Abstract

Background

Older adults often use complementary medicine; however, very few interventional studies have focused on them. The aim of this study was to evaluate the feasibility and to obtain preliminary data on effectiveness of an Integrative Medicine (IM) program compared to usual medical care.

Methods

The study consisted of older adults living in shared apartment communities including caregiving. The shared apartments were cluster-randomized to the IM program or Usual Care (UC). IM consisted of additional lifestyle modification (exercise and diet), external naturopathic applications, homeopathic treatment, and modification of conventional drug therapy for 12 months. The UC group received conventional care alone. The following outcomes were used: Nurses Observation Scale for Geriatric Patients (NOSGER); Assessment of Motor and Process Skills; Barthel Index; Qualidem; Profile of Wellbeing; and Mini-mental State Examination. Exploratory effect sizes (Cohen’s d, means adjusted for differences of baseline values) were calculated to analyze group differences.

Results

A total of eight shared apartment communities were included; four were allocated to IM (29 patients, median seven patients; [mean ± standard deviation] 82.7 ± 8.6 years) and four to UC (29 patients, median eight patients; 76.0 ± 12.8 years of age). After 12 months, effect sizes ≥0.3 were observed for activities of daily living on the NOSGER-Activities of Daily Living subscale (0.53), Barthel Index (0.30), Qualidem total sum score (0.39), Profile of Wellbeing (0.36), NOSGER-Impaired Social Behavior (0.47), and NOSGER-Depressed Mood subscales (0.40). Smaller or no effects were observed for all other outcomes. The intervention itself was found to be feasible, but elaborate and time consuming.

Discussion

This exploratory pilot study showed that for a full-scale trial, the outcomes of Activities of Daily Living and Quality of Life seem to be the most promising. The results have to be interpreted with care; larger confirmatory trials are necessary to validate the effects.

Keywords: Activities of Daily Living, complementary and alternative medicine strategies, NOSGER, older adults, caregiving, apartment-sharing communities, homeopathy

Background

In Western industrialized countries, the proportion of older adults is continually rising. This growing demographic is coupled with an increase of multimorbidity and nursing needs. The increase of patients with cognitive impairments poses a challenge to the health care system: presently, 1.2 million people are suffering from dementia in Germany. It is estimated that this number will increase to more than 1.4 million in 2020 and 2.3 million in 2050.1,2 An increasing number of multimorbid and chronically ill older adults require new concepts in long-term medical care with regard to prevention and therapy.3 In recent years, apartment-sharing communities with integrated care have become a new and more popular residential option among older people in Germany, adding to the traditional choices of late-life residences, such as nursing homes or home care. Usually, a group of older adults or their relatives rent an apartment and hire a caregiving service that provides medical care and assistance for services such as cooking, housekeeping, and other duties. Compared to the bigger nursing homes, this type of daily living is much closer to a usual family life.

To date, the integration of complementary and alternative medicine strategies (CAM) in geriatric care has not been systematically evaluated and tested with regards to feasibility and effectiveness. There are little data available in Germany regarding the use of and the reasons for the use of CAM by older adults. The Germany Allensbach inquiry (2010) highlights that 73% of the elderly population (above 60 years of age) have been using CAM drugs.4 In the US, several surveys were carried out with older adults. A survey by Cheung et al5 with 1,200 participants over 65 years of age showed that around two-thirds (62.9%) applied one or more (on average, three) CAM treatments at the same time. Eighty percent of users reported high satisfaction with these treatments. The maintenance of health and the treatment of health complaints such as arthritis and chronic pain were given as reasons for the use of CAM. Supplements (eg, vitamins and herbs), prayer, meditation, and chiropractics were predominantly applied. In the survey by Ness et al, 88% of those over 65 years of age applied CAM; CAM usage also increased with age.6 The most frequently used CAM treatments were diet and chiropractic/manual medicine. Men applied CAM treatments less often than women. The majority of senior citizens did not inform their doctors about their CAM use and paid for the treatments largely out of pocket.6 A recent systematic review searching for scientific literature about the use of CAM in care in aged residential communities in multiple scientific databases found only five articles, and concluded that very limited descriptive data is available on CAM use in general and much more research is needed due to this gap in information to inform policy and improve clinical practice.7

In theory, CAM therapies might add beneficial components to geriatric medical care because this care relies on lifestyle management strategies such as sports (eg, walking, swimming, gymnastics, yoga, tai chi, qi gong, and others) and nutrition. A complex treatment strategy combining elements of conventional and CAM therapies is called Integrative Medicine (IM). In a recently published study, IM was understood as a transitional term that can aid in removing barriers and opening up medical practice and research towards new forward-thinking health care delivery. Part of this vision is a clear focus on evidence building and patient orientation. IM may be the beginning of a general change from conventional medicine towards a true integration of different medical styles and practices, including an improvement in the patient–practitioner relationship, to ensure that patients receive the best care possible.8

The primary aim of this pilot study was to evaluate the feasibility of an IM program that was developed for older adults living in apartment-sharing communities, and to compare the effects of the program with conventional care. The secondary aim was to determine outcomes that would be suitable for a full-scale trial.

Methods

Design

This study was designed as a two-group, pragmatic, cluster-randomized pilot study. Since the intervention was designed for all inhabitants of an apartment-sharing community, we decided on a clustered randomization to allocate complete apartment-sharing communities to intervention or control. Randomization was carried out centrally by an independent statistician not further involved in the study. The randomized list was based on the “RANUNI” random number generator of the SAS/STAT® software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Each apartment-sharing community received a number and was randomly allocated to intervention or control. The result of the randomization was concealed in an envelope for each apartment-sharing community; the study physicians were allowed to unblind the randomization allocation only after all included patients of a community received a complete baseline assessment of outcome parameters. Each study physician kept a log file with all randomized subjects. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Charité University Medical Center, Berlin, Germany (EA1/118/09; 16.09.2009). The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00974506).

Patients

The study was carried out in eight apartment-sharing communities with integrated nursing care. All older adults, regardless of their diseases and health state, were invited to participate. Older adults were enrolled by the study physicians. We originally planned to include only adults older than 70 years, but we had to change this criterion in the inclusion stage and amend the protocol as it became clear that some of the inhabitants being cared for were younger than 70 years. We excluded only adults in a state of health which would absolutely not permit participation (eg, the patient was dying). All study participants or their legal guardians provided written informed consent before inclusion.

Intervention

The intervention for the IM group was designed by two experienced medical doctors specialized in internal medicine and general practice with further specialization in homeopathy, a naturopath specialized in naturopathic nursing care and self-help counseling, and a sports therapist. The complex IM program was designed with the aim to support self-healing and included lifestyle-changing elements, naturopathic care, and homeopathic treatment.9,10

The intervention took place over 12 months and consisted of:

A weekly 60-minute exercise group, supervised by sport therapists. Exercise included: walking; ergometer training on a MOTOmed viva 2® device (Reck-Technik GmbH, Betzenweiler, Germany); exercise of muscular strength, motoric skills, balance, and coordination; as well as group communication. Patients that could not leave their beds due to disease received individual training in their beds.

Naturopathic care, including the training of nurses by a naturopath about the use of herbal teas, naturopathic wraps and compresses, and the application of herbal massage oils.

Freshly prepared fruit or vegetable juices regularly provided by caregivers.

Individualized homeopathic treatment.

Modification of conventional medication if needed.

The conventional care by family physicians or specialists was continued but the homeopathic study physicians could change conventional medication if necessary; family physicians were regularly informed about these changes, and were asked to contact the study physicians if they disagreed.

The Usual Care group (UC) received conventional, usual care by family physicians, specialists, nurses, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists, without any influence due to the study.

Outcomes and data collection

All patients completed standardized geriatric outcome assessments at baseline and after 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months. Depending on the outcome, the assessments were either performed by a specialized geriatric occupational therapist or by the caregiving community nurse most familiar with the patient.

Multidimensional geriatric assessment: the Nurses Observation Scale for Geriatric Patients (NOSGER) is a validated assessment instrument used in psychogeriatrics, consisting of 30 observable items of behavior and measuring impairments in six areas: memory, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, Activities of Daily Living (ADL), mood social behavior, and disturbing behavior (assessment by nurse).11

Assessment of Motor and Process Skills (AMPS): a validated observational assessment allowing the simultaneous evaluation of motor and process skills and their effect on the ability of an individual to perform complex or instrumental and personal Activities of Daily Living. The AMPS comprised 16 motor and 20 process skill items (assessment by occupational therapist).12,13

Activities of Daily Living: the Barthel Index (BI) is a validated assessment used to refer to daily self-care activities as a measurement of the functional status of a person. It comprises aspects like feeding oneself, bathing, dressing, grooming, and the ability to move on a scale from 0–100 (0, very dependent; 100, not dependent) (assessment by nurse).14

Quality of Life: Qualidem is a validated dementia-specific Quality of Life instrument developed for use in residential care which consists of 37 items, divided in nine subscales regarding care relationship, restless tense behavior, positive and negative effects, positive self-image, social relations, having something to do, feeling at home, and social isolation (assessment by nurse).15

Profile of Wellbeing: this unvalidated assessment tool aims to reflect the wellbeing of residents. Caregivers evaluate the patients’ wellbeing subjectively within 14 indicators regarding signs of positive effects, communication, creativity, activity, cooperation, humor, and self-respect (assessment by nurse).16

Cognition: the Mini-mental State Examination is a 30-point validated test measuring arithmetic, orientation, and memory functions (assessment by occupational therapist).17

Falls: the Tinetti test is a validated test that assesses a person’s static and dynamic balance abilities (assessment by occupational therapist)18 as well as the absolute number of falls (assessment by caregivers/nurse).

Medication list (assessment by nurse and occupational therapist).

Hospital admissions (assessment by caregivers).

Sociodemographic data and disease history (assessed at baseline by the study physicians).

Adverse events and serious adverse events were monitored throughout the study by the caregivers and were critically reviewed by the study physicians and an occupational therapist.

The study physicians were asked to report and discuss their practical experiences and their thoughts on feasibility at the end of the trial.

Data analysis

To our knowledge, this is the first time an IM program including homeopathic treatment has been systematically evaluated. Due to the exploratory design of this study no primary outcome was defined and no formal sample size calculation was performed. The decision to include eight apartment-sharing communities was based on practical feasibility that seemed appropriate according to funding and the personal resources available.

All data analyses were exploratory; 95% confidence intervals were only reported to help with the interpretation of results, not for confirmatory reasons. Each outcome parameter was analyzed separately by generalized linear models, which included treatment group, age, sex, and the respective baseline value as fixed factors and the apartment’s identification as a random factor. Missing values were multiple imputed which resulted in 20 different data sets. Each of the 20 data sets was analyzed separately with the abovementioned models; these results were adequately combined to provide adjusted estimates and 95% confidence intervals.

Results

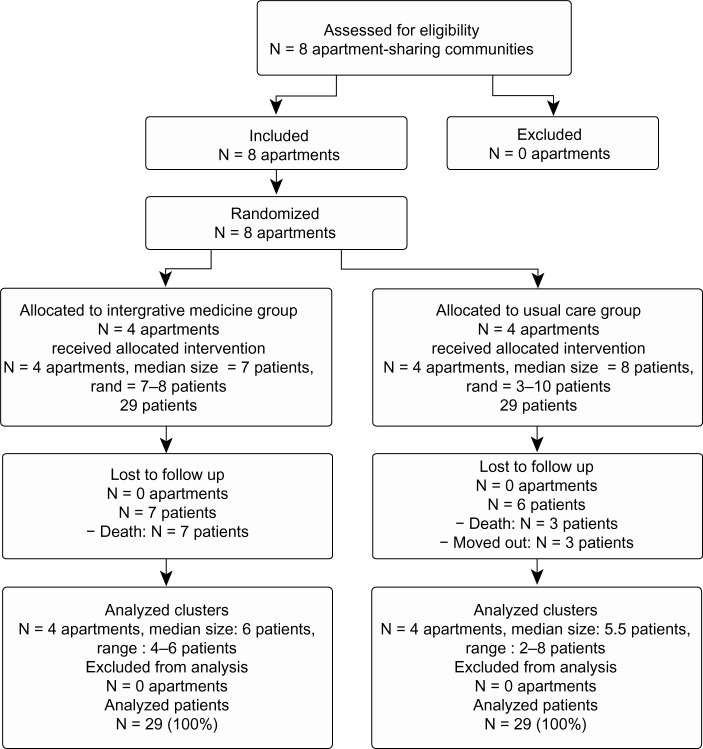

Eight apartment-sharing communities were included; four were randomly allocated to the intervention IM and four to the control UC (Figure 1). The IM group consisted of 29 patients; the median group size was seven patients (range, 7–8), the mean age ± standard deviation of the patients was 82.7 ± 8.6 years (range, 65–102), 25 of 29 patients were female, and 27 had a legal guardian. The UC group consisted of 29 patients; the median group size was eight patients (range, 3–10), the mean age was 76.0 ± 12.8 years (range, 48–99), 14 of 29 patients were female, and 21 had a legal guardian. In the 12-month study period, seven patients in the IM group were lost to follow-up due to death; in the UC group, six patients were lost to follow-up, three due to death and three due to moving out of the apartment. Data on all patients were analyzed following an intention-to-treat approach.

Figure 1.

Trial flow chart.

At baseline, IM patients were on average 7 years older (82.7 ± 8.6) than UC patients (76.0 ± 12.8, Table 1) and were mainly female (86.2% versus 48.2%). Patients in both groups were typical geriatric patients with a high number of multiple diseases and multiple drug treatments. IM patients used 7.0 (±3.4) different drugs daily, compared to UC patients (9.6 ± 2.9). The percentage of patients with cognitive impairments and the number of classified diseases were comparable in both groups.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic data and characteristics of patients at baseline in both study groups

| Integrative Medicine group (n = 29) | Usual care group (n = 29) | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Age, years (± SD) | 82.7 (±8.6) | 76.0 (±12.8) |

| Female, n (%) | 25 (86.2) | 14 (48.2) |

| Legal guardian, n (%) | 21 (72.4) | 27 (93.1) |

| Disease history | ||

| Maximum level of care, n (%) | 7 (24.1) | 3 (10.3) |

| Number of ICD diagnoses, mean (± SD) | 9.9 (±2.9) | 9.6 (±2.9) |

| Cognitive impairment, n (%) | 16 (55.1) | 14 (48.2) |

| Apoplectic insult history, n (%) | 2 (6.8) | 6 (20.6) |

| Number of drugs taken, mean (± SD) | 7.0 (±3.4) | 9.6 (±2.9) |

In the IM group, the mean number of conventional drugs per patient was reduced from 6.8 ± 3.3 at baseline to 4.8 ± 1.5 after 12 months (homeopathic drugs included), whereas it remained stable in the UC group (baseline: 8.3 ± 5.0; 12 months: 8.5 ± 5.7). All patients in the IM group received homeopathic treatment in various potencies, mostly LM potencies. LM represents the Roman numeral for 50,000 (quinquaginta-millesimal-potency); the dilution factor is 1/50,000 instead of the customary method of 1/100 dilution (C potencies). The most frequently prescribed homeopathic drugs were Hyoscyamus niger (n = 6), Lycopodium clavatum (n = 4), opium (n = 3), and phosphorus (n = 3); a total of 27 other homeopathic drugs were also prescribed.

Due to clinically relevant group differences at baseline for age and gender, the means, 95% confidence intervals, and the effect sizes (Cohen’s d) were statistically adjusted.

After 3 and 6 months on an exploratory level, no clear differences or trends could be observed comparing outcomes of IM and UC (Table 2).

Table 2.

Outcome measures at baseline and after 3, 6, and 12 months (mean, 95% confidence intervals, Cohen’s d/effect sizes, adjusted for baseline differences)

| Outcome parameter | Results at 3 months

|

Results at 6 months

|

Results at 12 months

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IM mean (95% CI) | UC mean (95% CI) | Effect size Cohen’s d (95% CI) | IM mean (95% CI) | UC mean (95% CI) | Effect size Cohen’s d (95% CI) | IM mean (95% CI) | UC mean (95% CI) | Effect size Cohen’s d (95% CI) | |

| Activities of daily living | |||||||||

| Barthel index | 46.6 | 42.4 | 0.14 | 45.0 | 42.4 | 0.09 | 50.2 | 41.4 | 0.30 |

| (37.3; 55.9) | (37.1; 47.8) | (−0.08; 0.37) | (35.3; 54.7) | (36.8; 47.9) | (−0.15; 0.34) | (39.6; 60.8) | (35.3; 47.4) | (0.03; 0.57) | |

| AMPS motor skills | −0.3 | −0.1 | −0.12 | −0.4 | −0.1 | −0.18 | 0.1 | −0.1 | 0.12 |

| (−0.7; 0.1) | (−0.1;−0.1) | (−0.36; 0.11) | (−0.9; 0.1) | (−0.1;−0.1) | (−0.49; 0.13) | (−0.3; 0.6) | (−0.1;−0.1) | (−0.16; 0.41) | |

| AMPS process skills | −0.6 | −0.6 | 0.04 | −0.7 | −0.6 | −0.04 | −0.7 | −0.6 | −0.06 |

| (−1.0;−0.2) | (−0.8; −0.5) | (−0.21; 0.29) | (−1.1;−0.2) | (−0.8; −0.5) | (−0.37; 0.30) | (−1.2;−0.2) | (−0.8; −0.5) | (−0.49; 0.40) | |

| Cognition | |||||||||

| Mini-mental state examination | 1 1.7 | 13.4 | −0.19 | 13.2 | 13.8 | −0.06 | 15.4 | 13.9 | 0.15 |

| (9.4; 13.9) | (12.1; 14.8) | (−0.39; 0.01) | (11.2; 15.3) | (12.5; 15.0) | (−0.26; 0.14) | (12.5; 18.2) | (12.1; 15.7) | (−0.13; 0.43) | |

| Quality of life | |||||||||

| Profile of Wellbeing | 14.3 | 13.4 | 0.14 | 12.5 | 10.4 | 0.33 | 15.5 | 13.2 | 0.36 |

| (10.7; 17.9) | (10.5; 16.2) | (−0.16; 0.45) | (7.6; 17.5) | (7.0; 13.8) | (−0.23; 0.89) | (11.0; 20.0) | (9.9; 16.6) | (−0.12; 0.84) | |

| Qualidem (total sum score) | 56.6 | 54.1 | 0.14 | 51.6 | 50.1 | 0.08 | 56.0 | 49.0 | 0.39 |

| (41.5; 71.8) | (42.7; 65.6) | (−0.39; 0.67) | (36.8; 66.3) | (39.9; 60.3) | (−0.50; 0.67) | (39.1; 72.8) | (36.1; 62.0) | (−0.20; 0.98) | |

| Care relationship | 9.8 | 8.8 | 0.27 | 8.2 | 8.2 | −0.02 | 6.9 | 6.3 | 0.16 |

| (6.4; 13.2) | (6.2; 11.4) | (−0.33; 0.86) | (4.2; 12.2) | (5.4; 11.0) | (−0.80; 0.77) | (2.5; 11.3) | (2.7; 10.0) | (−0.54; 0.87) | |

| Feeling at home | 5.3 | 4.9 | 0.13 | 4.1 | 4.7 | −0.18 | 3.2 | 3.6 | −0.11 |

| (2.8; 7.8) | (3.3; 6.4) | (−0.48; 0.74) | (1.7; 6.5) | (3.2; 6.2) | (−0.80; 0.44) | (1.3; 5.1) | (2.5; 4.7) | (−0.60; 0.37) | |

| Social isolation | 3.5 | 3.3 | 0.07 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 0.15 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 0.15 |

| (1.8; 5.2) | (2.3;4.3) | (−0.57; 0.70) | (2.1; 5.2) | (2.2; 4.3) | (−0.40; 0.71) | (2.6; 5.2) | (2.5; 4.5) | (−0.34; 0.64) | |

| Positive self-image | 4.0 | 3.2 | 0.30 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 0.28 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 0.23 |

| (2.0;5.9) | (2.1;4.3) | (−0.29; 0.89) | (1.7; 4.8) | (1.5; 3.6) | (−0.22; 0.79) | (2.0; 4.9) | (1.9; 3.8) | (−0.25; 0.71) | |

| Restless tense behavior | 1.3 | 2.3 | −0.51 | 2.6 | 2.7 | −0.05 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 0.24 |

| (0.2; 2.4) | (1.6; 3.0) | (−0.96; −0.06) | (1.3; 3.9) | (1.8; 3.6) | (−0.61; 0.52) | (0.8; 3.6) | (0.8; 2.6) | (−0.41; 0.90) | |

| Having something to do | 2.6 | 2.2 | 0.18 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 0.08 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 0.35 |

| (1.7; 3.5) | (1.8; 2.7) | (−0.18; 0.54) | (1.3; 3.4) | (1.7; 2.7) | (−0.38; 0.54) | (1.6; 3.8) | (1.4; 2.5) | (−0.15; 0.86) | |

| Negative affect | 3.0 | 2.8 | 0.08 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 0.17 | 4.9 | 4.2 | 0.33 |

| (1.6; 4.4) | (1.9; 3.8) | (−0.30; 0.46) | (2.1; 5.0) | (2.2; 4.1) | (−0.26; 0.60) | (3.3; 6.6) | (3.1; 5.3) | (−0.16; 0.82) | |

| Positive affect | 10.1 | 10.8 | 0.03 | 9.9 | 9.0 | 0.21 | 10.3 | 8.7 | 0.37 |

| (8.3; 13.4) | (8.7; 12.8) | (−0.31; 0.36) | (6.1; 13.7) | (6.1; 11.9) | (−0.38; 0.80) | (5.9; 14.6) | (5.4; 12.0) | (−0.31; 1.05) | |

| Social relation | 8.0 | 7.4 | 0.17 | 8.4 | 8.0 | 0.10 | 8.3 | 6.4 | 0.49 |

| (5.4; 10.7) | (5.4; 9.4) | (−0.22; 0.57) | (5.5; 11.3) | (6.2; 9.8) | (−0.48; 0.68) | (5.1; 11.4) | (4.3; 8.6) | (−0.07; 1.05) | |

| Multidimensional NOSGER | |||||||||

| Depressed mood | 4.8 | 5.4 | 0.17 | 5.2 | 6.3 | 0.31 | 4.1 | 5.4 | 0.40 |

| (2.7; 7.0) | (3.5; 7.3) | (−0.22; 0.55) | (3.2; 7.3) | (4.5; 8.0) | (−0.09; 0.70) | (1.9; 6.2) | (3.8; 7.1) | (−0.08; 0.89) | |

| Impaired activities of daily living | 9.1 | 10.6 | 0.31 | 9.7 | 11.6 | 0.41 | 8.3 | 10.8 | 0.53 |

| (6.0; 12.2) | (8.1; 13.1) | (−0.25; 0.88) | (7.0; 12.3) | (8.9; 14.3) | (0.02; 0.80) | (5.7; 10.9) | (8.3; 13.4) | (0.09; 0.97) | |

| Impaired memory | 11.7 | 12.5 | 0.18 | 9.6 | 11.4 | 0.40 | 11.3 | 11.6 | 0.08 |

| (8.1; 15.3) | (9.0; 16.0) | (−0.33; 0.69) | (5.9; 13.3) | (8.2; 14.6) | (−0.08; 0.88) | (6.7; 15.9) | (7.9; 15.4) | (−0.51 ; 0.66) | |

| Impaired social behavior | 8.9 | 10.1 | 0.21 | 8.4 | 9.8 | 0.25 | 8.8 | 11.4 | 0.47 |

| (5.5; 12.4) | (7.2; 13.0) | (−0.25; 0.67) | (4.9; 11.9) | (6.8; 12.7) | (−0.24; 0.74) | (5.2; 12.5) | (8.6; 14.3) | (−0.08; 1.03) | |

| Disturbing behavior | 5.3 | 6.5 | 0.36 | 4.7 | 5.3 | 0.20 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 0.03 |

| (2.2; 8.5) | (4.6; 8.4) | (−0.36; 1.07) | (1.7; 7.6) | (3.4; 7.3) | (−0.41; 0.82) | (1.1; 6.6) | (2.1; 5.7) | (−0.59; 0.64) | |

| Impaired instrumental activities of daily living | 14.7 | 14.5 | −0.03 | 13.7 | 14.1 | 0.09 | 18.3 | 19.1 | 0.18 |

| (11.0; 18.4) | (11.0; 18.0) | (−0.43; 0.37) | (10.1; 17.3) | (10.6; 17.5) | (−0.30; 0.49) | (14.2; 22.4) | (15.4; 22.8) | (−0.36; 0.72) | |

| Risk of falls | |||||||||

| Tinetti score | 11.1 | 11.0 | 0.01 | 10.4 | 11.0 | −0.07 | 11.0 | 10.7 | 0.04 |

| (8.7; 13.5) | (9.7; 12.3) | (−0.21; 0.23) | (7.7; 13.1) | (9.5; 12.4) | (−0.35; 0.20) | (7.8; 14.2) | (9.0; 12.4) | (−0.29; 0.37) | |

Abbreviations: AMPS, assessment of motor and process skills; CI, confidence interval; IM, Integrative Medicine; NOSGER, nurses observation scale for geriatric patients; UC, usual care.

After 12 months, improvements with medium effect sizes ≥0.3 were noted in ADL, Quality of Life, Wellbeing, and specific affective and social functioning outcomes (see Table 2). This included BI (0.30 [0.03; 0.57]), Profile of Wellbeing (0.36 [−0.12; 0.84]), Qualidem total sum (0.39 [−0.20; 0.98]), Qualidem-having something to do (0.35 [−0.15; 0.86]), Qualidem-negative affect (0.33 [−0.16; 0.82]), Qualidem-positive affect (0.37 [−0.31; 1.05]), Qualidem-social relation (0.49 [−0.07; 1.05]), NOSGER-depressed mood (0.40 [−0.08; 0.89]), NOSGER-impaired ADL (0.53 [0.09; 0.97]), and NOSGER-impaired social behavior (0.47 [−0.08; 1.03]). There was a higher risk for falls in the IM than in the UC (odds ratio 3.30; 95% confidence interval: 0.43; 25.26), but hospital admissions were in general comparable for both groups (IM: 0.7 ± 1.1; UC 1.0 ± 1.8).

We observed seven deaths in the IM group caused by cardiovascular disease (three patients), cancer (three patients), and age (one patient, 102 years of age); three deaths in the UC group were caused by cardiovascular disease.

The study physicians discussed the feasibility of the trial every 3 months. Overall, they judged the intervention itself as feasible but found it elaborate and time consuming. The amount of adherence and identification with this study differed between the caregivers; generally, it seemed the female caregivers identified themselves very much with the study and observed good clinical results, whereas male caregivers were much more skeptical and supported the interventions to a lesser degree.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first time that an additional complex IM program consisting of lifestyle change, naturopathic care, and homeopathic drug therapy was developed applied and evaluated in older adults in apartment-sharing communities. Exploratory effect sizes of ≥0.3 in favor for the IM intervention were observed after 12 months for ADL, Wellbeing, and Quality of Life.

Strengths of this study are the pragmatic and naturalistic approach, and the relatively large sample for a pilot study. The intervention was added to a naturalistic setting; we intended to include all patients living in the apartments to avoid selection. It is important to understand that the intervention was not designed to evaluate specific effects of homeopathic drugs, but to test a holistic geriatric treatment approach that included homeopathic treatment philosophy with lifestyle change.9 As this was a complex intervention consisting of several treatment modules, it is not possible to relate effects to single parts of the intervention (eg, exercise, reduction of conventional medication, naturopathic care, homeopathic treatment, or additional care offerings in general).

We chose a clustered randomization because it reflected best the typical setting for this complex intervention. It would not have been possible to provide lifestyle changes to only half of the patients in an apartment. However, cluster-randomized trials have drawbacks; it turned out that the clustered randomization resulted in group differences at baseline regarding age and gender. Therefore, we had to adjust in our exploratory data analyses for these baseline differences. By doing so and performing multiple imputations for missing values, we tried to provide more solid data while avoiding a confirmatory statement.

This was a study on older patients, who generally have a higher risk of passing away during the treatment or follow-up period. Moreover, this risk is considerably higher in more seriously ill patients. Consequently, we imputed missing values to have a more realistic result by including estimated values for the more seriously ill patients.

Although this study was a cluster-randomized trial, the number of clusters and patients was small. This generally bears the risk of group imbalances, and indeed it turned out that the groups differed in age and gender. We therefore decided to adjust our statistical analyses for these parameters. However, results with and without adjustments did not differ relevantly, although the group differences were generally somewhat smaller in unadjusted models (eg, standard mean difference of 0.14 versus 0.12 in the BI after 3 months). In general, we believe that adjusted models are more trustworthy, because they do have a lower risk of bias.

In the IM group, the mean age was 83 years, compared to 76 years in the UC group. The state of health for the whole IM sample might therefore have been more unstable compared to the UC sample. This hypothesis is supported by the group differences at baseline. More IM patients (24%) were receiving the highest level of care, compared to 10% of the control group. Systematic analyses of surveys of the elderly US population showed consistency of declines in any disability (−1.55% to −0.92% per year), instrumental activities of daily living disability (−2.74% to −0.40% per year), functional limitations, and limited evidence on cognition and conflicting evidence on self-reported ADL (changes ranged from −1.38% to 1.53% per year).19 Differences in age between the groups may also explain the higher rate of death and higher incidence of falls in the IM group. For future confirmatory trials, it should be estimated that approximately 20 percent of the study population may die naturally within a 12-month study period.

More falls were observed in the IM group. This could be explained solely by the age differences between the groups. But the fact that patients exercised could have contributed to this observation, although falls did not happen while patients were exercising. Nevertheless, falls would not have happened in patients without motivating caregivers to start walking with them again. This is an ethical dilemma: mobilizing patients is considered to be beneficial, and exercise training might increase autonomy and abilities of daily functioning in the elderly, but falls due to walking may have fatal consequences.

Generally, the adherence to the sports program was very high, as the training was implemented as a regular weekly group activity and was supervised by sports therapists recruited especially for this study. The adherence to nutritional changes and naturopathic therapies by the caregivers was substantially lower, and varied from apartment to apartment depending on the motivation of the caregivers. It turned out that it was not possible to practically measure these daily activities closely because caregivers and cooks could not be motivated to keep extra documentation on these activities.

The results of this trial indicate that such a complex treatment program might help older adults to improve ADL and Quality of Life as well as affective and social functioning. We consider the differences of the adjusted means of the BI and the NOSGER-impaired activities of daily living both after 12 months as clinically relevant group differences, justifying a larger trial with confirmatory design. However, it has to be emphasized that no relevant improvements were found after 3 or 6 months. If the improvements were due to the interventions, an effect can only be expected after a longer intervention time.

For a full-scale clinical trial, the following aspects should be considered: Activities of Daily Living (eg, BI or NOSGER) and Quality of Life after 12 months or even longer might represent the most promising outcomes for studies, including patients with different diseases in this age group. Reducing the outcome assessment to only a few assessments would also save resources. Focusing only on patients with a specific disease would reduce variance and sample size, and allow for a more disease-specific outcome, but it would introduce a more artifcial setting because in apartment-sharing communities patients usually suffer from multiple and varying diseases. The study physicians subjectively had the clinical impression that the observed clinical effects were higher than shown in the results of the quantitative analyses. This impression was also supported by the observation of the caregivers responsible for the patients in the IM group.

Study physicians observed that the effects were higher in apartments where the caregivers identified with the IM program and actively supported the study. Both study physicians gave the opinion that for further projects, a high identification with IM and good clinical training of caregivers might be essential for obtaining good clinical results.

Conclusion

This exploratory pilot study showed that for a full-scale trial, the outcomes of ADL and Quality of Life seem to be the most promising. Although the IM program was feasible, it was elaborate and time consuming.

Acknowledgments

We thank Homöopathie-Stiftung, omoeon e.V., and Karl and Veronica Carstens-Stiftung for funding, and Reck-Technik GmbH for supporting our trial with Motomed ergometer devices. We thank patients, legal guardians, and Pollex Pflegedienst (Berlin) for participating in this study, and our study nurses Beatrice Eden and Katja Icke for trial management and data management.

Author contributions

Study concept and design: MT, CMW, KS. Organization and data management: MT, KS. Design of intervention: MT, FR, N P, FB, AK. Study physicians: MT, RB. Exercise training: FR, N P, FB. Training of caregivers: AK. Geriatric assessments: KS. Statistical analysis: RL. Analysis and interpretation of data: MT, RL, CMW, KS. Obtained funding: MT, CMW. All authors drafted or revised, commented on, and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Weyerer S.Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes: Altersdemenz [Reporting of federal health: dementia] 200528Robert Koch Institut; Berlin: Available from: https://www.gbe-bund.de/Accessed March 15, 2012German [Google Scholar]

- 2.Statistisches Bundesamt . Bevölkerung Deutschlands bis 2050. 10. koordinierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung [Federal Statistical Office (2003): Germany’s population by 2050. 10th coordinated population forecast] Statistisches Bundesamt; Wiesbaden: 2003. German. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schaeffer D, Buscher A. Options for health care promotion in long-term care: empirical evidence and conceptual approaches. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;42(6):441–451. doi: 10.1007/s00391-009-0071-3. German [with English abstract] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Institut für Demoskopie Allensbach Naturheilmittel 2010 – Ergebnisse einer bevölkerungsrepräsentativen Befragung [Natural Remedies 2010 – results of a representative population survey; webpage on the Internet] Available from: http://www.ifd-allensbach.de/uploads/tx_studies/7528_Naturheilmittel_2010.pdfAccessed January 20, 2013German

- 5.Cheung CK, Wyman JF, Halcon LL. Use of complementary and alternative therapies in community-dwelling older adults. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13(9):997–1006. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ness J, Cirillo DJ, Weir DR, Nisly NL, Wallace RB. Use of complementary medicine in older Americans: results from the Health and Retirement Study. Gerontologist. 2005;45(4):516–524. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.4.516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer M, Rayner JA. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in residential aged care. J Altern Complement Med. 2012;18(11):989–993. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmberg C, Brinkhaus B, Witt C. Experts’ opinions on terminology for complementary and integrative medicine – a qualitative study with leading experts. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12:218. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-12-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Teut M, Dahler J, Lucae C, Koch U. Kursbuch Homöopathie [Course book Homeopathy] München: Elsevier Publishers; 2008. German. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hahnemann S, Schmidt JM. Organon der Heilkunst. Neufassung der 6. Auflage mit Systematik und Glossar (2. Aufl.) [Organon of Medicine. Recasting of the 6. Edition with systematics and glossary (2nd edition)] München: Elsevier/Urban and Fischer; 2006. German. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wahle M, Haller S, Spiegel R. Validation of the NOSGER (Nurses’ Observation Scale for Geriatric Patients): reliability and validity of a caregiver rating instrument. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8(4):525–547. doi: 10.1017/s1041610296002864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kottorp A, Bernspång B, Fisher AG. Validity of a performance assessment of activities of daily living for people with developmental disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2003;47(Pt 8):597–605. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gantschnig BE, Page J, Fisher AG. Cross-regional validity of the assessment of motor and process skills for use in middle Europe. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44(2):151–157. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouman AI, Ettema TP, Wetzels RB, van Beek AP, de Lange J, Droes RM. Evaluation of Qualidem: a dementia-specific quality of life instrument for persons with dementia in residential settings; scalability and reliability of subscales in four Dutch field surveys. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26(7):711–722. doi: 10.1002/gps.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Riesner C, Müller-Hergl C, Mittag M. Wie geht es Ihnen? Konzepte und Materialien zur Einschätzung des Wohlbefindens von Menschen mit Demenz [How are you? Concepts and materials for assessing the well-being of people with dementia] Vol. 3. Demenz-Service; 2005. German. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tinetti ME. Performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34(2):119–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1986.tb05480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freedman VA, Martin LG, Schoeni RF. Recent trends in disability and functioning among older adults in the United States: a systematic review. JAMA. 288(24):3137–3146. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.24.3137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]