 h with Tris-buffered-saline-0.05% Tween-20 containing 5% non-fat milk. Membranes were incubated with anti-σR1 antibody (1:1000) [24] overnight at 4°C followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (1:5000). After washing, proteins were visualized using the ECL western blot detection system. Membranes were washed thrice, blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 2 h and were reprobed with mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (1:5000) as a loading control.

Immunocytochemical analysis of σR1

σR1 detection in RGC-5, rMC-1 and 1°MCs cells followed our published protocol [23-25, 35]. Cells were incubated with polyclonal anti-σR1 antibody (1:100) [24] and subsequently with Cy-3-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:200). Negative control experiments were performed by incubating the slides without the primary antibody. σR1 was detected by epifluorescence using a Zeiss Axioplan-2 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Göttingen, Germany) and the axiovision program. For σR1 subcellular localization studies, 1°MCs, cells were seeded on coverslips, grown for 24 h, fixed in ice-cold methanol 10 min, air dried, washed in PBS, blocked with Power Block and were incubated overnight at 4°C with the σR1 antibody (1:100) [24] and either the monoclonal anti-Lamin A (nuclear membrane marker, 1:25) or the monoclonal anti-PDI (ER marker, 1:25). Cells were then incubated 30 min with goat anti-rabbit IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 568 and goat anti-mouse IgG coupled to Alexa Fluor 488 (1:1500). Negative control sections were treated identically except that PBS replaced the primary antibodies. Coverslips containing the cells were mounted with Vectashield Hardset mounting media on microscope slides and examined with a Zeiss confocal microscope using LSM 510 Meta imaging software.

Preparation of cell membranes for binding assays

RGC-5, rMC-1 and 1°MCs were cultured as described above. Cell monolayers were chilled on ice, washed with ice-cold PBS (pH 7.5), lysed using 5 mM K2HPO4-KH2PO4 buffer (pH 7.5). The suspension was centrifuged 30 min at 25,000 rpm; the final membrane pellets were rinsed and suspended in 5 mM K2HPO4-KH2PO4 buffer and rehomogenized 20 times using a 25g needle. The protein concentration in the final membrane preparation was measured using the Bio-Rad protein assay.

Ligand binding assay

[3H]-(+)-pentazocine binding to membrane preparations was assayed as described with minor modifications [36]. Samples were incubated with [3H]-(+)-pentazocine (10 nM) in 250 μl 5 mM K2HPO4-K2PO4 buffer, pH 7.5, 25°C, 90 min. Binding was terminated by adding ice-cold binding buffer and the mixture was filtered on a Whatman GF/F glass fiber filter, presoaked in 0.3% polyethyleneimine. The filter was washed thrice with ice-cold binding buffer and radioactivity associated with the filter was determined by liquid scintillation spectrometry. To study the inhibition of [3H]-pentazocine binding to the σR1, several competitive inhibitors (+)-3-PPP, carbetapentane, DTG, haloperidol, and (+)-pentazocine were used. The concentrations for the [3H]-pentazocine and the inhibitors were 50 nM and 1 μM, respectively. To investigate the allosteric effects of phenytoin on σR1, 150 μl of rMC-1 membrane preparation containing 300 μg of protein was incubated with 50 μl of 125 nM of [3H](+)-3-PPP (final concentration 25 nM) and 50 μl of 250 μM phenytoin (final concentration 50 μM) or its solvent (5 mM K2HPO4 buffer containing 2.5% DMSO, pH 7.5) for 90 min at 25°C. The final volume of the reaction system was 250 μl. 50 μM unlabeled (+)-pentazocine was used to define non-specific binding.

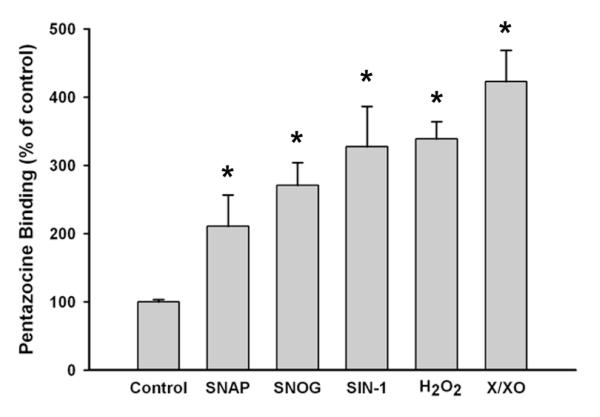

The effects of donors of nitric oxide (NO) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) on σR1 binding activity were examined by treating rMC-1 cells on the 2nd day following seeding for 6 h with the NO donors SNAP (250 μM), SNOG (250 μM) and SIN-1 (100 μM) or the ROS donors H2O2 (0.00025%) and xanthine (25 μM)/xanthine oxidase (10 mU/ml), after which the binding activity was assayed as described above.

Data analysis

Experiments were performed in duplicate or triplicate; each experiment was repeated at least two times. Results are expressed as mean ± SE. The equilibrium saturation binding parameters, dissociation constant (Kd), and the maximum number of binding sites (Bmax) were calculated by nonlinear regression analysis of the equation for a rectangular hyperbola using SigmaPlot 2001 for Windows version 7.0. Statistical significance (p <0.05) was determined using SigmaStat, Version 2.

Results

Analysis of σR1 expression in Müller and ganglion cells

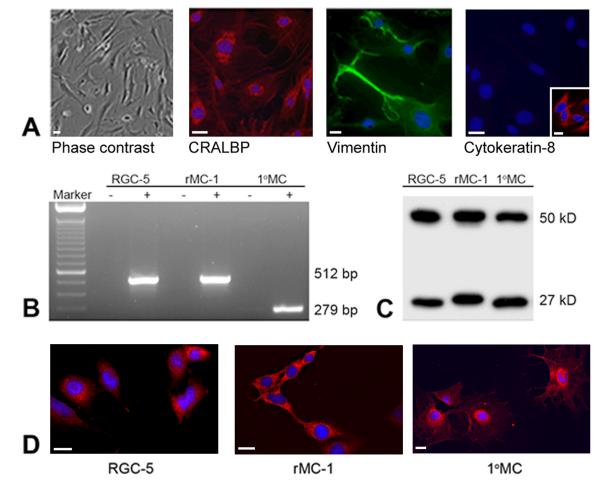

The purity of the mouse Müller cells [31] was confirmed using known antibody markers for Müller cells, including CRALBP and vimentin (Fig.1 A) and glutamine synthetase (data not shown). The cells were not positive for neuronal markers such as NF-L [31] nor were they positive for cytokeratin-8, which labels RPE cells (Fig. 1A). For expression and ligand-binding studies, 1°MCs were used at passage number 5. RT-PCR of the mouse 1°MCs amplified the expected PCR product (279 bp) (Fig. 1B), indicating that σR1 is expressed in these cells. The RT-PCR analysis of the rat cell lines amplified the expected product (512 bp) consistent with our earlier data using these cell lines [23]. Immunoblotting with an antibody specific for σR1 [24] detected a protein band of the expected size (Mr ~27kD) in 1°MCs, rMC-1 and RGC-5 cells. Immunocytochemical analysis of the cells detected σR1 in RGC-5, rMC-1, and 1°MCs (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1. Analysis of σR1expression in retinal cell lines and in primary mouse Müller cells (1°MCs).

(A) Verification of the purity of the 1°MCs used in these studies. The left panel shows a phase contrast image of cells grown for 3 days in culture and the middle two panels show positive immunostaining for CRALBP (red fluorescence) and vimentin (green fluorescence). The right panel shows immunolabeling with cytokeratin-8, which is negative in the Müller cells, but is positive in ARPE-19 cells (red fluorescence, inset). (B) RT-PCR showing expression of σR1 mRNA in rat ganglion (RGC-5) and Müller (rMC-1) cell lines (512 bp) and mouse 1°MCs (279 bp). For each cell type, PCR was run in the absence (−) or presence (+) of reverse transcriptase. (C) Immunoblotting of RGC-5, rMC-1 and 1° MC showing detection of σR1 (Mr ~27 kD) and β-actin (Mr ~50 kD). (D) Cell lines or 1°MCs were cultured as described in the text and subjected to immunocytochemistry to detect σR1 followed by a Cy-3 conjugated secondary antibody (red staining); DAPI was used to label nuclei (blue). σR1 was detected in the cell lines (RGC-5, rMC-1) and in 1° MCs. Calibration bar = 15 μm.

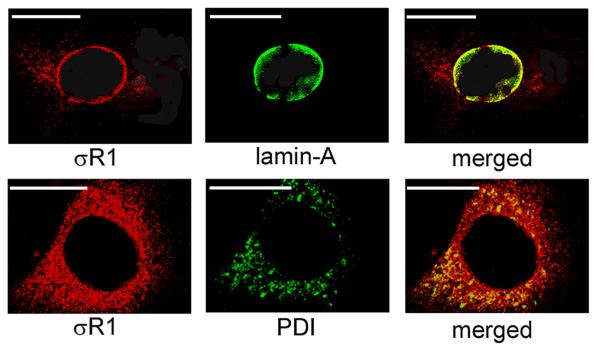

To analyze the subcellular location of σR1 in 1°MCs markers for the nuclear and ER membranes were used in double-labeling experiments with the σR1 antibody. As shown in Fig. 2A, σR1 was present in the area consistent with the nuclear membrane and the merged image of the σR1 plus the nuclear membrane marker, lamin-A, showed marked co-localization suggesting that σR1 is present on the nuclear membrane. Similarly, optical sectioning at a slightly different plane of the cells showed intense σR1 levels in the perinuclear area, consistent with ER localization. The merged image of the σR1 and the ER membrane protein, PDI (Fig. 2) provides strong evidence that σR1 is present also in the ER.

Fig. 2. Subcellular localization of σR1 in1°MCs.

Müller cells were isolated from mouse retina and cultured as described in the text. They were subjected to double-labeling immunocytochemical analysis using a polyclonal antibody specific for σR1 (red fluorescence) and monoclonal antibodies (green fluorescence) that label the nuclear membrane (lamin-A) or the endoplasmic reticulum (PDI). Optical sectioning by confocal microscopy detected co-localization of σR1 with lamin-A (merged image) and with PDI (merged image). In the merged images, the orange signal is detected when the red and green fluorescence overlap indicative of colocalization. Calibration bar = 15 μm.

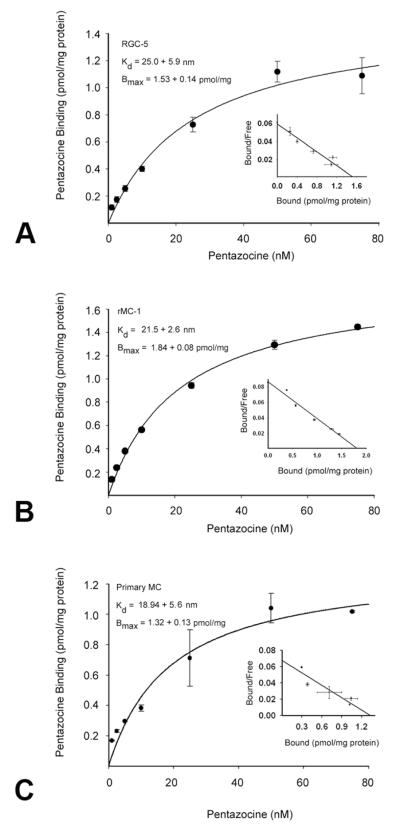

Characterization of [3H](+)-pentazocine binding in retinal cell membranes

σR1 binding in RGC-5, rMC-1 and 1°MC cells was characterized using (+)-pentazocine, a high-affinity σR1 ligand [37]. The binding was saturable over a (+)-pentazocine concentration range of 1.25-75 nM (Fig. 3). The apparent dissociation constants (Kd) were 25.0 ± 5.9 nM, 21.5 ± 2.6 and 18.9 ± 5.6 nM for RGC-5, rMC-1 and 1°MCs, respectively. Thus, in the cell lines derived from rat and in 1°MCs obtained from mouse, the affinity constant for the protein is comparable to the cloned σR1 from rat and mouse. Scatchard analysis of the binding data revealed the presence of a single binding site in each cell type. The binding constants (Bmax) calculated for the RGC-5, rMC-1 and 1°MCs were 1.53 ± 0.14, 1.84 ± 0.08 and 1.32 ± 0.13 pmol/mg protein, respectively. These data suggest that the receptor density is comparable between the retinal cell lines and the 1°MCs.

Fig. 3. Saturation kinetics of σR1 binding in membrane preparations.

The two retinal cell lines (RGC-5 and rMC-1) and 1°MCs were cultured as described, membranes prepared and the binding of [3H](+)-pentazocine over a broad concentration range measured in (A) RGC-5 cells; (B) rMC-1 cells, and (C) 1°MCs. Values are the mean ± SE for two independent experiments performed in triplicate. Inset, Scatchard plot.

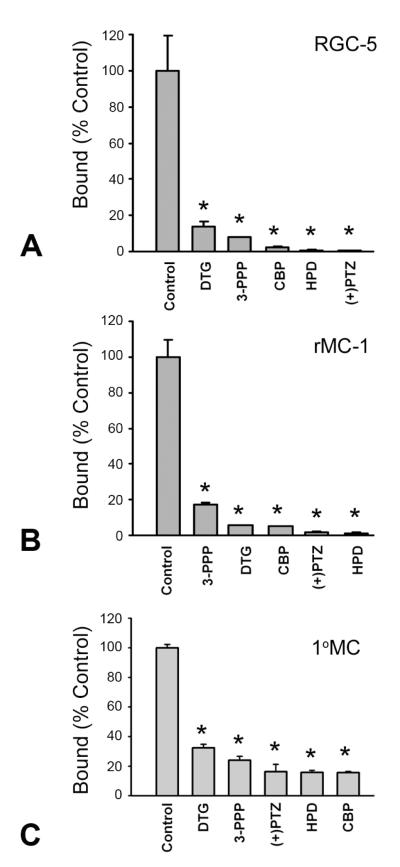

The binding of [3H](+)-pentazocine (final concentration 25 nM) to RGC-5, rMC-1 and 1°MC membranes was inhibited by several σR1 ligands (Fig. 4). The order of potency differed somewhat between the cell type being studied, such that in RGC-5 cells it was (+)-pentazocine > haloperidol > carbetapentane > 3-PPP > DTG and in rMC-1 cells it was: haloperidol > (+)-pentazocine > carbetapentane = DTG > 3-PPP. In the 1°MCs the order of potency was carbetapentane = haloperidol > (+)-pentazocine > 3-PPP > DTG.

Fig. 4. Inhibition of [3H](+)-pentazocine binding by σR1 ligands.

RGC-5, rMC-1 and 1°MCs were cultured as described, membranes prepared and the inhibition of the binding of [3H](+)-pentazocine was measured using several known ligands for σR1. (A) RGC-5 cells; (B) rMC-1 cells, and (C) 1°MCs. Data are shown as relative percent of control binding (100%) measured in the absence of ligands. Values are the mean ± SE for two independent experiments performed in triplicate. 3-PPP: (+)-3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)-N-(1-propyl)piperidine; CBP: carbetapentane; DTG: 1,3-di-(2-tolyl)guanidine; HPD: haloperidol; (+)-PTZ: (+)-pentazocine. (*Significantly different from control, p <0.01).

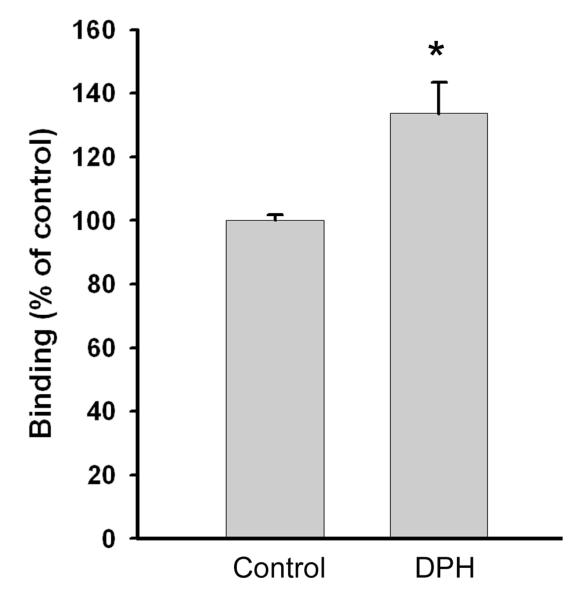

A key pharmacological characteristic of type 1 sigma receptors, which distinguishes them from the type 2 receptors, is the allosteric enhancement of binding of ligands to the σR1 in the presence of phenytoin [9]. Stimulation of binding of the σR1 agonist (+)-3-PPP in the presence of phenytoin was reported recently in guinea pig brain [38]. We used the 1°MCs to confirm that the σR binding we were studying was specific to type 1 (σR1). In these studies the binding of [3H](+)-3-PPP was examined in the absence and presence of 50 μM phenytoin. There was a 35% stimulation of binding activity in the presence of phenytoin (Fig. 5). The data suggest that the binding activity measured in the isolated Müller cells is specific to σR1.

Fig. 5. Allosteric effects of phenytoin on the binding of [3H]-3-PPP.

The rMC-1 cell line was cultured and membranes prepared as described. The allosteric effect on [3H]-3-PPP binding activity in the absence (Control) or presence of phenytoin (DPH) was measured after a 90 min incubation as described. Values are mean ± SE for two experiments performed in triplicate. (*Significantly different from control, p <0.01).

The ability to analyze σR1 binding activity in individual retinal cell types affords the opportunity to investigate the regulation of this activity in the presence of factors implicated in retinal disease. While it was not the focus of this paper to investigate exhaustively the regulation of σR1, it is important to ascertain whether binding activity is likely to be altered when retinal cells are subjected to stress. To this end we performed preliminary studies in rMC-1 cells and analyzed σR1 binding activity when cells were exposed to either NO or ROS donors. These stressors were selected because, in diabetic retinopathy, NO [39-42] and oxidative stress [43] have been implicated in the pathogenesis of the disease. The cells were exposed to NO donors: SNAP, SNOG, SIN-1 or to ROS donors: H2O2, X/XO for 6 h following which the binding activity of σR1 was assayed. Treatment of rMC-1 cells with all three NO donors resulted in marked increase in binding activity, with the greatest effect observed when cells were incubated with SIN-1. There was an approximate 3-fold increase in binding activity after 6 h exposure to this NO donor. In the experiments using ROS donors, the effects were similarly profound with a 3-fold increase in binding activity following 6 h exposure to H2O2 and nearly 4-fold increase in the presence of X/XO. The findings were observed in three independent experiments.

Discussion

In this study, we examined σR1 expression in isolated retinal cell types and characterized comprehensively σR1 binding activity in these cells. We used molecular techniques and demonstrated that σR1 is present in 1°MCs isolated from the mouse retina. The location of the σR1 appeared to be perinuclear. We explored this question using LSCM analysis with antibodies that recognize the nuclear and ER membranes. Our studies demonstrated that in 1°MCs, σR1 is localized to the both sites. σR1 to the ER was consistent with the studies by Hyashi and Su [29] who localized σR1 to the ER of oligodendrocytes. They did not report localization to the nuclear membrane; however they did not use antibody markers to explore this question, so it is not known whether oligodendrocytes might also place σR1 on the nuclear membrane.

Previous studies of σR in retina have demonstrated σR1 binding activity; however these studies used whole retina from large models (bovine) [21, 22] and did not attempt to study the σR1 binding activities of individual retinal cell types. If we are to postulate a role for σRs in mediating neuroprotection in retinal cells, it is essential to be able to quantify the σR1 binding activity in the isolated cells. We were interested in σR1 binding activity in both ganglion cells and in Müller cells. Ganglion cells die in several retinal diseases [44-46], and we predict that activation of the σR1 may be beneficial to their survival; Muller cells play a key role in neuronal survival [30] and may activate σR1 during stressful episodes providing protection for adjacent neurons. In the present studies, we exploited the retinal ganglion cell line, RGC-5 to study σR1 binding activity in neurons. While isolation of ganglion cells from mouse retina is possible [35], these cells are terminally differentiated making it difficult to obtain sufficient numbers of these neurons to carry out σR1 binding assays. For studies of σR1 in Müller cells, we used the rMC-1 cell line and complemented the data using 1°MCs isolated from mouse. Given the plethora of genetic defects that cause retinal abnormalities in commercially available strains of mice, the ability to study σR1 expression and activity in 1°MC cultures affords an excellent opportunity to dissect σR1 activity and expression in Müller cells of various mouse models of retinal disease.

Our studies of σR1binding characteristics in Müller cells showed that the affinity of σR1 in 1°MCs is comparable to the two retinal cell lines, RGC-5 and rMC-1. In all three cases, σR1 bound its ligand, (+)-pentazocine, with great affinity. The density of receptors as indicated by the Bmax value is similar between the 1°MCs and the two retinal cell lines. The ability of various ligands to inhibit the binding of (+)-pentazocine differed slightly among the cell types. The two cell lines seemed more sensitive to the inhibitory effects of CBP, HPD and (+)-pentazocine, while the 1°MCs seemed slightly less sensitive to these inhibitors. Nonetheless, the binding in these 1°MCs was inhibited by 75-80% over a wide range of ligands tested. Finally, the known allosteric effects of phenytoin to stimulate binding of 3-PPP were borne out in these studies and provide strong evidence that the binding being studied in these retinal cells is indeed mediated by the type 1 sigma receptor.

The value of the present work is that it forms a scaffold upon which to study the regulation of σR1 activity in isolated retinal cells. We now have substantial baseline data for two retinal cell lines and 1°MCs about the dissociation constant, receptor density and ligand specificity characteristics of these receptors. Thus, we are poised to compare these benchmarks under conditions that are known to represent disease states in the retina. For example, in diabetic retinopathy, a variety of factors such as hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, increased levels of NO, and inflammation are thought to figure prominently in the eventual compromised functions of several retina cell types [44]. It will now be possible to evaluate the effects of these factors on the σR1 binding characteristics in isolated retinal cells. While not exploring this comprehensively in the present study, we performed preliminary experiments using NO donors and ROS donors to determine the effects on σR1 binding. Our studies showed that oxidative stress led to increased σR1 binding activity. Future studies will investigate this phenomenon comprehensively, determining whether gene and protein expression are altered under conditions of oxidative stress and characterizing the kinetic parameters associated with this increased activity. In addition to characterizing the binding activity under conditions of oxidative stress, we will use the subcellular localization information obtained in this study for future experiments designed to determine whether oxidative stress induces σR1 to translocate from its typical location at the nuclear and ER membranes to other cellular sites, such as the plasma membrane.

Fig. 6. Regulation of σR1 binding activity by NO and ROS donors.

The rMC-1 cells were cultured as described and were treated for 6 h with nitric oxide (NO) donors: 3-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP, 250 μM), S-nitrosoglutathione (SNOG, 250 μM), or 3-morpholinosydnonimine (SIN-1, 100 μM) or with reactive species (ROS) donors: hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 0.00025%, W/W) solution or xanthine/xanthine oxidase (X/XO, 25 μM/10 mU/ml) following which the binding activity of σR1 was assayed. Values are mean ± SE for two experiments performed in triplicate. (*Significantly different from control, p <0.01).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. V. Sarthy, Northwestern University and Dr. N. Agarwal, University of North Texas Health Science Center for rMC-1 and RGC-5 cell lines, respectively. We thank Dr. J. Saari for the antibody against CRALBP. We acknowledge the assistance of T. Van Ells, L. Amarnath and A. Martin-Studdard in the use of the Zeiss Axioplan 2 microscope.

Supported by: NIH R01 EY014560

Literature Cited

- 1.Monnet FP, Maurice T. The sigma-1 protein as a target for the non-genomic effects of neuro(active)sterioids: molecular, physiological and behavioral aspects. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2006;100:93–118. doi: 10.1254/jphs.cr0050032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quirion R, Bowen WD, Itzhak Y, Junien JL, Musacchio JM, Rothman RB, Su T-P, Tam SW, Taylor DP. A proposal for the classification of sigma binding sites. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1992;13:85–86. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(92)90030-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanner M, Moebius FF, Flandorfer A, Knaus HG, Striessnig J, Kempner E, Glossmann H. Purification, molecular cloning, and expression of the mammalian sigma 1-binding site. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:8072–8077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.8072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kekuda R, Prasad PD, Fei YJ, Leibach FH, Ganapathy V. Cloning and functional expression of the human type 1 sigma receptor (hSigmaR1) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;229:553–558. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prasad PD, Li HW, Fei YJ, Ganapathy ME, Fujita T, Plumley LH, Yang-Feng TL, Leibach FH, Ganapathy V. Exon-intron structure, analysis of promoter region, and chromosomal localization of the human type 1 sigma receptor gene. J. Neurochem. 1998;70:443–451. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70020443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seth P, Leibach FH, Ganapathy V. Cloning and structural analysis of the cDNA and the gene encoding the murine Type 1 sigma receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1997;241:535–540. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seth P, Fei Y-J, Li HW, Huang W, Leibach FH, Ganapathy V. Cloning and functional characterization σ from rat brain. J. Neurochem. 1998;70:922–931. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70030922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aydar E, Palmer C, Klachko V, Jackson M. Sigma receptor as a ligand-modulated auxiliary potassium channel subunit. Neuron. 2002;34:399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maurice T, Urani A, Phan VL, Romieu P. The interaction between neuroactive steroids and the sigma1 receptor function: behavioral consequences and therapeutic opportunities. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2001;37:116–132. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lobner D, Lipton P. σ-Ligands and non-competitive NMDA antagonists inhibit glutamate release during cerebral ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 1990;117:169–174. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90139-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lockhart BP, Soulard P, Benicourt C, Privat A, Junien J-L. Distinct neuroprotective profiles for σ-ligands against N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), and hypoxia-mediated neurotoxicity in neuronal culture toxicity studies. Brain Res. 1995;675:110–120. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)00049-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeCoster MA, Klette KL, Knight KS, Tortella SC. σ Receptor-mediated neuroprotection against glutamate toxicity in primary rat neuronal cultures. Brain Res. 1995;671:45–53. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)01294-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klette KL, DeCoster MA, Moreton JE, Tortella FC. Role of calcium in sigma-mediated neuroprotection in rat primary cortical cultures. Brain Res. 1995;704:31–41. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01103-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhardwaj A, Sawada M, London ED, Koehler RC, Traystman RJ, Kirsch JR. Potent σ1-receptor ligand 4-phenyl-1-(4-phenylbutyl)-piperidine modulates basal and N-methyl-D-aspartate–evoked nitric oxide production in vivo. Stroke. 1998;29:2404–2411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carter C, Benavides J, Legendre P, Vincent JD, Noel F, Thuret F, Lloyd KG, Arbilla S, Zivkovic B, MacKenzie Ifenprodil and SL 82.0715 as cerebral anti-ischemic agents, II: evidence for N-methyl-D-aspartate σ-receptor antagonist properties. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1988;247:1222–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto H, Yamamoto T, Sagi N, Klenerova V, Goji K, Kawai N, Baba A, Takamori E, Moroji T. Sigma ligands indirectly modulate the NMDA receptor-ion channel complex on intact neuronal cells via sigma 1 site. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:731–736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-01-00731.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goyagi T, Goto S, Bhardwaj A, Dawson VL, Hurn PD, Kirsch JR. Neuroprotective effect of sigma(1)-receptor ligand 4-phenyl-1-(4-phenylbutyl) piperidine (PPBP) is linked to reduced neuronal nitric oxide production. Stroke. 2001;32:1613–1620. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.7.1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bucolo C, Drago F. Effects of neurosteroids on ischemia-reperfusion injury in the rat retina: role of sigma1 recognition sites. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004;498:111–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.06.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campana G, Bucolo C, Murari G, Spampinato S. Ocular hypotensive action of topical flunarizine in the rabbit: role of sigma 1 recognition sites. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;303:1086–1094. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.040584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bucolo C, Campana G, Di Toro R, Cacciaguerra S, Spampinato S. Sigma1 recognition sites in rabbit iris-ciliary body: topical sigma1-site agonists lower intraocular pressure. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:1362–1369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Senda T, Mita S, Kaneda K, Kikuchi M, Akaike A. Effect of SA4503, a novel sigma1 receptor agonist, against glutamate neurotoxicity in cultured rat retinal neurons. Eur J Pharmacol. 1998;342:105–111. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Senda T, Matsuno K, Mita S. The presence of sigma receptor subtypes in bovine retinal membranes. Exp Eye Res. 1997;64:857–860. doi: 10.1006/exer.1996.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ola MS, Moore PM, El-Sherbeny A, Roon R, Agarwal N, Sarthy VP, Casellas P, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Expression pattern of sigma receptor 1 mRNA and protein in mammalian retina. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2001;95:86–95. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00249-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ola MS, Martin PM, Maddox D, El-Sherbeny A, Huang W, Roon P, Agarwal N, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Analysis of Sigma Receptor (σR1) expression in retinal ganglion cells cultured under hyperglycemic conditions and in diabetic mice. Brain Res. Mol Brain Res. 2002;107:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00444-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin PM, Ola MS, Agarwal N, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. The Sigma Receptor (σR) Ligand (+)-pentazocine prevents retinal ganglion cell death induced in vitro by homocysteine and glutamate. Brain Research Mol Brain Res. 2004;123:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Georg A, Friedl A. Characterization of specific binding sites for [3H]-1,3-di-o-tolyl-guanidine (DTG) in the rat glioma cell line C6-BU-1. Glia. 1992;6:258–263. doi: 10.1002/glia.440060403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palacios G, Muro A, Vela JM, Molina-Holgado E, Guitart X, Ovalle S, Zamanillo D. Immunohistochemical localization of the sigma1-receptor in oligodendrocytes in the rat central nervous system. Brain Res. 2003;961:92–99. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03892-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palacios G, Muro A, Verdu E, Pumarola M, Vela JM. Immunohistochemical localization of the sigma1 receptor in Schwann cells of rat sciatic nerve. Brain Res. 2004;1007:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayashi T, Su TP. Sigma-1 receptors at galactosylceramide-enriched lipid microdomains regulate oligodendrocyte differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14949–14954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402890101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bringmann A, Reichenbach A. Role of Müller cells in retinal degenerations. Front. Biosci. 2001;6:77–92. doi: 10.2741/bringman. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Umapathy NS, Li W, Mysona BA, Smith SB, Ganapathy V. Expression and function of glutamine transporters SN1 (SNAT3) and SN2 (SNAT5) in retinal Müller cells. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2005;46:3980–3987. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hicks D, Courtois Y. The growth and behavior of rat retinal Müller cells in vitro. 1. An improved method for isolation and culture. Exp Eye Res. 1990;51:119–129. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(90)90063-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarthy VP, Brodjian SJ, Dutt K, Kennedy BN, French RP, Crabb JW. Establishment and characterization of a retinal Müller cell line. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 1998;39:212–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krishnamoorthy RR, Agarwal P, Prasanna G, Vopat K, Lambert W, Sheedlo HJ, Pang IH, Shade D, Wordinger RJ, Yorio T, Clark AF, Agarwal N. Characterization of a transformed rat retinal ganglion cell line. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2001;86:1–12. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00224-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dun Y, Mysona B, Van Ells TK, Amarnath L, Ola MS, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Expression of the glutamate-cysteine (xc−) exchanger in cultured retinal ganglion cells and regulation by nitric oxide and oxidative stress. Cell Tiss. Res. 2006;324:189–202. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-0116-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ramamoorthy JD, Ramamoorthy S, Mahesh VB, Leibach FH, Ganapathy V. Cocaine-sensitive sigma-receptor and its interaction with steroid hormones in the human placental syncytiotrophoblast and in choriocarcinoma cells. Endocrinology. 1995;136:924–932. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.3.7867601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Su TP. Evidence for sigma opioid receptor: binding of [3H]SKF-10047 to etorphine-inaccessible sites in guinea-pig brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1982;223:284–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cobos EJ, Baeyens JM, Del Pozo E. Phenytoin differentially modulates the affinity of agonist and antagonist ligands for sigma 1 receptors of guinea pig brain. Synapse. 2005;55:192–195. doi: 10.1002/syn.20103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldstein IM, Ostwald P, Roth S. Nitric oxide: a review of its role in retinal function and disease. Vision Res. 1996;36:2979–2994. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(96)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmetterer L, Findl O, Fasching P, Ferber W, Strenn K, Breitendeder H, Adam H, Eichler HG, Wolzt M. Nitric oxide and ocular blood flow in patients with IDDM. Diabetes. 1997;46:653–658. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du Y, Sarthy VP, Kern TS. Interaction between NO and COX pathways in retinal cells exposed to elevated glucose and retina of diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R735–741. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00080.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yilmaz G, Esser P, Kociek N, Aydin P, Heimann K. Elevated vitreous nitric oxide levels in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130:87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00398-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frank RN. Diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:48–58. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Levin LA, Gordon LK. Retinal ganglion cell disorders: types and treatments. Prog Retina Eye Res. 2002;21:465–484. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(02)00012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin PM, Roon P, Van Ells TK, Ganapathy V, Smith SB. Death of retinal neurons in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45:3330–3336. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barber AJ, Antonetti DA, Kern TS, Reiter CE, Soans RS, Krady JK, Levison SW, Gardner TW, Bronson SK. The Ins2Akita mouse as a model of early retinal complications in diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:2210–2218. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]