Abstract

Epidemics have been important in human history. This article discusses epidemics as part of a metabolic dialectics of humanity within nature. The creative thoughts and actions of those people most threatened by HIV/AIDS, and the thoughts and actions of science, have shaped both each other and the virus. The virus has reacted through mutation in ways that mimic strategic intelligence. The dialectics of capital and states has shaped these interactions and, in some cases, been shaped by them. Practical action to minimize the harms epidemics do can be strengthened by understanding of these epidemics, and Marxist theory and practices can be strengthened by understanding the dialectics of public health and the struggles around it more fully.

Keywords: Dialectics, Epidemics, Infectious diseases, Nature, Social, HIV, AIDS

Introduction

Epidemics are not just medical phenomena. They often result from sociohistorical situations and unfold as social and historical events and, sometimes, struggle.1 At their most dialectical, as in the case of HIV/AIDS, epidemics encompass interacting dialectics that embrace social, medical, and viral/immunological conflicts over time.

Socially caused epidemics have shaped human history. For example, Columbus and other Europeans brought a wave of diseases against which the populations of the Americas had no immunity. The resulting epidemics devastated indigenous populations and, in many cases, social and cultural orders, making the Americas a relatively easy conquest. Efforts by indigenous groups and some Europeans to ameliorate or stop these epidemics did occur, but little is known about them.2

The social causation of epidemics is not simply a question of transporting bacteria or viruses during trade or migration. Sometimes, it takes the form of human action causing disease vectors such as fleas and rats to move to new environments, as was the case with the Black Death in the Middle Ages, or more recently with mosquitoes and malaria.3

There is some evidence that sociohistorical events can change the form of viruses and other pathogens and cause epidemics in this way. This has been most cogently argued by Paul Ewald.4 Thus, Ewald has argued that the combination of the crowded trench warfare of the First World War interacted with the particular patterns of transportation of sick soldiers to be cared for on the French front to cause an ordinary influenza virus to mutate into a strain of extraordinary virulence that devastated millions of lives. We would add that the social disruption that this epidemic caused may conceivably have influenced the dynamics, and possibly even the outcomes, of the post-war revolutionary upsurge.

We argue here that epidemics are not merely sociohistorical but also dialectical. We exemplify this through discussing HIV/AIDS epidemic.

What is dialectics?

Before going on to analyze epidemics as dialectical processes, we want to present a very brief outline of how we see those aspects of dialectics that we use in this paper. Dialectics is, of course, a much larger topic, which we cannot take up here in depth. Our work on dialectics has been heavily shaped by the work of Hegel, Marx, and Engels and by more recent authors including (in alphabetical order) Anderson, Dunayevskaya, James, Lenin, Levins, Lewontin, Lukacs, Marcuse, and Ollman.5

Dialectics is a method of thought and of speculation. (Some would also argue that reality itself is dialectical—we discuss this later in the paper). It is a method that differs radically from the usual “reductionist” ways of thought in science, which view reality “analytically” as built up from discrete units that cause changes in each other and that may coalesce to form larger wholes. It also disagrees with Aristotelian logic that starts from the assumption that things are either “A” or “not A” but not both. Dialectics also differs from non-dialectical forms of epidemiology (the science of epidemics) that view epidemics and other phenomena as deterministic (or probabilistic) phenomena within a natural world in which human purpose either has no effect or is itself predetermined.

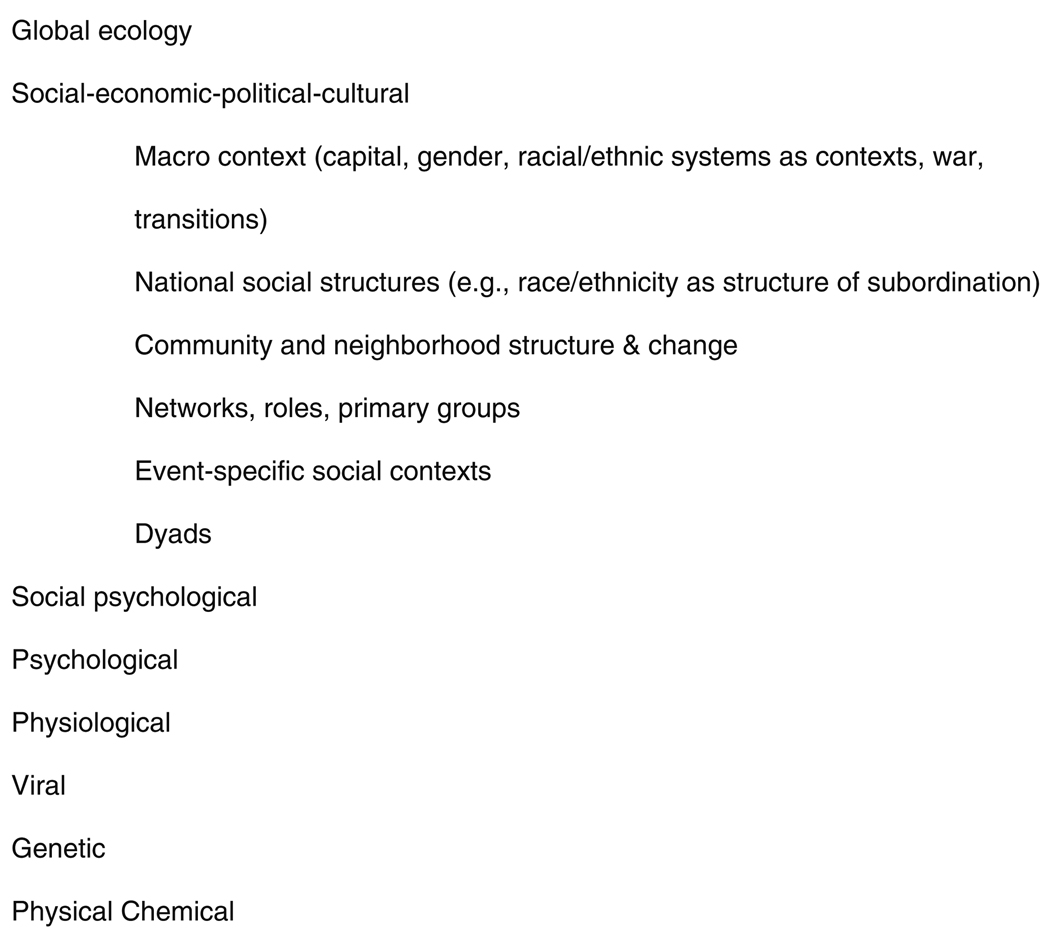

In contrast, “dialectics” refers to a mode of thinking and research that is very different from these assumptions. It sees wholes as fundamental parts of causal systems, change as resulting from reciprocal causation and conflicts within and between levels of analysis (Fig. 1), and emphasizes processes rather than states of being. Here, we would add, the historically enacted reciprocal causation between the socio-ecological and the biological organism at the genetic and bodily level is what evolution is all about.

Fig. 1.

Levels of analysis interact dialectically

Dialectics also sees phenomena, including epidemics, as historical processes that involve contradictory forces. Thus, historical processes tend to evoke their own negation, then these negations evoke their negations, and so forth—and at every point, the existing processes are shaped by the history of these negations. (For mathematical modelers, this then implies that epidemics and other processes are not Markovian), In epidemic history, this is shown by the fact that both viruses and human genomes have been shaped by their interacting histories6, that scientific efforts to fight infections are negated when a virus or bacterium develops resistant strains through selective mutation, and that this negation may then itself be negated by further scientific advance (and so forth). History shaped the public health and scientific responses to HIV/AIDS in many ways, including the facts that the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (a leading agency in this struggle) was deeply shaped by experiences and lessons learned in sexually transmitted disease control efforts and in the smallpox eradication campaigns. CDC ideas and efforts on hepatitis C control, as well as those of many researchers and of drug user activists themselves, were for some years shaped by the lessons learned in HIV campaigns. The development of therapies and the search for vaccines for HIV have been shaped by the fact that companies perform research in pursuit of profits and the structures and approaches of funding agencies like the US National Institutes of Health are oriented around the creation of new commodities to be produced by corporations and then bought by profit-making medical institutions or public health bureaucracies.7 Of course, CDC and broader HIV/AIDS politics have also been shaped by gay struggles and their histories; drug war politics; racial/ethnic, gender and national histories and struggles; and much else.

Another aspect of dialectics that is important for the HIV epidemic is that self implies other. This Hegelian formulation means that seemingly independent and mutually exclusive processes interpenetrate. This can be restated as seeing self and other as an interacting whole (entity) such that they interpenetrate each other. This aspect of dialectics stands in clear contrast to positivistic models that see “billiard ball” variables as acting on each other from the outside. Instead, dialectics holds that the system may best be studied as intermingling opposites that are also the same. On first blush, of course, such language appears mystical. It becomes clearer when fleshed out by examples. Levins and Lewontin, for example, show that organisms and environments are not mutually exclusive, but rather interpenetrate.8 In epidemiology, this is illustrated by the fact that viruses become part of their hosts, and their hosts also become part of the viruses; once infected, a host and its viruses become a unified system with interactions occurring internally. Indeed, immune systems are based on self/other processes—which are central to the evolutionary contest between (a) HIV mutation and recombination and (b) human therapeutics and vaccination development. On an evolutionary level, this interpenetration becomes the case with humanity and the agents that infect it.9

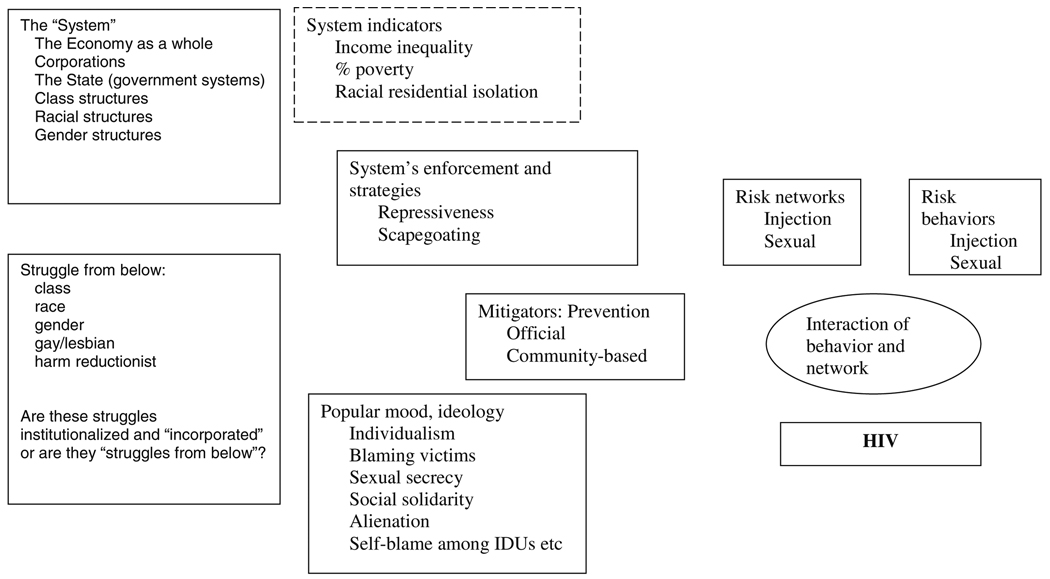

Figure 2 presents another example. This derives from our thinking about how large-scale social structures like governments, economics, and the economy are related to social structures of oppression and exploitation and thence to popular resistance, issues of ideology, sexual networks, prevalence of people who inject drugs in the population, risk behaviors, and viral transmission. Our original thoughts on this were in terms of variables and their causal patterns. As we thought it through more deeply, however, we realized that structures like racism were deeply embedded in governmental and economic structures, that government and economic structures likewise interpenetrated, that struggle from below and popular ideologies and moods are not so much separate as closely interacting processes, and that risk networks and risk behaviors were mutually constitutive of each other.

Fig. 2.

A model of structures, risk, and HIV: But should it be approached with a “billiard ball” model or an “interpenetrating others” model? (An earlier version of this figure appeared in the study Friedman and Reid (2002))

Foster and Smith have presented a “metabolic dialectics” based on wide reviews of the works of Marx and of Engels.10 They see humanity as a part of nature, but as a part that is very active in reshaping both itself and the rest of nature. Smith discusses the large-scale reshaping of nature that humanity has done as having changed “space” and as having created a “second nature.” He and Foster both see capitalism as structuring human labor to reshape nature to products in order to produce profits. These arguments become important later in this paper when we discuss possible ways in which capitalism created social niches in which early HIV strains could become virulent and produce epidemics and also in terms of how it has structured the ideas and practices of HIV prevention.

The final aspect of dialectics that we want to present forms the basis of praxis. It is that human action and thought make history and affect epidemics. People are subjects, not just objects. Thus, epidemics are not deterministic phenomena, but rather historical events that can be changed by human action. Of course, as Marx said, “Men [sic] make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past.”11 We already mentioned the ways in which the history of CDC helped shape its actions in relation to HIV/AIDS; much of the rest of the paper is devoted to showing how this history has unfolded as a process of struggles.

Dialectics of HIV

The metabolic dialectics of the emergence of the HIV epidemic

As mentioned earlier, Ewald discussed the logic of how social and behavioral processes can shape viral evolution.12 Goudsmit further developed these ideas as part of an interpretative review of socioepidemiologic data on HIV and related viruses in primates and humans, and of the history of the HIV epidemic, as then known.13 More recently, de Sousa updates information on the evolution of viral subtypes in the first two-thirds of the twentieth century.14 He considers serial parenteral transmission, urbanization, and migration as possible factors that might have produced viral adaptation and hence an epidemic outbreak, but concludes that these processes are not adequate to explain the biogeography and history of epidemic HIV groups.

Smith’s theory of second nature may provide a framework to help us conceptualize the processes through which HIV became more virulent more adequately than “serial parenteral transmission, urbanization, and migration.”15 The theory of second nature helps us pose the question as what kinds of social niches did capitalist society produce that led the virus toward virulence and epidemic spread? Here, “capitalist society” needs to be understood as a complex and changing entity, and not just as a series of production and exchange relations. It refers to these relations, to be sure, but also to the politics, social interaction patterns, and cultural patterns that historically changing capitalism has produced.

What is at issue here is the social production of social niches and processes in which:

Frequent unprotected sexual or injection risk behavior occurs

among large numbers of people,

some of whom then go on to engage in similar or parallel behaviors in other such niches.

Such a system of interconnected niches would then enable a highly virulent strain of HIV to evolve and then to spread quickly and widely. One or more such events could then establish a global HIV epidemic, and the continued existence of such niches would both provide networks through which HIV epidemics could continue to spread, and locations in which tendencies to evolve less virulent strains could be counteracted. (It is worth noting here that Crum-Cianflone et al. report that initial CD4 counts among 2,174 HIV seroconverters in the USA declined from 1985 to 2007, an indicator of evolution toward more virulence).16

There is considerable evidence that a number of such niches existed in the 1970s, which is the period when a highly virulent global HIV epidemic seems to have become well established. We will review some of what is known about such niches—but warn that our own expertise limits these accounts.

Such a niche connected the injection drug users (IDUs) of New York City in the mid-1970s and later. HIV entered this scene by 1976; epidemic spread began by 1978 or before.17 During and following the civil rights and black power movements, student movements and other movements of the 1960s and early 1970s, and the Vietnam War—all of which can be viewed as part of capitalist dynamics and struggle18—the use of injected heroin and cocaine became relatively widespread in New York. This was a time of Drug War and of severe syringe shortages, so syringes were shared widely and injection occurred in hidden venues.19 As Wallace and Wallace have shown, the New York Fiscal Crisis of the mid-1970s both created increased youthful drug injection and homelessness, and also provided abandoned buildings that became the venues for “shooting galleries.”20 Shooting galleries were spaces in abandoned buildings where local IDUs (often homeless) could inject out of view of neighbors or police. IDUs who lived in other neighborhoods but who came to a given (usually derelict) neighborhood to buy drugs would seek local shooting galleries to inject in. Given the syringe shortage, the managers of shooting galleries would use syringes on hand for their patrons (as well as unused syringes if these were available). This led to an ideal environment for HIV (and other pathogenic) transmission—frequent shared injection behavior among large numbers of people some of whom injected in other neighborhoods either at shooting galleries or with groups of friends (some of whom might go to other shooting galleries). Shooting gallery attendance in the early- or mid-1980s was found to be a strong predictor of HIV infection among New York IDUs.21 Thus, a combination of imperialist war and oppression, a drug war politics introduced in part as a political strategy to help put down the movements,22 and the economic and socio-political dynamics of the capitalist fiscal crisis,23 helped create a niche for rapid viral spread of HIV in the 1970s (and perhaps for viral mutation toward high virulence).

Farmer showed how capitalism and imperialism had created niches for rapid sexual HIV transmission in Haiti.24 He does this by tracing Haiti’s history in terms of its role in world circuits of production and trade, and concretizes this example by showing how the construction of a dam to serve corporate interests displaced a village and led many of its members into migration, sexual liaisons and/or sex trading, which in turn led to their becoming infected with HIV. As he shows, such patterns led to a widespread AIDS epidemic in Haiti by the early 1980s.

The story of such niches in the gay communities of the USA and other countries has not, insofar as we are aware, been told in terms of how capitalism created the relevant niches. Many of the raw materials for such a study do exist, however. Auerbach et al. described the sexual networks through which HIV may have spread among gay men in and among US cities in the late 1970s and early 1980s.25 Levine provides detailed sociological perspectives on the internal dynamics of the “clone culture”—a niche in which viral evolution and/or spread could easily have occurred.26 Barry Adam has described the rise of gay communities and social movements; his work together with that of Dennis Altman presents the materials from which to put these niches and processes into the framework of capitalism and its dynamics.27

The dynamics of prostitution and of institutionalized systems of concurrent sexual partnerships in some of the cities and towns of Central and East Africa also seem to have provided such a niche.28 Gisselquist et al. have suggested that the sharing of syringes for medical purposes in underfunded clinics may also have been a key ingredient in these niches—although this argument has been contested.29 Stillwaggon has suggested that widespread malnutrition and exposure to helminth (worm) infection—both of which are products of the extreme poverty of many Africans in these regions—greatly facilitated HIV transmission as well.30 Although we are not aware of any studies that have shown this argument in detail, these data seem to suggest that the following is a reasonable way to incorporate the African cases into our overall argument—although further research is clearly needed to prove the point.

Capitalism developed in part through the use of African slaves in the Western hemisphere and in the merchant fleets and navies of European powers as cheap labor.31 Full colonial control was established by the Europeans over most of the Central and East African area during the 1800s, and was contested and defeated during the 1940s through the 1960s, although European and American capital maintained substantial economic control and political influence thereafter. This led to lasting—and indeed deepening—poverty, malnutrition, exposure to helminthes, and underfunded medical systems in much of the area. Thus, prostitution and unsafe medical injection became widespread; patterns of concurrent sexual relationships developed or were maintained out of the interaction between economic needs, a mixture of traditional cultural patterns, and their interplay in gender-related and other politics.32

Social processes and HIV prevention and continued transmission

In the years since HIV began to spread in New York in 1975 (and perhaps other countries before then), the dialectical processes of human history have clearly shaped it. On the microsocial level, drug users in New York may have been the first to recognize the existence of the new plague, and their responses to it seem to have slowed its spread well before medicine recognized its existence (Fig. 3). This exemplifies and illuminates a key element of the Marxist dialectic—that even the most oppressed maintain a degree of human agency and initiative. In this case, we see that injection drug users, based on what they saw happening to each other and themselves as elaborated in conversations with each other, figured out that there was a new fatal disease approximately 2 years before science “discovered” AIDS and, unaided by science or public health input, developed behavioral strategies to reduce the spread of this new disease.33 Many of these drug injectors were seriously addicted to heroin and other drugs; all were under heavy repression by the police; almost all faced stigmatization by their neighbors and family members because of their drug use; most were quite impoverished; and many were Blacks or Latinos who faced racial/ethnic oppression as well as oppression as drug users. Furthermore, the racially/ethnically oppressed injectors were particularly likely to reduce their HIV risk.34 The point bears repeating: In spite of all these obstacles, the dialectic spark of resistance was strong enough to let them act with some success against the new virus.

Fig. 3.

History of the HIV epidemic among injection drug users in New York City and of the response by injectors, medicine, and public health. Adapted and updated from figure in the study by Friedman et al. (2007)

Injection drug users in New York are by no means the only group that has acted against the epidemic. Injectors in Rotterdam in the Netherlands had already organized as a public interest and protest group, and they took collective action to save each other from AIDS. Later on, injectors in Buenos Aires and in Central Asia also acted to resist the virus,35 as have users in India, Indonesia, Thailand, Russia, and many other countries.

Gays, often aided or even led by lesbians, set up campaigns to resist the spread of HIV, to care for the sick, and to influence medical and social policy. Although this began in a few urban centers in wealthier countries, similar groups soon sprang up around the world—often in the face of serious oppression of gays.

Similarly, sex workers organized for similar purposes around the world. Indeed, one of the most successful efforts to prevent HIV transmission was the organizing of sex workers in Calcutta to enforce safer sex requirements on brothel owners, customers, and sex workers themselves. This project has reduced HIV and STI transmission to, among, and from sex workers there.36 Women sex workers began to organize in Argentina in 1994. (The nineties were the decade in which neoliberal policies were imposed in Argentina). In 1995 their union, AMMAR, joined one of the central federations of unionized workers in Argentina. They have been very active against repressive activities against sex workers.37

Under capitalism, of course, social movements face strong pressures to become alienated from their roots and thus negated. This happened with the Second International38, the Russian Revolution39, and many more recent movements by workers,40 as well as other movements such as those by Blacks in the United States in the 1960s.41 This also happened with many AIDS-related movements and organizations, in which the funding advantages of non-governmental organization legal forms (with boards of directors rather than memberships as decision-making bodies) and/or the simple political pressure to accept reformist or bureaucratic limitations in exchange for support and funding led many gay, sex worker, and harm reduction groups to become service-providing NGOs.42

Macrosocial dialectics also shaped the epidemic.43 Most clearly, existing structures of exploitation and oppression that have developed through the outcomes of generations of capital expansion and the politics of imperialism and oppression structured the spread of the virus. For example, in the USA, HIV became most prevalent among Blacks early in the epidemic, and this has remained true for decades.44 HIV also spread early to Haiti, driven by patterns of imperial impoverishment and by sexual tourism by middle class and wealthy gay men from the USA before they were aware of the epidemic.45 HIV spread most widely in Africa, the poorest and most marginalized and malnourished continent, and its impact there was heightened by neoliberal economic policies and post-colonial patterns of transportation, government, and labor migration.46 Epele and Pecheny have described how capitalist neoliberalism created conditions for the spread of HIV among Argentine communities that it was causing to deteriorate and to become impoverished.47

The history of capitalism has involved many fierce political struggles. In recent decades, this took the form of sociopolitical transitions in a number of countries—with profound epidemic consequences.48 One key example is the social, political and economic crises and transitions of the USSR and the states of Eastern Europe in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Although the causes and implications of these transitions are still deeply controversial on the left, the epidemiologic disasters they created in some (but not all) countries are well known and tragic. In Russia, massive economic decline, loss of hope, and loss of cultural continuity between generations led to widespread alcoholism, malnutrition, and mortality. It also led many youth to take up injection drug use and/or sex work. This, in turn, has led to widespread epidemics of HIV/AIDS and other sexually and blood-borne diseases.49 Other countries such as Ukraine and Uzbekistan have seen similar developments.

The social struggles that ended apartheid in South Africa were followed by the rule of the African National Congress, which accepted neoliberal policies, cut spending on social and medical services, and allowed the pre-existing state bureaucracy to impede what little effort it initially attempted to slow the spread of HIV. This transition was followed by increases in alcohol use, sex work, and drug use—which interacted with pre-existing residential and labor patterns and cultures, poverty, patterns of sexual behavior and interaction, and with the political events just referred to, to enable the massive and rapid spread of HIV/AIDS.50

Similarly, the economic crises and the political transition from the dictatorship in Indonesia led to growing drug use and HIV spread in many parts of the country.51

Not all transitions lead to HIV/AIDS epidemics, however. The Philippines seem to have escaped this despite the popular power uprising and the ousting of Marcos in 1986, the social struggles since then, and the long-lasting guerrilla insurgency in parts of the country. Furthermore, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, and many other Eastern and Central European countries went through transitions but seem not to have developed large-scale HIV epidemics (see UNAIDS website). Thus, transitions do not determine the later coming of HIV epidemics, but they may produce periods of high vulnerability to potential HIV outbreaks. We have been studying the sequelae of the Argentinean economic, social and political crises since 2002 in order to learn more about what happens and how it happens—and, of course, to do what we can to avert an epidemic.52

The crises of capitalism and imperial contradictions often lead to wars. There is considerable controversy over how and when wars have what impacts on HIV. Hankins et al. discussed mechanisms through which war could lead to HIV spread and pointed to worrisome signs among refugees who had fled war to go to Pakistan.53 Strathdee et al. have discussed this in more depth.54 On the other hand, Gisselquist and Spiegel have presented comparative evidence about HIV/AIDS epidemics in Africa.55 They find that wars there have decreased HIV transmission—perhaps through restricting sexual networks.

Increasingly, the politics of HIV response are becoming integrated into Big Power politics and domestic politics in the USA and globally. Thus, all the normal dialectics of consciousness, class, the development of capitalist accumulation and the state, and struggles over axes of oppression have had their place in this epidemic. One form this takes is that those with HIV/AIDS and/or those groups most at risk of HIV (usually, gays, sex workers and/or injection drug users) are attacked and made into scapegoats as a way to divide working class and/or racial/ethnic communities and to distract them with fears of the targeted groups.56 (On the other hand, AIDS politics in some countries have taken an alternative course. The dominant Australian approach has been a strong emphasis on public health against this threat to people’s lives, and this has served to strengthen the ideology of cross-class and cross-group collaboration under the leadership of technical experts and a “benevolent” state that typified the welfare state era. This exemplifies an argument Friedman made: Scapegoating, divide-and-rule responses can take many forms and target different groups, so a given national government can choose not to use AIDS policy as a way to divide potential opponents.)57

Thinking of the epidemic dialectically may help us confront a dilemma that has faced the left (even though some of us may not have realized it) for some time. As Friedman and Reid pointed out in reviewing HIV/AIDS epidemiology in South Africa, Indonesia, and Russia, “transitions” including “festivals of the oppressed” may in this era be haunted by a specter of their own—that of mass outbreaks of HIV that threaten their economic and social cohesion and, at the least, require considerable political and economic attention among the poor and working classes as well as at the level of the state and economy.58

To concretize this, it may be useful to discuss a case in which the epidemiologic outcome is not yet clear—that of Argentina. As Epele and Pecheny have also discussed, an economic crisis driven in part by the political economy of neoliberalism emerged in the early 1990s and produced a rapid increase in unemployment.59 By 2002, official unemployment was 25% and half of the population was below the poverty line. Inflation raged, which meant working class families had trouble meeting basic needs. This economic crisis led in the late 1990s to waves of factory seizures by workers, highway blockages by piqueteros (“picketers”) who were often unemployed workers or other poor persons, and eventually to massive demonstrations by middle class members, students, workers and piqueteros that ousted 4 presidents in late 2001 and early 2002. In terms of our discussion of festivals of the oppressed, these mass demonstrations may have set the stage for an HIV epidemic. Since 2003, Argentina has seen some economic stabilization—although not for most slum dwellers; many people who lost jobs during the economic crisis remain unemployed. Widespread political mobilization and unrest continue.

In recent years, youth violence has increased, particularly homicides in slum areas. Young boys under 18 from slum areas are being scapegoted and presented by the media as a menace to the rest of society by showing their participation in very violent crimes, while many young boys from those areas are being killed by police—who only rarely face trial for these killings.60 Such violence is particularly traumatic in Argentina, a country where many families live with the effects of the dictatorship of 1976–1983. During the dictatorship, thousands of youth and adults were “disappeared” and, in many cases, tortured and/or killed. Their family members were often terrorized into silence. Furthermore, as Bastos et al. have noted, the traumas of the dictatorship period interact with long-term high levels of structural violence, inequity and disrespect for human dignity.61 Thus, youth violence, and the wide news coverage it receives, interacts with these pre-existing traumas to spread fear and alienation among additional youth, which may lead some of them into substance use as a form of self-medication or escape. Other signs of alienation and of a decrease in successful normative regulation of youth include increasing school drop-out rates.62 Drug use and sexual risk taking may also be increasing, particularly in terms of an increase in the use of coca paste (called basuco in Colombia and paco in Argentina) in Buenos Aires.63 Also there is an increase in incarceration of both men and women because of drug-related offenses: most of the imprisoned women are in jail for trafficking small quantities of illegal drugs. Their mean age is 30 years and 90% of them have children.64

One could argue that this alienation of youth, increased drug use, and increased violence and incarceration resemble the pathways by which HIV epidemics broke out in Russia, Ukraine, and South Africa after their transitions. However, the magnitude of those negative developments in Argentina seems to be considerably less than in these countries with their major epidemics. One hypothesis—for which our ongoing research on the post-transition period in Argentina has not yet provided definite answers—is that post-transitional HIV epidemics may be more likely to break out in countries that accept neoliberal policies but may be less likely in areas that avoid such “belt-tightening.”65 Comparative research among a number of post-transitional countries might illuminate this hypothesis; such research should include the Philippines, given the failure of an HIV epidemic to develop there after its transitions. Should the hypothesis that avoiding neoliberal belt-tightening is protective and is supported by the evidence, however, this just poses the political and strategic question of how post-transitional countries are able to resist the pressures to impose neoliberalism. In terms of the discussion of dialectics, it poses the question of the processes by which human agency and struggles can succeed or fail in preventing epidemics.

The dialectics of struggles over HIV prevention ideas and labor

Part of the response process to epidemics is the politics and ideas that guide or dominate the responses. For the HIV epidemic, the response has been guided primarily by ideas that analyze epidemics and societies as being based on individuals and their (self-seeking) behaviors. This was no accident, but rather the result of the early 1980s period when HIV first came to the notice of science and policy makers.

The early 1980s were the age of Thatcher, Reagan, the Russian/Polish crushing of the Solidarnosc uprising in Poland, and right-wing dictatorships in Argentina, Brazil, and Chile. In the United States, a politics based on free-market neoliberalism in economics (rather than the dominant military Keynesian doctrines of 1940s–1976) became dominant in about 1977, and had its dominance confirmed during the Reagan years. At the ideological level, this period and doctrine is characterized by an extreme individualism. In the United Kingdom, Thatcher put this in terms of there being no such thing as society—just individuals. (Of course, even in the earlier period, individualism was an extremely strong ideological current—but it was more tempered by paternalistic ideas of doing good for others and labor—or other movement-based ideas of solidarity.)

The hegemony of radical individualism as a political doctrine had enormous consequences for HIV/AIDS prevention thought. It meant that HIV prevention was seen in terms of changing the behavior of risk-taking individuals. It also meant that prevention messages and epidemiologic research were very much focused on protecting the “me.” Hence, people were told to use condoms to protect themselves against HIV, and epidemiology and prevention research both focused on risk factors for the subject (the “me”) becoming infected. Parallel to this, individuals were seen as adequately portrayed for the purposes of HIV prevention as bundles of behaviors. A given “me” might be characterized as having sex with a man 4 times a week, never using condoms, and injecting drugs (though only with sterile needles) once every 6 months.

The response to HIV among drug users in the USA and Argentina (but not in some other countries such as the UK and Australia) became enmeshed in Drug War politics that were in large part promulgated as part of a “divide-and-rule” political response to the movements of the 1960s and 1970s. (The “war on drugs” also led to increases in the number of persons imprisoned on drug-related charges in the USA and in each South American country, including Argentina.)66

These politics saw drug use as the result of bad choices—so that Nancy Reagan’s “Just say no” was seen as an appropriate slogan for this public health issue. This was part of a broader culture of personal responsibility and seeing the solution to all problems in terms of finding someone to blame for them—an approach fully supported by the mass media’s emphasis on prime time police/crime dramas in which all is made right at the end of the show when the perpetrator is arrested and imprisoned.67

The struggle against HIV has also been guided by dominant ideas about public health and indeed all public services—that they have to be run efficiently and effectively.68 This represents a politics of belt-tightening based on a period of increased capitalist competition when compared with the 1950s and 1960s. This increased competition has been variously analyzed as a result of globalization of production or of a lower rate of profit.69 In neoliberal ideology, furthermore, government expenses are seen as non-productive and as a drag on the profit-making economy. This focus on efficiency and measurable effectiveness, then, has interacted with the behavioral individualism of dominant thinking about HIV to shape the ways in which government agencies and others want HIV prevention activities to be conducted.

In part, this takes the form of limitations on what will be funded. In the USA, most HIV prevention takes the form of individually focused HIV counseling and testing or, alternatively, of a series of “Evidence-Based Interventions” (EBIs) that involve counseling and other individual interventions or small-group educational events to reduce or prevent risk behaviors. (These EBIs are seen as ideally based on individually randomized clinical trial experiments in which the intervention arm reduces or prevents risk behaviors more than the control arm). This, of course, makes it hard to get funding for interventions that focus on social structures or the collective self-organization of sex workers (as in the Sonigachai Project in Calcutta), gay men, or drug users.

The dominant prevention models go even further to control what happens, in many cases. EBIs and most prevention research projects place a major premium on interventions being “manualized” to assure their fidelity of application in the field. The dominant interpretation of manualization is that it enables funders to make sure that the actual intervention is faithful to that which was tested scientifically. Another way to look at this, however, is as a form of labor control—that is, as a way to make sure that initiative and creativity on the part of front-line workers are minimized and that thought and initiative remain under the control of managers. In our experience, local front-line workers resent this external control over their activities at work, and seek ways to do their work in what they think are more appropriate ways that match the needs of the specific people they are counseling or teaching. Such struggles over the nature of the work process are, of course, a characteristic of all capitalistic labor.70 In this case, however, it is important to note that EBIs, manualization, and similar mechanisms both control the labor process of the front-line workers and also restrict the initiative of community-based organizations that might prefer to use more collective or solidaristic prevention approaches.

Although some organizations of gay men, sex workers or drug users who are involved in HIV-related struggles have adopted these top-down ways of thinking and acting, others continue to fight for more social ways of thought and for letting front-line workers use initiative and creativity in helping those they serve or represent. Meetings between government funding officials and community organizations usually involve a degree of acceptance by all participants of the need for “community participation and involvement,” but this is usually accompanied by a degree of struggle over the relative power of the community agencies to control what they actually do. In our experience, this often involves some degree of challenge to both the individualism of most “evidence-based” interventions and to the attempt to control the daily activities of front-line workers—but the power remains in the hands of the funders.

Struggles for access to HIV medicines

Capitalism currently conducts almost all pharmaceutical production through profit-seeking corporations. Indeed, in recent years, these corporations have been among the most profitable firms in the economy. This has led to struggles over the prices of HIV medications as well as struggles over the resources devoted to finding new treatments and prevention technologies. In countries like the United States where patients (or insurance companies) pay the price of drugs, struggles over access to HIV medicines have sometimes taken the form of demands that government programs pay for them. These demands were successfully incorporated into the Ryan White program in the United States—but the recent economic crisis has led to serious cut-backs in many states that mean that many people will lack access and, perhaps, die as a result.

In several Latin American countries, including Argentina, antiretroviral therapy (ART) is available through the public sector. High pharmaceutical prices, however, can make it very difficult for governments of these countries and those of the rest of the “global South” to provide these medications to the populations. Struggles have broken out when governments such as that of Brazil, confronted with these costs and with the political necessity to pay for them out of government funds, have invoked public health emergency exceptions to international patent and intellectual property rights regulations in order to produce generic antiretroviral medicines and make them available to those who need them. Even in these countries, however, treatment is not always free of charge. Collateral fees represent a particular barrier for poor people with HIV or AIDS, particularly among those who are drug users.

Medicine in capitalism has always been plagued with the problem of how to keep companies from producing and marketing useless or even harmful products under the guise of medications to help the sick. Earlier struggles over this led to government programs to approve and regulate medications such as the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Important struggles over FDA policies occurred in the late 1980s and succeeding years when primarily gay people with AIDS and their allies successfully demanded that the FDA speed up the approval of promising drugs.71

Drug users have faced particularly acute problems of gaining access to medications they need. In South America, while there are no official policies preventing drug users from receiving antiretroviral treatment (ART) for HIV, drug users face many informal difficulties.72 Health care workers’ attitudes and misconceptions have limited users’ access.73 For example, many health care providers fail to distinguish between different modes of drug use (dosage, frequency, and circumstances of drug use), judging all drug users by a single standard and often requiring that they seek abstinence-based drug treatment before beginning ART. Additionally, they may consider drug users to be self-destructive and unconcerned about their health.74

Similar attitudes by doctors and by public authorities similarly limited access to ART in the United States, Russia, and many other countries until the last few years. This was echoed for many years by a formal ban in the USA (and elsewhere) on providing current drug users with treatments for hepatitis C infection. (Hepatitis C is a debilitating and often-fatal chronic infection that large majorities of injection drug users have acquired through their syringes. Co-infection with HIV and hepatitis C causes disease to progress more rapidly and also increases the odds of death).

Another parallel access problem that drug users face has been limited access to methadone, an opiate that is administered to help them stabilize their lives. Methadone treatment has been shown to reduce the probability that drug users will become infected and to make it more likely that they can successfully adhere to ART for HIV and to treatment for hepatitis C. Despite this, in many countries, including Russia, methadone is banned by the state, and in others, access is highly restricted.

Struggles for drug users’ access to these medicines have occurred for decades. Sometimes they are led by drug users’ own organizations, as took place successfully through Dutch users unions organizing a system of underground methadone access to pressure the official system to provide adequate doses in the early years of the HIV epidemic. Other times, public health, and medical professionals in alliance with NGOs like harm reduction organizations play a leading role. Such an alliance was successful in defeating the ban on users’ access to hepatitis medications.

Summarizing this section on access, there has been a complex dialectic among pharmaceutical companies, states, public health professionals, and those at risk for or living with HIV/AIDS. Struggles have broken out over regulations that limit drug development, the cost of medications, and whether drug users, stigmatized in part because they can be successfully stigmatized as a divide-and-rule strategy to weaken social opposition movements to capitalism or to particular problems it produces, can gain access to medications. In general, however, these struggles have involved relatively limited numbers of participants and have not in themselves posed a serious threat to the state or to capitalism.

A dialectics of nature?

On another level, HIV poses an example where concepts of a “dialectics of nature” may be useful. This is a controversial assertion and one that we are only in the process of exploring. Although we tend to agree with criticisms by Lukacs and others of the way Engels treated examples of change as dialectical, like Levins and Lewontin, we also see ways in which epidemiologic and ecological processes might be understood as dialectical.75

One key element in this dialectical interpretation is that the rapidity of mutation of HIV means that its responses to medical and social interventions against it mimic those of a strategic intelligence. Medicine has developed potent combinations of antiretroviral therapies that have reduced AIDS mortality greatly among patients who have consistent access to them. Nonetheless, HIV mutates sufficiently rapidly to develop resistant strains—and indeed, this has led to a situation where medicine is in a continual race to develop new therapies before the virus outstrips them, and we cannot know the outcome of this race.76 Similar races are taking place between medicine and other diseases such as tuberculosis, gonorrhea, malaria, and staphylococcus (which has led to hospital outbreaks by resistant strains). Furthermore, this race extends to the related conflict between human efforts to destroy insect vectors of disease (such as the mosquitoes that bring malaria, dengue and many other diseases to human bodies) and the ability of these animals to develop resistance to insecticides. Aspects of social change, such as the ways in which neoliberal impoverishment multiplies stagnant water in shantytowns and the ways in which global warming encourages mosquito spread and survival, may add additional interactions to this dialectic and help these epidemics to spread.

Sociobehavioral weaknesses in the human defense against HIV are seized by the epidemic to spread to new geographic areas. Thus, when sexual transmission was clearly failing to bring about epidemic conditions in China, Central Asia, Russia, and parts of Eastern Europe, the virus was able to take advantage of the spread of injection drug use in these areas to enter them in force.

There are other ways in which HIV raises issues of a possible dialectics of nature. When the virus enters the body of a person, it becomes part of her/himself. Indeed, upon entering into a CD4 or other cell, the RNA of the virus becomes integrated into the genetic makeup of the person. In this sense, HIV becomes part of the self. On the other hand, immune systems have evolved precisely so as to be able to identify such invaders as “not-self” and then to attack them. Thus, there is a clear interpenetration of opposites of the self and the virus, and the ensuing battle for dominance or for equilibrium might usefully be viewed as a dialectically unfolding conflict. (To do so systematically, however, is beyond the competence of the authors of this paper).

Implications of this paper for practice

This review of the dialectics of epidemics has implications for practice of various kinds. First, perhaps, is an important dialectical message for us all: The various parts of the whole are interrelated in many ways. For epidemiologists and public health practitioners, this means that an epidemic combines causes that are effects and effects that are causes at many levels of analysis, including the viral/bacterial, the immunologic, the psychological, the social and the socioeconomic/political formation. For the political activist, it means that the problems faced by workers and others are not readily pigeonholed as economic, social, medical and so forth, and that we should find ways to relate to movements like those around HIV/AIDS and make them part of broader movements for social change—without shrinking from the issues raised by epidemics.

In terms of HIV/AIDS, we suggest that such a broad perspective is needed. In many ways, the virus is beating humanity. Although medications exist that hold it in check, more people get infected each year than start using these medications—particularly in poorer countries; the ability of the virus to mutate and escape control continues to endanger the medical gains we have made to date and could become more of a problem if global economic problems interfere with research, production, or distribution of medicines.

In terms of dialectics, we think that the social dialectic cannot in and of itself provide as much insight into epidemics and the struggle against them as a dialectic that considers the social together with the interactions of virology, bacteriology, immunology, and the dynamics of evolutionary mutation. We think that this implies that there is to some degree a dialectics of nature—but remain unsure how far we want to walk down this path. At the very least, this topic needs further discussion.

The dialectical creativity and action manifested by heavily oppressed injection drug workers, sex workers, gays, and lesbians carries a crucial lesson for all of us. Do not write people off as active participants in their own fates, in humanity’s future, or in social struggles. For us, at least, one of the core elements of any dialectics is negation, one of the meanings of which is that the beaten-down sometimes fight back.

Another element of negation is the ways that social formations structure negation and contradiction together. This can be expressed in terms of groups of people experiencing shared structural positions that necessarily attack their personhood, dignity, and ability to meet some or all of their needs (which are themselves shaped by the system). Class relationships are the clearest example of this, but so also are relationships of race, gender, or other forms of oppression and/or alienation as historically structured. In each case, these relationships produce some categories of people who gain off of the sufferings of others. To those of us on the left, this is something we know very well in the usual political contexts. When extended to HIV or presumably other epidemics; however, this often gets forgotten, even by those who ostensibly know all about negation and contradiction. Thus, we have often heard people—including leftists—who support prevention programs like syringe exchange or teaching youth about homosexuality, say things like, “Who could oppose these actions that save lives and reduce harm? The opponents of this policy must not understand the issues—so what is needed is to educate them.” Such statements fail to consider whether the systemically structured needs of the powerful depend upon the risks or suffering of the exploited and/or oppressed. They distract attention from the ways in which powerful actors in the system, and perhaps system stability, benefit from the misery, and even the sickness and deaths, of drug users, sex workers and gays. We have discussed this at length.77

One sobering reflection on our experiences with the HIV epidemic, and on the histories of other epidemics, is that not all contradictions get resolved in timely fashion. We see the HIV epidemic, as it has unfolded historically, as greatly worsened by the contradictions of capitalism which have made it difficult to get affordable medicines to the sick; that have generated anti-scientific (but perhaps politically astute) policies that forbid discussion of condoms, provision of sterile syringes to drug injectors, deny that HIV is the cause of AIDS, and that scapegoat those who become infected or are at risk of becoming infected; and that promulgate individualistic and medically oriented ways of thinking about the epidemic that greatly hamper prevention efforts. We see the contradictions of capitalism as getting worse in coming decades due to the ecological crises including global warming and the long-festering economic crises—to say nothing of imperial conflicts over water, oil, gas and other energy sources. In this context, HIV/AIDS may continue to spread, and other “emerging infections,” including escape mutations of previously tamed diseases like malaria, tuberculosis, and staphylococcus, may cause enormous suffering and death over many years.

The point of epidemiology, as of Marxism, is not merely to study the world, but to change it. Through an interaction of learning together and struggling together, public health intellectuals (wherever they are based and whatever their educational qualifications) and activists (wherever they are based and whatever their educational qualifications) can and should try to make things better and, ideally, help all struggles contribute to creating system transformation. In its maximal formulation, this could take the form of strugglers against epidemics becoming part of revolutionary movements that overthrow the state and seize the workplaces. Note, however, that this would just open a new phase in the dialectic.78 It also creates new contexts for the struggle against the HIV epidemic, particularly since the history of post-transition HIV outbreaks poses the possibility that revolutions, as “festivals of the oppressed”, might unleash new outbreaks of the virus.79

Above all, we see the need for humanity to get out of the stranglehold of capital. This is so for many reasons that are familiar to us all. To those reasons, we would add that this paper suggests that capitalism helps epidemics to breed and to spread, and that those who are mobilized in the struggles against epidemics might be important contributors to the ideas and the force of the struggle for change.

Acknowledgments

A number of people have given us useful feedback on this article. These include Richard Levins, Peter Taylor, Paul Ewald, the Teaching Team of the Seminar of AIDS of the School of Social Sciences of the University of Buenos Aires. Useful feedback also was obtained from attendees at the 42nd Annual Don W. Gudakunst Memorial Lecture of the Department of Epidemiology at the University of Michigan, 2005 and at a presentation at the International Institute for Research and Education in Amsterdam, 2008. The authors would like to acknowledge support from US National Institute on Drug Abuse projects R01 DA13128 (Networks, Norms, and HIV/STI Risk among Youth), its supplement (Networks, Norms & Risk in Argentina’s Social Turmoil), and P30 DA11041 (Center for Drug Use and HIV Research). This research was also supported by a Fogarty International Center/NIH grant through the AIDS International Training and Research Program at Mount Sinai School of Medicine-Argentina Program (Grant # D43 TW001037) and by the Buenos Aires University, UBACyT SO44.

Footnotes

Anderson (1995), Dunayevskaya (1958, 1973, 1981, 2002), James (1980), Lenin (1972), Levins and Lewontin (1985), Lewontin and Levins (2007), Lukacs (1972, 1975), Marcuse (1960), Ollman (1993).

Contributor Information

Samuel R. Friedman, National Development and Research Institutes, Inc, New York, NY, USA, friedman@ndri.org

Diana Rossi, Intercambios Civil Association and Buenos Aires University, Buenos Aires, Argentina, drossi@intercambios.org.ar.

References

- Allen Robert L. Black awakening in capitalist America: An analytic history. New York: Doubleday; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Adam Barry D. The rise of a gay and lesbian movement. Revised edition. Social movements past and present series. New York: Twayne Publishers; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Altman Dennis. AIDS in the mind of America. Garden City, New York: Anchor Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Kevin. Lenin, Hegel, and Western Marxism. Chicago: University of Illinois Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Aral SO, St Lawrence JS. The ecology of sex work and drug use in Saratov Oblast, Russia. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2002;29(12):798–805. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200212000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argentine Federal Penitentiary Service. Reports of the Penitentiary System (June 2003–June 2005, 2006, 2007) 2007 Available at: http://ppn.gov.ar.nwd-online.com.ar/system/contenido.php?id_cat=5.

- Asociación de Mujeres Meretrices de la Argentina (AMMAR) [Accessed 1 July 2009];2009 Available at: http://www.ammar.org.ar/

- Auerbach DM, Darrow WW, Jaffe HW, Curran JW. Cluster of cases of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome: Patients linked by sexual contact. American Journal of Medicine. 1984;76:487–492. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(84)90668-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett Tony, Whiteside Alan. AIDS in the twenty-first century: Disease and globalization. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bastos FI, Caiaffa W, Rossi D, Vila M, Malta M. The children of Mama Coca: Coca, Cocaine and the fate of harm reduction in South America. The International Journal of Drug Policy. 2007;18(2):99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayón MA. Social precarity in Mexico and Argentina: Trends, manifestations and national trajectories. CEPAL Review. 2006;88:125–143. [Google Scholar]

- Binstock G, Cerrutti M. Carreras truncadas: el abandono escolar en el nivel medio en la Argentina. Buenos Aires: UNICEF; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Braverman Harry. Labor and monopoly capital. New York: Monthly Review Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner Robert. The economics of global turbulence. New York: Verso; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- CDC (US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) Fact sheet: HIV/AIDS among African Americans. 2007 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/aa/resources/factsheets/aa.htm.

- Cohen C. The boundaries of blackness: AIDS and the breakdown of black politics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Crum-Cianflone N, Eberly L, Zhang Y, Ganesan A, Weintrob A, Marconi V, Barthel RV, Fraser S, Agan BK, Wegner S. Is HIV becoming more virulent? Initial CD4 cell counts among HIV seroconverters during the course of the HIV epidemic: 1985–2007. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009;48(9):1285–1292. doi: 10.1086/597777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Melo AC, Caiaffa WT, César CC, Dantas RV, Couttolenc BF. Utilization of HIV/AIDS treatment services: Comparing injecting drug users and other clients. Caderno de Saúde Publica. 2006;22(4):803–813. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2006000400019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa João Dinis. Pandemic HIV-1: Its old origin and overlooked mysteries. AIDS Reviews. 2009;11:52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Friedman SR, Novick DM, Sotheran JL, et al. HIV-1 infection among intravenous drug users in Manhattan, New York City, from 1977 through 1987. JAMA. 1989;261(7):1008–1012. doi: 10.1001/jama.261.7.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond J. Guns, germs, and steel: The fates of human societies. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dunayevskaya Raya. Marxism and freedom. New York: Bookman; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- Dunayevskaya Raya. Philosophy and revolution. New York: Dell; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Dunayevskaya Raya. Rosa Luxemburg, Women’s Liberation, and Marx’s philosophy of revolution. Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey: Humanities Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Dunayevskaya Raya. The power of negativity. New York: Lexington; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Engels Frederick. Dialectics of nature. New York: International Publishers; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Epele María, Pecheny Mario. Harm reduction policies in Argentina: A critical view. Global Public Health. 2007;4:342–358. doi: 10.1080/17441690701259359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein Steven. Impure science: AIDS, activism, and the politics of knowledge. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald Paul. Evolution of infectious disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Farber Samuel. Before Stalinism. The rise and fall of Soviet democracy. New York: Verso; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer Paul. AIDS and accusation: Haiti and the geography of blame. Los Angeles: University of California Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Foster John Bellamy. Marx’s ecology: Materialism and nature. New York: Monthly Review Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR. Teamster rank and file. New York: Columbia University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR. Worker opposition movements. Research in Social Movement, Conflicts, and Change. 1985;8:133–170. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Des Jarlais DC, Sotheran JL, Garber J, Cohen H, Smith D. AIDS and self-organization among intravenous drug users. International Journal of the Addictions. 1987a;22:201–219. doi: 10.3109/10826088709027425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Sotheran JL, Abdul-Quader A, Primm BJ, Des Jarlais DC, Kleinman P, Mauge C, Goldsmith DS, El-Sadr W, Maslansky R. The AIDS epidemic among Blacks and Hispanics. Milbank Quarterly. 1987b;65:455–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR. The political economy of drug-user scapegoating—And the philosophy and politics of resistance. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy. 1998;5(1):15–32. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Curtis R, Neaigus A, Jose B, Des Jarlais DC. Social networks, drug injectors’ lives, and HIV/AIDS. New York: Kluwer/Plenum; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman Samuel R, Southwell Matthew, Crofts Nick, Paone Denise, Byrne Jude, Bueno Regina. Harm reduction—A historical view from the left: A response to commentaries. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2001;12:259–263. doi: 10.1016/s0955-3959(01)00063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman Samuel R, Reid Gary. The need for dialectical models as shown in the response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. 2002;22:177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Kippax SC, Phaswana-Mafuya N, Rossi D, Newman CE. Emerging future issues in HIV/AIDS social research. AIDS. 2006a;20:959–960. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000222066.30125.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman Samuel R, Rossi Diana, Flom Peter L. “Big events” and networks: Thoughts on what could be going on. Connections. 2006b;27(1):9–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Cooper HLF, Tempalski B, Keem M, Friedman R, Flom PL, Des Jarlais DC. Relationships of deterrence and law enforcement to drug-related harms among drug injectors in U.S.A. metropolitan areas. AIDS. 2006c;20(1):93–99. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196176.65551.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman Samuel R, de Jong Wouter, Rossi Diana, Touzé Graciela, Rockwell Russell, Jarlais Des, Don C, Elovich Richard. Harm reduction theory: Users culture, micro-social indigenous harm reduction, and the self-organization and outside-organizing of users’ groups. International Journal on Drug Policy. 2007;18:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman Samuel R, Rossi Diana, Phaswana-Mafuya Nancy. Globalization and interacting large-scale processes and how they may affect the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In: Pope Cynthia, White Renée, Malow Robert., editors. HIV/AIDS: Stories of a global epidemic (working title) New York: Routledge, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman Samuel R. Making the world anew in a period of workers’ council rule. We! Magazine #63, Volume 2, Number 18, Wednesday, 2 April 2008. 2008 http://www.mytown.ca/we/friedman.

- Friedman SR, Cooper HLF, Osborne A. Structural and social contexts of HIV risk among African-Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2009a;99:1002–1008. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.140327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman Samuel R, Rossi Diana, Braine Naomi. Theorizing “big events” as a potential risk environment for drug use, drug-related harm and HIV epidemic outbreaks. International Journal on Drug Policy. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangopadhyay Dwijendra Nath, Chanda Mitra, Sarkar Kamalesh, Niyogi Swapan Kumar, Chakraborty Sekhar, Saha Malay Kumar, Manna Byomkesh, Jana Smarajit, Ray Pratim, Bhattacharya Sujit Kumar MD, Detels Roger. Evaluation of sexually transmitted diseases/human immunodeficiency virus intervention programs for sex workers in Calcutta, India. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2005;32(11):680–684. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000175399.43457.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisselquist David, Potterat John J, Brody Stuart. Running on empty: Sexual co-factors are insufficient to fuel Africa’s turbocharged HIV epidemic. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2004;15:442–452. doi: 10.1258/0956462041211216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisselquist D. Impact of long-term civil disorders and wars on the trajectory of HIV epidemics in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance (1) 2005 doi: 10.1080/17290376.2004.9724834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudsmit Jaap. Viral sex: The nature of AIDS. New York: Oxford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hankins Catherine A, Samuel R Friedman, Tariq Zafar, Steffanie A Strathdee. Transmission and prevention of HIV and STD in war settings: Implications for current and future armed conflicts. AIDS. 2002;16:2245–2252. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211220-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman Chris. A people’s history of the world. London: Bookmarks; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Henman AR, Paone P, Des Jarlais DC, Kochems LM, Friedman SR. From ideology to logistics: The organizational aspects of syringe exchange in a period of institutional consolidation. Substance Use and Misuse. 1998a;33:1213–1230. doi: 10.3109/10826089809062215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henman AR, Paone D, Des Jarlais DC, Kochems LM, Friedman SR. Injection drug users as social actors: A stigmatized community’s participation in the syringe exchange programs of New York City. AIDS Care. 1998b;10:397–408. doi: 10.1080/09540129850123939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Centre for Prison Studies. Prison brief for Argentina. 2008 Available at http://www.kcl.ac.uk/depsta/law/research/icps/worldbrief/wpb_country.php?country=212.

- Iriart C. ‘Capital financiero versus complejo médico-industrial: los desafíos de las agencias regulatorias. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2008;13(5):1619–1626. doi: 10.1590/s1413-81232008000500025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James CLR. Notes on dialectics. Westport, CT: Lawrence Hill; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Kliman Andrew. Reclaiming Marx’s Capital: A refutation of the myth of inconsistency. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kochems LM, Paone D, Des Jarlais DC, Ness I, Clark J, Friedman SR. The transition from underground to legal syringe exchange: The New York City experience. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1996;8:471–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenin Vladimir Ilyich. Collected works: v. 38: Philosophical notebooks. Moscow: Progress Publishers; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Lenin Vladimir Ilyich. Two tactics of social-democracy in the democratic revolution. 1905 http://www.marx.org/archive/lenin/works/1905/tactics/ch13.htm.

- Lenin Vladimir I. Imperialism, the highest stage of capitalism. 1916 [Google Scholar]

- Levine Martin P. Gay Macho: The life and death of the homosexual clone. New York, NY: New York University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs Georg. History and class consciousness: Studies in Marxist dialectics. Cambridge: The MIT Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Lukacs Georg. The young Hegel. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Levins Richard, Lewontin Richard. The dialectical biologist. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin Richard, Levins Richard. Biology under the influence: Dialectical essays on ecology, agriculture, and health. New York: Monthly Review Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Louis Debbie. And we are not saved: A history of the movement as people. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Lune Howard. Urban action networks: HIV/AIDS and community organizing in New York City. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill William H. Plagues and peoples. Garden City, NY: Anchor; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Marais Hein. To the edge: AIDS review 2000. Johannesburg: University of Pretoria Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuse Herbert. Reason and revolution. Boston: Beacon; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Marmor M, Des Jarlais DC, Cohen H, Friedman SR, Beatrice ST, Dubin N, el-Sadr W, Mildvan D, Yancovitz S, Mathur U, Holzman R. Risk factors for infection with human immunodeficiency virus among intravenous drug abusers in New York City. AIDS. 1987;1(1):39–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx Karl. The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon. New York: International Publishers; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Mills C Wright. The new men of power. New York: Harcourt, Brace; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Ollman Bertell. Dialectical investigations. New York: Routledge; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlowicz MP, Zunino Singh D, Rossi D, Touzé G, Wolman G, Bolyard M, Sandoval M, Flom PL, Mateu-Gelabert P, Friedman SR. Drug use and peer norms among youth in a high-risk drug use neighbourhood in Buenos Aires. Drugs: Education, Prevention & Policy. 2010;17(5):544–559. [Google Scholar]

- Pisani Elizabeth. The wisdom of whores: Bureaucrats, brothels, and the business of AIDS. New York: WW Norton & Co.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Quimby E, Friedman SR. Dynamics of black mobilization against AIDS in New York City. Social Problems. 1989;36(4):403–415. [Google Scholar]

- Rangugni V, Rossi D, Corda A, Garibotto G, Caliocchio L, Latorre L, Scarlatta L, Blickman T. El paco bajo la lupa. El mercado de la pasta base de cocaína en el sur. Transnational Institute, Serie Drogas y Conflicto, Documentos de Debate No. 14, ISSN 1871–3408. 2006a Available at: http://www.tni.org/reports/drugs/debate14s.pdf.

- Rangugni V, Rossi D, Corda A. Informe pasta base de cocaína. 2006b Available at: http://www.tni.org/reports/drugs/pbcarg.pdf.

- Rediker Marcus, Linebaugh Peter. The many-headed Hydra: Sailors, slaves, commoners and the hidden history of the revolutionary Atlantic. Boston: Beacon Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes T, Simic M. Transition and the HIV risk environment. BMJ. 2005;331:220–223. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7510.220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwell Russell, Joseph Herman, Friedman Samuel R. New York City injection drug users’ memories of syringe-sharing patterns and changes during the peak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10:691–698. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D, Friedman SR, Touzé G, Pawlowicz MP, Singh D Zunino, Mateu-Gelabert P, Maslow C, Bolyard M, Sandoval M. Drug use and HIV risk in Argentina’s social turmoil. San Juan, Puerto Rico: NIDA International Forum; 2004. p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D, Friedman S, Pawlowicz MP, Zunino Singh D, Touzé G, Bolyard M, Goltzman P, López G, Mateu Gelabert P, Maslow C, Sandoval M. Impact of Argentine crisis on young IDUs and non-IDUs in a high-risk drug use environment in Buenos Aires. Orlando, USA: NIDA International Forum; 2005. p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D, Friedman SM, Pawlowicz MP, Zunino Singh D, Touzé G, Bolyard M, Goltzman P, Mateu-Gelabert P, Maslow C, Sandoval M. Impact of Argentine crisis on drug use trends in poor neighborhoods of the Metropolitan Area of Buenos Aires. Scottsdale, AZ: NIDA International Forum; 2006. p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D, Pawlowicz MP, Zunino Singh D. La perspectiva de los trabajadores de la salud. Serie Documentos de Trabajo, ed. Buenos Aires: Intercambios Asociación Civil y Oficina de las Naciones Unidas contra la Droga y el Delito; 2007. Accesibilidad de los usuarios de drogas a los servicios públicos de salud en las ciudades de Buenos Aires y Rosario. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D, Harris S, Vitarelli-Batista M. At what cost? HIV and human rights consequences of the global “war on drugs.”. New York: Open Society Institute—International Harm Reduction Development Program; 2009. The impacts of the Drug War in Latin America and the Caribbean. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Neil. Uneven development: Nature, capital and the production of space. New York: Basil Blackwell; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel PB. HIV/AIDS among conflict-affected and displaced populations: Dispelling myths and taking action. Disasters. 2004;28:322–339. doi: 10.1111/j.0361-3666.2004.00261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli H, Alazraqui M, Macías G, Zunino MG, Nadalich JC. Muertes violentas en la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. Una mirada desde el sector salud. Ed. Buenos Aires: Organización Panamericana de la Salud; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Spinelli H, Alazraqui M, Zunino G, Olaeta H, Poggese H, Concaro C, Porterie S. [Accessed on 4 December 2006];Firearm-related deaths and crime in the autonomous city of Buenos Aires. Ciênc. Saúde coletiva., Rio de Janeiro, V. 11, N. 2. 2006 Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-81232006000200011&lng=en&nrm=iso.

- Stillwaggon E. AIDS and the ecology of poverty. New York: University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Strathdee SA, Stachowiak JA, Todd CS, al-Delaimy WK, Wiebel W, Hankins C, Patterson TL. Complex emergencies, HIV, and substance use: No “Big Easy” solution. Substance Use and Misuse. 2006;14:1637–1651. doi: 10.1080/10826080600848116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touzé G, editor. Saberes y prácticas sobre drogas. El caso de la pasta base de cocaína. ISBN 987-98893-3-9 Intercambios Asociación Civil – Federación Internacional de Universidades Católicas (IFCU) Buenos Aires: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Trotsky Leon. The revolution Betrayed. New York: Pathfinder; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. [Accessed 09/25/08];Adolescencia. 2008 Available in: http://www.unicef.org/argentina/spanish/children_798.htm.

- Verdú MC. Visiones y actores del debate, ed. G. Touzé, 199–204. III y IV Conferencia Nacional sobre Políticas de Drogas. Intercambios Asociación Civil – Facultad de Ciencias Sociales. Universidad de Buenos Aires; 2008. Juventud y mecanismos de control social. De las drogas al gatillo fácil. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace D, Wallace R. A plague on your houses. New York, NY: Verso; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Weir Stanley Lewis. Class forces in the ‘70’s. Radical America. 1972;7 [Google Scholar]

- Weiss RA, McMichael AJ. Social and environmental risk factors in the emergence of infectious diseases. Nature Medicine. 2004;10:70–76. doi: 10.1038/nm1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinn Howard. A people’s history of the United States. New York: HarperCollins; 2003. [Google Scholar]