Abstract

Background

Tourism areas represent ecologies of heightened HIV vulnerability characterized by a disproportionate concentration of alcohol venues. Limited research has explored how alcohol venues facilitate HIV transmission.

Methods

We spatially mapped locations of alcohol venues in a Dominican tourism town and conducted a venue-based survey of key informants (n=135) focused on three facets of alcohol venues: structural features, type of patrons, and HIV risk behaviors. Using latent class analysis, we identified evidence-based typologies of alcohol venues for each of the three facets. Focused contrasts identified the co-occurrence of classes of structural features, classes of types of patrons, and classes of HIV risk behavior, thus elaborating the nature of high risk venues.

Results

We identified three categories of venue structural features, three for venue patrons, and five for HIV risk behaviors. Analysis revealed that alcohol venues with the greatest structural risks (e.g., sex work on site with lack of HIV prevention services) were most likely frequented by the venue patron category characterized by high population-mixing between locals and foreign tourists, who were in turn most likely to engage in the riskiest behaviors.

Conclusion

Our results highlight the stratification of venue patrons into groups who engage in behaviors of varying risk in structural settings that vary in risk. The convergence of high-risk patron groups in alcohol venues with the greatest structural risk suggests these locations have potential for HIV transmission. Policymakers and prevention scientists can use these methods and data to target HIV prevention resources to identified priority areas.

Keywords: Alcohol venues, HIV transmission, Tourism, Dominican Republic, Latent cluster analysis

1. INTRODUCTION

Alcohol consumption and availability have increasingly been implicated as factors associated with HIV transmission (Bryant, 2006). Dominant models examining the association between alcohol use and HIV transmission have largely focused on individual difference variables (George and Stoner, 2000; Cook and Clark, 2005). This literature posits that alcohol elevates HIV vulnerability though multiple mechanisms related to decision-making, including dampening protective cues (Steele and Josephs, 1990), altering perceived expectations regarding alcohol use-related sexual expectancies (Cooper, 2002), and reducing sexual inhibitions (George and Stoner, 2000; Kalichman and Cain, 2004), thus facilitating the likelihood of risky sexual behavior. Alcohol may also increase individual susceptibility to HIV by disrupting immune system functioning, which can impair the body’s defenses to HIV infection (Pandrea et al., 2010; Hahn et al., 2011) and lead to more rapid development of the disease in HIV positive individuals (Hahn and Samet, 2010). Despite recognition that alcohol is a significant contributor to HIV risk, it has been relatively overlooked in current HIV prevention efforts (Fritz et al., 2010). The few alcohol-based HIV prevention interventions have largely focused on altering alcohol use by appealing to individual-level variables (O’Leary et al., 2003; Kalichman, 2010). Overall, these studies have yielded mixed, short-term effects (Kalichman et al., 2007, 2008; Kalichman, 2010), suggesting the need to consider the social dynamics and structural context of alcohol environments.

Emerging research emphasizes alcohol venues as potential targets for HIV prevention efforts (Lewis et al., 2005; Kalichman, 2010). Research in South Africa (Morojele et al., 2006; Kalichman et al., 2008), India (Go et al., 2007; Sivaram et al., 2008) and Zimbabwe (Fritz et al., 2002; Mataure et al., 2002; Lewis et al., 2005) highlight the role of alcohol consumption on individual HIV risk behavior, and how venues shape HIV risk. Extant research reports likelihood of HIV risk behaviors in alcohol settings (Fritz et al., 2002; Go et al., 2007; Kalichman et al., 2008), and in some instances has documented an increased prevalence of HIV among venue patrons compared with the general population (Lewis et al., 2005; Go et al., 2007). Findings highlight that risky sexual behavior is often facilitated by the structural environment of alcohol venues, such as the availability of on-site locations for transactional sex, as well as sexually suggestive entertainment (Morojele et al., 2006; Kalichman et al., 2008; Ao et al., 2011). Research suggests three main venue-related factors that contribute to HIV risk: the structural environment of venues, risk groups that frequent venues and risky interactions that occur between risk groups at venues. Although previous studies have documented the presence or absence of one or more of the above HIV risk indicators in alcohol venues, we know of no study that has assessed the convergence of these factors to identify areas where risk of HIV transmission is increased. Greater understanding of how spatial, social, and behavioral dynamics in alcohol venues shape individual HIV risk can guide intervention development as to how to best target venues for HIV prevention.

The present study addressed this gap by examining the structural features, patrons, and HIV risk behaviors of alcohol venues situated in a Caribbean tourism area of the Dominican Republic (D.R.). The Caribbean has the highest regional HIV/AIDS prevalence outside of Sub-Saharan Africa, (0.9% – 1.1%), and is well known for its availability and consumption of alcohol (Padilla et al., 2010; UNAIDS, 2010; Padilla et al., 2012). This study sought to characterize the risk typology of alcohol venues in a tourism town of the D.R. which, together with Haiti, accounts for 70% of the disease burden in the region and has a country HIV prevalence of 0.7% (0.6% – 0.8%) (UNAIDS, 2011). Important to note is variability in country-level HIV prevalence by region, with areas with greater tourism development tending to be more heavily impacted by HIV (CESDEM, 2003). Given that the D.R. received more tourists than any other Caribbean country in 2011 (4.3 million) and with the projected number of international tourist arrivals worldwide is estimated to total 1 billion in the year of 2012 (Caribbean Tourism Organization, 2011; United Nations World Tourism Organization, 2012), a better understanding of how contexts of alcohol use shape HIV risk in tourism areas is of global importance.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data Collection Procedures

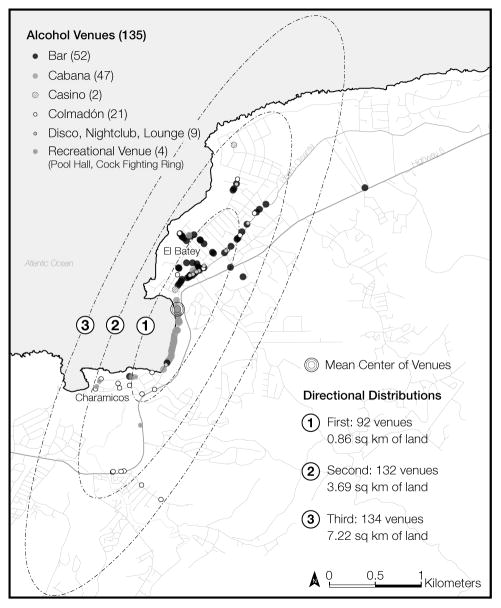

We used a two-phase ethnographic framework, which combines spatial analysis and venue-based surveys to assess the structural features, clientele, and behavioral characteristics of alcohol venues in the tourism town of Sosúa, D.R. (Oliver-Velez, 2002). Sosúa is a small town of 45,000 located on the D.R.’s North Coast in the province of Puerto Plata which, in recent years, has become internationally known for sex tourism (Padilla, 2007; Brennan, 2004). The first phase of ethnographic mapping involved using an official reference map to document the locations of all alcohol-serving venues in Sosúa. We identified 135 alcohol-serving venues such as bars (38.5%), cabanas (e.g., beach bars; 34.8%), “colmadones” (e.g., stores where liquor could be purchased and consumed on site; 15.6%), discos/nightclubs/ lounges (6.7%), recreational venues (e.g., pool halls or cockfighting rings; 3.0%), and casinos (1.5%). Venues were included if alcohol could be purchased, consumed on-site, and there were opportunities for HIV risk behavior to occur (i.e., patrons remained on-site to interact socially and/or engage in transactional exchanges). Each venue was verified and mapped using ESRI’s ArcGIS software, revealing a high concentration of alcohol venues within a small geographic area (Figure 1). Specifically, spatial analysis using standard deviational ellipses around the mean center of venues in Sosúa demonstrated that the majority (68%) of venues are contained within 0.86 square kilometers of the first deviational ellipse, which maps onto the town’s main tourism district known as El Batey. Nearly all (98%) of venues are contained within 3.69 square kilometers of the second deviational ellipse which also includes the adjacent local Dominican community of Charamicos.

Figure 1.

Map of Alcohol Venues in Sosúa, Dominican Republic.

In the second phase, the Investigative Team visited venues and conducted a minimum of one hour of observation in each venue to identify a key informant. The informant was someone employed at the venue, knowledgeable about venue characteristics due to longer-term employment or a supervisory role, and was willing to speak with project staff. The informant then completed a survey related to venue structural features, patrons, and behaviors. No subjects refused participation as key informants.

2.2. Measures

Measures included whether the venue was a location for formal or informal sex work, had on-site private rooms or outside-venue private areas, offered free drinks or drink specials, or offered HIV prevention services (i.e., condoms available for free or purchase, lubrication available for free or purchase, or health check-ups for employees; MEASURE Evaluation, 2005). Measures of patron characteristics assessed clientele country of origin, including if patrons were local Dominicans, local Haitians, Dominican tourists, or foreign tourists. Finally, measures of venue behaviors included types of observed patron behaviors, including people who drink a lot, and people who engage in sex or drug-related transactions such as: women who have sex for money (female sex workers), women who have sex with women (lesbian), men who have sex with men (gay), men who have sex with female tourists for money (“sanky pankies”), men who have sex with men for money (bugarrones), and transgender/transsexuals. Informant responses were supplemented by direct observation by interviewers in the venue. Due to the ability of the research team to verify objective characteristics of the venues, the levels of agreement were exceptionally high (greater than 90%), suggesting high reliability.

Each measure was dichotomous, scored 1 = present, 0 = not present. Informed consent from informants was obtained and participants were offered 350 pesos, approximately $10 U.S. dollars. Institutional approval from Columbia University and Universidad Autónoma de Santo Domingo was obtained prior to the study.

2.3. Data Analysis

We used latent class analysis (LCA) to cluster the venues into meaningful categories. LCA posits an unobserved (latent) categorical variable that accounts for the manifest relationships among the observed venue-based variables (DiStefano and Kamphaus, 2006; Jiang and Zack, 2011). It classifies venues into the latent variable categories to best account for the interrelationships among the measured venue characteristics and estimates a probability that each venue belongs to each latent class. A venue is assigned to the class/cluster that it has the highest probability of being in (DiStefano and Kamphaus, 2006). Quality solutions yield a high probability of any given venue being in one of the categories, coupled with low probabilities of being in the other categories. LCA estimates the number of clusters or categories needed to best account for the data by systematically comparing likelihood functions for multiple models with different numbers of clusters and selecting the model that yields the best, conceptually meaningful fit (DiStefano and Kamphaus, 2006).

Three separate LCAs were performed. The first LCA focused on structural features of the venue that might impact HIV infection, i.e., venue-structural features. The second LCA focused on the type of patron who uses the venue as defined by their region of origin, i.e., venue patrons. The third LCA analyzed specific risk behaviors that occur within the venue, i.e., venue-based risk behavior. The number of categories for a given LCA was determined by testing models ranging from 2 to 8 classes and then selecting the model that (1) had the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) value, (2) yielded a statistically significant improved fit from a model with one fewer categories as indexed by a bootstrapped Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR) test, (3) showed a non-trivial log likelihood improvement to models with lesser categories but not so for models with more categories, and (4) made conceptual sense. Once a model was selected, we evaluated the mean classification probabilities across venues as a function of the latent category to which venues were assigned to ensure that classification was unambiguous.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Latent Class Analyses

The details of the model fitting process for the three LCAs are presented in Supplementary Table 11. The LCA for venue structural features yielded a three category solution; for the venue patrons, a three category solution also was best, and for the venue risk behaviors, a five cluster solution was best. Table 1 presents the relevant information for each LCA. We discuss each in turn.

Table 1.

Conditional Probabilities of Venue Characteristics in Latent Classes

| Venue Features | Safer Venues | Risky Venues | Equipped Venues |

|---|---|---|---|

| LC Size | 45.8% | 37.4% | 16.8% |

| Formal Sex Work | .000 | .139 | .477 |

| Informal Sex Work | .000 | .942 | .817 |

| Patrons Looking for Sex | .097 | .086 | .747 |

| Private Rooms | .173 | .000 | .226 |

| Outside-Venue Private Areas | .145 | .911 | .000 |

| Free Drinks | .108 | .274 | .122 |

| Other Drink Specials | .137 | .197 | .153 |

| Condoms for Purchase | .261 | .000 | .700 |

| Health Check-ups | .155 | .023 | .700 |

| Free Condoms on Site | .000 | .000 | .000 |

| Condom Machine on Site | .000 | .000 | .000 |

| Lubrication on Site | .000 | .000 | .000 |

| Free Lubrication on Site | .000 | .000 | .000 |

|

| |||

| Venue Patrons | Locals/Haitians | Foreign Tourists | All Groups |

| LC Size | 12.2% | 34.4% | 53.4% |

|

| |||

| Local Dominicans | 1.00 | 0.431 | 1.00 |

| Foreign Tourists | .000 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Dominican Tourists | .187 | .245 | .938 |

| Haitians | .813 | .303 | .986 |

| People who Come to Meet Tourists | .000 | .446 | .871 |

| Venue-Based Behaviors | Drinking | Same-Sex Behavior | Hetero-Sex Trade | Drinking and Sex | All HIV Risk Behaviors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC Size | 29.8% | 4.6% | 20.6% | 22.9% | 22.1% |

| Female Sex Worker | .030 | .000 | .923 | .934 | .961 |

| Sanky | .000 | .000 | .930 | .998 | 1.00 |

| Bugarrone | .260 | .000 | .701 | .966 | 1.00 |

| Gay Male | .024 | 1.00 | .070 | .997 | 1.00 |

| Lesbian | .000 | .828 | .078 | .995 | .975 |

| Transsexual | .000 | .497 | .039 | .811 | 1.00 |

| People Who Sell Drugs | .510 | .000 | .000 | .059 | .635 |

| People Who Buy Drugs | .102 | .166 | .151 | .091 | .939 |

| People Who Drink A Lot | .745 | .834 | .924 | .999 | 1.00 |

| People Who Buy Sex | .087 | .458 | .744 | .769 | .903 |

Note: Entries refer to the proportion of venues within the category that had the attribute or characteristic listed in the row. LC size is the percentage of the 135 venues that were classified into the indicated cluster.

3.1.1. Venue-Structural Features

The three venue clusters in this typology were labeled as “safer”, “risky” and “equipped” venues. The “safer venue” cluster was characterized by the absence of sex work and some HIV prevention services, such as condoms for purchase and health check-ups. Nearly half (46%) of the 135 venues were of this character. “Risky venues” were the second most prevalent type of venue, accounting for 37% of venues. Risky venues were likely to have sex work that was facilitated by the availability of private outside areas, which may provide patrons with spaces to engage in commercial or transactional sex. Risky venues were unlikely to have HIV prevention services. “Equipped venues” were the most rare structural venue profile, accounting for 17% of venues. This cluster had a high degree of both formal and informal sex work but also tended to have HIV prevention services available. Important to note is that the venue based survey also collected data on potential structural features of venues with HIV prevention implications: free condoms on site, condom machine on site, lubrication on site, and free lubrication on site. However, none of the venues had these features (hence they were excluded from the LCA). These results indicate that the types of condoms in venues were available for purchase via request and that lubrication was not available.

3.1.2. Venue Patrons

The three categories for venue patrons were described as (1) local Dominicans and Haitians, (2) foreign tourists, and (3) all groups. Venues that service primarily local Dominicans and Haitians were the least common type of patron cluster (12%), suggesting that alcohol venues primarily target tourists. The second largest patron cluster (34%) was predominately comprised of foreign tourists and to a lesser degree, patrons seeking to meet tourists, and local Dominicans and Haitians. Most alcohol venues (53%) were likely to be frequented by all patron groups in equal proportion, suggesting a high degree of population mixing.

3.1.3. Venue-Based Risk Behaviors

The five clusters in this LCA were broadly characterized as (1) drinking, (2) same-sex behavior, (3) heterosexual sex-trade, (4) drinking and sex, and (5) all HIV risk behaviors. The largest number of venues (30%) were those where the predominant risk behavior was heavy drinking. Venues with heterosexual and same-sex transactions combined with heavy drinking were the second most observed behavioral pattern (23%). Venues that were characterized by all HIV risk behaviors represented less than one-quarter (22%) of venues. The behavioral cluster “heterosexual sex trade,” noted by the presence of female sex workers, sankies, and bugarrones, and which co-occurs with a high frequency of heavy drinking, occur in approximately one-fifth (21%) of all venues. Finally, the least common behavioral class of venue was same-sex behavior (5%), characterized as having high probabilities of lesbian, gay, and transsexual patrons as well as people looking to buy sex, suggesting both non-transactional and transactional same-sex exchanges.

3.2. Relationships among Venue Types

We next conducted analyses to determine if there was a relationship between the type of structural features that venues have (as defined by the three clusters for structural features), the kinds of patrons who frequent venues (as defined by the three patron clusters), and the kinds of risk behaviors that occur in the venues (as defined by the five risk behavior clusters). The sample size was too small to approach this matter with more sophisticated multivariate modeling, so exploratory contingency table analyses were pursued. These analyses used exact (as opposed to asymptotic) chi square tests coupled with targeted contrasts of pairs of independent proportions using the Bayesian method described by Agresti and Caffo (2000). We describe three sets of results below: (1) the extent to which venues with different structural features were likely to be frequented by different types of patrons, (2) the extent to which different risk behavior patterns were likely to be on-going in venues with different structural features, and (3) the extent to which different types of patron clusters were likely to be engaging in different behavioral patterns in terms of risk behavior.

3.2.1. Are Venues that Vary in Structural Features Likely to be Frequented by Different Patron Clusters?

We observed a statistically significant omnibus test for alcohol venues clustered by structural features crossed with clusters of venue patrons (chi square = 58.1, df =4, p<0.05, Cramer’s V = 0.47; Table 2). Notably, risky sex venues characterized by high informal and formal sex work but which lack HIV prevention services were most likely to be frequented by all groups together (0.94) compared to equipped venues (0.41) and safer venues (0.26). Equipped sex venues were most likely to be frequented by foreign tourists (0.55), compared to risky venues (0.06), and safer venues (0.50). Finally, safer venues were more likely to have local Dominican and Haitians patrons (0.25) than equipped (0.05) or risky venues (0.00). These results suggest that risky sex venues have elevated risk given they are locations for population mixing. Safer venues, in contrast, are low on population mixing, further underscoring their low risk. Tourists were likely to be at risky venues as part of the mixed patron class, or at equipped venues where sex is for sale, but some protective measures are in place. Together, these results suggest the risk context in which tourists are embedded depends on patron groups with whom they interact.

Table 2.

Conditional Probabilities for Venue Patrons as a Function of Venue Structural Features

| Latent Class | Safer Venues (46%) | Risky Venues (37%) | Equipped Venues (17%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Locals/Haitians (12%) | .250 | .000 | .045 |

| Foreign Tourists (34%) | .500 | .061 | .545 |

| All Groups (53%) | .259 | .939 | .409 |

Note: Percentages in parentheses are cluster size, i.e., the percentage of the 135 venues that occur in the listed category. Cell entries are estimated conditional probabilities for the row variable conditioned on the column variable (e.g., the probability of patrons in the Locals/Haitians cluster frequenting a venue given that it is in the Safer Venus cluster is 0.25; or, stated alternatively, of those patrons who frequent Safer Venues, 25% of them fall into the cluster Locals/Haitians).

3.2.2. Do the Types of Behavioral Patterns On-Going in Venues Differ by Venue Structural Features?

We observed a statistically significant omnibus test for alcohol venues clustered by structural features and risk-associated behavioral patterns (chi square = 54.8, df = 8, p<0.05; Cramer’s V = 0.46; Table 3). Safer venues were most likely to be characterized by a pattern of heavy drinking alone (0.58), compared to equipped (0.18) and risky sex venues (0.00). These data suggest patrons frequent safe venues solely to consume alcohol. Alcohol venues with the most risky behavior typology, either all HIV risk behaviors (i.e. drinking, heterosexual and same sex transactions, and drug transactions) or drinking and sex transactions without drug transactions, were both most likely to occur in risky sex venues (0.37, respectively). These HIV risk behavior typologies were to a lesser extent equally likely to occur in equipped sex venues (0.23, respectively), followed by safer venues (0.10, 0.12). Equipped and risky sex venues were more likely to have heterosexual sex trade exchanges (0.27, respectively) compared to same-sex trade exchanges (0.09 vs. 0.00).

Table 3.

Conditional Probabilities for Venue-Based Risk Behaviors as a Function of Venue Structural Features

| Latent Class | Safer Venues (46%) | Risky Venues (37%) | Equipped Venues (17%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Drinking (30%) | .583 | .000 | .182 |

| Same-Sex Behavior (5%) | .067 | .000 | .091 |

| Heterosexual Sex Trade (21%) | .133 | .265 | .273 |

| Drinking and Sex (23%) | .117 | .367 | .227 |

| All HIV Risk Behaviors (22%) | .100 | .367 | .227 |

Note: Percentages in parentheses are cluster size, i.e., the percentage of the 135 venues that occur in the listed category. Cell entries are estimated conditional probabilities for the row variable conditioned on the column variable (e.g., the probability of a behavioral pattern of just heavy drinking given a Safer Venue is 0.583; or, stated alternatively, of the Safer Venues, 58.3% of them are characterized by primarily heavy drinking).

3.2.3. Do the Types of Behavioral Patterns On-going in Venues differ by Patron Cluster?

Finally, we observed a statistically significant omnibus test for a contingency table defined by the types of patrons who attend Sosúa alcohol venues and behavioral patterns associated with those venues (chi square=52.48, df =8, p<0.05; Cramer’s V=0.46; Table 4). Locals were more likely to attend venues characterized by heaving drinking (0.69) as compared to foreign tourists (0.51) or all groups together (0.07). The patron cluster of all groups together was most likely to fall in the behavioral cluster of engaging in all risk HIV behaviors (0.37), drinking and sex transactions (0.31), and heterosexual sex trade (0.21) as compared to either foreign tourists or locals alone. These data highlight that patrons mixing with all other types of clientele engage in the riskiest behaviors. Interesting to note is that foreign tourists were most likely to engage in same sex behaviors compared to all groups and locals (0.09 vs. 0.03 and 0.00, respectively).

Table 4.

Conditional Probabilities for Venue Behaviors as a Function of Venue Patrons

| Latent Class | Locals/Haitians (12%) | Foreign Tourists (34%) | All Groups (53%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Drinking (30%) | .686 | .511 | .071 |

| Same-Sex Behavior (5%) | .000 | .089 | .029 |

| Heterosexual Sex Trade (21%) | .188 | .200 | .214 |

| Drinking and Sex (23%) | .000 | .178 | .314 |

| All HIV Risk Behaviors (22%) | .125 | .022 | .371 |

Note: Percentages in parentheses are cluster size, i.e., the percentage of the 135 venues that occur in the listed category. Cell entries are estimated conditional probabilities for the row variable conditioned on the column variable (e.g., the probability of a behavioral pattern of just heavy drinking given one is in the patron cluster of Locals/Haitians is 0.686; or, stated alternatively, of those patrons who are in the “Locals/Haitians” cluster, 68.6% of them go to venues that have behavioral patterns characterized primarily by heavy drinking).

4. DISCUSSION

Our primary objective was to describe naturally occurring clusters of alcohol venues on three dimensions that have implications for the design of HIV prevention programs: venue-based structural features associated with HIV, the types of patrons who visit alcohol venues, and risk behavioral patterns that occur in alcohol venues. Our results suggest alcohol venues are a connecting point where patrons consume alcohol, seek sexual encounters and/or drug transactions, and interact with diverse populations. Our analysis reveals a convergence of the most risky typology of each class of venue characteristic. The most high risk venues by structural feature typology, characterized by high formal and informal sex work and lack of HIV prevention services, are almost exclusively locations where all categories of patrons meet in roughly equal proportion. This “mixer class” of patrons is not only the largest cluster of venue patrons (53%), but also the patron group most likely to engage in the riskiest behavioral classes. Taken together, these results suggest the riskiest type of alcohol venues selectively attract the clientele who exhibit the greatest risk behavior associated with elevated risk of HIV infection.

By contrast, establishments favored by non-mixed clusters of locals or foreign tourists were safer sex venues. These safer sex venues were deemed “lower risk” because they are more likely to have condoms available for purchase than venues characterized by elevated levels of sex work. Safer venues were also most likely to be characterized by heavy drinking, suggesting that safer venues tend to be “watering holes” favored by patrons who drink rather than those seeking drug transactions or sexual encounters.

Our analyses also revealed that foreign tourists’ attendance at alcohol venues in Sosúa falls into two distinct activity paths: (1) attending “risky” venues favored by all groups of patrons, or (2) attending lower risk “safer” or “equipped” venues favored by foreign tourists alone. Importantly, the behavior of foreign tourists varied by which patron cluster they associated with. Tourists belonging to the mixed class of patrons were more likely to engage in a higher frequency and greater variety of HIV risk behaviors including heavy drinking, heterosexual and/or same sex transactions, and drug transactions. Foreign tourists alone were most likely to engage in heavy drinking followed by sex transactions. When foreign tourists alone sought sexual encounters, they were more likely to do so in the context of equipped venues which have greater availability of HIV preventative services. In contrast, foreign tourists in the mixed class seeking sexual encounters were likely to do so in a risky venue with lower availability of HIV prevention services. Taken together, the stratification of individual drinkers into different patron clusters has important consequences as each cluster adopts a distinct behavioral typology and preferred type of drinking establishment with differing associated levels of HIV risk.

Although several theories have evolved to explain the emergence of problem behavior in alcohol venue settings, our findings are consistent with a “micro-macro dynamic” reflecting interaction between venue setting and patron behavior (Gruenewald et al., 2007). For example, gravity models posit that certain venues attract specific patrons who may be more disposed to a riskier behavioral profile (Gruenewald, 2007). The behaviors of these individuals may aggregate to form normative group behavior and subsequently influences the behaviors of individuals themselves. Our findings are consistent with this social dynamic in that the mixed cluster of patrons are more likely to adopt all HIV risk behaviors compared to when they are isolated as tourists or locals. At the same time, the high concentration of alcohol venues in Sosúa revealed by GIS mapping likely fuels the segmentation of venues, as establishments diversify their features and available services to compete for a greater share of potential patrons. Thus, the simultaneous processes of venue stratification and aggregate patron behavior may stimulate the diversification of patrons and venue establishments into cluster subgroups of varying HIV vulnerability (Gruenewald, 2007). The overlap of these clusters generates high-risk locations where the behaviors of patrons interact with the social structures of venues to aggravate HIV risk.

The identification of high risk alcohol venues has implications for HIV prevention in that data can be used to target resources to priority areas. Prevention resources might initially focus on venues where there is the greatest opportunity for preventing new infections (Measure Evaluation, 2005). Our results demonstrate the need for direct involvement of local policymakers, community agencies, and venue managers to increase HIV prevention resources in identified “risky” venues where population mixing and sexual exchanges occur. HIV preventative resources in this setting can prevent infection among people seeking sexual encounters, and thus most at-risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV. Of interest is identifying prevention services and policies that owners and staff of such high- risk venues are amenable to adopting, or, alternatively, mandating such services and policies through local legislation. Consistent with recommendations from previous HIV prevention efforts in the D.R. (Kerrigan et al., 2003; Padilla et al., 2012), research on garnering and coordinating the support of local community agencies will be critical to the long-term sustainability of multi-level HIV prevention interventions.

Important to note are the limitations of this study. Collected data relied heavily on key informant responses creating potential for bias, although survey data was supplemented with direct observation, where appropriate. Additionally, as the focus of the current study was on venue-level characteristics, data were not collected on individual risk behavior or on health outcomes, which should be explored in future research. Despite limitations, we believe our study presents important findings related to venue characteristics and HIV risk.

4.1. Conclusions

In sum, our findings elucidate mechanisms by which alcohol venues may facilitate HIV risk by characterizing three attributes of the alcohol venue environment: structural features, types of patrons, and venue-level behaviors. While research has tended to focus on individual risk behavior within venues, we identify the need for prevention efforts to address how contextual and structural factors of alcohol venues affect HIV vulnerability. In order to better inform prevention measures, future research should recognize the clustering of high-risk normative group behaviors in these settings and investigate how other HIV risk behaviors, such as drug use, are influenced by alcohol venue structure. Future research should also document the types of macro-level interventions that will be most effective in reducing HIV risk and the extent to which those interventions are feasible to implement within alcohol venues. The typologies identified in the present paper are a starting point for doing so.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source: This work was supported by NIAAA Grant 1R21AA018078. The NIAAA had no further role in study design; in the collection analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

The authors would like to thank Bernardo Gonzalez and Roberto Martinez for their assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:...

Supplementary material can be found by accessing the online version of this paper at http://dx.doi.org and by entering doi:...

Contributors:

Authors Vincent Guilamo-Ramos and Mark Padilla designed the study and wrote the protocol. Authors Viktor Lushin and James Jaccard undertook the statistical analysis. Author Katharine McCarthy managed the literature searches, summaries of previous work and contributed to data interpretation. Authors Katharine McCarthy, Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, and James Jaccard wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Author Leah Meisterlin contributed to the geographic analysis and figure development. Authors Molly Skinner-Day and Zahira Quiñones assisted with final manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: No conflicts declared.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agresti A, Caffo B. Simple and effective confidence intervals for proportions and differences of proportions result from adding two successes and two failures. Am Stat. 2000;54:280–288. [Google Scholar]

- Ao TT, Sam N, Kiwelu I, Mahal A, Subramanian SV, Wyshack G, Kapiga S. Risk factors of alcohol problem drinking among female bar/hotel workers in Moshi, Tanzania: a multi-level analysis. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:330–339. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9849-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan D. What’s Love Got To Do With It? Transnational Desires and Sex Tourism in the Dominican Republic. Duke University Press; Durham, NC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant KJ. Expanding research on the role of alcohol consumption and related risks in the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41:1465–1507. doi: 10.1080/10826080600846250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caribbean Tourism Organization. [acessed March, 2012];Latest Tourism Statistics: Dominican Republic. 2011 http://www.onecaribbean.org/statistics/2011statistics/default.aspx.

- Centro de Estudios Sociales y Demográficos (CESDEM) [República Dominicana] Informe Preliminar Sobre VIH/SIDA. Santo Domingo, República Dominicana: CESDEM; 2002. República Dominicana: Encuesta demográfica y de salud (ENDESA 2002) [Google Scholar]

- Cook RL, Clark DB. Is there an association between alcohol consumption and sexually transmitted diseases? A systematic review Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:156–164. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000151418.03899.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: evaluating the evidence. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002;14:101–117. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiStefano C, Kamphaus RW. Investigating subtypes of child development: a comparison of cluster analysis and latent class cluster analysis in typology creation. Educ Psychol Measur. 2006;66:778–794. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz KE, Morojele N, Kalichman SC. Alcohol: the forgotten drug in HIV/AIDS. Lancet. 2010;7:398–400. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60884-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz KE, Woelk GB, Bassett MT, McFarland WC, Routh JA, Tobaiwa O, Stall RD. The association between alcohol use, sexual risk behavior, and HIV infection among men attending beerhalls in Harare, Zimbabwe. AIDS Behav. 2002;6:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- George WH, Stoner SA. Understanding acute alcohol effects on sexual behavior. Ann Rev Sex Res. 2000;11:92–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go VF, Solomon S, Srikrishnan AK, Sivaram S, Johnson SC, Sripaipan T, Murugavel KG, Latkin C, Mayer K, Celentano DD. HIV rates and risk behaviors are low in the general population of males in South India, but high in alcohol venues: results from 2 probability surveys. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;46:491–497. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181594c75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ. The spatial ecology of alcohol problems: niche theory and assortative drinking. Addiction. 2007;102:870–878. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Samet JH. Alcohol and HIV disease progression: weighing the evidence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7:226–233. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0060-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Woolf-King SE, Muyindike W. Adding fuel to the fire: alcohol’s effect on the HIV epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8:172–180. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Zack MM. A latent class modeling approach to evaluate behavioral risk factors and health-related quality of life. Prev Chron Dis. 2011;8:A137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC. Social and structure HIV prevention in alcohol-serving establishments. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33:184–194. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Cain D. The relationship between indicators of sexual compulsivity and high risk sexual practices among men and women receiving services from a sexually transmitted infection clinic. J Sex Res. 2004;41:235–241. doi: 10.1080/00224490409552231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Cain D, Jooste S, Peltzer K. HIV/AIDS risk reduction counseling for alcohol using sexually transmitted infections in clinic patients in Cape Town, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:594–600. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180415e07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Cain D, Jooste S, Peltzer K. Randomized trial of a community-based alcohol-related HIV risk-reduction intervention for men and women in Cape Town South Africa. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:270–279. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Vermaak R, Jooste S, Cain D. HIV/AIDS risks among men and women who drink at informal alcohol serving establishments (Shebeens) in Cape Town, South Africa. Prev Sci. 2008;9:55–62. doi: 10.1007/s11121-008-0085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan D, Ellen JM, Moreno L, Rosario S, Katz J, Celentano DD, Sweat M. Environmental-structural factors significantly associated with consistent condom use among female sex workers in the Dominican Republic. AIDS. 2003;17:415–423. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200302140-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J, Garnett G, Mhlanga S, Nyamukapa C, Donnelly C, Gregson S. Beer halls as a focus for HIV prevention activities in rural Zimbabwe. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:364–369. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000154506.84492.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mataure P, McFarland W, Fritz K, Kim A, Woelk G, Ray S, Rutherford G. Alcohol use and high-risk sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults in Harare, Zimbabwe. AIDS Behav. 2002;6:211–219. [Google Scholar]

- MEASURE Evaluation. Priorities for Local AIDS Control Efforts (PLACE): A Manual for Implementing the PLACE Method. U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID); Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Morojele NK, Kachieng’a MA, Mokoko E, Nkoko MA, Parry CD, Nkowane AM, Moshia KM, Saxena S. Alcohol use and sexual behaviour among risky drinkers and bar and shebeen patrons in Gauteng province, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary A, Holtgrave D, Wright-Deaguero L, Malow RM. Innovations in approaches to preventing HIV/AIDS: applications to other health promotion activities. In: Valdiserri R, editor. Dawning Answers: How the HIV/AIDS Epidemic has Helped to Strengthen Public Health. Oxford University Press; Oxford, England: 2003. pp. 76–95. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver-Felez D, Finlinson HA, Deren S, Robles RR. Mapping the air-bridge locations: the application of ethnographic mapping techniques to a study of HIV risk behavior determinant in East Harlem, New York and Bayamon, Puerto Rico. Hum Organ. 2002;61:262–276. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla MB. Caribbean Pleasure Industry: Tourism Sexuality and AIDS in the Dominican Republic. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla MB, Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Reyes AM. HIV/AIDS and tourism in the Caribbean: an ecological systems perspective. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:70–77. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.161968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla MB, Guilamo-Ramos V, Godbole R. A syndemic analysis of alcohol use and sexual risk behavior among tourism employees in Sosua, Dominican Republic. Qual Health Res. 2012;21:89–102. doi: 10.1177/1049732311419865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandrea I, Happel KI, Amedee AM, Bagby GJ, Nelson S. Alcohol’s role in HIV transmission and disease progression. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33:203–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivaram S, Srikrishnan AK, Latkin C, Iriondo-Perez J, Go VF, Solomon S, Celentano DD. Male alcohol use and unprotected sex with non-regular partners: evidence from wine shops in Chennai, India. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia: its prized and dangerous effects. Am Psychol. 1990;45:921–933. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Geneva: 2010. UNAIDS Report on Global AIDS Epidemic. [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS. Dominican Republic. Geneva: 2011. UNAIDS HIV/AIDS Fact Sheet. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations World Tourism Organization. [accessed on May 22, 2010];International tourism to reach one billion in 2012. 2012 http://media.unwto.org/en/press-release/2012-01-16/international-tourism-reach-one-billion-2012.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.