Abstract

Summary

With the introduction of the next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, remarkable new diagnostic applications have been established in daily routine. Implementation of NGS is challenging in clinical diagnostics, but definite advantages and new diagnostic possibilities make the switch to the technology inevitable. In addition to the higher sequencing capacity, clonal sequencing of single molecules, multiplexing of samples, higher diagnostic sensitivity, workflow miniaturization, and cost benefits are some of the valuable features of the technology. After the recent advances, NGS emerged as a proven alternative for classical Sanger sequencing in the typing of human leukocyte antigens (HLA). By virtue of the clonal amplification of single DNA molecules ambiguous typing results can be avoided. Simultaneously, a higher sample throughput can be achieved by tagging of DNA molecules with multiplex identifiers and pooling of PCR products before sequencing. In our experience, up to 380 samples can be typed for HLA-A, -B, and -DRB1 in high-resolution during every sequencing run. In molecular oncology, NGS shows a markedly increased sensitivity in comparison to the conventional Sanger sequencing and is developing to the standard diagnostic tool in detection of somatic mutations in cancer cells with great impact on personalized treatment of patients.

KeyWords: NGS, HLA, Molecular oncology

Introduction

Massively parallel sequencing technologies, commonly subsumed under the term next generation sequencing (NGS) dramatically changed the possibilities of basic research and clinical diagnostics in comparison to the conventional Sanger sequencing. After the introduction of the technology about 10 years ago, with improvements in accuracy, robustness, and handling NGS became a widely used alternative to the Sanger sequencing [1]. Most valuable advantages of the technology are i) the increased number of sequenced bases per run, ii] parallel sequencing of different target regions, and iii) clonai sequencing of single DNA molecules. Implementation of the NGS technology contributed to the exponential increase of genomic information. High capacity to produce sequencing information can be utilized in many indications, such as whole genome, exome, epigenome, cancer genome, or microbiome analysis [2, 3, 4, 5]. Technological progress has already led to the discovery of genes in causal relationship with inherited diseases and helps in elucidation of molecular pathways of complex diseases [6, 7]. On the other hand, targeted resequencing of tens or hundreds of selected genes is useful in medical diagnostics of genetic disorders. In the majority of diseases where the genetic background is determined not merely one gene but rather a number of genes, conceivably interacting with one another can lead to the overlapping or indistinguishable disease phenotypes. For example, in cardiac arrhythmias, car-diomyopathies, connective tissue disorders, or mental retardation, tens of genes may be involved, and sequencing of hundreds of exons is needed [8]. These gene candidates can be analyzed in parallel in one working procedure, instead of a step-by-step approach used in Sanger sequencing, allowing a significant reduction of the analytical turn-around time. At the end, a final diagnosis is made earlier, with possibly therapeutic consequences for the patients.

In respect of clonai sequencing of single molecules, there are advantages in typing of highly polymorphic genes (e.g. HLA) or in molecular oncology [9]. Due to the already high but still increasing number of known HLA alleles, conventional Sanger sequencing does not allow unambiguous HLA typing in the majority of cases anymore. A time- and work-consuming allele-specific amplification approach is needed to resolve ambiguities, which can only be offset by lower throughput or by increasing manpower. With clonai amplification of single DNA molecules and read lengths of more than 400 bp, most of the cis-trans ambiguities can be resolved by NGS technology [10]. In molecular oncology, many new somatic tumor mutations, associated with disease progression or response to specific targeted therapies, have been found in the last years. NGS technology enables the parallel analysis of mutations in a number of genes in one workflow. In addition, mutations in mixed biopsies can be detected with higher sensitivity in comparison to Sanger sequencing [11]. Furthermore, different tumor sub-clones can frequently be detected in biopsies, as new mutations may occur during the course of the disease. Subclones can easily be differentiated by NGS, which not only allows a more precise interpretation of sequencing data but may also have an impact on the therapeutic decisions [12].

Errors in NGS data may arise from incorrect genome mapping, failures in base calling, or contamination with extrinsic DNA [13]. As sequencing errors tend to accumulate towards the read end, longer reads are in general better than shorter ones and can be trimmed near the end. In regard to the sequence alignment, longer reads are again of advantage since incorrect mapping results from the sequence similarities in repetitive regions or with pseudogenes. In individual reads NGS shows a higher error rate than Sanger sequencing, and data generated by using the Roche 454 or Ion Torrent PGM platform seems to have a higher raw error rate than sequences from Illumina [14]. Nevertheless, error rates are significantly reduced by increasing the depth of sequencing coverage, and with sufficient coverage SNP calling is closely matched between all technologies. In a routine diagnostic setting, a minimum coverage should be defined for definite determination of the underlying genotype. Sequenced regions are not uniformly covered. Coverage declines with high AT- or GC-rich background and significant exon- or sample-specific differences in coverage can be observed [15]. Consequently, an average coverage must be about 2–3 times higher to fulfill the minimum requirements in coverage over the complete sequenced region. Unfortunately, consensus guidelines for minimum acceptable coverage are not yet defined.

Besides diagnostic and clinical benefits, from economical point of view sequencing costs per base and per sample can be reduced by NGS technology. However, the cost benefit can entirely be exploited only if the capacity of the sequencing instrument is fully utilized. In terms of costs, Sanger sequencing is the method of choice if the sequence information from only few exons of just few samples is needed. In NGS, with parallel analysis of different target regions and by multiplexing of samples, standardized workflows can be established, lowering the need of manual handling and enhancing the sample throughput. Automation of individual steps allows the additional reduction of hands-on time. In parallel, more time must be invested into the bioinformatic data processing and interpretation of detected genetic variants [16].

NGS Technologies in Clinical Diagnostics

Currently, most suitable and most proven NGS technologies for routine diagnostic applications are: i) Roche 454 platforms (GS FLX and GS Junior) (Roche Life Sciences, Branford, CT, USA), ii) Life Technologies IonTorrent PGM (Life Technologies, Guilford, CT, USA) and iii) Illumina's HiSeq and MiSeq systems (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) [3, 17]. Each instrument is capable of generating huge amounts of sequencing data - many times higher in comparison to Sanger sequencing. However, depending on the underlying sequencing method, throughput and instrument-specific errors and caveats vary greatly between the systems. In case of relatively low number of targeted exons, genes or regions, e.g. in HLA typing or in molecular oncology, all instruments could be considered for sequencing. Parallel sequencing of tens or hundreds of genes or whole exome/genome requires the use of instruments with higher capacity, e.g. the HiSeq platform. Important criteria when comparing different methods for sequencing include throughput of the system, cost per megabase of sequence, accuracy of results, and multiplexing capabilities. In the following, the technological aspects and differences between the platforms are briefly discussed and summarized (table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of sequencing instruments performance metrics for amplicon sequencing (table adapted from Glenn, 2011 [3])

| Instrument | Amplification | Run time, h | Reads 106 | Read length | Yield, Mb | Cost/Mb, USD | Multiplexing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 454 Junior | emPCR | 8 | 0.1 | 450–550 | 35–50 | ∼50 | 151MIDs |

| 454 GS FLX | emPCR | 10 | 1 | 450–550 | 350–700 | ∼12 | 151MIDS 1–16 regions |

| IonTorrent | emPCR | 2–4+ | ∼0.1–4* | 200–300 | 10–1,000* | ∼100–0.75* | 96 |

| MiSeq | bridgePCR | 27–40+ | ∼5–15§ |

|

1,500–5,000§ | ∼0.75–0.25§ | 96 |

| 96 | |||||||

| 3730×1 (capillary) | PCR | 2 | 0.000096 | 650 | 0.06 | 1500 | no |

Depending on employed sequencing chip (314, 316, or 318).

depending on read length.

depending on read length and cluster density.

Even though sequencing prizes are dropping rapidly, the costs for whole genome sequencing are still prohibitive for most applications. Therefore, enrichment of target regions, i.e., a specific set of genes or exons, should be performed. Especially in clinical diagnostics, only disease-relevant genes are sequenced. There are mainly two distinct enrichment methods available: selection of target regions by PCR amplification and enrichment of target regions by complementary oligonucleotide hybridization.

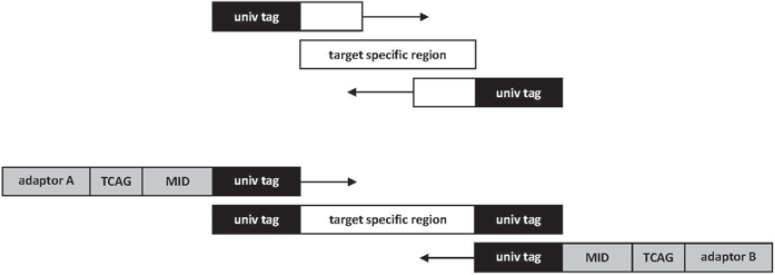

The first approach uses amplicon-specific primers with universal tag sequences to amplify target regions by PCR. The PCR contains a second primer pair with a patient-specific DNA barcode or multiplex identifier tag (MID) and the sequencing adaptors.

Highly multiplexed, amplicon-based systems for target enrichment are commercially available by a number of providers, for example Illumina TruSeq Custom Amplicon (TSCA), Agilent HaloPlex (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA), or Ion AmpliSeq™ (Life Technologies).

The basic principle of target enrichment by oligonucleotide hybridization is as follows: DNA or RNA oligonucleotides of specific length (55–120 bp) are designed complementary to the target regions. These baits are then hybridized to the fragmented genomic DNA and bind to their respective target sequences. Fragments bound by the baits are then enriched by magnetic beads. The enriched fragments are subsequently amplified by PCR and further processed to a finished sequencing library. Several different enrichment systems are available, e.g., Agilent SureSelect, Illumina TrueSeq Custom Enrichment (TSCE), and Roche NimbleGen. All protocols follow in general the outlined steps but differ in length, spacing, and molecule type (DNA or RNA) of the baits [18].

Roche, 454 GS FLX and GS Junior

In 2005, Roche Life Sciences was the first company that commercialized a NGS platform [1]. Roche 454 sequencing platforms employ emulsion PCR (emPCR) for clonai sample amplification followed by massively parallel pyrosequencing. The throughput amounts to 350–700 Mb per 10-hour run on the GS FLX and 30–50 Mb per 8-hour run on the GS Junior, the benchtop version of the sequencing system. The mean read length is between 450 and 550 bp, enabling the sequencing of moderate to large amplicons. With an upgrade to a GS FLX+ system, read lengths of up to 1,000 bp can be reached, increasing the sequencing throughput and enabling a more accurate sequence assembly. Unfortunately, up to now, the upgrade is not available for amplicon sequencing.

During the emPCR, the template DNA is bound to specific beads and clonally amplified. Afterwards, DNA carrying beads are enriched and deposited into reaction wells containing all necessary sequencing enzymes on a 454 PicoTiterPlate™ (PTP). The plate is subsequently flowed with one of the four dNTPs, resulting in the incorporation of complementary nucleotides in the DNA template strand. After each nucleotide flow a luminescence signal of the incorporated nucleotide(s) is emitted and recorded by an integrated CCD camera.

Multiplexing capabilities are two-fold for the 454 platforms. Firstly, 151 multiplex identifiers (MIDs) are available in the extended Roche MID set. MIDs are specific, short oligonucleotide sequences that are ligated to the template DNA and serve as unique identifier for all sequences obtained from a single patient. During analysis the MID sequence is recognized and all sequences originating from the same patient can be grouped together. Secondly, the sequencing slide may be partitioned into 2, 4, 8, or 16 distinct compartments, allowing for an even greater scale of multiplexing. As an example, in the routine HLA typing, we are using up to 4 plate regions with up to 95 samples in each, i.e., analysis of 380 samples in one GS FLX run is feasible with the current sequencing capacity of the platform.

The main drawbacks of the technology are systematic errors in homopolymer regions and the relatively high costs per base of the sequencing. The flow-based sequencing approach results in incorporation of multiple identical nucleotides in a single flow in case of a homopolymer stretch in the template. The emitted signal is in theory proportional to the number of incorporated nucleotides. However, in practice signal strength does not increase linear with growing homopolymer length, resulting in exceeding difficulty to call the correct number of bases with increasing homopolymer length [2,17].

Illumina, MiSeq

The Illumina sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) technology, first introduced by the group of Solexa in 2006 [19], was the second NGS method to be commercialized. Fragmented template DNA is immobilized on the surface of a transparent glass slide termed flow cell, where the sequencing is facilitated. Clusters of identical DNA molecules are formed by a PCR-like process called bridge amplification. The sequencing is performed cycle-wise employing reversible terminator chemistry, thus ensuring the incorporation of a single, fluorescent-labeled nucleotide during each individual sequencing cycle. After cleavage of the fluorescent dye and the optical detection of the signal, the terminator group is removed, enabling further strand elongation in the following cycle.

A distinctive feature of the Illumina SBS chemistry is the natural capacity to perform paired-end sequencing runs. This denotes that two distinct sequencing reads are performed, one from each end of the template DNA fragments. These may be separated by a stretch of unsequenced DNA of distinct length termed insert. Insert size distributions can provide valuable information to infer structural variations or in de novo genome sequencing. Alternatively, the paired-end reads may overlap to join the two distinct reads together in order to form a longer, continuous read. This joined read can then for example be employed in amplicon sequencing to generate reads that encompass the complete amplicon length.

Several studies have been conducted to investigate the technology-specific error rate of the SBS approach, showing that substitution errors are more prevalent than insertion/deletion errors. Due to decaying signal intensity errors accumulate in later cycles at the read ends [17, 20, 21].

There are several sequencing instruments employing this approach, namely the Genome Analyzer (GA) IIx and the HiSeq series instruments (HiSeqlOOO, HiSeq2000, HiSeq2500). One of the newest developments is the MiSeq benchtop sequencing instrument. In contrast to the former instruments the MiSeq profits from novel chemistry, enabling much faster run times. Currently, the system is capable of performing 2 χ 150 bp and 2 × 250 bp runs in about 27 and 40 h run time, respectively. In total, a throughput of 1.5–5 Gb is possible, making the system the most suitable (in Illumina's sequencing portfolio) for amplicon sequencing. In terms of multiplexing capabilities the MiSeq uses a dual-index strategy where 12 different forward MIDs may be combined with 8 distinct reverse MIDs for a total of 96 distinguishable samples per run. With regard to the throughput of the platform, additional, custom-designed MIDs are needed to harness the complete capacity of the system for amplicon sequencing.

lonTorrent, PGM

In February 2010 Ion Torrent Inc. released a novel sequencing technology based on ion semiconductors that is now commercialized by Life Technologies [22]. This technique is also referred to as pH-mediated sequencing, silicon sequencing, or post-light sequencing. It follows a traditional sequencing-by-synthesis approach as a DNA template strand is complementarized, although the method of detecting the incorporated nucleotides differs substantially from other sequencing instruments. The incorporation of a dNTP into a growing DNA strand involves the formation of a covalent bond and the release of pyrophosphate and a positively charged hydrogen ion. The Ion Torrent system detects hydrogen ions as they are released during nucleotide incorporation by the DNA polymerase by a shift in the pH level. Microwells on a semiconductor chip containing the template DNA strand to be sequenced and a DNA polymerase are subsequently flooded with a single type of nucleotide at a time. If the nucleotide is complementary to the template it is incorporated and releases a hydrogen ion. In the case of a homopolymer stretch in the template, multiple, identical nucleotides can be incorporated in a single flow. Beneath the layer of microwells is an ion-sensitive layer with a sensor that detects the emitted signal.

One of the main strengths of the system is the sequencing speed. The measurements can almost be performed in real time (4 s per incorporation), resulting in a run time of approximately 2–4 h, which is significantly lower than the run time of comparable systems. In contrast to other sequencing instruments, no optic devices are needed and unmodified nucleotides can be employed. This circumvents potential biases that can arise from the use of artificially altered dNTPs [22]. There are three different sequencing chips available with an increasing number of sequencing wells to enable different scales of throughput: the 314 chip enables an output of up to 10 Mb, the 316 chip up to 100 Mb, and the 318 chip up to 1 Gb. The chips cannot be further partitioned, yet there are 96 MIDs available for multiplexed sequencing. The chemistry is rapidly updated, and currently kits for mean read length of 200 bp and 300 bp are available.

Due to the flow-based sequencing setup the lonTorrent PGM suffers from similar problems in accurately determining the length of homopolymer stretches as the Roche 454 sequencing systems. If multiple identical nucleotides are incorporated in one flow the signal strength does not increase linear, resulting in difficulties to discern the exact length of a homopolymer stretch in the template.

HLA Typing by NGS

HLA typing in the clinical routine diagnostics encompasses HLA matching of donor and recipient in the transplantation setting, relative risk assessment in regard to HLA-associated autoimmune diseases or adverse drug reactions as well as chimerism monitoring/analysis. Furthermore, HLA typing is applied in context of HLA-specific peptide vaccination treatment for cancer as well as to study population genetics, evolutionary pathways of the HLA variation, regulatory mechanisms of HLA expression, and disease associations.

Three DNA-based methods are conventionally used for HLA typing - SSP (sequence-specific primers), SSOP (sequence-specific oligonucleotide probes) and Sanger sequencing (sequence-based typing; SBT), the latter of which has been considered the most comprehensive method so far [23]. These applications are primarily focused on sequence analysis of the antigen recognition site (ARS) of the HLA molecule, the most polymorphic site in the HLA genes and that with highest clinical relevance. According to the HLA typing standards [24], only exons 2 and 3 of HLA class I genes and exon 2 of HLA class II genes must be assessed, and other parts of the HLA genes are usually not typed due to time and cost constraints. However, the clinical relevance of other exons remains unknown. Moreover, many non-expressed HLA alleles contain polymorphisms outside the ARS, and identification of these null alleles is critical in the setting of blood stem cell transplantation as confusion with a normally expressed variant would result in an antigen mismatch between donor and recipient. To date (January 2013) more than 8,400 HLA alleles are listed in the IMGT/HLA database [25], but less than 10% are completely sequenced [26]. Since the number of identified alleles still increases, the string of ambiguous alleles, differing outside the ARS, is growing.

The second major source of ambiguities inherent to SBT is the difficulty to set phase of polymorphisms in a heterozygous sample, resulting in two or more different allele combinations that produce identical consensus sequences. Resolving these ambiguities requires haplotype separation, which is costly and labor-intensive.

Two crucial properties of all available NGS technologies facilitate the resolution of this type of ambiguities. First, clonai sequencing of single DNA molecules allows to set the phase of linked polymorphisms, resolving cis-trans ambiguities. Second, all platforms produce a very large amount of sequenced bases (number of sequencing reads), giving the possibility to analyze larger parts or even complete genomic sequences of several HLA genes in hundreds (GS FLX, Roche) or even thousands (HiSeq, Illumina) of samples in parallel. For example, patients may benefit from additional matching for HLA-DP, -DRB3/4/5 or -G genes, or genes with immunomodulatory function could be sequenced [27, 28]. For HLA typing three NGS technologies are currently used: Roche 454, Illumina SBS systems, and Ion Torrent PGM (Life Technologies). Initially, the preferred system for HLA typing was the Roche 454 GS FLX and the bench-top version GS Junior due to the advantage of long reads. Roche 454 started with read lengths of 250 bp and now improved to 400–500 bp with the titanium chemistry. The recently launched GS FLX+ system allows to produce even longer reads with up to 1,000 bp. When NGS first ‚intruded‘ into the field of immunogenetics, the Illumina system was no real option, generating only short reads with 100–150 bp. With improving the read length to 2 χ 250 bp (paired end) since middle of 2012, the MiSeq platform becomes an alternative to the Roche 454 technology.

PCR amplification is the most suitable method for target enrichment in highly polymorphic regions like HLA genes. Usually, amplification and sequencing of only few clinically relevant exons is performed. To cover complete exons with a maximum length of 276 bp, the method must be able to produce reads with at least 300–350 bp, and primers must be located close to the exons, which might be challenging. Alternatively, large parts of the HLA genes or even the complete genomic sequence of the genes is amplified in long-range PCRs followed by fragmentation of the PCR product, ligation of MID-tagged adaptors, and shotgun sequencing of the generated fragments.

Amplicon-based enrichment offers an advantage that DNA library is created without the need for subsequent manipulation such as fragmentation. Bentley et al. [29] used so-called 454 HLA fusion primers for amplification of 14 exons of HLA-A, -B, -C (exons 2, 3, 4), HLA-DRB1, -DPB1, -DQA1 (exon 2), and HLA-DQB1 (exons 2, 3). These primers consist of three components. Additionally to the target specific sequence they contain adaptor sequences for binding the amplicons by DNA capture beads and MID sequences to uniquely label and identify an individual sample. With MID tags amplicons from many different samples can be prepared, pooled, and sequenced in one region of a single sequencing run. A set of 12 different MIDs allows to sequence 24 or 48 samples in every GS FLX sequencing run by using 2 or 4 physically separated PTP regions. Overall average sequence coverage ranged from 500 to 700 reads with a length of around 250 bp. For HLA genotype assignment Conexio ATF software (Conexio Genomics, Fremantle, Australia) was used, which compares the sequence reads with known HLA allele sequences from the IMGT/HLA database. Concordance of 454 GS FLX-determined HLA genotypes with reference genotypes was 99.4% for 7 loci. In about 20% of the genotype assignments, manual editing was necessary for correct calling. The editing required exclusion of rare sequences that had not been filtered out by the software, trimming of sequences with sequencing errors at the end of the reads, and exclusion of rare sequence reads that had been assigned as second allele in homozygous samples. Subsequent versions of the software addressed these issues, and the need of manual editing is significantly reduced to 3.7% in a recent study [30]. Sequence reads from related HLA genomic sequences that might be co-amplified along with the target sequence are automatically filtered out by the software, preventing ‘background’ signals as it would occur in SBT or SSOP. This and further studies have shown that the ampli-con sequencing strategy on the Roche 454 system is feasible for routine HLA typing, allows the resolution of cis-trans ambiguities, and facilitates a reliable determination of HLA genotypes at allelic level [15, 30, 31].

In 2011, a double-blind multi-site study was conducted to evaluate robustness and reliability of the HLA sequencing procedure described by Bentley et al. [30]. Eight laboratory sites with varying levels of experience in sequencing on the 454 GS FLX platform received the same set of previously typed DNA samples to perform amplicon sequencing (14 exons) using GS FLX standard chemistry with the same reagents and protocols. The samples were genotyped for HLA-A, -B, -C, -DPB1, -DQA1, -DQB1, -DRB1 and -DRB3/4/5, and sequence alignment was achieved by the Conexio ATF software. Two pools of ten samples each were loaded on a PTP. Although some of the participants had little to no experience with the NGS platform and the Conexio ATF software, the overall concordance of genotyping assignments was very high (97.2%). Notably, three of the samples contained novel alleles, which were detected by all participants. However, correct assignment of genotypes correlated with the experience of the laboratory in manual editing of sequence data. Manual workflow for 20 samples, consisting of PCR, amplicon cleanup, quantification, quality check, dilution, and pooling followed by emPCR, sequencing, and data analysis was time-consuming and required 5 working days.

All previous studies have shown that multiplexing of several samples is possible although only few samples were sequenced in parallel to achieve very high coverage (up to several hundreds) of sequence reads per amplicon and sample. Gabriel et al. [31] sequenced exons 2, 3,4, of HLA-A and -B from 8 donor samples in one GS FLX run, resulting in an average coverage of 5,000 reads per amplicon for one sample. A significant number (44%) of the initial reads yet did not pass the internal quality control filters of the GS FLX analysis software, mainly due to short read lengths and mixed reads, as a result of the amplification of more than one specific DNA molecule on one bead in the emPCR.

Another study reported similar failure rates (24–55%) of unusable reads [32]. The number of possible samples that could be multiplexed depends on the capacity of the platform to produce quality reads, read length, number of amplicons, and available MIDs as well as on the desired coverage. Improvement of sequencing and library preparation chemistry and protocols could increase the percentage of quality reads and therefore the efficiency of the system in the future. As experience increases, a universally valid minimum coverage for allele calling should be assessed, keeping in mind that, even if preferential amplification of certain alleles occurs, allele dropout in assignment must be avoided. It has been reported that 8χ coverage identifies 99.99% of SNPs [33] and Wang et al. [34] stated that a minimal coverage of 20 reads should provide reliable results for HLA typing.

With sequencing of more exons, introns, and regulatory elements of the HLA genes or even of the complete genomic region, higher resolution results in the exact assignment of HLA alleles without any ambiguities. For this purpose, the long-range PCR approach has been employed so far. As shown by Lind et al. [32], full-length sequences of the class I genes HLA-A, -B, and -C and the continuum of a genomic region containing exons 2 and 3 of the class II genes HLA-DRB1, and -DQB1 were amplified in long-range PCRs. Advantageous is the possibility to place primers in less polymorphic regions allowing for improved resolution of genetic differences and using only one set of primers per locus. Exons of the same gene can be amplified in one fragment, decreasing variation in coverage.

PCR products were fragmented to 400–800 bp by nebulization with nitrogen gas and fragments were enzymatically polished to generate blunt ends for ligation of MID-tagged adaptors. GS FLX standard chemistry was used for preparation of 4 samples, which were shotgun-sequenced each on 1/8 of a PTP. Sequence data were assembled and analyzed using the Conexio ATF software. The average read depth was 698, and for most loci the ratio between both alleles was close to 1. An average of 95.5% of quality reads were aligned and resulted in correct HLA typing. The study shows that NGS sequencing of the entire HLA genes (in case of class I) is possible and provides unambiguous characterization of HLA alleles, eliminating all geno-typing ambiguities that would remain by amplification of single exons as described before. However, amplified gene parts included regions that are typically not sequenced, and alignment of these regions is challenging due to the lack or incomplete reference sequences. In a subsequent study, the group provided full genomic sequences for 15 previously only partially sequenced common and well-documented HLA class I alleles using long-range PCR amplification [26].

A similar approach was recently adopted to the Illumina NGS platforms by Mindrinos group [34]. They sequenced 40 cell lines for HLA-A, -B, -C (genomic sequence of exons 1–7), and -DRB1 (genomic sequence of exons 2–5) on the Illumina GAIIx sequencing platform to evaluate their workflow. Library preparation included genomic long-range PCR, fragmentation by sonification to 300–350 bp and ligation of MID-tagged adaptors. An emPCR step as required for other NGS systems is not necessary. Each fragment was sequenced in 150 bp length from both ends (paired-end read sequencing run). The method was additionally tested on the Illumina HiSeq and MiSeq platforms typing 59 and 5 clinical samples, respectively. Furthermore, they developed a unique genotyping algorithm to include sequences of genomic regions lacking references in the IMGT/HLA database for genotype assignment. They reached an overall concordance rate of 99% with previous results and could discover three new alleles, illustrating high fidelity of the method and the ability to identify previously undescribed alleles. With the recent introduction of a new chemistry, the MiSeq system is capable to produce 2 χ 250 bp paired-end reads, making the direct amplicon sequencing approach of complete exons feasible on Illumina's platform.

The strategy of performing long-range PCR and shotgun sequencing of the fragmented PCR products was expanded to comprise the entire sequence from the enhancer-promoter region to the 3UTR of 8 HLA genes (HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, -DQB1, -DPB1, -DPA1, -DQA1) [35]. In this study, ten samples were analyzed on the Roche Junior system using titanium chemistry and 4 samples on the Ion Torrent PGM system. In case of the Ion Torrent PGM system, raw data processing and output of quality filter reads were performed by the Torrent Suite 1.5.1 (Life Technologies) and mapping to reference sequences in the IMGT/HLA database by the GS Reference Mapper Ver. 2.5 (Life Technologies). If a reference sequence was not available, a new virtual reference sequence was constructed by de novo assembly using the Sequencher Ver. 4.10 DNA sequence assembly software (Gene Code Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Using the Ion Torrent PGM system, the workflow was manageable in 4 days, and by combining the Ion Torrent 318 chip with 32 barcodes for 200 bp reads and a minimum coverage of 30, the calculated costs were USD 17 per locus and sample. In all samples HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1 allele sequences were determined at the 8-digit level. 21 HLA allele sequences were newly determined, among them 17 new alleles (most of them with SNPs or indels in introns) and 4 extensions of partial HLA sequences to full-length sequences. HLA-DQA1, -DPA1, and -DPB1 alleles could not be assigned at the 8-digit level because the polymorphism densities to separate both phases were much lower than in the other HLA loci. Phasing problems could be solved by application of 3rd generation sequencers such as the single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencer PacBio RS (Pacific Biosciences, Menlo Park, CA, USA) with read lengths exceeding 2 kb. Lind et al. [36] already sequenced full-length HLA class I genes with a consensus sequence accuracy of 99.9% using the PacBio RS sequencer, showing the applicability of SMRT sequencing for HLA genotyping. Yet, the method still shows the highest error rates (15%) compared to other NGS chemistries which can be overcome only by sufficient high coverage.

Recent studies demonstrate that full-length HLA sequencing enables an HLA typing without ambiguities and allows distinct characterization of new and existing HLA alleles as well as null alleles. Full-length HLA sequencing would complete the HLA sequence database, containing only about 10% complete allele sequences so far, and a final nomenclature system for HLA alleles could be created. Primer/probe design as well as genotype assignment would be substantially facilitated. The potential clinical impact of HLA mismatches outside the antigen recognition site could be investigated more thoroughly. However, several factors must be considered before implementation of this approach into the routine workflow. The preparation of the DNA library requires additional steps compared to the direct amplicon sequencing. Since larger gene parts are analyzed, higher sequencing capacity is consumed per sample leading to increased costs. So far, analysis of sequence regions without or only partial reference sequences in the IMGT/HLA database requires suitable software and good bioinformatic knowledge of how to perform de novo assembly of sequence reads. Software for HLA genotype assignment has to handle different NGS data output formats and has to be improved concerning the new or different requirements for the assessment of NGS sequence data compared to data generated by Sanger sequencing. The benefit of the additional information in different contexts has to be balanced with these issues.

High-Throughput HLA Typing

The NGS technology holds many benefits that facilitate its application in HLA typing in dependence of established objectives and evidently improves genotyping results. However, it is burdened by high costs for the initial investments and high reagent costs for single runs. Hence, processing of single or few samples is not affordable, and a sufficient number of samples is needed to operate on a cost-covering basis. A further disadvantage is the time-consuming workflow. In comparison to Sanger sequencing, where results can be delivered in 2–3 days, at least 4–5 days are needed from sample entrance to the final report by using an NGS platform. In view of the long workflow, reliability of the technology gains even more importance in routine clinical usage. The number of samples and long processing time may become a limitation for introduction of the NGS technology in an HLA typing unit, in particular if HLA typing is performed only for related or unrelated blood stem cell donor search.

Considering all HLA-specific advantages and disadvantages of the NGS technology and in regard to our center-specific demands, we decided to develop an NGS workflow for initial HLA typing of voluntary blood stem cell donors. In this setting, a high number of samples is continuously available, and results must not be delivered in a tight timeframe. In addition, typing requirements are the same for all of the samples. To increase the sample throughput, we focused on the sequencing of only mandatory HLA genes and exons, except for exon 3 of HLA-DRB1 and -DQB1 genes. With regard to the sequencing platform, 2 years ago, when we started to work with NGS, only Roche 454 technology was able to produce sequences with acceptable read length. Due to the extremely high variability of HLA genes and exons with a length of up to 276 bp, read lengths of at least 300 bp are needed for a reliable sequence alignment. Recently, also the paired-end sequencing strategy of Illumina allows a production of sequences with read length of up to 500 bp.

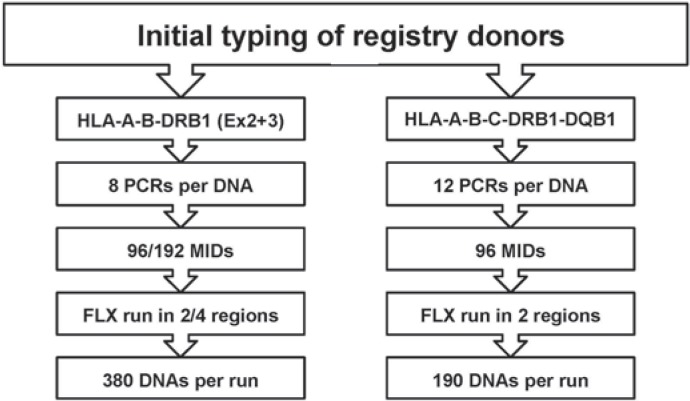

The aim of the project was the HLA-A, -B and -DRB1 typing of at least 380 DNA samples in one sequencing run on the GS FLX sequencer. To handle hundreds of samples and thousands of PCR products in every run, an automated high-throughput workflow was established on three Microlab STARlet (Hamilton Robotics, Reno, NV, USA) workstations.

HLA typing is performed for exon 2 and 3 of HLA-A, -B, and -DRB1 loci. Sequencing of HLA-DRB1 exon 3 is not mandatory but beneficial in detection of possible allele dropouts since exon 2 and 3 are amplified with two different primer sets. DNA library construction and sequencing with the 454 GS FLX Sequencing System using titanium chemistry is performed as described by Bentley et al. [29]. Briefly, a dsDNA amplicon library is prepared by PCR with 8 target-specific primer pairs located in the respective intron regions to amplify the complete exon sequences. In addition, a second primer pair containing unique MID tags and adaptor sequences for bead capture is added to each reaction (fig. 1). By using MID tags, PCR products can be pooled together after the first amplification. As MID tags are sequenced in the same read with the target sequence (HLA al-lele), HLA alleles can be referred back to the DNA samples. For multiplexing 96 samples, the fusion primer approach is not convenient since for every single amplicon as many primer pairs as used MID tags are required.

Fig. 1.

Target specific primer pairs (upper part] containing an universal tag sequence at the 5 end are combined with MID-primer pairs (lower part), which consist of the universal tag at the 3’ end, an MID sequence for identification of individual samples and a 4 bp-key sequence (TCAG), required for signal calibration. At the 5’ end, Roche 454 specific adaptor sequences A / B are included, which are necessary for binding of PCRamplicons to the DNA capture beads for emPCR.

In every PCR run, 5 HLA exons of 95 donor samples and 1 negative control are amplified in 8 PCRs per donor sample, resulting in the generation of two 384-well PCR plates. Ampli-cons are then pooled together, resulting in 8 χ 1.5 ml tubes, each containing the same target region from 95 donor samples and one negative control. Agencourt AMPure XP™ (Beckman-Coulter, Krefeld, Germany) beads are used to purify the ampli-cons. Hereafter, amplicon pools are quantified by PicoGreen (Life Technologies) and diluted to the appropriate concentration of 1 Mio molecules/μl for the following clonai amplification in emulsion on capture beads. Eight pools are then mixed together and prepared for emPCR. The emPCR is performed in a 96-well PCR plate, resulting in clonai amplification of one DNA fragment on a single bead. After emulsion breaking and recovery of the beads, DNA-carrying beads are enriched using the Roche 454 REM e System to yield between 5 and 20% enrichment of the beads. Finally, sequencing primers are annealed to the emPCR amplicons on the beads to prepare sequencing-ready samples. In each well of the PTP - containing 1.6 × 106 wells in total - only one bead can be deposited, carrying millions of copies of one specific DNA molecule. Many sequence reads can be obtained in parallel, and sequence data from a single well corresponds to a single DNA molecule. Using 96 MIDs, up to 96 samples can be sequenced per PTP region. Thus, four PCR runs with 95 donor samples and 1 negative control each are prepared for one sequencing run. Accordingly 380 DNA samples are HLA-A-, -B-, and -DRBl-typed in one run. Alternatively, 192 MIDs can be used instead of 96, and beads are loaded on a PTP using a 2-region gasket. At the end, sequences are assigned with SeqHLA 454 software (JSI medical systems, Kippenheim, Germany). In general, the accuracy of single reads is inferior by using NGS technology in comparison to Sanger sequencing. Drawbacks in accuracy of single reads are offset by comparing redundant sequences that cover the same genomic region multiple times. Hence, sequencing depth (coverage) provides accuracy, and the higher coverage leads to the lower error rates. So far, standards for minimum coverage as well as for NGS in general are not defined by the HLA community. In our setting, HLA typing results are accepted if both alleles are sequenced at least 10 times without any errors (20 times in homozygous loci). To achieve a minimum coverage of 10, we calculate with a mean coverage of at least 50.

The second workflow was developed to type for HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1. 12 PCR are needed per DNA sample to amplify exon 2 and 3 of each gene. Again, 96 to 192 MIDs are used and sequencing is performed in one or two PTP regions. Up to 192 samples can be typed for HLA-A, -B, -C, -DRB1, and -DQB1 in one sequencing run (fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Two routine workflows for high-resolution, high-throughput HLA typing by NGS.

The liquid handling steps for library preparation, pooling, PCR purification and emPCR enrichment are automated on Microlab STARlet instruments. In the pre-PCR area, one workstation is used for PCR setup. In the post-PCR area, one workstation is used for pooling of PCR products and for fully automated emPCR enrichment and sequence primer annealing steps. The second post-PCR workstation is used for automated PCR purification by Agencourt AMPure XP™ beads.

The proportion of ambiguities was assessed in a cohort of 475 donors, initially typed by NGS for HLA-A, -B, and -DRB1. HLA-DRB1 was sequenced in exon 2 only at that time. In HLA-A locus, unambiguous assignment of both alleles was never possible, but all results can be reported with suffix G, denoting alleles with identical nucleotide sequences across the exons encoding the peptide binding domains (exon 2 and 3). No cis-trans ambiguities inside of exon 2 and 3 occurred. In HLA-B locus, two out of 475 samples were unambiguous (0.4%), 467 samples can be reported with suffix G (98.3%), and 6 cis-trans ambiguities inside of exon 2 and 3 were found (1.3%). In the HLA-DRB1 locus, 77 typing results were unambiguous (16.2%); the remaining results can be reported with suffix G. Since only one exon of HLA-DRB1 is amplified, no cis-trans ambiguities were expected and not observed in fact (table 2).

Table 2.

Evaluation of ambiguities in a cohort of 475 volunteer blood stem cell donors HLA typed by NGS on Roche 454 GS FLX platform

| Locus | Unambiguous (%) | Results with ‘G’ (%) | Ambiguous (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HLA-A | 0 (0.0%) | 475 (100%) | 0 (0%) |

| HLA-B | 2 (0.4%) | 467 (98.3%) | 6 (1.3%) |

| HLA-DRB1 | 77 (16.2%) | 398 (83.8%) | 0 (0%) |

In our experience, HLA typing by the NGS technology is feasible in routine usage. A high to ultra-high resolution can be achieved, depending on the number of exons sequenced. By high number of samples, HLA typing can be performed for costs at least comparable with Sanger sequencing. High costs for automation and initial investments must be considered.

Molecular Oncology

Biomarkers become more and more important in the diagnostic and therapy of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. Diagnostic biomarkers allow the differential diagnosis of a disease within a group of closely related disorders, prognostic biomarkers give conclusions regarding the prognosis or progression of a disease, and predictive biomarkers indicate the likelihood of developing a disease in the future or to predict response to targeted therapies and facilitate the selection of the best individual treatment. In times of personalized medicine, mutational status of molecules that regulate critical growth and survival pathways in cancer cells should be part of the pretreatment workflow [37, 38]. For example, in colorectal cancer, patients with a mutation in the KRAS (exon 2 and 3) or BRAF (exon 15) gene will not respond to a treatment with the monoclonal antibodies cetuximab (Erbitux®) or panitumumab (Vectibix®), whereas in non-small cell lung cancer patients especially with mutations in the EGFR gene (exon 18,19, 20, 21) will benefit from a treatment with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib (Tarceva®) or gefitinib (Iressa®) [39, 40]. However, also mutations responsible for resistance to the therapy are described. Table 3 shows therapy-relevant biomarkers in a set of solid tumors.

Table 3.

Therapy-relevant biomarkers ir a set of solid tumors

| Tumor entity | Genes | Exon | Allel | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal carcinoma | KRAS | 2, 3 | wild type | cetuximab (Erbitux®); |

| BRAF | 15 | wild type | panitumumab (Vectibix®) | |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | EGFR | 18, 19, 20, 21 | mutated* | erlotinib (Tarceva®); gefitinib (Iressa®) |

| KRAS | 2, 3 | wild type | ||

| BRAF | 15 | wild type | ||

| KRAS | 2, 3 | mutated | selumetinib** | |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | C-KIT | 9, 11, 13, 17 | mutated* | imatinib (Glivec®); |

| PDGFRa | 12,14,18 | mutated* | sunitinib (Sutent®) | |

| Malignant melanoma | BRAF | 15 | mutated* | vemurafenib (Zelboraf®) |

Also mutations leading to resistance.

Phase 2 study [39].

Traditional approaches of sequence analysis like Sanger sequencing and pyrosequencing are widely used to guide for patients diagnosed with lung and colorectal cancer as well as for patients with melanoma, sarcomas (e.g., gastrointestinal stromal tumors), and subtypes of leukemia and lymphoma [41]. These sequence approaches, especially Sanger sequencing, have some relevant limitations compared to targeted resequencing by NGS. Whereas Sanger sequencing has a sensitivity of about 15% (mutated sequences in wild-type background), NGS has a much higher sensitivity achieved by sequencing depth. A recommended minimum coverage of 1,000 results in a sensitivity of about 3–5%. This enables the detection of minorities in a high background of wild-type sequences as well as the detection of tumor subclones. Especially in tumor tissue with a high fraction of normal tissue, mutations can be over-seen by Sanger sequencing. Low mutation burdens must always be set in relation to the heterogeneity of the material and whether a microdissection was possible. However, the clinical impact of the lower mutation burden detected by NGS must be clarified in further studies. In addition, mutations with low frequency have to be validated to exclude sequencing errors or DNA modifications which can be generated by desamination in formaldehyde-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue [42]. With NGS, all relevant regions can be analyzed in a single approach which allows the use of small biopsies for the analysis. In non-small cell lung cancer, a limited sample size is a frequent problem in daily routine. Furthermore, an allele discrimination is possible with NGS technology if two or more mutations can be expected on the same amplicon. If the mutations are on different alleles, there are two possibilities: first, the tumor is compound heterozygous for the two mutations; second, the tumor shows intra-tumor heterogeneity. Another advantage of NGS is the possibility of massive parallel sequencing of many samples in a time-saving and cost-efficient manner.

In our center, solid tumor tissue samples are macrodissected by a pathologist, and DNA is isolated using QIAamp FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). NGS is applied for mutational screening in the relevant exons, depending on the tumor type. Target-specific primers for these exons are designed using Primer3 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/). Amplicons are designed with a length of about 250 bp. After the first amplification with target-specific primers, the second PCR is performed with sequencing adaptors (A and B) for Roche 454 sequencing and individual MID tags. The quality of the amplicons is examined on a 2% agarose gel. Thereafter, amplicons can be pooled, and the library is purified using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen) followed by purification with Agencourt AMPure XP beads. Purification efficacy is monitored with a DNA 1000 chip on the Bioanalyzer (Agilent) and libraries are quantified using the Quant-iT PicoGreen Kit. NGS is performed using the 454 titanium amplicon chemistry. According to the manufacturer's recommendations, the multiplexed amplicon pools are first diluted to 106 molecules/1. This working dilution is used as starting concentration for the GS Junior emPCR Kit (Lib-A). Following the emPCR amplification, clonally amplified beads are enriched for Roche 454 sequencing according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Enrichment is quantified on a CASY Cell Counter (Roche Applied Sciences, Mannheim, Germany). The Roche 454 sequencing data are generated on a GS Junior instrument using the GS Junior Titanium Sequencing Kit. The expected coverage for each amplicon is 1,000 reads. Data analysis is performed utilizing JSI Sequence Pilot, SEQNext software (JSI medical systems). This workflow can also be used for mutational analysis of hematologic malignancies. Samples from solid tumors (FFPE material) and hematologic malignancies (blood or bone marrow) can be processed in the same sequencing run.

In comparison to Sanger sequencing, the NGS technology offers many unique features such as higher sequencing capacity, clonai sequencing of single molecules, multiplexing of samples, higher diagnostic sensitivity, workflow miniaturization, and reduction of sequencing costs per base. Advantages of the technology can be utilized in numerous diagnostic applications. With recent improvements, NGS developed into the method of choice to perform a real high-resolution HLA typing combined with high throughput of samples. A full-length sequencing of HLA genes or even of the whole major histocompatibility complex may become feasible in the search of most suitable blood stem cell donors or in other clinical applications such as diagnostics of autoimmune diseases or in pharmacogenomics.

In molecular oncology, predictive biomarkers have led to personalized treatment in solid tumors and hematological malignancies. This treatment is based on the mutational status of certain genes in the cancer cells. High sensitivity of the NGS technology enables the detection of mutations in heterogeneous samples or detection of tumor subclones. With highly parallel testing of multiple parameters and samples in a single NGS run, processing of small biopsies is feasible in a daily routine. In the future, these techniques may be applicable to analyze fine-needle aspirates or effusions and circulating tumor cells.

References

- 1.Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, Attiya S, Bader JS, Bemben LA, et al. Genome sequencing in micro-fabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wheeler DA, Srinivasan M, Egholm M, Shen Y, Chen L, McGuire A, et al. The complete genome of an individual by massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nature. 2008;452:872–876. doi: 10.1038/nature06884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glenn TC. Field guide to next-generation DNA sequencers. Mol Ecol Res. 2011;11:759–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2011.03024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyerson M, Gabriel S, Getz G. Advances in understanding cancer genomes through second-generation sequencing. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:685–696. doi: 10.1038/nrg2841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuczynski J, Lauber CL, Walters WA, Parfrey LW, Clemente JC, Gevers D, et al. Experimental and analytical tools for studying the human microbiome. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:47–58. doi: 10.1038/nrg3129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coonrod EM, Durtschi JD, Margraf RL, Voelkerding KV. Developing Genome and exome sequencing for candidate gene identification in inherited disorders. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012;DOI: 10.5858/arpa.2012–0107-RA. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kotschote S, Wagner C, Marschall C, Mayer K, Hirv K, Kerick M, et al. Translation of next-generati on sequencing (NGS) into molecular diagnostics (in German) Laboratoriumsmedizin. 2010;34:311–318. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin X, Tang W, Ahmad S, Lu J, Colby CC, Zhu J, et al. Applications of targeted gene capture and next-generation sequencing technologies in studies of human deafness and other genetic disabilities. Hear Res. 2012;288:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman M, Warren EH, 3rd, Wu CJ. Applications of next-generation sequencing to blood and marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2012;18(suppl):S151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gabriel C, Stabentheiner S, Danzer M, Proli J. What next? The next transit from biology to diagnostics: next generation sequencing for immunogenetics. Transfus Med Hemother. 2011;38:308–317. doi: 10.1159/000332433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandao GDA, Brega EF, Spatz A. The role of molecular pathology in non-small-cell lung carcinoma -now and in the future. Curr Oncol. 2012;19(suppl 1):S24–32. doi: 10.3747/co.19.1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kohlmann A, Grossmann V, Haferlach T. Integration of next-generation sequencing into clinical practice: are we there yet? Semin Oncol. 2012;39:26–36. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vogl I, Eck S, Benet-Pagès A, Greif P, Hirv K, Kot-schote S, et al. Diagnostic applications of next generation sequencing: working towards quality standards (in German) Laboratoriumsmedizin. 2012;36:227–239. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quail MA, Smith M, Coupland P, Otto TD, Harris SR, Connor TR, et al. A tale of three next generation sequencing platforms: comparison of Ion Torrent, Pacific Biosciences and Illumina MiSeq sequencers. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:341. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erlich RL, Jia X, Anderson S, Banks E, Gao X, Car-rington M, et al. Next-generation sequencing for HLA typing of class I loci. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nekrutenko A, Taylor J. Next-generation sequencing data interpretation: enhancing reproducibility and accessibility. Nat Rev Genet. 2012;13:667–672. doi: 10.1038/nrg3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loman NJ, Misra RV, Dallman TJ, Constantinidou C, Gharbia SE, Wain J, et al. Performance comparison of benchtop high-throughput sequencing platforms. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30:434–439. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clark MJ, Chen R, Lam HYK, Karczewski KJ, Chen R, Euskirchen G, et al. Performance comparison of exome DNA sequencing technologies. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:908–914. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow HP, Smith GP, Milton J, Brown CG, et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature. 2008;456:53–59. doi: 10.1038/nature07517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura K, Oshima T, Morimoto T, Ikeda S, Yoshikawa H, Shiwa Y, et al. Sequence-specific error profile of Illumina sequencers. Nucl Acids Res 2011; DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkr344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Minoche AE, Dohm JC, Himmelbauer H. Evaluation of genomic high-throughput sequencing data generated on Illumina HiSeq and genome analyzer systems. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R112. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-11-r112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothberg JM, Hinz W, Rearick TM, Schultz J, Mileski W, Davey M, et al. An integrated semiconductor device enabling non-optical genome sequencing. Nature. 2011;475:348–352. doi: 10.1038/nature10242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erlich H. HLA DNA typing: past, present, and future. Tissue Antigens. 2012;80:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2012.01881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.European Federation of Immunogenetics Standards for Histocompatibility and Immunogenetics Testing, version 6.0. www.efiweb.eu/index.php?id=102 (last accessed January 8, 2013).

- 25.Robinson J, Halliwell JA, McWilliam H, Lopez R, Parham P, Marsh SGE. The IMGT/HLA database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1222–D1227. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lind C, Ferriola D, Mackiewicz K, Sasson A, Monos D. Filling the gaps - the generation of full genomic sequences for 15 common and well-documented HLA class I alleles using next-generation sequencing technology. Hum Immunol 2012; DOI: 10.1016/j. humimm.2012.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Fleischhauer K, Shaw BE, Gooley T, Malkki M, Bardy P, Bignon J-D, et al. Effect of T-cell-epitope matching at HLA-DPB1 in recipients of unrelated-donor haemopoietic-cell transplantation: a retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:366–374. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70004-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiusolo P, Bellesi S, Piccirillo N, Giammarco S, Marietti S, De Ritis D, et al. The role of HLA - G 14-bp polymorphism in allo-HSCT after short-term course MTX for GvHD prophylaxis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2012;47:120–124. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2011.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bentley G, Higuchi R, Hoglund B, Goodridge D, Sayer D, Trachtenberg EA, et al. High-resolution, high-throughput HLA genotyping by next-generation sequencing. Tissue Antigens. 2009;74:393–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2009.01345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holcomb CL, Hoglund B, Anderson MW, Blake LA, Böhme I, Egholm M, et al. A multi-site study using high-resolution HLA genotyping by next generation sequencing. Tissue Antigens. 2011;77:206–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2010.01606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gabriel C, Danzer M, Hackl C, Kopal G, Hufnagl P, Hofer K, et al. Rapid high-throughput human leukocyte antigen typing by massively parallel pyrosequencing for high-resolution allele identification. Hum Immunol. 2009;70:960–964. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lind C, Ferriola D, Mackiewicz K, Heron S, Rogers M, Slavich L, et al. Next-generation sequencing: the solution for high-resolution, unambiguous human leukocyte antigen typing. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:1033–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2010.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hedges DI, Hedges D, Burges D, Powell E, Almonte C, Huang J, et al. Exome sequencing of a multigenerational human pedigree. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang C, Krishnakumar S, Wilhelmy J, Babrzadeh F, Stepanyan L, Su LF, et al. High-throughput, high-fidelity HLA genotyping with deep sequencing. Proc Nati Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:8676–8681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206614109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shiina T, Suzuki S, Ozaki Y, Taira H, Kikkawa E, Shigenari A, et al. Super high resolution for single molecule-sequence-based typing of classical HLA loci at the 8-digit level using next generation sequencers. Tissue Antigens. 2012;80:305–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2012.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lind C, Mackiewicz K, Duke J, Sasson A, Ranade S, Sethuraman A, et al. Single molecule real-time sequencing of full length HLA class I genes - the promise and current reality. 137-P. Hum Immunol. 2012;73:135. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allegra CJ, Jessup JM, Somerfield MR, Hamilton SR, Hammond EH, Hayes DF, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: testing for KRAS gene mutations in patients with meta-staüc colorectal carcinoma to predict response to anti-epidermal growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2091–2096. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.21.9170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monzon FA, Ogino S, Hammond MEH, Hailing KC, Bloom KJ, Nikiforova MN. The role of KRAS mutation testing in the management of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1600–1606. doi: 10.5858/133.10.1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen K-SH, Neal JW. First-line treatment of EGFR-mutant non-small-cell lung cancer: the role of erlo-tinib and other tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Biologies. 2012;6:337–344. doi: 10.2147/BTT.S26558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jänne PA, Shaw AT, Pereira JR, Jeannin G, Vans-teenkiste J, Barrios C, et al. Selumetinib plus do-cetaxel for KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. The Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:38–47. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cronin M, Ross JS. Comprehensive next-generation cancer genome sequencing in the era of targeted therapy and personalized oncology. Biomark Med. 2011;5:293–305. doi: 10.2217/bmm.11.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Do H, Dobrovic A. Dramatic reduction of sequence artefacts from DNA isolated from formalin-fixed cancer biopsies by treatment with uracil- DNA glycosylase. Oncotarget. 2012;3:546–558. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]